R. Scott Bakker's Blog, page 11

January 11, 2016

A Secret History of Enlightened Animals (by Ben Cain)

As proud and self-absorbed as most of us are, you’d expect we’d be obsessed with reading history to discover more and more of our past and how we got where we are. But modern historical narratives concentrate on the mere facts of who did what to whom and exactly when and where such dramas played out. What actually happened in our recent and distant past doesn’t seem grandiose enough for us, and so we prefer myths that situate our endeavours in a cosmic or supernatural background. Those myths can be religious, of course, but also secular as in films, novels, and the other arts. We’re so fixated on ourselves and on our cultural assumptions that we must imagine we’re engaged in more than just humdrum family life, business, political chicanery, and wars. We’re heroes in a universal tale of good and evil, gods and monsters. We thereby resort to the imagination, overlooking the existential importance of our actual evolutionary transformation. When animals became people, the universe turned in its grave.

Awakening from Animal Servitude unto Alienation

The so-called wise way of life, that of our species, originates from the birth of an anomalous form of consciousness. That origin has been widely mythologized to protect us from the vertigo of feeling how fine the line is between us and animals. Thus, personal consciousness has been interpreted as an immaterial spirit or as a spark left behind by the intrusion of a higher-dimensional realm into fallen nature, as in Gnosticism, or as an illusion to maintain the play of the slumbering God Brahman, as in some versions of Hinduism, and so on and so forth. But the consciousness that separates people from animals is merely the particular higher-order thought—that is, a thought about thoughts—that you (your lower-order thoughts) are free in the sense of being autonomous, that you’re largely liberated from naturally-selected, animal processes such as hunting for food or seeking mates in the preprogrammed ways. That thought eventually comes to lie in the background of the flurry of mental activity sustained by our oversized brains, along with the frisson of fear that accompanies the revelation that as long as we can think we’re free from nature, we’re actually so. This is because such a higher-order thought, removed as it is from the older, animal parts of our brain, is just what allows us to independently direct our body’s activities. The freedom opened up by human sentience is typically experienced as a falling away from a more secure position. In fact, our collective origin is very likely encapsulated in each child’s development of personhood, fraught as that is with anxiety and sadness as well as with wonder. Children cry and sulk when they don’t get their way, which is when they learn that they stand apart from the world as egos who must strive to live up to otherworldly social standards.

Animals become people by using thought to lever themselves into a black hole-like viewpoint subsisting outside of nature as such. The results are alienation and the existential crisis which are at the root of all our actions. Organic processes are already anomalous and thus virtually miraculous. Personhood represents not progress, since the values that would define such an advance are themselves alien and unnatural by being anthropocentric, but a maximal state of separation from the world, the exclusion of some primates from the environments that would test their genetic mettle. Personal consciousness is the carving of godlike beings from the raw materials of animal slaves, by the realization that thoughts—memories, emotions, imaginings, rational modeling for the sake of problem-solving—comprise an inner world whose contents need not be dictated by stimuli. The cost of personhood, that is, of virtual godhood in the otherwise mostly inanimate universe, is the suffering from alienation that marks our so-called maturity, our fall from childhood innocence whereupon we land in the adult’s clownish struggles with hubris. Our independence empowers us to change ourselves and the world around us, and so we assume we’re the stars of the cosmic show or at least of the narrative of our private life. But because the business of our acting like grownups is witnessed by hardly any audience at all—except in the special case of celebrities who are ironically infantilized by their fame, because the wildly inhuman cosmos is indifferent to our successes and failures—we typically develop into existential mediocrities, not heroes. We overcompensate for the anguish we feel because our thoughts sever us from everything outside our skull, becoming proud of our adult independence; we’re like children begging their parents to admire their finger paintings. The natural world responds with randomness and indiscriminateness, with luck and indifference, humiliating us with a sense of the ultimate futility of our efforts. Our oldest solution is to retreat to the anthropocentric social world in which we can honour our presumed greatness, justly rewarding or punishing each other for our deeds as we feel we deserve.

Hypersocialization and the Existential Crisis of Consciousness

The alienation of higher consciousness is followed, then, by intensive socialization. Animals socialize for natural purposes, whereas we do so in the wake of the miracle of personhood. Our relatively autonomous selves are miraculous not just because they’re so rare (count up the rocks and the minds in the universe, for example, and the former will so outnumber the latter that minds will seem to have spontaneously popped into existence without any general cause), but because whereas animals adapt to nature, conforming to genetic and environmental regularities, people negate those regularities, abandoning their genetic upbringing and reshaping the global landscape. The earliest people channeled their resentment against the world they discovered they’re not wholly at home in, by inventing tools to help them best nature and its animal slaves, but also by forming tribes defined by more and more elaborate social conventions. The more arbitrary the implicit and explicit laws that regulate a society, the more frenzied its members’ dread of being embedded in a greater, uncaring wilderness. Again, human societies are animalistic in so far as they rely on the structure of dominance hierarchies, but whereas alpha males in animal groups overpower their inferiors for the natural reason of maintaining group cohesion to protect the alphas whose superior genes are the species’ best hope for future generations, human leaders adopt the pathologies of the God complex. Indeed, all people would act like gods if only they could sustain the farce. Alas, just as every winning lottery ticket necessitates multitudes of losers, every full-blown personal deity depends on an army of worshippers. Personhood makes us all metaphysically godlike with respect to our autonomy and our liberation from some natural, impersonal systems, but only a lucky minority can live like mythical gods on Earth.

We socialize, then, to flatter our potential for godhood, by elevating some of our members to a social position in which they can tantalize us with their extravagant lifestyles and superhuman responsibilities. We form sheltered communities in which we can hide from nature’s alien glare. Our elders, tyrants, kings, and emperors lord it over us and we thank them for it, since their appallingly decadent lives nevertheless prove that personhood can be completed, that an absolute fall from the grace of animal innocence isn’t asymptotic, that our evolution has a finite end in transhumanity. Our psychopathic rulers are living proofs that nature isn’t omnipresent, that escape is possible in the form of insanity sustained by mass hallucination. We daydream the differences between right and wrong, honour and dishonour, meaning and meaninglessness. We fill the air with subtle noises and imagine that those symbols are meant to lay bare the final truth. We thus mitigate the removal of our mind from the world, with a myth of reconciliation between thoughts and facts. But language was likely conceived of in the first place as a magical instrument, that is, as an extension of mentality into nature which was everywhere anthropomorphized. Human tribes were assumed to be mere inner circles within a vast society of gods, monsters, and other living forces. We socialized, then, not just to escape to friendly domains to preserve our dignity as unnatural wonders, but to pretend that we hadn’t emerged just by a satanic/promethean act of cognitive defiance, with the ego-making thought that severs us from natural reality. We childishly presumed that the whole universe is a stage populated by puppets and actors; thus, no existential retreat might have been deemed necessary, because nature’s alienness was blotted out in our mythopoeic imagination. As in Genesis, God created by speaking the world into being, just as shamans and magicians were believed to cast magical spells that bent reality to their will.

