Christopher Lloyd's Blog, page 2

September 26, 2013

It’s a small small world…

I AM BACK in Japan. This time just for a week, but it’s action packed. Six lectures in all, but the final one on Tuesday is the one that matters most. It’s at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, in front of an audience of about 600, where I get to give my take on the future of planet, life and people over the next 1,000 years in the light of a warming climate and the relentless rise in human populations.

Hmmm… It’s something I have thought about quite a lot over the last few years. Big history helps – at least I hope so – since hindsight and foresight are remarkably similar. Looking into the future means just turning your head the other way. It is no more or less certain than the past, actually. Big themes, interconnected disciplines, and generalisations based on rational foundations are the best guides, and I think the chances of getting it ‘right’ are about the same. In the end history and futurology are ultimately matters of opinion and interpretation made more or less convincing by argument based on selected evidence.

Perhaps it is our ability to evaluate the past or speculate on the future that especially distinguishes human brains. That’s where I think we differ from dogs. Flossie, our westie, is infinitely more present or conscious in the here and now than I am, or ever will be. Her sniffing, her focus on the moment are qualities that matter most in the wild, in the state of nature, where survival is a matter of the utmost care.

Flossie, our westie, is infinitely more present or conscious in the here and now than I am, or ever will be

Imagine a tiger ready to pounce on its prey – just one careless move, a snapped twig, is all that stands between a hearty meal and frustrated hunger. Nothing like lunch (or the lack of it) can focus the mind better on being aware in the present. And the prospect of being someone else’s lunch is no less mind sharpening….

But we humans are different. Civilisation has numbed our sense of the here and now. I really think we are, in this way, so much duller in the heads than our hunter-gathering ancestors. Being safe from instant predation by wild attacks masks us from the need to worry about being eaten in an instant if we tread carelessly on that twig in a wood. As a result our swollen cerebellum turns itself on the past (and the future) in its bid to avoid being bored. Therefore, we gain hindsight and foresight – from which come a sense of time, history and destiny. Perhaps that makes us unique amongst living beings?

If you happened to be listening to the PM programme on Radio 4 last week you may have heard an interview featuring Edmund Burke – the great TV presenter of the classic 1970s history series Connections. Quite why he popped up again last week I can’t quite recall, but his habit of interlinking knowledge is something I find appealing. He was being interviewed about the future – the same topic I am readying myself to address next week: My ears instantly picked up – as if a twig snapped.

Burke declined to give his view on the next 10 – 20 years – it’s simply too close to the present to be able to predict. But reach out 40 years or so and the horizon begins to get a little clearer. I take his point.

His verdict was astonishing. There was none of that climate change, end of the world, rising sea levels, bird flu, great famine crisis kind of stuff. In 40 years time technology will have come, like Polish King Jan Sobieski III, in just the nick of time to rescue modern civilisation from drowning in its own excrement. By then science will have invented something so revolutionary that it will, at a stroke, destroy capitalism and save the planet at one and the same time.

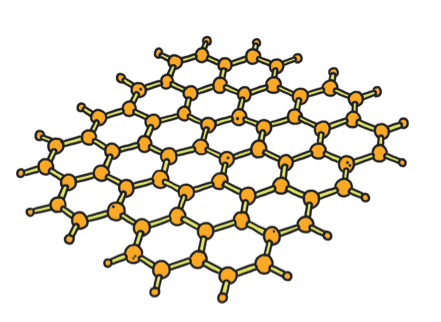

Look on ye mighty and despair at the nanofactory!

It’s a machine – based around today’s quantum tunnelling microscope technology – that will be able to manipulate matter at the atomic level and arrange atoms of a given element or compound into an exact copy of anything – anything – you want to consume, own or just marvel at. It’s a kind of super-souped up version of today’s 3D printers.

Food is almost entirely made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Just feed these common elements into the nanofactory and it will build – atom by atom – according to a scanned image or downloaded design – anything you want to eat. A cucumber – a steak – a glass of chateauneuf du pape. Perhaps you could even make your lunch out of excrement – that’s got most of the ingredients…

The idea isn’t so completely bonkers and 40 years is a long way out, given today’s rate of technology innovation. Much of today’s food is synthetic already – from vanillin to corn flakes – thanks to the ubiquitous corn fructose syrup.

But the nanofactory will be able make anything all in the comfort of your own kitchen – possessions, computers, clothes, toys, furniture….

‘Just imagine!’ marvelled Burke.

Once the consumer has such technology there will be no market (except I guess for the nanofactories themselves) because there will be no need to buy stuff – you just make everything on demand. There will be no hunger, no inequality, no resource crisis. Everything will be recycled, remanufactured from the bottom up to make whatever happens to take our fancy. Today’s miseries and tomorrow’s forebodings gone in a flash of genius!

Once the consumer has such technology there will be no market because there will be no need to buy stuff

But as I switched off the car engine and the radio fell quiet, a feeling of inevitability soon returned – despite Burke’s irrepressible optimism. The second law of thermodynamics always spoils the party! How much energy would it take to make all these things? And where is all the energy going to come from to make, let alone power, 10 billion nanofactories all spewing out commodities to satisfy our never ending fetishes…?

All of which brings me back to Japan, now without nuclear power and facing its biggest economic challenge for a generation thanks to the ongoing disaster at Fukushima.

I shan’t be mentioning Mr Burke at my talk on Tuesday next week – although if any great nation can make this nanomiracle into a reality, I guess it will be the Japanese. Still, I find the idea intriguing – perhaps it is a possible solution to the world’s ills. Whatever, it would make the basis of a cracking novel if only I had the skills of an H.G. Wells!

September 14, 2013

If a child gets bored at school, blame the system

Christopher Lloyd learning together with his children at home in Kent

SHE LOVED READING. She always asked questions. Her mind was a cauldron of effervescent eagerness, never idling, ever curious…

That was ten years ago when Matilda, our eldest daughter, then aged nearly 7, was brimming with excitement about heading off into a new academic year at her school in Kent.

But over the course of that term she turned into a completely different child. She stopped reading. Getting ready for school became a daily battle. It was as if her innate curiosity had flipped, like a coin, into angry, bitter complaint. Something was terribly wrong…..

In a word, she was bored – partly because she was being given mind-numbingly repetitive work. Matilda’s teacher insisted there wasn’t a problem as she was doing well in her tests. The head teacher, who loyally backed up her colleague, told us not to fuss, it was a phase that would soon pass.

But seeing our fizz-ball of a daughter literally fizzle out within just a few weeks of changing class was too appalling for us to see. We felt compelled to do something.

We tried looking for another school – both in the private and state sectors. To our astonishment, none offered us much comfort. They talked out about wonderful food, superlative facilities, excellence in health and safety, anti-bullying and, of course, their great results, but none ever volunteered the idea of never condoning a bored child.

*****

WE HAD NO IDEA that the UK boasts one of the highest numbers of home educated children in the developed world. As many as 100,000 children are educated not at school, but by their parents.

Initially, we decided to home educate for a year while we searched for a more creative, stimulating school for Matilda and her younger sister Verity. We created a school room at home. We found a ready-made curriculum on the Web and divided the day into a timetable. I led on Science while my wife plunged into Music, Maths, History and English. We found a French tutor, a tennis coach and the girls joined local dance and drama groups. I moved to a four-day working week while my wife threw herself into home educating full time.

After the initial novelty of not going to school wore off (perhaps it took about a week or two?) everyone’s patience began to wear thin, frustration boiled over all too frequently, attention spans shortened and, to cap it all, Matilda said she found it just like being at school but at home! In a word: boring.

