Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 12

May 14, 2024

Book Review: Small Great Things

Thank goodness I have finally returned to reading decent books. That’s not great books. But it’s an improvement over bad books. Which means, yes, I thought that Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult was a decent book. Not a great book. And thankfully not a bad book. It’s definitely a book club kind of book, and many book clubs have really enjoyed it. Ours was split and I found myself on both sides. It was definitely easy to read, even if it did go on too long. Then again, the easy writing style only worked once I got past the idea that I would have to read in the POV of a white supremacist. That was a thing that almost saw me put the book down.

We have here a story told from three perspectives. First, we have Ruth, a Black, single mother and labor and delivery nurse who is targeted in a murder case by racist parents when a baby under her care dies. Then we have Turk, a hard-core white supremacist who has married the love of his life who happens to be white-supremacist royalty. He heads to the hospital with his pregnant wife and dreams of their healthy baby purifying their race, but goes home emptyhanded and furious. And then there’s Kennedy, a young, white mother and the appointed public defender who is inexperienced and perhaps naive but now in charge of Ruth’s case… and all of their futures.

Many people have read Jodi Picoult before. This was my first experience. But I am led to believe that her books are crafted in such a way that they just scream “Recommend me for your book club!” Maybe on purpose; maybe it’s just her style. While I would think this was a fine thing—finding your audience and writing in that niche—some of the people at group were more accusing Picoult of something, insinuating that she picked hot topics and manipulated her readers with them. Well, as much as it seems correct that she likes to write about issues, I also don’t see book clubs actually discussing the real issues she writes about—just the books. But then the reader has read about the issues, at least. Perhaps with emotional rails that lead the reader in a certain direction. I guess I’m saying plenty of readers don’t mind being manipulated, if you want to use that word for it.

For me, though, when you have the lawyer (character) concluding, “She [the accused] doesn’t need my advice, because really, who am I to give it, when I haven’t lived her life?” (p415), I think we’ve lost our way with the moral and the story, some. She’s her lawyer, a lawyer the defendant consistently refuses to listen to about all the justice system stuff. So… that’s who she is, and she absolutely does have some authority and expertise to offer in the other lady’s life. Who is the other lady to keep ignoring and pushing back against her lawyer, actually? Race relations just got all mixed up into the lawyer-client relationship, which is kinda (one of) the point(s) of the book but also bothered me because it muddied everything and left me feeling dissatisfied with the ending. I would have liked more nuance with the role-reversal.

But back to the white supremacist thing. I just have to emphasize how difficult it was, at least at first, to read from his perspective, to give him space to develop without being super creeped out by being in his skin. I can see people DNRing the book at that point.

Otherwise, most people in my book club found the writing style to be approachable, easy to read. The twists kept the readers going. But it did get repetitive and in the end there was just too much included in the story. I agree that it felt written to become a movie. Some Picoult fans shared that they thought it was actually one of her worst books. It might have been inconsistent or unrealistic with some of the law stuff, but I don’t actually think we expect or need fiction to always be spot-on with reality. I also agree with the reader who said it “didn’t feel organic. More like some buttons had been pressed.” Which I think is akin to the other person saying they felt manipulated.

As a white woman, I do think I learned something while reading it, but not perhaps as much as the writer would have hoped. I mean, one of the book’s strong points is a “racist” character who looks just like you and me (oh white women of book clubs) alongside a more obvious racist. But I was annoyed by knowing I was being spoon-fed my medicine with the story, especially when it got cheesy or repetitive or, well, arguable/dubious (like the point above about an expert not being able to give advice to someone else because they have lived different lives (are different races)). I did think it was an easy read and I for sure wanted to know what was going to happen. I was at first impressed by the writing style, but it got long-winded, repetitive, and sometimes cheesy and also had a number of cliche characters (including the protagonist being a “palatable” Black woman instead of a more problematic and nuanced character).

The people in my group recommended three books that cover the same topics but are arguably better-written (the ratings are consistent with their conclusions, though Small Great Things also has great ratings.) One is The Violin Conspiracies by Brendan Slocumb (this novel does look really good), and Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter by Tom Franklin (another novel). There’s also The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones, a nonfiction collection of essays placing slavery at the center of understanding American history and American culture. Of course, there are many people who would read Picoult and probably not any of these other books, so perhaps Small Great Things is a good book to read for thinking and challenging, at least for the usual book club set. It is an easy read, at times riveting, and sometimes challenging or humbling, sometimes beautifully written. I just found it a bit draggy, overdone, and filled with too many cliched tropes. I did enjoy the read, though, once I adjusted to Turk’s POV (even though I wasn’t sure I should be adjusting to Turk’s POV). In the end, I felt it was worthwhile for having looked Turk’s character in the face and acknowledged the horrible things real people have done and are doing–as long as he doesn’t distract us or overwhelm the story of systemic racism.

If you want to know more about the award-winning and prolific author Jodi Picoult, you can find her website HERE. Many people consider My Sister’s Keeper to be her best.

“Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are” (p1, Benjamin Franklin).

“…how love has nothing to do with what you’re looking at, and everything to do with who’s looking” (p11).

“A mother has nine months to get used to sharing space where her heart is; for a father it comes on sudden, like a storm that changes the landscape forever” (p45).

“I knew that sometimes when people spoke, it wasn’t because they had something important to say. It was because they had a powerful need for someone to listen” (p118).

“If the first freedom you lose in prison is privacy, the second is dignity” (p176).

“As a nurse you learn how to make a patient comfortable during moments that would otherwise be humiliating …. As I stand shivering, naked, I wonder if this guard’s job is the absolute opposite of mine. If she wants nothing more than to make me feel shame” (p176).

“I may not have much to say here, but I still can make the choice to not be a victim. The whole point of this examination is to make me feel lesser than, like an animal. To make me ashamed of my nakedness. / But I have spent twenty years seeing how beautiful women are—not because of how they look, but because of what their bodies can withstand. / So I stand up and face the officer, daring her to look away from my smooth brown skin, the dark rings of my nipples, the swell of my belly, the thatch of hair between my legs” (p177).

“Pride is an evil dragon; it sleeps underneath your heart and then roars when you need silence” (p214).

“…what we strive for and get, we deserve. What I neglected to tell him was that at any moment, these achievements might well be yanked away” (p234).

“It is amazing how you can look in a mirror your whole life and think you are seeing yourself clearly. And then one day, you peel off a filmy gray layer of hypocrisy, and you realize you’ve never truly seen yourself at all” (p234).

“That if our legacy is not entitlement, it must be hope” (p234).

“…the reason we lose people we care about is so we’re more grateful for the ones we still have” (p241).

“If I was in the right, how come I couldn’t stop rehashing what I’d said?” (p255).

“But you know, you go on, right? Because what other choice have you got?” (p262).

“’You know the hardest thing about being a mom?’ I say idly. ‘That you never get time to be a kid anymore.’ / ‘You never get time, period’” (p267).

“’From where you stepped in, in your life, it looks like we’ve got miles to go. But me?’ she smiles in the direction of the girls. ‘I look at that, and I guess I’m amazed at how far we’ve come’” (p269).

“’Slaver isn’t Black history,’ I point out. ‘It’s everyone’s history’” (p282).

“’I got other friends,’ Rachel answered. ‘You’re my only sister’” (p284).

“I hear the flow of the fountain behind me, and I think about water, how it might rise about its station as mist, flirt at being a cloud, and return as rain. Would you call that falling? Or coming home?” (p290).

“The people you think are solid torn out to be mirrors and light; and then you look down and realize there are others you took for granted, those who are your foundation” (p340).

“It is remarkable how events and truths can be reshaped, like wax that’s sat too long in the sun. There is no such thing as a fact. There is only how you saw the fact, in a given moment. How you reported the fact. How your brain processed that fact. There is no extradition of the storyteller from the story” (p342).

“It’s crazy, isn’t it, that you can love a girl so much you can actually create another human being? It’s like rubbing two sticks together and getting fire—all of a sudden there’s something alive and intense there that did not exist a minute before” (p383).

“Micah clears his throat. ‘Radical thought number one: maybe you need to take yourself out of this equation’” (p396).

“Prejudice goes both ways, you know. There are people who suffer from it, and there are people who profit from it” (p408).

“For me, the dire consequence of that stoplight conversation was feeling snubbed. For him, it was something else entirely. It was two centuries of history” (p414).