But every theistic posit was part of an unconscious strategy to avoid facing the obvious fact that since all gods are people, we’re evidently the only gods. Nevertheless, having conceived of theistic fictions, we drew up models to standardize the behaviour of actual gods. Thus, the Pharaoh had to be as remote and majestic as Osiris, while the Roman Emperor had to rule like Jupiter, the Raj had to adjudicate like Krishna, the Pope had to appear Christ-like, and the U.S. President has to seem to govern like your favourite Hollywood hero. The double standard that exempts the upper classes from the laws that oppress the lowly masses is supposed to prevent an outbreak of consciousness-induced angst. Social exceptions for the upper class work with mass personifications and enchantments of nature, and those propagandistic myths are then made plausible by the fact that superhuman power elites actually exist. Ironically, such class divisions and their concomitant theologies exacerbate the existential predicament by placing those exquisite symbols of our transcendence (the power elites) before public consciousness, reminding us that just as the gods are prior to and thus independent of nature, so too we who are the only potential or actual gods don’t belong within that latter world.

Scientific Objectivity and Artificialization

Hypersocialization isn’t our only existential stratagem; there’s also artificialization as a defense against full consciousness of our unnatural self-control. Whereas the socializer tries to act like a god by climbing social ladders, bullying his underlings, spending unseemly wealth in generational projects of self-aggrandizement, and creating and destroying societal frameworks, the artificializer wants to replace all of nature with artifacts. That way, what began as the imaginary negation of nature’s inhuman indifference to life, in the mythopoeic childhood of our species, can be fulfilled when that indifference is literally undone by our re-engineering of natural processes.

To do that, the artificializer needs to think, not just to act, like a god. That required forming cognitive programs that don’t depend on the innate, naturally-selected ones. Cognitive scientists maintain that the brain’s ability to process sensations, for example, evolved not to present us with the absolute truth but to ensure our fitness to our environment, by helping us survive long enough to sexually reproduce. Animal neural pathways differ from personal ones in that the former serve the species, not the individual, and so the animal is fundamentally a puppet acting out its life cycle as directed by its genetic programming and by certain environmental constraints. Animals can learn to adapt their behaviour to their environment and so their behaviour isn’t always robotic, but unless they can apply their learning towards unnatural ends, such as by developing birth control techniques that systematically thwart the pseudo goals of natural selection, they’ll think as animals, not as gods. Animals as such are entirely natural creatures, meaning that in so far as their behaviour is mediated by an independent control center, their thinking nevertheless is dedicated to furthering the end of natural selection, which is just that of transmitting genes to future generations. By contrast, gods don’t merely survive or even thrive. Insects and bacteria thrive, as did the dinosaurs for millions of years, but none were godlike because none were existentially transformed by conscious enlightenment, by a cognitive black hole into which an animal can fall, creating the world of inner space.

People, too, have animal programming, such as the autonomic programs for processing sensory information. Social behaviour is likewise often purely animalistic, as in the cases of sex and the power struggle for some advantage in a dominance hierarchy. Rational thinking is less so and thus less natural, meaning more anti-natural in that it serves rational ideals rather than just lower-order aims. To be sure, Machiavellian reasoning is animalistic, but reason has also taken on an unnatural function. Whereas writing was first used for the utilitarian purpose of record keeping, reason in the Western tradition was initially not so practical. The Presocratics argued about metaphysical substances and other philosophical matters, indicating that they’d been largely liberated from animal concerns of day-to-day survival and were exploring cognitive territory that’s useful only from the internal, personal perspective. Who am I really? What is the world, ultimately speaking? Is there a worthy difference between right and wrong? Such philosophical questions are impossible without rational ideals of skepticism, intellectual integrity, and love of knowledge even if that knowledge should be subversive—as it proved to be in Socrates’ classic case.

While the biblical Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son for the sake of hypersocializing with an imaginary deity, Socrates died for the antisocial quest of pursuing objective knowledge that inevitably threatens the natural order along with the animal social structures that entrench that order, such as the Athenian government of his day. Socrates cared not about face-saving opinions, but about epistemic principles that arm us with rationally-justified beliefs about how the world might be in reality. Much later, in the Scientific Revolution, rationalists (which is to say philosophers) in Europe would revive the ancient pagan ideal of reasoning regardless of the impact on faith-based dogmas. Scientists like Isaac Newton developed cognitive methods that were counterintuitive in that they went against the grain of more natural human thinking that’s prone to fallacies and survival-based biases. In addition, he served rational institutions, namely the Royal Society and Cambridge, which rivaled the genes for control over the enlightened individual’s loyalty. Moreover, the findings of those cognitive methods were symbolized using artificial languages such as mathematics and formal logic, which enabled liberated minds to communicate their discoveries without the genetic tragicomedies of territorialism, fight-or-flight responses, hero worship, demagoguery, and the like that are liable to be triggered by rhetoric and metaphors expressed in natural languages.

But what is objective knowledge? Are scientists and other so-called enlightened rationalists as neutral as the indifferent world they study? No, rationalists in this broad sense are partly liberated from animal life but they’re not lost in a limbo; rather, they participate in another, unnatural process which I’m calling artificialization. Objectivity isn’t a purely mechanical, impersonal capacity; indeed, natural processes themselves have aesthetically interpretable ends and effective means, so there are no such capacities. In any case, the search for objective knowledge builds on human animalism and on our so-called enlightenment, on our having transcended our animal past and instincts. We were once wholly slaves to nature and we often behave as if we were still playthings of natural forces. But consciousness and hypersocialization provided escapes, albeit into fantasy worlds that nevertheless empowered us. We saw ourselves as being special because we became aware of the increasing independence of our mental models from the modeled territory, owing to the formers’ ultra-complexity. The inner world of the mind emerged and detached from the natural order—not just metaphysically or abstractly, but psychologically and historically. That liberation was traumatic and so we fled to the fictitious world of our imagination, to a world we could control, and we pretended the outer world was likewise held captive to our mental projections. The rational enterprise is fundamentally another form of escape, a means of living with the burden of hyper-awareness. Instead of settling for cheap, flimsy mental constructions such as our gods, boogeymen, and the panoply of delusions to which we’re prone, and instead of hording divinity in the upper social classes that exercise their superpowers in petty or sadistic projects of self-aggrandizement, we saw that we could usurp God’s ability to create real worlds, as it were. We could democratize divinity, replacing impersonal nature with artificial constructs that would actually exist outside our minds as opposed to being mere projections of imagination and existential longing.

The pragmatic aspect of objectivity is apparent from the familiar historical connections between science, European imperialism, and modern industries. But it’s apparent also from the analytical structure of scientific explanations itself. The existential point of scientific objectivity was paradoxically to achieve a total divorce from our animal side by de-personalizing ourselves, by restraining our desire for instant gratification, scolding our inner child and its playpen, the imagination, and identifying with rational methods. Whereas an animal relies on its hardwired programs or on learned rules-of-thumb for interpreting its environment, an enlightened person codifies and reifies such rules, suspending disbelief and siding with idealized or instrumental formulations of these rules so that the person can occupy a higher cognitive plane. Once removed from natural processes by this identification with rational procedures and institutions, with teleological algorithms, artificial symbols and the like, the animal has become a person with a godlike view from outside of nature—albeit not an overview of what the universe really is, but an engineer’s perspective of how the universe works mechanically from the ground up.

