Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 4

March 14, 2025

Book Reviews: James, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Is there a hotter book than James by Percival Everett? Sure, the popularity is waning by now, but there’s still no paperback, and we still keep it on the front table in a tall stack at the bookshop because even a year later, James is selling. It’s being read. People are loving it. And the world nods along to 2024’s assessment of it as “book of the year.” If you haven’t read it yet, you are out of touch. (Kidding, not kidding.)

I actually don’t read the new books quick. Never have. For one, I like to pay paperback prices. For two, I like to see the consensus about a book after some time has passed and various opinions have gelled. When I read a new book, it’s pretty random. But after the excitement of James, I was happy to go ahead. I had been wanting to read Percival Everett after his book, Erasure, was made into what was my favorite movie of 2023, American Fiction. But I was also suspicious that the popularity of James had something to do with the movie’s release (and its Oscar nom right before the book’s publication). Let me see…

James by Percival Everett is a retelling of Mark Twain’s classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. But this time, we hear the story through the perspective of the runaway slave, Jim. And it’s not just a perspective change; we realize rather quickly that Jim—or James, as he prefers—has several secrets that run in the story’s background we thought we knew, so that it changes the meaning of much of what we see on the page. Because James isn’t just any ol’ Black man in the antebellum South; no, he’s subversive and motivated and very intelligent. And maybe, perhaps, he isn’t even the only one.

I mean, this book isn’t meant to reflect history, exactly. Nor is it supposed to be realistic, I think. We are supposed to see James as the potential of the Black slaves more than an actual, historical figure. I think. And it’s also a way of turning Twain on its head so that we read new (and deeper) and exciting things into it. After all the hubbub, I still didn’t really know what to expect, so I needed some time to acclimate, to figure out what I was reading, exactly. It had something to say about history, something to contribute to our reading of Twain and our understanding of the times, but through an almost magical-realism shift. Or maybe not magical realism, but an exaggerated child character (Twain’s) with really real foibles and then an exaggerated slave character (Everett’s) with really real foibles. Actually, James ends up being more realistic than Huck, whose naivety and penchant for fables is highlighted in James. Yet I hate to put it that way, because even with the wild, near-magical tea that this story is steeped in, there are also brutal, violent, harsh, very real and historic (and also universal) truths.

On one hand, it’s like a play-by-play re-telling of the whole Huck Finn book, and it only changes in the spaces where Huckleberry’s experience (and tall tales) didn’t go in the original. And I don’t just mean when Huck leaves the room—I also mean in James’ mind-space, in the adult reading of a situation, etc. In that sense, the book is rather clever. And it is also written so neatly. Clean. Clear. Readable. Straightforward. Like Twain with just a touch more flourish. A touch. The only bummer here is that a reader is likely to be affected by the enthusiasm of the surrounding people (and the institutions) before they even pick the book, so that there’s only one way to go with their opinion. I can’t say this was my favorite read of the year. It wasn’t, actually. But it is a good book. And it’s solid. And it should stick around and be read for generations. Yes.

As for the twists, I saw them coming, and I bet that’s one reason people really liked this book. So maybe don’t guess. Just enjoy the ride. But speaking of…

You do not have to read Huckleberry Finn before reading James. You most certainly don’t have to read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer before reading Huck Finn before reading James. But I read Huck Finn first and I would recommend it. If you are the type of person who will read a short classic novel before the modern response of a popular literary novel, then you definitely should. If you won’t, then I suppose just read James without, as opposed to missing out altogether. Reading Huck Finn gave me all sorts of perspective and understanding that I wouldn’t have had without it. And it was fun to compare the works basically scene by scene. I had just read it, so I could notice even the minor differences which were always meant to contribute something to the reader’s understanding of this world, of the story, of the history, etc.

I read the oldest copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain in existence. Just kidding; that would be worth a lot of money and I would be selling it, not reading it. But it’s a very beat-up paperback from a 1960s printing. The cover price says 45 cents and sometimes pages would fall out. I have no idea where I got it from.

I almost stopped reading, actually. Sure, the language is a bit archaic, and the accents take like three times as long to read as normal writing, but it wasn’t that. It was the child abuse. I knew the n-word was coming and I knew the book was written in pre-Civil War America, taking place in the South. So I was ready for that. But what no one seems to have mentioned before is the sheer amount of child neglect, abandonment, abuse, kidnapping, imprisonment and torture that takes place in the first few chapters. And delivered with a shrug, with levity and acceptance from the child’s point of view? Quite frankly, I found it brutal in a strange, detached, and I wanted to walk away, especially if it wasn’t going anywhere.

But I asked a friend. He said it would be worth it.

Having finished it, and especially after having read it and then James (with its adult perspective), I agree. It was worth it. But it was difficult and also felt anachronistic. I mean, you have this feral, childlike child (I’m not going to call him innocent, but there is that element to him) and he’s just casually recounting his abuse and neglect. Then you throw in some of Tom—with his stable home and his pretending to be the ruffian he isn’t. And you throw in the culture’s decades of absorption of Huck and Tom Sawyer and rafting on the Mississippi. The biggest thing I remember about Tom and Huck from my childhood was Tom Sawyer’s Island at Disney World and running through the mine shafts and boating across the water. No child abuse there.

I had a sense, too, that Twain wasn’t just presenting this reality because he saw it as normal and we, as a society, have just changed. I have a sense, instead, that he knew what he was doing giving Huck and Tom these totally opposed perspectives and infusing Huck with both troubles and naivety, for he is really gullible and also very full of stories. In other words, he believes Tom’s stories. And he doesn’t understand Jim’s situation. Because while Huck’s poor and neglected, he’s still white. There is so much going on in this text and it would take a class to truly understand both Samuel Clemmons (Mark Twain) and the history, and what Twain was doing with literature in the history. I felt like I was only beginning to understand what he was doing, and I might have been hugely misinterpreting some things. It was a long time ago. And I don’t know diddly about Twain except all the buzzy, inconsequential stuff.

That might be another suggestion: get some sort of commentary (even a quick one) on Huckleberry Finn. Read that after you read Huck Finn but before you read James. Then watch a video or something where Everett talks about James. I don’t think that the author always knows exactly what their book is truly doing and how it’s interacting with readers and society, but it would give you some idea on the intent. As for Huck Finn, it will only help to have more context and history to accompany it. There is an article HERE which could work. (Full disclosure: I used to work for Gale way back in the day, in one of its iterations as The Gale Group.)

Also note the “the adventures of” in the title. This is a story, and it has a story arc, but it is also a collection of adventures. It gets a little episodic at times, a little off the beaten path. Because it is the adventures of Huck. Not the adventure. You might get a little bored or put the book down now and again. I suppose the original idea was to read a bit at bedtime every night. “What’s that crazy Tom Sawyer and his rowdy friend Huck up to this time?” Like a radio show.

So yeah, James is definitely worth the read. And The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is worth the read as preparation for James. Technically, Huck Finn is children’s literature, but there is a lot more going on there than just for kids. And you will get a lot more out of James if you have read Huck Finn at least once, preferably close in time to reading James. People are loving this book, just as people of the past loved the original. The two of them will go down as American classics (well, one already has), linked by the patched-elbow arms, sucking on a couple of pipes.

PS. James is not funny. Don’t believe the book cover. It is betimes violent and brutal and disturbing, as the South being travelled by a runaway slave would be. The magical nature of it allows Everett to gather in most of the worst scenarios in one text, in fact, so that we have to stare history in the face.

“The only ones you suffer when they are made to feel inferior is us. Perhaps I should say ‘when they don’t feel superior'” (James, p21).

“I could see that anything I thought was good could entail some bad consequences” (p72).

“White people love feeling guilty” (p77).

“Good ain’t got nuttin’ to do wif da law” (p78).

“‘But if you make it,’ Old George said, ‘no whipping in the world could undo the hope you will give us.’ / ‘That’s bullshit,’ Pierre said. ‘A lashing is a lashing. No thought in the world will stop the bleeding and the scarring'” (p94).

“But our sympathetic suffering was nothing like Young George’s. That hurt most” (p96).

“After being cruel, the most notable white attribute was gullibility” (p106).

“‘Yes, but them people liked it, Jim. Did you see their faces? They had to know them was lies, but they wanted to believe …. .’ / ‘Folks be funny like dat. Dey takes the lies dey want and throws away the truths dat scares ’em'” (p126).

“A distance you know is shorter den one you don’t” (p138).

“But running and escaping were not the same thing” (p138-139).

“If you’re not making mistakes, you’re not learning” (p153).

“You might be the reason, but it ain’t your fault” (p179).

“Bad as whites were, they had no monopoly on duplicity, dishonesty or perfidy” (p195).

“And yet, with all that running, no place appeared like a new place. Perhaps that was the nature of escape” (p220).