But we knew that only a few months ago Matilda’s world was a wonderland of curiosity and fascination. We were desperate to find a way back to that place. And so after reading a few books written by people with similar experiences, and a great deal of discussion, we changed tack completely, sat Matilda down, looked her straight in the eyes and asked her a question which no-one had ever bothered to ask her before.

Matilda said she found it just like being at school but at home! In a word: boring.

“Matilda – what are YOU interested in?”

It’s sounds crazy – but think about it – our educational system NEVER asks that question.

Rather it says that at 11.30 on Tuesdays you will do biology, and in term 2 of year 6 you will be doing photosynthesis. Why? Because it says so in the curriculum. There is no connection or relevance to the child’s life and no reason why this fragment of knowledge should be studied at the time on that day other than that is suits adults for it to be so.

“PENGUINS!!!”

What?

“I want to learn all about PENGUINS”

And so began our new educational adventure.

****

WE VISIT London Zoo. We do a project about the Antarctic, where the penguins live, and discover that they huddle together to keep warm.

“Now imagine two groups of penguins and if, say, THIRTEEN penguins leave one group and join the other……”

“How many penguins are now left in the first group?”

We study ice – it’s fascinating because penguins live on ice.

What is it? Ice, water, steam – all the same substance but at different temperatures they change into different states. My wife takes Matilda outside after the rain has stopped. They measure puddles together and see how long it takes for each to disappear. Where did all that water go? In the ground? In the air? It makes so much more sense to discuss the water cycle just after it has been raining!

How about a historical story to do with ice? Do you know about Scott and his race to be the first man to the South Pole? (which is where penguins live….). How many miles did he have to travel to get there?

It makes so much more sense to discuss the water cycle just after it has been raining!

We soon realise that the whole fragmented, bitty, contrived curriculum we had downloaded from the Internet could, with a little imagination, be covered through whatever topics most interested the children.

So I quit my job. We buy a camper van, travel around Europe for four months and end up home-educating both our daughters until they are 11.

*****

During our big campervan trip I wanted to buy a book that would connect all the subjects in the curriculum together – like the penguins did for Matilda – but whenever I went into a bookshop I was presented with a stark choice. Go into the Science section and read about the formation of the world until the arrival of two legged hominids. Or go in to the History section and read about the beginning of civilisations in Mesopotamia about 7,000 years ago – as if nothing had happened before!

Surprised to find no single book connecting natural and human history existed, I decided (needing to find a job anyway by this time) to have a go at writing it myself. What on Earth Happened? The complete story of planet, life and people from the Big Bang to the present day was published by Bloomsbury in 2008.

But an interdisciplinary narrative in 180,000 words is never going to appeal to that many young people – especially those who struggle with lots of words in books.

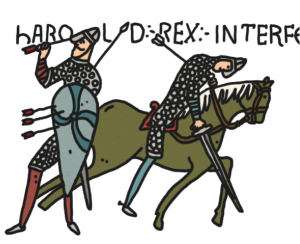

So, I wondered, how big narratives were told before people could read and write. My mind turned from William the Conqueror’s Bayeux Tapestry to biblical stories depicted on the stained glass windows of gothic cathedrals. Then I was shown a Victorian attempt at a visual chronology of world history (by Edmund Hull beginning with Adam and Eve).

So, I wondered, how big narratives were told before people could read and write.

Would it be possible to construct an up-to-date version, giving a visual overview of the story of world history in 1,000 pictures and captions on a 13.7 billion year timeline? The aim would be to connect science and history – in fact the whole curriculum from primordial cosmology to modern religious conflict - into a single, visual narrative.

This is how the A3 sized What on Earth? Wallbook, which can be read like a book or folded out into a 2.3m long wallchart, was conceived. Being spineless means several people can read at once and a curious child can roam wherever their fancy takes them– beginning, middle, end, top or bottom – without ever getting lost since the timeline keeps everything in chronological context. Best of all you can discover that when Henry VIII is on the throne, in China they are building their second Great Wall; the Portuguese are introducing guns into Japan and the Europeans have discovered a brave New World.

****

ONLY CONNECT – that famous dictum at the start of EM Forster novel Howard’s End – is still the best advice for anyone involved in learning and education. Connecting knowledge allows young people to follow their curiosity (penguins again), whereas chopping it up into fragments, as we mostly still do in school, presents a view of the world about as engaging as a window-pane of shattered glass. A big picture perspective provides narrative context and lateral links – essential ingredients for making information relevant and interesting.

In a world where everything changes so fast it seems crazy that we continue to base our education system on outdated Victorian structures, timetables, school bells, arbitrary subject disciplines, syllabi, curricula, rote learning and endless examinations. If a child gets bored at school, blame the system – it’s not the child who has failed.

For information about Christopher Lloyd’s What on Earth? timeline enrichment workshops for schools and cross-curricular integration INSET sessions for teachers please email [email protected] or visit www.whatoenarthbooks.com/events

This article first appeared in The Daily Telegraph on Saturday 14th September, 2013

September 13, 2013

From Stone Age to present day in one huge wallchart!

Christopher Lloyd, author of the new ‘Science & Engineering Wallbook’, explains some of the challenges of trying to tell giant stories in a non-traditional format

The What on Earth? Wallbook of Science & Engineering

Imagine spending a year working on giant jig-saw puzzle that starts in the Stone Ages and then travels through time to the present day, featuring 1,000 of the most amazing moments in the story of science and engineering…

Now try turning it into a book. That’s the journey I have just taken after putting together the latest What on Earth? Wallbook of Science & Engineering – a collaboration with London’s Science Museum and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. The story it tells is mind-bogglingly huge – nothing less than how humans have reshaped the world with their ideas and their hands over the last 10,000 years.

But a jumble of 1,000 pictures and captions all crammed onto an A3 size book that unfolds into a 2.3m long timeline could easily turn out looking like one big colossal mess. How does one go about designing and organising such a mine of information to make it look good and make sense?

The trick is to find some visual template that seems appealing from a distance but that can also pull all the detailed information into thematic order. A beam of white light travels through the first section of the timeline, containing all the dates from the stone ages until the mid seventeenth century. Then, as the Age of Enlightenment unfolds, the beam shines into a prism as Sir Isaac Newton discovers that white light is made up of all the colours in the visible spectrum. Now the date is 1680.

As the light exits the prism, the dates descend to the bottom of each page as the beam refracts into all the colours of the rainbow, from purple at the bottom to red at the top. Seven bright streams reveal seven themes of science & engineering, ranging from abstract to infinity, each one representing a change in scale: maths and measurement (abstract), physics and chemistry (atomic), biology & medicine (molecular), land and agriculture (Earth scale), building & invention (things we do with the Earth), transport & communications (connecting the Earth together) and finally sky and space (the never-ending infinity).

And for those who like a more traditional narrative treatment, 18 newspaper stories are featured on the back, covering everything from Greek engineer Archimedes leaping out of the bath, running down the streets naked shouting Eureka!, to the genius of Etienne Montgolfier, who was inspirited to build an air balloon after seeing his trouser pockets billow upwards as they dried above a burning fire.

Books should not always been trapped by spines and filed on shelves. For me, the joy of innovative book design is in finding news ways to explore telling big stories differently. Making a timeline stretch across a series of concertina folded pages means several people can read the book at once. It can be spread out on the floor, laid across a table or mounted on a wall – not trapped on a shelf or discarded in a dusty corner.

Finally, a giant version of the foldout book makes a fabulous public exhibit – a book that can double up as a piece of street art or the backdrop to a lecture about the most incredible moments along a timeline for schools, museums, literary festivals and just about any curious human who wants to know What on Earth Happened?

