Christopher Lloyd's Blog

December 3, 2021

It’s Up To Us: A Children’s Terra Carta for Nature, People and Planet

Join His Royal Highness, world history author Christopher Lloyd, and a group of 33 prominent illustrators from around the world in this moving exploration of the wonders of Nature, the threats our Planet faces and what we People can do to build a brighter future for all.

Christopher Lloyd introduces our series of interviews, where each illustrator explains the inspiration behind their artwork, what it means to be involved in this unique project and offers advice to aspiring young illustrators.

Watch the YouTube illustrator video series here https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLzDNXmNneXswFji_6cfrAOEItLV31B5Dc

Resources:

Check out our free engaging activities available on The Prince’s Foundation website https://princes-foundation.org/education/its-up-to-us

Reviews:

“A triumph, both in terms of the poetically rendered text, and the emotional impact of the hugely contrasting illustration styles on display.” – Caroline Sanderson, The Bookseller

“It’s Up to Us is entirely focused on climate change and the most pressing environmental issues currently experienced by the Earth.” – Alice Scarsi, Daily Express

“[It’s Up to Us] helps the next generation understand the importance of putting nature first.” – Victoria Murphy, Town and Country Magazine

May 23, 2017

What on Earth? Books wins an International Book Award!

Sorry, this entry is only available in American English.

September 28, 2014

The Corporate Callosum

TIME for a quick trip down memory lane. Today I have an article published in The Sunday Times, my journalistic alma mater, and it’s been at least 10 years since I have written a piece for them. The occasion is to mark 50 years of the launch of the Sunday Times Business News section. I was asked, as former Technology Correspondent, to write a piece of the top ten technologies that have most changed the world in the last 50 years.

Well, – I did my bit. But the problem with writing for newspapers is the annoying reality that they usually only commission you to write what they want their readers to read. Sometimes you can break through with a new idea, but generally it’s a world where section editors are second-guessing the prejudices and appetites of editors, whose minds are focused on what will sell and what their proprietors might like to see in print. At least, that’s how it was and I suspect still is.

The business piece that I would really have liked to have written has nothing to do with technology that has changed the world. Rather, it is to do with the fascinating parallels I keep finding between what makes a successful person and a successful business.

Of course, defining a successful person is a matter of great subjective debate. It is not, to my mind, about how much money they earn, or if they have a title or some other decoration. Nor is it to do with ‘good works’, as such. Rather, it is the extent to which they are able to learn and adapt and then communicate their learning and adaptations to others in useful, inspiring and meaningful ways, since, as we all know, the only constant anyone can be sure of is…. change. With that benchmark in mind, the organ of most importance is, naturally, the human brain.

The only constant anyone can be sure of is…. change.

So what happens if we try to take a model of the most functional – successful – human brain and see to what extent it maps that onto successful business organisations. Well, that’s what I just tried to do on my walk in the Kent countryside with Flossie the dog just now, and the conclusion we reached was rather intriguing.

I took as my successful business, the one I knew so well all those years ago when I was writing regularly for The Sunday Times – News Corporation.

I actually even got know Rupert Murdoch a little bit in those years. One hysterical and highly memorable episode was being flown from London to San Gimgnano, in Italy, on the News Corp corporate jet.

Rupert had taken a huge villa there and was holding court with all his senior executives for a month - a working honeymoon (his third, so far). I was one half of a two-person team tasked with presenting a business plan for a new online venture. We spent an hour or so talking it through, sitting next to Rupert on a sofa in the summerhouse by the swimming pool. He seemed to like it. Rather, he seemed to like us, which is how most of his decisions were made. So, after a quick call to the Newscorp finance director, Dave Devoe, we got our funding, as requested – a cool £17m.

We spent an hour or so talking it through, sitting next to Rupert on a sofa in the summerhouse by the swimming pool.