“Hope? Hope is funny. Hope is not a plan. Actually, it’s just a trick. A ruse” (p276).

“I hated the world that wouldn’t let me apply justice without the certain retaliation of injustice” (p280).

“Was it evil to kill evil?” (p284).

“…If you are anywheres where it don’t do to scratch, why you will itch all over in upward of a thousand places” (p6, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn).

“…but I’d druther been bit with a snake than pap’s whisky” (p68).

“…en trash is what people is dat puts dirt on de head or dey fren’s and makes ’em ashamed” (p109).

“…for what you want, above all things, on a raft, is for everybody to be satisfied, and feel right and kind towards the others” (p159).

“…it’s the little things that smooths people’s roads the most…” (p243).

“That’s just the way: a person does a low-down thing, and then he don’t want to take no consequences of it. Thinks as long as he can hide, it ain’t no disgrace” (p271).

“You can’t pray a lie–I found that out” (p272).

“It shows how a body can see and don’t see at the same time” (p296).

March 11, 2025

Book Review: And Then There Were None

Do I need to give a synopsis for And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie? It’s a classic. Well, I will anyhow.

Ten people across England get an alluring message from a Mr. and Mrs. Owen asking them to come to an isolated island off the coast of Devon. After they arrive, a disembodied voice recites a guilty secret for each of them. By the time dinner is over, one of them is dead and they realize they are all next, one by one. With a storm cutting them off from any help they might have received, they have to figure out who is killing them before they all wind up dead.

In other words, it’s a classic set-up. But it’s a classic set-up partly because Agatha Christie made it a classic. And this is one of her most quintessential books. (Did you know that after the Bible and Shakespeare, Christie is the most published author? It says that like three times on my copy of the book.) Which is why my beta readers for my YA supernatural mystery gave me the homework of reading And Then There Were None, a book I have meant to read for years. (They also gave me the homework of making a chart for my suspects and clues. Well, and ripping apart and rebuilding my book.)

Yeah, I liked the book. It was fun to read. It was clear and clean and I always wanted to pick it back up because whodunnit?. And Then There Were None is a mystery and Agatha Christie writes world-famous mysteries. However, this book is almost an exception: it is also horror/psychological horror. It has elements of every slasher film that would come after it. And it is also a trip into Vera’s mind and a book about guilt and justice.

The story is brisk. The writing is high and tight. The thoughts, words, perspectives, swirl yet are almost poetic in the sparseness. Nearly every sentence serves a quick purpose and a long one. At times I was annoyed that there were so many perspectives (eight to ten of them, some leaned on much more heavily than others), but at other times it was fun, and I was both needled and electrified (no puns intended) by the times I might be in the killer’s head (but didn’t know it! If I’m not mistaken, there were two to three sentences in the book that were thoughts straight from the killer’s head. Whole novel idea!) I was turning those pages, wanting to know who was next and who the killer(s) was. And I approve of the gimmicks like the nursery rhyme (except the specific nursery rhyme, which we’ll talk about in a sec), the POVs (probably) having to include the killer’s, and, well, whatever the killer threw at us (like the isolated island). A little splash is necessary to create some fun (and respectableness) in an otherwise straightforward-genre mystery.

I do think there is one flaw in the story, besides the fact that it is nearly impossible—based on information given—to figure out the murderer by the end. (There’s one simple clue that I think could have been included that would have given us a fighting chance. Who knows? Maybe it was actually there and I missed it. It’s worth noting that the movie included it (and I had already written this line before I watched the movie.)) Eventually, we are given the explanation and it’s quite clever. And I won’t give anything away, but there is one murder after which the characters don’t respond quite as thoroughly, especially considering one concern I had as the reader, and this ends up being to the advantage of the author. Christie moves quickly along, hoping I will forget these particular misgivings. (I basically did.) The plot could have fallen apart at that point if the characters played it differently, which makes the killer’s plan just one tiny hole shy of watertight.

So, there are some issues with this book that we need to talk about. Maybe you already know. In the 1930s, this book was first published with the title Ten Little [N-word]s (please excuse me for not quoting the word like an academic, but I am attempting to be sensitive and I’m also reluctant to have it appear on the blog), but wasn’t released under that title in the U.S, where it changed to And Then There Were None. It was later renamed Ten Little Indians (maybe because the song was originally “Ten Little Indians”?). The title is just the start. There are many references on the pages to the poem, related objects, etc. And the poem is really violent and offensive (beyond what people-group or terminology you use) because it includes several violent deaths. Now the book is published with the people in the poem and the statues as “soldiers” (instead of Golliwogs—like offensive caricature dolls of Black people). The characters now go to Soldier Island, and the title is, of course, back to And Then There Were None, which is the last line of the poem.

And it’s still one of the best-selling books of all time and the miniseries was a huge hit in England.

Here’s the thing—the book’s been largely scrubbed clean of the racist bullpoop related to the song that is used to set up the murders. I think that we, as a world, have done this instead of walking away from the book because the racist slurs are the set-up (that existed already in the world), and the story itself has nothing to do with that (at least in the version I can buy new on a shelf today). There still is some racist, misogynistic, and other problematic sentiment shared in the book, but these are opinions (and actions) of the characters, used to develop them and reflect the times. The book was updated, then, and we kept reading it because it’s such a popular and, for the genre, foundational book. I am not super comfortable with this white-washing, but I also wouldn’t buy a book with “Ten Little [N-word]s” emblazoned on the front cover. (I do have some suspicions about the removal of some antisemitic content, as well, but what I’m saying is that I don’t see this controversy as necessarily reflective of anything in Christie or the spirit of the book as more than a product of her (its) times and, well, callously flippant, perhaps.) For what it’s worth, I am anti-banned-books. But I think it’s important to understand the history here. Also, if I don’t tell you, someone else will. It’s very common literary lore.

I’m not so sure, either, about the way women are portrayed, even in the newest versions. I just blogged about a slap scene in my review of Lucky Jim, where a young woman melted down and then a man slapped her and she thanked him. Well, here we go again. Same. Stupid. Scene. (Clears my throat.) Ya’ll! It’s some sort of early twentieth century literary convention, but it’s a stupid one, and one that is patronizing and misogynistic. I’m not going to change how people wrote in the past, but I’m gonna call it out now. This is unreal crap! Though overall—maybe because Christie is a woman—Vera is the most well-drawn character, the one with the most depth and relatability (though how much is that saying?).

Even after reading And Then There Were None—a book I enjoyed and can appreciate on several levels—I don’t want to read tons of mysteries. I read Christie on one other occasion, for Christmas, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas. Quite frankly, the repetition of the mystery genre tends to bore me, even as some people can read it exclusively and voraciously. Maybe they’re finding exciting new iterations? On the whole, I don’t think so. Sticking to a solid genre like that is more of comfort-reading, I think. A relaxing thing. (The way I might occasionally read a romance.) But I want my mystery mixed with other things, going in new directions and surprising me, even as the conventions are followed. Excuse me while I look up best mysteries of all time…

Beep, beep, boop.

Here is the Starving Artist’s list of best mysteries, compiled from other lists across the web-verse. I have only read and reviewed the ones with links.

