Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 15

February 2, 2024

What to Read in February

Valentines Day is a couple weeks away. Some of you will choose to ignore this holiday, and that’s one way to do it. Others of you will take the opportunity to put a wreath of hearts on your door, make a reservation at a fancy restaurant, and curl up with some chocolates and a good book. Or a good movie. Here are some of my favorite romantic books, as recommendations.

Jane Austen’s Emma, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Northanger Abbey. Austen wrote six novels, but I have only read these four. As far as I can tell, everything she wrote is solid. I haven’t even reviewed Emma, despite its being one of my favorite books. But I love it. The writing is old fashioned, sure, as are some of the ideas, but millions of readers around the world still enjoy reading Austen and there might be more Austen fans than of any other writer. Perhaps. Her writing is complicated. Witty. Full of interesting characters and twisty plots. These are classics for a number of reasons.

Another one of my favorite books is Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. It’s certainly not just a romance, with it mainly being about revolution, injustice, and politics with themes of judgment and redemption. But among its winding storylines and large cast of characters, there is more than one love story. They might tend toward the tragic, but they are compelling, heart-wrenching romances.

I see that my Valentines reading recommendations tend toward the, well, not new. But I have long loved many of these books, ya know, like a good marriage. I read the Brownings’ poetry in high school (Elizabeth Barret and Robert), and my favorite was Sonnets from the Portuguese, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning. They are pretty darn sentimental, I suppose, or at least dramatic, but love can be sentimental and dramatic, or at least it’s fun to see it that way. Perhaps it’s time I revisit this slim volume. Or Shakespeare’s Sonnets (especially, duh, number 116).

Perhaps you haven’t heard of it, but another favorite of mine is A Severe Mercy, by Sheldon Van Auken who was a contemporary of C. S. Lewis. This book (with a Christian bent that is from another place and time) is a man’s mourning and celebration of his late wife. It is a recounting of an exemplary, special love and marriage. It contains letters from Lewis, and England, academia, lots of time on the water… and is ultimately about faith/spirituality, which means it is not for everyone. For me, it’s a perfect mashup of things, and while their love is idealistic and super contemplative, it might be time for me to revisit this one.

And now we make a massive leap to newer books I’ve read in the past few years, which are all actual romance novels (including some historical romance).

If I’m going to relax my brain on a vaca, unwind with a romance, my favorite author for that so far is Emily Henry. I am not at all alone. Yeah, we’re not talking great literature here, or anything the least bit experimental, but there’s something fun about a more-expected and clear, playful and sizzling book like the ones I’ve read so far: Book Lovers, Beach Read, and People We Meet on Vacation. It’s fun, too, because she’s probably going to keep pumping these suckers out for years to come.

I also enjoy a Madeline Miller book, which is the historical/mythological romance genre and is a much weightier read than, say, an Emily Henry. She has two so far, Circe and The Song of Achilles, and because of the research involved (and the writing style), she takes much longer to write them. But I’m looking forward to her next project, which is rumored to be about Hades and Persephone. It helps that I have always loved to read about Greek mythology.

I kind of fell into reading Betting on You by Lynn Painter, just a few months ago. But when it comes to a light, enjoyable read that fits snugly into the romance genre (and YA, to boot), I am already a fan. A traditional back-and-forth-POV, hate-to-love romance, I thought it had good chemistry despite it being quite obvious.

Sliding up the highbrow scale a little is the first book of a series (which can be read alone), Jenny Han’s To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before. It’s another standard, YA romance. And it is written very well for what it is, has become very popular as a book and a movie. It’s cute, engaging, and goes down smooth.

There are a few Valentines-friendly titles that are coming in close on my radar/TBR, and those are Me Before You by Jojo Moyes, Persuasion by Jane Austen, and Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Saenz. Persuasion has a newer streaming series (which I liked, despite some bad reviews) and Aristotle and Dante came out at theaters this past summer. It was a good movie, though I have no idea now close to the book it is.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comEmily Henry also released a book last year that I haven’t yet read, Happy Place, and is set to publish another one later this year (which I will mention later in the year). Both of those will eventually go on vacation with me, most likely in the summertime.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comMoving on from Valentines, I just went to see American Fiction at the theater, last week. I had been looking forward to it for months because it was about a writer and also because the whole idea seemed amazing: a Black writer can’t convince the publishing and marketing world that his historical/mythology books are sellable, so to make his point, he submits a novel that flaunts the stereotypes of African-American writing, from gangs and violence to slave-language and absent fathers. It was funny and thoughtful, worked on many levels (dealing also with relationships, secrets, and death), and was well-crafted and acted. I have a review of it coming your way, but I was for once excited about an Oscar nomination when that came not a week later. Not surprisingly, the movie came from an actual book (about a book), Erasure by Percival Everett. Written in 2001, it has great reviews and would definitely be worth a pre-Oscars, pre-American Fiction read.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comAnd because of another movie, I am going to throw The Power Worshippers by Katherine Stewart out there. This month, the documentary (with Rob Reiner’s name on it) God & Country is coming to limited theaters, and I am looking forward to seeing it. It is about Christian Nationalism from both an outside-Christianity, and inside-a-dissenting-Christianity perspective, and it was based on the aforementioned book. If that interests you, then it’s a February option, for sure.

There are also a number of books that are causing pre-publication buzz, though I am behind on one of them.

The Atlas Complex came out a few weeks ago, the Olivie Blake trilogy conclusion to The Atlas Six and The Atlas Paradox. If you’ve been waiting, it is now your time. I do not see a date listed for the paperback edition.

February will see the publication of Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars. While I liked There There, I didn’t love it. I was looking forward to seeing more of Orange’s writing, but was a bit disappointed that he went with a follow-up to There, There instead of a new story with new characters. Maybe his growth as a writer will be apparent, even so. The book world tells us we’re going to like it…

I have recently joined several-too-many book clubs. I was banking on some of them being duds, but so far, they are not, at all. I have choices to make. Until then, here are the February reads for the clubs I may or may not be in, in a month from now.

The City of Brass, S. A. Chakraborty (then The Kingdom of Copper and The City of Gold, to complete the Daevabad Trilogy; speculative fiction book club)Little Thieves, Margaret Owen (YA for adults book club)

The Old Man and the Sea

(literary/banned books book club)The Seep, Chana Porter (speculative fiction book club (again, because of a scheduling thing))A Long Petal of the Sea, Isabel Allende (popular fiction book club)Trespasses, Louise Kennedy (contemporary fiction book club)Stay True, Hua Hsu (So & So bookstore book club)

The City of Brass, S. A. Chakraborty (then The Kingdom of Copper and The City of Gold, to complete the Daevabad Trilogy; speculative fiction book club)Little Thieves, Margaret Owen (YA for adults book club)

The Old Man and the Sea

(literary/banned books book club)The Seep, Chana Porter (speculative fiction book club (again, because of a scheduling thing))A Long Petal of the Sea, Isabel Allende (popular fiction book club)Trespasses, Louise Kennedy (contemporary fiction book club)Stay True, Hua Hsu (So & So bookstore book club)

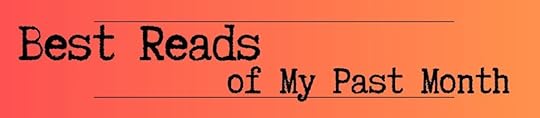

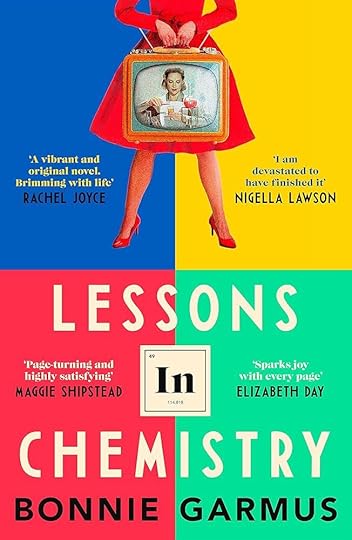

My favorite reads from my January reading are, drumroll…

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch. It is bleak, yes. But I thought it was an amazing book, as did the judges over at the Mann Booker Prize. Relevant. Deep. About motherhood and a realistic, dystopian alternate history. Beautiful writing, if a bit unconventional.

