Joshua Corey's Blog, page 16

August 1, 2016

Hannah and the Master

A work in progress that has maybe hit a wall and is maybe finished. The image above shows its seven sections over my desk at the Vermont Studio Center, where I'm supposed to be doing something entirely different (finishing a novel).

What is Hannah? A philosophical screenplay? A science-fiction poem? A hallucinatory biography of Hannah Arendt as representative political thinker of the 20th and 21st centuries? Yes, yes, and yes. Martin Heidegger is the Master. Paul Celan, Simone Weil, and George Oppen guest star.

A chunk of the first major section, Clockwise / The Wave can be read at The Offending Adam: http://theoffendingadam.com/2015/10/05/from-hannah-and-the-master/

A smaller piece appeared in a recent issue of SRPR: http://www.srpr.org/files/40.2/from_Hannah_and_the_master.pdf

Looking for interested readers.

May 28, 2016

Elegy, Arcadia, Apostrophe

Elegy and Arcadia: the two poles of my imagination, united by the poetic trope of apostrophe: the address to someone or something not there.

The void in the vocative O!

Arcadia is the past, the lost paradise whose imaginary function is inseparable from its pastness, its lostness. But Arcadia, ironized, can also be of the future. And when I think of the future, I think of elegy: seeking after consolation for what has been irretrievably lost.

Francis Ponge, whose collection of prose poems Le parti pris des choses will be published in September in a new translation by myself and Jean-Luc Garneau, accomplished an Arcadia of the present in a series of near-apostrophes to common everyday objects. The oyster, the orange, the cigarette, they may very well have been, probably were, there. But were they, are they, capable of reciprocating the poet's attention, his address? Here's our version of "L'huître":

OYSTER

The oyster, though the size of an average pebble, has a more rugged appearance, with less uniformity to its brilliant whitishness. It is a world obstinately closed. All the same it can be opened: grip it with a rag, use a serrated knife that’s not too sharp, and work at it doggedly. Curious fingers will cut themselves and break their nails; it’s dirty work. The blows administered to the shell sheath it in white circles, sort of like halos.

Inside one finds an entire world to be eaten and drunk, underneath a firmament (to speak precisely) of mother-of-pearl. The heavens above collapse into the heavens below, forming a pond, a viscous little green bag, ebbing and flowing in our smell and sight, fringed with a blackish lace.

On very rare occasions a little phrase pearls in its nacreous throat, which we immediately seize for a decoration.

The oyster is not so much addressed as described, and yet that description contains a kind of deification, a spiritualization achieved paradoxically through Ponge's dry, pseudo-scientific attention to such physical details as the ruggedness of the shell's exterior and the pearliness of its interior. The oyster takes on a spiritual life as it becomes unstable in the poet's eye, shifting unpredictably from object to metaphor and back again. All of Ponge's things are constantly changing into language and back again, and our attitude toward them, as toward language, can be affected by our humanism or merely rapacious, as when we "seize for a decoration" the "little phrase [that] pearls in its nacreous throat."

Ponge's original for "phrase" is "une formule"; my translation as "the little phrase" alludes to the little phrase of Vinteuil's sonata in Swann's Way by Proust, a snatch of music that becomes, for Swann, the metonymic emblem of his passion for Odette. As Proust writes, the phrase changes as Swann listens to it; at first he appreciates "only the material quality of the sounds which those instruments secreted"; then the notes of the phrase "substituted (for his mind's convenience) for the mysterious entity" he began to perceive after hearing it repeatedly; finally it is played, again and again, inexpertly, by the fingers of Odette for Swann's pleasure; it becomes symbolic and debased, just as Odette herself is the debased and inadquate vessel for the finest and strongest emotions that Swann will ever be capable of feeling. She is there; he even marries her; but the marriage itself is a kind of apostrophe or elegy to the dead feelings the real Odette has come to represent.

Everything I write seems to take this form--of course writing itself represents what is not there, presents nothing other than itself. It's been fascinating to write fiction, to tell stories, because it throws into sharper relief language's poetic function. When I write a poem, the language is primary; when I write a story, representation of an imaginary world takes precedence, though the most vivid representations, or images, are those that pull some participatory impulse out of the reader to make them real. Poetry, by comparison, is weirdly self-sufficient, or so it can seem. The reader's encounter with it doesn't complete the poem; if anything, poems are repellent, experiences on the page that fling the reader back out into the moment. They are the absolute opposite of stories, or social media posts; they don't absorb the reader but confront him in vivid strangeness, like Ponge's oyster.

Most readers are impervious to the poem's all-but-mute appeal; it requires a certain perversity (pun intended) to have a taste for language being itself. The rest must be lured by the sop of story, the bones of meaning, as in T.S. Eliot's famous analogy: "The chief use of the 'meaning' of a poem, in the ordinary sense, may be (for here again I am speaking of some kinds of poetry and not all) to satisfy one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the poem does its work upon him: much as the imaginary burglar is always provided with a nice piece of meat for the house-dog."

The words, the apostrophe, are really there: on the page, in your ear. The lost person, or yet-to-be place, cannot be. These are the rules of the game, but they are played differently in poetry, in translation, and in fiction. I am learning these rules. In the new novel that I have just finished, an artificial Arcadia is the scene of elegy: the survivor of a disaster, living in relative comfort, mourns the woman who did not, chose not, to survive with him. He apostrophizes her, addresses her, throughout: she is the muse of the story that he tells of his survival and his community. But unlike Beautiful Soul, Concord is not a poem. It is, I hope, a bit more canny about the poetic difference, even as it exists within the continuum that has so long defined what I write.