Murder on the Orient Express, Agatha Christie The Hound of the Baskervilles , Sir Arthur Conan DoyleThe Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett Dracula , Bram StokerThe Big Sleep, Raymond Chandler The Silent Patient , Alex MichaelidesThe Name of the Rose, Umberto EcoTourist Season, Carl HiaasenAgatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot seriesIn the Woods, Tana French (and the Dublin Murder Squad)The Silence of the Lambs, Thomas HarrisRebecca, Daphne du Maurier Still Life , Louise Penny (and the Inspector Gamache series)Tales of Mystery and Imagination, Edgar Allan PoeThe Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Mark HaddonMotherless Brooklyn, Jonathan LethemThe Deep Blue Goodbye, John D. McDonald Gone Girl, Gillian FlynnThe Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Steig LarssonDevil in a Blue Dress, Walter MosleyThe No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, Alexander McCall SmithThe Bat, Jo NesboOne by One, Ruth WareMaximum Bob, Elmore LeonardThe Decagon House Murders, Yukito AyatsuiShutter Island, Dennis LehanePostmortem, Patricia CornwellWhose Body?, Dorothy L. SayersPleasantville, Attica LockeBury Your Dead, Louise PennyThe Woman in White, Wilkie CollinsThe 7 1/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, Stuart TurtonThe Sherlock Holmes series by Sir Arthur Conan DoyleThe Honjin Murders, Seishi Yokomizo We Have Always Lived in the Castle , Shirley JacksonThe Snowman, Jo Nesbo In Cold Blood , Truman Capote Never Let Me Go , Kazuo IshiguroThe Eyre Affair, Jasper FfordeMexican Gothic, Silvia Moreno-GarciaKilling Floor, Lee ChildWinter Counts, David Heska Wanbli WeidenThe Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John Le CarreThe Daughter of Time, Josephine TeyDrive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Olga TokarczukThe Shining, Stephen KingThe Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Michael ChabonAltered Carbon, Richard K. K. MorganA Is for Alibi, Sue GraftonThe Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Agatha ChristieAnatomy of a Murder, Robert TraverCrime and Punishment, Fyodor DostoevskyThe Turn of the Screw, Henry JamesBig Little Lies, Liane MoriartyEverything I Never Told You, Celeste NgMystic River, Dennis LehaneBlacktop Wasteland, S. A. Cosby2666, Robert BolanoTell No One, Harlan CobenCase Histories, Kate AtkinsonThe Sympathizer, Viet Thanh NguyenCasino Royale, Ian FlemmingThe Long Goodbye, Raymond ChandlerThe Scarlet Pimpernel, Baroness OrczyWhat the Dead Know, Laura LippmanThe Quiet American, Graham GreeneThe Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia HighsmithThe Last Good Kiss, James CrumleyThe Hunt for Red October, Tom ClancyBleak House, Charles DickensThe Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre DumasThe Secret History, Donna TarttThe Sound of Things Falling, Juan Gabriel VasquezThe Round House, Louise Erdrich To Kill a Mockingbird , Harper Lee (a mystery? Hmm…)Six Four, Hideo YokoyamaThe Big Sleep, Raymond ChandlerOrdinary Grace, William Kent KruegerThe Other Americans, Laila LalamiThe Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Haruki MurakamiThe Turn of the Key, Ruth WareThe Savage Detectives, Roberto BolanoRougue Male, Geoffrey HouseholdThe Postman Always Rings Twice, James M. CainTinker Taylor Soldier Spy, John le CarreStrangers on a Train, Patricia HighsmithBrighton Rock, Graham GreeneIf on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, Italo CalvinoThe Godfather, Mario PuzoThe Daughter of Time, Josephine TeyOur Mutual Friend, Charles DickensThe Hollow Man, John Dickson CarrThe Thin Man, Dashiell HammettThe Moonstone, Wilkie CollinsThe Nine Tailors, Dorothy L. SayersGaudy Night, Dorothy L. SayersV., Thomas PynchonBeast in View, Margaret MillarFingersmith, Sarah WatersThe Franchise Affair, Josephine TeyThe Mysteries of Udolpho, Ann RadcliffeAn Unsuitable Job for a Woman, P. D. JamesSkinwalkers, Tony HillermanVelvet Was the Night, Silvia Moreno-GarciaGet Short, Elmore LeonardThe Lincoln Lawyer, Michael ConnellyBury Your Dead, Louise PennyDo Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Philip K. DickFatherland, Robert HarrisFirst Among Sequels, Jasper Fforde (Thursday Next mysteries)A Study in Honor, Claire O’DellRoman Blood, Steven SaylorFinlay Donovan Rolls the Dice, Elle CosimanoDial A for Aunties, Jesse Q. SutantoThe Secret of the Lady’s Maid, Celeste ConnallyThe Wisteria Society of Lady Scoundrels, India HoltonThe Orinthologist’s Field Guide to Love, Indian HoltonThe End of Everything, Megan AbbottStation Eleven, Emily St. John MandelJonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, Susanna ClarkeBel Canto, Ann Patchett A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder , Holly Jackson We Were Liars , E. LockhartThe Agathas, Kathleen Glasgow and Liz Lawson One of Us Is Lying , Karen M. McManusLittle Monsters, Kara ThomasThe Inheritance Games, Jennifer Lynn BarnesThe Girls I’ve Been, Tess SharpeThe Darkest Corners, Kara ThomasThese Shallow Graves, Jennifer DonnellySadie, Courtney SummersA Study in Charlotte, Brittany CavallaroStalking Jack the Ripper, Kerri MoniscalcoFirekeeper’s Daughter, Angeline BoulleyPaper Towns, John GreenI Am the Messenger, Markus Zusak(I made sure to include some cross-genre mysteries as well as YA (largely at the bottom) because YA seems to have this genre down lately and we’d be missing out by not including it.)

So please note the historical and racial issues in this novel’s past. The story itself is tight and engaging and clean. It does make you think about guilt and justice, sure, but mostly it’s just a good time trying to figure out whodunnit, if you want to circumvent the historic racism to get there. Or at least acknowledge it.

“Half the women who consulted him had nothing the matter with them but boredom, but they wouldn’t thank you for telling them so!” (p10).

“My dear lady, in my experience of ill-doing, Providence leaves the work of conviction and chastisement to us mortals—and the process is often fraught with difficulties. There are no short cuts” (p80).

“When a man’s neck is in danger, he doesn’t stop to think too much about sentiment” (p82).

“My dear young lady, this is no time for refusing to look facts in the face” (p123).

“One more of us acquitted—too late!” (p165).

“But no artist, I now realize, can be satisfied with art alone. There is a natural craving for recognition which cannot be gainsaid” (p246).

My husband and I watched the 2015/6 miniseries of two episodes (1.5 hours each) from the BBC. Maybe I should have watched the old one (1945—the best, according to lots of people). There are other versions, but unless you are going to write a thesis on it, you could stop there.

The 2015 miniseries version had the volume up, which did a disservice to one theme of the book (which was that these people were kinda like us and that their murders were not only crimes of omission and sometimes crimes of distance, but that they were also crimes that would not be traditionally punishable). Also, the violence and sex: I get it for the modern viewer, but it was wholly unnecessary for the story. It just wasn’t needed, and it only took away from the cleanness and emotional trajectory of the original. Well, maybe not only. I kinda get what they were doing, but they just massacred some of these characters’ character, their back story, and any subtlety of the original. I’m not a Neanderthal. I don’t need you to keep me watching with blood! and sex! and violence! I was happier with the story more nuanced. Still, it was pretty good as a miniseries, and we enjoyed watching it. Let me rephrase that: we didn’t regret it.

March 7, 2025

Book Review: Lucky Jim

Comedy is really social, maybe even socio-political. Which is why a book like Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis hasn’t aged well. It’s funny (I can see that, or at least some of that), but the British academic satire from the 50s was mostly beyond me, at least emotionally. There were a few scenes that I was laughing out loud (and the most amazing hangover paragraph), but I couldn’t wrangle quite the enthusiasm that Amis’s contemporaries did. Even still, and besides some wandering away from it out of disengagement, I liked it. Just for how much longer will people even be able to relate to this humorous classic, though?

Jim is a professor (not the terminology here) of Medieval History at maybe not the most prestigious school because that’s the job that he could get. And he’s not very enthusiastic about his job, about his profession, about his lot in life. He’s just going to float along doing the least amount of work that he can, all the way through his probationary year the same way he’s floating through his almost-relationship with the only available woman his age, Margaret. But as his review approaches, he senses his job is very much on the line at the same time he’s sorta got a thing for his clueless boss’s pompous son’s disaffected girlfriend. And Jim just can’t help himself: he’s fond of evading responsibility, making wild faces, and pulling pranks.

I grew up with a certain level of Monty Python. This book read to me like Monty Python meets The (American) Office with its brand of physical humor and mocking satire. Which may seem weird because it’s a book, not a movie. Which was one of the things I found most impressive about this book: the way that it somehow dialed in the physical humor in the literary form. I have never read another book quite like that, and once I saw it for what it was, I was impressed.

Still, as I implied above, this book was not meant for me. It was written in the late forties, early fifties and is British. Humor doesn’t translate enormously well across time and cultures, despite the luck of someone like Jane Austen. And this is comedic writing. It also has its satirical finger very closely on the pulse of academic life in English colleges in the forties, and, yeah, there was a lot to miss here (was there something about the Welsh?!) because of that. However, I can appreciate several things about it: the glimmer of humor and satire that I can almost get, that I can tell is there; the humor that does translate and is pretty darn funny; the writing style coming across as this amazing, dysthymic rom-com (a la Garden State or Ghost World or Eagle Versus Shark or something). I can understand the reverence others have for it.

But let’s not get too carried away with the rom in the rom-com. I wasn’t even sure it was going to be a romance until very late in the book. And I was on tenterhooks about which direction we were going here: romance or anti-romance. Like until the last pages. (I won’t tell you.) Also, more importantly, the women characters are just horrific. This is expected from a male writer in the 1940s, but in a couple scenes it is so bad. And the book had this scene where one of the women had a nervous breakdown (so we would have called it back when we thought this was still a real thing) and a male character slaps her and that makes her come around. Then she thanks him. Giant sigh. I have read this scene no less than three times in my reading adventures, most recently in And Then There Were None (review forthcoming), and it is always an eye-roller. First off, did the “brain fever” of Victorian times (and all that bed rest!) become the meltdown and healing slap of the early twentieth century? None of it can possibly be a reflection of reality. And must the woman always thank the guy who hits her in these scenes? (Yes. The answer is yes.) See?: big sigh.