So, I am thinking, how is it that Newscorp has grown into one of the most successful businesses in the world? Of course, the phone hacking scandal has taken the sheen off the business recently (bizarrely, Andy Coulson was drafted into alongside myself and another to help run the new online venture long before he became editor of the News of the World or David Cameron’s media advisor). But still, it’s about 50 years since Rupert Murdoch bought The Times and The Sunday Times – and in that time this legendary media mogul has built a stunningly successful global media enterprise – the perfect subject, you would have thought, for scrutiny in the newspaper’s 50-year anniversary celebrations today…

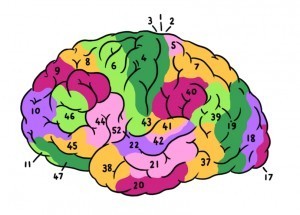

At the risk of grotesque over simplification, a good functioning brain, well adapted for survival in a changing dynamic natural environment, seems to use two different but complimentary operating modes – one to focus on the crucial near-term issues of feeding and breeding (left hemisphere) leaving the other (right hemisphere) to keep a look out for changes in the environment – such as the shadow of an impending predator (see Wallbook Weekly, The Divided Brain).

What I now realise is that Rupert Murdoch’s corporate structure for News Corp almost exactly mirrors this dual operating dynamic.

The newspapers were traditionally cash-cows, tightly managed and focused (left hemisphere) on generating huge levels of income. This money was then removed from these cash-generative operating businesses and passed to a central business development function based in New York. These were the guys on the look out (right hemisphere) – judging how the business environment was changing and seeing how its cash reserves could be invested in future businesses that would potentially compete, or one day replace, the traditional businesses of delivering daily news on paper.

News Corp’s right hemisphere masterstroke was to invest the newspaper’s money in Sky TV – a decision the newspapers would never have made themselves, so obsessed were they in their own world of print, ink and paper.

So my suggestion is that News Corp’s dual processing system for dealing with a dynamic, changing business’ world is based (unwittingly I am sure) on the very same model that nature has evolved to maximize the chances of individual survival in the wild.

Critically, connecting these two hemispheres is a thin band of tissue known as the corpus callosum – and that’s where Rupert and his phone calls to the financial director, come in. Rupert himself was the connective tissue between two warring hemispheres. That was / is his leadership genius. One side generating cash, the other taking it and spending it on new ventures some of which thrive and some of which perish in the dynamic, always changing business world.

Of course how News Corp will fare when, as eventually must happen, its founder and leader departs this life, who knows? A brain without the connective corpus callosum has severe limitations, although it can still function. Nevertheless, a study of Rupert Murdoch, as a kind of Corporate Callosum, just further underpins my suspicion that businesses – and business leaders – would do well to get out of the boardroom and into the wild to study the well-honed survival strategies of Mother Nature.

August 19, 2014

A Hunch Over Lunch

I HAVE BECOME almost obsessively fascinated by the process of learning. I guess it stems from giving lectures, visiting schools, writing books that try to explain big subjects – speaking with teachers – having my own kids – living with my own thoughts! It means, of course, that whenever I have time to read I almost always immerse myself in books about the human brain. How utterly futile is fiction when the most fascinating narrative of all is to try to discover the machinations of what is going on – one moment to the next – inside my very own head!

And so, as I camp out on the banks of the river Rhine whilst my younger daughter plays in her Marimba music course about 15 minutes downstream, I am taking what time I have between projects, proposals, emails and admin, to deepen my understanding of this lump of white-grey lard inside my skull.

I have discovered two books that are completely changing my view of – well, just about everything. The first is out of print. It’s a bizarre but brilliant fusion of psychology and big history written by a now defunct psychology professor called Julian Jaynes entitled: “The Origin of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind” (1976). Anyone with an interest in neurology, history, ancient civilisation, schizophrenia or hypnosis MUST read this book. You don’t have to accept his theory, but just let his ideas play in your mind – as they have in mine – and then see how they fare.

The second (by the way, I really recommend reading Jaynes first) is by Cornish author Tony Wright and agriculturalist Graham Glynn called Return to the Brain of Eden (I believe it was first published in 2008 under the title Left in the Dark). I finished it yesterday over lunch.

I shan’t go into the theories of either book – that’s for you to discover if you have sufficient curiosity to take my word for it that you will NOT be disappointed!

How utterly futile is fiction when the most fascinating narrative of all is to try to discover the machinations of what is going on – one moment to the next – inside my very own head!

However, reading them both back-to-back has led to tsunami of synaptic syncopation between my own left and right hemispheres. What this thought-showers seems to have produced is a bizarre, but intriguing explanation for the dramatic rise of autism in western culture.

Let me explain.