This article first appeared in The Telegraph Online on 12th September 2013

Please feel free the contact the author here:

[contact-form-7]

July 13, 2013

Our island nations and Mr Gove

I VERY NEARLY didn’t make it. The roads from Oakwood School, near Chichester, to just passed Guildford were fine, but then an all too typical Thursday late afternoon nightmare began to unfold on the A3 and stretched out all the way to Heathrow on the M25. I arrived at check-in 5 minutes after it had closed, my skin saved only, I reckon, by the look of total desperation on my face and my slightly askew bow tie.

Stepping off the plane and a wave of heat smacks me in the face. Within moments, sweat begins to drip down my back. Actually, I don’t mind it hot, but even by Japanese standards, so I am told, the current hot spell is off the scale. Today, I hear, temperatures are at similar record highs in the UK.

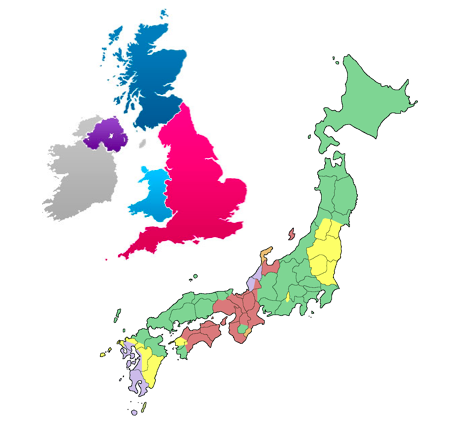

This is my second visit to Tokyo, within a year, and now I realise it is not just the current weather that seems to bind Britain and Japan. I am beginning to sense a kind of convergent evolution surrounding me as I sample, compare and contrast the culture, environment and plights of Japanese and British history.

Ostensibly there is little direct connection. Japan was never part of the British Empire . No Christians to speak of were successful in their quest for saving souls (there is even no word, I am told for ‘Bless you’ in Japanese). The language is as alien as if I had arrived on a mission to discover life on Mars. And geologically the fault lines that criss-cross the landscape – from the catastrophe of 3/11 to the predicted big one that is sometime set to rock Tokyo to its core – makes this a place with a destiny detached far off from the benign shores and shires of Blighty.

Yet, curiously, here I feel so much more at home that I have ever done when on a visit say to the US (now there’s an alien place).

How can this be?

I think I am beginning to see why.

Japan and the UK are both island nations. Our fortunes have traditionally rested on mastering the surrounding seas.A mutual fondness for feudalism has defined our cultures (samurai on the one hand, chivalrous on the other), sustained I suspect from prolonged periods of isolation from invasion. Manners and a certain reserve are hallmarks of our historic culture. Imperial ambitions unite our histories with empires mutually won, then lost. And today both of our nations still share an ongoing, profound and deep mistrust for our nearby continental neighbours (be they French / German or Chinese / Korean). We have a lot in common.

All of which makes me realise that a simple lack of historic contact is no excuse for ignoring the connections that we apparently share. I think the fact that we have far more in common than most people probably realise makes studying each other’s past just as important as studying our own. Only by looking outside and beyond ourselves can we hope to see our lot more objectively – the goal, surely, of any legitimate historical pursuit.

So Mr Gove – how about making the study of Japanese history part of your new compulsory history curriculum?

Alas, I don’t expect our views about the best way to study history converge much at all. On one level we seem to agree – I am all for learning history in context - and a chronological approach is one way to achieve that. But on another level we are as far apart as the miles currently separating me from my girls back home because I am quite sure that British history cannot and should not ever be considered as an ‘island story’ – separate and apart from the myriad interconnections and forces that have shaped our nation and culture over time.

Happily, universal condemnation of Gove’s initial proposals have taken out the most pernicious threads of his attempts to revive some monocultural national identity through a skewered teaching of history. But the thrust of history as a chain of British initiated events unleashed on ourselves and the rest of the world is still deeply woven in. When I plotted my top 10 moments from 1066 to the present day (which I presented last month at the Chalke Valley History Festival and which I list, as I promised I would, below) I found there were just as many to do with forces that shaped us as there were impacts we have had on others – human or non human.

That’s the problem with the whole idea of studying British history as a subject in itself. It begets an arrogance that’s myopic at best and chauvinist at worst. Any ‘Our Island Story’ rendition of history inevitably focuses on what we did to ourselves and our impact on the world, usually at the expense of the myriad forces that made us who we are. In an interconnected world such as we have today, mutual appreciation of the pushes and pulls of historical forces across all boundaries - national or disciplinary – is the absolute essence of it all.

So, as an antidote to Govanism, may I offer you this remarkable irony: thanks to a deep draught of what biologists term convergent evolution – our island story may probably come into sharper focus when viewed from a perspective here in Japan than ever it could back home.

Very best!

-chris

My current top 10 moments in ‘British History’ from 1066 to the present day (coat-of-many-pockets objects in parenthesis)

1) Invasion of England by Norman forces - aided by adoption of Chinese saddles / stirrups by European Medieval knights from Islamic fighters in France and Spain – (plastic stirrups)

2) Spread of Gunpowder to Europe via Islamic Spain - diffuses to England after Siege of Algeciras and used in anger for first time at the Battle of Crecy (toy gun)

3) Spread of Black Death originating in Henan Province China - leads to huge social / political change in Europe and England during 14th century (box of plasters)

4) Strategic decision by Henry VIII to plunder monasteries and build a fleet while at the same time the Chinese abandon naval power and build a wall (royal crown)

5) Statute of Monopolies, introduction of a system of patents by James 1st giving Britain pre-eminence in innovation and technology (royal seal)

6) Solving of the longitude problem by John Harrison in early 18th century - with his marine chronometer – gives British strategic navigational advantage at sea – helps build imperial power (compass)

7) Invention of high pressure steam power following successful trials of Richard Trevithick’s Puffing Devil, later harnessed by George Stephenson and his Rocket. This allows the British to exploit colonise overseas and import massive material wealth including saltpetre from India to sustain gunpowder supplies. Still today 75% of all electricity comes from steam power – (toy steam engine)

8) Rise of German power in first half of 20th century leads to eventual collapse of British Empire. Britain goes bankrupt by1974 (Postcard from Berlin)

9) Margaret Thatcher deregulates the City of London giving Britain a (probably temporary) new way of siphoning off wealth as North Sea Oil supplies dwindle (a domestic iron)

10) Instability of globalisation - Increasing inequality, overpopulation and a lack of seeing a more interconnected, holistic view of nature, science, history, economics and environment become the country’s biggest problems in common with most of the rest of the globe (witches cauldron)

June 19, 2013

1066 and all that….

NEXT WEEK I shall be speaking at the Chalk Valley History Festival. Normally I would roll out my history of the world in 60 minutes – starting with the Big Bang and running through 20 of the most amazing moments in world history to the present day. But not next week. The festival organiser, historian James Holland, has taken it upon himself to modify the title of my talk so it begins at 1066 – giving it a rather different trajectory……

NEXT WEEK I shall be speaking at the Chalk Valley History Festival. Normally I would roll out my history of the world in 60 minutes – starting with the Big Bang and running through 20 of the most amazing moments in world history to the present day. But not next week. The festival organiser, historian James Holland, has taken it upon himself to modify the title of my talk so it begins at 1066 – giving it a rather different trajectory……

Even though the change appeared in the programme without my knowledge, it is a happy tweak as now I have the chance to dwell on aspects of the past that usually skip me by at close to the speed of light.

Today I have spent a few minutes making up my mind about the 10 moments that seem to me to be the most significant in British history over the last 1,000 years, What’s so interesting is that I find my narrative quite unlike anything an English school child would ever learn at school. I suppose that occasionally they may bump into my moments or flirt with fragments of the story I will tell, but I bet they will never see it whole.

