Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 14

March 5, 2024

ARC Review: The Magic All Around

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comI wasn’t sure about this one by Jennifer Moorman because it’ didn’t really grab me. It wasn’t the characters, story, or setting, which were all cute right from the get-go, but the writing style. However, because I had an ARC in hand and wanted to give it a fair shot, I read on… until I was hooked and finished it up in like two days. The Magic All Around is a bit cozy (which many readers will appreciate, just not so much me most of the time), but it is also magic realism and romance, and will lure you in with quaintness and lovable characters.

Lillith has just died, leaving her young-twenties daughter, Mattie, adrift in a world that had been steered and dominated by her. Mattie heads to Ivy Ridge, Georgia, where she will go to the funeral and then take off for more of the adventurous, moorless life she had led with her mother. But Aunt Penelope and the rest of the family think she needs to stay in the mysterious, magical, family home, and Mattie is finally convinced when she finds out her inheritance is tied to a scavenger hunt that her mother left for her… because, you know, her mother knew exactly when she was going to die and what was going to happen, even what romantic strings left dangling that she could tug from the grave.

So, yes, I read this as an ARC. It took me a long time because I got swamped with book club reads very suddenly when I decided I needed to join six book clubs in the new year. (Technically, it had nothing to do with the new year so it does not count as a resolution.) When I didn’t get immediately whisked into the world of Magic All Around, I finished a bunch of book club reads I needed to have done ASAP. Then I realized I was being a butt by not prioritizing the ARCs I had taken and agreed to read, however informally. So I returned to reading Magic and, well, you already heard what happened.

I mean, the pitch for this one really called to me, in the first place. It is magical realism, I suppose, though it feels different from the usual magical realism. With the whole cozy thing, even the romance, it feels like a different genre. And, well, magical realism is sometimes limited, by definition, to literary fiction, which this one is not. The writing itself is more straight-forward, more story-telling a la Hallmark (which I’m not saying is a bad thing. People love these genres and devour them). With the whole small-town-heals-all-ills kinda thing. Whatever.

I don’t have that much to say here. I was not super into the writing style (which I keep saying, but more specifically, trite descriptions and choppy sentence flow as well as strange pacing choices), but Penelope immediately appealed to me. You can see the ending(s) coming from page one, which is again part of the cozy genre (because they you feel safe and warm and happy the whole way through, thus cozy). There is a certain amount of sparks that fly in the romance(s), though not as much as I would like. I’m also not sure that hearing Jonathan’s POV on top of Penelope’s and Mattie’s added to the story. (I also wasn’t always a fan of his, and their meet-cute was a little hard to sustain, believability-wise.) I would have had less of him and more Penelope, actually, but that’s not what we’re doing these days, is it? (Which is why, maybe, it would have been better: hear from the subplot POV more than the love interest POV.) Part of this might be because I am like Penelope’s age and certain aspects of her life are dreamy. I can relate to her and I want a magical house and magic hands, or whatever. Also, there is a whole lotta cheese. Some people love cheesiness in their books. I don’t. Nor do I like descriptions of cheesy art or of food or meals that don’t really make sense because they are so cheesy. There are some more serious themes here, but I didn’t feel emotionally invested enough to, like, cry over the book or anything. In the end, I just wanted to keep those pages turning to see these cute peeps in this cute town with their cute side-characters bring all the cute subplots and cute mysteries to a cute ending. And I was basically satisfied: the ending was the one I expected even though I was worried for like a chapter.

QUOTES:

“I was angry, and angry arguments are ugly and unfair, and I always regret what I say” (p163).

Literary Eats: The Seep

I had just read Little Thieves and was so happy to see all the German food. And then I picked up my next book club read, The Seep by Chana Porter, and found even more food! It is a very short book—probably a novella, actually—and the food tradition is set in a dystopian, sci-fi world, yet it is recognizable. I mean, this is supposed to be soon after our current time, I think, and so the foods have been adapted from what we already know, though they are vegetarian (kinda-sorta) and have some other nuances, like alcohol is considered old fashioned, etc.

Here is a choice between a simple meal, a more elaborate meal from My Attitude Is My Gratitude (even though I won’t be able to assess you before serving you) health café, a meal you might miss from the old times, and a dessert that Trina eats while she’s travelling and finding herself. Or maybe she’s just avoiding The Seep.

In a soup pot, heat 2 tablespoons neutral oil over medium heat. Add 1 chopped onion and cook until it begins to soften.Add 3 halved and sliced carrots, 2 diced turnips, 2 cloves minced garlic, 2 teaspoons dried dill, and 1/2 teaspoon black pepper and cook for 5 minutes.Add 1 chopped red bell pepper, 10 quartered prunes, and 1/2 cup raisins and cook until pepper softens.Add 1 small head of cabbage, rough-chopped and cook until it softens.Add 8 cups veggie broth, chicken broth or water, 1 large can of crushed tomatoes, and 1 teaspoon salt. Bring to a boil, reduce to a simmer, cover partially, and cook for half an hour.Add 1 tablespoons cider vinegar and 1 tablespoon honey. Taste for salt and seasonings.Serve with sour cream and fresh dill on a cold, overcast day.

In a soup pot, heat 2 tablespoons neutral oil over medium heat. Add 1 chopped onion and cook until it begins to soften.Add 3 halved and sliced carrots, 2 diced turnips, 2 cloves minced garlic, 2 teaspoons dried dill, and 1/2 teaspoon black pepper and cook for 5 minutes.Add 1 chopped red bell pepper, 10 quartered prunes, and 1/2 cup raisins and cook until pepper softens.Add 1 small head of cabbage, rough-chopped and cook until it softens.Add 8 cups veggie broth, chicken broth or water, 1 large can of crushed tomatoes, and 1 teaspoon salt. Bring to a boil, reduce to a simmer, cover partially, and cook for half an hour.Add 1 tablespoons cider vinegar and 1 tablespoon honey. Taste for salt and seasonings.Serve with sour cream and fresh dill on a cold, overcast day.

If you are going to use a charcoal grill, get that going. You’re going to need your heat source for the tofu in about 20 minutes.Remove 1 block extra firm tofu and press between paper towels with weights on top (like a cast iron Dutch oven). Set aside.Steam 1 cup sticky rice in a rice cooker, electric steamer, or bamboo steamer, per appliance’s instructions.Meanwhile, in a small Mason/Ball jar with a lid, combine 1 minced shallot, juice and zest of a lemon, 1/4 cup olive oil, and a generous pinch of salt. Close it up and give it a good shake. Set aside.In a serving bowl, toss 1/2 small head shredded Napa cabbage, 2 cups red leaf lettuce, 1 cup dandelion greens, 2 cups slivered spinach, 1 slivered endive, 1 small slivered radicchio and a good handful of chopped parsley. Set aside.In a small bowl, whisk together 1/2 cup tomato sauce, 1/4 cup rice vinegar, 1/4 cup soy sauce, 1/4 cup apple cider or juice, 1/4 cup tahini, 2 tablespoons brown sugar, 1 tablespoon gochujang, 2 cloves pressed garlic, 1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger, and 1 teaspoon salt. Set aside.Meanwhile, remove the tofu from its press and cut into approximately-1-inch cubes. Skewer onto metal skewers. You can make these on the grill or in a grill pan, or even broil them to get the barbecue flavor. I prefer the charcoal grill. Do what you need to do. Oil the surface of whatever you are going to grill on, but not in a way that starts a fire. The oil can go on the tofu. Grill the tofu, basting with the homemade barbecue sauce (step 6) throughout. You’re just looking to get some caramelization and charring. Remove, sprinkle with 1 teaspoon sesame seeds and 1 thin-sliced scallion and set aside.In a large pot or wok, heat 2 tablespoons peanut or neutral oil over medium-high heat. Add 3 rough-chopped scallions (white part only), 1 tablespoon sliced ginger and 2 sliced cloves garlic and saute until just browning. Add 4 rough-chopped dried chilies and 1 sliced, hot red chile. Saute for 1 minute or less.Stir in 4 cups fish broth. (I choose not to make fish broth at home because of the smell. Sorry. You can also go with a vegetable broth or even water.) Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for 10 minutes.Meanwhile, crack several black and white peppercorns on your cutting board. Heat ¼ cup oil (same as step 8) in a small pan. When hot, stir in the peppercorn and cook until fragrant and popping. Remove from heat.Meanwhile, thin-slice 4 tilapia filets on the bias. In a mixing bowl, toss the fish with ½ cup beer, ¼ cup cornstarch or rice flour, and a hefty pinch of salt. Set aside.After broth has simmered, add the oil with peppercorns and ¼ cup cider vinegar and taste for salt. Strain broth to remove all the bits.Return broth to the heat and bring to a simmer. Gently add in the fish, slowly. Cook just until cooked through. Remove fish to a separate plate, taking with you any new bits.Serve the salad tossed with the freshly-shaken dressing, tofu, rice, broth, and fish in individual, little bowls and plates.