Dominance of the left hemisphere over the right, in all our brains, is, according both Jaynes and Wright/Glynn, a product of hormonal balance and imbalance. In short, it is the prevalence of testosterone during feotal development that has, over the course of the last 1 million years of human evolution, contributed to the dominance of the left brain hemisphere over the right.

In boys, where testosterone is produced more bountifully (since it is the masculine-making hormone), the dominance of the left hemisphere can become especially pronounced. Perhaps that’s why (until this month – at last!) every single winner of the Fields Medal maths prize since its inception in 1936 has been male. Right hemisphere capacities – which involve social interaction, empathy, emotional intelligence and humour – are especially suppressed in people with ‘over masculine’ brains. Today we say such people suffer from autism. Reinforcing the narrative is the fact that by far the majority of statemented autistic young people today are boys not girls – on average the ratio is about 4:1.

Masses of research is being targeted at trying to find a cause, but so far there are no clear answers. Is it genetic? environmental? immunization? hormonal? dietary? cultural? Maybe it’s a just a myth! Apparent emergence may simply be because we now have a label and pots of people over-eager with diagnosis…

But as anyone who has an autistic child, or who teaches one, will know, these are very special people, most often with very special needs.

So now I am going to reveal the thread of connective tissue in my own corpus callosum that is germinating, at least for me, a new theory (I cannot find it articulated anywhere else) as to why the incidence of autism seems to be rising so steeply in our modern age.

It’s all to do with screens.

A stunning statistic was revealed in a survey by OFCOM earlier this month which revealed that British people now spend more time staring at screens than they do sleeping (see http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-28685572).

Of course, there is no link to autism in this story – but hear me through.

And the problem, by the way, has nothing to do with children – or autistic children in particular – playing too many computer games or spending all their time watching TV or surfing the net.

Rather, it’s their mums.

When you look at a computer screen – especially if viewing occurs within two hours before the body is naturally ready to shut down and go to sleep – the violent bursts of blue light (frequency 460 – 480nm) emitted from modern LCD screens are known dramatically to inhibit the secretion of the hormone melatonin by the pineal gland in the brain. This is an established fact.

The problem, by the way, has nothing to do with children – or autistic children in particular – playing too many computer games or spending all their time watching TV or surfing the net.

And melatonin, so I read, is the key hormonal suppressant for testosterone in the body. According to Wright and Glynn, it is a balance between melatonin Vs testosterone levels that will largely dictate the way in which the embryonic brain develops in a mother’s womb. Too little melatonin and runaway levels of testosterone will most likely trigger an exaggerated masculinity of the growing foetal brain. A lack of melatonin therefore sounds to me like immersing the emerging left-hemisphere of an embryonic male brain in a bath of testosterone-laden miraclegrow.

And so I put it out there. Perhaps pregnant mums staring at screens – particularly in the two hours before their bodies would naturally go to sleep – best accounts for rising levels of autism in modern society. It probably doesn’t matter so much if the baby you are carrying is a girl – but if it’s a boy…..?

Taking folic acid, cutting out alcohol, avoiding drugs – now add this to the list of well established ingredients for having a healthy pregnancy: no TV or online shopping after 7pm…

I’m sorry if it sounds harsh – akin to a kind of discriminatory curfew for those bearing sons and heirs…

It’s just a hunch.

May 27, 2014

The Wright Stuff

Wright Stuff from Christopher Lloyd on Vimeo.

Home Educators, so often pictured by the press as crazies who have slipped off the system, are vigorously defended by world history author Christopher Lloyd in this 11 minute interview for Channel’s 5′s Matthew Wright.

May 8, 2014

The Omnivore’s Dilemma

MICHAEL POLLANS brilliant book of the same title does a noble job of fusing evolutionary biology with everyday life, but actually the issue goes a great deal deeper than a history of the world in four square meals.

MICHAEL POLLANS brilliant book of the same title does a noble job of fusing evolutionary biology with everyday life, but actually the issue goes a great deal deeper than a history of the world in four square meals.

One of the most profound questions you can pose to a class of curious kids is to ask them to list the biggest differences they can think of between humans and other mammals.

It’s a discussion that leads to all kinds of fascinating cross-curricula insights and it works just as well whether the class is year 1 or A-level.