February 4, 2016

Mary

His sister's name was Mary and his wife's name was Mary and his mother's name had also been Mary, and in the long slow days of his decline he often blamed on this trifecta of Marys the feelings of manifest humiliation that had dogged him from the first moment he'd looked across the table at the woman he'd made his bride and saw not love, nor even contempt, but only a shade of Maryness paler and more washed out than the face of the dark Mary that had given birth to him or the Mary mouldering in the grave, Morphine Mary, who from her hospital bed had told him to fuck off and from whom until that moment with his wife he thought he had forever turned his face.

"The odd thing is that we're Jewish, and Mary's not a Jewish name," he said to her.

"Not lately, anyway," she answered.

October 19, 2015

Return to HOWL

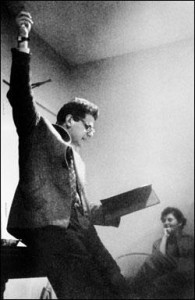

Allen Ginsberg reads at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, October 7, 1955.

Every time I think I'm out, they pull me back in. Last year it was William S. Burroughs' hundredth birthday celebrated by a European Beat Studies Network conference in Tangier. This year it's the sixtieth anniversary of Allen Ginsberg's first reading of Howl in San Francisco. I'll be in Brussels for the ESBN conference commemorating that event, performing a Ginsberg-themed piece as part of The Muttering Sickness. I don't even like the Beats, I keep telling myself. I'm not an angst-ridden teenager any more. I'm old enough to see through their genius for self-promotion, the easy recuperation by the culture of their attack on the forces of patriarchy, conformity, and capitalism. (Spontaneous Bop Capitalism, we ought to call it.) Kerouac wore khakis, Burroughs was a lowlife, Ginsberg wrote three or four indelible poems and was otherwise a bearded self-referential embarrassment. What keeps me coming back?

It's personal. When I posted that photo on Facebook, someone commented that it looked a lot like me. And while I don't have the genes to become bald or grow a beard, that simple fact--that as a young poet I could find so easily an image for myself reflected in the world--meant something.

Just look at the guy. You can see the charisma, but in spite of the black and white and the cigarette or roach he's smoking, there' s nothing cool about those glasses, the intensity of the gaze, the shockingly sensuous mouth. If Ginsberg embarrasses he embarrasses by his warmth and vulnerability and nervous joy in living. His words and image made it possible for my younger self to imagine that my inability to be cool, to live indifferent and defended, might not mean my automatic and inevitable destruction.

Or rather, that it might be possible to live with the knowledge of destruction. For Ginsberg is one of the most-death haunted poets I know. It's all over Howl and of course it's the reason for being of Kaddish, an unbearably personal poem, not least for me because my own mother, although far from mad, exhibited qualities of depression and narcissism that marked me for life, and then of course she died young, as it happens less than a mile from the "The mental hospital--state Greystone," one of the several grim palaces where Naomi Ginsberg was treated for her mental illness. (It's also where Woody Guthrie spent his last years losing the battle with Huntington's; Bob Dylan famously visited him there.)

When Ginsberg addresses Carl Solomon in Howl, when he says, "I'm with you in Rockland," he's really talking to his mother. She is the muse he cannot deny, who terrifies and threatens him, the possessor, in Allen Grossman's formulation, of "an insane idealism of which her son is heir" (Long Schoolroom 154), and for whom he musters a truly astonishing compassion. In one of the most uncanny passages of Kaddish he embraces, almost literally, the stench of mortality and sadness that has come to surround her flesh, as it surrounds all flesh, though we pretend not to smell it:

One time I thought she was trying to make me come lay her—flirting to herself at sink—lay back on huge bed that filled most of the room, dress up round her hips, big slash of hair, scars of operations, pancreas, belly wounds, abortions, appendix, stitching of incisions pulling down in the fat like hideous thick zippers—ragged long lips between her legs—What, even, smell of asshole? I was cold—later revolted a little, not much—seemed perhaps a good idea to try—know the Monster of the Beginning Womb—Perhaps—that way. Would she care? She needs a lover.

Yisborach, v’yistabach, v’yispoar, v’yisroman, v’yisnaseh, v’yishador, v’yishalleh, v’yishallol, sh’meh d’kudsho, b’rich hu.

Birthdeath, "the Monster of the Beginning Womb," revolted only "a little, not much," followed by the Hebrew that only comparatively late in life am I beginning to get a feel for, if not comprehension of: Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He. Something I say, or ought to say, every December 21, on the anniversary of my own mother's death.

As with Ginsberg, my mother represents a portal to the incomprehensible cruelty of the past. In Naomi's case, she is haunted, sometimes comically, by the specter of Adolf Hitler--"she saw his mustache in the sink." My own mother was herself a Holocaust survivor, born in Budapest in 1942, hidden with her grandparents in the ghetto while her own parents, my grandparents, Ernest and Eva Montag, were sent to Auschwitz. Miraculously, both survived, and returned to Hungary to collect their little girl, and spent a few years in the British DP camp in Bergen Belsen before emigrating to this country, where she grew up in the long shadow of her parents' trauma, in Queens.