Why not? Because when British school children learn about their history they are almost presented with the story from the inside out. It’s about how we have changed the world. It’s about how our kings, queens, rulers, inventors, charlatans – how our indigenous inhabitants have made things the way they are.

External interferences are strongly discouraged – usually by simple omission. Indeed, the story almost always begins in 1066 – so that the ignominy of external interference can be got out of the way at the start, and, fortunately for us (unlike any other European country) never seriously has to be considered again. We have not been invaded since. We are an island nation, a scepter’d isle which built an empire on which the sun never set…..

Such a parochial, insular reading of “Our Island Story’ is as arrogant as it is absurd – yet the narrative is the one that dominates. I am happy to report that it won’t be the diet that the youngsters and their parents / teachers will hear next Monday.

Such a parochial, insular reading of “Our Island Story’ is as arrogant as it is absurd

So – I wonder what will my chosen 10 moments be? Who will be the heroes, what were the forces, which are the inventions? My approach is as much about the forces that have shaped Britain as the way in which Britain has shaped the world.

I think I have just about decided on my list – although I shall continue to mull until the talk at Chalk next week. Perhaps in the meantime you can tell me yours? Please email / comment away – but remember no more than 10 are allowed. Next week I shall reveal my milestones – each with an accompanying prop for the coat of many pockets, of course!

May 29, 2013

Curtanomics

I WAS LOUSY at maths in school. If anything I am even worse now. Weirdly I found basic ‘O’ level totally dull but additional maths (AO Level), when things became less arithmetic, became more intriguing. I also had a different teacher, which I suspect, made a big difference too.

I WAS LOUSY at maths in school. If anything I am even worse now. Weirdly I found basic ‘O’ level totally dull but additional maths (AO Level), when things became less arithmetic, became more intriguing. I also had a different teacher, which I suspect, made a big difference too.

But at this present moment I find myself fascinated by maths – not that I am any better at it today than I was 36 years ago – but the bottom portion of our latest Wallbook of Science & Engineering features a Maths & Measurement stream spanning from the ancient Babylonians use of Base 60 to the solving of Fermat’s last theorem (by Andrew Wiles in 1995) and beyond. I have discovered that the story of maths and its place in shaping and telling us about human cultures is truly astonishing.

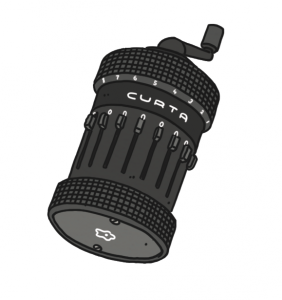

Such intrigue has been excited even further by an extraordinary device which dropped through my letter box only this week. It is a true miracle of engineering which is featured on the new Wallbook’s x-axis at c. 1945 and on the y-axis in the abstract section at the bottom, marked Maths & Measurement.

I have to thank my friend Alex Bellos, author of the fabulous Alex’s Adventures in Numberland, for introducing me to the Curta – an extraordinary analogue calculating machine devised by Jewish engineer Curt Herzstark when he was imprisoned in a Nazi prison camp during World War II.

I bought my Curta on e-bay (an internet marvel, I have to confess). Mine was made, as were all of them, in Lichtenstein shortly after the war. About the size of a pepper-grinder this small, black drum of cogs, slides and gears allows you to add, subtract, multiply and divide almost as fast as using a modern electronic calculator. Decimal points, fractions – no problem. You can even do square roots.

As a result of the Curta I have, at long last, gained my first direct experience of the joy of arithmetic. I want to multiply, add, subtract – simply for the joy of resetting the machine, adjusting the slides and pulling the circular crank to reveal the answers to sums that would take me only a fraction faster on a modern electronic calculator and ages longer using pencil and paper

So, I wonder, what is it about this small, mechanical device that makes arithmetic so infinitely more pleasurable than tapping in numbers on the calculator app on my iPhone? How bonkers would it be to do sums for no other reason than to see the answers displayed on a screen? But doing sums for no other reason than witnessing this miraculous mechanical pepper-grinder crank out the answers feels entirely legitimate.

I can think of at least two reasons that account for this polarity of feelings. I wonder if they may provide some insight as to how it might be possible to make learning maths at school more engaging for those with a less arithmetical disposition.

Doing sums for no other reason than witnessing this miraculous mechanical pepper-grinder crank out the answers feels entirely legitimate

First maths only makes sense, at least initially, through the mechanics of our hands. Finger-counting, arranging number blocks, sliding counters on an abacus, sliding rules and, of course, calibrating a Curta all share a common denominator in which a love of arithmetic begins not in the abstract world of pencil and paper (or even more abstract on a calculator) but in the sensual world of touch and feel. This grounds the subject in reality before it wanders off, inevitably, into algebraic abstraction.

Second is narrative context. The Curta comes with its own built-in human-interest story of heroism courage, determination and genius. Chances are Herzstark would have ended up being a victim of the Holocaust like so many other millions of Jews were it not for the Nazi’s fascination with his designs for a highly portable, easy-to-use, superfast manual mechanical calculating machine. The story of how Herzstack lost and then regained his Curta patents and eventually benefitted from its commercialisation is no less extraordinary.

Writing our latest Science & Engineering Wallbook has convinced me that every major maths topic in the curriculum from reception to Further Maths A level has, somewhere, a grounding narrative context that can be used as a mental anchor to make even the most abstract concept accessible even to the most innumerate of minds. From Brahmagupta and the number zero and Descartes’ coordinates to the obsessive gambling of Cardano and Einstein’s extraordinary E=mc2 – there is no shortage of wonderful moments along a historical numberline that would, I am convinced, transform young people’s enjoyment of maths and measurement.

And while we are at it, why not give this new approach to maths teaching a name – let’s call it Curtanomics – in memory of that great man with his ingenious arithmetical pepper-grinder that has launched at least one middle-aged innumerate into a new relationship with numbers.

May 4, 2013

Let there be light!

But what kind? That is the question….. A personal theory – which has been quietly fermenting in my mind for some time – receives its first public airing thanks to a recent meeting I had with an old friend who is also the managing director of a famous publishing house.

But what kind? That is the question….. A personal theory – which has been quietly fermenting in my mind for some time – receives its first public airing thanks to a recent meeting I had with an old friend who is also the managing director of a famous publishing house.

He told me that 90% of all ebooks are sold in the UK are sales on the Amazon Kindle platform.

Perhaps that’s no big surprise. The Kindle was first major e-reader on the market and Amazon is the category-killer online bookstore.

But I suspect there is more to it than that. Much more. Most surprising is that people do not generally read books on iPADS or other devices with backlit screens. Why? Because the Kindle is different. Until the HD Fire (big mistake on Amazon’s part, in my view) the Kindle has relied on reflected not emitted light.

The difference is hard to overstate. When you read a traditional paper book the light that enters your eyes is natural and reflected off the page. When you stare at a backlit screen, the information you receive is artificially produced and emitted like a beam of fire into the back of your retinae.

Wander through an art gallery and the pictures inspire you because their colours filter white light and reflect back into your eyes creating an image which, very often, provokes feelings of empathy in the brain. Empathy is triggered, I suspect, by reflected not emitted light.

Let’s zoom out for a moment. For millions of years our brains have been hard-wired to respond to reflected light – from an awe-inspiring view from a mountaintop to the sparkle of a diamond ring. We do not look directly at the Sun – we cannot because it scorches our eyes. Instead we have evolved to learn through reflections, colours, shadows, hues and haze.

This is still true to life today for those seeking inspiration. People do not think to embark on a mountain hike through the convenience of a virtual reality helmet any more than it is fashionable to wear an engagement ring that sparkles thanks to a series of embedded light emitting diodes. The idea is ridiculous because our brains do not respond to emitted light in the same way that they respond to natural reflected light.