This very question pops into my mind especially at the moment as my younger daughter, Verity, is limbering up to her History GCSE and together we drilling and killing our knowledge of the build to World War II. What were the causes? Was it the failure of the treaty of Versailles? The Great Depression? Hitler’s charisma? Western attempts at appeasement? The failure of the League of Nations?

What frustrates me most about this process is that one of the most fascinating reasons for the break of WW II from a big history perspective never makes it into the history syllabus because, well, history is history and in our current bonkers system of silo-subject-driven education, history is not fused (as it should be) with biology and psychology.

Humans are different from most other mammals in that they eat meat and veg – we are omnivores. Look around you every day and you will see how the omnivorous human habit has created a species with extra-special potential for causing unrivalled havoc.

Some mammals are herbivorous and their social instinct is herd-like – they follow. The want to be led. They are not aggressive on an individual level, they depend for their survival on being in crowds. Sheep and cows are the most obvious, everyday examples although deer provide a better model of this behaviour pre-domestication – fleet of foot but herd like.

Other mammals are carnivorous – aggressive, usually solitary, unless they need to be in a pack to kill. These are the hunters and killers like lions, tigers, wolves, bears – nature has plenty of stereotypes – take you pick. They all eat meat.

Somehow, probably at roughly the same time as upright walking hominids diverged from our closest living genetic relatives, chimpanzees (perhaps 4 million years ago?), our direct ancestors developed the more flexible habit of being able to at veg and / or meat – depending on what was available at the time. Freely available hands helped, I am sure. Flexibility of food preference was surely a survival advantage.

The devastating consequence is that both herbivorous and carnivorous patterns of behaviour have become intertwined in human genes over the last 3 million years. We like to follow, but we also love to kill. Human nature can best be understood as the inextricably interlinked psychology of herbivore and carnivore – creating a unique, lethal cocktail of insatiable followers and megalomaniac leaders.

Human nature can best be understood as the inextricably interlinked psychology of herbivore and carnivore – creating a unique, lethal cocktail of insatiable followers and megalomaniac leaders

The Germans followed Hitler because they had an inner, primeval instinct to be sheep – a mindset driven by peer pressure, which is far from unique to Germany. The desire to follow and be in a large group is a trigger for human satisfaction and fulfillment throughout history. The same phenomenon helps explain our curious desire even today to kill people we have never met for the sake of satisfying a collective faith or national identity. People do it simply because they are driven by the need to conform to the expectations, aspirations, prejudices and beliefs of the group (the herd) to which they identify. It is deeply ingrained.

And then there are the killers – from the charismatic Alexander, Tamerlane and Genghis Khan, to Napoleon, Stalin and, of course Hitler. Mostly they cut a solitary, lonely picture-gallery of individuals hard-wired to lead – in whatever direction gets the best catch. What powers them is the strength of the following they create. It’s a self-perpetuating omnivorous dilemma where our herbivorous instinct to follow feeds our carnivorous instinct to lead – in a never-ending perpetual loop of violence that erupts like a volcano over time as pressure builds and is released.

I so much wanted to discuss all this with Verity on the sofa this morning as we wrestled with the causes of World War II– but I figured my sideways desire to connect the worlds of biology, psychology and history would not score much on the tabulated mark-sheet of that anonymous examiner who will, for a moment, scrutinise her paper.

But what poverty of opportunity, discussion and knowledge emerges from our inability to connect! Never fear. I shall chat it through with Verity – but after the exams are gone – and, of course, it will be over a hearty meal of meat and two veg…

May 5, 2014

Connecting the dots of the past

CURIOSITY is our most precious natural instinct. It is how we learn all the most important life skills from talking to tickling from cradle to grave.

But today knowledge is usually chopped up into separate subjects – into a timetable, a syllabus or curriculum – usually by adults who are addicted to measuring and recording a student’s progress through constant tests and examinations.

All too often, the unforeseen consequences of this modern industrialization of education is to kill off natural curiosity. How can children possibly follow their interests when they are constantly being told what it is they need know? Much better is to challenge them to find out for themselves and become an expert wherever their curiosity leads them… then they can become what nature truly intended – their own self-learning system!