To see what I mean, consider the Hindu parable of the blind men who try to ascertain the nature of an elephant by touching its different body parts. One of the men feels a tusk and infers that the elephant is like a pipe. Another touches the leg and thinks the whole animal is like a tree trunk. Another touches the belly and believes the animal is like a wall. Another touches the tail and says the elephant is like a rope. Finally, another one touches the ear and thinks the elephant is like a hand fan. One of the traditional lessons of this parable is that we can fallaciously overgeneralize and mistake the part for the whole, but this isn’t my point about science. Still, there is a difference between what the universe is in reality, which is what it is in its entirety in so far as all of its parts form a cohesive order, and how inquisitive primates choose to understand the universe with their divisive concepts and models. Scientists can’t possibly understand everything in nature all at once; the word “universe” is a mere placeholder with no content adequate to the task of representing everything that’s out there interacting to produce what we think of as distinct events. We have no name for the universe which gives us power over it by identifying its essence, as it were. So scientists analyze the whole, observing how parts of the world work in isolation, ideally in a laboratory. They then generalize their findings, positing a natural regularity or nomic relation between those fragments, as pictured by their model or theory. It’s as if scientists were the blind men who lack the brainpower to cognize the whole of natural reality, and so they study each part, perhaps hoping that if they cooperate they can combine their partial understandings and arrive at some inkling of what the natural universe in general is. Unfortunately, the deeper we look into nature, the more complexity we find in its parts and so the more futile becomes any such plan for total comprehension. Scientists can barely keep up with advances in their subfields; the notion that anyone could master all the sciences as they currently stand is ludicrous, and there’s still much in the world that isn’t scientifically understood by anyone.

So whatever the scientist’s aspiration might be, the effect of science isn’t the achievement of complete, final understanding of everything in the universe or of the whole of nature. Instead, science allows us to rebuild the whole based on partial, analytical knowledge of how the world works. Suppose scientists discover an extraterrestrial artifact and they have no clue as to the artifact’s function, which is to say they have no understanding of what the object is in reality. Still, they can reverse-engineer the artifact, taking it apart, identifying the materials used to assemble it and certain patterns in how the parts interact with each other. With that limited knowledge of the artifact’s mechanical aspect, scientists might be able to build a replica or else they could apply that knowledge to create something more useful to them, that is, something that works in similar ways to the original but which works towards an end supplied by the scientists’ interests, not the alien’s. There would be no point in replicating the alien technology, since the artifact would be useless without knowledge of what it’s for or without even a shared interest in pursuing that alien goal. Replace the alien artifact with the natural universe and you have some measure of the Baconian position of human science. Of course, nature has no designer; nevertheless, we experience natural processes as having ends and so we’re faced with the choice of whether to apply our piecemeal knowledge of natural mechanisms to the task of reinforcing those ends or to that of adjusting or even reversing them. The choice is to act as stewards of God’s garden, as it were, or as promethean rebels who seek to be divine creators. There are still enclaves of native tribes living as retro-human animals and preserving nature rather than demolishing the wilderness and establishing in its place a technological wonderland built with knowledge of natural mechanisms. But the billions of participants in the science-driven, global monoculture have evidently chosen the promethean, quasi-satanic path.

Existentialism and our Hidden History

History is a narrative that often informs us indirectly about the present state of human affairs, by representing part of our past. Ancient historical narratives were more mythical than fact-based. The New Testament, for example, uses historical details to form an exoteric shell around the Gnostic, transhumanist suspicion that human nature is “fallen” to the extent that we surrender our capacity to transcend the animal life cycle; we must “die” to our natural bodies and be reborn in a glorious, unnatural or “spiritual” form. At any rate, like poetry, the mythical language of such ancient historical narratives is open to endless interpretations, which is to say that such stories are obscure. Josephus’s ancient histories of the Jewish people, written for a Roman audience, aren’t so mythologized but they’re no less propagandistic. By contrast, modern historians strive to avoid the pitfalls of writing highly subjective or biased narratives, and so they seek to analyze and interpret just the facts dug up by archeologists and textual critics. Modern histories are thus influenced by the exoteric presumption about science, which is that science isn’t primarily in the business of artificializing everything that’s wild in the sense of being out of our control, but is just a mode of inquiry for arriving at the objective truth (come what may).

Left out of this development of the telling of history is the existential significance of our evolutionary transition from being animals, which were at one with nature, to being people who are implicitly if not consciously at war with everything nonhuman. What I’ve sketched above is part of our secret history; it’s the story of what it means to be human, which underlies all our endeavours. The significance of our standing between animalism and godhood is hidden and largely unknown or forgotten, because at the root of this purpose that drives us is the trauma of godlike consciousness which we’d rather not relive. We each have our fill of that trauma in our passage from childhood innocence, which approximates the animal state of unknowing, to adult independence. Teen angst, which cultures combat with initiation rituals to distract the teenager with sanctioned, typically delusional pastimes, is the tip of the iceberg of pain that awaits anyone who recognizes the plight entailed by our very form of existence.

In Escape from Freedom, Erich Fromm argued that citizens of modern democracies are in danger of preferring the comfort of a totalitarian system, to escape the ennui and dehumanization generated by modern societies. In particular, capitalistic exploitation of the worker class and the need to assimilate to an environment run more and more by automated, inhuman machines are supposed to drive civilized persons to savage, authoritarian regimes. At least, this was Fromm’s explanation of the Nazis’ rise to power. A similar analysis could apply to the present degeneration of the Republican Party in the U.S. and to the militant jihadist movement in the Middle East. But Fromm’s analysis is limited. To be sure, capitalism and technology have their drawbacks and these may even contribute to totalitarianism’s appeal, as Fromm shows. But this overlooks what liberal, science-driven societies and savage, totalitarian societies have in common. Both are flights from existential reckoning, as I’ve explained: the one revolves around artificialization (Enlightenment, rationalist values of individual autonomy, which deteriorate until we’re left with the fraud of consumerism), the other around hypersocialization (cult of personality, restoring the sadomasochistic interplay between mythical gods and their worshippers). Fromm ignores the existential effect of the rational enlightenment that brought on modern science, democracy, and capitalism in the first place, the effect being our deification. By deifying ourselves, we prevent our treasured religions from being fiascos and we spare ourselves the horror of living in an inhuman wilderness from which we’re alienated by our hyper-awareness.

We created the modern world to accelerate the rate at which nature is removed from our presence. Contrary to optimists like Steven Pinker, modernity hasn’t fulfilled its promise of democratizing divinity, as I’d put it. Robber barons and more parasitic oligarchs do indeed resort to the older departure of hypersocialization, acting like decadent gods in relation to human slaves instead of focusing their divine creativity on our common enemy, the monstrous wilderness. The internet that trivializes everything it touches and the omnipresence of our high-tech gadgets do infantilize us, turning us into cattle-like consumers instead of unleashing our creativity and training us to be the indomitable warriors that alone could endure the promethean mission. This is because we, being the only gods that exist, are woefully unprepared for our responsibility, having retained our animal heritage in the form of our bodies which infect most of our decisions with natural fears and prejudices. At any rate, the deeper story of the animal that becomes a godlike person to obliterate the source of alienation that’s the curse of any flawed, lonely godling helps explain why we now settle more often for the minor anxieties of living in modern civilization, to avoid the major angst of recognizing the existential importance of what we are.