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, which is miles away from Prophet Song, in tone and style. It is a feminist book and there are some tough things dealt with, but the writing style is playful and I said it was like I was doing cartwheels while reading it. This one is concentrated on a strong and unique female character, a scientist in the ‘50s, and a surprise, single mother.

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell. And then I returned to a more literary read which also dealt with death and motherhood. For the love of Pete. A “novel of the plague” that is really about Shakespeare’s wife, almost completely made-up, but with a strong sense of historical fiction set in Renaissance England. I was very happy with most things about this book, including the writing style, which was both descriptive and active.

There’s a handful of movies coming out at theaters this month that I am really excited about:

God & Country (mentioned above)Argylle (which is about a writer of spy novels)Madame Web (which might just be me falling prey to Billy Eilish’s music in the trailer)Lisa Frankenstein (might be too gory for me, but we’ll see)Bob Marley: One Love

On streaming, I have just started Belgravia.

As for Valentines movies, the best rom-com of the past year (and maybe in awhile) has to be Anyone But You. Not perfect, perhaps, but both LOL, and a modern remake of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing.

Here are the romantic movies that I recommend year after year, time and again:

Once Sense and Sensibility (favorite)William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet (favorite)Ruby SparksEagle Vs. SharkSafety Not GuaranteedThe Princess BrideAmelieWayne’s World (comedy with some romance)Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World (graphic novel action)Stranger Than Fiction (favorite)Bend It Like BeckhamCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (wire fu)Angus, Thongs and Perfect SnoggingGarden StateMuch Ado About NothingMoulin Rouge!Monsoon WeddingA Midsummer Night’s DreamThe Best Exotic Marigold Hotel(500) Days of SummerPenelopeGhost TownYes ManEver AfterNotting HillMy Best Friend’s WeddingWhile You Were SleepingAll About SteveReturn to Me50 First DatesThe Wedding SingerMy Big Fat Greek Wedding (the first one only)Cyrano (which should have one like 5 Oscars last year)

January 31, 2024

Writing Prompt: First Line

What can I say? I smelled my hand the other day and came up with this first line and thought I would give it to the world as a writing prompt. You can write it down word for word and write from there. You can rephrase it (change the POV or tone or something) and go from there. You can sit here and think about the scenario (brainstorm, like in your head or with words) and come up with your own first line from those thoughts.

First line:

The back of my hand smells like wood smoke, but I don’t know why.

January 30, 2024

Read Me: First Lines of Biography of X

Normally I would post this as a “First Line” and make it pretty, like a meme. But it wasn’t the first line, exactly, that I wanted to feature, here, as it is the first paragraph that is notable, as a whole. And it would not fit in a neat, little, pretty box (literally, digitally). To be honest, I am still near the beginning of this book (despite my goal of being done with it tomorrow) and I have yet to decide what rating to give it. But I do think it’s worth our time to pause here over the first bit and consider what we can enjoy about it and also learn from it. (trigger warning: suicide)

“The first winter she was dead it seemed every day for months on end was damp and bright–it had always just rained, but I could never remember the rain–and I took the train down to the city a few days a week, searching (it seemed) for a building I might enter and fall from, a task about which I could never quite determine my own sincerity, as it seemed to me the seriousness of anyone looking for such a thing could not be understood until a body needed to be scraped from the sidewalk. With all the recent attacks, of course, security has tightened everywhere, and you had to have permission or an invitation to enter any building, and I never had such things, as I was no one in particular, un-called for. One and a half people kill themselves in the city each day, and I looked for them–the one person or the half person–but I never saw the one and I never saw the half, no matter how much I looked and waited, patiently, so patiently, and after some time I wondered if I could not find them because I was one of them, either the one or the half” (p7).

Repost: Mammothuan

I may have written this post in 2014, but I haven’t done much in a decade to learn from it. Honestly, I’m personally glad I came across this bit of wisdom, right now. Because that’s what it is: a bit of wisdom I gleaned from a simple interaction with my fourth-grade daughter (who is now in college). It pertains to the writing life, the reading life… to any life at all. And, like one reader did, please don’t take this as something that you must be a mom to understand: my bafflement here is not at my own child, it is at myself. How could I have let my life and mind-space get so needlessly complicated?

A few days ago, my nine-year-old daughter received a letter in the mail. It was from her last year’s teacher. Now, my children are in a smallish Montessori school, which means that they switch teachers and classrooms only every three years, and each of these transitions is somewhat of a big deal. Both my kids are transitioning between “houses” over the summer, and so it was natural and touching for Miss Holly to jot a note to Windsor telling her she would be missed, come and visit, and hope her summer was going well.

Windsor came in the front door grinning, because who doesn’t love to get honest-to-goodness mail, set the bills and junk-mail down, and tore into the envelope. She was touched by the letter, I could see, and felt special. She told me who the letter was from, let me read it, and then took the note, walked past me, disappeared into her room and shut the door. Within twenty minutes she was back by my side, where I was now doing something in the kitchen, and she wondered, Mom, could she have a mailing stamp and what did I think that said for Miss Holly’s return address road? I fished the stamp out from our bill folder, handed it to her and–to my utter surprise–she stuck it on the front of an already-addressed and sealed letter, walked out the front door and down the drive, and dropped the blasted thing in the mailbox with the flag up.

You’ve got to be kidding me, right?

Aren’t things like that an event?

Doesn’t it take time and effort to respond to a nice letter?

Didn’t she have to think about it?

Plan it out?

Schedule it?

Miss the intended date and then feel guilty about it?

It was one of those lessons that they say come to you “out of the mouth of babes” or “when you have children,” the “be as one of these” scenario. Here I am, day after day with my heaped-on-heap list of things to do, weighing the must-dos with the must-do-nows, toppling my bucket lists for the tyranny of the urgent, and sighing myself to sleep at night cuddled up with the beasts of regret, intentions, and unrealistic expectations. And she–and she!–just thought, “I should write her back,” and found the accessible tools and wrote a simple response and popped it in the mail. I can’t quite aptly express to you just how much someone like me has her mind blown by this scenario.

Let’s break it down.

She found the accessible tools. There was no trip to the stationary store. There was no jotting of the trip to the stationary store on the calendar. There was no telling herself to remember to later jot on the calendar a trip to the stationary store. She found a blank card or some nice paper, fluffed it up a bit, and grabbed a pen out of her pen cup. Then she made a trip all the way to the other end of the house for a plain envelope, the kind you might mail a check in. Holy moly! Why have I never thought of this? Why have I been making such a big, freaking deal out of things when I often have the resources right there in front of me? Who cares if they aren’t theme- or occasion-perfect? If it’s going to still express care to someone or get me the same results and I have it on hand, for pity’s sake…! Let’s just cut through all the freakin’ fanfare…! (I can no longer finish my sentences, I am so overwhelmed.)

She wrote a simple response. You know, like the old acronym; Keep It Simple, Stupid. Windsor is known for her lovely, hand-made cards and gifts, but somehow she still doesn’t expect a masterpiece out of every card. She wanted to reach back out to her teacher, thank her, and share the warmth of her feelings. This did not, in this case, require glitter, stickers, lace, doilies, scrapbook paper, stencils, stamps, a mixed CD, a Power Point, a parade, or a circus. I can’t tell you how many times lately I have let some odd expectation build up in my head until I think it might explode, and a few times I just sent one itty-bitty text and the whole thing shrunk back to size, like I had popped a hole in a giant balloon. I was going to save up money, research restaurants, interview friends for the perfect gift, buy a small gift, wrap it, and take someone out to lunch, when what I wanted to accomplish was managed with a look in someone’s eyes and a few heartfelt words. OMgoodness. I, again, am at a loss for words.