Then again, this book is not meant to be taken seriously, and we might want to keep in mind that the woman in question is playing these men. There are things being said about class and nationality and, who knows?, maybe gender roles too. But the last of these just reads as simply outdated because, let’s face it, it is. Quite. There is some great wordsmithing. And at book club we all laughed together as we remembered some of the scenes. I really liked the writing style, and I liked the context.

Who would I recommend read this? Someone who has been assigned it for book club, for one. It’s worth the read. It’s short. But there will be some struggling along with the laughs and the admiration. Other than that? People who insist on reading all the classics. Or people who have a 1940s British academia fetish.

“For a moment he felt like devoting the next ten years to working his way to a position as art critic on purpose to review Bertrand’s work unfavourably” (p47).

“A stimulus cannot be received by the mind unless it serves some need of the organism.’ He began laughing, an action he soon modified to a wince” (p61).

“This, of course, would give him time to collect his thoughts, and that, of course, was just what he didn’t want to do with his thoughts; the longer he could keep them apart from one another, especially the ones about Margaret, the better” (p62).

“…the possession of the signs of sexual privilege is the important thing, not the quality nor the enjoyment of them. Dixon felt he ought to feel calmed and liberated at reaching this conclusion, but he didn’t, any more than unease in the stomach is alleviated by discovery of its technical name” (p109).

“It was doubtful, he considered, whether he was capable of being at all sweet, much less ‘so’ sweet, to anybody at all. Whatever passable decent treatment Margaret had had from him was the result of a temporary victory of fear over irritation and/or pity over boredom” (p113).

“All the same, what messes these women got themselves into over nothing. Men got themselves into messes too, and ones that weren’t so easily got out of, but their messes arose from attempts to satisfy real and simple needs” (p117).

“Another thing you’ll find is that the years of illusion aren’t those of adolescence, as the grown-ups try to tell us; they’re the ones immediately after it, say the middle twenties, the false maturity if you like, when you first get thoroughly embroiled in things and lose your head” (p127).

“This ride, unlike most of the things that happened to him, was something he’d rather have than not have” (p143).

“Words change the thing…” (p148).

“Don’t be fantastic, Margaret. Come off the stage for a moment, do” (p165).

“Oh, of course, Professor; I’m sorry,’ he said, having been well schooled in giving apologies at the very times when he ought to be demanding them” (p181).

“Doing what you know you’ve got to do’s horrible sometimes, but that doesn’t mean to say it isn’t worth doing” (p211).

“But, anyway, he’d met her and talked to her a few times. Thank God for that” (p259).

My husband and I turned on the movie from the 50s. We didn’t make it very far before we turned it off. It has that overbearing 1950s aura and, what’s more, we were thoroughly bored.

March 6, 2025

What to Read in March 2025

In the past year I have read a few Irish books that I loved. Let’s throw those out there for suggested St. Patty’s Day reading:

Prophet Song, Paul Lynch. Prophet Song is a book I keep recommending to people as “my favorite read of the year, last year.” It was also one of my first reads in 2024. People keep getting back to me to thank me for this recommendation. I don’t know if it’s the cover or the title—neither of which do the book a service—but this book isn’t getting as much attention as it deserves, even after the 2023 Booker Prize. I don’t want to talk it up so much you are disappointed, but once I got used to the unconventional writing style/POV (which is actually pretty normal for Irish writers), I was blown away by the beauty of the writing and the authenticity of the main character, a mother during an alternate-history break-down of Irish democracy.Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell. Irish author, but it takes place in Renaissance England. Cuz it’s about Shakespeare, though we never actually see his name on the page. Really, it’s about his family, and especially his wife as she deals with the death of their son, Hamnet, and her husband’s frequent absence. More beautiful language and surprising ways of presenting things. I am a Renaissance England kind of person, and I really loved this book.The Marriage Portrait, Maggie O’Farrell. Irish author, but it takes place in Italy (16th century Florence). I was so enamored by Hamnet that I wanted to dive into O’Farrell’s backlist. Alas, I have other pressing TBRs, but I did manage to read this one, her latest. It was “lush,” as I said in my review, the language beguiling me yet again. I had some complaints about tenses and also the ending, but overall, it was another big win for O’Farrell, for me.Trespasses, Louise Kennedy. I gave this one 3.5 stars, but I thought for the many of you who praise this book, I would include it here. I didn’t hate it, though the more I thought about it, the madder I actually was at it. And it’s one of those young-girl, older-married-man affair books, which I have very little patience for to begin with. But it takes place in the Troubles and explores Protestant-Catholic relationships and realities.Normal People, Sally Rooney. This is one of my daughter’s favorite books, as it is many other people’s (especially younger people). It is also a popular movie. I was not as enthusiastic as my daughter (or many of you) on this one, but I would still recommend it. On the blog, I said, “Here’s my very abbreviated two cents: it’s a realistically swirling tale, told with impressive, clear prose.” In the end, I think the character development suffered for it, unfortunately. Millennials do not agree with me.

Prophet Song, Paul Lynch. Prophet Song is a book I keep recommending to people as “my favorite read of the year, last year.” It was also one of my first reads in 2024. People keep getting back to me to thank me for this recommendation. I don’t know if it’s the cover or the title—neither of which do the book a service—but this book isn’t getting as much attention as it deserves, even after the 2023 Booker Prize. I don’t want to talk it up so much you are disappointed, but once I got used to the unconventional writing style/POV (which is actually pretty normal for Irish writers), I was blown away by the beauty of the writing and the authenticity of the main character, a mother during an alternate-history break-down of Irish democracy.Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell. Irish author, but it takes place in Renaissance England. Cuz it’s about Shakespeare, though we never actually see his name on the page. Really, it’s about his family, and especially his wife as she deals with the death of their son, Hamnet, and her husband’s frequent absence. More beautiful language and surprising ways of presenting things. I am a Renaissance England kind of person, and I really loved this book.The Marriage Portrait, Maggie O’Farrell. Irish author, but it takes place in Italy (16th century Florence). I was so enamored by Hamnet that I wanted to dive into O’Farrell’s backlist. Alas, I have other pressing TBRs, but I did manage to read this one, her latest. It was “lush,” as I said in my review, the language beguiling me yet again. I had some complaints about tenses and also the ending, but overall, it was another big win for O’Farrell, for me.Trespasses, Louise Kennedy. I gave this one 3.5 stars, but I thought for the many of you who praise this book, I would include it here. I didn’t hate it, though the more I thought about it, the madder I actually was at it. And it’s one of those young-girl, older-married-man affair books, which I have very little patience for to begin with. But it takes place in the Troubles and explores Protestant-Catholic relationships and realities.Normal People, Sally Rooney. This is one of my daughter’s favorite books, as it is many other people’s (especially younger people). It is also a popular movie. I was not as enthusiastic as my daughter (or many of you) on this one, but I would still recommend it. On the blog, I said, “Here’s my very abbreviated two cents: it’s a realistically swirling tale, told with impressive, clear prose.” In the end, I think the character development suffered for it, unfortunately. Millennials do not agree with me.

What are we looking forward to in March? Besides St. Patty’s Day and Fat Tuesday (because of paczkis)? Oh, and the year to finally begin for reals and stop being a nightmare? (We can hope.)

Here are some highly anticipated March new releases:

Dream Count, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (literary fiction)Wild Dark Shore, Charlotte McConaghy (psychological thriller)This Book Will Bury Me, Ashley Winstead (mystery thriller)The Dream Hotel, Laila Lalami (sci fi-thriller-lit fic)When the Moon Hits Your Eye, John Scalzi (sci fi)Dissolution, Nicholas Binge (time travel thriller)The Unworthy, Agustina Bazterrica (dystopian horror)The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, Stephen Graham Jones (horror)Oathbound, Tracy Deonn (Legendborn Cycle #3, YA fantasy)Our Infinite Fates, Laura Steven (YA romantasy)They Bloom at Night, Trang Thanh Tran (YA queer body horror)Sunrise on the Reaping, Suzanne Collins (YA fantasy, in the Hunger Games world)Everything Is Tuberculosis, John Green (nonfiction, history-science-culture)I Leave It Up to You, Joo-Win Chong (literary fiction)A Gentleman’s Gentleman, TJ Alexander (transgender Regency romance)Raising Hare, Chloe Dalton (nature memoir)The Antidote, Karen Russell (historical fiction/magic realism)Stag Dance, Torrey Peters (transgender multi-genre story collection)Care and Feeding, Laurie Woolever (food memoir)On Air, Steve Oney (NPR history)Early Thirties, Josh Dubuff (romance)Saving Five, Amanda Nguyen (magical realism memoir)Theft, Abdulrazak Gurnah (historical fiction family drama)Tilt, Emma Pattee (literary mystery thriller—see a title trend?)Twist, Collum McCann (which could also double as a St. Patty’s Day read)