We do not look directly at the Sun – we cannot because it scorches our eyes

It explains why iPADs are lousy as book reading devices, despite all the hype when they were launched that they would replace the Amazon Kindle. It explains why the Kindle has been such an astonishing success. I can read a Kindle without it blasting my eyes with LED radiation. It doesn’t tire them. I find the words inspiring – intriguing – I am curious – Why? Because they are reflected not emitted into my mind – just in the same way the National Portrait Gallery hasn’t yet (as far as I am aware) mounted an exhibition on backlight LED screens instead of paint or photographs on canvass or paper.

I suspect the same logic runs through why people are happy to pay for content they receive on paper but unhappy to pay for the same content displayed on a screen.

The psychological difference being the way that light is delivered matters even more because people who consume everything through a backlit screen are, I suspect, being spiritually starved. The problem of too much Facebook, Twitter, computers and TV screens isn’t that addition to news feeds, stock prices, instant messages and tweets is undesirable in itself – addictions of all kinds are and have always been part of the human condition.

The problem is that today our brains are being force-fed data by a blast of manufactured light delivered in a way that appeals to the focused left-hemisphere only, while the right hemisphere – the one which appreciates the big picture – the shadows and reflections of everyday living – is sidelined almost to extinction. The right side of the brain - spiritual, emotional, holistic, empathic self – is being starved by the tyranny of yesterday’s CRT superseded by an LED and backlit LCD revolution.

So next time you wonder what is it about modern living that leaves you feeling empty, cold and undernourished – then simply try switching off the screen and bathe yourself instead in the right kind of light.

So please excuse me, if I now take my own advice.

Very best!

April 19, 2013

Why bad news sells

WHO SHOULD come charging forward into the central reservation of my mental superhighway this week than good old William Shakespeare. Next year it is the 450th anniversary of his birth – and to mark the occasion the august Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, who run the UK’s Shakespeare assets in Stratford-upon-Avon – most notably his birthplace and museum – have set up an initiative for UK schools to honour our national hero every year with a Shakespeare Week.

Tuesday this week saw the official launch of Shakespeare Week (which actually starts next year – so we now have a year to prepare!). The ambitious plan was unveiled at a reception near the House of Commons in Westminster for Shakespeare Week partners – a pot-pourri of educational, publishing, dramatic and curatorial organisations. What on Earth Publishing, my little baby, is a proud partner of the initiative since, in collaboration with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, we are about to start work on hand-crafting a giant 2.3m long Wallbook featuring the 100 most dramatic moments across all 37 of Shakespeare’s plays on a timeline – fully illustrated by Wallbook wonderman Andy Forshaw. It will be published in time for Shakespeare’s birthday week next Spring. I promise!

Top of the bill at the reception was a speech to be given by none other that our very own living educational bard, Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Education.

Never having met the man, I was mildly interested in him having a chance to speak for himself in person rather than for my views on his so-called reforms being shaped entirely by second-hand sources.

But two minutes after he was due to speak, an apologetic minion announced that the great man – even though he was only 5 minutes walking distance away and even though the date must have been in his dairy for months – sadly couldn’t make it.

An unexpected surge of relief rushed through me – not because I no longer had to suffer his speech – but because his cancellation made me feel so infinitely grateful that my job – unlike his – is not one where generally, at every turn, I am letting people down.

Needless to say we had a splendid time without him – many creative minds all pouring out their juices on what can be done to engage young minds in the national treasure that is Shakespeare – the bard who articulated so beautifully the full panoply of human nature from A-Z in his wonderful spectrum of plays ranging from Comedy and History to Tragedy.

I have been musing since Tuesday – on and off – on what it is that Shakespeare’s works can teach us about ourselves today. I have reached one rather unexpected conclusion. He has helped me to understand – which is quite significant for me as a one-time journalist – why bad news sells.

Flick through the newspapers, switch on the TV – turn up the volume on your DAB radio set – and I guarantee that if you had to classify all the news stories you read, see or hear than at least 95% could only be said to be BAD. Go on, try out this morning. I assure you, it is true.

In fact you’ll need no assurance because instinctively we all know that it’s true! We are a culture addicted to BAD NEWS – me, you - all of us are – but why? Ironically, so my Shakespearean thoughts of the week inform me, it’s because modern Western society has become addicted not to tragedy but to comedy.

Just think about it. Today’s Hollywoodisation (horrible word, I know, but somehow appropriate) of storytelling means that it is almost impossible to create a commercially successful story – in film, in a book or on TV – without it being what Shakespeare would call a comedy – you know, something that ultimately has a happy ending. How many mainstream films can you think of that have a truly tragic ending – Romeo and Juliet-like – without even a surviving dog popping its nose out of the wreckage? (The surviving pet scenario is a perfect, and essential, device for flipping Hollywood’s gliztiest global disaster movies from Shakespearean tragedy to modern farce).

Today’s mainstream media cannot stand true tragedy – King Lear-style. We are far too squeamish. How could film-makers possibly sell stories that leave people feeling worse off when they leave the cinema than when they went in? Paying for ‘content’ means giving ‘value’ be it a sense of escapism, an illusion – or virtual reality – where things are better than they really are. If not, then why bother going in the first place? Who these days is going to pay for something that makes them feel more miserable?

Today’s mainstream media cannot stand true tragedy – King Lear-style. We are far too squeamish.

But if tragedy is such anathema in our post-Shakespearean age, then why are our newspapers, TV and radio news programmes so damn full of it?

Thanks to the bard, now I see that of course one person’s tragedy is another person’s comedy. As long as I can read about someone else being more hard up, more miserable, more hungry, less happy, more screwed up than me then, of course, I will feel better. It’s not deliberate or sadistic – it’s just a natural human (mammalian?) instinct that imprints on us a perspective in which we become the comic pieces of a puzzle that turns a bad news story into something that feels good. I – the reader, the viewer, the listener who is not suffering in the same way – becomes the pup poking its nose up out of the rubble.

Like boredom, I suspect our apparent lack of stomach for what Shakespeare called tragedy is a mostly modern disease. We are so used to our feel-good fix that we can’t resist flicking onto the news – to get our Daily Blast of other people’s bad tidings in order to trigger that happy sense of relief deep inside us which courses through our veins each morning – along with the caffeine – giving us the energy, the confidence and the drive to face another day. Our daily Sense of Purpose is built on the backs of all those poor sods everywhere else who make it into the grim headlines.

Like boredom, I suspect our apparent lack of stomach for what Shakespeare called tragedy is a mostly modern disease.

Did bad news sell in the same way in Shakespeare’s England, I wonder?

I suspect not. For a start, people back then didn’t have newspapers, radio or TV (or coffee, for that matter – not quite). What’s more, the vast range of Shakespeare’s extraordinary dramatic output suggests to me they had a wider outlook than we have today. People were certainly less squeamish, they must have had a broader emotional appetite, a less narrow everyday perspective – at least that’s what Shakespeare’s plays suggest to me, which is something powerful, I believe, they also say about us.

A less narrow everyday perspective – hmmm. What a bizarre irony for a modern world that prides itself on global communications and 24 by 7 news! And as for my feelings of relief when Mr Gove didn’t make it to the Shakespeare Week launch? Ahhh – now I understand why I felt so good…..

March 2, 2013

Happy Birthday Christo!

TODAY is the birthday of my late great uncle Christo. He died seven years ago – but he lived to a decent age – 84 – not bad for a boy!