“Does that make me a villain here? Or does that just make me human?” (p417).

“Equality is treating everyone the same. But equity is taking differences into account, so everyone has a chance to succeed …. The first one sounds fair. The second one is fair” (p427).

“There’s only so many things you can hate. There are only so many people you can beat up, so many nights you can get drunk, so many times you can blame other people for your own bullshit. It’s a drug, and like any drug, it stops working” (p443).

“How many exceptions do there have to be before you start to realize that maybe the truths you’ve been told aren’t actually true?” (p443).

“Maybe however much you’ve loved someone, that’s how much you can hate. It’s like a pocket turned inside out. / It stands to reason that the opposite should be true, too” (p443).

“People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love” (p453, Nelson Mandela)

A star-studded cast and crew was announced for the movie version of Small Great Things in 2017, but I see no news since then. It would make a good movie and be easy to adapt, but at this point it’s probably a no-go.

May 10, 2024

Book Review: The Paragon Hotel

I really hate doing this, but it’s so bad. Mine is not a universal opinion, not even universal in my book club (though it is also not unique). But while I was interested in what was happening and kept turning the pages, the writing style was just way too much. And the plot was all over the place, too. There were way too many themes or issues, which piled on all the way up to the end. The Paragon Hotel by Lyndsay Faye is not the only bad book I’ve read lately. I’m on a roll. But I will not be recommending it (or the others).

In the swinging 20s, Nobody is an Italian-American, young woman riding a train from the East Coast (Harlem) to the West (Portland). She’s been shot, but nobody’s supposed to notice that, until the Black porter does, and finds her help in segregated Portland’s all-Black hotel. She also comes with a suitcase full of cash and a complicated, secret backstory involving the Mafia. But The Paragon Hotel’s long-term inhabitants have complicated, secret backstories of their own, and when a Black child goes missing just as the KKK comes to town, some of those stories will be unearthed while violence and racism circle ever closer to all of them.

So, let’s start with something simple: the book is in present tense (the majority of it, anyway), first person POV. I prefer past and third, but I can accept other things if I feel like there is a reason and enough going on in the book to make the shift worth it. (Also, YA tends to be in first person. And present tense is a little trendy.) While Faye uses present tense to distinguish the main story from her backstory (told in frequent, chapter-long flashbacks), I was put off by it. And I also would have loved 3rd person so that we could get out of Nobody’s voice sometimes, which was overbearing in its 20s/cutesy/jargony presentation.

And that was probably my biggest problem with this book: the voice. Nobody (the character) is over the top. She’s funny and uses time-appropriate phrases and all, but it’s spread on much too thickly. Here. I’ll give you an example of when the humor and voice go right: “He looked like a fat woodpecker—if woodpeckers felt dreadfully awkward around Negroes, which so far as I know is an exclusively human characteristic” (p181). It’s goofy and unique, but at least it’s funny and comprehensible. There were many more times when I had to re-read sentences over and over to even figure out what Faye was saying. Why? Those sentences were twisted into acrobatic contortions, littered with jargon, riddled with metaphors (and mixed metaphors), and trying so hard to be funny and witty and unique. The metaphors thing bears repeating; Paragon Hotel is like a metaphor farm. Or where metaphors go to die. Here are a few examples of when the writing style failed: “The trio walked to the corner. Waited for me with slitted prison-gate eyes” (p183. What the heck are prison gate eyes?). Also, “We can’t see the moon sleeping high above the charcoal-sketched Portland streets” (p191. It’s like telling us not to think of a pink elephant). “He’s positively nailing the dandy act, violet cravat and a monocle, no less, because why pay the dairyman when you can buy the whole cow” (p195, just too much. Too much). While these little snippets might seem okay, string together a book of this writing and, believe it, it becomes overwhelming quickly.

Style aside, I didn’t mind that the tone of the book was strangely playful, like Life Is Beautiful mixed with The Godfather II. But then sometimes this approach went south and I found myself disturbed by the silliness at very serious moments, like, “It’s getting to be all I can do not to stare at her with tragedy beaming from the old peepers” (p253). And I did mind that Faye then shoehorned in so many issues. Like Life Is Beautiful was about the Holocaust, The Godfather II about the mafia. Paragon Hotel is about racism, organized crime, gender issues, sexuality issues, community violence, Prohibition, nightclubs, disease, mental illness, and family dynamics. With more than one thread related to each of these. Some of these stories appear to come out of nowhere late in the book. At least one of them drops off, basically unresolved. Because it’s too much and therefore stretched believability, especially given the time and place. (Not to mention that the book is framed as a “love letter” to someone. We forget we’re supposed to be figuring that out, too.) My book club had ideas about which plot lines and themes should have been cut, which included a counterfeit subplot. Some people thought that this could have been two books (Harlem and Portland), then it would have simplified matters enough.

The writing style also felt to me like I was reading a play. There was plenty to look at, but not a tremendous amount of depth, despite all that was revealed. Or like the deep stuff was cheesy, hokey. Some of the readers at book club tried to say it was confusing writing because it was confusing times, but we basically laughed that off. No, it was just confusing writing, and we don’t need to look for excuses. Some readers called it “too poetic,” but that’s not it, either, though I understand what they mean: like poetry, the meaning to the sentences was buried and needed to be extracted. But this is supposed to be fast reading. And it lacks many of the qualities of poetic writing.

Some have accused this book of having a white savior narrative. Is there nuance? Is there a difference between that paradigm and the one in the book where an injured, ex-Mafia lady lands in the middle of a mess and often bungles it up while trying to fix it? I mean, she’s definitely trying to fix the problems the Black community and its members are having in Portland. Is she working with them? Is she just an ally? Using her position in society to do things they couldn’t do? It’s a trope worth discussing regarding this book.

A few notes: there are some real characters, places, and events in this book, though mostly it’s made up. The Portland segregation laws are real, obviously. The hotel is based on a real hotel (The Arcadia). There is some real New York Mafia stuff going on (like the Corleones). Also, living in a hotel was much more normal at the time this book takes place. (There were some readers confused about this at group.) Just FYI.

And I was not the only one really perturbed by the misuse of the word “admired” on like every other page at the end of the book. What on earth happened here? I counted eight times.

Let’s end on this: the back of the book says that The Paragon Hotel is “A remarkable, significant novel” and a “wickedly poetic tour de force.” It credits it with “stunning prose” and says it is “exquisitely plotted.” Absolutely not. We laughed at these assertions at book club. But I will give it this: “Full of wry wit, dark humor, and magnificent period details.” Or at least a lot of period details because there was a lack of setting. I kept reading because I was committed to it and, really, you want to know what happens. Otherwise, it felt like a disappointment, a book I wanted so much to like but just couldn’t respect.

Lyndsay Faye definitely has some great ideas for books. The Paragon Hotel is actually among her lowest-rated, though they are all around the same space (3.8) except for the Timothy Wilde series (which are consistently rated over 4 stars). Here are her books:

The Gods of Gotham (Timothy Wilde #1)Seven for a Secret (Timothy Wilde #2)The Fatal Flame (Timothy Wilde #3)Dust and Shadow (Dr. Watson recounts Jack the Ripper story)The Whole Art of Detection (Sherlock Holmes stories collection)Observations by Gaslight (Sherlock Holmes stories collection)Jane Steele (murder mystery Jane Eyre)The Gospel of Sheba (part of the Bibliomysteries series)The King of Infinite Space (LGBTQ+ Hamlet in modern New York)Her website can be found HERE.

“That horse you’re beating needs burying” (p259).

“Because life is a circus. When you risk nothing or little, your audience is entitled to think little or nothing of your efforts…” (p262).

“Her apricot waves are piled atop her head, but it looks like she employed two minutes and a fork on the project” (p288).

“How does a body dare to dirty bedsheets when you know exactly who’ll be washing them?” (p336).

“What’s going on is that Blossom is trying to fight trouble with trouble, which I’m dreadfully afraid only leads to more trouble” (p340).

“Honey, if this is lucky, Christ save me from further serendipity” (p386).

“And I left to ponder how much you would have to love someone to give them up entirely” (p387).

“Blossom is probably correct—Jenny can’t change the world. But I wonder what a thousand Jennies, sitting at a thousand typewriters and punching millions upon millions of letters into straight columns, all those separate words in newspapers across the nation marching as one great force, might accomplish if given the means and the time” (p398).