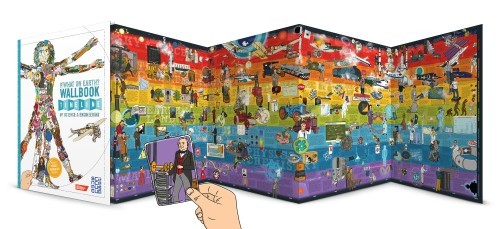

That’s why I wanted to find a way of presenting a big picture to people – young and old alike – so their minds can roam freely and stand back in awe at the most extraordinary story of all – far more incredible than any fantasy or fiction – the story of the Universe and our home, the planet Earth, over 13.7 billion years!

Imagine a book that will be your guide – in pictures and words – where you don’t have to start at the beginning and read to the end following the arbitrary path of an unknown author! No, you can start in the middle or wherever your interests lie and read left, right, up or down – without ever getting lost because of the timeline beneath! This is more what nature intended, because you may go wherever your curiosity leads!

And how about unfolding the book? No need to stuff it on a shelf like other books because you can hang it on a wall or spread it out on a table or a floor so several people can explore it and learn together, spotting things as they go, commenting, discussing, talking, debating…

For me the joy of telling big stories is like the Wallbook itself, it has no beginning and no end. It is just a constant fascination with connecting together the dots of the past, giving them meaning and making them memorable through visualization, context, cause and effect.

If just a little piece of the thrill I get in compiling these puzzles of time into a coherent narrative on a timeline rubs off onto you – be you a parent, a teacher, a child, or – perhaps best of all – just a curious individual – then I will be truly delighted. Do let me know – I would love to hear from you!

March 8, 2014

All The World’s A Stage!

Introducing children a young as five to the complete plays of Shakespeare could be the answer to making our curriculum more human, says Wallbook author Christopher Lloyd

Introducing children a young as five to the complete plays of Shakespeare could be the answer to making our curriculum more human, says Wallbook author Christopher Lloyd

THEY ARE WITH us from the moment we are born (perhaps before?) and stay with us until the day we die. They define us. Most people would agree that without them we are not human. I am referring to feelings. Nothing is more fundamental to our being.

Yet is it remarkable how little science – and education – has to say about them. Since Charles Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals surprisingly little research has been focussed on why and how we feel the way we do. Psychology and neuroscience nibble at the subject from different sides, but since feelings are so hard to describe let alone measure, it is mostly an un-trodden domain. Emotions are not rational. They are “not logical, Captain”, as the infamous Spock would say.

Worst of all, even though emotions generally rule our everyday lives, they hardly feature at all in the school curriculum. Reason – packaged up morsels of maths and physics are today’s hot topics. Literacy – at least initially – is more to do with learning how to read, less about understanding or sharing feelings, while the whole business of examinations and testing is about as unfeeling as can be imagined. Music and drama – those soft, right-hemisphere subjects – are probably the closest our school system gets to the emotional roller-coaster of everyday living, but usually these are subjects relegated to the sidings as optional extras.

What’s to be done? How can sentiment gain a more central place in the curriculum for students of all ages – from as young as five to 18.

One solution is to make it compulsory for every school child to be introduced to the complete plays of William Shakespeare from the age of five, and to ensure that these magnificent plays continue to be on offer to all pupils throughout their school days until the day they leave.

Surprising as this may sound, it is a conclusion I have come to after having had the privilege to work for the last 18 months on a fascinating project in collaboration with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust – a charity established in 1847 and charged with looking after Shakespeare’s heritage. During this time, we have been pioneering a new way of introducing young children (and their teachers and parents) to the emotional power of the complete plays of Britain’s greatest literary hero.

Make it compulsory for every school child to be introduced to the complete plays of William Shakespeare from the age of five

The complete plays of Shakespeare represent an emotional spectrum no less significant than James Maxwell’s electromagnetic spectrum is in the world of science. Everyday all of us, young and old, experience the essence of what is presented in these 38 stories. They are a comprehensive encyclopaedia of feeling – a reflection of our emotional selves that contain every possible colour and hue of human emotion contextualised in the power of narrative drama.

But how on earth can you present the plays of Shakespeare in a meaningful way to children as young as five? Ask any 14-year old who is beginning their studies of Shakespeare’s plays for the first time as part of the English GSCE and the groans are as predictable as they are universal.