Christopher Lloyd is best remembered for his books on gardening, his column in Country Life magazine and his house and gardens at Great Dixter in East Sussex. It’s a jewel of a place – now under the stewardship of a Charitable Trust that seems to have broken most of its links with the family. I don’t really understand why. It seems that great rift valleys aren’t restricted to tectonic forces that rip apart continents. They are just as common in families. How closely human culture echoes natural forces that have played out over aeons.

Shortly after he died I wrote Christo a letter. I was very close to him – although I was only one amongst many people who were very close to him… Nevertheless, he inspired me in more ways that I can describe. Not a day passes by without his influence scattering itself all around me.

I gave a lecture on Tuesday evening this week – it was at the Daiwa Foundation in London – and, quite unplanned, there he was, popping up again! This time it was to do with his love of peas (which, of course, he grew himself, eating only a few at a time but with the greatest pleasure when they were in season).

The talk at Daiwa was to do with whether or not the trauma of Fukushima will provoke the Japanese people into thinking bigger about their future. Perhaps, I suggested, the experience might usher in a new industrial age that has a more sustainable, longterm relationship with nature than conventional fossil-fuel Capitalism. If the Japanese could develop a template for a low-carbon third industrial age and then export their expertise worldwide, perhaps grounds for optimism about the future of planet, life and people may yet emerge! You can hear the talk here. Christo’s peas popped up during question time at the end…

I digress. I would like to share with you the letter I wrote to him after he died. It now forms part of a book of memories called Dear Christo written by people who knew him well. By the end I was in tears. Bravo to you Christo – and happy 91st birthday!

Dear Christo,

I’m such a lousy correspondent – it’s been ages since I wrote. Not that you have been out of my mind for a day since we last spoke. Let me see, it’s been nearly three years – it feels like a lifetime.

I can picture you now in front of the roaring fire in the Solar. What might you be doing – writing letters on your old piece of board? Or, perhaps, like me, you’re tapping away in front of a screen – not on a fancy new Apple Mac like mine, but on that antiquated laptop running MS DOS WordPerfect – the one that I had as a journalist on The Sunday Times. Do you remember? I tried to pass it onto you for nothing, but it ended up with us having a wrestling match in the parlour because you insisted on giving me £100 for it in cash. In the end I had to submit. Hand-to-hand combat with my dear Great Uncle, forty years my superior, eventually got the better of me.

Now – let’s see. It’s 7.45 in the morning. By now you’ll have walked the dogs, made and baked at least one loaf of bread (by the way, have you finished all that 1940s MacDougell’s flour you found in the cellar yet?) and you’ll have prepared tonight’s steamed pudding for all those guests due to arrive about 6pm. Just the 10 to stay this weekend, I suppose. Standard Dixter fare.

The first time I ever came to stay was when I was 16. Someone must have told me (my dear sister Giny, I expect) that you enjoyed whiskey. So when I approached the large, imposing Dixter front door, not without a little trepidation, I felt fairly sure that at least I would hit the spot with the large bottle of Scotch I was clutching in my left hand.

But when I presented the bottle of Glenfiddich, with hopeful triumph as you opened the door, your face momentarily fell.

“Ugh! – you keep it,” you said dismissively, pushing back my out-stretched arm…“that stuff’’s like ditchwater….. Come on in, wonderful to see you…….” And so in I went, still clutching the bottle, and was immediately enveloped by a big bear hug and a long loud laugh.

I wonder how many of your guests coming this weekend will know each other? Not too many, I hope! I have so many fond memories of the five weeks I spent with you, Christo, when I was a student. I stayed in the Night Nursery, your old bedroom, helping out Croft with the annual orgy of cutting the grass.

“I want this orchard to look like a desert!” that’s what I remember you telling me, the day I set to work. Surely this was a chance, I thought, to work off a bit of that puppy fat that seemed to have reappeared during my student days.

It wasn’t easy work. Raking up a year’s growth of grass and forking it up on the trailer was quite a big deal for someone with a suburban upbringing like me…..

“Oh Chris, you’re not going to leave us so soon ARE YOU…” you’d say (in that tone of voice which meant that saying ‘No’ was simply not an option) as we headed out of the back kitchen door towards the Horse Pond after lunch each afternoon with the coffee and chocolates. “No, no Christo, of course not…..” I would reply, knowing perfectly well that Croft would have polished off his sandwiches a couple of hours ago, at least.

Ugh! – you keep it,” you said dismissively, pushing back my out-stretched arm…“that stuff’’s like ditchwater…..

Staying as your guest that summer meant all those steam puddings and champagne lunches were bound to take their toll….. It should have come as no surprise that despite five weeks of extreme physical exertion, I had actually put on another stone.

But what an opportunity to meet so many of your friends! I kept count – there were 26 people in all who came during those few weeks – Colin, Kulgin, Ken, Gill, Damian, Alan Roger, Russ (x2), Nick & Vicky, Frank, Pip, Pamela Millburn, Beth…. to name just a few….. Even Paul Mac! I’m not sure I ever told you about my faux pas that night when Paul came for dinner with Linda. I turned to her, looking for a suitable turn of phrase to grease our lines of communication. I innocently asked her if she liked to cook… ? Well, how was I supposed to know she had her own celebrity line of vegetarian ready-meals!

Then Beth and you plotted to get me and Paul together, alone. So there I was, playing the piano in the Parlour to Paul, singing him one of my various home-made songs. What a picture! I have to report that he sat and listened very patiently. I can’t quite remember the outcome, but it wasn’t quite like how I imagine it must feel to be ‘discovered’. I heard nothing from him again – well, at least then I knew that a career in writing, perhaps journalism to start with, was probably for the best.

I remember an amusing chap from New Zealand showed up one evening – I think you’d bumped into him at some garden you had recently visited. Since you rather liked the look of him, you did the obvious thing: you asked if he, and any of his friends, would like to come and stay at Dixter for the weekend.

Neal was quite a wit. He became one of your many ‘Christian’ friends. Quite why so many young Christians seemed to be attracted to you and Dixter was always a bit of a mystery… You must have uncorked their suppressed potential for a bit of extra-curricular free-thinking.

At least then I knew that a career in writing, perhaps journalism to start with, was probably for the best.

Soon after my summertime spent cutting, raking and forking the grass Neal brought a gardening friend of his to come along and meet you. I happened to be staying that weekend and we all had dinner. This time Neal’s friend wasn’t a Christian. He was a mild-mannered Moslem with a beaming smile and loads of teeth. Now I remember you and he got on really well….

I was at Cambridge then – we used to write a lot in those days – somewhere in the loft I have your letters. You confided in me about Ken, your piano teacher at Rugby, and how much he meant to you. In fact, just now Matilda was doing her early morning piano practise on one of the Bosendorfer uprights that Ken bought for you and Oliver Cromwell…. The other one is still in the parlour at Dixter. Wasn’t it wonderful to hear Pip learning how to play on your piano? I can’t believe how quickly he became so proficient, nor why Tulippa always growled so much. You said she hated Bach…. .I reckon the grievance went further.

It’s now 7.45 and you’ll probably be having breakfast and taking a look through the morning the post. Kathleen will have popped in, no doubt, with an update on plans for the day. I’m going to indulge my imagination, just for a moment….

As you chat away, I think I’ll quietly tuck into another bowl of stewed apple and cream (don’t want any to go to waste…..) and then I’ll flick through a few pages of the latest copy of Country Life, pausing at you latest cuttings, In My Garden..

Meanwhile, some steam rises up gently from a pan of water on a portable stove behind your seat (I cant’ quite remember its purpose – was it to keep up humidity levels for the plants, perhaps?). To your left is that bunch of blacking bananas hanging on their own mini-hat stand in a corner on the table next to the toaster….

“Corner….” – now there’s a word that cracks through the barrier of silence that has separated us these last three years.