Fifty years ago, in the summer of '65, incessant traveler Ginsberg managed to get himself kicked out of two socialist countries in succession (Cuba and Czechoslovakia), as he writes in a long and entertaining letter to the legendary antipoet Nicanor Parra. He also, in passing and by the way, paid a visit to Auschwitz, a visit summed up in one peculiar sentence in his letter to Parra: "Then a week in Krakow which hath a beauteous cathedral with giant polychrome altarpiece by medieval woodcarver genius Wit Stoltz, and car ride to Auschwitz with some boy scout leaders who were trying to pick up schoolboys hanging around the barbed wire gazing at tourists." This borders on bad taste: is the perpetually horny Ginsberg unable to notice anything at the camp other than the vaguely predatory behavior of the "boy scout leaders" he is inexplicably traveling with? And who the hell was Wit Stoltz? Google turns up only Ginsberg's letters and, if you don't use quotation marks, footage of Eric Stoltz as Marty McFly in unused footage from Back to the Future.

On Sunday, October 25, sixty years after Howl and fifty-six years after Kaddish and fifty years after Ginsberg made nothing, at least nothing obvious, of standing on the ashen ground of Auschwitz, and eighteen years after Ginsberg's death in New York, I will visit Auschwitz-Birkenau for the first time. Although Ginsberg had already written the poems on which his reputation stands by the time of his own visit, there is a case to be made that those poems are saturated by the experience of the Shoah, as processed through the ambiguous relation of an American Jewish poet to that experience. Allen Grossman puts it this way:

The characteristic literary posture of the postwar poet in America is that of the survivor—a man who is not quite certain that he is not in fact dead…. ’Since so many like me died, and since my survival is an unaccountable accident, how can I be certain that I did not myself die and that America is not in fact Hell, as indeed all of the social critics say it is?’ Ginsberg’s poetry is the poetry of a terminal cultural situation. It is a Jewish poetry because the Jew is a symbolic representative of man overthrown by history. (153)

Grossman goes on to claim that "Ginsberg's chief artistic contribution in Kaddish is a virtually psychotic candor that affects the mind less like poetry than like some real experience that is so terrible that it cannot be understood. In America, which did not experience the Second World War on its own soil, the Jew indeed may be the proper interpreter of horror" (157). That "virtually" is interesting because what we have here are paired and opposed virtualities: the virtuality of "the bitter logic of the poetic principle" (poetry's effacement or erasure of the actual in its pursuit of representation) versus "virtually psychotic candor," a break not with representation but with reality itself. Kaddish, in other words, comes as close as any (American) poet can to presenting something like the unrepresentable horror of the war, something which can otherwise only be given in the testimony of survivors, the only discourse unbarred by the Adornian dictum "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

Implicitly or maybe explicitly, Grossman criticizes Ginsberg and other American poets for reducing the disasters of the twentieth century to the personal. But what other ground does a fundamentally lyric poetry (and I believe that Ginsberg is a lyric poet, in spite of the length of his most famous poems) have to work from? Put another way, I feel myself as a poet and writer forever trying to reconstitute the conditions that ground my imagination and its powers, however limited. I've dedicated at least one novel to trying to reimagine, from a skewed perspective, the mental life of my mother; in another novel I'm imagining the moment my parents met; in yet another project I use the Heidegger-Arendt affair as a kind of ground zero moment of the twentieth century but project it into the twenty-first, so as to make the resources we've developed around the problem of the unimaginable (in history) available for imagining the future.

For me there's no getting away from Allen Ginsberg; poetically speaking he's my gay grandfather, mon hypocrite semblable, whose drolly encompassing prosody seems to promise, as Grossman suggests, not a description of experience but experience itself. A kind of wit matched with the darkest recesses of experience, intended not to aggrandize the self but which makes the lyric I into the imperiled traveler (a drunken boat) we all are.

Standing on that bare ground, in Poland, my head bathed by the smokeless air, I will encounter neither Allen nor my grandparents nor the angel of history but sheer contingency, fragility, the monster of beginning, that which enables fate.

October 4, 2015

A book to come

In the very near future, when the virtual blogs and the discussion boards will have collapsed, a book will be printed in the tradition of 17th century layered epistles, as if it were part of a “manuscript culture where names were highly unstable texts and where alternative, often discrete modes of authorship and text presentation thrived” to reveal the relation between the person, literature and the social. (Marci North). It will be called:

The Letters of Carla, the letter b.

A Mystery in Poetry

with a foreword by

The Future Guardian of the Letters

and an

Afterword by Benjamin Hollander

(and it will be described, thusly):

Before others got involved, The Letters of Carla, the letter b.: A Mystery in Poetry was the modest attempt of one disciple to speak about and save her hero, Heriberto Yépez , from the controversies surrounding his critique of the poetic empire shaped by the North American poet, Charles Olson.

However, Carla was really not Carla but Carlo(s)--her letters falling like leaves from the trans- gendered Q’abala Lemon Tree--which is why the others' letters had to arrive: to explain her transformations, her personae and her disappearance.

They came with the words of The Future Guardian of the Letters, who first cited real poets--Amiri Baraka, Wallace Stevens, Emily Dickinson, George Oppen--as who they were in fact and imagination and then who they gave themselves up to be, breathing, through their poetry.

But the real poets gave way to avatars. They came in the form of the Forsworn Author; the Savior Editor of The Shadowy Review of Chicago; the Critic as the Bloom off the Rose dead man wandering among the NY poets of the Tribe of John, who returned us to Carla, the letter b., the anagram of the silent Hollywood-sexed film star, Clara Bow, and kneeling before her, subject to blowback, the fake Mexican scholar, Carlos b. Carlos Suares (discoverer of the wine-dark Sephardic poet, Señor al-Quala).