Dream Count, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (literary fiction)Wild Dark Shore, Charlotte McConaghy (psychological thriller)This Book Will Bury Me, Ashley Winstead (mystery thriller)The Dream Hotel, Laila Lalami (sci fi-thriller-lit fic)When the Moon Hits Your Eye, John Scalzi (sci fi)Dissolution, Nicholas Binge (time travel thriller)The Unworthy, Agustina Bazterrica (dystopian horror)The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, Stephen Graham Jones (horror)Oathbound, Tracy Deonn (Legendborn Cycle #3, YA fantasy)Our Infinite Fates, Laura Steven (YA romantasy)They Bloom at Night, Trang Thanh Tran (YA queer body horror)Sunrise on the Reaping, Suzanne Collins (YA fantasy, in the Hunger Games world)Everything Is Tuberculosis, John Green (nonfiction, history-science-culture)I Leave It Up to You, Joo-Win Chong (literary fiction)A Gentleman’s Gentleman, TJ Alexander (transgender Regency romance)Raising Hare, Chloe Dalton (nature memoir)The Antidote, Karen Russell (historical fiction/magic realism)Stag Dance, Torrey Peters (transgender multi-genre story collection)Care and Feeding, Laurie Woolever (food memoir)On Air, Steve Oney (NPR history)Early Thirties, Josh Dubuff (romance)Saving Five, Amanda Nguyen (magical realism memoir)Theft, Abdulrazak Gurnah (historical fiction family drama)Tilt, Emma Pattee (literary mystery thriller—see a title trend?)Twist, Collum McCann (which could also double as a St. Patty’s Day read)Some Ireland-related reads that I have not read yet:

The book at the top of my list this year for St. Patty’s Day is Tana French’s In the WoodsMaggie O’Farrell, This Must Be the PlaceCircle of Friends, Maeve BinchyUlysses, James JoyceDubliners, James JoyceEverything in the Country Must, Cullum McCannThe Commitments, Roddy Doyle

The book at the top of my list this year for St. Patty’s Day is Tana French’s In the WoodsMaggie O’Farrell, This Must Be the PlaceCircle of Friends, Maeve BinchyUlysses, James JoyceDubliners, James JoyceEverything in the Country Must, Cullum McCannThe Commitments, Roddy DoyleAs for which books coincide with Oscar nominations… (There are a lot less this year than last.)

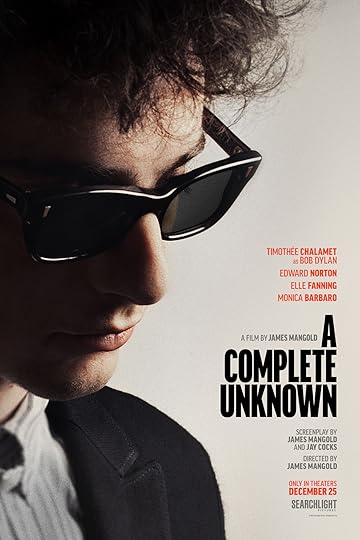

Wicked, Gregory Maguire (Wicked)Conclave, Robert Harris (The Conclave)The Nickel Boys, Colson Whitehead (The Nickel Boys)Dune, Frank Herbert (Dune: Part Two)The Wild Robot, Peter Brown (Wild Robot)Dylan Goes Electric!, Elijah Wald, (A Complete Unknown)Black Box, Shiroi Ito (Little Black Box)Magic Candies, Paek Hui-Na (Magic Candies)

Wicked, Gregory Maguire (Wicked)Conclave, Robert Harris (The Conclave)The Nickel Boys, Colson Whitehead (The Nickel Boys)Dune, Frank Herbert (Dune: Part Two)The Wild Robot, Peter Brown (Wild Robot)Dylan Goes Electric!, Elijah Wald, (A Complete Unknown)Black Box, Shiroi Ito (Little Black Box)Magic Candies, Paek Hui-Na (Magic Candies)

Not as enthusiastic about these as some months, for sure. Except The Eyes & the Impossible. February just wasn’t the best reading month for me, for some reason. But I can still recommend these:

The Vegetarian

, Han KangThe Eyes & the Impossible, Dave EggersOrbital, Samantha Harvey

Julie Chan Is Dead,

Liann Zhang (out at the end of April)

The Vegetarian

, Han KangThe Eyes & the Impossible, Dave EggersOrbital, Samantha Harvey

Julie Chan Is Dead,

Liann Zhang (out at the end of April)

I’m in six book clubs. The list below means I’m skipping one this month.

Dear Life, Alice MunroA Study in Charlotte, Brittany CavaralloOlga Dies Dreaming, Xochitl GonzalezHouse of Fury, Evelio RoseroThe First Sister, Linden A. Lewis

Dear Life, Alice MunroA Study in Charlotte, Brittany CavaralloOlga Dies Dreaming, Xochitl GonzalezHouse of Fury, Evelio RoseroThe First Sister, Linden A. Lewis

And Then There Were None

, Agatha ChristieBig, HarrisonIn the Woods, Tana FrenchMurder by Cheesecake, Rachel Ekstrom Courage (ARC)The Three-Body Problem, Cixin LiuA Family Matter, Claire Lynch (ARC)The Story, GodWorth Fighting For, Jesse Sutanto (ARC)The Familiar, Leigh BardugoHow to Learn to Be Brave, Mariann BuddeThe Hate U Give, Angie ThomasThe Fraud, Zadie SmithDark Forest, Cixin LiuSome Desperate Glory, Emily TeshLost Man’s Lane, Scott CarsonThe Commitments, Roddy DoyleThis Must Be the Place, Maggie O’Farrell

And Then There Were None

, Agatha ChristieBig, HarrisonIn the Woods, Tana FrenchMurder by Cheesecake, Rachel Ekstrom Courage (ARC)The Three-Body Problem, Cixin LiuA Family Matter, Claire Lynch (ARC)The Story, GodWorth Fighting For, Jesse Sutanto (ARC)The Familiar, Leigh BardugoHow to Learn to Be Brave, Mariann BuddeThe Hate U Give, Angie ThomasThe Fraud, Zadie SmithDark Forest, Cixin LiuSome Desperate Glory, Emily TeshLost Man’s Lane, Scott CarsonThe Commitments, Roddy DoyleThis Must Be the Place, Maggie O’Farrell

February 28, 2025

ARC Review: Julie Chan Is Dead

I think Julie Chan is Dead by Liann Zhang—a debut author—has potential to be a hit this summer. (It is due for publication at the end of April). It is an easy read that goes down smooth while also being a roller coaster of an experience. Don’t come here for literary acrobatics, but for social commentary that becomes a thriller that gets violent. Come here for apprehension that turns to dread that sours before more explosive horror. It feels so of the moment to me, in a way that lots of readers—especially new adult—would eat it up and then lick up the crumbs. In a creepy way. While filming it.

Julie Chan is just some young woman who works at the SuperFoods and lives in the run-down house her influencer twin bought her the one time she showed up for her, which turned out to be all for the likes and Benjamins. Which makes Julie mad. Out of the blue, Chloe reaches out to Julie right before Julie finds Chloe dead on the floor—and decides to take over Chloe’s life. But life as an affluent influencer is not exactly what Julie expected, and trying to keep her identity a secret gets even more complicated the deeper she spirals into the vortex that is internet socials and the ominous group of allies Chloe had gotten involved with.

This is my first ARC review as an employee of an indie book store. In other words, this is the first book that I picked up from the box of ARCs in the staff room that I have read and am ready to review for you. I chose this book because it was already on my radar, specifically on my pre-made list of anticipated reads for the year. And it is also the first time I can come to you with a book that I think will actually cause a stir. (Not that it’s the best book, necessarily, but the biggest.)

I kinda like it when a book goes off the rails, but this new generation has really taken it to a new level of trippy psychosis. I mean, I love books like Lincoln in the Bardo (George Saunders) and North Woods (Daniel Mason), but what I see happening in Julie Chan Is Dead is more in alignment with the obsession the younger peeps have for the horror genre, the body horror involved with global and own voices (like South Korean literature (The Vegetarian, The Cabinet) and Andrew Joseph White), and the trippin’ scenes in, well, like everything new. I mean, how many new books or movies have you seen lately that don’t involve a scene where the character(s) is hallucinating? So that we get to “see” what they’re seeing? It’s like a requirement.

Speaking of which, this book makes a great pair with Apple Cider Vinegar, a based-on-a-true-story Netflix limited series (new, reviewed well) about a young woman who fakes cancer in order to gain followers as an influencer. And it’s not just the content that makes them similar; it’s also the tone. (And of course a hallucination scene(s).) Yes, body horror (at least a little). And yes to this seriously ominous, creepy, dark twisting behind the flashy veneer. With both this book and this series, the reader and viewer never feels comfortable, never at ease. There is something sinister in every fiber of the story, no matter how cheery or pleasant the immediate scene is. You’re squirming.