“Corner – Go on back….BACK….. CORNER, CORNER…..” You’ll be pleased to know, Christo, that since we last spoke we now have our very own dog. I’m not sure how well Flossie would get on with your two (I’m afraid, she’s a bit timid) but she’s been a complete delight for Virginia, Matilda, Verity and me. We’ve acquainted her with certain standard Dixter rituals, such as being smothered in a blanket, although as yet she’s not shown any inclination to lap up the remains of my cup of black coffee. What are we doing wrong?

Well, Christo, it’s probably best I sign off soon. I can’t tell you how hard it has been not hearing from you these last few years. I badly miss our weekends and your fathomless interest in me each time I call – wherever I may be, whatever you suppose….. What’s incredible is that you made us all feel that way. Every one of your friends has their own special relationship with you.

Not a day passes when I don’t think of you – or see you standing humorously under the ‘Duck or Grouse’ sign in the Potting Shed. That picture of you, with your eyes twinkling cheekily and your old shoes all hanging out, is stuck irrepressibly on the wall beside my desk. Now I realise what I have missed most during the chasm of these last three years…. It’s the simple brush of your moustache whenever we kissed hello or hugged and squeezed goodbye.

The last time we had dinner at Dixter, it was just us two. Aaron was expected back later that evening. I cooked us each a steak and you watched on from a nearby chair in the kitchen, issuing clear, simple instructions. You could hardly walk because of the pain in your knees.

At the end of the meal, you took my hand from across the table, looked me in the eye and thanked me for being such a dear friend. Oh, Christo! How many of us cherish those irreplaceably precious moments we all spent in your wonderful house and garden, one giant family connected only and completely by a deep love for you.

I really must go. Your breakfast may be over; but my day must go on.

Here’s one thing I know for sure, even if we can no longer physically speak: you won’t have forgotten to sweep up those rubber bands left over from this morning’s post – I’ve got a whole drawer-full myself at home – we’re all avid collectors now.

Forever missing you,

-chris

I really must go. Your breakfast may be over; but my day must go on

If any of you reading this knew Christo or have been to Great Dixter, or have someone you want to tell me about who is or was your spiritual mentor, then do let me know. Dialogue and diversity are so much more fun than monologues and monocultures – no prizes for guessing who taught me that!

Best wishes!

-chris

December 7, 2012

A Visit to Barber Kato

I AM STANDING in the middle of the road. Traffic lights hang from wires strung across street corners in both directions as far as the eye can see. They flicker from green to orange and red – then they pause, reverse – and repeat. Ad nauseam. Ad infinitum. All day and all night.

I AM STANDING in the middle of the road. Traffic lights hang from wires strung across street corners in both directions as far as the eye can see. They flicker from green to orange and red – then they pause, reverse – and repeat. Ad nauseam. Ad infinitum. All day and all night.

Street lamps line the avenue. They are lit. Surely there must be some signs of life? A bus shelter, adorned with a timetable, looks hopeful. Sometime soon the purpose for which it was built must surely be fulfilled! But there are no busses here.

A battalion of bicycles, there must be at least 200 of them, stands in a shelter next to the derelict railway station at the end of the street. There is no-one is here. They too are homeless, their owners gone.

It feels like I am on the film set of a disaster movie. I pinch myself. I walk back down the street – still in the middle of the road because there is no traffic. I see houses that are not quite like how houses are meant to be. Some have collapsed, some have no windows, all the shops are all shuttered up. I see a wall of what look like bin bags piled up high – but these are not ordinary bags of litter – they made of a much tougher, thicker, silo-like material each one daubed with streaks of white paint – it is a code. I know what it means – eventhough I am in a place where I speak not a word of the native tongue.

It feels like I am on the film set of a disaster movie.

************

ODAKA – – the word means ‘little hill’ in Japanese – is a medium sized town, located about 3km inland from the coast, about 12km away from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station on the eastern coast of Honshi, the largest of the islands of Japan.

At 2.46pm precisely on March 11, 2011 a magnitude 9 earthquake struck 70km away from here, 32 km beneath the sea-bed. The energy released was so powerful that it physically shifted the island 2.4 metres eastwards towards the USA, even jolting the Earth on its axis by up to 25 cm (10 inches).

The tsunami triggered by the quake was like no other that has struck a developed nation in living memory. Approximately one hour after the giant seismic shock, waves over 40 metres high washed over the east coast of Honshu in land as far as 10km in places – a disaster that left more than 20,000 people dead in a matter of minutes. Two days later and a second disaster unfolded as explosions from the nearby nuclear powerplant – unable to cope with the flooding from the tsunami –released a lethal cocktail of radioactivity over a 30-mile wide area.

I have some to see the fallout for myself – 20 months on – in all forms: emotional, financial, radioactive. My guide is Ken Okoshi – a highly respected TV reporter and presenter for NHK Television’s Newswatch 9 current affairs show. Ken, who covered the aftermath of this appalling disaster, comes back every few months with his film crew to see what has changed and how the people are coping ….

“A lot of stuff has been cleared up”, Ken remarks, pensively. “It is emptier than before”.

But still – to my great surprise – I see cars lying upturned, some with their engines ripped out like macabre souvenirs from the raw power of nature that struck this place 20 months ago.

Ken shows me what looks like a vast expanse of empty, ploughed up fields – they look innocent enough, ready perhaps for sewing next year’s crops? But this is all new – it is all that remains of what were once densely populated urban districts thick with houses, streets and cars. In an instant this world was usurped by the crushing, indiscriminating force of nature and morphed into a mangled stew of concrete, twisted metal, sticks, stones, bones and mud.

“I met a man looking for his mother’ Ken tells me “ He was just here”, says Ken pointing to a spot on the ground. “When he said he was looking for his mother he didn’t mean her – he knew she was dead – he just wanted to find something, anything that belonged to her – a picture, a piece of jewellery – anything. But the man was utterly lost – he had no idea where his mother’s house was. It was impossible to tell. There was nothing I could say. I was truly lost for words”.

Nothing can be built here. At least not for now. The land is too contaminated. Piles of rubbish, some heaped with mattresses, line what were once residential roads but are now empty tracks – the sort a developer might mark out on a giant construction site before work really begins. I see a huge stack of what look like broken tomb-stones next to a tiny Shinto shrine, the only new building for miles around. Its message made more poignant by the smallness of its imprint in what has become a vast, empty wasteland.

Nothing can be built here. At least not for now. The land is too contaminated. Piles of rubbish, some heaped with mattresses, line what were once residential roads but are now empty tracks – the sort a developer might mark out on a giant construction site before work really begins. I see a huge stack of what look like broken tomb-stones next to a tiny Shinto shrine, the only new building for miles around. Its message made more poignant by the smallness of its imprint in what has become a vast, empty wasteland.

*********

*********

KEN HAS SOMEONE he wants me to meet.

“Yes there is someone working there in Odaka – his name is Mr Kato – he’s the town barber.”

Barber Kato, as he is known, is the first and only person In Odaka to return to his house and his job. Six months ago the Japanese authorities lifted restrictions for people living outside a 10km exclusion zone of the nuclear plant so they could return to their homes – not to live there, just to collect things and to start to clean things up.

But Kato went far beyond what anyone else dared do. He re-opened his barber shop.

Words cannot describe how extraordinary it feels to walk from the utter stillness and loneliness of that a deserted, surreal streetscene – with its working traffic lights and piles of sinister black bags – into the warmth of Barber Kato’s hair salon – which he runs with his wife – for the benefit of a town with no-one else living there.

“When I re-opened the shop….” Kato – a small man with a big broad smile – speaks to me through an interpreter“….of course no-one really came to have their haircut. But when people began to hear that I was open they dropped by instead for a cup of tea.”