She popped it in the mail. I don’t even know if she slid her shoes on. She just did it. And I could once again underline the lack of fanfare and the simplicity of the whole thing, but this time I want to concentrate on her attitude. She just popped it in the mail. Like tra-la-la. She might of skipped. She often does, her extremely long, blonde hair trailing out behind her and her twenty-neon-colored tennies with her mismatched socks blurring by. Sometimes, doing things as an adult is made much more difficult than it needs to be, simply by our mindset, our attitude. It’s called, of course, “building something up in your head.” I have had a lot of this going on lately, as my husband and I have reorganized six out of ten of the rooms of our house, and are working on the seventh and eighth. By the time you have a chest-high stack of papers and office supplies blocking entry to the laundry room, you also have what we know as a mind game. There are crasser words for it. And when you think of the project, even think of thinking of it, your whole body tightens up like a cat on a ridgepole. You can’t even imagine managing the pile. How could you? Where would you start? Why did you do this in the first place? What have you done? It will just have to stay there forever, and you can take the dirty clothes to the laundromat, until one day you go to reach for the next Harry Potter and the whole thing comes crashing down, breaking both your legs and burying you so that you can’t get to the phone and when they finally find you, you have suffocated and everyone’s embarrassed to come to the funeral because who dies like that, in their own filth? Arrrrgh! It’s a deal, alright; I’ll give you that. It’s re-organizing the office. But it’s only that. And what it most certainly is NOT, is your worth. Take one from Windsor. She’s not losing any sleep over a letter that wasn’t written.

Which, ironically, makes her the mostly likely to have the letter written, sealed, and sent.

Sweet dreams, Win. And you, dear reader, take one from me and my being the mother of some wonderful kids: when you have some sort of writing project, use the accessible tools, keep is simple, and pop it in the mail. Because Windsor is working on her novel, and if you can’t get your stuff together before she turns ten, she’s going to steal your agent and your publisher.

January 26, 2024

Book Review: Lessons in Chemistry

Image from Walmart.com

Image from Walmart.comI felt like I was doing cartwheels while reading Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, and I mean that in a good way. Or like I was watching Garmus do cartwheels. Her writing style, characters, and plot are so free-wheeling. The subject matter is often sad, serious, and even brutal, but somehow this book is both historical and feminist, and light-hearted and playful. Technically, it’s even magic realism, though I don’t hear anyone calling it that, because it’s also full of accurate and honest portrayals as well as “interesting factoids” (a la Olive from Ant Farm). This book is far from being just one thing. It is a fun story with that classic magic realism climax. It is a revealing of what it was like to be a woman in America in the 50s (historical fiction). It is a romance. It is feminist. It is well-written, popular fiction. It involves chemistry, rowing, dogs, cooking, television… It is (very much) a story about relationships of various stripes, especially female relationships. It is a portrayal of trauma (many traumas, really). It is a sketch of a unique and forceful character. It is replete with oddballs. And it is anti-religion (my least favorite part) in its pro-science-ness.

Elizabeth Zott is a chemist. But it’s the 50s and she can’t get no respect, especially when her path to a PhD is blocked by the patriarchy in a brutal and unfortunately familiar way. Now, she’s a lab tech who most coworkers assume is a secretary, and who absolutely none take seriously. She’s too pretty—and too female—to be a genius, after all. But Elizabeth Zott isn’t going to take any of this lying down. She is determined—and sometimes oblivious. Then one day she goes barging into the lab of a famous, revered, young chemist to demand more supplies and ends up setting off on an adventure that will take her heart and life in directions that she never saw coming.

This book had been so present in every bookstore and store around the end of 2023, had been mentioned on every year-end book list (though it was published in 2022), lingering at the edge of every bookish conversation… I was annoyed, actually. It was the kind of book that looked like one I wouldn’t like. I was unclear as to how good the book was as opposed to popular. And I had already been burned, months ago, by Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us after falling prey to the it’s-everywhere syndrome. (Sorry, Colleen, but not my jam.) My daughter said the same thing: she couldn’t get away from this book. And then I realized I had some winter blues going on, and decided to try out some local book clubs. The second one I penciled into my calendar was currently reading—duh, duh, duh!—Lessons in Chemistry. Not a shock, unless I was shocked the club hadn’t gotten to it yet. Now curious as well as annoyed, I purchased the book and started reading, hoping for a good book and a good group of new people.

This is the first ever book that I am reviewing after discussing it with a book club, with a group of people. I imagine this will happen in the future, but I reviewed Of Mice and Men years before I went to the first book club meeting of my latter life (like one week ago). In theory, I like the idea of reviewing on the blog before attending the discussion. I also like the idea of finding out what others think, first, just like how I like to check out the reviews on Goodreads, etc. before I finish up and post almost any review. I knew how I felt; I could retain that, right? Yeah, I think so.

Alternative cover image from Amazon.com

Alternative cover image from Amazon.comFirst and most obvious thing at group: I was not at all alone in a negative read on the cover (see image above). I don’t recall anyone out of the group of around 20 who defended the cover. Most people thought it looked like a romance when they saw the cover, and several said they dismissed the book because of that. One man said he hid it while reading in public. Everyone agreed that the cover did not reflect the content and wished that the publisher in America had gone with a different cover. And one woman said she noticed that many of the lowest reviews were from people who bought the book based on its cover and were disappointed it wasn’t a titillating, easy-read, romance. (See cover gallery HERE.)

I enjoyed the book. It was a page-turner and very easy to read. The language was playful, but mostly the story-telling was playful, and I had fun going with Garmus on her little adventure in literature. I liked the magic realism bits (I might as well tell you that the dog is a POV character) because I love magic realism. I also loved the insanity and neatness of the crash-bang ending after all the bits and pieces making their way into a tapestry that you don’t see coming until—!, because that is something I love, too (which someone at book club pointed out often goes hand-in-hand with magic realism). I appreciated the feminist aspects, partly because I have an interest in history and also because there are still echoes of everything she writes about in society today. I could relate to many of the obstacles and issues, many with the volume turned down. Elizabeth Zott is a super interesting and special character. You haven’t met her before in literature. She’s something else. (It is possible that she is on the spectrum or neuroatypical, but it’s not for sure.) I always love a cast of interesting characters, too, and this book is chock full of both heroes and villains, though none of the good guys lack foibles. All good, right?

Well, besides the few missteps that kept this book from my “perfect” or “favorite” list, there is also the not-so-small matter of how Christianity and religion are portrayed in this book. I don’t have a problem with Christianity being portrayed negatively in literature, exactly. I might be disappointed, but not surprised or even turned off by it. However, I have seen a trend lately both in books and in other media of turning the religious types into one-dimensional monsters while the rest of the characters get a much more rounded treatment. Lessons in Chemistry tries to give us just one character who is both of the faith and a “good guy,” but there’s only one way to do this in this book: make him a nonbeliever. Yes, a religious person without faith. (Actually, there was really more than one character like this.) Why is this the only way? Because all believers are dumb as rocks, even if they’re not monsters. The two main characters in Lessons in Chemistry appear to reflect the voice of the author here: only the gullible, uneducated, and unintelligent believe in a God or gods, especially these days. Cuz science. Which ignores reality, quite frankly. Ignores history and many of the smartest people in the world (including many, many scientists) who do believe in God and/or the supernatural. So I was totally offended by this. How could I not be? Garmus was basically calling me a moron while I was reading her little book (which I was otherwise enjoying)..

Still, it’s a fun book and I enjoyed it on many levels. I really thought its strongest points were regarding female relationships. Female-male relationships, some; romantic; partner; and friendship. Mother-daughter. Woman to herself. Woman to society and institution, like crazy. And definitely women with each other, which included both positive and negative female-female relationships. Essentially, Elizabeth Zott is this amazing Amazon woman who emerges from a lifelong stew of toxic relationships and—one little shaft of light at a time—she learns her lessons in interpersonal chemistry, which turns out to be the only thing that will save her and—who could believe it?—will make it worth all the pain. I especially keyed into the female relationships that were competitive, manipulative, and jealous. You don’t see those in books as much, but it was something I really struggled with growing up and have some more recent battle-scars from dealing with. I also thought this book shone when it came to characters changing and learning and growing. With the exception of maturing into belief (as she would see it), everyone except the real baddies were capable of improvement.