Science, Hypersocialization, and our Secret History (by Ben Cain)

As proud and self-absorbed as most of us are, you’d expect we’d be obsessed with reading history to discover more and more of our past and how we got where we are. But modern historical narratives concentrate on the mere facts of who did what to whom and exactly when and where such dramas played out. What actually happened in our recent and distant past doesn’t seem grandiose enough for us, and so we prefer myths that situate our endeavours in a cosmic or supernatural background. Those myths can be religious, of course, but also secular as in films, novels, and the other arts. We’re so fixated on ourselves and on our cultural assumptions that we must imagine we’re engaged in more than just humdrum family life, business, political chicanery, and wars. We’re heroes in a universal tale of good and evil, gods and monsters. We thereby resort to the imagination, overlooking the existential importance of our actual evolutionary transformation. When animals became people, the universe turned in its grave.

Awakening from Animal Servitude unto Alienation

The so-called wise way of life, that of our species, originates from the birth of an anomalous form of consciousness. That origin has been widely mythologized to protect us from the vertigo of feeling how fine the line is between us and animals. Thus, personal consciousness has been interpreted as an immaterial spirit or as a spark left behind by the intrusion of a higher-dimensional realm into fallen nature, as in Gnosticism, or as an illusion to maintain the play of the slumbering God Brahman, as in some versions of Hinduism, and so on and so forth. But the consciousness that separates people from animals is merely the particular higher-order thought—that is, a thought about thoughts—that you (your lower-order thoughts) are free in the sense of being autonomous, that you’re largely liberated from naturally-selected, animal processes such as hunting for food or seeking mates in the preprogrammed ways. That thought eventually comes to lie in the background of the flurry of mental activity sustained by our oversized brains, along with the frisson of fear that accompanies the revelation that as long as we can think we’re free from nature, we’re actually so. This is because such a higher-order thought, removed as it is from the older, animal parts of our brain, is just what allows us to independently direct our body’s activities. The freedom opened up by human sentience is typically experienced as a falling away from a more secure position. In fact, our collective origin is very likely encapsulated in each child’s development of personhood, fraught as that is with anxiety and sadness as well as with wonder. Children cry and sulk when they don’t get their way, which is when they learn that they stand apart from the world as egos who must strive to live up to otherworldly social standards.

Animals become people by using thought to lever themselves into a black hole-like viewpoint subsisting outside of nature as such. The results are alienation and the existential crisis which are at the root of all our actions. Organic processes are already anomalous and thus virtually miraculous. Personhood represents not progress, since the values that would define such an advance are themselves alien and unnatural by being anthropocentric, but a maximal state of separation from the world, the exclusion of some primates from the environments that would test their genetic mettle. Personal consciousness is the carving of godlike beings from the raw materials of animal slaves, by the realization that thoughts—memories, emotions, imaginings, rational modeling for the sake of problem-solving—comprise an inner world whose contents need not be dictated by stimuli. The cost of personhood, that is, of virtual godhood in the otherwise mostly inanimate universe, is the suffering from alienation that marks our so-called maturity, our fall from childhood innocence whereupon we land in the adult’s clownish struggles with hubris. Our independence empowers us to change ourselves and the world around us, and so we assume we’re the stars of the cosmic show or at least of the narrative of our private life. But because the business of our acting like grownups is witnessed by hardly any audience at all—except in the special case of celebrities who are ironically infantilized by their fame, because the wildly inhuman cosmos is indifferent to our successes and failures—we typically develop into existential mediocrities, not heroes. We overcompensate for the anguish we feel because our thoughts sever us from everything outside our skull, becoming proud of our adult independence; we’re like children begging their parents to admire their finger paintings. The natural world responds with randomness and indiscriminateness, with luck and indifference, humiliating us with a sense of the ultimate futility of our efforts. Our oldest solution is to retreat to the anthropocentric social world in which we can honour our presumed greatness, justly rewarding or punishing each other for our deeds as we feel we deserve.

Hypersocialization and the Existential Crisis of Consciousness

The alienation of higher consciousness is followed, then, by intensive socialization. Animals socialize for natural purposes, whereas we do so in the wake of the miracle of personhood. Our relatively autonomous selves are miraculous not just because they’re so rare (count up the rocks and the minds in the universe, for example, and the former will so outnumber the latter that minds will seem to have spontaneously popped into existence without any general cause), but because whereas animals adapt to nature, conforming to genetic and environmental regularities, people negate those regularities, abandoning their genetic upbringing and reshaping the global landscape. The earliest people channeled their resentment against the world they discovered they’re not wholly at home in, by inventing tools to help them best nature and its animal slaves, but also by forming tribes defined by more and more elaborate social conventions. The more arbitrary the implicit and explicit laws that regulate a society, the more frenzied its members’ dread of being embedded in a greater, uncaring wilderness. Again, human societies are animalistic in so far as they rely on the structure of dominance hierarchies, but whereas alpha males in animal groups overpower their inferiors for the natural reason of maintaining group cohesion to protect the alphas whose superior genes are the species’ best hope for future generations, human leaders adopt the pathologies of the God complex. Indeed, all people would act like gods if only they could sustain the farce. Alas, just as every winning lottery ticket necessitates multitudes of losers, every full-blown personal deity depends on an army of worshippers. Personhood makes us all metaphysically godlike with respect to our autonomy and our liberation from some natural, impersonal systems, but only a lucky minority can live like mythical gods on Earth.

We socialize, then, to flatter our potential for godhood, by elevating some of our members to a social position in which they can tantalize us with their extravagant lifestyles and superhuman responsibilities. We form sheltered communities in which we can hide from nature’s alien glare. Our elders, tyrants, kings, and emperors lord it over us and we thank them for it, since their appallingly decadent lives nevertheless prove that personhood can be completed, that an absolute fall from the grace of animal innocence isn’t asymptotic, that our evolution has a finite end in transhumanity. Our psychopathic rulers are living proofs that nature isn’t omnipresent, that escape is possible in the form of insanity sustained by mass hallucination. We daydream the differences between right and wrong, honour and dishonour, meaning and meaninglessness. We fill the air with subtle noises and imagine that those symbols are meant to lay bare the final truth. We thus mitigate the removal of our mind from the world, with a myth of reconciliation between thoughts and facts. But language was likely conceived of in the first place as a magical instrument, that is, as an extension of mentality into nature which was everywhere anthropomorphized. Human tribes were assumed to be mere inner circles within a vast society of gods, monsters, and other living forces. We socialized, then, not just to escape to friendly domains to preserve our dignity as unnatural wonders, but to pretend that we hadn’t emerged just by a satanic/promethean act of cognitive defiance, with the ego-making thought that severs us from natural reality. We childishly presumed that the whole universe is a stage populated by puppets and actors; thus, no existential retreat might have been deemed necessary, because nature’s alienness was blotted out in our mythopoeic imagination. As in Genesis, God created by speaking the world into being, just as shamans and magicians were believed to cast magical spells that bent reality to their will.