“Let’s mourn only for our losses. And never for the things we haven’t lost quite yet. We already have an entire language that would be dead if you were” (p414).

May 9, 2024

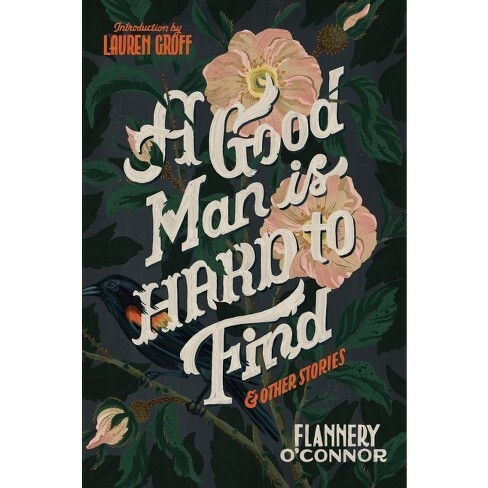

Book Review: A Good Man Is Hard to Find

A Good Man Is Hard to Find by Flannery O’Connor is bleak and difficult stuff. I was just drooling over it for its clarity, cleanness, style, innovation and trend-setting… but was dying inside due to its content. Satirical down to the word, nothing and no one in the world of the South in the early twentieth century is safe from O’Connor’s skewering, indeed, not one (horribly or horrifying) character escapes it. It’s a dark exploration of human nature and the human condition. And it’s literary gold.

A Good Man Is Hard to Find is a collection of short stories published during her time by O’Connor herself. They represent the best of what she was doing, at the time that she was doing it (published in 1955). It was an important piece of literature gathered from various important literary magazines and was popular in its time. It has become a classic, the stories and the book still read by students, studied by literary people, and an embarrassment in some circles if it hasn’t been read. O’Connor’s writing is nearly synonymous with Southern Gothic, and one can still tour her childhood home in Savannah, Georgia (I have stood on the stoop twice). The stories in this volume are classic O’Connor: pointed, clear, violent, tragic (depressing), harsh. And some say funny. I don’t see the humor, here.

It is entirely likely that you have read some O’Connor. Three out of four people in our house can remember reading the title story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” (it’s so memorable—though much more memorable when one says “The Misfit” instead of its given title). I have started reading O’Connor’s Complete Stories before, but did not continue after a few. Every American is supposed to read O’Connor (which sounds funny separated from her first name, like that, though her given name was actually Mary). I would say that if you are going to read O’Connor, yes, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is a good place to start, and you might as well read the rest of A Good Man Is Hard to Find while you’re at it.

I was glad that this was the book for April for my literary book club (which is often a classic). Since having given up on her complete works, I figured a book club would force me to keep pushing through the dark spaces of her stories. And it did and I did. And I certainly don’t regret it. Like I said, I was struck dumb by her writing style and how clean and clear it is. I was also taken with her ability to build tension—sometimes in mysterious, clandestine ways—and sustain it through entire stories. I was so afraid for everyone in all of her stories, but some characters really leapt off of the page with my anxiety there to meet them. I found themes running through the collection, like a frustration with ignorance, isolation and powerlessness, conversely power and control, and assumptions of morality. I was a little confused about religion in her work, though maybe she was too. (All indications is that she wasn’t.) She was a devout Catholic with very firm beliefs, but her work is full of hypocrisy and, well, predatory unrighteousness.

In the words of my book club, “she does not hold back.” Also, “she begins with a bang,” which is a funny pun referring to the first story, the “Good Man Is Hard to Find” I keep referring to. It’s a hard-hitting tale, and it does dive right into ideas of wrong and right and good people and bad people, exposing the “good ol’ days” for what they are: an illusion, while simultaneously giving us a crone of a character, a wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing role-reversal who we understand as inauthentic, hypocritical. Other comments from my group: that O’Connor has “amazing style” and “can show you what she wants to.”

I couldn’t stop thinking about O’Connor’s time compared to my own. There are universal truths, sure, but O’Connor’s world is dependent on the decency of the individual, and when the individual fails they blow up the world around them making victims of the people around them. We are now more dependent on systems than individuals but, let’s face it, they can both be corrupt and sometimes—often?—are. I mean, O’Connor’s stories are so violent. It’s not slasher horror, but a reader has to sit in unease as people fail spectacularly to live out their ideologies, completely mistaken about who they and their neighbor are, acting out of impulse and pragmatism and eventually imploding. There is also sexual tension in many of the stories, though I imagine that O’Connor’s lack of explicitness in this respect is simply due to the strictures of the times—if she could have, she would have. I mean, she did get away with a lot, as it is.

Which leads me to the big ol’ trigger warning: O’Connor refers to Black people with the vernacular and understanding of the white Southerners of her time. Even when she was stabbing at racism, which she certainly was, this was a different time. Don’t look for ideas or language that would meet today’s ideas of politically correct or progressive. (Yes, the n-word is used several times.) Look for a moment in history. And for some insight into race relations.

A Good Man Is Hard to Find is so full of clear writing that it took me until the beginning of the second-to-last story to have one moment of confusion. It’s Southern Gothic at its darkest and best. Some might call it tragi-comedy, even funny, but I found nothing about it a laughing matter though I found all of it to be a thinking matter. Dense. Rich in thoughts, history, and literary moments that will continue to teach us into at least the near future, O’Connor’s stories are true, American classics and a real, American treasure.

Note: my favorite story in the collection is “A Late Encounter with the Enemy.” I have my reasons, mostly thematic.

Another note: some suggested similar reading that came out of my book club was “Why I Live at the P.O.” by Eudora Welty, as well as “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” by O’Connor.

Flannery O’Connor was born Mary Flannery O’Connor in 1925. She lived most of her life in Georgia—she was born in Savannah but settled in Milledgeville. She actually started out as a cartoonist and went to Iowa’s and Yadoo (prestigious programs that are still looming large in the writing world) before being widely published. She died young of complications of lupus. Her life was generally quiet, spent mostly on the family farm with her mother. The pastoral and rural life is apparent in her writing.

O’Connor’s works are:

Wise Blood (1952 novel)A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955 short story collection)The Violent Bear It Anyway (1960 posthumous novel)Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965 posthumous short story collection)The Complete Stories (1971)Flannery is a 2021 American Masters documentary that won several awards and would definitely be worth watching.

“’Have you ever,’ Mr. Head had asked, ‘seen me lost?’” (p105).

“’All I got is four abscess teeth,’ she remarked. / ‘Well, be thankful you don’t have five,’ Mrs. Cope snapped and threw back a clump of grass” (p136).

“In those times, she said, everythihng was normal but nothing had been normal since she was sixteen” (p162).

“If she don’t get there before the dust settles, you can bet she’s dead, that’s all” (p179).

“Nothing is perfect. This was one of Mrs. Hopewell’s favorite sayings. Another was: that is life! And still another, the most impotant, was: well, other people have their opinions too” (p179).

“If you want me, here I am—LIKE I AM” (p181).

“You could not say, ‘My daughter is a philosopher.’ That was something that had ended with the Greeks and Romans” (p185).”’In that barn,’ she said. / They made for it rapidly as if it might slide away like a train” (p199).

There have been several adaptations of O’Connor’s work. Pertaining to this collection, there is a 1957 version of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” an episode of Schlitz Playhouse of Stars titled “The Life You Save” and starring Gene Kelly. It was the only adaptation O’Connor allowed and was very disappointed in it. I understand that it is not loyal to the original material.

There is also a 1977, one-hour adaptation of “A Displaced Person,” Displaced Person with Samuel L. Jackson. It is supposed to be much better than the previous, but maybe not awesome. It was shot on O’Connor’s family farm, Andalusia, though, using many of the historic props, so that is really pretty cool. I wouldn’t mind trying to hunt this one down.

There’s a 1976 version of “A Circle in the Fire,” 1975 “Good Country People,” and 1976 “The River.” Many or even all of these might be hard to find or prohibitively expensive to acquire.