Which is what I did for this entire book. But the way that it is written, the squirms start off just that: squirmy. And the ramp into the downright effed up is veeeery slow. I didn’t mind it because I like books like that. But if you are expecting more of the same from the outset of this book, well you better buckle up. Later. Maybe after about halfway through the book. And those first pages could lose readers who want bat-poop crazy. Hang on, all you youngsters. This is going to be right up your alley soon enough. Relevant. And enjoyable to your particular sensibilities.

Of course, not everyone is going to like it, even when they’ve been warned this gets crazy and dark. That it’s social commentary on social media and the influencer lifestyle and white privilege. That it’s like Yellowface and Bunny (neither of which I’ve read yet). I think the biggest hurdle here after the warning is the writing style. It’s, well, flat. I was going to call it adequate, which is enough for me to enjoy a book. (I don’t do less than adequate.) But there are some early reviewers who think the style, the voice, is meant to be one-dimensional and simple because the narrator is an influencer. I suspect this is giving Zhang too much credit, but we won’t really know that until she gives us another book and we see if she is capable of flexing her writing chops, of expanding her voice library. Either way, I found it adequate writing.

And I would guess there would be a next book, with a new fan base eagerly anticipating it. Raven books has already pre-empted her next title.

I don’t love the cover. I don’t hate it.

Anyways. I was drawn into the book, and it went down easy. Every once in a while, I’d look ahead and think, “How can this book go on this much longer?” But then the gears would shift and I’d see new range. Then I’d wonder how it could go on again. And then the gears would shift. You get my point. It’s a book in stages (which I would say about the one I’m working on, incidentally.) And it’s going to be fun for a lot of readers.

Liann Zhang is second-gen Chinese-Canadian. She was a “skincare content creator” and has degrees in psychology and criminology. Julie Chan Is Dead is her first book.

February 8, 2025

Book Review: Children of Time

My main take-away after reading the enormous (600-page) sci-fi Children of Time by Adrian Tchaikovsky: this is a tale of two styles. The story jumps back and forth between a group of humans on one of the last spaceships in the universe (concentrating on one character, Holsten), and the intellectual and social development of newly sentient alien spiders. I enjoyed the story about the humans. The alien-spider story was dense with details, supposed science, and the historical minutiae of their world. While the concept was intriguing, no thanks. I would have preferred a continuation of the more involved-reader style of the human parts. And moreover, for me it felt like driving home the historical points way too much. Because that’s how I also read this book: as a (thinly veiled) commentary on/retelling of human history. I was almost completely alone in this at book club, like I’m Dr. Kern floating around in a rocket for one, slowly going bonkers…

But I’m totally right. My monkeys! It’s a story about personhood and human nature.

Humanity has fled a dying Earth for the stars and its far-flung terraforming projects. Unfortunately, only one of those projects appears to have worked, and when the humans arrive, they are greeted by giant intelligent (and violent) spiders and a half-human, half-AI guardian hell-bent on a future without one shred of the old humanity. Holsten is just a classicist, but every hundred years or so he gets woken from cryo-sleep and thrown into some fresh chaos in the long-game to reclaim the planet. Meanwhile, the spiders are growing, learning, adapting, and slowly coming to understand that it’s their species or the humans.

Like the characters (human and spider) in this book, I had a journey during the reading of this (again giant) book. I generally like speculative fiction, but I lean more toward fantasy than sci-fi. But I have liked many sci-fi books anyway. Despite its 600 pages and the two months we had to read this one, I was excited because my book club friend said it was one of his favorites. So I jumped right in.

Yeah, not my cup of tea. Somewhere in the first quarter of the book, I started checking out during the spider chapters. I acknowledged the awards (Hugo and Arthur C. Clarke). I saw the ratings (4.3 on Goodreads). But I had basically given up reading with my eyeballs and went to my backup for books I insist on finishing even when I’m slogging through, which is the audio version (where I get trapped in the car with it and forced to continue). While driving in the car with me, my husband—who reads largely scifi and history and loves both scifi and the natural world—agreed: I cannot feel the same way about sentient spiders as I do about humans and there is way too much telling and world-building.

There are two types of speculative fiction reader, after all. There is the high-fantasy kind of reader (I can’t seem to figure out what the sci-fi equivalent of this is called) and there is the low-fantasy kind of reader. But maybe that’s not exactly what I mean. The distinction is more in the level of showing versus telling, in the depth of the details given for the world-building. The Lord of the Rings is clearly high fantasy, but it is borderline when it comes to telling me stuff versus simply immersing me and telling me a story. It is nowhere near the level of backstory deets that are in Children of Time (only related to the spiders, not the humans). The human stories require a significant level of filling in the gaps, of figuring things out with Holsten, just concentrating on the story that is being told. The funny thing is that we had an extra-large turnout for book club this month (it is January) and out of something like 50 people I was one of only two (!) who liked the human story better than the spider story. In fact, several people mentioned they understood the spider bits more and needed all those words and details. Meanwhile, I am hardcore a believer of spec fic writers leaving most of the world-building in the filing cabinet at home. I way more enjoy being an involved, participatory reader and for the writer to honor my intelligence and imagination. But for those of you who need more detailed, direct writing, I see you. I can respect it.

That doesn’t mean I have to enjoy reading it.

There is also a difference between world-building and setting, which I have been thinking about a lot lately. World-building is the creation of a cohesive structure on which to hang a story. Creating a setting gives the reader’s imagination scenery in which to visualize the characters and actions. You see the difference? I can admit to using the two terms interchangeably at times, but some writers do one really well while doing the other horribly. Tchaikovsky does his darndest and really impresses with his world-building (especially with the spider planet and culture). He concentrates much less on setting, tone, individual scenes. As a reader, I am happier in a story that paints elaborate, vibey settings with few, very effective brushstrokes and honors things like spatial consistency, exterior mood-setting, and the mind’s eye (as well as impressive, poetic word-smithing). Tens—no, hundreds—of pages about dry spider history is never gonna do it for me. (I was literally rolling my eyes.) I do not like to be spoon-fed. But it does it for plenty of others.

The funny thing is that I almost (almost!) changed my tune by the time the audio book narrator wrapped this one up for me. Because the story overall and my enjoyment of the human part of the story had me actually enjoying the ending (which I did see coming but was still tense and exciting right up to the last moment). And I could appreciate the enormity of what Tchaikovsky accomplished here in pure scope, in innovative story-telling, in an enormous vision. And in those memorable scenes! I hadn’t thought of it along the way, but there are some scenes that are pure horror and they stick with you. There are also super fun moments that blow the lid off when it comes to cinematic storytelling. Honestly, I love stuff like that. But while I felt satisfied in the end, I have to be HONEST about my journey, which was an uphill one, many chapters a tramp through the never-ending mud.

I get it! I see you history of world wars. Slavery. I see you development through proto-humans. I see you patriarchy being shown to us flipped upside down as a matriarchy.

In the end, I couldn’t be as hard on it as I wanted to. I enjoyed the ending. I appreciated so much about it including its daring, its uniqueness, its epic moments/scenes, its sheer length of plot arc. How much others enjoyed it. If 200 words had been cut from the spider chapters and the POV and tone shifted so that it was more narrative, then it would have been a real win for me. It has been made clear to me that I would be one of the only ones celebrating these changes.

By the way, I heard that the series (Children of Time, Children of Ruin, Children of Memory) is connected unconventionally, like Ender’s Game and the Ender Quintet (or Saga). So they can each stand alone. I am happy, then, to leave this series here. It’s possible someone could talk me into reading more, but for now I am moving on to other books and series. I will for sure remember this one. I will remember what I admire about it, as well as what I slogged through. And I would be happy to recommend it to people who like this sort of thing, which are legion.