In order to counter the crazed polemics of the fixed identity politics of the time, these more equally craving heteronymns came in peace to have their say. Like James Baldwin, who spoke of Identity as “the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self”, they also thought “itbest that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which one's nakedness can always be felt….”

Through it all, the real names of Olson and Yépez (or any other poet gang-lander who defended them), miraculously vanished under the multiple imaginations and vulnerabilities of the others, who wanted to talk only about multiplying the possibilities for poetry or about a future era reminiscent of certain Arabic verse traditions when the signature of a poet was how well the measured sounds of her poetry could contest the authority of the tribe rather than bow to it.

So under the shadows of multiple names, and on the trail of an era obsessed with the really tribal, these others came as a dust-clouded troupe of vagrants acting out a midsummer night’s dream of the present poetic polis where poets who were once enemies might soon take the stage as comrades.

August 28, 2015

The Sky Looks Like a Big Blue Bruise

From the top of

my inverted bucket

I’m falling—good news!—

into water too shallow to reflect

this poem or the face

of its author who’s been eating

something sticky like pussy or cotton

candy I do declare

it’s cooler in water languidly

to spread one’s fingers and toes

and float like a cloud or

Samuel Taylor Coleridge pretending

in his head to be Wordsworth

on a soft autumn day

assisted by laudanum

climbing into a daffodil cup

and snoozing away the day late for dinner

who cares it’s the dream of STC

meanwhile Dorothy Wordsworth’s

a better writer than anybody as everybody

knows she’s too smart to confine

herself to flowers or buckets

the sky is maybe big enough for her

fleecing over Grasmere

same sky with a difference over me

in Chicago Lincoln Park on a bicycle

did the Romantics have bicycles and if not why not

can you picture Keats yes Shelley yes

Mary and Percy both but Byron not so much

Southey sold bicycles

the Lambs rode a tandem

in later years Mary rode a Dutch model with a bucket up front

in which to tumble hearts of lovers

like Percy and myself and also

her MFA we’re back to buckets

comedians call that a callback

but I’m not being funny when I ride with my head in a sky

discolored for once by ardor I can’t say ardor

when what I really wrote was carbon

if we could see how we’re cooking up the earth

the way my dad grilled burgers how mesmerizing

to watch him the yard growing up in New Jersey

the charcoal heat rippling

the very air the air that makes things visible

that makes possible speaking or laughing

when you don’t have air you can’t smoke opium

or one of my mom’s Salems

she’s dead now so’s

the 20th century of poems that look like this

poems of the future will be for sharing

poetry will be truly free like

water or money

because the alternative is truly terrible

and people have better sense

than to go soak their heads in buckets

individual pails of supercooled air

just because other people told us to

oh well good night New York School

good night Chicago

good night Christine

this is my self-portrait wearing a bucket

smiling mysterious as Mona Lisa

and if the sky resembles human skin

of the face maybe above the cheekbone

that registers trauma most easily feeling

it too well what can I do

May 25, 2015

Lyric Cosmology

Two lyric traditions: direct expression of subjectivity (Romanticism) vs. the persona (Modernism). The first is cosmological because it presents the self in passionate negotiation with a universe it takes to be natural. As Nature withers away as a source of meaning, the fundamentally mimetic and narratological persona lyric takes over: wearing a mask it seeks to expose the masks of social meaning. After 1989 the postmodern lyric goes even farther into the capitalist abandonment of political subjectivity, leaving us with a pure consumerist poetics in which the absence of value is no longer a scandal, but the void we swim in, untouched and untouchable by others.

To resuscitate the subjective lyric cannot mean yielding to a regressive dream of a unified Nature. Instead, subjectivity must be pluralized: the speaking self of the poet encounters and responds to other speaking selves, not all of them human, none of them "primitive" (there can be no more leech-gatherers seen as "closer" to the universal Nature and subjected to the social poet's interrogations). The practicioner of subjective lyric may borrow techniques from ethnography, as Charles Olson does, but must operate less as anthropologist than "archaeologist of morning": that is, as co-active and cooperative with the more-than-human socius he poetically encounters, and not writing as the bearer of an imperial universalizing "scientific" objectivity.

What is most valuable and unique to the lyric, I believe--a value coextensive with capitalist propaganda about lyric's valuelessness--is its built-in refusal of anything resembling an "objective" stance. Lyric offers a form of diplomacy: it presents a speaking self in productive tension with the real and potential subjectivities of others. The lyric speaker has a passion for the other, in every sense of that word: suffering, ecstasy, eroticism, sacrifice.

In the present postmodern environment the self as bearer of value has been almost obliterated. People of color, LGBTQ folk, disabled people, and women are at best tolerated by the regime, largely if not exclusively for their value as consumers and as markets (capitalism trumps, barely, the white supremacist patriarchy that predates it, and this is the true meaning of "liberalism"). But the selves of white males are also empty, non-sites of the vast privilege accumulated on their behalf, lashing out reflexively whenever that privilege are challenged, treating every presentation of subjectivity--perhaps even their own, since subjectivity is inherently messy, contradictory, and emergent from relations with others--as an existential threat.