May 6, 2024

ARC Review: The Marriage Sabbatical

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comIf you had told me several years ago that I would start reading romance novels, I would have scoffed at you. While I read nearly every genre out there, there are some genres that I just don’t. (Okay, so I always make exceptions for great literature, no matter the genre—I guess unless it’s too hard core.) Until a few years ago, this banned-genre list included romance. I mean, I read classic romance and plenty of books with romance subplots, but not the stuff that you find splashed across table displays in big bookstores or crammed creased-spine to creased-spine in used bookstores in the section prominently labeled “romance.” Perhaps it was the dawn of the fun, colorful, cartoony covers that helped me make the transition (as opposed to dull, dark, photo covers with bare-chested athletes being embraced by manicured women in loosening bustiers). Like something between women’s literature and old-fashioned trade paperback romance, the new romance books I was seeing didn’t have to be boddice rippers. And they could be well-written (enough). Which is how I met my first Emily Henry novel. And how I began the tradition of reading a “light” (almost always romance) novel while on residencies and vacas.

That’s a long introduction to a book that I have yet to mention. Sorry. But I did it to make two points. One, I do read this genre sometimes, though I am extremely picky about it. And two, I am not actually a romance reader, as in I would never make my username romancereader743 or normally head straight for romance lists or sections. I have limited experience in the genre. And I made those points to say this: The Marriage Sabbatical by Lian Dolan is, from what I can tell, on the good end of the romance writing spectrum and is going to appeal to and be enjoyed by lots of modern women (maybe some men?). It’s clear and full of cute characters and interesting places—has a great premise—and a few almost-steamy scenes. It also has the women’s fiction thing going on with some sort of moral and positivity and feminism-ish thinking. Readers seem to consistently like Dolan, and Marriage Sabbatical has already become a bestseller (since its release less than a month ago). But it turns out it is not quite my cup of tea.

Jason and Nicole met in college when their two, very different worlds collided one fateful night over a shared, musical tragedy. (Like, where were you when…?) Now it’s more than a quarter of a century later and they have made those two worlds into one, survived some real ups and downs (in-laws, careers), renovated a Portland home, and raised two kids. Right after those two kids head off for post-grad experiences abroad, Jason and Nic end up being pinned down for a dinner with their new neighbors and their TMI, which includes the revelation that they have a 500-mile rule: more than 500 miles from each other and they can have sex with whomever they want, no questions asked. Days later, when Jason and Nic find themselves unexpectedly facing nine months on two different continents, they make a deal with each other that is much closer to those ridiculous neighbors than they would have thought possible…

It took me a minute to get around to reading this, as it has taken me some time to get to any and all ARCs I have taken on this year. Which is hugely the fault of me joining six-plus book clubs. Yeah, that’ll do it. Also to me being ADHD. Sorry.

Here’s the thing: the premise is sexy in a seriously modern way. It’s sensational, a draw for the book. But the real story here has little to do with sex and everything to do with a realistic marriage and a pretty average couple. Which means the sex-rule will make people pick up the book and take it home (while causing many people to also pass it over–I am 100 per cent sure). But the whole sex thing literally didn’t even need to be in the book. The couple in question are dealing with other things, entirely: Jason is dealing with grief and simultaneously a much-deserved vacation and mid-life crisis; Nicole is dealing with an empty nest and an identity crisis, discovering who she is without kids (and a husband) and re-discovering her dreams and passions. The sex got thrown in there to make the plot more interesting. It’s so not about that, though.

And then you end up with readers like me, who just wish it wasn’t there. I don’t really get the appeal of opening a marriage and I found myself annoyed at their sexual experiences (or lack thereof) apart, feeling like they needlessly complicated matters, playing with fire when they totally intended not to burn anything down. In other words, I am too old and experienced to believe that this whole sitch would work except in rare and random cases. Why gamble when you have everything to lose and almost nothing to gain? I’m too practical. And it turns out, old fashioned. (Don’t worry, fidelity’ll come back in, ‘cause it rules. And it is a type of turn-on, a type of romance itself.) The only thing in me that wanted this part of the plot to stay was the one that enjoys the challenging of cultural constructs that have been too restrictive. Because they have done a lot of harm, and I enjoyed thinking about how things might be different and how people’s business is none of our business. (Likewise, being all self-indulgent and flaky will also cause a lot of harm to the next generations. The pendulum continues to swing and it will forevermore.)

But who cares, right? The point is an interesting, fictional book. Which leads me to another reason this book was not my thing: it is so, so very fantastical. Yeah, the characters, places, lives lived were recognizable, even relatable. But there was always a bridge too far, like in every scene, and I stopped being able to take it. They just had so much money. And perfect friends. And they worked out every day. And had all the things. And their kids were both studying abroad but they could afford a sabbatical. And his work was cool with that. And all the supporting characters said and did all the things right. And people always said their honest feelings. And emotions didn’t get all caught up in affairs. And everything was tied up with a giant bow. I am also sure that many readers will love all of this, because, yes, romance is often extremely fantastical. It is supposed to be. Romance readers usually want to be whisked away to some other place where things are perfect and sexy and, duh, romantic. But not me, I guess. At least, not in this way. It was more eye-rolling than enticing or, well, dreamy.

And it’s true that I said the writing was clear. The book was produced well, too. Edited well. Did all the things. But between the writing style and the lack of drama, I was a little, um, bored. It was too cozy and too straight-forward for me. But other people love cozy. And other people don’t want to read poetry or have to work for the narrative. Sigh. I get it. There is a place where the grass is greener and a happy medium is met. Emily Henry is on the outskirts of this place. I have a whole list of recommended books that I feel land in this space and a few of them are probably considered romances. Book club reads. Women’s literature.

I would recommend Marriage Proposal for plenty of people. I would not recommend it for myself (which is a moot point, at this point, or maybe I mean impossible, or anachronistic).

I want to talk about Georgia O’Keefe for one second, before I let you go. I don’t think it’s an accident that Nicole ends up in New Mexico nor that she takes us to an art world that includes the art of and references to Georgia O’Keeffe. I mean, Dolan talks about it directly in the book, but O’Keefe lived in two places, in her marriage, and she supposedly kept her life in New Mexico separate from her marriage in New York. From what I understand, O’Keeffe was in what had become (at least) a toxic marriage in a very patriarchal time. Also, it seems that when this stage of their marriage was in full-swing, it wasn’t really much of a marriage anymore. It is cool to see a strong-willed woman carving a life out for herself at a distance from the husband who is stifling and likely abusing her as well as distancing her career from his. But while it makes sense to bring this story into Marriage Sabbatical as a thread, their situations appear to be vastly different and there was no going back for O’Keeffe.

I also want to point out a book which kept coming up when I was looking around on the internet for stuff about Marriage Sabbatical. It’s a book by the same name, but with a subtitle: The Marriage Sabbatical: The Journey That Brings You Home, by Cheryl Jarvis. It is a nonfiction book published way back in 2002, a sort of memoir and self-help book that contains 55 women’s stories about taking time away from their marriage in order to find themselves or pursue a dream. Looks kinda interesting. I don’t know if any of them have anything to do with opening their marriage, but I can’t imagine all of them do.

This book was easy to read. It delivered on several fronts: it was sweet and interesting and went down smooth. I could relate to it in many ways and wanted to know where it was headed and what was going to happen; I mean, even the hook of a premise got me. In the end, it wasn’t my fave. I was a little bored and a little too jaded to get sucked into the story. Also, the open marriage idea was a turn-off for me and for whatever reason I did not find the (few and mild) spicy scenes to be spicy, at all. But I can see how many readers would enjoy this book and it’s a safe investment of your time if this kind of book is what usually speaks to you: a cozy, women’s lit kind of romance without too many literary trappings.

Lian Dolan is a writer and podcaster. She is one of five sisters who have a women’s, talk-show podcast (that began as a radio show) called Satellite Sisters. She has also written articles for various mags, including O Magazine. Her website can be found HERE.

Her books, which look to be all romance, have reviews that hover right below 4 stars, consistently (which is not at all bad). They are:

Helen of PasadenaElizabeth the First WifeThe Sweeney SistersLost and Found in Paris

“This isn’t a midlife crisis; this is a midlife triumph” (p180).

“Her friends were here to see her, not judge her” (p187).

“…he found no conversation among his parenting peers more tiresome than college acceptance. There was a place for everyone, even if it didn’t rank in the top ten. Why his generation of parents found their own self-worth in their child’s ACT scores or college acceptance record, he’d never understand” (p205).

“I think it’s so foolish for people to want to be happy. Happy is so momentary—you’re happy for an instant and then you start thinking again. Interest is the most important thing in life; happiness is temporary, but interest is continuous” (p233).

“Those Gen Zers, they don’t care about precedent or hierarchy. It’s relationship anarchy out there” (p256).