It’s a punchy book. Has great dialogue, including a lot of wit and humor. Interesting and a fun ride. The characters and voice are pretty amazing. There’s just the tiniest bit of magic realism (which is basically how magic realism works). Garmus really tackles some feminine issues, like equality in pay, domestic expectations, and female-female competitiveness in places where allies are needed. And many more. She’s a little hard on religion and Christians are monsters and unintelligent instead of dimensional characters like everyone else, which I have found in lots of stuff lately. Oh, and I forgot to mention that her foreshadowing is lacking hard-core in one of the main plots, so that’s a jaw-dropping moment that was handled really awkwardly (and my book club all agrees with me on this). I would give this book a big recommend, though, just like most people who are passing it around. Most readers will like it. I enjoyed it, for sure. Sorta similar to Where’d You Go, Bernadette?

This is Bonnie Garmus’s first novel, though she is no spring chicken. Her age and its success reminds me of Where the Crawdads Sing and Delia Owens, except hopefully we won’t find out that her book is a thinly veiled retelling of her complicity in a murder. Also, Owens was a naturalist writing about the natural world in a way that only a naturalist could. Garmus is not a chemist (she studied creative writing), yet appears to be a chemist by the way she writes about it. I guess that’s how research works. And imagination. Garmus is a rower and dog owner and mother, though, a Californian (who has lived elsewhere, too). She is also an open water swimmer, which is pretty cool but irrelevant to this book. She did work “widely” in the tech and medical fields, I think as a copywriter. (I can’t tell if those things go together, in her bio.)

Let’s see where she goes from here. She says she is writing another novel.

“She didn’t want children—she knew this about herself—but she also knew that plenty of other women did want children and a career. And what was wrong with that? Nothing. It was exactly what men got” (p14).

“Even the women who wish to be homemakers find their work completely misunderstood” (p26).

“And then there was the illogical art of female friendship itself, the way it seemed to demand an ability to both keep and reveal secrets using precise timing” (p48).

“Sure, grit was critical, but it also took luck, and if luck wasn’t available, the help” (p74).

“Because while stupid people may not know they’re stupid because they’re stupid, surely unattractive people must know they’re unattractive because of mirrors” (p150).

“’Probably going to argue you don’t have time.’ / ‘Because I don’t.’ / ‘Who does? Being an adult is overrated, don’t you think?’ he said. ‘Just as you solve one problem, ten more pull up’” (p160).

“’Life’s a mystery, isn’t it? People who try and plan it inevitably end up disappointed.’ / She nodded. She was a planner. She was disappointed.” (p210).

“’Men and women are both human beings. And as humans, we’re by-products of our upbringings, victims of our lackluster educational systems, and choosers of our behaviors. In short, the reduction of women to something less than men, and the elevation of men to something more than women, is not biological: it’s cultural’” (p237).

“’Because quite often the past belongs only in the past.’ / ‘Why?’ / ‘Because the past is the only place it makes sense’” (p246).

Image from Penguin Books

Image from Penguin BooksPerhaps you already saw the 8-episode miniseries on Apple+. Perhaps it’s what has made the book extra-popular lately. Either way, both have been super popular, talked about by many people I have encountered. Here’s the thing: as some gal at book club kept saying, you should probably think of the show and the book as two different entities. I have heard through the grapevine that Garmus is not happy with the series, and I would understand completely. It’s one of those adaptations that completely misses the point of the book, discards the spirit and soul of the original work (like Anne with an E). Sure, there are some similarities in character names and events, but the series didn’t even keep the basic personalities of most of the main characters, including Elizabeth Zott (by my reading). It was impossible for Brie Larson to even play Elizabeth Zott as she should have been, because the plot changes and dialogue writing made her into a different character. There were whole plot lines scooped out, only to be replaced by plot lines that introduced entire, other issues (like race relations in the 50s). This meant that crucial themes were replaced. And my favorite character was replaced by someone else with her same name. Why? No clue. And the way the magic realism (read: the dog) was dealt with was pretty darn weird. Definitely disappointing.

Funny thing, though. I would not say this series was bad. Actually, it was pretty good. But if you are looking for more of the book, don’t look here. Maybe like Rowling or Riordan, Garmus will get a chance in the future to remake the book with its soul still intact. Until then, go ahead and watch the series because it’s pretty good, just not expecting Garmus’s story. Also, if you are not going to read the book, it won’t ruin anything for you. But trust me on this: it’s not the same thing, at all.

January 24, 2024

Book Review: Mothman’s Curse

Mothman’s Curse by Christine Hayes is a fun, little, middle grades read and I would definitely recommend it for MG readers (maybe even late elementary school) who like mysteries and spooky stuff. It is somewhere in the neighborhood of Scooby Doo but with tween and younger protagonists, but when reading that level of creepy in novel form, it could be a little too scary for some kids. I don’t want to overdo it: though there are supernatural things and death, it is pretty lighthearted and age-appropriate; It’s no Flowers in the Attic. I had a fun time reading it, which means that the writing itself is acceptable and I kept turning the pages to see what happened with Josie and her siblings.

Josie and her little brothers—the precocious Fox and inventive Mason—live on property with their dad’s auction house in Ohio. When they encounter a haunted camera that prints pictures of a dead man, they are thrown into a mystery that weaves back to the ol’ Mothman stories they heard about growing up. Still dealing with her mother’s death and with feeling like the un-notable sibling, Josie would do anything to protect her family. And with a curse and a mystery hanging around, that might mean any number of things.

I found this book while looking for Mothman literature. I am editing the first book in a YA trilogy that I am writing, which has a moth-man character in it. While I don’t actually want my moth-man to be the Mothman, I decided I should familiarize myself with the legend and where that legend has gone. This is the first Mothman book I bought and read, partly because it was the most affordable and readily available. Actually, there aren’t that many out there, to begin with.

One of the things reviewers say a lot about this book is that they like the family dynamics. Yeah, mom is dead (isn’t she always?!), but dad is around (until he has to be removed enough to allow the kids room to make an actual story here), as well as an aunt and uncle, as well as familiar neighbors. And the relationship between the three siblings is also strong and loving, though not uncomplicated. I do appreciate functional families in literature, especially in children’s lit and especially because they are rare. Josie, etc. have enough issues; family can be a strong point. Plus, the characters are cute, and engaging enough for this reading level.

As I mentioned above, though there is a Scooby-Doo thing going on here, we are not going to find out in the end that Old Man Winters is under the Mothman mask. This isn’t giving anything away. This is a story that involves actual (fictional) supernatural monsters and events. Think Casper, but a little creepier. And it’s not set in some fantastical world or anything. Hayes was inspired by the legend of Mothman, which is featured in this book (and added to tremendously—Mothman is kind of a thin tale, actually, compared with, say, Bigfoot). It’s Ohio. It’s modern times.

And, yeah, it’s not really for middle-aged women, but it’s written well enough that an MG-reading grown-up could read it and like it and recommend it at the library or in the classroom or whatever. In other words, it’s not going to be an unpleasant experience for anyone, unless you scare really easily. Or if you don’t approve of stories about the darker side of the supernatural. Mothman’s Curse scares you. Makes you think about family. Tells a fast-paced, adventure story to tweens.