The value of the self, as more than a counter in the lyric game, is yet to be (re)discovered. Even more deeply suppressed is the possibility of collective subjectivities. And there is, after all, a real danger that outside the regime of tolerance, without developing the passion for otherness that is intrinsic to lyric, we will find ourselves in a state of total war. (As opposed to the war that, to paraphrase William Gibson, is already here, but unevenly distributed.)

I return to the poetry of Olson and Duncan because in their passion for cosmos and polis as emergent territories (as opposed to what's supposedly simply stable and already there) they have kept the flame of subjectivity--as something to be ventured, tested, and risked--alive. Contemporary poets who come out of that tradition often come armed with the experience of a passionate collectivity behind them: I think of Lisa Robertson's feminism or Peter O'Leary's Catholicism or Nathaniel Mackey's deep engagements with jazz and the Black Arts Movement. It may be much harder for those of us who do not have such backgrounds to wager everything on the subjective lyric, rather than hiding behind masks of irony or dictate faux-objective political critiques. Well, begin from that ground where you are already most engaged, most implicated. It might be the workplace, or the family, or the university, or the military. We are none of us isolatos when we speak from the "I."

May 20, 2015

The Shield of Achilles

In the Iliad Achilles’ mother Thetis appeals to "the artist-god" Hesphaetus to forge new weapons and armor for her son after the death of Patroclus, who was wearing his lover’s armor when Hector killed him. The new armor includes a marvelous shield, and the extensive description that Homer provides for it is generally cited as the first example of ekphrasis (literally “to describe out”) in the Western literary tradition. But even as it inaugurates the tradition of poems that describe or interact with works of art (Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts” being one of the most famous), it swerves from that tradition, as a poem within a poem describing a work of art that never existed and never will exist.

The Shield of Achilles renders in impossible detail every dimension of the civilization that the Greeks and Trojans are battling for. It includes images of the country and the city, sowing and harvest, peace and war, and even a court of law, adjudicating "a townsman slain" in Alexander Pope's translation. It is a dialectical image of what the warriors on the field destroy by defending, or defend by destroying. When Thetis brings it to Achilles' camp the assembled rank and file are awed and terrified by it: "Cold tremblings took the Myrmidons; none durst sustain, all fear'd / T'oppose their eyes." But the sight of it rouses Achilles to intenser fury: "Stern Anger enter'd. From his eyes (as if the day-star rose) / A radiance, terrifying men, did all the state enclose." He puts on the armor and goes out to extract his revenge from Hector.

Police officers are the bearers of that "radiance"; it is their task to "all the state enclose." They commonly refer to the badges they wear as "shields," and very often those shields are designed with emblems of the municipality they have sworn to serve and protect. When an officer dies in the line of duty others will commonly put a black band across the shield, symbolically marking the mourning not just of the police, but of the city that has lost one of its defenders.

When I saw the video of Walter Scott running from the man who killed him, Officer Michael Slager of the North Charleston, South Carolina police department, I thought of Hector's flight from Achilles, and the explanation Hector offers for this on the point of death. He has just begged Achilles to restore his, Hector's body, to his family, and Achilles has sneeringly replied that he intends to deface Hector's corpse. Here's how George Chapman renders Hector's last words:

He (dying) said: “I (knowing thee well) foresaw

Thy now tried tyrannie, nor hop’t for any other law,

Of nature, or of nations: and that feare forc’t much more

Than death my flight, which never toucht at Hector’s foote before.

A soule of iron informes thee. Marke, what vengeance th’ equall fates

Will give me of thee for this rage, when in the Scaen gates

Phoebus and Paris meete with thee.”

There is no "law, / Of nature, or of nations" that can defend Hector's body from Achilles' desecration of it, and it was this desecration--the most extreme possibility of social death--not Achilles himself, that Hector fled. The bearer of the shield of civilization stands utterly outside civilization and makes a mockery of its laws. The Shield of Achilles becomes obscene, an emblem of the Iliad itself as "poem of force," which as Simone Weill remarked, is terrible because it turns human bodies and human beings into things.

It is easy to condemn the actions of the police officers who have murdered unarmed black men and children. These murders have been made visible, and so condemnable, not by any new insight into the racist structures of our society, but by technology. The very thing that some hope will bring about a new access of justice--through police body cameras, for instance--is the thing that holds us separate from the actions of the cops and makes it possible to cling to the narrative of "a few bad apples."

It is harder to look into the mirror that is the Shield of Achilles, the shield of civilization that every sworn police officer wears on his or her uniform, his or her armor. It is harder still to recognize that the makers of art, we who fancy ourselves somehow outside the civilization that we routinely criticize, have had a hand in forging that shield.

There is widespread condemnation today of the actions of Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place, leaders of the conceptual poetry movement in this country, for the reproductions of racism in some of their recent artworks. Conceptual poetry in my view has never moved far from Duchamp's readymade, and Goldsmith and Place have brought the stinking urinal of racism into the realm of art. In my view they have shown terrible insensitivity to the people of color that are implicitly excluded from the elite white audiences that both poets routinely address themselves to. It is the exclusion of that audience--that inability to recognize the faces of people of color as reflected in the shield of our civilization--that is I suspect more hurtful than anything they've actually done or said. They haven't actually desecrated black bodies. But they've rendered them invisible, and I am afraid that continued focus on these two poets only reinforces that invisiblity.

Place and Goldsmith have reforged the shield, represented its mirror to us in the name of critique. They say: white supremacy exists, look at it. But the manner in which they present their work, and the manner in which they defend it, runs the risk of not simply representing white supremacy, but reproducing it.