But every theistic posit was part of an unconscious strategy to avoid facing the obvious fact that since all gods are people, we’re evidently the only gods. Nevertheless, having conceived of theistic fictions, we drew up models to standardize the behaviour of actual gods. Thus, the Pharaoh had to be as remote and majestic as Osiris, while the Roman Emperor had to rule like Jupiter, the Raj had to adjudicate like Krishna, the Pope had to appear Christ-like, and the U.S. President has to seem to govern like your favourite Hollywood hero. The double standard that exempts the upper classes from the laws that oppress the lowly masses is supposed to prevent an outbreak of consciousness-induced angst. Social exceptions for the upper class work with mass personifications and enchantments of nature, and those propagandistic myths are then made plausible by the fact that superhuman power elites actually exist. Ironically, such class divisions and their concomitant theologies exacerbate the existential predicament by placing those exquisite symbols of our transcendence (the power elites) before public consciousness, reminding us that just as the gods are prior to and thus independent of nature, so too we who are the only potential or actual gods don’t belong within that latter world.

Scientific Objectivity and Artificialization

Hypersocialization isn’t our only existential stratagem; there’s also artificialization as a defense against full consciousness of our unnatural self-control. Whereas the socializer tries to act like a god by climbing social ladders, bullying his underlings, spending unseemly wealth in generational projects of self-aggrandizement, and creating and destroying societal frameworks, the artificializer wants to replace all of nature with artifacts. That way, what began as the imaginary negation of nature’s inhuman indifference to life, in the mythopoeic childhood of our species, can be fulfilled when that indifference is literally undone by our re-engineering of natural processes.

To do that, the artificializer needs to think, not just to act, like a god. That required forming cognitive programs that don’t depend on the innate, naturally-selected ones. Cognitive scientists maintain that the brain’s ability to process sensations, for example, evolved not to present us with the absolute truth but to ensure our fitness to our environment, by helping us survive long enough to sexually reproduce. Animal neural pathways differ from personal ones in that the former serve the species, not the individual, and so the animal is fundamentally a puppet acting out its life cycle as directed by its genetic programming and by certain environmental constraints. Animals can learn to adapt their behaviour to their environment and so their behaviour isn’t always robotic, but unless they can apply their learning towards unnatural ends, such as by developing birth control techniques that systematically thwart the pseudo goals of natural selection, they’ll think as animals, not as gods. Animals as such are entirely natural creatures, meaning that in so far as their behaviour is mediated by an independent control center, their thinking nevertheless is dedicated to furthering the end of natural selection, which is just that of transmitting genes to future generations. By contrast, gods don’t merely survive or even thrive. Insects and bacteria thrive, as did the dinosaurs for millions of years, but none were godlike because none were existentially transformed by conscious enlightenment, by a cognitive black hole into which an animal can fall, creating the world of inner space.

People, too, have animal programming, such as the autonomic programs for processing sensory information. Social behaviour is likewise often purely animalistic, as in the cases of sex and the power struggle for some advantage in a dominance hierarchy. Rational thinking is less so and thus less natural, meaning more anti-natural in that it serves rational ideals rather than just lower-order aims. To be sure, Machiavellian reasoning is animalistic, but reason has also taken on an unnatural function. Whereas writing was first used for the utilitarian purpose of record keeping, reason in the Western tradition was initially not so practical. The Presocratics argued about metaphysical substances and other philosophical matters, indicating that they’d been largely liberated from animal concerns of day-to-day survival and were exploring cognitive territory that’s useful only from the internal, personal perspective. Who am I really? What is the world, ultimately speaking? Is there a worthy difference between right and wrong? Such philosophical questions are impossible without rational ideals of skepticism, intellectual integrity, and love of knowledge even if that knowledge should be subversive—as it proved to be in Socrates’ classic case.

While the biblical Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son for the sake of hypersocializing with an imaginary deity, Socrates died for the antisocial quest of pursuing objective knowledge that inevitably threatens the natural order along with the animal social structures that entrench that order, such as the Athenian government of his day. Socrates cared not about face-saving opinions, but about epistemic principles that arm us with rationally-justified beliefs about how the world might be in reality. Much later, in the Scientific Revolution, rationalists (which is to say philosophers) in Europe would revive the ancient pagan ideal of reasoning regardless of the impact on faith-based dogmas. Scientists like Isaac Newton developed cognitive methods that were counterintuitive in that they went against the grain of more natural human thinking that’s prone to fallacies and survival-based biases. In addition, he served rational institutions, namely the Royal Society and Cambridge, which rivaled the genes for control over the enlightened individual’s loyalty. Moreover, the findings of those cognitive methods were symbolized using artificial languages such as mathematics and formal logic, which enabled liberated minds to communicate their discoveries without the genetic tragicomedies of territorialism, fight-or-flight responses, hero worship, demagoguery, and the like that are liable to be triggered by rhetoric and metaphors expressed in natural languages.

But what is objective knowledge? Are scientists and other so-called enlightened rationalists as neutral as the indifferent world they study? No, rationalists in this broad sense are partly liberated from animal life but they’re not lost in a limbo; rather, they participate in another, unnatural process which I’m calling artificialization. Objectivity isn’t a purely mechanical, impersonal capacity; indeed, natural processes themselves have aesthetically interpretable ends and effective means, so there are no such capacities. In any case, the search for objective knowledge builds on human animalism and on our so-called enlightenment, on our having transcended our animal past and instincts. We were once wholly slaves to nature and we often behave as if we were still playthings of natural forces. But consciousness and hypersocialization provided escapes, albeit into fantasy worlds that nevertheless empowered us. We saw ourselves as being special because we became aware of the increasing independence of our mental models from the modeled territory, owing to the formers’ ultra-complexity. The inner world of the mind emerged and detached from the natural order—not just metaphysically or abstractly, but psychologically and historically. That liberation was traumatic and so we fled to the fictitious world of our imagination, to a world we could control, and we pretended the outer world was likewise held captive to our mental projections. The rational enterprise is fundamentally another form of escape, a means of living with the burden of hyper-awareness. Instead of settling for cheap, flimsy mental constructions such as our gods, boogeymen, and the panoply of delusions to which we’re prone, and instead of hording divinity in the upper social classes that exercise their superpowers in petty or sadistic projects of self-aggrandizement, we saw that we could usurp God’s ability to create real worlds, as it were. We could democratize divinity, replacing impersonal nature with artificial constructs that would actually exist outside our minds as opposed to being mere projections of imagination and existential longing.