“Was that a sign of aging? The desire not to fuss? He was losing his edge” (p257).

Book Review: The Astronomer

The Astronomer by Brian Biswas is several things. It is a magical realism-verging-on-speculative novel, though it is comprised of short stories that have been strung together and bracketed with other short stories that give a Victorian-style faux-outsider perspective. The story (which contains everything from Greek mythology to existential considerations) is told in short bursts that are more emotion than plot, even though the text is riddled with science and real places and times (and even at least one real person). But the plot makes it a story of (lost) love and pain wrapped in a couple other-POV chapters that attempt to tell us the truth of the thing. Then again, none of the POVs are completely reliable, or so I think. It’s an incredibly calm book. Two readers can walk away from this book with different readings, different realities, but each of them will be thinking.

From the back of the book: “Franz Herbert suffers from epileptic seizures; are they a curse that takes him away from his wife, family, and friends, or a gift that allows him to explore the depths of the cosmos?” In a slim volume (252 pages), we jump back and forth between Franz’s supposed history (from the 1920s to the 70s) and his trips into outer space to explore the astronomy he studies at work in a way no one else can study it—first-hand. Surely his spaceship to Pluto is just an epileptic episode. But it’s real enough to threaten what the people around him call “real.” Or is everything in Franz’s head?

As Dumbledore says (in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows) when Harry asks if his near-death experience is in his head, “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean it is not real?” Though I highly doubt that Biswas has read any Harry Potter, this quote is basically the thesis statement for The Astronomer. You’ll want to start the book with reading the Prologue, because you’ll soon learn that a major part of the reading experience here is to decipher what is actually happening (in a fiction universe, but you understand what I mean) and what is part of Franz’s disease. (And what is wrong with him? And who is part of his real world and who his fantastical?) And then, inevitably, you’ll have to ask yourself if it matters which is which (and also who it matters to.) Is the space (pun) inside people’s heads (or their dreams) just another type of reality? And do we have to distinguish between them so religiously?

After reading the book, I wasn’t totally sure what was what. Then I went to a book club where the author spoke, and I am a little more sure about the author’s intentions, but I am also more sure that Biswas would like me to come to my own conclusions, indeed, that he doesn’t feel himself the ultimate authority on what the “truth” of the text is. Did Franz have epilepsy (as the back copy would have us immediately believe), or was he an alcoholic with a traumatic brain injury imagining the seizures into his past? Or both? Who does or doesn’t exist? Does his son even exist? Is the second-to-last chapter the final word or just another case of an unreliable narrator? Are even the lies a lie? Does Biswas even care if we figure it out?

I think a good place to begin with this book would be to learn a little astronomy and a little history of astronomy. I have been interested in astronomy my whole life, so I already knew some things (including from my college Astronomy class). However, understanding who Clyde Tombaugh is and about the discovery of Pluto could really give the reader a ton of clues as to where Franz ends and his imagination or hallucinations begin. I’ll give you the super-short version: Tombaugh was a farmer and amateur astronomer who built home-made telescopes and a makeshift observatory in his back yard and was employed by Lowell Observatory for 20 years after sending them drawings (and then he did go to school, too). He discovered Pluto (the first object observed of the Kuiper Belt) and a number of asteroids while he worked at Lowell. He was also famous for seeing a series of UFOs in one night, and while some people have said he saw “spaceships,” Lowell was overwhelmingly in favor of an impossibility of extraterrestrial, intelligent life and thought the sighting was likely an atmospheric, optical phenomenon. Still, all this info plays out in the book. So pay attention.

Another interesting thing to consider before reading The Astronomer is that Biswas was inspired by himself in writing it. He had experiences with seizures when he was 14 and some of the details were written in to the book. However, the seizures faded for Biswas, while the idea of Franz, the character, haunted Biswas insistently for decades until he finally wrote him out (first in short stories). Or maybe that doesn’t matter to you. I enjoy info like that when I’m reading and trying to put a story in its context, understand writer-intent (which does matter to me, though I suppose it’s not the be-all end-all).

I do have a small stake in this book, just FYI. Biswas was the friend/co-worker of a friend/co-writer of mine who passed away a few months ago. I was introduced to him by her at a reading of The Astronomer last summer, the last time that I saw her essentially healthy, in fact. I bought the book at the reading, happy to support a local author but also very curious since I love magic realism, thought the premise of the book was really interesting (combining health/mental health with magic realism), and I enjoyed Biswas’s voice as he spoke to us. I decided to read the book when a nearby book club scheduled it, and when I showed up for the club, there was Biswas. First of all, that was a really cool way to discuss a book: with the author right there. Second, I say all this to let you know I may not be totally unbiased with my review. I have a connection and experiences. But don’t we all?

If you like to read magic realism or you have an interest in astronomy, those are both great reasons to give The Astronomer a (pretty quick) read. There is a lot to consider here, to wonder about and puzzle out. Or you could just let yourself ride along on Franz’s trippy adventures, unconcerned about some silly thing like facts.

Brian Biswas is a Chapel Hill writer. He has had sci-fi shorts (some of which became The Astronomer) in Skive Magazine, Perihelion, Penny Dreadful, Iconoclast, Lost Worlds, and The Café Irreal, among others. The Astronomer is his first novel. He has two collections of short stories and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His website can be found HERE.

Here are some of the things he said at the book club meeting that I jotted down:

As a writer, you don’t get to choose your audience. You don’t know who they’ll be or what they’ll “get”“So much of writing is subconscious.”One of the hardest things you do as a writer is to cut what slows the plot.Writers must develop a thick skin, or they give up.When you write, you’re creating something that never existed before.

“You could be here. You could be there. And in reality you’re neither place—or rather, you’re in both places simultaneously. Twilight worlds that flash in and out of existence” (p12).

“No physical object can travel faster than the speed of light, but the human mind can and often does” (p51).

“I am composed of subatomic particles that wink in and out of existence. I am oblivious to reality much of the time. I don’t know why Isabella didn’t leave me long ago. She must love me more than I ever imagined. More than I deserve. I am a half-husband” (p54).

“…could we travel to these civilizations—given the bounds of time and space? / All that’s needed is the right fuel, I maintain, which is dependent on the civilization type. For a Type Two civilization it would be feasible, for a Type Three it would be child’s play” (p161).

“True love is not to be confused with infatuation which, though true, does not endure” (p196).

“But in our haste we discover too late we have misrepresented the problem, misstated the goal. It was not love but the fulfillment of our own desires that we were after” (p196).

“’In a very real sense, there’s no such thing as Time. You know this intuitively—sometimes the days pass fast, sometimes slow—though intellectually it is a concept few can grasp. We seem ruled by time, though we are not” (p213).

“Who are they but two Charons to guide me across the river to Hades which lies on the other shore?” (p231).

May 2, 2024

What to Read in May

I think we’ll wait a month to come out with our summer reading list, though that may be a mistake. Look for that in a few weeks. For now, we’ll wrap up the school year and the more-unpredictable weather with Mother’s Day suggestions and a number of books-to-movies and books-to-series.

We’re gaining on halfway through the year (okay, a third), and there have been some books that I have noticed simply everywhere. I won’t list them all here, partly because they have largely been on my recommendations lists. But I will mention a few.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comA Court of Thorns and Roses, Sarah J. Maas. I hear about “ACOTAR” everywhere, and I think it’s time to start the series if you haven’t already. My plan is to read this fantasy series before her also-super-trendy Throne of Glass series. The bookstore I am in most has a hard time keeping copies of these on the shelf. Like seriously, they are always selling out.

Tom Lake, Ann Patchett. This was one of the most celebrated books of 2023, and I still hear about it and see it around all the time. I’m pretty sure every book club will get to it, eventually.

The Travel Book and Epic Hikes of the Americas, Lonely Planet. It might be where I sit for book clubs in bookstores that keeps drawing my eyes to these books, but they look like amazing coffee-table books for travelers, or just travel-dreamers.

Have a Beautiful, Terrible Day, Kate Bowler. Like Chicken Soup for the Soul, but I’m guessing a lot edgier and more up-to-date. People are loving this book of insight.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comBook-related jigsaw puzzles, of which I am mainly thinking of Ridley’s 50 Must-Read Books Bucket List (also a Travel Destinations and 50 Must-Watch Movies) and Bibliophile’s Banned Books. There are also many other options out there.

As for Mother’s Day, I went with titles I haven’t yet read, maybe thinking of myself on Mother’s Day and what I would like to be reading. I pulled several of these ideas from my own online search of Mother’s Day reads and suggestions from other articles and Google. The first two are mom-themed. The others? Not so much, but they cover some different genres for different moms:

The School for Good Mothers, Jessamine ChanMother-Daughter Murder Club, Nina SimonMiss Eliza’s English Kitchen, Annabel AbbsThe Glass Hotel, Emily St. John MandelNight Watchman, Louise ErdrichThe Witch Elm, Tana FrenchThe City We Became, N. K. Jemisin

The School for Good Mothers, Jessamine ChanMother-Daughter Murder Club, Nina SimonMiss Eliza’s English Kitchen, Annabel AbbsThe Glass Hotel, Emily St. John MandelNight Watchman, Louise ErdrichThe Witch Elm, Tana FrenchThe City We Became, N. K. Jemisin

I keep hearing and seeing ads for the new The Sympathizer limited streaming series (Max) that has already started to drop (and continues once a week). I have been meaning to read this Pulitzer novel (Viet Thanh Nguyen), so maybe this is the moment. Though some books are okay to skip and go straight to the movie (like, ahem, the Bridgerton series), some I will make sure I read first. (By the way, most of these series below get crazy-great reviews.) Speaking of books-to-movies and books-to-series:

Dark Matter

, Blake Crouch => Dark Matter, Apple TV+ (May 8)

A Man in Full

, Tom Wolfe => A Man in Full, Netflix (May 2)

Dragonkeeper

, Carole Wilkinson => Dragonkeeper, theaters May 3)

Romancing Mr. Bridgerton

(Bridgerton #4), Julia Quinn => Bridgerton season 3, Netflix (May 16)Garfield series, Jim Davis =>

The Garfield Movie

, theaters (May 24)

Robot Dreams

, Sarah Varon => Robot Dreams, theaters (May 31)

The Idea of You

, Robinne Lee =>

The Idea of You

, Amazon Prime (available now)Manhunt, James L. Swanson => Manhunt, Apple TV+ (available now)

If It’s Not Impossible…

, Barbara Winton => One Life, various streaming (available now)

The Three-Body Problem

, Cixin Liu =>

3 Body Problem

, Netflix (available now)We Were the Lucky Ones, Georgia Hunter =>

We Were the Lucky Ones

, Hulu (available now)A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles => A Gentleman in Moscow, Paramount+ (available now)

The Talented Mr. Ripley

, Patricia Highsmith =>

Ripley

, Netflix (available now)Shogun, James Clavell =>

Shogun

, Hulu (available now)Dune, James Herbert (Dune: Part Two) => Dune, Part Two, theaters (out now)

Dark Matter

, Blake Crouch => Dark Matter, Apple TV+ (May 8)

A Man in Full

, Tom Wolfe => A Man in Full, Netflix (May 2)

Dragonkeeper

, Carole Wilkinson => Dragonkeeper, theaters May 3)

Romancing Mr. Bridgerton

(Bridgerton #4), Julia Quinn => Bridgerton season 3, Netflix (May 16)Garfield series, Jim Davis =>

The Garfield Movie

, theaters (May 24)

Robot Dreams

, Sarah Varon => Robot Dreams, theaters (May 31)

The Idea of You

, Robinne Lee =>

The Idea of You

, Amazon Prime (available now)Manhunt, James L. Swanson => Manhunt, Apple TV+ (available now)

If It’s Not Impossible…

, Barbara Winton => One Life, various streaming (available now)

The Three-Body Problem

, Cixin Liu =>

3 Body Problem

, Netflix (available now)We Were the Lucky Ones, Georgia Hunter =>

We Were the Lucky Ones

, Hulu (available now)A Gentleman in Moscow, Amor Towles => A Gentleman in Moscow, Paramount+ (available now)

The Talented Mr. Ripley

, Patricia Highsmith =>

Ripley

, Netflix (available now)Shogun, James Clavell =>

Shogun

, Hulu (available now)Dune, James Herbert (Dune: Part Two) => Dune, Part Two, theaters (out now)This month, we’ll see a number of publications in plenty of time for summer reading. Here are a few of the most-anticipated of them:

Last Murder at the End of the World, Stuart TurtonYou Like It Darker, Stephen King (book of short stories)The Honey Witch, Sydney J. ShieldsWhen Among Crows, Veronica RothThe Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley

Last Murder at the End of the World, Stuart TurtonYou Like It Darker, Stephen King (book of short stories)The Honey Witch, Sydney J. ShieldsWhen Among Crows, Veronica RothThe Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley

So, I am still in six book clubs, but only for one more month (because I already bought the books before I decided which two I was going to quit, though one club isn’t meeting this month, so there’s that too). Also, I am temporarily joining one group because it’s “up at the corner” and I was already aiming to read the book soon. Here’s what I’ll definitely be reading this month:

She Drives Me Crazy, Kelly Quindlen (YA for Adults book club)

Animal Farm

, George Orwell (Literary Reads book club)

1984

, George Orwell (Literary Reads book club double-dip)Trust, Hernan Diaz (guest appearance book club)The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula K. Le Guin (Speculative Fiction book club)Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer (Contemporary Reads book club)Empty Theatre, Jac Jemc (Local Bookstore book club)

She Drives Me Crazy, Kelly Quindlen (YA for Adults book club)

Animal Farm

, George Orwell (Literary Reads book club)

1984

, George Orwell (Literary Reads book club double-dip)Trust, Hernan Diaz (guest appearance book club)The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula K. Le Guin (Speculative Fiction book club)Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer (Contemporary Reads book club)Empty Theatre, Jac Jemc (Local Bookstore book club)

And my son will be reading Born a Crime by Trevor Noah for school. I loved that book and I hope he’ll discuss it with me.

Yikes. I had a bit of a slump month. Actually, month and a half. These are the only two books that I read that I could possibly include on a list of “bests”:

A Good Man Is Hard to Find, Flannery O’Connor, which I was just drooling over for it’s clarity, cleanness, style, innovation and trend-setting… but was dying inside due to its content. I mean, if you’ve read O’Connor—which many of you have—you’ll understand. It’s bleak stuff. Difficult stuff. Tons of satire where no one in her world is safe from skewering.

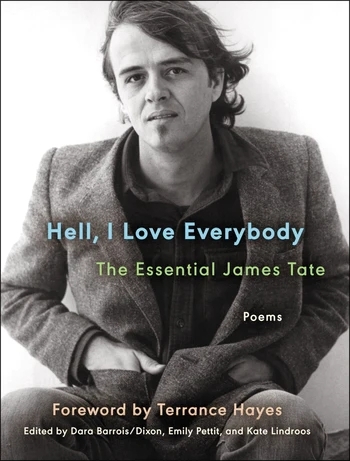

Hell, I Love Everybody by James Tate is a book of poetry, which means some of you are already out. It’s actually a carefully-curated, posthumous volume of his work, its slimness not giving away how many hundreds of poems he had published during his lifetime. It’s absurdist (and therefore often metaphorical or just beyond straight comprehension) and sometimes funny and probably meant to be enjoyed without having to rip it apart for meaning, too much.

April 24, 2024

Poetry Book Review: Hell, I Love Everybody

Sure, a fever dream. Absurdism, related—in time and space and feeling—to DeLillo’s White Noise, which I read last month. But sometimes clear, or clear enough. Hell, I Love Everybody: The Essential James Tate was not a collected book of poetry like I would expect. I mean, its meanings were hidden enough (sometimes so deep I did not bother to dig further for them), but these poems are not achingly beautiful or even heavy with saturated object-ness, if that makes sense. Not technicolor. In fact, Tate often wanders into dialogue and into prose-poem-territory. I appreciated the book. I think older people would probably find (or found) more footholds in his stuff, more places to relate to Tate. But it’s still interesting poetry, still well-written, as least in the moments where I didn’t feel out of my depth as a reader and reviewer.

James Tate was a well-loved and well-lauded freeverse poet who was published at 23 and kept writing and being a poet until he died in 2015. Hell, I Love Everybody is a slim collection of Tate’s most beloved poems (though not at all comprehensive), recently published, kicking off with a poem titled “Hell, I Love Everybody,” a quote from a laid-back Jesus. The poems are no longer than three small pages a piece, full of trippy characters and nonsensical interactions woven with meaningful musings and jump-off-the-page turns of phrase. Many of the thoughts end at conscious-adjacent; the shadow you’re left with instead is emotion: fear, revulsion, sadness, nostalgia, confusion, wistfulness, wonder…

It is poetry month. I gave you some recommendations at the beginning of this month and told you that I would be reading a new collection of classic James Tate with one of my book clubs. I had never read James Tate (that I could remember). (During the month, I happened to acquire a few more books of poetry, And Yet Held by T. de los Reyes, What Pecan Light by Han Vanderhart, Lovebirds by Hananah Zaheer, and If We Had a Lemon We’d Throw It and Call That the Sun by Christopher Citro. They are all small, indie books that I will be reviewing for you eventually.)

The foreward in this book describes Tate’s poems in this way: “He was a ventriloquist and witness.” It also uses the words bizarre, mythic, absurd, quotidian, diurnal, surreal, and sometimes nightmarish. There are only enough poems to read one a week for a year, but it is a carefully curated (three years of thought and debate) book of “beloved favorites.”

It is often more prose than poetry (even sacrificing lyrical beauty for content and for a point (like repeating the same line till the bottom of the page)), some (absurd) storytelling, and even repeat characters (and phrases such as “hell,…”). Lots of conversations with fantastical things and animals. Tate uses stand-in words frequently (felisberto, mergatroid (which came first, the Tate poem or Yogi Bear?)), like a Lewis Carrol poem. Even gets to sound Shel Silverstein at times.

While there’s a genius to the foreward by Terrance Hayes (in how very James Tate-ish it is—What’s real? What’s the truth in fiction clothing?), I would have liked some clarity and straightforward exposition in the book to anchor my thoughts. Also, I find it mystifying that there is not one lick of biographical info between the covers, as if an About the Author or short bio—or even mentioning anything about the man in the foreward—would have broken faith with the James Tate club that this book seems to be compiled for. Honestly, it just would have helped me understand if allusions were before or after (were the poems referencing something else or was life referencing them?) and what historical events and cultural markers Tate was writing about. His contemporaries had that much at least when they were reading the poems (and short stories) the first time: it’s not something that was meant to be hidden, guys.

My favorites from this book are:

“Never Again the Same”“Toads Talking by a River”“The Bookclub”“Of Whom Am I Afraid?”“A Largely Questioning Article Offering Few Answers”“The Ice Cream Man”“The War Next Door”So with a little understanding that you’ll have to come to on your own, you can probably trip your way through these poems either in an afternoon or in 52 trips to the bathroom. Or read one a week for a year and then go to the James Tate site and poke around, notice that the poem index has hundreds and hundreds of poems, look for a few of his recorded readings on the internet, consider listening to the poems in the car…

James Tate was an American poet. He came out of the Iowa creative writing program, was published early, and was a poet through and through. He won some top awards, including the Pulitzer, the William Carlos Williams Award, and National Book Award. He taught in an MFA program and ended up with 19 volumes of poetry and other books that included one (co-written) novel. He was born during WWII and it looks like his dad died the next year in the war. Tate died in 2015.

“You are the stranger / who gets stranger by the hour” (p7, “Consumed”).

“We are playing the same song and no one has ever heard anything” (p10, “Read the Great Poets”).

“They get home. That’s all that matters to tme. They get home. They get home alive” (p10, “Read the Great Poets”).

“’Frogs in the Dark, Lily / pads in the Dark, Pond in the Dark. Just as / many things exist in the dark as they do in / the light’” (p22, “The Painter of the Night”).

“’You regret / everything, I bet. You came here / with a crude notion of righting / all that was wrong with your own / bitter childhood, but you have become / your own father—cruel, taunting— / who had become his father, and so on’” (p28, “Worshipful Company of Fletchers”).

“I thought it was going to be / an awful party, but I just told the truth whenever I was spoken / to, and people thought I was hilariously funny” (p34, “The Formal Invitation”).

“The wind makes a salad / of the countryside…” (p84, “Pastoral Scene”).

“…the / river is a truck in / a hurry” (p84, “Pastoral Scene”).

“Danger invites / rescue—I call it loving” (p93, “Rescue”).

April 23, 2024

Book Review: A Million to One

This won’t be a long review. I don’t have that much to say about A Million to One by Adiba Jaigirdar. Just in and destroy and out. I jest. But do I? I did not like this book and I did not think it was well written. That’s the nice way of putting it.

Josepha has run away from home and landed in Ireland, taken up a life of petty crime. And now she has her sights set on a theft that will make her free and self-sufficient forever, not to mention that convincing three of the other girls in her boarding house to pull it off with her will get both her and her best friend closer to their relationship goals. The catch? The valuable object will be on the Titanic when it sets sail in a few days.

So, you’d think it would be a heist book. That’s what lots of reviewers say. And the publisher. But it’s not, not really. Though the plot is loosely and officially a heist, it lacks many of the elements important to a (successful) heist novel, so you may want to just throw that idea away now before you are (very) disappointed. Also, it is a historical novel. But the POV is so close into the (too many and underdeveloped) characters, that we fail to learn things about the time and place and we are never actually put into history, into any setting at all. In fact, if you don’t already know the history of the Titanic’s one ill-fated voyage, you are going to have a very hard time understanding some of the scenes and action sequences. It’s also a sapphic romance novel. But the romances are abbreviated, forced, and obvious to the point that you end up reading climactic scenes with the emotional involvement of a dead fish. It’s YA, but it reads (on every level: word choice, tone, internality, depth…) like it’s meant for upper elementary school/middle grades even though the content is older. So it has no genre? Well, no. Fine. It’s a historical, sapphic, romance, YA, heist novel. But it misses everything single thing it is trying to do.

I do actually hate to do that to an author. But I believe Jaigirdar has sold plenty of copies and has built herself a moderately successful authorial career. I’m just calling it how I see it (and how every other person in a rather large YA book club sees it): this one sucks. While the Land of Stories series still holds sway at the top of my worst books list, this one isn’t far behind. So harsh! Well, so many people in the book club were so excited about the potential of this book, but not one person could really justify it. Harsh for us, too.

I’ll break it down, just real fast: Full of cliches. Stakes weren’t high enough. Boring. The girls were terrible thieves and made horrendous decisions. I didn’t believe the sparks. I wasn’t nearly invested enough. Tension was mostly created by the Titanic and the history we already knew. Writing not great, editing not great. Maybe most importantly, was written as if for a MG audience when content and target audience was YA. Lots of telling me how someone was feeling or justifying why they did something, not showing. Nothing except the concept and the history worked for me with this one. I really forced myself through it, pausing to laugh out loud at especially ridiculous moments, like when one of the girls is suddenly a better engineer and more intimate with the Titanic than anyone else in the world at the time, or when one of the girls goes into a room as she’s running from the rising water to find a stranger’s dress and change into it. Cuz she’s wet.

And I’ll give you the book club break-down, too, real fast: (some things are repeats) not really a heist, just a bunch of bumbling scenarios, not-funny physical humor, and running around the ship like Scooby-Doo. (Not to offend Scooby.) Nothing holds up when you look too close. “The only part of this book that wasn’t a plot hole was the boat sinking.” Lacked description and sense of space. Rushed. Quick. Choppy. Written to MG level and style. Heists have to have very adaptive and smart characters, neither of which these were. Way too many POVs. “You have to put the Titanic in a book about the Titanic.” Romance and death happens, and you’re like what? No emotion. The seriousness needed in the girls’ backstories was utterly and completely lacking. The one positive: the sapphic romance didn’t end in one dead and one alive, which is apparently a persistent trope.

Literally every other book Jaigirdar has written has better reviews. Some of the people in club who have read others said she should maybe just stay far away from historical fiction. And heists.

I don’t even think we need a conclusion here. Just read something else of hers, or something else altogether. May I suggest A Night to Remember, by Walter Lord?

Best Books List: ADHD

One of the trends I see on social media is ADHD. Since the Pandemic, especially, many adults have been diagnosed with ADHD (especially women) and they are coming to terms with these diagnoses with memes, reels, articles, and books. Yes, the book market has risen to the challenge, and I find myself suddenly overwhelmed by the number of titles of books that didn’t seem to exist a handful of years ago. Also, with information: specifically, regarding women with adult ADHD and how this is different than other people with ADHD. I have long understood this, having been a girl and then a woman with ADHD myself—that my ADHD didn’t always look like what people expected because I wasn’t a rambunctious, misbehaving middle grades boy. (Not that middle school boys always look the same with their ADHD, but it’s much more common to play out that way… and much more obvious when it does.)

I actually have three chronic diagnoses that affect my daily life, every single day. The problems with my lower spine (degenerative disc, arthritis and scoliosis, which is related to tight hamstrings, if you can believe it) I manage pretty well. Cuz I can, at least till I’m old and it’s beyond the same control. As for migraine, unfortunately I cannot read about or even discuss it much without actually getting a migraine, so I’ve limited my research to lots of field research based on tidbits of info over a lifetime. Mischief mostly managed, but much daily discipline needed. As for ADHD, I felt restricted to experimentation here, too, for most of my life, because (like migraine) the general population and specialist understanding of my problems and my struggles were very small and knowledge about them have only grown in quality and quantity, significantly, in my adulthood. And ADHD was much more insidious: I am only beginning to realize how much ADHD affects my happiness as well as my functionality on a daily, no, hourly, no, minutely basis. How much peace and joy it robs from me and from those in close relationship with me. Therefore, I am ready for some relief, more relief, significant relief.

On one hand, I’ve spent a lifetime learning to manage and thrive with my ADHD. On the other, frequently when I encounter one of these Insta reels about ADHD, a new term pops up regarding an aspect of ADHD that is both so me and also so something I didn’t think of as part of that package. What do I do when I want to know more? What do I do when I sense there might be some understanding and actionable content somewhere? Buy a book, of course. In this case, related to the new/popular information. What exactly is executive dysfunction and dysregulation? Am I neurodivergent? Can I actually blame my sensitivity to criticism on ADHD? (Tongue in cheek, somewhat.) Is there something I can do to really deal with interrupting other people and/or persistent feelings of overwhelm?

Not all of these book possibilities are for adult women with ADHD, but the main list is. I have not read the vast majority of these (yet). I made this list by piecing together a number of online “best books” lists, as usual. Reading and reviewing comes next.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comFirst, I want to say that I am excited about Penn Holderness’s new book about ADHD, out on April 30, ADHD Is Awesome. I haven’t read it, but I really like the Holdernesses from following them online for years (which is kinda weird—I don’t usually do that sort of thing, but I just found I liked them and they live in Raleigh, so.) Penn has ADHD and has been open about it for years, and the book looks like it’ll be practical, funny, and positive.

There are some kid and teen books that I have used with my son over the years, and a few titles that were just recommended to us by a professional who did his teenage-level reevaluation. Here those are:

The ADHD Workbook for Kids, Lawrence E. Shapiro *The Survival Guide for Kids with Behavior Challenges,Thomas McIntyre (*) Journal of an ADHD Kid , Tobias and Joan Stumpf (*)The Sketchnote Handbook, Mike RohdeThriving with ADHD Workbook for Teens, Allison TylerStudy Strategies for Teens, Charlie HavenYes! You Will Understand Your Teen with ADHD, Jaycee DonovanLearning How to Learn, Oakley and SejnowskiAnd now for the list I really need, and perhaps you do, too. Forward-thinking books about ADHD as it presents in adult females (which can have everything to do with anything from hormones to cultural expectations). There are also many titles here that could be more general, either nongendered or for all ages:

Women with Attention Deficit Disorder, Sari SoldenThe Queen of Distraction, Terry MatlenThe Divergent Mind, Jenara NerenbergThe Disorganized Mind, Nancy A. RateyThe Mindfulness Prescription for Adult ADHD, Lidia ZylowskaHow to Keep House While Drowning, K. C. DavisADHD for Smart Ass Women, Tracy OtsukaThe Power of Different, Gail SaltzTaking Charge of Adult ADHD, Russel A. BarkleyADHD 2.0, Hallowell and RateyA Radical Guide for Women with ADHD, Solden and FrankOrganizing Solutions for People with ADHD, Susan C. PinskyUnderstanding ADHD in Girls and Women, Joanne SteerYou Mean I’m Not Lazy, Stupid, or Crazy?!, Kelly and RemundoBetter Late Than Never, Emma MahonyWho Am I?, Alain de BottonScattered Minds, Gabor MateWhy Has No One Told Me This Before?, Dr. Julie SmithTaking Charge of Adult ADHD, Barkley and BentonADHD According to Zoe, Zoe KesslerYour Brain’s Not Broken, Tamara RosierADHD Toolkit for Women, Sarah DavisThe Couple’s Guide to Thriving with ADHD, Orlov and KohlenbergerThe Smart but Scattered Guide to Success, Dawson and GuareHow to ADHD, Jessica McCabeOn Confidence, Alain de BottonADD-Friendly Ways to Organize Your Life, Kolberg and NadeuaThe ADHD Effect on Marriage, Mellissa Orlov100 Questions & Answers About ADHD in Women and Girls, Dr. Patricia QuinnThriving with Adult ADHD, Phil BoisierreThe Fog Lifted, Kristin SeymourOutside the Box, Thomas E. BrownHow to Be Everything, Emilie WapnickHelp for Women with ADHD, Joan WilderWhen an Adult You Love Has ADHD, Russell A. BarkleyDriven to Distraction, Edward M. HallowellThe Year I Met My Brain, Matilda BoseleyWhen Moms and Kids Have ADD, Quinn and NadeauADHD Workbook for Women, Tracy NeelThe Muse is In, Jill Bodonsky

More Attention, Less Deficit

, Ari Tuckman *

Women with Attention Deficit Disorder, Sari SoldenThe Queen of Distraction, Terry MatlenThe Divergent Mind, Jenara NerenbergThe Disorganized Mind, Nancy A. RateyThe Mindfulness Prescription for Adult ADHD, Lidia ZylowskaHow to Keep House While Drowning, K. C. DavisADHD for Smart Ass Women, Tracy OtsukaThe Power of Different, Gail SaltzTaking Charge of Adult ADHD, Russel A. BarkleyADHD 2.0, Hallowell and RateyA Radical Guide for Women with ADHD, Solden and FrankOrganizing Solutions for People with ADHD, Susan C. PinskyUnderstanding ADHD in Girls and Women, Joanne SteerYou Mean I’m Not Lazy, Stupid, or Crazy?!, Kelly and RemundoBetter Late Than Never, Emma MahonyWho Am I?, Alain de BottonScattered Minds, Gabor MateWhy Has No One Told Me This Before?, Dr. Julie SmithTaking Charge of Adult ADHD, Barkley and BentonADHD According to Zoe, Zoe KesslerYour Brain’s Not Broken, Tamara RosierADHD Toolkit for Women, Sarah DavisThe Couple’s Guide to Thriving with ADHD, Orlov and KohlenbergerThe Smart but Scattered Guide to Success, Dawson and GuareHow to ADHD, Jessica McCabeOn Confidence, Alain de BottonADD-Friendly Ways to Organize Your Life, Kolberg and NadeuaThe ADHD Effect on Marriage, Mellissa Orlov100 Questions & Answers About ADHD in Women and Girls, Dr. Patricia QuinnThriving with Adult ADHD, Phil BoisierreThe Fog Lifted, Kristin SeymourOutside the Box, Thomas E. BrownHow to Be Everything, Emilie WapnickHelp for Women with ADHD, Joan WilderWhen an Adult You Love Has ADHD, Russell A. BarkleyDriven to Distraction, Edward M. HallowellThe Year I Met My Brain, Matilda BoseleyWhen Moms and Kids Have ADD, Quinn and NadeauADHD Workbook for Women, Tracy NeelThe Muse is In, Jill Bodonsky

More Attention, Less Deficit

, Ari Tuckman *

April 16, 2024

Book Review: Wandering Stars

May I be so bold? It’s a no, thank you.

Here’s the rub: Native voices and Native perspectives are really important to me, have been for my entire life and I consider them to be woefully underrepresented. So, there is no way I am going to tell you not to read Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange when it is a Native-voiced novel getting so much attention. But I didn’t like it very much and I didn’t think it was very good. After having some (smaller) qualms with Orange’s first book, There There, and then waiting for him to improve before his second, I was let down. It was a step in the wrong direction. Which doesn’t mean he won’t write something amazing in the future, but I am not fond of continuing to give people the benefit of the doubt when I have yet to see their potential realized, even after two novels. And I’m tiring of other readers trusting the gatekeepers. Either it was a good book or it wasn’t, no matter who wrote it. This one, not in several ways.