In my view, we make three basic mistakes: we begin too late, we rely far too heavily on words and, finally, we only look at fragments, not the whole.

Imagine the challenge of introducing a five-year old child to the complete works of Shakespeare. Where would you begin? Perhaps with a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream with fairies arguing in a wood? Or maybe at a masked ball where two lovers from rival families fall in love at first sight?

Our project, inspired by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Educational Manager, Dr Nick Walton, took exactly the opposite approach. Rather than suggest one play, or a scene of a play, why not show ALL THE PLAYS AT ONCE so that a young mind can do what is does best – roam through any of them using nothing more than the power of natural curiosity?

Of course the plays should be presented in a way they were intended – that’s primarily through images not through words. Afterall, today when you go to a theatre you go to SEE a play, not to HEAR it. We dream in images, we remember in pictures. Our brains are hard-wired to make judgements and feelings based more on how the world looks, less about how it sounds.

Of course the plays should be presented in a way they were intended – that’s primarily through images not through words. Afterall, today when you go to a theatre you go to SEE a play, not to HEAR it. We dream in images, we remember in pictures. Our brains are hard-wired to make judgements and feelings based more on how the world looks, less about how it sounds.

So, for the first time ever, we have assembled all of Shakespeare’s 38 plays on a fold-out timeline showing when each was written and what was happening in Shakespeare’s life and around the world at the time. Each story is set inside an audience box around the stage of the Globe Theatre where his plays were performed from 1599 until the theatre dramatically burned down during a performance of Shakespeare’s last play, Henry VIII, in 1613.

Even on a 2.4m long fold out timeline, there isn’t room in a single audience box to retell each play in its entirety. But the main plot, the characters and most importantly the transformation of emotions in each story (that can translate into feelings that we all experience in our everyday lives) are all possible.

Now it’s up the child (with their parents or teacher, perhaps) to choose where to wander and which plays to look at.

See those ghosts circling around a tent! What’s that? – a bear? A woman falling out of a boat.. ? Witches dancing around a pot….? A boy with a donkey’s head…? a woman struggling with a snake around her neck, she doesn’t look too happy!… Or that fat guy with his head popping out of a laundry basket … what on earth is he doing?

In just one sweep we’ve touched on Richard III, A Winter’s Tale, Pericles, Macbeth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Antony & Cleopatra and the Merry Wives of Windsor.

A woman struggling with a snake around her neck, she doesn’t look too happy!

We could just as easily explore which plays may be based on fact and which are made up. Fairies are fiction, Henry V probably not. Best look him up just in case to see if a king called Henry V actually existed…… Yes he DID – must be fact…..

For example, the emotional journey from joy to hate to sorrow could be the story of a child being given a birthday present, it being seized by the child’s sibling and then destroyed in a struggle by the first child in a vain attempt to get it back. The same emotional rollercoaster could also be applied to the story Julius Caesar. His joyful entry into Rome after a triumphant victory in battle, the hatred stirred up in the hearts of his fellow rulers at Caesar’s rising popularity which could spell doom for the Republic and the sorrow of Brutus and his co-conspirators once the consequences of Caesar’s murder play out. Such transformations could equally be understood in terms of colours – perhaps yellow (joy) to red (hate) and blue (sorrow).

To engage a child in such stories is simply just a matter of approach, not a matter of them not being old enough. If a fourteen year old, who has never before experienced the world of Shakespeare, is compelled to sit in a classroom and take it in turns reading a play composed in a quaint, confusing language, (he probably hates reading anyway) with myriad intricate plots and subplots that were never designed to be read in a book anyway – it is no great surprise that pupil engagement does not naturally follow.

Compare with this a 5 year-old child who realises that the emotional journeys they experience themselves every day are also played out in stories from the plays of Shakespeare which can be brought to life through a galaxy of pictures!

A Wallbook of 38 plays can and should never be a substitute for actually seeing (and hearing) the plays of our greatest playwright in a theatre. But if a child’s curiosity is aroused sufficiently by images that stick in their minds, be the ghosts, fairies or bears, such that they decide at some point that they’d like to see the play for themselves, then the Wallbook’s job is done.