Why should any of us be shocked to discover that the racist structures that condition American society are reproduced, down to the finest detail, in the hothouse world of poetry? What makes poets so special? Why wouldn't poets, like police, in their zealous defense of civilized values, injure and exclude?

It would be easy to get Biblical again here and say to all the poets I know, "why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother's eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?" Well, that shield is certainly dazzling. And to recognize, as the Myrmidons must have recognized, that war (and not just any act of war, but a surprise attack), and justice (but is it justice, or only procedure) are intrinsic to our civilization as we've constructed it--well, those are terrible things to face. Here is Pope's rendition of the scene of law as depicted on Achilles' shield:

There in the forum swarm a numerous train;The subject of debate, a townsman slain:

One pleads the fine discharged, which one denied,

And bade the public and the laws decide:

The witness is produced on either hand:

For this, or that, the partial people stand:

The appointed heralds still the noisy bands,

And form a ring, with sceptres in their hands:

On seats of stone, within the sacred place,

The reverend elders nodded o’er the case;

Alternate, each the attesting sceptre took,

And rising solemn, each his sentence spoke

Two golden talents lay amidst, in sight,

The prize of him who best adjudged the right.

It's an ambiguous scene. On the one hand it's a form of civic peace: instead of Orestean revenge, an eye for an eye, a court of "reverend elders" will decide on the killer's culpability. On the other hand, these elders don't seem particularly alert ("nodded o'er the case"), even as their "appointed heralds still the noisy bands" of people that might otherwise start a riot--or an uprising--in response to the townsman's death. Ultimately it's money--"golden talents"--that will decide "who best adjudged the right" of the case. We have law, we have order--heralds, police. But not justice.

When I think of the task we face, as people of conscience trying to imagine justice in an unjust, corrupt, and racist society, in which every value is subject to the "creative destructions" of rampant capitalism--I think we could do worse than start from the place the Myrmidons begin, in fear and trembling. That doesn't mean we run away, or hide, or don't make art, even risky art. It simply means we act in full recognition of our responsibilities. That we keep "the ability to respond," as Robert Duncan put it. That we don't just dump our work into the public sphere--we defend it. Or recognize and acknowledge when it's indefensible.

The Shield of Achilles cannot defend Achilles' heel.

May 15, 2015

Before Spring: A Notebook

The instinct for thought before it finds expression. (Gillian Conoley on her recent translation of Henri Michaux.) Why privilege this? For the sake of the poem inside the poem. If I don't detect its presence the poem seems trifling, "lite," an enraging waste of time.

What can Judith Balso possibly mean by "figures of thought"?

Perhaps no connection between what one writes and the activities of one's so-called "inner life."

So, first, do no harm. (To the ineffable).

In awe of the simplicity and purity of Lisa Robertson's Cinema of the Present--its form, that is. The content as usual is philosophically sophisticated, playful, and complex. Her great subject continues to be the attempt to harmonize, or maybe lyricize, politics and aesthetics, the individual (woman) and the collective (women?).

Clear plastic bag of wind like a bubble of light tumbles by.

An image for this poetry: a sparkling jellyfish cloud in thin mental air with stinging tentacles dropping and trailing their tips on the ground. (William James, with stingers.)

It is enough, maybe, to keep company with sentences.

Balso: "a thought capable of holding together the contingency of the universe and the possibility of a collective and projected figure of humanity."

We can't seem to imagine the earth, only heaven and hell. (Stevens: "The great poems of heaven and hell have been written and the great poem of the earth remains to be written.") Easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, etc.

False tranquility of the corpse--the extrinsic life of microbes and maggots reanimates it. Finally the false peace of bone, beginning its slow irretrievable movement into soil and rock. Writing this in the understanding that when this happens to my body, it will no longer be mine. The life of consciousness shunts onto a new track at the moment of physical death. Where that track leads no one knows, but one thing is certain: it leaves the body as we knew it behind.

Afterlife of consciousness almost irrelevant and a matter of karma. As I collapse into the isolation of the brain, I take with me all the good and evil of my life--that which I lived in the world.

Lisa Robertson: "Within the concept of the present, the figure-ground relationship effaced itself."

f a t e

prisoner of passion

limits

contraint predicates freedom (image of thought)

From that into a definition: the present, or the experience of presence, is prior to figure-ground distinctions.

Hell as city in Dante, a parody of Florence. Heaven is also Florence.

LR: "Do these experiences of thought and reading persist and accumulate? Or is most of it lost, only to be circled back to and rediscovered?"

(Ambivalence of intellect. The arbitrary.)

(Back and forth between poetry and Walking Dead recaps.)

(A phrase that comes from nowhere: impaled flesh-plug.)

LR: "And what is the subject but a stitching?" To the object, to context.

Perpetual warring imaginations: the French conceptual with its seductive hypostases; the Anglo-Saxon embedded particulars. Verticality v. horizontality.

Latinate conceptual authority / Anglo-Saxon popular particulars

No commons of the concept. The people can never enter authority without ceasing to be themselves.

Syntax is no ontology but it functions like one. Cases of mistaken identity are common.

Always midst and muddle. I long to step out of things, to step into the sacred pause between finishing and beginning.

LR: "What's natural, what's social, what's intuitive?"