January 23, 2024

Book Review: Prophet Song

Holy crap, this is an amazing book. I kinda feel like it’s been done—family at the outbreak of society’s collapse/civil war, or stream of consciousness, or modern family in dystopian times—but it also has not been done. For one, the maternal perspective in Prophet Song by Paul Lynch is pitch perfect, intimate, and novel (hard to believe he is not a mother, actually). Also, it’s like hero-meets-antihero because everyone is so real. It is a bleak read (a word that gets used to describe this book a lot). Brutal, even. But it is also contemplative and important. And the language is beautiful, if perhaps over-shooting it sometimes. I kinda read this book on a whim when I saw that it won the Booker Prize last year, but I am so glad I picked it up.

It might be the future or it might be right now, but it’s definitely Ireland and it looks a lot like our current world. Until Eilish’s husband goes missing and we start catching little clues around every corner. There has been some strife in politics, leaving a party in power that is predisposed to overreach their authority. And since Eilish’s husband worked for the people and worker’s rights, he is first in line for questioning and incarceration. But people don’t yet understand what is happening, and as each new atrocity begins, engulfing her baby, teen children, senile father, neighbors and co-workers, as well as her rights and sense of normalcy, how does she respond to that which she cannot confirm? To that which she doesn’t know or understand? Caught between the painfully slow slide of a democracy into something else and her normal life as a scientist, daughter, and mother, Eilish sometimes has to make decisions before she’s even noticed there is a decision to make… and then live with the often-terrible consequences.

So, I added to the Best-Ofs List: 2020s, at the end of 2023. Mostly, I added some amalgamated top-ten lists. And then I thought, well what about the big prize winners? I added those to the list too, and even inserted them into my 2024 pipe-dream TBR at a rate of one a month. For some reason, Prophet Song was the first one to plop onto January, having won the Booker Prize in 2023. I mean, I hadn’t heard that much about it, though. I mean, it wasn’t on all the best-ofs list for the year. I hadn’t noticed it at all the bookstores. I mean, it was no Lessons in Chemistry. But 2023 was pleasantly-surprisingly chock full of great books and recommendations and enthusiastic readers. There were bound to be more great books from 2023 than I could read in a year’s time.

I didn’t start out loving Prophet Song, or even appreciating it. First, the cover struck me as lackluster and the title, well kinda off-putting. I mean, the title sounds like it could be a few different things, but none of those impressions were Irish, stream-of-consciousness, literary, dystopian, mom lit. And then I started reading. Sigh. I think that one of the main reasons series have become so popular is that beginning a new book with a new voice and a new setting and a new tone takes work. And when an author is doing something, say, experimental or even just rare, it makes starting even more work. Prophet Song is literary to the core. It is told in first person stream-of-consciousness. It is also present tense. It also lacks usual grammar in many aspects. There are periods and capital letters, occasional paragraph breaks and even chapter breaks, a random comma, but besides that, even some of the possessive and contraction apostrophes are missing, let alone all the usual periods and commas and whatnot. I understand why you would use run-on sentences and play with verbs and things if you are trying to inhabit Eilish’s head, sometimes stating things in interrupted thoughts and innovative phraseology or, how would I say this?, misused words (in a way we all must use whichever word creates the most meaning in our thoughts and then cast it off). But no quotations marks? Why no paragraph breaks where they would usually be? I had a hard time accepting that a little more clarity would mess with the mood and stream-of-consciousness of the book, since it would have made it much easier to read. In fact, I’m sure many people begin to read the book and are like nah. Way too much work. Personally, I moaned and then I got used to it. I would say I even grew to appreciate the choices. But I do think Lynch could have pulled back on the bizzarro-reigns just a little bit, making it easier to settle into, and yet retaining its intimacy and reality. Do I think Lynch should have given in to some conventions to make it more accessible? Yes, I do. Could he still have been innovative and created the same mood? Yes, I think he could have, just with a little lowering of his pinky on the teacup.

This book would be great for teaching in either literature/writing or in history. While it is alternate history/dystopia, the story is also both the distillation of the experience of millions (?) of people throughout history and a warning-bell for the future. I couldn’t help thinking, “Well, I’m glad I’ve read this book, because if this sort of thing starts happening around me, maybe I’ll have some insight.” And it’s not hard to believe this would happen to me, soon, in this country. But then there is also the dimension of this book being great literature. The Scottish and Irish writers seem to be throwing a lot of slam dunks lately, but this writing is amazing. It’s lyrical. And surprising. And deep. And creative. And artistically beautiful. The plot is slow and, in some ways, unconventional (in that literary-not-seven-point way), but the tension is incredibly tight and even. The characters are complicated, well-drawn, and sympathetic. And talk about themes! You could sit around in a book club circle and talk about this book for hours, just based on theme alone. What is Lynch saying? Who is right? Who is wrong? Where have we seen this before? Where is it happening now? Could it happen to us? How would I react? Did Eilish respond how any family woman would have to? Were her feet “rooted,” as she asserts at one point? How do everyone’s perspectives change as more about their reality unfolds? Was it possible for them to predict what would happen? How could they have changed their outcomes?

Anyway, this was a grind, because the characters are being ground ruthlessly by the wheels of politics and the mechanisms of power as lived out in the lives of the normal Joes of society. Like I said, it is bleak and brutal, but it is also beautiful and powerful and important. I know that not everyone is going to pick up this book or make it through this book, and yet I keep recommending it to those who I think might. Because it is a great book and it deserves to be read and celebrated.

I can’t do much better than what it says on Lynch’s website about the book: “Exhilarating, terrifying, and propulsive, Prophet Song is a work of breathtaking originality, offering a devastating vision of societal collapse and a deeply human portrait of a mother’s fight to hold her family together.”

Paul Lynch is still fairly young, but has been publishing to critical acclaim since his first novel in 2013, Red Sky in Morning. His other books are The Black Snow, Grace, and Beyond the Sea. I don’t know how I can’t be curious about his other books at this point. All of them were widely lauded, they just hadn’t crossed my radar, so much. He has lived a very normal life, in Ireland, with two kids and a divorce, having not graduated from college, and been a film critic before becoming a writer. Yet, somehow, in that lack of fanfare, genius was growing.

“She checks herself then, almost laughing, this universal reflex of guilt when the police call to your door” (p2).

“…but tradition is nothing more than what everyone can agree on—the scientists, the teachers, the institutions, if you change ownership of the institutions then you can change ownership of the facts…” (p20).

“…if you say one thing is another thing and you say it enough times, then it must be so, and if you keep saying It over and over people accept it as true—this is an old idea, of course, it really is nothing new, but you’re watching it happen in your own time and not in a book” (p21).

“Sooner or later, of course, reality reveals itself, he says, you can borrow for a time against reality but reality is always waiting, patiently, silently, to exact a price and level the scales…” (p21).

“I would rather die than see his absence parading all day in front of the children” (p40).

“…the words leave the mouth and the mind follows after the words and some sense of understanding is made” (p48).

“Memory lies, it plays its own games, layers one image upon another that might be true or not true, over time the layers dissolve and become like smoke, watching the smoke that blows out her mouth vanish into the day” (p72).

“Soon he will walk and then he will run and the hand that pulls on the hand of the mother is the hand that will pull to let go” (p95).

“I wish you would listen to me, Aine says, history is a silent record of people who did not know when to leave” (p103).

“There is memory in weather” (p136).

“…she sat with Larry and felt the quickening of the child that would be Mark, the first flutterings as though the child were growing wings to take flight from inside her” (p137).

“…something breaks inside the man who learns he could not protect his family, it will be best if he doesn’t know” (p140).

“They are calling it an insurgency on the international news, Molly says, but if you want to give war its proper name, call it entertainment, we are now TV for the rest of the world” (p160).

“…if he’s not false then it is the world that is false, there is always someone else to blame” (p164).

“…the dust laying itself down upon the years of their lives, the years of their lives slowly turning to dust…” (p176).

“…it is as though she were looking out upon something she had been waiting for all her life, an atavism awakened in the blood, thinking, how many people across how many lifetimes have watched upon war bearing down on their home…” (p182).

“History is a silent record of people who could not leave, it is a record of those who did not have a choice, you cannot leave when you have nowhere to go and have not the means to go there, you cannot leave when your children cannot get a passport, cannot go when your feet are rooted in the earth and to leave means tearing off your feet” (p185).

“”…this is not the news, this is not the news at all, the news is the civilian watching the soldier outside her home and he lolls on a sandbag playing with his phone, the news is the assault rifle resting against the sandbag” (p189).

“…a youth who stands alone at the junction and looks as though he is awaiting command to place his weapon down and go to school…” (p193).

“We have entered into a tunnel and there is no going back, she says, we just need to keep going and going until we reach the light on the other side” (p197).

“…you never lose, you either learn or win…” (p197).

“…he will always be here because the love we are given when we are loved as a child is stored forever inside us …. his love fo you cannot be taken away nor erased, please don’t ask me to explain this, you just need to believe it is true because it is so, it is a law of the human heart” (p198).

“…seeing how they have made an end of death by meeting it with death” (p202).

“…one moment you are pruning trees and the next you are an improvised ambulance driver, wondering what it is the man will do with this when he tries to sleep tonight, watching the small child with the face full of shrapnel he helped carry into the van, watching it replay in his mind for the rest of his life” (p245).

“…she closes her eyes and cannot think what to do, the heart has grown too sick for thinking, the heart now in a cage” (p276).

“There should be nothing on the other side but the edge of a cliff that begins the long fall down into nothingness but instead the road continues past the border…” (p286).

“…I don’t see how free will is possible when you are caught up within such a monstrosity, one thing leads to another things until the damn thing has its own momentum and there is nothing you can do…” (p302).

“…wishing for the world its destruction…” (p304).

“…it is vanity to think the world will end during your lifetime in some sudden event, that what ends is your life and only your life…” (p304).

“…the end of the world is always a local event…” (p304).

I can’t imagine doing this book justice as a movie or TV series. It would make a good movie or series, actually, but the movie couldn’t be better than the book, nor could it really capture the soul of this book, which is necessarily bound to the language. Just sayin’.

January 22, 2024

Read Me: To a Mouse

I am trying out some book clubs (which I will blog about shortly). The very first one that I went to had just read Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, which was convenient because I read it a few years ago and just read my own review before checking the group out with pretty minimal investment. Turned out to be an amazing group that I will probably join more permanently, but that’s not the point. During the discussion, the title of the book came up and I realized I had not addressed it in my review, even though I had looked it up. The title comes from a Robert Burns poem, which in turn inspired a common phrase. Which came first, the phrase or the book title? I dunno, but I suspect the phrase would have been common enough at the time of publication that people would have understood the allusion and the meaning, though I’m not sure.

It was also pointed out at book club that Burns Night is just around the corner. For those of you who haven’t heard (everyone in our group of around a dozen minus one), Bruns Night is a Scottish holiday to celebrate the National Bard himself, Robert Burns. Traditionally, they celebrate Scottish culture on January 25 (three days away!) with poetry reading, haggis, Neeps and Tatties (a dish of turnips and potatoes), and whiskey. You might also want to do a little research into Burns and—I can only imagine—sing all the verses of “Auld Lang Syne.”

Since his work is in the public domain (having written in the 1700s), I am going to share “To a Mouse” with you in honor of Of Mice and Men and Burns Night.

Wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie,

O, what a panic’s in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi’ bickerin brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion

Has broken Nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle,

At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

A daimen-icker in a thrave

’S a sma’ request:

I’ll get a blessin wi’ the lave,

An’ never miss ’t!

Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!

It’s silly wa’s the win’s are strewin!

An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,

O’ foggage green!

An’ bleak December’s winds ensuin,

Baith snell an’ keen!

Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste,

An’ weary Winter comin fast,

An’ cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel coulter past

Out thro’ thy cell.

That wee-bit heap o’ leaves an’ stibble

Has cost thee monie a weary nibble!

Now thou’s turn’d out, for a’ thy trouble,

But house or hald,

To thole the Winter’s sleety dribble,

An’ cranreuch cauld!

But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

Still, thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna see,

I guess an’ fear!

Alright, alright. I’ll also include a translation. This is the Standard English translation posted at Loudon County Public Schools online.

Small, crafty, cowering, timorous little beast,

O, what a panic is in your little breast!

You need not start away so hasty

With argumentative chatter!

I would be loath to run and chase you,

With murdering plough-staff.

I’m truly sorry man’s dominion

Has broken Nature’s social union,

And justifies that ill opinion

Which makes you startle

At me, your poor, earth born companion

And fellow mortal!

I doubt not, sometimes, but you may steal;

What then? Poor little beast, you must live!

An odd ear in twenty-four sheaves

Is a small request;

I will get a blessing with what is left,

And never miss it.

Your small house, too, in ruin!

Its feeble walls the winds are scattering!

And nothing now, to build a new one,

Of coarse grass green!

And bleak December’s winds coming,

Both bitter and keen!

You saw the fields laid bare and wasted,

And weary winter coming fast,

And cozy here, beneath the blast,

You thought to dwell,

Till crash! the cruel plough passed

Out through your cell.

That small bit heap of leaves and stubble,

Has cost you many a weary nibble!

Now you are turned out, for all your trouble,

Without house or holding,

To endure the winter’s sleety dribble,

And hoar-frost cold.

But little Mouse, you are not alone,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes of mice and men

Go often awry,

And leave us nothing but grief and pain,

For promised joy!

Still you are blessed, compared with me!

The present only touches you:

But oh! I backward cast my eye,

On prospects dreary!

And forward, though I cannot see,

I guess and fear!

January 18, 2024

Book Review: Little Women (and Good Wives)

I like Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. It’s a great classic and in many ways, it is right up my alley: gentle, warm, deep, encouraging, historical, full of three-dimensional characters and relationships, and challenging ideas. It is a little vignette-y for me, but I forgive it because it feels right for the time and it does eventually pay off with some through-story-lines. It also lacks the kind of description I enjoy, but the straight-forward, unobtrusive language helps to usher the reader into the setting, anyhow.

I am fond of reading the classics, if you can’t tell. I’m also fond of reading the new, literary stuff, actually, but old titles weigh more heavily on my conscience because I haven’t read them yet even though they’ve been around for fifty, a hundred, even a thousand years. I have actually read Little Women twice before: first as a tween and then as a young woman with a limited library and no children (therefore some free time). Both these readings happened before The Starving Artist, so I wanted to return to reading Little Women for a review and since it came up on the Christmas reading list, I thought it was time. (FYI, it is not a Christmas book and I wouldn’t recommend it as such. There is only one main scene that takes place on Christmas, though you could read that part at Christmastime…) I remember liking the book before, though I would imagine most modern readers do not read this work outside of a vacuum: with the two popular movie adaptations plus any other number of adaptations. This was me, too. I have seen both the 1994 and 2019 versions more than once each because I like them for themselves. But in every version I had always felt disappointed at the end of the story. Perhaps not anymore? There is a meta sense to this thing that Greta Gerwig (2019) brought attention to and, well, I am also older and see things in the text I didn’t want to see before. It’s a classic and remains a classic and I enjoyed reading it and found so much history, comfort, even wisdom in it.

Jo March is the second-oldest of four sisters in Civil War Massachusetts. Her father is gone to war and her household, with the patient, loving, indomitable Marmee at the helm, is struggling with poverty, courage, compassion, and what it means to come of age in a society skewed toward men’s empowerment and fulfillment. The sisters each have distinct personalities: Meg, the eldest, is sweet and expected, while also being tempted by ribbons and bows and wealth; Jo is tempestuous and ambitious and feels much more at home with the boys and doing “boyish” things; Beth is docile and angelic, a paragon of domesticity; Amy is immature (as the youngest, partly) and girly, determinedly refined and pragmatic. Into the mansion next door moves an isolated young man with his crotchety grandfather. Woven with the friendships, romances, and family vignettes are the struggles of each girl to grow into the “little women” that they hope Father will find when he finally comes home. Meg meets a man. Jo rages against the world. Beth becomes frail. Amy has the grandest plans of all. And always, there is Laurie.