Later this month, more than 2,000 UK primary schools will join in a celebration of Shakespeare Week, (17th to 23rd March), an initiative set up by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust to celebrate the 450th birthday of the bard. What a fabulous opportunity not only to instil a love of Shakespeare at an early age through pictures and feelings, but also to make our school curriculum a little more about emotions and not all about facts, figures and reason.

An edited version of this article appeared in Weekend Telegraph on 8th March 2014

January 27, 2014

Sunny Bonnington

IT IS ONE of the greatest privileges to spend all day with a range of children aged six to 11 and then the evening with their parents and the next day with their teachers in a teacher training workshop. If ever there is an opportunity to have an impact then surely this is it. The child, their parents and their teachers – all three points in the triangle of stakeholders surrounding any curious young mind.

So it was last week at Sutton Bonnington, near Loughborough. A smallish state primary with a wonderfully creative atmosphere. I have discovered a bunch of indicators – like a litmus test – that immediately give a good feel for the culture of a school.

The caretaker ‘Snowy’ provided the first spark of positive energy. How is a caretaker regarded in the pecking order of a school? Snowy was clearly near the top. He was busily polishing the hall floor when I arrived at 7.45 am to set up my giant Wallbook of Natural History. Nothing was too much trouble for Snowy. Every member of staff, including the head, instantly greeted him and vice versa – with conversations leaping up and slapping me in the face all around, like a shoal of flying fish. I knew this school visit was going to be good.

How a culture treats its admin staff stays such a lot. A few years ago I gave a series of talks at schools in Northern Ireland. My librarian hosts had just been categorised in the school accounts by their bureaucratic bosses in the same line as the catering staff (well, there’s no curriculum silo for librarians to reside in). The effect on morale was catastrophic.

Every member of staff, including the head, instantly greeted him and vice versa – with conversations leaping up and slapping me in the face all around, like a shoal of flying fish. I knew this school visit was going to be good.

Outside says a great deal, too. A school that falls into the trap of thinking that learning is predominantly an indoor, classroom pursuit is dysfunctional at best. At sunny Sutton Bonnington there were chickens in the playground and tables marked up with chess, snakes and ladders and nine men’s morris promoting non-physical exercise inside and out. A wall, created by the pupils, was peppered with artwork showing a timeline of events in the last 60 years to celebrate the Queen’s 60th Jubilee.

Best of all was the small wooden amphitheatre with accompanying stage for outdoor oratory. Aristotle didn’t have a peripatetic school of philosophy for nothing. Learning happens most naturally on the move and outdoors – with blood pumping, conversations flowing and the forces of nature full in your face. Not inside, seated behind a desk.

My initial impressions were well founded. Every year group, from reception to year 6, was a model of curiosity, intrigue and courtesy. It almost goes without saying that these pupils general knowledge was superb. Most young people know far more than most teachers and parents realise. In fact my job as a guide through the history of the world, or the story of life on earth, is mostly about identifying which brains in the room know which fragments of knowledge. Then, pretty much all I do is help piece the pieces together with some narrative glue. The story is the room – it was there all the time – scattered in shards within these various heads.

Pretty much all I do is help piece the pieces together with some narrative glue

When a school has the inspiration to organise events for parents in the evening the effect can be even more electrifying. I am convinced that learning reaches a peak resonant frequency when parents, teachers and children are all enjoying an experience together in the same place, at the same time, where they can can share, discuss and interact.

So when David, the University professor, picks a fossil from pocket number 4 he can’t recall what it’s called. But thankfully Fermin, in year 3 – he knows the answer – of course, it’s a trilobite! Just imagine the bolt of dopamine shooting through that young boy’s brain as he announces his correct answer in the face of the hesitating academic. What unforgettable joy!

In the shadow of such a giant narrative – 13.7 billion years – everyone meets on a common level because none of us were given a big picture perspective when we were at school. We are all experts in fragments, at the cost of not having a fit-for-purpose overview. I guess that’s what makes big history so powerful. The hierarchies, the patronising` relationships are gone. We are all students together in the ongoing saga of the story of life on Earth.

November 2, 2013

The Power of Non-Fiction

ENGLAND, WE HAVE A PROBLEM. According to the latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) education report our young adults have amongst the lowest literacy rates of any country in the modern industrialised world. England came 22nd out the 24 countries surveyed.