(Another phrase: fur of transience)

What you love is the white space islanding each of LR's statements, inviting the reader to fill in the significance, ramifications, and possible contexts of each.

LR's figure for lyric: "ancient ego nectar."

"the noticed friction between thinking and perceiving"

(eros of a sincere mind)

LR: "form requires of you a reticence." My contrary urges toward purity, the stripped (verse) and the prolix overthrow of prose fiction (or the fictionesque).

Libidinal investment in forms and genres--strategic.

LR: "the prosody of being misapprehended"

Philosophical difficulty, referential difficulty. My hyperliteracy and compulsion to recycle and elude. LR mostly free of that--impressive reticence. The difficulty is literally in my mind.

LR: "You think with plants and rags, with prepositional inadequacy, with improvised throat of sorrow."

(Confidence ebbs and flows. In the ebbs it's best to read. Translate a little.)

Desire to bring French into English. Stevens: "French and English constitute a single language."

Romantic isolation of a cottage or a cabin. But instead of long walks, a logpile, brilliant insights by firelight. I envision: depression, dirt in the sheets, chronic masturbation, a poor diet.

Religion inscribes the divine in dailiness. Keeping kosher keeps G-d before the mind at every meal, in every detail of the menu. It's practical. There's an intrinsic Protestant quality to secularism since the secularist deprives himself of ritual and is left with the emptiness the Protestant fills purely by faith. Empty pews, clapboard churches.

LR: "You carried the great discovery of poetry as freedom, not form."

Place in the sun. Piece of the pie. Sunny side of the street.

"Soul" is generally used in a unitary way, to indicate the state of the self at its least divided. But I hear pain of division in it--"soul music"--the longing for unity that can only be achieved by opening to otherness. The soul is tragic or openness to tragedy, to a fundamental human homelessness.

I envy the achieved simplicity of form in Cinema of the Present. But it's the achievement that makes it look simple. Surely, in composition, in the middle, she must have felt moments of muddle, in spite of the perfect simplicity of the book's visible constraints--roman type alternating with italic type, the italic type proceeding more or less in alphabetical order, so that sentences recur, sometimes close to each other and sometimes at a great distance, creating a multivoiced and fugal effect. I look at my own works in progress and wish for a hill to climb high enough to catch a glimpse of their final forms. But this is impossible, as it must have been for LR: I'm in the middle and the only way out (or up, or down) is through.

LR: "You would like thought to release something other than laboratory conditions." Thought, as abstraction, reduces too much, seems all but incapable of grasping the blooming confusion of particulars in which our bodies, as opposed to our habitually Cartesian minds, are very much at home.

tragitopia - the place of goats

A strong sense of theater in LR. Poetry as mental theater in which to try out little dramas of language and thought. "You use speech to decorate duration for somebody. You stop just before it becomes a shape."

Cafe: Tall striding high-headed white pompadoured Malcolm MacDowell-ish man reading a volume of Wittgenstein's lectures, standing up at the counter.

Cafe: Young woman in a low-cut peach lacy blouse sitting erect before a textbook on organic chemistry listening to whatever's on her earbuds with great concentration.

What is "lyric obscentiy," Lisa? The unspeakability of the ipsus? "The I-speaker on your silken rupture spills into history."

Lyric research. Laboratory of the speaking I.

LR: "You're bent to a book as the uprising unfurls."

Shadows and terrors. Misdirected rage. Jews the scapegoats of modernity. When it's capitalism and unjust systems of distribution that need to be attacked.

Rilke: "Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love."

Desire to withdraw, vita contemplativa. History knocking, trying to pretend I don't hear. Europe is fading. Israel withdraws from democracy. Anti-semitism is real.

Hoffnung, wo ist?

At the Art Institute I rest for a moment in the eternal gilded age of the Sargent portraits, where human graces for a while rise to the surface of memory and all costs are hidden.

There are historical moments, anchors in time, achieved through aesthetic perception, that are my only chance at perspective, for grasping the crisis of the present. The turn of the twentieth century, the first decade after WWII, the Seventies. Romanticizing the great risk. Pasolini: Harsh / climate, sweet history. Mandelstam: "the most dangerous, intricate, and criminal century."

Needing more diverse means of registering citation in my poems. I don't like quotatio marks. But I can't use italics for everything. Small caps?

Balso asking "in what manner the past can return within the present" of Mandelstam and Dante.

As a woman LR invests in appearing, wrestles with her inability to separate from the spectacle of femininity in order to speak. "You wore the dress as payment for entrance to the symbolic order."

Getting in on the ground floor of the Logos as factory of value. Not value in itself but the means of production. Content.

LR: "To think in a bed in a hotel in an unfamiliar city is your dream."

Running out the clock of this notebook.

The Dante Sonata. When did the classical concert become infected by pain and dread? Light of unresolution.

Cafe: Man with a Slavic accent telling another about William S. Burroughs and how addiction leads to long life, struggle with the self, replacing the self--"it's like leeches." I think of Maggie Nelson's The Argonauts. "I only like nonfiction," the other guy says.

Man seeks spiritual compensation for social deficits. And the reverse.

Meant that to sound like a want ad.

A man alone makes no nomos.

Poetry as I have it from Stevens, from Ashbery, accepting nostalgia but not resting in nostalgia; resorting less to historical myths than the poet's own rough-and-ready ironized frangible myth-making--Crispin, the new spirit, et al--which are like chess pieces made of glass, acceptable for play but not in themselves final or monumental. The game has the goal of restoring the earth to the player and the player to the earth.

LR: "This is where thinking could become nature, where both are only incomplete."

Cafe: A man with a Bible behaves as I do with this copy of the Collected Poems: he doesn't read, he rereads, scrutinizes, writes in notebook, feels himself observed. He is in pursuit of his own soul. I likewise? I, forgetful of my task, face lit by sunlight on decayed piles of snow?

Mom, I’m still in space, rocking imperceptibly, systole and diastole of persisting beyond you and your death, toward my own death, toward my daughter-your-grandaughter’s frail horizon. The day she came into language remembers you.

"Even the dead will not be safe--"

(doesn't end)

May 7, 2015

Becoming Yourself: </i#x3E;

Last night I went down to the majestic Music Box Theatre for a Chicago Film Critics Festival screening of James Ponsoldt's new film The End of the Tour, a film based on David Lipsky's book about the five days he spent interviewing David Foster Wallace for a Rolling Stone profile that was never published. It's a subdued and plotless film, anchored for this viewer by its deadly accurate portrayal of the neuroses and egos of two writers, one of whom is wildly successful (but profoundly fragile), the other overflowing with a toxic blend of reverence and envy, wielding a handheld tape recorder sometimes like a shield, sometimes like a dagger.

Films about writers are notoriously hard to pull off: there's nothing visually interesting about watching someone sit at a keyboard or scribble in a notebook or stare thoughtfully out of windows. Ponsoldt's way around this is first of all not to have made a conventional cradle-to-grave biopic, though the film is framed by the news of Wallace's suicide and Lipsky's response to it, which results in his book Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace. Ponsoldt takes his cue from Lipsky and gives us a kind of buddy movie in which the buddies can't erase a mutual suspicion of each other's motives, even though as nerdy white guys with a literary bent they are more similar to each other than not. The film is devoid of literary content as such, but the glimpses we get of a writer's life on and off the road--the room full of his own books, the cheerfully indifferent local publicist (mischievously performed by Joan Cusack), the readings whose attendance or lack thereof is precisely indexed to the author's fame--are instantly recognizable to anyone who's ever published a book.

The only other film I can think of that's as successful at portraying what it's like to be a writer in America (which is very different from portraying writing) is Barton Fink. The Coen brothers, of course, are scabrous and satirical where Ponsoldt is more gently rueful, but both films do a remarkable job of conveying the peculiar mix of grandiosity and self-loathing that afflicts most of the writers I've known. The two Davids of Ponsoldt's film curiously parallel the roles played by the two Johns (Turturro and Goodman) of Barton Fink: it's as though they take turns revealing to each other their most fragile aspirations and the terrible obstacles to realizing them. I'll show YOU the life of the mind!

I have never been a member of the DFW cult, though I love some of his essays, but the film confirms in me mingled feelings of affection, protectiveness, and sadness for the man. Jason Segel's performance is marvelously subtle, completely recognizable without being an impersonation, and he conveys a tremendous amount of mental activity between and to one side of the stream of words he spills (mostly taken, Ponsoldt says, word for word from Lipsky's tapes). Jesse Eisenberg is more typically Jesse Eisenberg-ian--in the Q&A Ponsoldt said he reminded him of Ratso Rizzo--which makes him all the more painful to identify with, as I inevitably did, in his desperation to have something of Wallace's genius and success somehow rub off on him.

There's an amazing scene toward the end when Lipsky, left alone for a moment in Wallace's shambling one-story ranch house, runs around with his tape recorder to his lips itemizing the objects and furnishings ("a bookish frathouse" is his accurate summary). It's a creepy, stalkerish move, but in the film it resonates with love and poignance, particularly for we the viewers who also wish we could capture the man, now lost to us forever. Loss is woven into the texture of the film--there's an early shot of 1998 New York with the Twin Towers in it, and this is paired with a scene later on in which Wallace muses presciently to Lipsky about what would be terrible enough to make someone want to jump from a burning building. I was reminded somehow of Man on Wire, a film for which 9/11 provides a ghostly frame, though the event itself is never mentioned.

There's something undeniably ghoulish about the film's Lipsky: at the end of the film we see him reading from his book about Wallace to a much fuller room than the one to which he read from his own novel at the beginning. He has elbowed his way into the DFW story and become inseparable from it: reality hunger, indeed! I can't help but read this as a comment on how the literary stakes have shifted in the past twenty years: prestige no longer lies with the postmodern phantasmagoria of long novels like Infinite Jest but with the postmodern transparencies of books that blur the line between fiction and nonfiction (I think inevitably of Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose six-volume My Struggle could not only beat up Infinite Jest in the playground but surround it, the way the Sinister Six surrounds Spider-Man). Is this the zombification of fiction? Or just an honest account of how anyone becomes a writer: by seeking to absorb the spirit of whatever other writer first began to make writing seem like a living possibility?

In a way, you're much luckier to cathect upon a dead giant like Joyce or Woolf than if you fall for a living writer: you will never catch up with the great dead until--maybe--you are dead yourself. (I think of Jack Spicer's famous last words to Robin Blaser: "My vocabulary did this to me--your love will let you go on.") Lipsky is done for the moment he reads Infinite Jest (there's a sharp early scene where we see him reading it, wanting to dismiss it, and then resigning himself to its brilliance with a simple sudden "Shit!"); is it maybe the case that he can only become himself as a writer once Wallace is dead? I will probably have to read his book to find out.