The pragmatic aspect of objectivity is apparent from the familiar historical connections between science, European imperialism, and modern industries. But it’s apparent also from the analytical structure of scientific explanations itself. The existential point of scientific objectivity was paradoxically to achieve a total divorce from our animal side by de-personalizing ourselves, by restraining our desire for instant gratification, scolding our inner child and its playpen, the imagination, and identifying with rational methods. Whereas an animal relies on its hardwired programs or on learned rules-of-thumb for interpreting its environment, an enlightened person codifies and reifies such rules, suspending disbelief and siding with idealized or instrumental formulations of these rules so that the person can occupy a higher cognitive plane. Once removed from natural processes by this identification with rational procedures and institutions, with teleological algorithms, artificial symbols and the like, the animal has become a person with a godlike view from outside of nature—albeit not an overview of what the universe really is, but an engineer’s perspective of how the universe works mechanically from the ground up.

To see what I mean, consider the Hindu parable of the blind men who try to ascertain the nature of an elephant by touching its different body parts. One of the men feels a tusk and infers that the elephant is like a pipe. Another touches the leg and thinks the whole animal is like a tree trunk. Another touches the belly and believes the animal is like a wall. Another touches the tail and says the elephant is like a rope. Finally, another one touches the ear and thinks the elephant is like a hand fan. One of the traditional lessons of this parable is that we can fallaciously overgeneralize and mistake the part for the whole, but this isn’t my point about science. Still, there is a difference between what the universe is in reality, which is what it is in its entirety in so far as all of its parts form a cohesive order, and how inquisitive primates choose to understand the universe with their divisive concepts and models. Scientists can’t possibly understand everything in nature all at once; the word “universe” is a mere placeholder with no content adequate to the task of representing everything that’s out there interacting to produce what we think of as distinct events. We have no name for the universe which gives us power over it by identifying its essence, as it were. So scientists analyze the whole, observing how parts of the world work in isolation, ideally in a laboratory. They then generalize their findings, positing a natural regularity or nomic relation between those fragments, as pictured by their model or theory. It’s as if scientists were the blind men who lack the brainpower to cognize the whole of natural reality, and so they study each part, perhaps hoping that if they cooperate they can combine their partial understandings and arrive at some inkling of what the natural universe in general is. Unfortunately, the deeper we look into nature, the more complexity we find in its parts and so the more futile becomes any such plan for total comprehension. Scientists can barely keep up with advances in their subfields; the notion that anyone could master all the sciences as they currently stand is ludicrous, and there’s still much in the world that isn’t scientifically understood by anyone.

So whatever the scientist’s aspiration might be, the effect of science isn’t the achievement of complete, final understanding of everything in the universe or of the whole of nature. Instead, science allows us to rebuild the whole based on partial, analytical knowledge of how the world works. Suppose scientists discover an extraterrestrial artifact and they have no clue as to the artifact’s function, which is to say they have no understanding of what the object is in reality. Still, they can reverse-engineer the artifact, taking it apart, identifying the materials used to assemble it and certain patterns in how the parts interact with each other. With that limited knowledge of the artifact’s mechanical aspect, scientists might be able to build a replica or else they could apply that knowledge to create something more useful to them, that is, something that works in similar ways to the original but which works towards an end supplied by the scientists’ interests, not the alien’s. There would be no point in replicating the alien technology, since the artifact would be useless without knowledge of what it’s for or without even a shared interest in pursuing that alien goal. Replace the alien artifact with the natural universe and you have some measure of the Baconian position of human science. Of course, nature has no designer; nevertheless, we experience natural processes as having ends and so we’re faced with the choice of whether to apply our piecemeal knowledge of natural mechanisms to the task of reinforcing those ends or to that of adjusting or even reversing them. The choice is to act as stewards of God’s garden, as it were, or as promethean rebels who seek to be divine creators. There are still enclaves of native tribes living as retro-human animals and preserving nature rather than demolishing the wilderness and establishing in its place a technological wonderland built with knowledge of natural mechanisms. But the billions of participants in the science-driven, global monoculture have evidently chosen the promethean, quasi-satanic path.

Existentialism and our Hidden History

History is a narrative that often informs us indirectly about the present state of human affairs, by representing part of our past. Ancient historical narratives were more mythical than fact-based. The New Testament, for example, uses historical details to form an exoteric shell around the Gnostic, transhumanist suspicion that human nature is “fallen” to the extent that we surrender our capacity to transcend the animal life cycle; we must “die” to our natural bodies and be reborn in a glorious, unnatural or “spiritual” form. At any rate, like poetry, the mythical language of such ancient historical narratives is open to endless interpretations, which is to say that such stories are obscure. Josephus’s ancient histories of the Jewish people, written for a Roman audience, aren’t so mythologized but they’re no less propagandistic. By contrast, modern historians strive to avoid the pitfalls of writing highly subjective or biased narratives, and so they seek to analyze and interpret just the facts dug up by archeologists and textual critics. Modern histories are thus influenced by the exoteric presumption about science, which is that science isn’t primarily in the business of artificializing everything that’s wild in the sense of being out of our control, but is just a mode of inquiry for arriving at the objective truth (come what may).

Left out of this development of the telling of history is the existential significance of our evolutionary transition from being animals, which were at one with nature, to being people who are implicitly if not consciously at war with everything nonhuman. What I’ve sketched above is part of our secret history; it’s the story of what it means to be human, which underlies all our endeavours. The significance of our standing between animalism and godhood is hidden and largely unknown or forgotten, because at the root of this purpose that drives us is the trauma of godlike consciousness which we’d rather not relive. We each have our fill of that trauma in our passage from childhood innocence, which approximates the animal state of unknowing, to adult independence. Teen angst, which cultures combat with initiation rituals to distract the teenager with sanctioned, typically delusional pastimes, is the tip of the iceberg of pain that awaits anyone who recognizes the plight entailed by our very form of existence.

In Escape from Freedom, Erich Fromm argued that citizens of modern democracies are in danger of preferring the comfort of a totalitarian system, to escape the ennui and dehumanization generated by modern societies. In particular, capitalistic exploitation of the worker class and the need to assimilate to an environment run more and more by automated, inhuman machines are supposed to drive civilized persons to savage, authoritarian regimes. At least, this was Fromm’s explanation of the Nazis’ rise to power. A similar analysis could apply to the present degeneration of the Republican Party in the U.S. and to the militant jihadist movement in the Middle East. But Fromm’s analysis is limited. To be sure, capitalism and technology have their drawbacks and these may even contribute to totalitarianism’s appeal, as Fromm shows. But this overlooks what liberal, science-driven societies and savage, totalitarian societies have in common. Both are flights from existential reckoning, as I’ve explained: the one revolves around artificialization (Enlightenment, rationalist values of individual autonomy, which deteriorate until we’re left with the fraud of consumerism), the other around hypersocialization (cult of personality, restoring the sadomasochistic interplay between mythical gods and their worshippers). Fromm ignores the existential effect of the rational enlightenment that brought on modern science, democracy, and capitalism in the first place, the effect being our deification. By deifying ourselves, we prevent our treasured religions from being fiascos and we spare ourselves the horror of living in an inhuman wilderness from which we’re alienated by our hyper-awareness.