If you are going to use a charcoal grill, get that going. You’re going to need your heat source for the tofu in about 20 minutes.Remove 1 block extra firm tofu and press between paper towels with weights on top (like a cast iron Dutch oven). Set aside.Steam 1 cup sticky rice in a rice cooker, electric steamer, or bamboo steamer, per appliance’s instructions.Meanwhile, in a small Mason/Ball jar with a lid, combine 1 minced shallot, juice and zest of a lemon, 1/4 cup olive oil, and a generous pinch of salt. Close it up and give it a good shake. Set aside.In a serving bowl, toss 1/2 small head shredded Napa cabbage, 2 cups red leaf lettuce, 1 cup dandelion greens, 2 cups slivered spinach, 1 slivered endive, 1 small slivered radicchio and a good handful of chopped parsley. Set aside.In a small bowl, whisk together 1/2 cup tomato sauce, 1/4 cup rice vinegar, 1/4 cup soy sauce, 1/4 cup apple cider or juice, 1/4 cup tahini, 2 tablespoons brown sugar, 1 tablespoon gochujang, 2 cloves pressed garlic, 1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger, and 1 teaspoon salt. Set aside.Meanwhile, remove the tofu from its press and cut into approximately-1-inch cubes. Skewer onto metal skewers. You can make these on the grill or in a grill pan, or even broil them to get the barbecue flavor. I prefer the charcoal grill. Do what you need to do. Oil the surface of whatever you are going to grill on, but not in a way that starts a fire. The oil can go on the tofu. Grill the tofu, basting with the homemade barbecue sauce (step 6) throughout. You’re just looking to get some caramelization and charring. Remove, sprinkle with 1 teaspoon sesame seeds and 1 thin-sliced scallion and set aside.In a large pot or wok, heat 2 tablespoons peanut or neutral oil over medium-high heat. Add 3 rough-chopped scallions (white part only), 1 tablespoon sliced ginger and 2 sliced cloves garlic and saute until just browning. Add 4 rough-chopped dried chilies and 1 sliced, hot red chile. Saute for 1 minute or less.Stir in 4 cups fish broth. (I choose not to make fish broth at home because of the smell. Sorry. You can also go with a vegetable broth or even water.) Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for 10 minutes.Meanwhile, crack several black and white peppercorns on your cutting board. Heat ¼ cup oil (same as step 8) in a small pan. When hot, stir in the peppercorn and cook until fragrant and popping. Remove from heat.Meanwhile, thin-slice 4 tilapia filets on the bias. In a mixing bowl, toss the fish with ½ cup beer, ¼ cup cornstarch or rice flour, and a hefty pinch of salt. Set aside.After broth has simmered, add the oil with peppercorns and ¼ cup cider vinegar and taste for salt. Strain broth to remove all the bits.Return broth to the heat and bring to a simmer. Gently add in the fish, slowly. Cook just until cooked through. Remove fish to a separate plate, taking with you any new bits.Serve the salad tossed with the freshly-shaken dressing, tofu, rice, broth, and fish in individual, little bowls and plates.

Preheat your oven to 400 degrees F. Oil a large loaf pan.In a mixing bowl, combine 1 pound ground beef, 1 pound ground pork, 1/2 cup ketchup, 1 diced small onion, 1/2 cup milk, 1/3 cup panko, 2 tablespoons rolled oats, 2 eggs, 1 tablespoon Dijon, 1 teaspoon salt, 1 teaspoon Italian seasoning, and 1/2 teaspoon pepper. Do not over-mix.Press mixture into the loaf pan. If it is very high in the pan, you will want to place a pan or foil underneath to catch errant juices and grease. Bake for 45 minutes, until the center is 165 degrees F (which could take an hour or more).Meanwhile, in a small pot, combine 1 cup ketchup, 1/3 cup brown sugar, 1/2 cup cream or 1/2 and 1/2, 1/4 cup cider vinegar, and 1 teaspoon Dijon. Heat over medium heat and simmer until sugar has dissolved. Set aside, rewarming at the end if needed.Spread 1/2 cup ketchup on the top of the loaf and broil until caramelizing and bubbling.Let meatloaf sit for 15 minutes. Turn out onto a platter and slice, then top it with the sauce.To be served with canned corn, saltines, and warm Coke.

Preheat your oven to 400 degrees F. Oil a large loaf pan.In a mixing bowl, combine 1 pound ground beef, 1 pound ground pork, 1/2 cup ketchup, 1 diced small onion, 1/2 cup milk, 1/3 cup panko, 2 tablespoons rolled oats, 2 eggs, 1 tablespoon Dijon, 1 teaspoon salt, 1 teaspoon Italian seasoning, and 1/2 teaspoon pepper. Do not over-mix.Press mixture into the loaf pan. If it is very high in the pan, you will want to place a pan or foil underneath to catch errant juices and grease. Bake for 45 minutes, until the center is 165 degrees F (which could take an hour or more).Meanwhile, in a small pot, combine 1 cup ketchup, 1/3 cup brown sugar, 1/2 cup cream or 1/2 and 1/2, 1/4 cup cider vinegar, and 1 teaspoon Dijon. Heat over medium heat and simmer until sugar has dissolved. Set aside, rewarming at the end if needed.Spread 1/2 cup ketchup on the top of the loaf and broil until caramelizing and bubbling.Let meatloaf sit for 15 minutes. Turn out onto a platter and slice, then top it with the sauce.To be served with canned corn, saltines, and warm Coke.

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Lightly oil a 9×13 inch baking pan.In a blender, whir 2 eggs, 2 egg whites, 1 cup milk, 1 tablespoon nut oil, 1 teaspoon sugar, and 1/4 teaspoon salt. Add 1 cup ap flour and blend just until smooth. Set aside to rest.In a small mixing bowl, combine 1 pound cottage cheese, 1/4 cup sugar, 3 tablespoons ap flour, and 1 teaspoon vanilla. Set aside.Heat a crepe pan or medium (preferably nonstick) skillet over medium heat. When hot, ladle in 1/4 cup of batter and spread quickly and evenly to coat bottom of the pan. When it is golden brown and comes up easily, flip it and cook until second side is golden brown. Remove to a plate and repeat with the remaining blintzes, noting that the first blintz is never a real winner and that you may have to adjust temperature and amount of batter to your tools and situation. Repeat until all batter is used.Fill blintzes with a couple tablespoons of the filling each so that you are distributing evenly. Roll them up like a burrito and line them into the oiled pan with their seams down. Bake for 15 minutes, until a little crispy.Meanwhile, in a small pot over medium heat, combine 1 package of frozen blueberries (or fresh) with 1/4 cup sugar, zest and juice of a lemon, and a pinch of salt. Allow to simmer until blueberries are breaking down. Taste for seasoning.Meanwhile, in a small bowl, whisk together 1 cup sour cream with 1/4 cup brown sugar. It will melt into the sour cream as it sits.Serve the hot sauce and a drizzle of the sour cream over the hot blintzes, with black coffee.

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Lightly oil a 9×13 inch baking pan.In a blender, whir 2 eggs, 2 egg whites, 1 cup milk, 1 tablespoon nut oil, 1 teaspoon sugar, and 1/4 teaspoon salt. Add 1 cup ap flour and blend just until smooth. Set aside to rest.In a small mixing bowl, combine 1 pound cottage cheese, 1/4 cup sugar, 3 tablespoons ap flour, and 1 teaspoon vanilla. Set aside.Heat a crepe pan or medium (preferably nonstick) skillet over medium heat. When hot, ladle in 1/4 cup of batter and spread quickly and evenly to coat bottom of the pan. When it is golden brown and comes up easily, flip it and cook until second side is golden brown. Remove to a plate and repeat with the remaining blintzes, noting that the first blintz is never a real winner and that you may have to adjust temperature and amount of batter to your tools and situation. Repeat until all batter is used.Fill blintzes with a couple tablespoons of the filling each so that you are distributing evenly. Roll them up like a burrito and line them into the oiled pan with their seams down. Bake for 15 minutes, until a little crispy.Meanwhile, in a small pot over medium heat, combine 1 package of frozen blueberries (or fresh) with 1/4 cup sugar, zest and juice of a lemon, and a pinch of salt. Allow to simmer until blueberries are breaking down. Taste for seasoning.Meanwhile, in a small bowl, whisk together 1 cup sour cream with 1/4 cup brown sugar. It will melt into the sour cream as it sits.Serve the hot sauce and a drizzle of the sour cream over the hot blintzes, with black coffee.

March 4, 2024

Read Me: Excerpt from White Noise

I have just started reading Don Delillo’s White Noise for a literary classics book club. On chapter six, at page 22, I came across this scene. I knew it would never make it whole into my quotes from the book, but I also knew that–despite this book maybe not being what I am totally into–this is perfect writing in a number of ways. It’s witty, smart, obviously, but it’s also great dialogue, great character development, and deepens the setting, as well. And perhaps I can relate to trying to talk to a teenager.

“It’s going to rain tonight.”

“It’s raining now,” I said.

“The radio said tonight.”

I drove him to school on his first day back after a sore throat and fever. A woman in a yellow slicker held up traffic to let some children cross. I pictured her in a soup commercial taking off her oilskin hat as she entered the kitchen where her husband stood over the pot of smoky lobster bisque, a smallish man with six weeks to live.

“Look at the windshield,” I said. “Is that rain or isn’t it?”

“I’m only telling you what they said.”

“Just because it’s on the radio doesn’t mean we have to suspend belief in the evidence of our senses.”

“Our senses? Our senses are wrong a lot more often than they’re right. This has been proved in the laboratory. Don’t you know about all those theorems that say nothing is what it seems? There’s no past, present, or future outside our own mind. They so-called laws of motion are a big hoax. Even sound can trick the mind. Just because you don’t hear a sound doesn’t mean it’s not out there. Dogs can hear it. Other animals. And I’m sure there are sounds even dogs can’t hear. But they exist in the air, in waves. Maybe they never stop. High, high, high-pitched. Coming from somewhere.”

“Is it raining,” I said, “or isn’t it?”

“I wouldn’t want to have to say.”

“What if someone held a gun to your head?”

“Who, you?”

“Someone. A man in a trenchcoat and smoky glasses. He holds a gun to your head and says, ‘Is it raining or isn’t it? All you have to do is tell the truth and I’ll put away my gun and take the next flight out of here.'”

“What truth does he want? Does he want the truth of someone traveling at almost the speed of light in another galaxy? Does he want the truth of someone in orbit around a neutron star? Maybe if these people could see us through a telescope we might look like we were two feet two inches tall and it might be raining yesterday instead of today.”

“He’s holding a gun to your head. He was your truth.”

“What good is my truth? My truth means nothing. What if this guy with the gun comes from a planet in a whole different solar system? What we call rain he calls soap. What we call apples he calls rain. So what am I supposed to tell him?”

“His name is Frank J. Smalley and he comes from St. Louis.”

“He wants to know if it’s raining now, at this very minute?”

“Here and now. That’s right.”

“Is there such a thing as now? /Now’ comes and goes as soon as you say it. How can I say it’s raining now if your so-called ‘now’ becomes ‘then’ as soon as I say it?”

“You said there was no past, present, or future.”

“Only in our verbs. That’s the only place we find it.”

“Rain is a noun. Is there rain here, in this precise locality, at whatever time within the next two minutes that you choose to respond to the question?”

“If you want to talk about this precise locality while you’re in a vehicle that’s obviously moving, then I think that’s the trouble with this discussion.”

“Just give me an answer, okay, Heinrich?”

“The best I could do is make a guess.”

“Either it’s raining or it isn’t,” I said.

“Exactly. That’s my whole point. You’d be guessing. Six of one, half dozen of the other.”

“But you see it’s raining.”

“You see the sun moving across the sky. But is the sun moving across the sky or is the earth turning?”

“I don’t accept the analogy.”

“You’re so sure that’s rain. How do you know it’s not sulfuric acid from factories across the river? How do you know it’s not fallout from a war in China? You want an answer here and now. Can you prove, here and how, that this stuff is rain? How to I know that what you call rain is really rain? What is rain anyway?”

“It’s the stuff that falls from the sky and gets you what is called wet.”

“I’m not wet. Are you wet?”

“All right,” I said. “Very good.”

“No, seriously, are you wet?”

“First-rate,” I told him. “A victory of uncertainty, randomness and chaos. Science’s finest hour.”

“Be sarcastic.”

“The sophists and the hairsplitters enjoy their finest hour.”

“Go ahead, be sarcastic, I don’t care.”

from White Noise by Don Delillo, pp.22-24

March 2, 2024

What to Read in March

It is the month for St. Patty’s Day and it is the month for the Oscars. It’s also just another month, the third month of 2024, and a time when we’ll still be book-clubbing and TBR reading and noticing a few of the new books.

As for Irish literature in honor of St. Patty’s Day (notice my last name is Flaherty and that my Flaherty father-in-law’s birthday is on St. Patty’s Day), I’m going to make a few recommendations considering not just that the books were written by Irish authors, but also that featured Ireland significantly (even, in one case, as an alternate, dystopic Ireland). Actually, though Irish literature had been prolific, important, and popular for centuries (though it wasn’t called Ireland originally), Irish literature is having yet another renaissance, lately, taking home the Booker Prize and many best-ofs last year, my book clubs have been so riddled with Irish titles that people are starting to ask they they pick anything besides Irish lit, needing a little variety. The Irish just have a way with words.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch is my favorite title so far this year. It is a little artsy: stream of consciousness and sans punctuation, which is appropriately Irish in style and tradition for a St. Patty’s read. Also, it’s bleak. (Still, so Irish.) But it’s also just an amazing book and I was entranced by both the writing and the depth of the story.

I read Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt for the second time in 2020. I actually wasn’t as impressed with it as I remembered being the first time around, but it certainly is interesting, full of eye-opening moments. And it’s a classic of Irish literature, by now. And it won the Pulitzer in 1996. The memoir begins with Irish immigrants in New York and then follows them back to Limerick Ireland, all during McCourt’s tumultuous childhood. There is also a movie to watch after you read it.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy was not really my favorite read of the year to date, but it is very Irish and worth the read, I think. I am about to review it for you (just give me a few days, as I am behind four books). Again, lacking traditional punctuation, mostly quotation marks, and fairly bleak. This affair-centered book is about the Troubles and mostly deals with interaction between the Protestants and Catholics, which is, yes, super interesting, especially for those who like historical fiction (but also literary fiction).

As for St. Patty’s Day reads, I looked at some of the most famous (across various genres) Irish authors and then for one of their books that featured Ireland and was one of their top books. You’ll have to tell me how I did, but here are the options I came up with:

Maeve Binchy, Circle of FriendsSally Rooney, Normal PeopleMaggie O’Farrell, This Must Be the Place (which seems to be her one book that takes place, at least some, in Ireland. I loved Hamleth (takes place in England) and am really looking forward to The Marriage Portrait (Italy), but at this point I would probably follow her anywhere.James Joyce, Ulysses or

The Dubliners

Tana French, In the Woods (which is the first book in the Dublin Murder Squad series, though not her highest ranked. I always like to start at the beginning, though. She also has a new book out this month,

The Hunter

.)Colum McCann, Everything in This Country Must (Again, not is most lauded (which would be Let the Great World Spin), but about the Troubles. (I swear, even if you’re from a different country, everyone writes about London and/or New York!) He also has a nonfiction, writing book that I would like to read,

Letters to a Young Writer.

)Roddy Doyle, The Commitments (The Barrytown Trilogy #1)

Maeve Binchy, Circle of FriendsSally Rooney, Normal PeopleMaggie O’Farrell, This Must Be the Place (which seems to be her one book that takes place, at least some, in Ireland. I loved Hamleth (takes place in England) and am really looking forward to The Marriage Portrait (Italy), but at this point I would probably follow her anywhere.James Joyce, Ulysses or

The Dubliners

Tana French, In the Woods (which is the first book in the Dublin Murder Squad series, though not her highest ranked. I always like to start at the beginning, though. She also has a new book out this month,

The Hunter

.)Colum McCann, Everything in This Country Must (Again, not is most lauded (which would be Let the Great World Spin), but about the Troubles. (I swear, even if you’re from a different country, everyone writes about London and/or New York!) He also has a nonfiction, writing book that I would like to read,

Letters to a Young Writer.

)Roddy Doyle, The Commitments (The Barrytown Trilogy #1)And here are some of the not, new books, highly anticipated March releases:

A debut novel, How to Solve Your Own Murder by Kristin Perrin is being called “an enormously fun mystery” (GoodReads). The review I heard of it on a podcast (could it have been The New York Times Book Review?) had be convinced this would be a great one to read.

If there’s one book that I have heard on more lists of what to read in 2024, it is the memoir, House of Hidden Meanings by RuPaul. As with many biographies, the author may not be someone you usually pay attention to, but little birdies keep saying this is a well-written and poignant not-to-miss.

We’ll get to some Oscars reads in a second, but I’m going to throw James by Percival Everett out there as a highly anticipated book. He is the author of a book I’m going to recommend for Oscars reading, but he also has a novel coming out this month (publicity, anyone?). Just like any other hyped book, it’s supposed to be good. And it’s a retelling of Huck Finn, from Jim’s (the slave’s) POV.

The Great Divide by Christina Henriquez is a novel about the building of the Panama Canal in the tradition of Latin American literature like Isabel Allende (so I’ve heard). I would also be curious to check out her debut novel, which won about 1,000 awards and is about the American immigrant experience, The Book of Unknown Americans.

And here we are at the other Percival Everett recommendation, which I am making as an Oscars season recommendation. I did see a lot of movies this part year, at the theater, but somehow missed a number of the ones that are nominated. However, American Fiction was one of my favorites of the year, and I am totally pulling for it. It is based on the early-2000s novel by Percival Everett, Erasure, which I am curious to read mostly because I appreciated the movie so much. I am also really interested in reading the graphic novel, Nimona (N. D. Stevenson), which quite frankly looks amazing (and I really liked the movie). The other two books that Oscar-nom movies were based on and that look to be worth the read are Killers of the Flower Moon (David Grann) and The Color Purple (Alice Walker), the first of which is nonfiction with great ratings and a super-interesting topic, and the second of which is a classic.

I have less book club reads this month because two of the clubs had to move their meetings and double-up in April. So in April, I’ll have more than normal. At any rate, here are the books I’ll be reading for book clubs in March:

White Noise

, Don Delillo (literary book club)

Firekeeper’s Daughter

, Angelline Bouley (YA for adults book club)

The Astronomer

, Brian Biswas (Okay, so this is not even a book club I usually got to, but after seeing Biswas read over the summer of 2023 and buying the book, I think I’m gonna’ tag along with this group for one meeting.)

Stay with Me

, Ayobami Adebayo (contemporary books book club)

The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

, H. G. Parry (which is for a speculative fiction book club, but I would like to precede it with a reading of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield and follow it with Barbara Kingsolver’s super hot

Demon Copperhead

.)

White Noise

, Don Delillo (literary book club)

Firekeeper’s Daughter

, Angelline Bouley (YA for adults book club)

The Astronomer

, Brian Biswas (Okay, so this is not even a book club I usually got to, but after seeing Biswas read over the summer of 2023 and buying the book, I think I’m gonna’ tag along with this group for one meeting.)

Stay with Me

, Ayobami Adebayo (contemporary books book club)

The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep

, H. G. Parry (which is for a speculative fiction book club, but I would like to precede it with a reading of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield and follow it with Barbara Kingsolver’s super hot

Demon Copperhead

.)

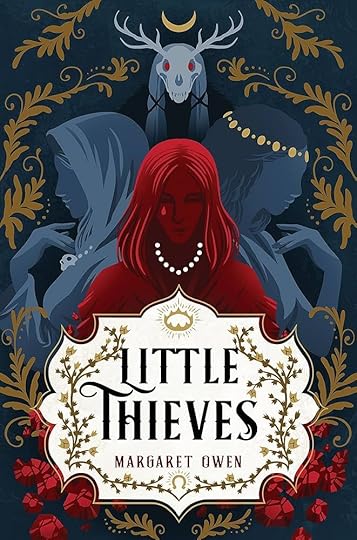

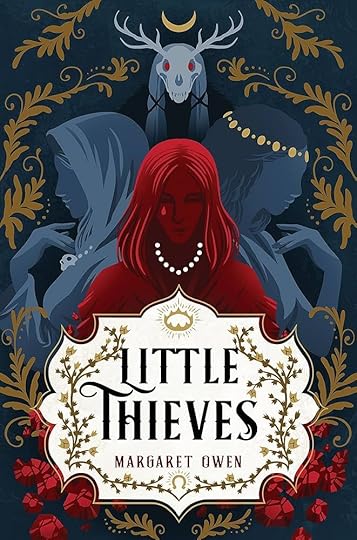

Little Thieves by Margaret Owen. This is fantasy/fairy tale for YA, so no, it’s not going to be for everyone. It is also lighter reading, as much genre reading is. For what it was, I found it fun to read and I am going to eventually read the second and third books in the trilogy, though it would possible top stop at the end of this one and be fine.

The Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende. A lot of us know that Allende can write, right? And despite having a thing for Latin American literature and magic realism (which this one is actually not), I had only preciously read The Stories of Eva Luna, years and years ago. So I was happy to get around to another one. This novel is beautifully written and neck-deep in interesting history. It has hard to deal with topics and sometimes a loopy plotline, but it is amazing.

The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai. Okay, so I’m not even done reading this one yet, but it is very safe for me to put it here as a favorite read of the month: I’m almost done and I know how I feel about it. I was reading it in preparation for a Rebecca Makkai event for the paperback version of her newest novel, I Have Some Questions for You. I mean, ya’ll, The Great Believers is incredible. It just is. A handful of people don’t agree with me or talk about voyeurism (about the Boystown gay community in Chicago during the AIDs Crisis of the 1980s), but I felt drawn in, happy with the writing, and sympathetic to the characters as well as informed historically.

I mean, it’s the month of the 2024 Oscars, so of course I have some movie recommendations (though it’s pretty late in the game to try to watch them before the 10th). Here are a number of the nominees, the ones I am interested in and/or think you might be able to actually find somewhere, as well as some of my favorite movies of the years which did not get a nomination, either unfairly or because they’re not the right type of movie for that sort of thing.

Your first move is to watch American Fiction, which I should be reviewing this weekend with a couple other movies. As I already said, I loved this movie and am thrilled it’s been nominated.

The Holdovers (haven’t seen, just missed it, without a Peacock subscription, you can pay $6 to watch it elsewhere) Oppenheimer (haven’t seen, just missed it, without a Peacock subscription, you can pay $6 to watch it elsewhere) Barbie (saw it, enjoyed it, not sure it struck me as an Oscar kind of movie, though I kinda get why we’re going there, you can watch it with Max, Hulu, YouTube or Amazon prime memberships) Poor Things (saw it, had mixed feelings about it after really looking forward to it, you can watch it for like $20 on some streaming services, or find it at some movie theaters still) Killers of the Flower Moon (haven’t seen it, just missed it, without Apple TV you’re going to pay $20 to watch it) The Color Purple (haven’t seen it, got outvoted, you can watch it with Max, Hulu, YouTube or Amazon prime memberships) Anatomy of a Fall (haven’t seen it, was concerned about triggers, you can pay $6 to watch it on Apple TV or Amazon) The Zone of Interest (haven’t seen it, totally missed it, you’re going to pay $20 to stream it) Maestro (haven’t seen it, really really missed it, you can catch it on Netflix) Past Lives (saw it, really liked it (I think, it’s been awhile),you can watch it on like eight different, premium, streaming memberships)My personal faves of the year (besides American Fiction, Barbie, and Past Lives):

Nimona

Across the Spider-Verse

Argylle

Lisa Frankenstein

Are You There God?… It’s Me, Margaret

You Hurt My Feelings

Dream Scenario

Turtle Mutant Mayhem

She Came to Me

Nimona

Across the Spider-Verse

Argylle

Lisa Frankenstein

Are You There God?… It’s Me, Margaret

You Hurt My Feelings

Dream Scenario

Turtle Mutant Mayhem

She Came to Me

And a shoutout to The Marvels and Dungeons and Dragons: Honor Among Thieves and Wonka and Wish and Anyone but You and even The Little Mermaid for a good time, even if it’s not an Oscar-worthy kind of thing. That’s not what all entertainment aims to be, so…

February 22, 2024

Quotable: Isabel Allende

“Yeah, I am the least athletic person in the universe, but I compare writing to training for a sport. You have to do it every single day and nobody cares about your effort or how much time you spent or how much was wasted time. It doesn’t matter. It’s the end of the performance that is the only thing that really counts. And I think, in writing, it’s the same.” -Isabel Allende, in the interview with Madeline Miller at the back of A Long Petal of the Sea

February 16, 2024

Book Review: The Seep

A truly strange book, The Seep by Chana Porter is extremely short (for long-form) science fiction. In fact, it’s really a novella and has small pages, large margins, and space between the lines. And really, I suppose, the book itself isn’t that strange, but the feeling while reading it is of being among strangeness. It is full of intriguing ideas and world-building, and puts the reader in a dystopian, not-too-far-off future that will lead them into thinking about things now. And it is also the fairly depressing tale of an alcoholic mourning the loss of their wife. I’m having a hard time determining whether I “liked” it or not, but I think many people would like to read it. And with such a small time-investment, why not?

It is the near-future and the alien invasion we were all waiting for has come, but there is nothing about it that we had expected. The Seep came silently and peacefully and invaded our minds, bodies, and culture in a curious, helpful, and yet creepily passive-aggressive way, bettering the society of the world so that people eat, drink, and are merry all the time, freeing themselves to dream the impossible and live forever. Trina remembers the old days, before The Seep, and can’t help being old-fashioned. When her wife, Deeba, dreams of reincarnating as a baby, Trina is left alone, resentful, confused and depressed, which The Seep (and her neighbors) don’t approve of.

I read this book because it was the second book in the speculative fiction book club that I joined (at least temporarily). The last book was fantasy, so maybe they jump back and forth? Sci fi is less of my jam than fantasy, but I have read a fair amount of it (my favorites being anything Ray Bradbury, The Giver, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and, if you count it as such, The Hunger Games trilogy, though there are others that I also liked). This book is more along the vein of what I have been seeing in science fiction short stories lately, like the stories that I will blog about soon, “Rabbit Test” (Samantha Mills) and “To Carry You Inside You” (Tia Tashiro). I can’t say I love this style, as it always sorta creeps me out and leaves me, um, empty-feeling, but it is also intriguing and often thought-provoking.

The Seep is hard-core sci-fi, but it is also a mash-up of a fable and an odyssey (or quest). It makes me think as much about Gibran Khalil’s The Prophet or Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince with its trippy allegory and journey-of-discovery-which-is-also-an-actual-geographical-journey, than any science fiction I have read (or seen), including alien invasion or creepy-crawly, hedonistic utopias. Though all of that is there. As for a fable, it is the right length. As for a quest (or odyssey), it is quite short, which left the plot and characters as vehicles more than participants in a dramatic story. Both of these things tend toward the random, but Porter leans heavily on Trina’s humanity, writing from inside her head, and we do dive pretty deep for such a short read. And yet, it felt cold and calculated, in the long run. I was far from emotionally invested, even though alcoholism and loss are things that have touched my own life. I was paying much more attention to how The Seep worked and how people had reacted to it than to Trina herself. We never really get to what this book might be considering.

Speaking of Trina, she is supposedly a trans woman, Native American, and 50. Um. I wasn’t even sure about any of these things except that they were in the write-ups and on the book jacket. Not only do the first two of these things not really play out, they are not important to the story. We have other characters and situations that are more contemplative about gender, and ethnicity seems not to matter at all. I am at a loss for why these two things were included, except as a chance for representation? If that’s the case, I would have liked to even notice either of these things, let alone feel like they belonged and contributed to the character and her story. (There is one instance in which the transgender-ness helps with the plot and understanding a relationship, but it was a little confusing, just a few hints, and could have been missed altogether.) There is something in this book about identity, but I can’t quite put my finger on it amidst all the lists, too-direct writing, and lack of (plot and character) development.

This is one of those modern stories that leaves you to picture these people however you want to… until all of a sudden it says “long hair” near the end and you’re like, nu-uh, she’s been in a pixie cut the whole time, thanks to my imagination and your lack of description. (Porter does give us some description of some of the characters, just not Trina so much.) I know lots of readers take issue with the stop-the-action and give a straight-forward description thing. But I don’t think filling us in on some pertinent details so that we can picture a person or place is a bad thing (and, more importantly, don’t get contradicted much later). I think it’s a great thing, actually, and can be done creatively. Occasionally, you come across a story where what the characters look like or where they are don’t matter so much, but I still think readers should be given enough information to place themselves in a scene and look at the characters you are having them meet. Plain and simple. And when you throw in a physical detail late in the book, well I’m just annoyed. It’s not just you, Porter. Not at all. (I was forced, during my recent reading of Biography of X to eventually assign the characters actors—Sigourney Weaver and Rosie Perez, actually—just so I could keep seeing the events in my head; their amorphousness led them to shift constantly in my reading, which was—and is—as distracting as a lame paragraph of description.)

There is also something about Porter’s writing that feels a little new, a little student, to me. I think her ideas are great, but something about her voice made me feel like she was not an authority, that she was not the one to tell me this story. The writing is sparse, yes, but in a way that seems accidental. You have all these short sentences and simple phrases, and then you have a paragraph giving us the components of all three meals served to Trina and some strangers at a café. (I love food, so I was happy with this, but not with the writing tone.) I guess what I’m saying is that this book read to me like Porter is still finding her voice; her concepts were much stronger than her execution. Again, wouldn’t be the first time.

That’s it for me. The Seep is one of those books I totally might recommend to someone (like my husband, which I did), especially since it is so short. But I also can’t honestly say I liked it as a work of literature. And the cover weirds me out; it’s just not balanced right. It was a pretty good experience, but not exactly because of the writing. It was like a rough draft that needed a whole lot more fleshing out and consideration of themes, etc. Then again, it was easy to read. So read away and I’ll just sit here wishing Goodreads had a half-star option.

After all that I just said, The Seep is Chana Porter’s first novel. So, she was sorta just starting out (in 2020) with that one, except that it won some awards (or almost-awards) and she is a MacDowell fellow who has taught at several places. She also started a STEM/spec-fic writing summer program for girls and non-binary kids. And she is a playwright. And now that I say that, I wonder if I wouldn’t see the writing style differently if I knew that she writes more plays than novels.

“…The Future, that shimmering, mercurial beast, constantly breaking our hearts” (p2).

“I don’t know if this is the end of life as we know it, or the beginning of a grand adventure, or perhaps both. All I have is my uncertainty. And really, that’s all I’ve ever had” (p9).

“After years of struggle in the old scarcity paradigm, Trina finally had freedom to think about what she wanted to do with her copious time” (p13).

“Talking was easy. Communication was hard” (p108).

“If she shot Horizon Line, the person she’d really be killing was herself, her old self. She’d no longer be Trina, the person who would never fire a gun at someone” (p108).

“You people, you think happiness is the only important thing about being alive. I’m serious when I say I’m not interested in happiness. This old body hurts. That’s as worthy an experience as any” (p109).

February 15, 2024

Book Review with a Bonus: Little Thieves and The Goose Girl

I really enjoyed Little Thieves by Margaret Owen. I enjoyed it so much that I didn’t even notice it was first person, present tense until I was practically done reading it, which is a testament to when that very thing works for YA. First-person is the most popular POV these days for YA and present tense seems to be on the rise, but I don’t think it should be used as much as it is. In Little Thieves, technically the fairy tales (seven in all, each a few pages long) are in past tense, but the rest of it is a draw-close and tell-all from the POV of a spunky, feisty, perhaps misbehaving sixteen-year-old girl, so it pretty much works here. It’s no literary giant (and it’s not even a Six of Crows), but it’s great fun. Funny. Kinda light considering the subject matter and the evil therein. The pieces come together in the end, and the ending is better than just satisfying: it’s surprising and satisfying.

Note: Owen includes a content warning at the beginning of the book, which includes abuse and sexual abuse. Neither are quite explicit.

Vanja was taken to the woods when she was a toddler, to get rid of her: a thirteenth child of a thirteenth child. The Low Gods, Death and Fortune, fostered her and raise her. But when it becomes a matter of a lifetime of servitude and the reality of rejection, Vanja ends up on a journey from the castle where she is a maidservant, to a girl betrothed to a neighboring prince… and somehow becomes both a fake princess and a jewel thief on top of it all, in a wild grab to earn her freedom. But taking what is not yours is going to bring ill luck to your door, either as the curse of a forest goddess, the schemes of power-hungry royalty, the eye of the fairy-tale law, or the hurt feelings of your abandoned friends… or all four. Vanja must figure out how to break the curse and get out of town before everything (and Death) catches up with her.

This is the first book that I read for a YA-for-adults book club I was trying out. I mean, I already read a lot of YA (partly because I write YA), so I thought it would be fun to find some other grown-ups who do the same (besides my friend two states away). I don’t think this book had crossed my radar, before, which seems strange to me now that I have read it. The thing is, there are just so many books out there. This is YA/fairy-tale/fantasy. It has a great heroine and a good romance (though that is in the background to the adventure and the soul-searching/coming-of-age).

Little Thieves is the first in a trilogy which consists of Little Thieves, Painted Devils, and the 2025-anticipated Holy Terrors. It is a retelling of “The Goose Girl,” a Brothers Grimm fairy tale (and also a book in the Books of Bayern tetralogy by Shannon Hale). It could be read alone, but I liked the world, story, and characters enough that I plan to read the rest of the trilogy—the second one soon and the third one, well, at least next year.

I will admit that during the first couple chapters, I wondered if I would like this book. The writing proficiency is fine, but left me underwhelmed. And it takes time to get to know the other things, so I wasn’t sure where I would fall. But in the end, the writing style is at least endearing, even if it doesn’t have literary acrobatics (or even cleanness or complete clearness) going for it. The voice of the main character is strong and we get a ton of sass and spice, even as the narrator addresses us directly in snarky asides and wanders into emotional epiphanies. There are some LGBTQ+ characters (who, for the record, felt shoe-horned in). Overall, though, the writing borders on chaste, so don’t expect any steamy scenes, though the romance(s) do have energy and some sizzle. There’s more innuendo than explicitness.

There are occasional plot holes and inconsistencies, though probably not any huge ones; more like intra-scene issues. You can relax and get past that. But you will also have to accept that this story is in no way consistent with medieval times or German fairy tales. What I mean is that some of the culture is there (like food and clothes and weather and whatever), but the ideas are almost completely modern. I am aware that this is the way some authors have chosen to deal with writing “historical” when many of their ideals don’t jive with the times and they want to be PC or whatever. I don’t think this is a fault, necessarily (unless it is a fault of many writers), but don’t expect historical accuracy, especially when it comes to ideas. A character might be stuck in an arranged marriage, but they’re not going to think or behave like someone who is from a time period where arranged marriages were the norm, for example. Vanja is a modern, girl-power heroine, after all. Which also means she’s not all good. You know, the whole thief thing. Etc.

I don’t have much more to say about this book except that I ended up really enjoying it and looking forward to the next book in the series, wondering what happens with miss sassy-pants and her love interest and maybe even some of the other characters. Definitely some funny scenes. Tension around every corner. Plot twists all over the place. Adequate writing. A complete world consisting of Germany, fairy tales, the medieval world, and folk magic.

Margaret Owen is a newer writer with a fun bio HERE, at her website. She has been pumping out a book a year in her (first?) two YA series, Little Thieves and The Merciful Crow (a duology of The Merciful Crow and The Faithless Hawk). The Merciful Crow series is called “gritty YA.” While the ratings on the first book aren’t amazing, it was fairly popular, and the ratings on the second book are more consistent with the Little Thieves books… like a 4.3. As I said earlier, Little Thieves will be a trilogy. Owen does her own, impressive artwork, and has some other, universe-related shorts and things around and about.

“The answer to a question like this is always, always no, by the way. It’s a trick. You might tell them something they already knew; you might confess to a greater trespass than they imagined. If they’re going to catch you, make them work for it” (p160).

“Some part of me has always looked for how I brought these things on myself …. and if I could figure out where I went wrong, they wouldn’t call me stupid or throw things or strike me. / There had to be a reason for it. That made it something I could control. Something I could hope to stop. / It’s the worst kind of relief for someone to say it was never in my control” (p344).

“…I’m learning the bitter difference between independence and self-exile” (p346).

“For all my schemes and facades and artifice, I am not prepared in the slightest for the simple, devastating intimacy of being believed” (p355).

“Klemens had a theory that most crimes derive from five motives: greed, love, hate, revenge, or fear” (p391).

THE GOOSE GIRL

I grabbed my copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales off of the shelf to read “The Goose Girl.” In case you didn’t know, the Brothers Grimm—Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm—were story collectors, not story-makers like the usual, modern writer. They travelled around collecting oral stories and then used different means to translate them to the page. “The Goose Girl” is one of these stories, collected from an old, oral tradition in what would become Germany.

“The Goose Girl” is a pretty standard fairy tale. It is a little dark, but not excessively violent (well, maybe it is, actually), and includes some sort of moral amidst its frank randomness. In it, a princess is betrothed to a prince in another kingdom, and travels there to be married, with her chambermaid. Also, they take the princess’s talking horse. On the journey, the maid tricks or traps the princess into becoming the maid while the maid poses as the princess. Then the new princess abandons the real princess and goes off to live the other’s life. There are a lot of moments where the real princess calls on help or at least advice from inanimate objects and they answer in bad poetry. There is a talking skull. A slasher-movie level punishment. And there is a poor goose boy who reveals that the princess hasn’t really learned anything even though she’ll get what she “deserves”—a kingdom—in the end. As usual, there are some strange senses of rightness that translate as foreign to us: like keeping an oath to someone who has wrongfully acquired it. And characters who accept their fate and wait for the great balancing scales of karma and magic to fix it.

I can see why an author would read this story and wonder about it, want to tell it as an actually nuanced story with realistic characters. While Owen disposes of some large plot points from “The Goose Girl”—like the goose boy and his hat that keeps being sung over the mountain while the princess washes her hair (while she’s supposed to be working, I might add)—she transposes other things—like the horse’s skull and the importance of Falada to the climax—in really great ways. It makes perfect sense that Owen would shift perspectives to the maid, too. Not only is this right up our current culture’s alley, but “The Goose Girl”’s princess doesn’t exactly inspire a whole lotta sympathy (though Shannon Hale would make an attempt at earning her some in the Books of Bayern’s series, The Goose Girl). Still, taking something as small as a fairy tale and expanding it as well as reimagining it the way that Owen did: it’s pretty special.

I can’t say I love “The Goose Girl” as a story. It’s weird and gory and you can’t quite like the heroine, who is much more a victim than a heroine (which is, again, why Owen was likely drawn to it). I do like Grimms Fairy Tales as a whole, though, and my kids—when they were kids—liked it even more than me. For that review, follow the link.

Just a few days ago, it was announced that Little Thieves would be made into an animated movie (by someone previously from Disney and Netflix). I don’t know how much to believe this news, as I can’t find it at any mainstream publications, but it’s also not the kind of thing that would get much press… yet. I guess I am hoping that this is true. Animated could be a great way to go with so much magic (not to mention characters in the skin of other characters), but it does make me wonder about what age audience they will be shooting for. And quite frankly, you can’t know how great a movie will be, or even if it will be finished, until it’s made.

The book trailer can be found HERE.

February 14, 2024

Literary Eats: Little Thieves

You already know that I am obsessed with books. You might not already know that I am obsessed with food. Before this blog, I had two different food blogs, and only stopped maintaining them because I couldn’t keep all those plates spinning along with everything else. But I kept cooking and baking. It goes without saying, then, that I have a little radar that beeps at me (in my head) whenever I come across especially foodie books or scenes. I was thrilled, then, when I was reading Margaret Owen’s Little Thieves and I stumbled upon more than one foodie scene based on German cuisine (which is because the book is based on a German fairy tale). My family has some German roots and meal traditions, and I am very fond of German food.

If you, too, are reading Little Thieves (or the sequel, Painted Devils, or, after April 2025, the final book in the series, Holy Terrors), I have made some recipes for you inspired by these scenes in the book. You could make the whole thing for dinner, just because, or you could host a book club dinner. Or you could just bring one dish to your book club. You could also have absolutely no reason besides it sounds delicious. And then read the book.

Dice 5 slices of bread and add to the bottom of a medium-large mixing bowl. Drizzle over 1 1/3 cup warm milk (or cream). Let sit.Meanwhile, rough-cut 1 pound beef liver and place into a food processor with 1 chopped onion. Process until nearly smooth.Add liver to the bread cubes, then add 1 tablespoon minced parsley, 4 slices of small-diced bacon, ½ teaspoon marjoram, 1/3 cup breadcrumbs, 2 eggs, 1 teaspoon salt, and a generous pinch of pepper. Stir until combined.Meanwhile, bring 8 cups beef broth to a boil. Reduce to a rolling simmer. Form heaping serving-spoonfuls of liver mixture into quenelles and add to the broth one at a time. Simmer for 25 minutes and check for doneness. Serve garnished with more parsley and with sauerkraut.

Dice 5 slices of bread and add to the bottom of a medium-large mixing bowl. Drizzle over 1 1/3 cup warm milk (or cream). Let sit.Meanwhile, rough-cut 1 pound beef liver and place into a food processor with 1 chopped onion. Process until nearly smooth.Add liver to the bread cubes, then add 1 tablespoon minced parsley, 4 slices of small-diced bacon, ½ teaspoon marjoram, 1/3 cup breadcrumbs, 2 eggs, 1 teaspoon salt, and a generous pinch of pepper. Stir until combined.Meanwhile, bring 8 cups beef broth to a boil. Reduce to a rolling simmer. Form heaping serving-spoonfuls of liver mixture into quenelles and add to the broth one at a time. Simmer for 25 minutes and check for doneness. Serve garnished with more parsley and with sauerkraut.

(Schnitzel isn’t mentioned in the book. You could buy a German-style sausage instead, especially weisswurst (though a bratwurst would be easier to find) and grill that up. The benefit of the weisswurst is that it may freak out your Vanjas, but a brat will be effective for any innuendos you need help with. Or just go for the schnitzel because it is so delicious. For a feast, it’s both.)

Preheat your oven to 160F.Prepare your breading station. Set out 3 blates. (You read that right. Look it up.) In the first, mix together ¾ cup all purpose flour, 1 teaspoon salt, ½ teaspoon paprika, and ½ teaspoon black pepper. In the second blate, whisk together 2 eggs with 2 tablespoons milk. In the third, spread out 1 ½ cups breadcrumbs.Prepare another countertop by layering a towel, then a cutting board (one you use for meat), then a layer of Press-N-Seal, sticky side up (or cellophane). One at a time, place your 4 chicken breasts onto the plastic and cover with a second piece of Press’N’Seal or cellophane, sealing the edges with plenty of room for the chicken to grow. Using a kitchen mallet (or something else heavy, like a small cast iron pan), whack the chicken until it is evenly flat and very thin (thanking your lucky stars that I suggested that towel on the bottom). Repeat with other chicken breasts.Heat your largest, flattest, shallowest pan over medium-high heat with 4 tablespoons vegetable oil and 1 tablespoon butter.Meanwhile (and before butter burns), run each piece of chicken through the breading station by dipping first in flour (both sides), then in egg (both sides), then in breadcrumbs (both sides). Do this quickly, but knock off the excess along the way.Place 1-2 chicken pieces (no crowding!) into the hot oil and cook for a few minutes on each side until lovely and golden. Remove to an oven-proof pan or dish and set that in the oven. As you finish each schnitzel, move them to the oven.Serve very soon after, with lemon wedges and optional chopped parsley, dill, and/or chives. (Sour cream and/or sauerkraut could also work here.) In a wide skillet or sauté pan, melt 4 tablespoons butter. Set aside.In a large bowl, whisk together 4 eggs and ½ cup milk.Mix in 2 cups all-purpose flour, 1 teaspoon salt, and some grated nutmeg with a wooden spoon, until there are no lumps. Set aside to sit for 15 minutes.Meanwhile, bring a large pot of water to a boil. Reduce to a nice simmer and stir in 2 teaspoons salt. Using a colander (or a spatzle-maker, or even a wide-hole cheese grater), push a third to a half of the batter through the holes directly into the water. Give it a gentle stir and in 1-2 minutes the noodles should rise to the top. Skim them off into the skillet with the butter in it. Finish all the batches.Turn the pan of melted butter on to medium-high. Sauté the spaetzle for just a few minutes, until there is a little brown here and there. Serve right away.

In a wide skillet or sauté pan, melt 4 tablespoons butter. Set aside.In a large bowl, whisk together 4 eggs and ½ cup milk.Mix in 2 cups all-purpose flour, 1 teaspoon salt, and some grated nutmeg with a wooden spoon, until there are no lumps. Set aside to sit for 15 minutes.Meanwhile, bring a large pot of water to a boil. Reduce to a nice simmer and stir in 2 teaspoons salt. Using a colander (or a spatzle-maker, or even a wide-hole cheese grater), push a third to a half of the batter through the holes directly into the water. Give it a gentle stir and in 1-2 minutes the noodles should rise to the top. Skim them off into the skillet with the butter in it. Finish all the batches.Turn the pan of melted butter on to medium-high. Sauté the spaetzle for just a few minutes, until there is a little brown here and there. Serve right away.

In a medium-style pot, melt 2 tablespoons butter over medium heat until melted.Add a thin-sliced yellow onion and cook, occasionally stirring, until beginning to brown.Add 1 peeled and diced Granny Smith apple and cook 2 more minutes, stirring.Add 1 pound shredded red cabbage, 1 tablespoon sugar, ½ teaspoon salt, a pinch of ground pepper, a pinch of ground clove, 2 juniper berries, 1 bay leaf, 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar, ¼ cup orange juice, and ½ cup water. Bring to a boil, reduce to a gentle simmer, cover, and cook for 1 hour. Make sure it doesn’t become dry or scorch.Meanwhile, in a little bowl, whisk together 2 tablespoons cornstarch with 2 tablespoons water. Set aside.When cabbage is soft, remove the lid and whisk in the cornstarch slurry. Remove the bay leaf and serve with optional red currant jam.

In a medium-style pot, melt 2 tablespoons butter over medium heat until melted.Add a thin-sliced yellow onion and cook, occasionally stirring, until beginning to brown.Add 1 peeled and diced Granny Smith apple and cook 2 more minutes, stirring.Add 1 pound shredded red cabbage, 1 tablespoon sugar, ½ teaspoon salt, a pinch of ground pepper, a pinch of ground clove, 2 juniper berries, 1 bay leaf, 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar, ¼ cup orange juice, and ½ cup water. Bring to a boil, reduce to a gentle simmer, cover, and cook for 1 hour. Make sure it doesn’t become dry or scorch.Meanwhile, in a little bowl, whisk together 2 tablespoons cornstarch with 2 tablespoons water. Set aside.When cabbage is soft, remove the lid and whisk in the cornstarch slurry. Remove the bay leaf and serve with optional red currant jam.

I would be tempted to try these with appropriate, seasonal berries, perhaps a few, pitted cherries or blackberries per dumpling in the colder months.

Peel and cut into quarters enough yellow gold potatoes to yield 2 cups when mashed. Place into enough cold water to cover. Bring to a boil and hold at a boil until the potatoes are about ready to fall apart. Strain and mash well (but stop before you have a gluey consistency, please).Meanwhile, clean and de-stem 12 strawberries of about the same size.To 2 cups of the potatoes, add 1 ¾ cups all-purpose flour, 4 tablespoons unsalted softened butter, 3 beaten eggs, and a generous pinch of salt. Combine to make an even dough.On a lightly floured surface, divide the dough into 12 even blobs. Roll out each blob into an approximate circle which will easily wrap around one of your strawberries. Wrap it around a strawberry and pinch the top together, creating as neat a ball as you can manage. Repeat with the rest of the dough and strawberries.Meanwhile, bring a pot of clean, salted water to a boil. Reduce to keep it at a steady simmer. Add the dumplings (without overcrowding the pan, which may require batches). Keep the simmer solid for 10 minutes, then remove the dumplings and set on a rack or a towel to dry.Meanwhile, melt 1 stick unsalted butter over medium heat. When melted, stir in 6 tablespoons breadcrumbs and 3 tablespoons sugar, stirring until breadcrumbs have browned but not yet burned.Serve the dumplings with the hot butter mixture drizzled over top and the top of the whole thing sifted generously with powdered sugar. For even more excitement, serve with a side of Buttermilk Ice Cream and Whipped Cream. In a small saucepan, heat ¾ cup half and half (or cream) with a generous 1/3rd cup sugar, 1 ½ teaspoons vanilla extract, and a pinch of salt over medium-low heat, until it is steaming. Stir until sugar has dissolved, but do not let mixture boil.Meanwhile, in a small bowl, scramble 4 egg yolks.When the sugar is dissolved, remove ¼ cup of this mixture and slowly whisk it into the egg yolks. Then drizzle the egg yolk mixture slowly into the pan of half and half, whisking as you add. Make sure you have no curdling at this point. Stir over medium-low heat until mixture coats the back of a spoon.Remove from heat and stir in ¾ c buttermilk (as full-fat as you can find it).Put mixture in a container with a lid and place in the fridge until chilled.Meanwhile, ready your ice cream machine.When mixture is chilled, continue with directions from your ice cream maker.When almost ready to serve, pour 1 cup whipping cream in a cool, clean, metal bowl. Add 1 tablespoon powdered sugar, a few drops vanilla extract, and a pinch of salt, and whisk on high until peaks form. Try to stop right before it becomes thick and buttery.Serve ice cream with whipped cream and a Strawberry Dumpling.

In a small saucepan, heat ¾ cup half and half (or cream) with a generous 1/3rd cup sugar, 1 ½ teaspoons vanilla extract, and a pinch of salt over medium-low heat, until it is steaming. Stir until sugar has dissolved, but do not let mixture boil.Meanwhile, in a small bowl, scramble 4 egg yolks.When the sugar is dissolved, remove ¼ cup of this mixture and slowly whisk it into the egg yolks. Then drizzle the egg yolk mixture slowly into the pan of half and half, whisking as you add. Make sure you have no curdling at this point. Stir over medium-low heat until mixture coats the back of a spoon.Remove from heat and stir in ¾ c buttermilk (as full-fat as you can find it).Put mixture in a container with a lid and place in the fridge until chilled.Meanwhile, ready your ice cream machine.When mixture is chilled, continue with directions from your ice cream maker.When almost ready to serve, pour 1 cup whipping cream in a cool, clean, metal bowl. Add 1 tablespoon powdered sugar, a few drops vanilla extract, and a pinch of salt, and whisk on high until peaks form. Try to stop right before it becomes thick and buttery.Serve ice cream with whipped cream and a Strawberry Dumpling.

February 7, 2024

Book Review: Biography of X

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comWe can definitely claim that Biography of X (not, NOT to be confused with The Autobiography of Malcolm X) by Catherine Lacey leaves plenty to be discussed about it. It also does some things that I have never seen before. Did I enjoy the book? To the extent that I was gawping at its literary acrobatics, but not beyond that. I mean, the writing was decent, but presented in a voice that would be appropriate for a biography even though it is a fake biography (aka a novel); it was stripped down too much to really hear much voice or style. It was much too long (and repetitive). It was largely set in the 70s-90s New York art scene, which is not only overdone but boring to me. The characters were miserable. And it did not deliver on many of its promises, including some sort of one-two punch of a twist.

It’s hard to describe Biography of X adequately. Most pitches and synopses do it straight, like this is some sort of normal novel. A super-famous artist dies. Her surviving wife is coming to terms with her and their relationship and decides to—despite X’s wishes—delve into X’s past and write the biography. But X had been secretive, enigmatic, a master of disguise for a reason, and what X uncovers—travelling to Europe, plunging into the cessationist, wall-partitioned South (this is alternative history)—could also undo her.

However, that little plot synopsis doesn’t really tell you anything about what you are about to pick up, if you choose to read this. It is one of those fake nonfiction books, first of all. So there is the first title page, Biography of X by Catherine Lacey, a novel, and then there is the second title page, Biography of X by C.M. Lucca, a biography. Both the novel and the “biography” include footnotes and endnotes. The book is also—I have decided this on my own and I am sticking to it—a collage. I’ve never seen a collage in the form of the long-form written word before, but it’s what we have here. Lacey has a new, strange process which includes taking real-life people, history, and quotes and giving them alternate realities, twists, and attributing them to other people. Lacey snipped up pop, art, and political history since the 1940s and pieced it back together with a weaving of a fictional history of the South (theocratic), North (communist) and West having become different areas? countries?, civil war, and the eventual reunification (in 1996, I think?). It’s hard to know, actually, when what you are reading is real or based on a real person or a real quote (without referencing the endnotes and Googling like mad). I can’t say for sure whether or not the woman could get sued for slander, but it is pretty… weird. And also feels art-elitist.

I read this book for a book club (surprise!). But I hadn’t finished it before the meeting and discussion, and I had an excellent excuse; because the paperback is coming out in February, the publishers were letting the hardcovers sell-out at the stores in January. I could not find a copy, even on Amazon and at the bookstore that was hosting the club. A few days before the club meeting, I wandered into an indie bookstore that happened to have one copy left on the shelves. And I paid full price at $30. Sigh. And this is not a read-in-two-days kind of book. In the end, I think I took five days, which is pretty impressive. Then again, I already knew, from looking at reviews, that there weren’t any of the types of surprises I was hoping for, at the end. So, the discussion was still interesting to listen to, midway through my read.

I will say this: the book—like the physical object—is beautiful. It lacks a dust cover… hallelujah! Instead, the cover has a fabric feel in a matte finish. The paper quality and color inside, the font choices, etc., are all noticeably pleasant. There are also ten pages at the beginning and end of the book that fade from black to white through shades of gray, and then from white to black at the end, to make sure we know, we feel, that we are stepping into this alternate reality, this distinctly fictional place. There are also photos, consistent with the biography idea, but I thought they were kinda sparse and low-quality, like I was reading Miss Peregrine’s School for Peculiar Children. And fake documents. Letters. Files.

There wasn’t one person at the group who defended the length of this book. At almost 400 pages, written in the style of a biography and jam-packed with details and allusions, it got bo-ring. Slow. And let’s not forget repetitive. A lot of us felt like there was a strong dropping-off point at about halfway through the book, after which a few things happened: first, we left the civil war and territories dystopia (which was interesting, for sure) and went to that art scene I mentioned. And never really went back; second, interviews with more and more people just get repetitive, not adding to X’s character or C. M.’s growth (unless to show her obsessiveness, but this was too big of an ask for the reader just for that); and third, that’s just plain too many biography pages for someone who’s not a fan. Especially when almost all the characters—especially X—are awful people (and C. M. is almost like a non-entity, which should have been a point, but felt flat to me). Lacey should have severely edited this book. (For example, I wrote “The End” before the last paragraph of my copy, partly out of frustration, by that point. It was like, she had two last paragraphs and refused to choose between them: the story of this novel.)

Or, instead of drastically cutting, in the words of someone at book club, “She’s young enough. She could have just written two books.” Yes! Because Biography of X does feel like two books, one being the biography of a megalomaniac by her mouse of a wife, exploring that ol’ art scene and the nature of love with someone incapable of love. The other book would be the strange, pieced-together, alternative history of a South that split and became totalitarian in the 1940s. This could have featured a girl who didn’t quite fit in and her attempts to survive or escape, ala Fahrenheit 451 or The Giver. Ultimately, it seems, many people don’t feel like these two stories came together. The one story, in fact, seemed to disappear, leaving the reader waiting for it to pop back up and assert its significance again—give us validation for having read all that stuff to begin with.

Which leads me to another point: I didn’t think X was consistent. She seemed, to me, like two different characters in these two different stories. I had a very hard time believing her prodigiousness or her anger or her sociopathy or her sheer talent, especially given her character as a child and a teenager and a young woman. I mean, I think we were supposed to assume that some of it was probably luck, as it always is, and also that no one quite had the whole story with her, but Lacey certainly could have dropped clues from her past that would translate to the kind of total-asshole and multi-area-genius that X is. Not to mention that she gets famous in various fields from scratch, with a new identity, multiple times. Don’t make me gag. I believe that is what many reviewers mean when they say X is “unbelievable.” It’s just not a realistic, or even possible, situation.

Let’s talk about the ending, without any actual spoilers. Um… there was an opportunity here for the artist-and-wife story to have a real, classic, mind-blowing twist at the end, you know, like Gone Girl. I was expecting it, actually, even though a part of me warned me that this is not what Lacey, with this work, is up to. But she gave us so many clues and such a set-up. I mean, there is a twist at the end, but it’s delivered is such a way that both C. M. and the reader receive it flatly. Which may be a problem with the biography medium. Or not. Still, I thought the clues (so many deaths and disappearances!, the South and its secret agents!) pointed toward even more of a twist, even more revelation about X in the eleventh hour. Nope-ity nope.

In the end, the book was about a toxic (or maybe abusive) relationship. Why, then, all the acrobatics? There was just way too much going on in this book. There are lots of interesting things going on among it all, but taken as a whole, it’s a cacophony, leading to confusion laced with exhaustion. And readers relegating it to a doorstop.

Here’s an interesting point made by someone at my book club meeting: though Lacey is pretty meticulous about her creation of an alternative American history, the North doesn’t change enough. Her very amazing example is the music. What would the music of the 50s through the 90s be without the South’s cultural influence? Certainly not what it is in Biography of X. Which could all just be interesting things to talk about, if everything else worked. But Lacey does do something obnoxious that I see many new books and movies doing, and that is painting the “other side” as all demon. Honestly, she does try to throw in a few lines later in the book, real off-handed, that are like “Oh, yeah, I can see things from their point of view too, and I’m not all perfect,” but it’s too little, too late. The South (even though Lacey is from Mississippi), Christians, religion even, are just monstrous. There is no nuance to it. Anarchy is cool. You follow Jesus, you’re gonna end up in a long, floral dress and bare feet, forced into marriage and child-bearing, illiterate and violent. Yeah, not a fan of painting people groups with such broad strokes (especially since I belong to both of these groups).

If you decide to read it, here is a list of things you might want to look up beforehand, at least to have a bit of knowledge:

Susan SontagRenata AdlerDavid BowieTom WaitsConnie ConverseSophie CalleClaire FontaineKathy AckerEmily DickinsonEmma GoldmanWim WendersDenis JohnsonPatti SmithBernie SandersKath BoudinFrank O’HaraJackson Pollock, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Calder, Marcel DuchampCindy ShermanAndrea FraseranarchycommunismFDRand I’m sure I’m missing many, many moreThe lesson here, with this list, is not to assume that any character is made up, and therefore that Lacey is referencing and saying something about them/it. On the other hand, I don’t think I would want to spend that much mind-space and research time on this book. I would have appreciated knowing a little more before book club, though, like who Connie Converse and Sophie Calle are.

Biography of X really is a work of collage, from misquoted quotes to famous characters rewritten to pop culture and news events from the time of writing (like Anna Delvey, NXIVM, and Theranos—which are not referenced, but used as plotlines). I just wish Lacey had made her collage about something more interesting, as the New York art scene is both overdone and boring to most people. Also, most of the allusions felt elitist, like only the cool kids would get it. I agree with lots of people that it had potential, but the characters were insufferable and unbelievable, the story of alternative America gets lost and feels pointless, and it’s just far too long, especially since it is written utterly and completely like a biography, so there is no “novel” about it, no drama. It reads like nonfiction because that’s how it’s supposed to read, but very little happens and it devolves into repetition. Then does it ever deliver on a real twist? No? X is just sadistic? It could have had a much more exciting ending, with the characters along the way involved in it. It was set up like they were still withholding from C. M., so what she could have discovered in the end could have really walloped us. As it stands, even the big ending was delivered quick and dispassionately, which was a let-down for me.