ENGLAND, WE HAVE A PROBLEM. According to the latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) education report our young adults have amongst the lowest literacy rates of any country in the modern industrialised world. England came 22nd out the 24 countries surveyed.

What is going on? It seems that for at least a generation all significant attempts by government and educationalists to nurture a love of reading amongst younger people appear to have failed.

Recently I was asked to speak at the Federation of Children’s Books Groups annual conference, at Bradfield College near Reading. It is an august organisation dedicated to instilling a love of reading in young people. The gathering, now in its twentieth year, was packed with teachers, book lovers and educationalists.

‘How wonderfully refreshing to have a non-fiction author speaking’ said one delegate after I had given my 60 minutes romp through the history of the world, with a giant Wallbook timeline as a backdrop.

Why, I wondered, should being a ‘non fiction’ author be such a big deal? In my world stories about the real world are so much more amazing than any number of fantasies you can dream up in your mind. If you love truly amazing stories then non-fiction’s the place for you…. Most children I speak to seem to agree.

Facts, how things work, encyclopaedias, maps, explorers, books about nature, superheroes and villains from the past – in my experience this is the stuff that really sets off fireworks in many young brains. World records, bloody wars, space travel, Titanic….. to many youngsters these stories are no less incredible than Harry Potter or Spiderman.

As adults we forget that to the young mind reality is often far more magical than fiction. It’s only as we grow older that social conventions condition us into thinking that the world around us is ‘normal’ – far from it!

Take the birth of a child – it is a stunningly extraordinary occurrence. To any rational mind, the self-assembling mechanics of foetal embryological development utterly defy ordinary comprehension. And just because a new baby is born on average 370,000 times worldwide every day doesn’t make it ‘ordinary’. Frequency should never undermine wonder. In fact, to a curious young mind the more often something amazing happens, the more extraordinary it is!

I recall visiting the Picasso museum in Barcelona with my wife and two young children when we were on our travels in a campervan around Europe. One display board explained how it was this great artist’s adult ambition to learn once again how to paint like a child. I remember how powerfully I was moved by his attempt to rediscover a sense of wonder and curiosity about the everyday world. His paintings now seem to make so much more sense.

For most of us grown-ups the extraordinary world around us has long since become mundane and fascination for fact is often substituted by an addiction to fiction – as is shown by the difference in sales each week between fiction and non-fiction titles.

As I left the talk I gave to the Federation, that woman’s voice kept reverberating around my mind. Why did she say it was such a novelty having a non-fiction author give a talk at a conference on reading and children’s books?

Then a penny dropped. Almost without exception the books that are generally used to promote literacy in schools are popular reading schemes based on a diet of fictional stories, graded into levels that can easily be monitored and measured. Using the same set of books for every child means they can be measured against each other – ideal for an adult-centred approach to assessing performance in schools.

Now put yourself in the mind of a reluctant child who is being taught to read via such a scheme. The question most likely to be going through their mind will be this:

Why on earth are these adult bullies forcing me to learn how to read something that I am not interested in anyway? What’s the point when I want to be outside playing with my friends?

And if the educating adult were being brutally honest, I suspect the answer may well be this:

Because it’s my job. Because I want to help you succeed in life. Because it’s my responsibility to help you pass your tests…..(which means I will be praised by your parents and the head teacher and the school will look good in its league tables….).

But all is not lost.

On Thursday this week schools all over the UK will have the chance to celebrate National Non-Fiction Day, now in its third year – a relatively new initiative organised by the Federation of Children’s Book Groups.

Now imagine a young boy who happens to have a fascination with space travel. His teacher asks him to find a book from the library that he finds interesting. He chooses one about the true story of those astronauts who failed to reach the moon on Apollo 13 and only just managed to return to Earth in what remained of their spaceship after it had exploded.

Now he is taking a book he wants to read because he is following his own natural curiosity about something he is already interested in. And the best way for him to find out more is… to learn how to read.

England – we do not have a problem. We just need to remind ourselves again and again that children learn best through their natural curiosity. When and where they will learn to read doesn’t much matter. Far more important is to ensure we do not diminish their built-in light-bulb of fascination for the world around them by forcing them into senseless reading schemes many of which have little natural context, meaning or purpose to a young spongy mind.

This article appeared in the Weekend Telegraph, p.13 on Saturday 2nd November 2013