February 2, 2025

What to Read in February 2025

February is short and it has Valentines Day. I like to pull out a new romance to read in February. It can be contemporary, it can be a classic, it can be cross-genre. Here are some books I have read in previous years that I would recommend:

Jane Eyre

, Charlotte Bronte

Anna Karenina

, Leo Tolstoy

Pride and Prejudice

, Jane AustenEmma, Jane Austen

Sense and Sensibility

, Jane Austen

Northanger Abbey

, Jane Austen

Wuthering Heights

, Emily BronteRomeo and Juliet, William ShakespeareSonnets, Shakespeare

The Song of Achilles

, Madeline Miller

A Long Petal of the Sea

, Isabel AllendeSonnets from the Portuguese, Elizabeth Browning

The Princess Bride

, William Goldman

Love in the Time of Cholera

, Gabriel Garcia MarquezA Severe Mercy, Sheldon Van AukenA Midsummer Night’s Dream, William ShakespeareAnne of Green Gables, L. M. Montgomery (through the first three)

Rilla of Ingleside

, L. M. MontgomeryLes Miserables, Victor Hugo

Betting on You

, Lynn Painter

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

, Jenny Han

Book Lovers,

Beach Read

,

People We Meet on Vacation

, or

Happy Place

, Emily Henry

Little Women

, Louisa May Alcott

Universal Love

, Alexander WeinsteinStay with Me, Ayobami Adebayo

Normal People

, Sally Rooney

Fourth Wing

, Rebecca Yarros

If I See You Again Tomorrow

, Robbie Couch

Jane Eyre

, Charlotte Bronte

Anna Karenina

, Leo Tolstoy

Pride and Prejudice

, Jane AustenEmma, Jane Austen

Sense and Sensibility

, Jane Austen

Northanger Abbey

, Jane Austen

Wuthering Heights

, Emily BronteRomeo and Juliet, William ShakespeareSonnets, Shakespeare

The Song of Achilles

, Madeline Miller

A Long Petal of the Sea

, Isabel AllendeSonnets from the Portuguese, Elizabeth Browning

The Princess Bride

, William Goldman

Love in the Time of Cholera

, Gabriel Garcia MarquezA Severe Mercy, Sheldon Van AukenA Midsummer Night’s Dream, William ShakespeareAnne of Green Gables, L. M. Montgomery (through the first three)

Rilla of Ingleside

, L. M. MontgomeryLes Miserables, Victor Hugo

Betting on You

, Lynn Painter

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

, Jenny Han

Book Lovers,

Beach Read

,

People We Meet on Vacation

, or

Happy Place

, Emily Henry

Little Women

, Louisa May Alcott

Universal Love

, Alexander WeinsteinStay with Me, Ayobami Adebayo

Normal People

, Sally Rooney

Fourth Wing

, Rebecca Yarros

If I See You Again Tomorrow

, Robbie CouchI noticed that I have read a lot of unconventional or anti-love stories this year. If that is your jam for Valentines, then here are a few of those:

The Marriage Portrait

, Maggie O’Farrell (Yeah, it doesn’t turn out too well for this princess)

Miss Iceland

, Audur Ava Olafsdottir (the real love here is between friends)The Vegetarian, Han Kang (a book about isolation, with failed love at every turn)

The Marriage Portrait

, Maggie O’Farrell (Yeah, it doesn’t turn out too well for this princess)

Miss Iceland

, Audur Ava Olafsdottir (the real love here is between friends)The Vegetarian, Han Kang (a book about isolation, with failed love at every turn)

As for Valentines-appropriate books that I haven’t yet read but would like to:

Me Before You, Jojo MoyesAristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, Benjamin Alire SaenzEleanor & Park, Rainbow RowellFunny Story, Emily HenryThe Love Hypothesis, Ali HazelwoodThe Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, Victoria E. SchwabLove, Theoretically, Ali HazlewoodACOTAR series, Sarah J. MaasIron Flame and Onyx Storm, Rebecca YarrosBetter than the Movies, Lynn PainterHeartstopper series, Alice OsemanDivine Rivals, Rebecca RossLegends & Lattes, Travis BaldreeNorth and South, Elizabeth GaskellThe Thornbirds, Colleen McCulloughRed, White & Royal Blue, Casey McQuinstonOn Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean VuongEverything I Know About Love, Dolly AldertonImogen, Obviously, Becky Albertalli

Me Before You, Jojo MoyesAristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, Benjamin Alire SaenzEleanor & Park, Rainbow RowellFunny Story, Emily HenryThe Love Hypothesis, Ali HazelwoodThe Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, Victoria E. SchwabLove, Theoretically, Ali HazlewoodACOTAR series, Sarah J. MaasIron Flame and Onyx Storm, Rebecca YarrosBetter than the Movies, Lynn PainterHeartstopper series, Alice OsemanDivine Rivals, Rebecca RossLegends & Lattes, Travis BaldreeNorth and South, Elizabeth GaskellThe Thornbirds, Colleen McCulloughRed, White & Royal Blue, Casey McQuinstonOn Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean VuongEverything I Know About Love, Dolly AldertonImogen, Obviously, Becky AlbertalliBooks that are being published in February that the experts (and fans) tell us we should be excited about:

Three Days in June, Anne TylerWe All Live Here, Jojo MoyesFamous Last Words, Gillian McAllisterThe Queens of Crime, Marie BenedictYou Are Fatally Invited, Andre PliegoBlack Woods, Blue Sky, Eowyn IveyListen to Your Sister, Nina VielSomething in the Walls, Daisy PearceDeep End, Ali HazlewoodScythe & Sparrow, Brynne WeaverNeedy Little Things, Channelle DesamoursRebel Witch, Kristin CiccarelliMemorial Days: A Memoir, Geraldine BrooksCleavage, Jennifer Finney BoylanSource Code, Bill GatesThe Bones Beneath My Skin, TJ KluneStone Yard Devotional, Charlotte WoodBooster Shots, Adam RatnerNothing Serious, Emily J. SmithAir-Borne, Carl ZimmerBibliophobia, Sarah ChihayaVictorian Psycho, Virginia FeitoPure Innocent Fun, Ira Madison IIINesting, Roisin O’Donnell

Three Days in June, Anne TylerWe All Live Here, Jojo MoyesFamous Last Words, Gillian McAllisterThe Queens of Crime, Marie BenedictYou Are Fatally Invited, Andre PliegoBlack Woods, Blue Sky, Eowyn IveyListen to Your Sister, Nina VielSomething in the Walls, Daisy PearceDeep End, Ali HazlewoodScythe & Sparrow, Brynne WeaverNeedy Little Things, Channelle DesamoursRebel Witch, Kristin CiccarelliMemorial Days: A Memoir, Geraldine BrooksCleavage, Jennifer Finney BoylanSource Code, Bill GatesThe Bones Beneath My Skin, TJ KluneStone Yard Devotional, Charlotte WoodBooster Shots, Adam RatnerNothing Serious, Emily J. SmithAir-Borne, Carl ZimmerBibliophobia, Sarah ChihayaVictorian Psycho, Virginia FeitoPure Innocent Fun, Ira Madison IIINesting, Roisin O’Donnell

I also want to mention a book that was published in 2023, but has sprung to the top of the bestsellers lists. Why? It is by Mariann Edgar Budde, the bishop who delivered the homily for the inauguration a couple weeks back and confronted President Trump by asking for mercy for scared Americans and immigrants. Her third book, which is the one trending, is crazily (I mean appropriately) enough about being brave and is titled How We Learn to Be Brave. You may find it back-ordered, right now, but I’m sure the publishers are getting right on that.

Like everything I read last month is recommendable, though I certainly enjoyed some reads more than others. The only book I would not recommend, I am not even going to review because it is self-pubbed. Let’s forget that ever happened.

Scythe

(Arc of a Scythe #1), Neal Shusterman

Miss Iceland

, Audur Ava OlafsdottirChildren of Time, Adrian Tchaikovsky (if you are that sci-fi type)Lucky Jim, Kingsley Amis (if you are an older Anglophile)The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain (if you are insistent on classics)James, Percival Everett

Scythe

(Arc of a Scythe #1), Neal Shusterman

Miss Iceland

, Audur Ava OlafsdottirChildren of Time, Adrian Tchaikovsky (if you are that sci-fi type)Lucky Jim, Kingsley Amis (if you are an older Anglophile)The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain (if you are insistent on classics)James, Percival Everett

The Vegetarian, Han KangBeasts of Prey (Beasts of Prey #1), Ayana GrayOrbital, Samantha HarveyThe Warden (The Warden #1), Daniel M. Ford

The Vegetarian, Han KangBeasts of Prey (Beasts of Prey #1), Ayana GrayOrbital, Samantha HarveyThe Warden (The Warden #1), Daniel M. FordI have crammed the February TBR full of other books, too. I will never get through these, but I have a system for carrying over so that I don’t feel too guilty about that.