“When I re-opened the shop….” Kato – a small man with a big broad smile – speaks to me through an interpreter“….of course no-one really came to have their haircut. But when people began to hear that I was open they dropped by instead for a cup of tea.”

Mrs Kato brings over a steaming bowl of hot green tea – served with another wide, beaming smile.

“Now several months on, people come from as far 50km away to have tea – and sometimes even to have their hair cut – as a show of support for this town and the beginning of the revival of our community”

I find it extraordinary to think that it is over cups of tea that this devastated corner of the world should begin its awesome task of rebirth and renewal – but of course, what else, dear!

On the floor, behind his three swivel chairs, Kato shows me as many 12 large plastic water containers. The tea, I discover, is made with water that Mr and Mrs Kato have to bring by hand into the shop everyday.

‘We have electricity, that came on several months ago, but there is no running water. So we cannot live here.”

The Kato’s are commuters – the come everyday – from the cramped refugee camp-like accommodation built to house people displaced by the catastrophe of 3/11 to their barber shop-cum-café, the only sign of life on the high street in Odaka.

I find it extraordinary to think that it is over cups of tea that this devastated corner of the world should begin its awesome task of rebirth and renewal

The experience of opening up has transformed their lives – and reinvigorated their relationship.

‘It is like we have got married again – like we are on a honeymoon!, says the beaming Kato – “because what is happening here is the beginning of the rebirth of our town!”

Kato’s face lights up as he speak – his sense of hope – his spirit – is utterly infectious.

“And now I realise the importance of ordinary things like water, and electricity – things I took completely for granted before the disaster are now the most special things in the world. I will never waste anything ever again!

As he speaks, Mrs Kato smiles: “And now I always now turn off the tap as I am brushing my teeth – I never used to do that – but now I cannot bring myself to waste a drop!”

Ken, who is sitting beside me sipping tea, asks what Mr Kato now thinks of nuclear power. Should it be phased out altogether? His question frames a huge debate that has been raging across all Japan for the last 20 months and features largely in parliamentary elections due in two weeks time.

“I think in future we must consider the ultimate consequences of what we do, not just about building things for the sake of building them”

Kato’s words strike a chord. I think what an appalling track record human civilisations have when it comes to thinking about the possible longterm consequences of their actions. On the other hand, I have to remind myself that despite 3 million years of evolution, nature never equipped us or our ancestors with the power of foresight – why should it? – we are hardwired to think only in the here and now– enough wit simply to sink or swim as individuals or communities in the wild.

I reach down to my bag, next to the sofa on which I am sitting, and present Kato with a copy of the Japanese edition of What on Earth Happened?

After the tsunami struck I felt obliged to update the book to include the events of 3/11. I explain that by combing all natural and human history into one 13.7 billion year narrative, I see that human history has little to do with what people have done to nature, but everything to do with how nature has shaped people.

After the tsunami struck I felt obliged to update the book to include the events of 3/11. I explain that by combing all natural and human history into one 13.7 billion year narrative, I see that human history has little to do with what people have done to nature, but everything to do with how nature has shaped people.

I have to remind myself that despite 3 million years of evolution, nature never equipped us or our ancestors with the power of foresight

I explain to him that for me the events of 3/11 stand as one of the most significant moments in the relationship between humans and nature in the last 100 years…. alongside the sinking of the Titanic, and the witnessing of earthrise by astronauts on the moon.

I sign a message in the book – something along the lines of hoping in some small way it may inspire him like the big way he is inspiring so many people in and around his community by having the courage to open his shop.

Barber Kato thanks me in the way only he knows best – he ushers me to one of his swivel seats and offers to wash my hair. He fetches water from one of the containers – he boils the kettle to make the temperature just right. He proudly shows me a device he has built himself to pump water from the container through a shower-head into the sink. And, like a modern day Mary Magdelaine, humbly he scrubs.

As he touches my head – massaging it with professional vigour – I feel a surge of invigorating refreshment. Barber Kato is alive! Barber Kato is doing what he loves to do! Barber Kato is doing what he does best!

And so we talk about how barbers have changed the world. There’s Richard Arkwrite, I suggest, the barber from Bolton who invented the water-powered loom that helped to trigger the industrial revolution in Britain. Now it’s his turn. He tells me it was the French who pioneered the idea of a barber’s shop as a place for people to be healed and refreshed. That’s why outside his shop – and outside all barber shops in Japan – there is a large tube containing a red, white and blue bandage that rotates as signal that the shop is open.

**********

KEN TAKES ME to the edge of the 10km exclusion zone around the nuclear plant. The feeling of that disaster movie film set returns – there are no cars – just a huddle of policemen with large orange batons and gleaming white suits wearing safety masks across their faces. Cones, flashing lights and warning signs line the deserted highway.

He asks me what are my impressions of this place? What thoughts are running through my mind?

He asks me what are my impressions of this place? What thoughts are running through my mind?

I say that I am struck by the people that have been uprooted by this tragedy – ripped from the connection with the land they belong to and which, they thought, belonged to them. But then my thoughts turn. They are tempered by the sight of nature all around – and it strikes me how pathetically artificial is the barrier infront of me.

The wild boar – which Mrs Kato told me freely roam the streets of Odaka in nonchalant disregard for any humans they see – are not excluded. They come and go as they please through the undergrowth. The birds, the pollen grains, the spores – none of them care or know what has happened here. Nature is not disturbed. I wonder, perhaps, if it is quietly celebrating, savouring a rare moment of calm ….?

“And what do you think of the Katos?”

This is Ken’s final question before a taxi has to speed him back to Tokyo for his 9 ‘o clock news programme that goes out each weekday night.

The image of what looks like a dead body enters my mind – perhaps it’s a road-crash victim? In my mind’s eye I approach and pick up the person’s arm to look for the slightest sign of life.

“They are like a pulse,” I say, “a sign that there is life after death for the people and the community of Odaka.

Nature is not disturbed. I wonder, perhaps, if it is quietly celebrating, savouring a rare moment of calm ….?

*******************

JOURNEYING BACK from the coast to the city of Fukushima takes 2 hours. From there it is another 90 minutes by Bullet train back to Tokyo. Ken has gone so now I talk to Kyoko – Ken’s executive producer.

She tells me that for a while it seemed like the whole of Japan united behind the victims of 3/11 – that life in Japan could not possibly ever be the same again. Nuclear power had to go – people had to find a new way of living more in sympathy with nature. But now, she says 20 months on and it seems more and more like business as usual. Perhaps the disaster is beginning to recede from people’s minds?

I realise now why Ken brought me here in the first place. He wants the Japanese people not to forget. He wants what Kato wants – people to think with foresight about the long-term consequences of what they are doing.

I look at Kyoko, recalling how Japan has reinvented itself twice in the last 150 years. Surely now is the time for Japan to reinvent itself again? And to revive its flagging economy perhaps with the design, manufacture and export of a new generation of technology and expertise needed for a more robust society in future…. ?

I pontificate.

“Just think: if every roof in Japan had a solar panel fitted, and if every person in Japan could harvest their own energy then people we would not waste it. Just like Barber Kato who cannot bring himself to waste a drop of water now that he has to carry it everyday from his home to work. Or like Mrs Kato’s new habit of switching off the tap while she is brushing her teeth!”

Kyoko looks away.

“I hope, I wish – I think we all wish……I think that’s what most Japanese people want…

A deep sense of irony descends on me as we arrive in the bustling metropolis of Fukushima. Our ability as a species to rally around a long-term vision seems only to last fleetingly – and usually in the wake of appalling tragedies such as 3/11 – but then it decays, inevitably I suppose, like the radioactivity on the fields, houses and the coastline we have just left behind.