It’s hard to know where to start here, because there is a lot to say about this book. Let’s do this first: this is not actually one novel. Most copies in the United States are sold as just one bound book, titled Little Women, but it’s actually two books in one: Little Women and Good Wives. In my old, battered, Watermill Classics trade paperback, these books are separated with markers that read “Part I” and “Part II.” There is no acknowledgement, really, that there are two books there. But officially, if you make your way through that big ol’ copy of Little Women, you are two books closer to your annual reading goal, not one. Officially, Little Women ends with the shadow of Meg growing up and entering into an understanding with a young man. Good Wives picks up three years later and concentrates on the four sisters (and Laurie) figuring out their lives and entering into partnerships. Together, both these books make the story that we think of (and that the movies portray) with its overarching story of Jo’s and Laurie’s relationship—left hanging in between books—but they are also very distinct. The first is an innocent tale about children full of domestic doings and tough lessons, while the second is full of separation and big choices, increasing the epistolary approach because characters are literally separated for large sections.

And let’s address that I said “its overarching story of Jo’s and Laurie’s relationship.” I did say it. Head on. The biggest problem people have with this book is also intimately tied to the author and her relationship with these books, her world, and her publisher. Is the book about Jo and Laurie, at all? Let’s talk about that, because I think that most people would say, yes, it is, which is why they should have ended up together… but that’s spoiling things! And yet we can’t really talk about this without knowing a main conclusion of the plot. If you want to stop reading the review, fine, but I don’t think knowing the ending will really ruin the charm of the book and it will definitely help you understand how Alcott got to the ending… if she should have gotten where she got… if the ending is really what you think it is when you read it, anyway.

First things first: Little Women (as both books) is considered a work of autobiographical fiction. Yes, Jo is Alcott, though not in every particular. Alcott had three sisters, Anna, Elizabeth, and May. The four sisters shared birth orders and personalities with, respectively, Meg, Beth, and Amy. Their general circumstances and bent as characters (including Marmee and Father) are the same. But after that, things vary. Many of the experiences in Little Women and Good Wives are ones that Alcott had had, but they don’t necessarily happen to the same people or in the same order or whatever. Alcott did, obviously become a writer, but she did not marry, on purpose.

Which leads us to the Greta Gerwig (2019) version of the movie and the ending of the book. Yes, I had always wished Jo and Laurie would have ended up married by the end of the story and felt cheated when I read it as a younger person. However, reading it this time and knowing what I am about to tell you, I saw things that I had refused to see before, namely that the foreshadowing in the book (especially in Little Women) is that Jo will get married but that Amy and Laurie will end up together. I dare you. Go through the book and find references to the future, little hints. There are many that Jo will end up married, despite herself (in speeches by Marmee, Jo’s insistence otherwise, etc.). There are also a handful that Amy and Laurie are destined for one another (like really obvi ones). So there. What opened my eyes to this was an article about Greta Gerwig’s movie version by someone, somewhere (there are a remarkable number of articles about this movie, including at every major magazine) that pointed out Gerwig had not made one ending to her movie, but two. And both were playing before us at the same time. I was like, p-shaw!, because I’d seen the movie and I certainly didn’t remember that. I just remembered that the new version sold me on Bhaer more than any other ever had. So, I went back and watched both movies after re-reading the book(s) again. And sure enough! Gerwing used lighting, music, and tone cues to suggest that after Jo sold her book, the rest of the story was a fabrication made for the publisher and Jo’s “happily ever after” was actually getting published and being an independent woman. And the silly thing is, this actually works. The film remains open-ended, and you can walk away from it with whatever you want.

However, though this be cool and interesting and contemplative, I don’t think it works as a direct reading of the book. Gerwig was trying to blend the autobiographical work with Alcott’s real life, because, well, because there is evidence to suggest that Alcott had written an ending to Good Wives that left Jo unmarried, full stop. Her publisher said no way that won’t sell. Alcott added a cattywampus ending where Amy ends up with Laurie and Jo with some rando guy and now Alcott’s stuck it to the man. And this may be the truth of it (at least that Alcott was fond of sticking it to the man), but I think Alcott was wrong and possibly misleading in this side-story. First of all, as I pointed out, all the fingers of foreshadow actually point toward Jo + some future guy and Amy + Laurie, and this includes in the first book, which had already been published by the time this little debate-tiff was going on. Second, Alcott was used to writing to an audience and had no problem with giving her readership what they wanted. She understood that Jo left as a spinster—at that time, in that place—would read unsatisfactory for the young girls who were so fond of her writing, so I don’t know why she’d suddenly have the right to throw a fit over Jo’s ending. Third, as forward-minded as she was about women’s rights, it was still 1869. Alcott was not a time traveler. She was beholden to the ideas of her time, even in her own head (as we all are). And let’s be honest. Getting married really was a woman’s best bet back then, so most gals might as well dream about a loving, romantic marriage. Alcott threw in the marriage for the meeting of the minds as a pre-feminist bonus. As she also sold a generation on a girl who enjoyed doing boy things and hanging out with boys, a girl who grew to be a woman who remained besties with the same boy as a man. Honestly, marrying Laurie off to a sister was probably the only way to portray this lifelong, cross-gender friendship in the books (or one of few; perhaps he could have become a celibate pastor or found out he was her long-lost brother or something). So what do we get? A story of deep friendship. Between a girl and boy. And, newsflash, that often doesn’t lead to marriage and is a wonderful thing to have in a book for young girls.

In conclusion, if Alcott had ended the book(s) differently than she did, I think it would have been in spite, or to spite her publisher and readers, and that would have been cheating, as a writer. I mean, the woman wrote mostly popular fiction, so what was she trying to prove, exactly? We might be putting a little too much of our own times and attitude into it. The book is fiction, and quite frankly I would have felt unsatisfied without the romances coming together in the end because it was written that way from page one, though my views on which way has changed through the years.

Moving on. Talking to a friend while reading this again, I was surprised by two things. First, this friend has also changed her mind about the romances as she has aged (okay, not the surprising). But more surprisingly, this friend has read and re-read Little Women. I don’t know. Our society is so weird, we have these very my camp-your camp views of people and in real life this just doesn’t play out. Classics like Little Women, in my head, are earmarked for homeschool families and church libraries, but that’s just not at all true. Not only are there some modern ideas in a book like this, but it doesn’t matter—it’s a calm, soothing, historical, classic story full of likeable characters and most people are happy to read something like that, even if there are themes of religion and Christianity throughout. Even secular or atheistic people don’t actually spontaneously combust if they come into contact with Christian characters or ideas, and most readers remain unoffended by the portrayal of wise parents, charitable children, and traditional practice of Victorian-era, Western, Protestant Christianity. For those of you who are antagonistic toward this stuff, be warned: there are many conversations and actions built around a simple, Biblical faith. If you happen to admire this life or can read outside of your own beliefs (how very unmodern of you!), then enjoy a classic without regret.

Which leads me to my last thing to say. I admire the characters and their journeys in Little Women (and the regrettably titled Good Wives). You know what else I admire? The characters and their journeys in Anne of Green Gables and the rest of the series and all of L. M. Montgomery’s work. I actually read the Anne series of books approximately once a year. I was a little alarmed, then, when reading Little Women this time, to find whole scenes that felt, ahem, a little too familiar. Surely, these were coincidences? Or common tropes at the time? Surely, a woman on Prince Edward Island and one in Massachusetts, both in the 1800s, would have the same little stories to tell about people in very similar situations? Like the girl student being “struck” and then studying at home? And a character dressing up in unfamiliar frills to find that it doesn’t suit? Surely Montgomery wasn’t writing early fan fic?! What I couldn’t ignore was that Alcott’s publications had about 40 years on Montgomery’s, and there are some really obvious likenessness. As far as I can tell, Montgomery did site Alcott as an inspiration, and some of these tales might have been universal or even like urban legends. But it gets a little too close for comfort for me now and again. Then again, perhaps I should give Montgomery a little more space: there is nothing new under the sun and I have watched as many books have been published over the past decade that have elements which I have already written and not yet published. That’s just the way good ideas happen: not exclusively. Take what you will from this disturbing observation.

Little Women (and Good Wives) is a classic. I like reading it. I might read it again. Lots of people like reading it. I would bet the vast majority of these people are ladies, but certainly not all. The tales are full of old fashioned ideals, but these are not nearly as controversial as you might think, especially if you are giving it a compassionate reading. There is much to learn from it, though much is made of generalizations. The text also challenges plenty, and Jo is a girl who is questioning her gender if ever I saw one, she just grows up and decides that she’s a woman who relates well with boys and surrounds herself with them, as well as has a man for a bestie—she owns the spectrum and both sides of her personality. There is also much ado about Christianity, not so much the philosophy highlighted in the Gerwig movie. For example, “little women” isn’t used as some sort of limited idea about women being literally or figuratively small, but more like “YA girls.” The story is so warm and moving. There is laughter. There are tears. And in the end, you have two-fer with a twist ending straight out of (fictionalized) history.

Books by Louisa May Alcott:

The Flag of Our UnionA Long Fatal Love ChaseLittle Women (also titled Beth, Jo, Meg and Amy)Good Wives (most often published as the second part to Little Women)Little Men (about Jo’s sons)Jo’s Boys and How They Turned Out (Little Men, part II)Lots of other books and short stories

Some author’s books get all caught up in the story of the author, herself. Such is often the case with a modern reading of Little Women. I have stayed out of Alcott’s hair as much as possible in the review above, but there were some things we needed to know about her. In the end, if you noticed, I wagged my finger at Miss Alcott and told her to get her own business out of the novel, because it has to do what it has to do, despite her. However, Little Women is semiautobiographical, so there’s that. Here’s a quick breeze through the rest of Alcott’s deal.

She was born in Philly in 1832 and moved around like wildfire (30 times) until she was a young woman. Her dad was an educator and a Transcendentalist and her mother a social worker. They were poor and Alcott sought to remedy that for herself. Two neat factoids: they hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, briefly, and Alcott was the first women to vote in Massachusetts in a school board election. Alcott was a proponent of various forward-thinking things, including feminism and civil rights. She had to work instead of go to school, and eventually ended up as a nurse in the Civil War. She grew up around famous people and hobnobbed with the best thinkers and writers of the time. She eventually started getting published and wrote many (anonymous) gothic thrillers and sensation stories. She travelled in Europe. Wrote her semi-autographical books. Never married (though she did have at least one romance). Ended up raising her sister’s daughter after the sister died, until Alcott also died at age 55. Little Women was very popular, but Alcott didn’t like the limelight. She was sickly in her later years. Nowadays, you can visit her body on Author’s Ridge in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, or you can visit the family home, which is now a museum. Alcott is honored not just for her writing, but also as a feminist and suffragette, as well as an abolitionist.

QUOTES

“…while we wait, we may all work…” (p10).

“’I’d given one man, and thought it too much, while he gave four, without grudging them’” (p48).

“…conceit spoils the finest genius …. The consciousness of possessing and using it well should satisfy one, and the great charm of all power is modesty” (p77).

“’My Jo, you may say anything to your mother, for it is my greatest happiness and pride to feel that my girls confide in me, and know how much I love them’” (p89).

“’…I won’t fret, but it does seem as if the more gets the more one wants, doesn’t it?’” (p93).

“’Yes; I wanted you to see how the comfort of all depends on each doing her share dutifully’” (p129).

“Work is wholesome, and there is plenty for everyone; it keeps us from ennui and mischief, is good for heath and spirits, and gives us a sense of power and independence better than money or fashion” (p129).

“Have regular hours for work and play; make each day both useful and pleasant, and prove that you understand the worth of time by employing it well” (p130).

“Jo scribbled away till the last page was filled, when she signed her name with a flourish, and threw down her pen, exclaiming: / ‘There, I’ve done my best! If this won’t suit I shall have to wait till I can do better’” (p162).

“Go on with your work as usual, for work is a blessed solace. Hope and keep busy; and whatever happens, remember that you never can be fatherless’” (p184).

“…love, protection, peace, and health—the real blessings in life” (p201).

“…in the silence, learned the sweet solace with affection administers to sorrow” (p203).

“’Fullness to them a burden is, / That go on pilgrimage; / Here little, and hereafter bliss, / Is best from age to age!” (a hymn from the time, p246).

“…the love of power, which sleeps in the bosoms of the best of little women” (p251).

“The best of us have the spice of perversity in us…” (p252).

“’You can’t live on friends; try it, and see how cool they’ll grow’” (p253).

“’I am satisfied; I’ve done what I undertook, and it’s not my fault that it failed” (p291).

“Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room , put on her scribbling suit, and ‘fall into a vortex,’ as she expressed it, writing away at her novel…” (p292).

“You’ll never look finished if you are not careful about the little details, for they make up the pleasing whole” (p320).

“…so I wait for a chance to confer a great favor, and let the small ones slip; but they tell best in the end, I fancy” (p327).

“…a kiss for a blow is always best, though it’s not very easy to give it sometimes…” (p334).

“…hearts, like flowers, cannot be rudely handled, but must open naturally” (p364).

“…preferred to have her own way first, and beg pardon for it afterward” (p386).

“She began to see that character is a better possession than money, rank, intellect, or beauty” (p391).

“Beth could not reason upon nor explain the faith that gave her courage and patience to give up life, and cheerfully wait for death. Like a confiding child, she asked no questions, but left everything to God and nature …. And clung more closely to dear human love, from which our Father never means us to be weaned, but through which He draws us closer to Himself” (p414).

“That is the secret of our home happiness: he does not let business wean him from the little cares and duties that affect us all, and I try not to let domestic worries destroy my interest in his pursuits” (p434).

“…she recognized the beauty of her sister’s life—uneventful, unambitious, yet full of the genuine virtues which ‘smell sweet, and blossom in the dust,’ the self-forgetfulness that makes the humblest on earth remembered soonest in heaven, the true success which is possible to all” (p462).

“I used to think I couldn’t let you go; but I’m learning to feel that I don’t lose you; that you’ll be more to me than ever, and death can’t part us, though it seems to” (p464).

“…for love is the only thing that we can carry with us when we go and it makes the end so easy” (p464).

“Satan is proverbially fond of providing employment for full and idle hands” (p469).

“She didn’t care to be a queen of society now half so much as she did to be a lovable woman” (p472).

“…marriage, they say, halves one’s rights and doubles one’s duties” (p496).

“If he is old enough to ask the questions he is old enough to receive true answers” (p515).

I immediately (re-)watched the 1994 and 2019 movie versions of Little Women. I have already written about the latter on in the above review. I love both of these movies. The first is a classic period drama that really smacks of the book. The second is a little more challenging to the original work in the spirit of Alcott’s feminism, but the story stays rooted in history. All around, great costumes, great acting (2019’s Amy being a stand-out, I thought, though she looks far too old for the first part), nice scenery and cinematography. And they both reach to make sense of the nontraditional romance. I will always read Beth and see Claire Danes in my head. Once you’ve read the book(s), you’ll want to watch both of these. (There are also half a dozen other adaptations, including some on the BBC which I have heard confuse people into thinking they are supposed to be taking place in England.)

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.com1994 MOVIE

I am not the biggest fan of the more classic movie. For me, the issues in the book carried right over into the movie, and the end stayed just as unsatisfactory as it always had been, though right after reading it I didn’t feel quite as strongly about Jo and Laurie. Also, I don’t like the way Susan Sarandon played Marmee. On the other hand, if you want a gentle, sweet, and sad movie that is pretty decent, then I won’t tell you that this is a bad movie, because it’s not. And there is something about Winona Ryder as Jo. Endearing.

Image from IMDB.com