Me Before You, Jojo MoyesThe Secret of the Tower, Andrew BeattieThe Angel Player, Andrew Beattie (ARC)Solito, Javier ZamoraJulie Chan Is Dead, Liann Zhang (ARC)Wicked, Gregory Maguire (finish)The Eyes and the Impossible, Dave EggersLove & Lemon’s Simple Feel Good FoodPainted Devils, Margaret OwenAristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, Benjamin Alire SaenzHold Me Closer, Necromancer, Lish McBrideBreakfast of Champions, Kurt VonnegutI Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie MooreA Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy TooleEleanor & Park, Rainbow RowellCreation Lake, Rachel KushnerChain-Gang Allstars, Nana Kwame Adjei-BrenyahRed, White and Royal Blue, Rajani LaRoccaPrayer, Timothy KellerADHD Is Awesome!, Penn and Kim Holderness (finish)Save the Cat! Writes a YA Novel, Jessica Brody (finish)

Me Before You, Jojo MoyesThe Secret of the Tower, Andrew BeattieThe Angel Player, Andrew Beattie (ARC)Solito, Javier ZamoraJulie Chan Is Dead, Liann Zhang (ARC)Wicked, Gregory Maguire (finish)The Eyes and the Impossible, Dave EggersLove & Lemon’s Simple Feel Good FoodPainted Devils, Margaret OwenAristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, Benjamin Alire SaenzHold Me Closer, Necromancer, Lish McBrideBreakfast of Champions, Kurt VonnegutI Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie MooreA Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy TooleEleanor & Park, Rainbow RowellCreation Lake, Rachel KushnerChain-Gang Allstars, Nana Kwame Adjei-BrenyahRed, White and Royal Blue, Rajani LaRoccaPrayer, Timothy KellerADHD Is Awesome!, Penn and Kim Holderness (finish)Save the Cat! Writes a YA Novel, Jessica Brody (finish)

February 1, 2025

Writer in the Wild: Jimmy Carter Wrote a Novel

I’m a few weeks slow on the upswing, but what a few weeks it has been! Yeah, I mean what you think I mean, but I also mean that everyone is sick with norovirus and RSV and pneumonia this January (including us with a stomach bug and flu) and I have a couple deadlines looming and I got a new parttime job. Which I already mentioned on the blog. I’m sure it’ll come up many more times. I am a part-time writer and part-time bookseller and this month has been bonkers.

I have never felt the whole “January is 572 days long” thing like I did this year.

Somewhere in there, Jimmy Carter died. Okay, technically he died on December 29th, but see? Doesn’t that seem like a world ago?

I met Jimmy Carter, way back in 2003. He had just become the first (and still only) president to have published a novel and was going to sign copies of The Hornet’s Nest at a local bookshop. From what I can tell, it was to be his only novel, though he wrote many nonfiction books, religious meditations, a nonfiction YA book (With Talking Peace), a book of poetry (Always a Reckoning), and even a children’s picture book, The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejur. There might have been more that I’m missing.

I’m a book nerd. I was fascinated with the idea of Carter being the first president to write a novel. I was a regular at the Regulator events at the time, and I bought my ticket and picked up my copy of the book. (Yes, the Regulator is where I work now, but this is less of a coincidence than that I still live in the same city.) On the day of, I remember standing in line up the block from the shop, the line stretching out far behind me. It was slow moving, and secret service dotted the path, some statuesque—refusing to engage even if you tried—and others repeating directions on how to behave in front of a former U.S. president. They told us to have our book ready, to step up to the table and say a quick greeting, to step to the side, to take back our book and get out quickly and calmly. No dawdling, No long conversations. No pictures. It was clear that anything construed as funny business would be cut short by one of those statues in a suit.

The table where Carter was signing books was through the upstairs of the shop, down the stairs and through the downstairs of the shop. The line snaked through the aisles and into what was probably still the cafe, though I don’t remember it being a cafe that day, so perhaps that was already gone. Unfortunately, as I stepped up and handed my book to an assistant, shivering with trepidation (because I’m worried I’ll do something wrong even when I have no history or intent of doing it), the guy in front of me insisted on not stepping to the side but engaging Carter longer, gaining him intervention from the secret service. Which means my encounter was cut short and edged in tension. Thanks, dude. But I did get my book signed, did technically meet Jimmy Carter.

As for The Hornet’s Nest, I read it. (Did I finish it?) Yes, I read the copy that was signed because while I value things like that, I am also practical to a fault and don’t hold many things as precious. It’s, ahem, not a literary marvel. About the Revolutionary War, it covers some aspects of the South that aren’t dealt with as much, like Native American involvement and families (here Northern transplants and Quakers) who do not want to fight the British. The history is well-researched. The writing is, well. He was used to writing history and memoir (which is essentially history). The book is fact-heavy and “dry.” But it still sits on my shelf and I imagine always will.

I don’t have many intelligent things to say about Carter. He was President when I was born, but I was unaware of it. I have heard commentary about him, and I admire the man that he was, at least as a post-president. However, this is a book blog, and I should probably stay in my own lane which is not political correspondent.

Here’s a nod of my head to Carter as he goes. Here are my condolences to his family and also a hurrah for a life well-lived. And here’s a brief mention of the only novel written by a U.S. president and the day I basically met another novelist who was also a world leader.

January 23, 2025

Book Review: Miss Iceland

The cover. That’s what a lot of reviews mention because, well, most people expected to read one kind of thing based on the cover and then got something else. Myself, I read Miss Iceland by Audur Ava Olafsdottir (ohd-thur ah-vah oh-lahfs-dah-tur—ish) because it was a book club read for one of the clubs I am committed to. And whatever I might have thought of the cover, I loved the book. When I waded in, for a while, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. But the further I went, the more I appreciated the writing style, the themes and characters, and, well, mostly the writing style and the cultural immersion.

Hekla was named after a volcano, and like the volcano, there are a lot of fiery depths under her usually calm surface. Hekla is a writer (aka poet), but it’s the 60s in Iceland and women aren’t allowed to be poets. Or make much money or have almost any job. Or walk down the street without being harassed (especially if you are as pretty as Hekla). So she moves to the city to write in secret. On one side of her is her best girlfriend, Isey, who got knocked up young and is trapped in a marriage that is doomed to produce many children, the stuff of her nightmares. On the other side of Hekla is Jon John, a gay man in 60s Iceland which is much worse even than being a woman. It’s more dangerous and deadly, too. How will any of these young dreamers survive their reality?

I was much more into this book than others I’ve read recently. The style is clear (although our relationship to the characters feels a bit wooly at times), clean and spare, literary and Icelandic-poetic (as far as I know). The narration is broken into tiny fragments and evolves until, by the end, it is almost poetry. I learned a lot while reading about the culture (in the 60s, anyhow), the food, etc., but also realized this is a culture I don’t know enough about to appreciate its literature in too much depth. The story is very tactile. Very moving. But also pretty hard: the way Hekla is treated in the 60s in Iceland as a woman is truly appalling and disturbing, and likewise the way that a gay man is treated in the 60s in Iceland it actually horrific. I was sick to my stomach a couple times.

a more appropriate cover for the Icelandic edition

a more appropriate cover for the Icelandic editionI give it five stars. It’s literary, poetic, dysthymic, maybe bohemian. It’s also brutal in some ways, redemptive and beautiful in others. So many sacrifices must be made for the dream, even the dream of an average life. It’s difficult to describe this book. It’s also difficult to express what I like so much about it.

Here’s something interesting: out of a group of like 15 to 18 people at club, two people emphatically did not like this book. The rest of the group emphatically defended it. It actually felt like we were talking about two different books. So perhaps once in a while in a group of literary readers, you get a couple people who just don’t connect to this book in any way, just don’t get it. The rest of us will die on this hill.

Ya know, I have thought some about these two (ladies, one middle-aged and one older than that), and I think it is possible that the changes in perspective in literature over the past couple (few?) decades might be where they are missing the point of the book. They both kept saying that Hekla was “complaining” and that she was “self-absorbed” (and also pointless and obvious?) to which the rest of us responded with slack jaws. But this makes some sense if you think about third person omniscient (the POV of most of the stories through time) and first person, often present tense (the favorite POV of younger people who are incidentally getting older). If you are a reader who has not yet adjusted to this new-fangled POV, the perspective itself could cause you to hear the voice of the author and/or protagonist as complaining and self-absorbed. I think I’m on to something there.

Not that authors weren’t doing stream-of-consciousness long before now. Which is sorta what this book is.

But let’s move on. This is a translation. It was published in Icelandic in 2018, the English translation in 2020. As far as I can tell, it’s a beautiful translation, one that somehow retained the cadences of the language so well that I had the Swedish chef from the Muppet’s in my head between reading sessions. (Yes, Icelandic and Swedish are not the same, but they are more similar than Icelandic and American English.) The translation that we have available in the US at this point—the one that I read—is actually a British English translation, so there are two levels of translation happening. And yet…

Like Lisa (NY) from Goodreads said, “This slim, melancholic novel set in 1960s Iceland has lodged under my skin.” Yes, Lisa. Correct.

I’m with the reviewers who don’t think Hekla’s boyfriend was the scum of the earth. He was sucky a little, a product of his times, but he changed some, too. And Hekla was sucky sometimes, as well. She used him. She left him high and dry.

The ending is also controversial. I thought it appropriate, satisfying if a little bitter, a little sad.

Besides all the food that is mentioned in this poetic novel (and beware: much of the food sounds not so wonderful to us Americans), there are so many book titles and authors thrown around. For funsies, here is a list of the ones that I caught: