Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 8

September 16, 2024

Book Review: A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking

Baking and fantasy as written by T. Kingfisher? Of course! YA. Fairy tale-style. Funny. Charming. All that. But it is Kingfisher, so there are also dead bodies strewn along the story’s path, and some scary moments, just more funny, coming-of-age things than the bodies and scares. It gets wacky. It gets introspective. And it’s written clearly. It’s a fun book for any (especially teen and tween) fan of the fable end of fantasy. And giggling.

Mona is a wizard, but let’s face it, she doesn’t have a cool or powerful form of magic. I mean, her power is bread. But she’s happy baking all day in her aunt’s and uncle’s bakery. Or she was. And then a body appeared on the floor of the kitchen and she was arrested and taken before the Duchess, throwing her head-first into a situation that includes a serial killer, the marginalizing of magical people, and a sudden need for the city to have twelve-foot-tall gingerbread defenders. Now she’ll be happy if she can survive till her fifteenth birthday.

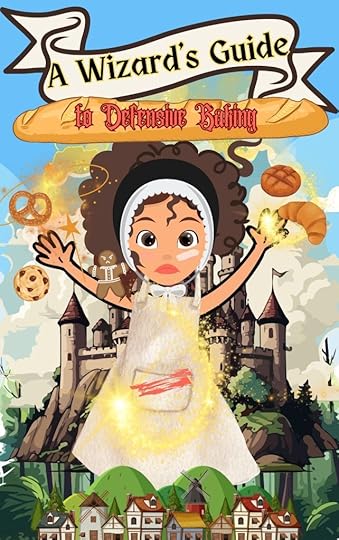

I am a T. Kingfisher fan. I am not a fan of this cover, though. I was already kind of upset with the title, because I read cookbooks and this novel doesn’t even include recipes. But it sounds like it should. The novel is not a guide. Period. And then the cover is boring, not really indicative of anything. I made a quick cover for you on Canva. It’s pretty bad, I know, but it does give you some sense of what this book is about. If only the publisher had gone in that sort of direction…

I actually don’t have much to say here. It’s just a solid book and a fun read. If you like magical, fairytale-esque stories with teenage girl baker protagonists, then absolutely. Go for it. As I already said, it’s funny and our protagonist is growing and figuring out the world while some crazy stuff is happening to her. I guess I might complain a little bit about the pacing and the happening to Mona as opposed to her doing something. Also, I wish Kingfisher would describe more regarding her characters and settings, which is a preference thing I guess but I’m over not having something to go on with characters. Still, I think you’ll enjoy this book, especially if you enjoy a wild imagination and a generous dose of quirk. And if you’re not a total dud yourself.

See HERE for a very short bio in a previous review.

Also, I was able to see her in person again this past week. She participated on an author panel/for an author reading and Q&A, and I once again enjoyed hearing her. Then I met her and had her sign some books. Again, I find her really approachable and cool.

“’You didn’t fail,’ I said. ‘They wouldn’t let you succeed. It’s different” (p204).

“I mean, here I was, trying to save the city from being overrun by cannibal mercenaries, and I felt sick to my stomach because the cook was mad at me. Being fourteen has a lot of drawbacks” (p215).

First Line: The Ministry of Time

“Perhaps he’ll die this time. He finds this doesn’t worry him. Maybe because he’s so cold he has a drunkard’s grip on his mind. When thoughts come, they’re translucent, free-swimming medusae.” First lines of The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley. And I was hooked on her voice from the very beginning.

Book Review: Martyr!

I would recommend that if you haven’t already, don’t read the synopses (at least the one on Goodreads) for Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar. There is just one line of explanation that—if you are very observant and have a good memory—could destroy your experience of the book. Because there is a twist of sorts, and the synopsis needlessly drops a giant clue that is not in the book until much, much later. And now that I have warned you (it seems prudent to put that first), I will share that this book is a recommend from me to you (if you like literary fiction) and also that I am glad I read it. It’s a well-written, interesting book.

Cyrus Shams might have been born in Iran, but he was raised in the Midwest. After losing his mother in an “accidental” airplane incident in Tehran, his father works in a chicken factory in Indiana and disappears into the bottle. Cyrus grows to be an alcoholic and addict himself, as well as a poet obsessed with the ideas of martyrdom and how a life—and death—might have meaning. When a friend mentions an art exhibit in Brooklyn, Cyrus (newly sober and newly orphaned) can’t resist checking it out: a successful painter has terminal cancer and has made herself into her final show.

I read this book because it was a book club read, but I was unable to go to the club where it was discussed. I was glad that I read it, anyway, but I won’t really have any other opinions or the group consensus to share with you. It seemed like it would be a good book. (Either that, or that it would be pretentious and overwrought.) It was a good book. I enjoyed it (which is probably not the right word because the topics are heavy and none of them super cheery).

Let’s first address the structure of the book. I have shared many times before that I like to know the structure ahead of my read, and Martyr! has some different things going on. First of all, though the book is about Cyrus, his is not the only POV in the book. Most notably, there are chapters told from his mom’s perspective. (There are other POVs, too.) Which would lead to our next point about structure: there are significant bits of flashback. There are also short entries from Cyrus’s computer files notes/drafts of his Book of Martyrs. And there are dream sequences which are conversations between people in Cyrus’s life (they are Cyrus’s dreams) and famous people (sometimes even cartoons). But with all this going on, there is a “present” timeline that takes Cyrus from his apartment with his BFF Zee, to Brooklyn and the art exhibit. The flashbacks, different POVs, poems, and dream sequences serve to flesh the plot and characters out.

There are many themes in this book. Maybe it’s dealing with too many, I dunno, but the reader is able to follow all of them. Some of the main themes are martyrdom (life/death/suicide), poetry (and art), alcoholism and addiction (and sobriety), the American immigrant experience (specifically Persian), sexuality, and parents/parenthood. More generally, I guess we’re talking about love and death or love and life. The book is a little more dysthymic than I would normally like. It is also grittier than I usually like. With perhaps too-graphic sex and some of that trendy-trippy drug stuff going on. However, I bought into the whole package here, as it was balanced with levity, imagination, literary play, deep contemplation, and great writing.

Let’s talk about the writing. There is some connection here to Tommy Orange (author of There, There and Wandering Stars). In fact, Akbar and Orange are friends who “riff” off each other and call it “the band.” When I saw that Orange had anything to do with Akbar, unfortunately, I was like—big sign—it’s going to be one of those sorts of books. (Like super-lauded but, for me, ultimately disappointing.) In the end, I think Martyr! only comes off better for a comparison to Tommy Orange’s works. Their works do have things in common. But I was so much more into Akbar’s writing. It could be because he is really a poet. (He says his first attempt at this novel was a mess and that Lauren Groff “ripped it” apart and helped him figure it out.) His writing is melodious and full of fascinating twists of language, but he also has so much to say. (I underlined a ridiculous amount of quotables.) And in the end, though less straight-forward and more literary and experimental than popular fiction, the poet Akbar pulled it off in a smooth, cohesive, story-telling-adjacent way. So thanks to Groff, I guess.

But we do have to talk about the actual end, as in the book’s ending. I don’t want to get into spoilers, but there are some things that I did see coming too early. And ultimately the ending is ambiguous. As in, you could read this book and your husband could read this book and you could spend hours or days trying to convince each other that this is what happened at the end and laying out all your evidence over and over and there would be no decisive conclusion. So, if you are either a) okay with ambiguous endings or b) so sure of yourself that you can always pick one version and be confident about your decision/reading, then you should still read this book. If you hate ambiguous endings, then you have been warned.

There is a lot of food mentioned in this book. It would be easy to cook to go along with your book club meeting.

Martyr! is a somewhat gritty, trippy, dysthymic, novel that has things to say and to explore but also—to a lesser extent than some—has an actual story. And an ambiguous ending. It’s a real Persian culture-American youth mash-up which I found exciting to read and would be happy to sit around and discuss with a book club or a class or just a friend. I found the writing both approachable and beautiful and though it took me a second to orient myself in the book, I appreciated the alternative structure, the different POVs, the fun dream sequences, and even the times it may or may not be magic realism. I’d say that it’s a real bittersweet book, both tender and sentimental as well as bitter and disappointed. (Not disappointing, but disappointed.) I look forward to Akbar’s next novel, assuming there will be one.

This is Akbar’s debut novel. He is firstly a poet and he has a chapbook and two books of poetry available and has done really well for himself in that world. His poems have been in all the most exclusive places and he’s had a few impressive editing gigs. Awards, too, including the Pushcart. Martyr! is based somewhat on his own life, but it is still a novel. He’s an editor and professor in Iowa.

Books of poetry:

Pilgrim BellCalling a Wolf a WolfPortrait of the AlcoholicBooks he’s edited:

Another Last Call: Poems on Addiction & DeliveranceThe Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 100 Poets on the Divine

“A drunk horse thief who stops drinking is just a sober horse thief, Cyrus’d said, feeling proud to have thought it. He’d use versions of that line later in two different poems. / ‘But you’re not a bad person trying to be good, You’re a sick person trying to get well,’ Gabe responded” (p13).

“That was the clarity, alcohol, and nothing else, gave. Seeing life as everyone else did, as a place that could accommodate you. But of course a second later it’d zoom past clarity through a flurry of increasingly opaque lenses until all you were able to see would be the dark of your own skull” (p15).

“Cyrus wanted to kick him in the face. For being racist. For being a little right. / ‘I’m not trying to be an asshole,’ Gabe said, his voice softening. ‘But it’s a schtick. It’s a schtick and it’s holding back your recovery. And your art’” (p26).

“What do you, specifically, want from your unprecedented, never-to-be-repeated existence? What makes you actually different from everyone else?” (p27).

“Do you know what the first rule of playwriting is? …. You never send a character onstage without knowing what they want” (p27).

“I’m not uncomfortable sitting in uncertainty. I’m not groping desperately to resolve it. I got four DUIs in a month because I was certain I was in control” (p28).

“’Asking what?’ Curis asked. ‘What were we even talking to?’ / ‘Who cares?’ Gabe answered. ‘To not-your-massive-f*ing-ego’” (p28).

“It was soothing, to stop time and reword memory, imagining through the thesaurus multiverse” (p29).

“Being awake was a kind of poison, and dream was the only antidote. What if everyone was more conscious of this? How would it charge, make more urgent, their living? ‘I have been poisoned, I have only sixteen hours until I succumb’” (p33).

“He hated having to convince people he was both sufficiently immobilized by despair and also doing okay enough to take care of himself and his son” (p37).

“The Shams men began their lives in America awake, unnaturally alert, like two windows the the blinds torn off” (p38).

“When people travel to the past, they do it with this wild sense of self-importance. Like, ‘gosh, I better not step on that flower or my grandfather will never be born.’ But in the present we mow our lawns and poison ants and skip parties and miss birthdays all the time. We never think about the effects of that stuff… Nobody things of now as the future past” (p59).

“Every tiny decision becomes mired with importance, and we’re immobilized” (p59).

“But Cyrus was, for the most part, more than a little surprised by the words as they came out of his mouth, how they gave shape to something that had long been formless with him. It was like the language in the air that night was a mold he was pouring around his curiosity. Flour thrown on a ghost” (p75).

“For all our advances in science—chickens that can go from egg to harvest in a month, planes to cross the world, missiles to shoot them down—we’ve always held the same obnoxious, rotten souls. Souls that have festered for millennia while science grew” (p111).

“You wrote a fact in a book and there it sat until someone born five hundred years later improved it. Refined it, implemented it more usefully. Easy. You couldn’t fo that with soul-learning. We all started from zero. From less than zero, actually. We started whiny, without grace. Obsessed only with our own needing. And the dead couldn’t teach us anything about that” (p111).

“…but there was no ethical consumption under late capitalism and sometimes, Cyrus figured, one had to pick one’s battles. He tried not to think too much about these contradictions” (p112).

“We invented it, this language where one man is called Iraqi and one man is called Iranian and so they kill each other. Where one man is called an officer so he sends other men, with heads and hearts the size of his own, to split their stomachs open over barbed wire. Because of language, this sounds stands for this thing, that sounds stands for that thing, all these invented sounds strutting around, certain as roosters. It is no wonder we got it so wrong” (p125).

“But I thought it lucky, the clarity of tears. Instead of the loose riot of confusion and dread webbed up in my chest, in my head, probably wearing lesions in my gut and brain” (p126).

“Cyrus could see it in their chests when they looked at him. It was like Americans had another organ for it, that hate-fear. It pulsed out of their chests like a second heart” (p133).

“The iron law of sobriety, with apologies to Leo Tolstoy: the stories of addicts are all alike; but each person gets sober their own way” (p144).

“Active addiction is an algorithm, a crushing sameness. The story is what comes after” (p144).

“In the back of your brain, your addiction is doing push-ups, getting stronger, just waiting for you to slip up, an old-timer had once told him” (p155).

“That people found the surplus psychic bandwidth to consider—or even worry over—anyone else’s interior seemed a bit of an unheralded miracle” (p176).

“…he was always feeling anxious, anxious about his place in the world, his relative goodness or inescapable selfishness” (p178).

“It seems very American to expect grief to change something. Like a token you cash in” (p183).

“The language will never be the thing. So it’s damned, right? And I am too, for giving my life over to it” (p185).

“A photograph can say, ‘This is what it was.’ Language can only say, ‘This is what it was like’” (p199).

“It was excruciating, now, for Cyrus to think of himself as the unwitting subject of the same predictable psychic tempests as ever other human on the planet” (p207).

“Cyrus thought about what an aggressively human leader on earth might look like. One who, instead of defending decades-old obviously wrong positions, said, ‘Well, of course I changed my mind. I was presented with new information, that’s the definition of critical thinking’” (p208).

“Everyone in America seemed to be afraid and hurting and angry, starving for a fight they could win. And more than that even, they seemed certain their natural state was to be happy, contented, and rich” (p209).

“See, this is why everyone should just do what I do,’ Zee said. ‘Be right about everything, and shut up about it’” (p218).

“It was one of those billion little sacrifices a parent makes that a child never considers. The kind, Ali thought, only the worst, most loathsome parents ever mentioned” (p251).

“Eight of the ten commandments are about what thou shalt not. But you can live a whole life not doing ano of that stuff and still avoid doing any good” (p270).

“I want to be the chisel, not the David. What can I make of being here? What can I make of not?” (p270).

“For a drunk, there’s nothing but drink” (p271).

“If you’ve moved through the world in such a way as to feel you’ve earned some cosmic compensation, then what you’ve earned is something more like justice, like propriety. Not grace” (p279).

“There’s no meeting someone once they’ve been plucked from living. You just live with their absence, whispering ‘jaya shomah khallee’ to a chair on which they might sit, a second unused pillow on the bed” (p280).

“’…please’ and ‘sorry’ and ‘thank you’—all you need in any language, really, unless you’re a philosopher” (p281).

“But these lovers didn’t lack the ability to perceive my desires. They lacked faith in my conviction” (p283).

“It happened like it does for anyone, fame. Bullshit luck disguised as a lifetime of hard work. But also vice versa” (p287).

“I resented work for this reason more than any other. The countless paintings that would never exist because I had to be working for money instead of painting. I resented my body for the same reasons, its ravenous gobbling up of time, its constant calibrations, needing to eat, shit, smoke” (p291).

“All of us were dying, I’d remind them. I was just dying faster” (p292).

“’Listen to me. You are not the patient today’ …. It’s a good day when you’re not the patient” (p299).

“Anger is a kind of fear. And fear saved you. When the world was all kneecaps and corners of coffee tables, fear kept you safe” (p302).

“You can put a saddle on anger, Cyrus” (302).

“How when he saw a bird or a tree or a bug, Zee really saw that bird or tree or bug, not the idea of it. How he really saw Cyrus, really heard him, beneath all his beneaths” (p320).

September 11, 2024

Play Review: Twelfth Night with Multiple Bonus Reviews

Apparently, one of the book clubs I am a part of reads Shakespeare in August—like for the past 17 years. It’s not the club I would have expected it of, exactly, but I was excited. I am a Shakespeare fan and have been since high school. Another thing: they bring in this Renaissance Literature expert/professor from UNC who is the son of one of the club’s founding members, so it’s this big tradition with a totally different tone, more educational. I didn’t know all this ahead of arriving at club, but boy would that have excited me, too. I love learning. Happily a life-long learner.

Viola and Sebastian, twin siblings, have been separated by shipwreck. Alone on a strange shore, Viola assumes her brother is dead and looks for a place to safely settle, which she deems most likely if she poses as a boy and becomes a consort of the local Duke. Currently, the Duke is pining away for the love of Olivia, a woman who is also mourning a lost brother and won’t give the Duke the time of day. But if the Duke sends his new companion (Viola posing as Cesario) to woo Olivia on his behalf, of course Oliviawill see sense and marry him! A subplot, wild antics, meaningful asides, and crossed loves (and genders) abound. And a sword fight. And dancing. And drunkenness. And co-weddings.

This August at book club was, as the title indicates, the reading of Twelfth Night. I do not believe I had read this Shakesperean play before, though I had a vague idea of it as a girl-dressing-up-as-boy thing. True to character, I went a little deep. I read the book (in my leather-bound complete collection), I studied it using outside sources, I watched the “best” movie adaptation, and I watched a silly, modern movie adaptation. Then while at the bookstore waiting for club to begin, I wandered past the new YA recommendations bookshelf and, lo and behold, face-forward was Twelfth Knight, a modern YA adaptation. I bought it. Then I read it, too.

I don’t know how much I can say bad about Shakespeare. He is the master. But Twelfth Night was not my favorite. It’s not the language that is lacking—or a lack of bawdy innuendos and cultural jokes—but the plot and the characters. And it’s not all bad; there are just a few missteps, I think, that make it not as satisfying as other Shakespearean plays. Of course, it’s always hard to judge a piece of literature (in this case a play) this old, and it’s almost impossible to meet it on its own terms, but despite the gender-bending and homosexual undertones (which I actually think are not there in the original but I can see why people read them in today, what with our utter lack of deep, even physical, platonic, same-sex friendships in our own time and place), I find that the jokes, plot, and portrayal of the characters don’t translate super well to modern times. Perhaps there’s too much of specific politics and cultural satire for us to catch? Or we just feel kinda different about the world at this point. Or the madcap dash to shoehorn in marriages (which works so well in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Much Ado About Nothing) seems both too over-the-top, too unpredicted, and also tinged with the tragedy of one storyline, to appeal to our sensibilities. I’m no expert.

Our group was led by Dr. Reid Barbour, the UNC Chapel Hill prof. He told us that we have audience response to the play as far back as its first release (in something like 1601), written down by a John Manningham. Then he went on to commiserate about the play Socratic-style, asking us probing questions, herding us gently into considering, nay mining our reading for what we really had found there. He considered the theme to be: Is it okay to disguise yourself? Related to hypocrisy. Related to the ethics of lying. When you put it that way, how could this not translate for all time?

One of the problems with Twelfth Night is a practical joke gone wrong. Admittedly, I was put off by it, kinda disgusted, even though we were supposed to dislike the character that is being pranked—and I did. But… Not everyone felt conflicted. Either way, when there is a sudden marriage for two of the involved characters doled out at the same time the pranked character’s pledging revenge… it’s awk-ward. Not mirthful. Not playful. Maybe disturbing. As Barbour said, “The world can be very hostile and tragic. The framing is death.”

Perhaps one of the most important things to know when approaching this play—aside from the political and religious factoids Barbour threw at us (including usage of the word Puritanical at this point in history—look it up)—is an understanding of the holiday Twelfth Night in Renaissance England. It was a topsy-turvy day (made me think of Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame’s portrayal and song for the Feast of Fools, clearly) when rule-breaking was not only allowed but encouraged and celebrated. Anything goes! (At least for some people.) One of the traditional expressions of this was gender-swapping. Also feasting. Drinking. Etc.

I mean, most of the funny characters in this play—and Shakespeare’s plays all have their comic relief characters, not just the comedies like this one—are drunks with a darker side. Yikes. One of the characters’ arcs (Maria) makes almost no sense—or at least it doesn’t sell. Personally, I was confused about the social strata here. Though we see hierarchy and it’s important to the story, some of the main characters appeared to be neither lord and lady nor peasantry. They would need to be both to make all the plot points stick, so…

In the end, this play—originally titled “What You Will”—gave the audience what it willed, as far as I could tell. The immediate references. Haughty characters from society brought low. Those bawdy jokes. Easy laughs, all around. Things to know that the characters didn’t, leading to so much dramatic irony. Dramatic irony coming out our ears! Morally fringe behavior. And, what they will: a manic-hysterical finale with a happy ending. (Is Shakespeare toying with the audience here? Is he messing with the play just to say something about plays, comedies, and audiences in general? We may never know. Well, we won’t know. We’ll have to make an educated guess.) And I found it useful to think of it as a play with substitutions as opposed to one with meaningful relationships. In other words, people had needs and desires and were basically selfish, so it didn’t really matter who filled those needs and desires, in the end. (Though Barbour also thinks the play might be about just getting through the day.) Also, reunited families are super-important to Shakespeare in his works, so maybe he was just determined to reunite and unite the families, come hell or high water. Maybe order matters, and family is the epitome of order.

As with any Shakespeare, we end up asking ourselves, was the Bard writing a thesis or was he just making a buck? Another thing we’ll never really know.

THE SHAKESPEARE BOOK

I had my eye on a few Shakespeare reference books for quite some time. (I told you, I’m a fan.) Since I didn’t have any prior interaction with Twelfth Night, I went ahead and ordered DK Publishing’s The Shakespeare Book from their Big Ideas Simply Explained series. Twelfth Night is covered in six pages with a few small illustrations, a timeline, and a character-relationship map. While interesting and a good coffee table book (in a writer’s house, at least), it’s not the most thorough or even thoughtful book. That does not mean I won’t be referencing it in the future. I will be referencing it in the future. For one thing, it gives enough of the basics to put the play in context and help a reader know what to expect, how to read it, basically. And it has some fun factoids too.

It’s a light, useful book to get your bearings with any Shakespeare play. Is it Shakespeare? (Haha.) No. Is it on the grad-student level? Not even in the same ballpark. But it is essentially a For Dummies book and I’ll be hanging on to it. It would be real nice sitting on the shelf in a classroom full of highschoolers or maybe even middle schoolers. There’s no direct translations or detailed information, but it also has an introduction with general information and section introductions talking about each stage of Shakespeare’s life. A decent jumping-off point or, if you aren’t a big Shakespeare fan, a way to work out some of the basic facts and meaning for, say, a test or a book club.

TWLEFTH NIGHT (BBC 1996)

I’m going to sandwich a movie review in here between the book reviews, because the 1996 BBC movie adaptation has more in common with the play than anything that follows. I looked it up, and this is the presentation universally deemed the “best.” And I was very glad I watched it: it really helped me to understand what was going on in the play, which it followed pretty closely except for at the beginning. When I returned to the text, however, some of the actors—okay, maybe all of them—stuck with me. I couldn’t put new, imagined characters in their place.

As a movie by itself, it was pretty good, full of British actors that I recognize (like Olivia Bonham Carter, Ben Kingsley, and Imelda Staunton). It slimmed down the story quite a bit but kept the language, but the real problem was that actually seeing an actor and actress play the twins here, in HD, made the plot ridiculous. There is just no way one could be confused for the other. Which is what I had been thinking when I was reading the play. (I was told, though, that the 1980 version has a pair of actor-actress that is actually very convincing. I’ll believe it when I see it.) Also, there was an intro added to the movie that presented the twins in a career and position that made my confusion about their social status from the original play much exacerbated. They were trying to foreshadow the gender-games that would ensue and introduce comedy early (and even put a play within a play and roles within roles; how meta), but it was confusing to the plot, for sure.

I would definitely recommend it as far as complementing and understanding the play, though. Plus with the right test questions it will weed out the students who didn’t actually read the play.

TWELFTH KNIGHT

I mentioned above that I picked up a modern retelling of Twelfth Night from the YA section of my bookstore, and that would be Twelfth Knight by Alexene Farol Follmuth. Follmuth is actually the author who brought us Atlas Six (a series I have not yet started), but this is the pen name she adopted for use with her younger-audience books. (Her other name is Olivia Blake.) T. Kingfisher did it. (Ursula Vernon). I have one. (Hazel Bean.) In theory, you can’t really compare the books across those names because writing for kids and adults can be reeeeeally different. But for what it’s worth, Twelfth Knight, published only this past May, has better reviews that the popular Atlas Six series. And it’s been backed by Reese’s Book Club.

And the spine on mine cracked and broke while I was halfway into it. Wuuuuut?

Anyhoo.

Viola is sick and tired of being a girl in a man’s world. Specifically, she’s sick of being dismissed by all the guys in her roleplaying club and being harassed by all the guys on her favorite multiplayer game. Her only option? Get mad at the world and pretend to be a dude as much as possible. But when the school jock is put out of commission for a season during a football play, Viola finds herself spending a lot of time with him in and out of the online realm, only Jack doesn’t know that she is the he he has befriended online. This could get awkward. It could get nasty. It could even break someone’s heart.

With a Reese’s Book Club sticker on it, I thought it couldn’t be terrible and it would be fun to have one more go-round with Twelfth Night before putting it to bed. Not a fan of the cover, but I dug in.

I read plenty of YA these days. YA can be for adults. But it’s usually meant for teens and perhaps early twenties peeps. This is really a high school-audience book, pretty light and self-exploratory, integrating some society critique and zooming in real close to the MC. It does really have vibes that are similar to the rom coms of the 90s, but it’s much more modern in its language and approach. And all the gaming. So much gaming.

It is probably best if you know that this book is really heavy on some of the hobby stuff. If you have zero interest in role-playing, RPGs, Renaissance festivals, and multiplayer games, then there might be some challenges for you here. Then again, an interest in high school stories and enemies to friends/nerd+jock romances might just carry you through. I am about 100 miles away from video games (personally. My son and husband play), but I do love cos-play, so there was some crossover for me. I might have even learned a thing or two, especially concerning terminology, but I also might have forgotten it all the second I put the book down. What I didn’t forget was the story or the characters.

I did enjoy this book. I would recommend it for YA readers, especially actual highschoolers. (There were phrases and words that I legit didn’t even know what they meant (even with teen kids) because it is written much younger than 45.) There’s “Game On” written on the side of the pages. (A little goofy, I thought.) There’s texting in the text. And while I would say Vi is the protagonist, we get the POV of both she and Jack. There is plenty of feminism going on here, but thankfully we didn’t go to the angry feminist, anti-relationship place that I was afraid for awhile we might. I mean, Vi might have, but Follmuth wrapped it up better than I had hoped. I appreciate dealing with feminine anger, by which I just mean anger in someone who is female. It’s an underrepresented reality and, when it is handled, is often done with too-broad strokes that further stereotypes and unrealistic expectations.

So yeah, I enjoyed it. A fun read. I was rooting for Vi and Jack. The writing was decent, clear. There might have been some things with the ending—or the plot in general—and also some side characters and general prose issues that I would have tightened up, but for a just-pulled-off-the-shelf-on-a-whim? Good times.

How did it compare with the original? Was it a faithful adaptation? I would definitely encourage a high schooler reading Twelfth Night to also read this, but it was certainly not a one-for-one kind of thing. The names are there, including the names of the high schools and even other places that got other Shakespeare names (like Verona). But otherwise, this is a very loose adaptation meant more to have fun than to make the original material approachable or even relevant. It had much more in common with the movie adaptation She’s the Man, but we’ll talk about that in three, two…

SHE’S THE MAN (2006)

Was it awesome? Or was it terrible? Is it a cult classic? Or is it a ridiculous flop? Both, really. Which means you’ll probably love it or hate it. Then again, I simply couldn’t make up my mind. One minute I loved it, the next I felt deep derision. I laughed out loud. I scoffed aloud. It was a roller coaster. A good roller coaster? I just don’t know!

She’s the Man is a 2006 movie (Amanda Bynes, Channing Tatum) based on Twelfth Night. Like Twelfth Knight, it has similar names and the overarching story, but none of the details and no one-to-ones. It takes place in a modern high school (two high schools, one a boarding school, actually), where a girl who can’t play soccer because her school only has a boys team poses as her brother to go to another high school and play soccer… against the a-holes who wouldn’t let her play in the first place. And there’s the relationship-dimension to it, of course, cuz her roommate and fellow soccer player has no idea she’s a, well, she, and yet strange sparks are a-flyin’.

It is a divisive movie. It won both a Kids Choice Award and a Stinker. Was it meant to be terrible because it was based on Shakespearean farce? I dunno. But the acting was probably the worst bit of it (despite what you might read elsewhere). And I guess the absurdity, but that is understandable. Laughable at times, and not necessarily because it’s funny. Has it held up with all the recent changes in the social discourse on gender and gender identity? Almost? Yes? Basically. Definitely worth watching, but you’ll likely either thank me heartily or threaten me for having recommended it. About a fifty-fifty shot, I’d say.

TWELFTH NIGHT

“If music be the food of love, play on, / Give me excess of it” (A1, s1)

“I am sure / care’s an enemy to life” (A1, s3).

“Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage” (A1, s5).

TWELFTH KNIGHT

“The thing is that a) we are nerds, by which I mean we collectively make up the top 1 percent of our graduating class and are probably going to rule the world someday even if it loses us some popularity contests…” (p6).

“Because apparently I’m supposed to be nicer if I want people to agree with me. (Big ups to my grandma for that sage advice)” (p8).

“Because when boys hear a girl’s voice, they either come for unnecessarily, thinking you’ll be easy prey, or the think everything you say is flirting. Being nice to a geek while being visibly female is the kiss of death. Do you know how many times I’ve gotten vulgar messages or explicit pictures? And if I say no, do you know how many times I’ve been called a bitch?” (p33).

“So of course I’m angry. I’m angry all the time. From the betrayals of my government to the hypocrisies of my peers, it seems like the awfulness never rests and neither can I” (p34).

“And it’s not just me–I don’t know how any girl can exist in the world without being perpetually furious” (p34).

“‘I’m fine.’ By which I mean a few things: I’m angry as shit, and bitter, too. I don’t know what the hell kind of future I have now’ …. But what comes out of mouth is ‘Dunno. I’m bored.’ / ‘Ah,’ says Nick with a nod, clearly relieved I haven’t offered up something way darker, so I know I said the right thing'” (p49).

“I push my chair back, feeling that weird amalgam of things that only happens when you’ve stayed up way too late and the whole world feels kind of fake, like maybe nothing else exists outside of you and your thoughts” (p100).

“I already know there’s something wrong with me; I know there’s a reason people don’t like me. Lots of reasons. / But secretly, I would like someone to see me for what I am and choose my anyway” (p100).

“He’s unbearable. ‘You do know that telling girls to “chill” is a famously bad call, right?’ / ‘Don’t’ sell yourself short, Vi,’ he says in one of his falsely cheerful voices. ‘You’re not just any girl. You’re a fun little tyrant'” (p103).

“It’s not about being better, or being stronger, or being right. Certainly not of the cost is your change to feel love and acceptance” (p106).

“Because the only thing in this life that actually matters is how we’re connected to each other” (p106).

“‘But I think I’d be embarrassed to do something wrong. Or say something dumb.’ / ‘Why? Boys never worry about all the dumb things they say and do, trust me,’ I mutter, and she laughs” (p113).

“Everyone wants racism to be this bomb they can disarm rather than what it is, which is… fluid” (p125).

“For some reason–cough, imperialism–a person is free to dream up a world with mythical creatures and magical powers so long as it’s still mostly British” (p133).

“My swagger is built on a foundation of adoration and envy. Hers is flat-out refusal ro let anyone tell her who to be” (p144).

“‘What if I don’t see any other paths?’ / I sigh. ‘It’s just a metaphor, Orsino. We’re teenagers. We don’t know what comes next” (p162).

“…Vi, wanting someone in your life doesn’t have to mean you’re weak. It doesn’t mean you’re soft. It just means there’s someone in this world who makes you like everything just a little bit more when they’re with you, and in the end, isn’t that something?” (p207).

“Darling Viola, my clever, brilliant girl. The last thing you need is more thinking” (p208).

“Sometimes it feels like there’s a cliff-edge, the right moment for the truth, and you either pull yourself back from it or you sail headfirst into a crevasse” (p209).

“‘Why are feelings so brutal?’ she wails. ‘Everyone makes friendship seem like garden parties and sleepovers when really it’s Jurassic Park for emotions” (p211).

“It was a relief to finally understand, then a smack upside the head to realize I wasn’t remotely the center of her narrative…” (p213).

“It was a simpler time when I could look around at all the incompetence and decide for myself how things should be done” (p220).

“…but in the end, it doesn’t matter what you could have done. It matters what you do, and more importantly, it matters who you do it with” (p257).

“It matters how we choose to take the field. It matters what we see when we look at our possibilities” (p257).

“You act like you’re all alone, but you’re not. You’ve never been alone. You just didn’t want to choose what I had to give you” (p266).

“You told me that if I decided to be myself, I wouldn’t have to be alone,’ she says simply. ‘Neither will you'” (p272).

“‘You’re not a bad person. You’re just a weirdly difficult one.’ / ‘Okay–‘ / ‘And you’re scared, Vi. You’re so scared of everything'” (p286).

“But I also told her that being angry didn’t mean I didn’t care about her, or that I would rather let that anger undo the things between us that I knew were real” (p294).

“It’s the thing that happens to you while you’re wide awake and dreaming” (p301).

“The game isn’t the dice. It’s who’s with you at the table” (p301).

August 31, 2024

What to Read in September

I considered a back-to-school theme for September’s what to read theme, but that stopped appealing when I thought how much no one wants to be handed more work to do at the beginning of the school year. Maybe I’ll do that next year. Instead, I’m going with a writing theme. Why? Because I am already gearing up for Nanowrimo. Backing it up, October will be novel planning month (either Nanoplamo or, as I’m calling it this year, Octnoplamo). Because of some project deadlines, that makes September editing month for me (just this year, but we’ll see). I am calling it Sepnoedmo and I am aware the acronym doesn’t quite work. It sounds right. And I am neck-deep in writing books so maybe you should be too.

These are some of my favorite books on the writing process and craft, for editing, planning, writing, and even getting your work out there. There are so many great books (and classics) I haven’t read yet.

On Writing

, Stephen King

Bird by Bird

, Anne Lamott

Zen in the Art of Writing

, Ray Bradbury

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

, Jessica BrodyOutlining Your Novel, K. M. WeilandThe Business of Being a Writer, Jane Friedman

On Writing

, Stephen King

Bird by Bird

, Anne Lamott

Zen in the Art of Writing

, Ray Bradbury

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

, Jessica BrodyOutlining Your Novel, K. M. WeilandThe Business of Being a Writer, Jane Friedman

This list is low on craft books because I am finishing up the editing phase of my top-priority project and looking forward to trying to find an agent… and selling it. So it’s a lot of that. I have tabled Wonderbook (Jeff VanderMeer) and left A Swim in the Pond in the Rain (George Saunders) on the shelf. Just for this season; I’ll return to them. This list is more for taking what you’ve already written and getting it ready for submission and then navigating after that. Many of them were recommended in the appendix of The Business of Being a Writer.

The First Five Pages, Noah LukemanThe Writers’ Guide to Queries, Pitches and Proposals, Moira Anderson AllenSave the Cat! Writes a YA Novel, Jessica BrodyHow to Write a Mystery, Mystery Writers of America, Lee ChildOpen Page, Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative WritingRefuse to Be Done, Matt BellGet Signed, Lucinda HalpernBefore and After the Book Deal, Courtney MaumFormatting and Submitting Your Manuscript and Get a Literary Agent, Chuck SambuchinoThe Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published, Arielle EckstutThe Forest for the Trees, Betsy LernerThe Portable MFA in Creative Writing, NY Writers’ WorkshopThe Modern Library’s Writer’s Workshop

The First Five Pages, Noah LukemanThe Writers’ Guide to Queries, Pitches and Proposals, Moira Anderson AllenSave the Cat! Writes a YA Novel, Jessica BrodyHow to Write a Mystery, Mystery Writers of America, Lee ChildOpen Page, Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative WritingRefuse to Be Done, Matt BellGet Signed, Lucinda HalpernBefore and After the Book Deal, Courtney MaumFormatting and Submitting Your Manuscript and Get a Literary Agent, Chuck SambuchinoThe Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published, Arielle EckstutThe Forest for the Trees, Betsy LernerThe Portable MFA in Creative Writing, NY Writers’ WorkshopThe Modern Library’s Writer’s WorkshopThese are the titles that “everybody” is looking forward to being published in September:

The Life Impossible, Matt HaigHere One Moment, Liane MoriartyThe Hitchcock Hotel, Stephanie WrobelThe Booklover’s Library, Madeline MartinWe’re Alone, Edwidge Danticat (short story collection)Quarterlife, Devika RegeAdam and Evie’s Matchmaking Tour, Nora NguyenCreation Lake, Rachel KushnerFinal Cut, Charles Burns (YA graphic novel)The Gates of Gaza, Amir Tibon (memoir)The Empusium, Olga Tokarczuk (Nobel prize translation)Intermezzo, Sally RooneyThe Women Behind the Door, Roddy DoyleColored Television, Danzy SennaLovely One, Ketanji Brown Jackson (memoir)Somewhere Beyond the Sea (The House in the Cerulean Sea sequel), T. J. KluneNexus, Yuval Noah HarariEntitlement, Rumaan AlamPlayground, Richard Powers

The Life Impossible, Matt HaigHere One Moment, Liane MoriartyThe Hitchcock Hotel, Stephanie WrobelThe Booklover’s Library, Madeline MartinWe’re Alone, Edwidge Danticat (short story collection)Quarterlife, Devika RegeAdam and Evie’s Matchmaking Tour, Nora NguyenCreation Lake, Rachel KushnerFinal Cut, Charles Burns (YA graphic novel)The Gates of Gaza, Amir Tibon (memoir)The Empusium, Olga Tokarczuk (Nobel prize translation)Intermezzo, Sally RooneyThe Women Behind the Door, Roddy DoyleColored Television, Danzy SennaLovely One, Ketanji Brown Jackson (memoir)Somewhere Beyond the Sea (The House in the Cerulean Sea sequel), T. J. KluneNexus, Yuval Noah HarariEntitlement, Rumaan AlamPlayground, Richard Powers

These are the book I will be reading for book clubs this month:

The Chocolate War, R. CormierA Magic Steeped in Poison, Judy I. LinNorth Woods, Daniel MasonThe Sun and the Void, Gabriela Romero LaCruzThe Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley

The Chocolate War, R. CormierA Magic Steeped in Poison, Judy I. LinNorth Woods, Daniel MasonThe Sun and the Void, Gabriela Romero LaCruzThe Ministry of Time, Kaliane BradleyThese are the books I will be attempting to squeeze in because of book events I am attending:

Digger Volume 1, Ursula VernonA Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking, T. KingfisherThe Dutch House, Ann PatchettBel Canto, Ann PatchettTom Lake, Ann Patchett

Digger Volume 1, Ursula VernonA Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking, T. KingfisherThe Dutch House, Ann PatchettBel Canto, Ann PatchettTom Lake, Ann Patchett

Cat’s Cradle, Kurt VonnegutThe Marriage Portrait, Maggie O’FarrellTwelfth Night, William ShakespeareTwelfth Knight, Alexene Farol FollmuthMartyr!, Kaveh Akbar

Cat’s Cradle, Kurt VonnegutThe Marriage Portrait, Maggie O’FarrellTwelfth Night, William ShakespeareTwelfth Knight, Alexene Farol FollmuthMartyr!, Kaveh Akbar

Never mind. I’m going to include some back-to-school recommendations in the spirit of the season. Also because I am working on an edit of a Ninth Grade Language Arts curriculum I taught a few years back. (Someone else is using this curriculum this year.) These are my top recommendations for ninth grade English, then. Note: they are a little on the masculine side because I had all boys in my class. Also, I consider ninth graders to still be in the same developmental stage as seventh and eighth graders—plus I had some real reluctant readers—so these novels tend to be shorter and easier than what you might normally see in high school reading. If you want a stretch, head down to The Lord of the Rings or the Shakespeare.

The Invisible Man

, H. G. Wells

The Hound of the Baskervilles

, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

A Christmas Carol

, Charles Dickens

March

, John Lewis

American Born Chinese

, Gene Luen YangMacbeth, William Shakespeare (Folger’s)

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

, Douglas AdamsThe Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, Paul ZindelThe Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway

Anne of Green Gables

, L. M. Montgomery

Bridge to Terabithia

, Katherine Paterson

Where the Red Fern Grows

, Wilson Rawls

When You Reach Me

, Rebecca Stead

The Giver

, Lois Lowry

The Princess Bride

, William Goldman

The Book Thief

, Marcus ZusakThe Maze Runner, James DashnerA Monster Calls, Patrick NessThe Graveyard Book, Neil Gaiman

The Truth About Horses,

Christy CashmanTreasure Island, Robert Louis StevensonLord of the Flies, William GoldingCall of the Wild, Jack LondonCaptains Courageous, Rudyard KiplingRed Badge of Courage, Stephen CraneAdventures of Tom Sawyer, Mark TwainAdventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

Old Yeller

, Fred Gipson

The Great Gatsby

, F. Scott FitzgeraldTo Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

The Hunger Games

, Suzanne CollinsBorn a Crime, Trevor Noah

The Hobbit

, J. R. R. TolkienThe Lord of the Rings trilogy, J. R. R. Tolkien

The Screwtape Letters

, C. S. Lewis

The Invisible Man

, H. G. Wells

The Hound of the Baskervilles

, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

A Christmas Carol

, Charles Dickens

March

, John Lewis

American Born Chinese

, Gene Luen YangMacbeth, William Shakespeare (Folger’s)

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

, Douglas AdamsThe Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, Paul ZindelThe Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway

Anne of Green Gables

, L. M. Montgomery

Bridge to Terabithia

, Katherine Paterson

Where the Red Fern Grows

, Wilson Rawls

When You Reach Me

, Rebecca Stead

The Giver

, Lois Lowry

The Princess Bride

, William Goldman

The Book Thief

, Marcus ZusakThe Maze Runner, James DashnerA Monster Calls, Patrick NessThe Graveyard Book, Neil Gaiman

The Truth About Horses,

Christy CashmanTreasure Island, Robert Louis StevensonLord of the Flies, William GoldingCall of the Wild, Jack LondonCaptains Courageous, Rudyard KiplingRed Badge of Courage, Stephen CraneAdventures of Tom Sawyer, Mark TwainAdventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

Old Yeller

, Fred Gipson

The Great Gatsby

, F. Scott FitzgeraldTo Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

The Hunger Games

, Suzanne CollinsBorn a Crime, Trevor Noah

The Hobbit

, J. R. R. TolkienThe Lord of the Rings trilogy, J. R. R. Tolkien

The Screwtape Letters

, C. S. Lewis

August 30, 2024

Writer in the Wild: Sepnoedmo

I’ll bet a bunch of you kinda know where this is going with the title that I gave this blog. I see you.

The thing is, I have a conference coming up at the end of October. I also have the opportunity to hit up some beta readers in October. And the conference has pitches built into it. Therefore, I really need to have my novel revised by October 1.

Nanowrimo (National Novel Writing Month) is coming up on November 1. October is traditionally the month to plan a novel anyway (which I am now calling OctNoPlaMo). This year and maybe this year only, then, September will be SepNoEdMo.

I am aware that the acronym is wrong. (Is it an acronym when it takes chunks of letters instead of just the first letter? Is there another name for that?) Technically the word “November” is nowhere to be found in “NaNoWriMo,” but—correct me if I’m wrong—it’s always felt like it was in there, what with all the N’s and the “No.” And just changing the “Wri” to “Ed” and “Pla” (Nanoedmo and Nanoplamo) would be boring. So here it is, my slightly nonsensically named Sepnoedmo: September Novel Editing Month. Or maybe even September’s Novel Editing Month. It is.

At any rate, I am gearing up this week finishing another project (that I promised someone) so that on September 1 (two days!, this Sunday!) I will be at the laptop digging way down deep into editing the novel that I am going to pitch at the conference. Which by the way is the novel that I wrote 50,000 words on two Nanos ago and finished this past March. (Last year for Nano I was distracted by another book that I had been working on at a residency in October and that’s the one I’m going to work on this Nanowrimo again. I think. I mean, if I sell the first book in a trilogy then they’ll probably make me work on the second one. Fingers crossed that I have a they sometime soon.)

I can’t give it a number, however. In other words, there won’t be a goal, exactly, which is what makes Nanowrimo what it is. I have tried to enter number goals before for editing, but it doesn’t always work out. Sure, you can say that each page edited equals X words and then do that, but if you are not doing a direct read-through edit or a proof-reading kind of thing, then there are no pages to count to begin with. I am using Fictionary for my story-level edit, so I won’t be moving page by page, I’ll be jumping around.

Actually, I just thought of something. I could give time an arbitrary page number. Figure out the number of hours I could put in daily that would stretch me like Nanowrimo would, almost to the point of impossibility, and give it a number. You know, Nanowrimo lets you make goals at any time of the year, now? I could run my own Sepnoedmo on Nonowrimo’s site. That’s what I’ll do. It’ll be great. I just need to do some math. The max amount of hours I could imagine putting in each day and then divide 1,667 by that. Then each hour equals that many words, every quarter hour a quarter of that, and I won’t break it down any smaller. For every fifteen minutes I’m editing I will tell Nano’s site that I wrote whatever that word-number is. Cool.

We’ll talk Octnoplamo in about a month.

Feel free to join me. I have to go; I have work to do.

August 23, 2024

Book Review: The Marriage Portrait

I keep coming back in my mind to reading Hamnet in February. I hadn’t read Maggie O’Farrell before, and I was just waiting to come back to her. The Marriage Portrait—her newest book, from 2022—was my chance. While it did not disappoint, I ended up liking Hamnet better, but only because of a few things, one main thing. Overall, the writing is breathlessly beautiful, the story poignant and taut. But it is wordy. And the ending… I loved the book, but was let down by that ending even though I found what happened satisfying, just not how.

Lucrezia is the third daughter of the Duke of Firenze. It is the 1550s and her sister dies before she can be married off to the soon-to-inherit Duke of Ferrara. So before she realizes what could be happening, the too-young Lucrezia is promised to the soon-to-be Duke. She clings to her familiar home where she has been cloistered for her whole life, lost in her painting and her wild imagination. But before she’s even sixteen, she’s married to man she doesn’t know and carried off to her new home across mountains and away from everything she’s ever known. And no one ever tells her what is going on. It’ll take months before the truth sets in: she must produce an heir for the Duke. And fast. Or else.

The Marriage Portrait is historical fiction based very loosely on the life of Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici d’Este, who was married to the Duke of Ferrara. There are a few surviving paintings of her and it is thought Robert Browning’s “My First Duchess” was about her. Because she was the first Duchess of Ferrara and she died not long after marrying the Duke. There were rumors of foul play.

It is true that I usually have a lot more to say about a book I didn’t like or that I can’t decide if I like than I book I enjoyed or even loved. I don’t know how much I am going to have to say about The Marriage Portrait, but it is doubtful it will be near as much as I said about poor Radiance. I just couldn’t stop complaining.

It is official; O’Farrell can write. Man, can she write! Her prose is so lush, so beautiful. (See quotes below.) She is so creative in the way she says a thing, everything. I get lost in her writing, in her style, in her imagination, in her description.

I have the same complaint as with Hamnet, about the tenses changing all over the place. And there were just way too many words in this one, like O’Farrell wasn’t edited nearly tightly enough. But my big issue was with the main character and the ending—it was all coincidences and no spirit, no fight. I could see every detail about it ahead of time, but it would have been much more powerful (even if I saw it coming) if there was some agency, if Lucrezia had had ANYTHING to do with the outcome. (I was recently accused of letting a side character have the final moment of victory in a book—that person would be horrified if they read The Marriage Portrait.)

I understand—part of the point of this book is that women, especially this daughter of a powerful man in 1550s, would have no agency, no recourse or alternative to anything especially if the husband who essentially owns her is some sort of psychopath or maybe has a personality disorder. (Does he? That’s part of the mystery. Who is this guy? What’s not a mystery is that Lucre in kept ignorant and innocent of so many things and then valued only for her fertility, will be discarded if she doesn’t have that in spades). However, for the sake of story, she should not have been allowed to stay in this truly uncomfortable, painful reality. Just for the sake of story. We already get the point, we can feel her naivety and powerlessness in our bones.

Though there is enough of a twist. Even if it’s a twist made up of coincidences. I was kept on my toes, on a high wire, throughout much of the story, and on some level I was happier with the ending than I thought I was going to be.

Not to make this sound like some sort of thriller. The only way we get tension is through the back-and-forth narration, between the chronological story of Lucrezia’s life to her moments in an isolated fortress where she realizes her husband is trying to kill her. (Or is he?) There are many, many scenes that build layers of beautiful imagery and lush setting and even reinforce character way more than they move the plot forward. Lots and lots of palazzo scenes and always claustrophobically close to Lucrezia. Which is part of how we feel her in-the-darkness and helplessness. Still, too many of these scenes, too many words.

But what lovely words! I did enjoy it. I would recommend it. I would propose it is a study in how not to let your ending happen to your heroine. There were many moments that Lucre could have done something—even a small thing—to at least help with her ending. Then it would have been almost perfect. I’ll still be waiting to read the next O’Farrell (which for me will be I Am, I Am, I Am; she has not announced any new project but has a backlist I can get work my way through).

“It would return to her, she knew, this story, in the dead of night. Iphigenia, with her slit throat, like a vibrant scarf, would shuffle up to the bed where Lucrezia lay, and she would paw at the blankets, wanting to touch Lucrezia with her cold, bloodied fingers” (p28).

“She has reached a place where all she craves is an end to the torment, the bodily suffering. Any end at all” (p93).

“She lifts her chin, seizes the candle from Emilia and thrusts it out at arm’s length. She is not afraid, no, she is not. A beast—muscled and brave—lives within her. She tells herself this over the cantering of her heart. Let the ghouls that hover in the corners of the room see what they are dealing with: she is the fifth child of the ruler of Tuscany; she has touched the fur of a tigress; she has scaled a mountain range to be here. Take that, darkness” (p128).

There is supposed to be movies for both Hamnet and The Marriage Portrait in the works. They each have directors and some other things.

Book Review: Cat’s Cradle

After an adulthood avoiding Kurt Vonnegut, I finally read Cat’s Cradle. I immediately wondered what had been wrong with me to avoid Vonnegut. Cat’s Cradle is written in clear, straightforward prose with short, snappy sentences and paragraphs. It’s a little strange and the science fiction part of it is just a little science-y and a bit more satire. Vonnegut has a dry sense of humor (which we’ll talk more about in a minute) that not so much shines as glares light on humanity while dealing with the big questions of his day and all the days. It is very Cold War, but it’s also full of things and people and issues we recognize today. And then, dear reader, you have fun reading it.

Synopsis: Felix Hoenikker is one of the eccentric geniuses behind the atom bomb. He also invented a little thing called “ice-nine” before he died, and John, an aimless reporter, is interested in this fact. He follows the trail of ice-nine after Hoenikker’s three, bizarre children, out to a tropical island and into the heart of a despotic regime and an illegal religion. If ice-nine is there—if ice-nine is anywhere—it could mean the end of the world.

I said I would talk again about his wry sense of humor. Here’s the thing, I did read this book for a book club. But I also read it because when I was I had a manuscript session at a writing residency this past spring, the author giving me feedback told me my humor was similar to Vonnegut’s, as were maybe some other things (I tend to be a keen observer who writes with my tongue in my cheek), and I should read his works. So I was at first surprised, but then happy to start here.

I did not find this book nihilist or even particularly pessimistic. Just satirical. Existentialist. But existential despair? More existential absurdist. Which hopefully shows you that I did not nail the description of the book above. Those are the bare bones of the story, but the voice of Vonnegut is what carries anything about it.

And Vonnegut was a Humanist. (“Famously” a Humanist, as one person in my book club kept saying.) According to Google, Humanism is “an outlook or system of thought attaching prime importance to humans rather than divine or supernatural matters” …. “stress the potential value and goodness of human beings, emphasize common human needs, and seek solely rational ways of solving human problems.” Yeah, that totally checks out. These ideas are all over this book, right there with the Cold War question of “Are they going to push the button?” You could also call it irreverence. Or sacrilege. It’s kinda all three.

The moral I got from it was also that one bad apple… you know. And that bad apple’s existence is inevitable. I mean, eventually one of the many bad apples is going to get some real power… Also, who has power? And what accidents have we already set in motion? It’s a war-minded, sci fi, postmodern story on the verge of being postapocalyptic, inspired by the beat poets. I thought it was going to be bizarro, but it ended up feeling homey, fun, and magical to me. Even if it was kinda sad in its commentary and events. Like a sad circus, a bit.

John, the narrator… well, we only hear his name on the first page. He is totally in this story and there are even moments when his actions matter, but for the most part he is a non-entity narrator. He is a mirror. He is made of glass. He is see-through, like a ghost. He is more of an observer, and a bland observer at that, especially compared to all the other characters. But this felt intentional, right.

PS. According to a physicist (or two) in my book club, there is a real ice-nine. But this is a fictionalized version of ice-nine, much more stable and dramatic. The physicist muttered, “It would have made more sense to say it was ice-thirteen, actually…”

PS2. There is a Moby Dick reference at the very beginning.

As a co-reader said at club, “The book ends when he finds his purpose—not when he carries it out.” Which is another way of saying that some people will wish Vonnegut had written more at the end. I was good with it. Though I do agree the ending felt fast. Then again, the whole thing felt fast. It’s not a long read. It’s a classic. I enjoyed it. I can’t believe a lot of Vonnegut’s work is out of print.

Some recommended reads to go along with this one would be White Noise by Don Delillo and Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon.

Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) was a prolific, popular, and lauded writer of wry, satirical, humanist-fatalist speculative fiction short stories and novels. He was from Indianapolis, where he grew up affluent in a successful family until Prohibition and The Depression plunged them into poverty and struggle. He went to Cornell and majored in biochem before poor grades led him to enlist in the draft. After his mother committed suicide (struggling with alcohol and prescription drugs), he left for WWII, where he was taken prisoner by the Germans.

When he returned, he went to University of Chicago for a graduate degree in anthropology, was married to his high school sweetheart, and became a journalist. He couldn’t handle working in PR in upstate New York, so he became a writer of fiction in Cape Cod (despite mostly rejection) and had six kids. His first short stories were science fiction, as were his first novels, a few years later.

He didn’t like the label “science fiction,” but wrote about technology and humanity, at least at first. He developed his wry, satirical style as well as his fictional alter ego, Kilgore Trout. His popularity grew with Player Piano and Sirens of Titan, Breakfast of Champions and Slaughterhouse-Five (about his experience in the war and his breakthrough novel, named after him surviving the bombing of Dresden in a meat locker of the slaughterhouse where he was held).

His wife converted to Christianity and their marriage couldn’t survive the strain of their differing worldviews, though they remained friends. He married again later and adopted a seventh child. He suffered from depression and attempted suicide in 1984. He also published other novels, plays, collections of short stories, and collections of essays, even political nonfiction. There is a Memorial Library in Indianapolis devoted to him and his work.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, I stand before you now because I never stopped dawdling like an eight-year-old on a spring morning on his way to school. Anything can make me stop and look and wonder, and sometimes learn. I am a very happy man. Thank you” (p11).

“Why would I bother with made-up games when there are so many real ones going on?” (p11).

“Dr. Hoeknikker used to say that any scientist who couldn’t explain to an eight-year-old what he was doing was a charlatan” (p34).

“New knowledge is the most valuable commodity on earth. The more truth we have to work with, the richer we become” (p41).

“Bokonon says” ‘Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God’” (p63).

“’Life is sure funny sometimes.’ / ‘And sometimes it isn’t.’ said Marvin Breed” (p66).

“They were lovebirds. They entertained each other endlessly with little gifts: sights worth seeing out the plane window, amusing or instructive bits from things they read, random recollections of times gone by” (p86).

“’Americans,’ he said, quoting his wife’s letter to the Times, ‘”are forever searching for love in forms it never takes, in places it can never be. It must have something to do with the vanished frontier”’” (p97).

“…Americans, in being hated, were simply paying the normal penalty for being people, and that they were foolish to think they should somehow be exempted from the penalty” (p98).

“She broke my heart. I didn’t like that much. But that was the price. In this world, you get what you pay for” (p128).

“If you want an expert opinion, money doesn’t necessarily make people happy” (p152).

“So I said goodbye to government, / And I gave my reason: / That a really good religion / Is a form of treason” (p173).

“’Maturity, the way I understand it,’ he told me, ‘is knowing what your limitations are’” (p198).

“’It is not possible to make a mistake,’ she assured me. / I did not know this was a customary greeting given by all Bokononists when meeting a shy person” (p203-204).

“Do writers have a right to strike? That would be like the police or the firemen walking out …. When a man becomes a writer, I think he takes on a sacred obligation to produce beauty and enlightenment and comfort at top speed” (p231).

“’Sometimes the POOL-PAH,’ Bokonon tells us, ‘exceeds the power of humans to comment.’ Bokonon translates pool-pah at one point in The Books of Bokonon as ‘shit storm’ and at another point as ‘wrath of God’” (p244).

“Perhaps, when we remember wars, we should take off our clothes and paint ourselves blue and go on all fours all day long and grunt like pigs. That would surely be more appropriate than noble oratory and shows of flags and well-oiled guns” (p254).

“’What do they mean, anyway?’ echoed Ambassador Horlick Minton. They mean, ‘For one’s country.’ And he threw away another line. ‘Any country at all,’ he murmured” (p256).

“Beware of the man who works hard to learn something, learns it, and finds himself no wiser than before” (p281).

“Newt made a shrewd observation. ‘I guess all the excitement in bed had more to do with excitement about keeping the human race going than anybody every imagined” (p283).

“’I know now what my karass has been up to, Newt. It’s been working night and day for maybe half a million years to get me up that mountain.’ I wagged my head and nearly wept. ‘But what, for the love of God, is supposed to be in my hands?’” (p286).

There are very few adaptations of Vonnegut’s stories out there, which is super-surprising to me. At any rate, there’s nothing for Cat’s Cradle. How White Noise got made and not Cat’s Cradle is beyond me.

Book Review: Radiance

I have never felt such strong emotion in both of two opposite directions as I did while reading Radiance by Catherynne M. Valente. I am not alone in either hating or strongly admiring this book, and I even found another reader who felt exactly as I did: I hated the book for a good long while, then I got really angry because I found some bits to be brilliant (in the other reader’s words, “Wait? Do I like this book?”), I flip-flopped there for the third quarter of the book (a little longer than that) and then I went frantic at the end wanting Valente to stop talking before she ruined the book again. (Too late.) At book club there were some very strong opinions and was also so much to talk about. But maybe that’s because there was just too much crammed into the darned thing.

Severin Unck—darling of the nine planets’ silent picture screen since she was a baby—has disappeared. According to the one witness who was there, she was there one second and gone the next. Or was there only one witness? And was she there one second and gone the next? All we know is that she was on Venus shooting a documentary that meant a lot to her, with her true love and several other people who had been around for awhile in the glitzy, debauched world of Oxblood Pictures. But there were others at home too, on far-flung planets, who have a stake in her life and who want to know: where is she? And is she alive? And can they keep their secrets while still asking these two, crucial questions?

Well. This was just another book club read, for the speculative fiction book club I am in. It was time for a sci-fi read and the group leader held this one up. Didn’t really look like much till you looked closer: the telescope which the woman gazed at the stars through was an old-timey camera. Hmm. Then the cover copy says, “Radiance is a decopunk pulp SF alt-history space opera mystery set in a Hollywood-and solar system-very different from our own.” Hm, hm, hmm. Promising, right? But what I was not told in the packaging of this book could fill, well, a book. Important thing to know number one: Radiance is less a deco-punk alt-history (though it has a little alt history mostly overshadowed by the fantastical) and more of a trippy, sometimes phantasmagorical mash-up of space opera, sure, but then horror, gothic, noir, mystery, old Hollywood, art deco, Victorian, fairy tale, Who Framed Roger Rabbit with The Truman Show THING with endless references to Greek mythology (especially the Lotus Eaters and the Grey Sisters), The Wizard of Oz, Edgar Allan Poe, Dracula, and I think a bunch of early twentieth-century (Ray Bradbury-ish) sci fi that I didn’t catch, all written IN A LITERARY FICTION writing style. Important thing to know number two: it is nonlinear, non-reliable, non-obvious, pieced together and presented as letters, journal entries, movie scripts, interviews, PSAs, ship manifests, whatever. Which means it will take some serious time to figure out what you are even reading. Important thing to know number three: it is FLUID-FILLED, by which I mean milk and blood are flying everywhere, as well as some insinuated other bodily fluids because there is a whole lotta f*ing (which is the word that is used every single time). So that’s the real lead-in to this book. Do you want to read it, now? You may.

I began this book thinking it was going to be just another sci-fi book. I studied the chronology and the list of settings symbols (the planets and Earth’s moon) at the beginning, three quotes, then jumped right into a scene where a docent or some-such is ushering people into the “prologue,” which is also film projected on their naked bodies? Okay. We’re already so meta. A few pages later and I am in a completely different place, where one editor-in-chief and then another go back and forth between two movie premier red carpets’ gossip across almost thirty years, which you won’t understand unless you kinda study the short chapter first, looking at the end as well as the beginning. Okay. Then after two more quotes we enter Part One of the book. And a short scene of a movie that ends in damaged film. Then two pages of video footage from a personal reel. Then audio from a production meeting, and by the last one we’re in the future of the story? Turn the page and I am on p. 46.

I am a great reader. I am a terrible listener. (I have trained and learned, so I’m not as bad as I once was. However, I still have ADHD.) I don’t listen to audiobooks (while reading the first time) because I have a hard time paying attention that way and absorbing what’s going on. And I don’t enjoy it nearly as much as putting my eyes on a page. However, by the time I was a tenth of the way into this book I had set it down no fewer than ten times and had let several days pass while I read in tiny pieces. I had picked up other books randomly, starting first chapters of other books just to (subconsciously) avoid returning to Radiance. Where was I? What was going on? And more importantly, couldn’t we stay in one scene long enough to let me enjoy actually reading??? I decided I hated this book. I got very passionate, waving my arms about holding a chef’s knife and a stalk of celery telling my husband that no matter how literary and experimental you wanted to be, it was the job—THE JOB—of a writer to usher the reader into their book, to orient them, welcome them (no matter how hostile-y) and provide some sort of hook (and don’t you dare tell me that’s a dirty word because it is not! And it is also not slummy!) Valente had failed me. So I bought the book on audio. (Sigh.)

I had used this method one other time in my life, and that was last fall when I was bound and determined to read Dracula and was a quarter of the way in and basically bored out of my mind. The audio turned on every time I got in my car and eventually I had listened to the whole darn thing. It was not painless. I figured Radiance could turn on every time I got in the car and with carpool and whatnot I would be through with the book before book club. I finished the book an hour before club, laying in front of my dog’s kennel petting his soft little head with one hand, my other hand grasping my smartphone as poor Heath Miller did virtual, frenetic cartwheels with his voice, gasping to a grand finale full of goofy cartoon voices and multiple accents—including a character who suddenly speaks in a Cornish accent for half a page. (Note: I ended up reading a few more sections on the page over the course of the book.)

Which means I didn’t study this book the way it is really meant to be studied as it is read. But somehow Miller (the audiobook narrator) managed to keep me basically aware of when in time, where in the universe, and in what tone I was reading—along which storyline. (I can’t believe I am only at this point in my review. This is going to be stoopid long.) For a long time, as I listened to the book, I kept hating the book. Then there was this one day, this one hour, this one moment when Valente dropped something (she has so many mic drops and secret reveals and cool references and beautiful phrases!) and I was actually soaring with the moment, with the prose, and I resisted that sucker. No way was I going to start enjoying this book now. But then there were more moments. And more things. And then we went back to the stuff I had grown to hate (and I think rightly): Valente’s pretentious, confusing, and masturbatory writing style. (Sorry. There is no better word for it than that.)

I mean, I read a few of her quotes from her interviews, and it sounds to me like she was all “I want to write this and I want to write this and this and this and this,” and instead of writing a bunch of books she just slammed all those ideas into one blob and spent seven years shoe-horning every last moment and idea into 500 pages. While on one hand she clearly had a crazy-deep familiarity with her material (and the research that went into it)—so much so that she forgot to initiate us into plenty of it—on the other hand she didn’t cut nearly enough. Sure, she could have broken it down, got rid of some of the wacky ideas, but that’s not actually what I ended up wanting in the end. In the end, I just wished she had cut some stinking adjectives, some repetitive phrases, some words! This is not poetry. This is not us watching Valente play with words. Oh wait, it is. But it shouldn’t be. Pick an image, a phrase, a metaphor, and whip the unused one out the window. This book is a study in too much. Cut your frickin’ darlings, darlin’.

And somehow, with so many characters and settings and storylines, the words and the experimental structure prevents the characters from becoming real, prevents the settings from being fully drawn or seeable, prevents the reader from being invested in the story(s). This is a meta novel, I guess, that doesn’t quite work on the level of a normal novel. It’s an idea book. It’s an experiment in Valente’s interests.

I’m gonna list out the rest because I’m sure you’re losing steam for reading this.