We created the modern world to accelerate the rate at which nature is removed from our presence. Contrary to optimists like Steven Pinker, modernity hasn’t fulfilled its promise of democratizing divinity, as I’d put it. Robber barons and more parasitic oligarchs do indeed resort to the older departure of hypersocialization, acting like decadent gods in relation to human slaves instead of focusing their divine creativity on our common enemy, the monstrous wilderness. The internet that trivializes everything it touches and the omnipresence of our high-tech gadgets do infantilize us, turning us into cattle-like consumers instead of unleashing our creativity and training us to be the indomitable warriors that alone could endure the promethean mission. This is because we, being the only gods that exist, are woefully unprepared for our responsibility, having retained our animal heritage in the form of our bodies which infect most of our decisions with natural fears and prejudices. At any rate, the deeper story of the animal that becomes a godlike person to obliterate the source of alienation that’s the curse of any flawed, lonely godling helps explain why we now settle more often for the minor anxieties of living in modern civilization, to avoid the major angst of recognizing the existential importance of what we are.

December 31, 2015

On the Inapplicability of Philosophy to the Future

By way of continuing the excellent conversation started in Lingering: The problem is that we evolved to be targeted, shallow information consumers in unified, deep information environments. As targeted, shallow information consumers we require two things: 1) certain kinds of information hygiene, and 2) certain kinds of background invariance. (1) is already in a state of free-fall, I think, and (2) is on the technological cusp. I don’t see any plausible way of reversing the degradation of either ecological condition, so I see the prospects for traditional philosophical discourses only diminishing. The only way forward that I can see is just being honest to the preposterous enormity of the problem. The thought that rebranding old tools that never delivered back when (1) and (2) were only beginning to erode will suffice now that they are beginning to collapse strikes me as implausible.

December 20, 2015

The Lingering of Philosophy

The ‘Death of Philosophy’ is something that circulates through arterial underbelly of culture with quite some regularity, a theme periodically goosed whenever high-profile scientific figures bother to express their attitudes on the subject. Scholars in the humanities react the same way stakeholders in any institution react when their authority and privilege are called into question: they muster rationalizations, counterarguments, and pejoratives. They rally troops with whooping war-cries of “positivism” or “scientism,” list all the fields of inquiry where science holds no sway, and within short order the whole question of whether philosophy is dead begins to look very philosophical, and the debate itself becomes evidence that philosophy is alive and well—in some respects at least.

The problem with this pattern, of course, is that the terms like ‘philosophy’ or ‘science’ are so overdetermined that no one ends up talking about the same thing. For physicists like Stephen Hawking or Lawrence Krauss or Neil deGrasse Tyson, the death of philosophy is obvious insofar as the institution has become almost entirely irrelevant to their debates. There are other debates, they understand, debates where scientists are the hapless ones, but they see the process of science as an inexorable, and yes, imperialistic one. More and more debates fall within its purview as the technical capacities of science improve. They presume the institution of philosophy will become irrelevant to more and more debates as this process continues. For them, philosophy has always been something to chase away. Since the presence of philosophers in a given domain of inquiry reliably indicates scientific ignorance to important features of that domain, the relevance of philosophers is directly related to the maturity of a science.

They have history on their side.

There will always be speculation—science is our only reliable provender of theoretical cognition, after all. The question of the death of philosophy cannot be the question of the death of theoretical speculation. The death of philosophy as I see it is the death of a particular institution, a discourse anchored in the tradition of using intentional idioms and metacognitive deliverances to provide theoretical solutions. I think science is killing that philosophy as we speak.

The argument is surprisingly direct, and, I think, fatal to intentionalism, but as always, I would love to hear dissenting opinions.

1) Human cognition only has access to the effects of the systems cognized.

2) The mechanical structure of our environments is largely inaccessible.

3) Cognition exploits systematic correlations—‘cues’—between those effects that can be accessed and the systems engaged to solve for those systems.

4) Cognition is heuristic.

5) Metacognition is a form of cognition.

6) Metacognition also exploits systematic correlations—‘cues’—between those effects that can be accessed and the systems engaged to solve for those systems.

7) Metacognition is also heuristic.

8) Metacognition is the product of adventitious adaptations exploiting onboard information in various reproductively decisive ways.

9) The applicability of that ancestral information to second order questions regarding the nature of experience is highly unlikely.

10) The inability of intentionalism to agree on formulations, let alone resolve issues, evidences as much.

11) Intentional cognition is a form of cognition.

12) Intentional cognition also exploits systematic correlations—‘cues’—between those effects that can be accessed and the systems engaged to solve for those systems.

13) Intentional cognition is also heuristic.

14) Intentional cognition is the product of adventitious adaptations exploiting available onboard information in various reproductively decisive ways.

15) The applicability of that ancestral information to second order questions regarding the nature of meaning is highly unlikely.

16) The inability of intentionalism to agree on formulations, let alone resolve issues, evidences as much.

December 13, 2015

Intentional Philosophy as the Neuroscientific Explananda Problem

The problem is basically that the machinery of the brain has no way of tracking its own astronomical dimensionality; it can at best track problem-specific correlational activity, various heuristic hacks. We lack not only the metacognitive bandwidth, but the metacognitive access required to formulate the explananda of neuroscientific investigation.

A curious consequence of the neuroscientific explananda problem is the glaring way it reveals our blindness to ourselves, our medial neglect. The mystery has always been one of understanding constraints, the question of what comes before we do. Plans? Divinity? Nature? Desires? Conditions of possibility? Fate? Mind? We’ve always been grasping for ourselves, I sometimes think, such was the strategic value of metacognitive capacity in linguistic social ecologies. The thing to realize is that grasping, the process of developing the capacity to report on our experience, was bootstapped out of nothing and so comprised the sum of all there was to the ‘experience of experience’ at any given stage of our evolution. Our ancestors had to be both implicitly obvious, and explicitly impenetrable to themselves past various degrees of questioning.

We’re just the next step.

What is it we think we want as our neuroscientific explananda? The various functions of cognition. What are the various functions of cognition? Nobody can seem to agree, thanks to medial neglect, our cognitive insensitivity to our cognizing.

Here’s what I think is a productive way to interpret this conundrum.

Generally what we want is a translation between the manipulative and the communicative. It is the circuit between these two general cognitive modes that forms the cornerstone of what we call scientific knowledge. A finding that cannot be communicated is not a finding at all. The thing is, this—knowledge itself—all functions in the dark. We are effectively black boxes to ourselves. In all math and science—all of it—the understanding communicated is a black box understanding, one lacking any natural understanding of that understanding.

Crazy but true.

What neuroscience is after, of course, is a natural understanding of understanding, to peer into the black box. They want manipulations they can communicate, actionable explanations of explanation. The problem is that they have only heuristic, low-dimensional, cognitive access to themselves: they quite simply lack the metacognitive access required to resolve interpretive disputes, and so remain incapable of formulating the explananda of neuroscience in any consensus commanding way. In fact, a great many remain convinced, on intuitive grounds, that the explananda sought, even if they could be canonically formulated, would necessarily remain beyond the pale of neuroscientific explanation. Heady stuff, given the historical track record of the institutions involved.

People need to understand that the fact of a neuroscientific explananda problem is the fact of our outright ignorance of ourselves. We quite simply lack the information required to decide what it is we’re explaining. What we call ‘philosophy of mind’ is a kind of metacognitive ‘crash space,’ a point where our various tools seem to function, but nothing ever comes of it.

The low-dimensionality of the information begets underdetermination, underdetermination begets philosophy, philosophy begets overdetermination. The idioms involved become ever more plastic, more difficult to sort and arbitrate. Crash space bloats. In a sense, intentional philosophy simply is the neuroscientific explananda problem, the florid consequence of our black box souls.

The thing that can purge philosophy is the thing that can tell you what it is.

December 6, 2015

Alien Philosophy

[Consolidated, with pretty pictures]

The highest species concept may be that of a terrestrial rational being; however, we shall not be able to name its character because we have no knowledge of non-terrestrial rational beings that would enable us to indicate their characteristic property and so to characterize this terrestrial being among rational beings in general. It seems, therefore, that the problem of indicating the character of the human species is absolutely insoluble, because the solution would have to be made through experience by means of the comparison of two species of rational being, but experience does not offer us this. (Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, 225)

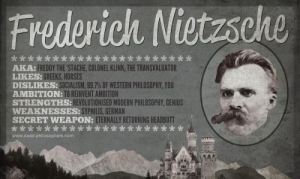

Are there alien philosophers orbiting some faraway star, opining in bursts of symbolically articulated smells, or parsing distinctions-without-differences via the clasp of neural genitalia? What would an alien philosophy look like? Do we have any reason to think we might find some of them recognizable? Do the Greys have their own version of Plato? Is there a little green Nietzsche describing little green armies of little green metaphors?

I: The Story Thus Far

A couple years back, I published a piece in Scientia Salon, “Back to Square One: Toward a Post-intentional Future,” that challenged the intentional realist to warrant their theoretical interpretations of the human. What is the nature of the data that drives their intentional accounts? What kind of metacognitive capacity can they bring to bear?

I asked these questions precisely because they cannot be answered. The intentionalist has next to no clue as to the nature, let alone the provenance, of their data, and even less inkling as to the metacognitive resources at their disposal. They have theories, of course, but it is the proliferation of theories that is precisely the problem. Make no mistake: the failure of their project, their consistent inability to formulate their explananda, let alone provide any decisive explanations, is the primary reason why cognitive science devolves so quickly into philosophy.

But if chronic theoretical underdetermination is the embarrassment of intentionalism, then theoretical silence has to be the embarrassment of eliminativism. If meaning realism offers too much in the way of theory—endless, interminable speculation—then meaning skepticism offers too little. Absent plausible alternatives, intentionalists naturally assume intrinsic intentionality is the only game in town. As a result, eliminativists who use intentional idioms are regularly accused of incoherence, of relying upon the very intentionality they’re claiming to eliminate. Of course eliminativists will be quick to point out the question-begging nature of this criticism: They need not posit an alternate theory of their own to dispute intentional theories of the human. But they find themselves in a dialectical quandary, nonetheless. In the absence of any real theory of meaning, they have no substantive way of actually contributing to the domain of the meaningful. And this is the real charge against the eliminativist, the complaint that any account of the human that cannot explain the experience of being human is barely worth the name. [1] Something has to explain intentional idioms and phenomena, their apparent power and peculiarity; If not intrinsic or original intentionality, then what?

My own project, however, pursues a very different brand of eliminativism. I started my philosophical career as an avowed intentionalist, a one-time Heideggerean and Wittgensteinian. For decades I genuinely thought philosophy had somehow stumbled into ‘Square Two.’ No matter what doubts I entertained regarding this or that intentional account, I was nevertheless certain that some intentional account had to be right. I was invested, and even though the ruthless elegance of eliminativism made me anxious, I took comfort in the standard shibboleths and rationalizations. Scientism! Positivism! All theoretical cognition presupposes lived life! Quality before quantity! Intentional domains require intentional yardsticks!

Then, in the course of writing a dissertation on fundamental ontology, I stumbled across a new, privative way of understanding the purported plenum of the first-person, a way of interpreting intentional idioms and phenomena that required no original meaning, no spooky functions or enigmatic emergences—nor any intentional stances for that matter. Blind Brain Theory begins with the assumption that theoretically motivated reflection upon experience co-opts neurobiological resources adapted to far different kinds of problems. As a co-option, we have no reason to assume that ‘experience’ (whatever it amounts to) yields what philosophical reflection requires to determine the nature of experience. Since the systems are adapted to discharge far different tasks, reflection has no means of determining scarcity and so generally presumes sufficiency. It cannot source the efficacy of rules so rules become the source. It cannot source temporal awareness so the now becomes the standing now. It cannot source decisions so decisions (the result of astronomically complicated winner-take-all processes) become ‘choices.’ The list goes on. From a small set of empirically modest claims, Blind Brain Theory provides what I think is the first comprehensive, systematic way to both eliminate and explain intentionality.

In other words, my reasons for becoming an eliminativist were abductive to begin with. I abandoned intentionalism, not because of its perpetual theoretical disarray (though this had always concerned me), but because I became convinced that eliminativism could actually do a better job explaining the domain of meaning. Where old school, ‘dogmatic eliminativists’ argue that meaning must be natural somehow, my own ‘critical eliminativism’ shows how. I remain horrified by this how, but then I also feel like a fool for ever thinking the issue would end any other way. If one takes mediocrity seriously, then we should expect that science will explode, rather than canonize our prescientific conceits, no matter how near or dear.

But how to show others? What could be more familiar, more entrenched than the intentional philosophical tradition? And what could be more disparate than eliminativism? To quote Dewey from Experience and Nature, “The greater the gap, the disparity, between what has become a familiar possession and the traits presented in new subject-matter, the greater is the burden imposed upon reflection” (Experience and Nature, ix). Since the use of exotic subject matters to shed light on familiar problems is as powerful a tool for philosophy as for my chosen profession, speculative fiction, I propose to consider the question of alien philosophy, or ‘xenophilosophy,’ as a way to ease the burden. What I want to show is how, reasoning from robust biological assumptions, one can plausibly claim that aliens—call them ‘Thespians’—would also suffer their own versions of our own (hitherto intractable) ‘problem of meaning.’ The degree to which this story is plausible, I will contend, is the degree to which critical eliminativism deserves serious consideration. It’s the parsimony of eliminativism that makes it so attractive. If one could combine this parsimony with a comprehensive explanation of intentionality, then eliminativism would very quickly cease to be a fringe opinion.

II: Aliens and Philosophy

Of course, the plausibility of humanoid aliens possessing any kind of philosophy requires the plausibility of humanoid aliens. In popular media, aliens are almost always exotic versions of ourselves, possessing their own exotic versions of the capacities and institutions we happen to have. This is no accident. Science fiction is always about the here and now—about recontextualizations of what we know. As a result, the aliens you tend to meet tend to seem suspiciously humanoid, psychologically if not physically. Spock always has some ‘mind’ with which to ‘meld’. To ask the question of alien philosophy, one might complain, is to buy into this conceit, which although flattering, is almost certainly not true.

And yet the environmental filtration of mutations on earth has produced innumerable examples of convergent evolution, different species evolving similar morphologies and functions, the same solutions to the same problems, using entirely different DNA. As you might imagine, however, the notion of interstellar convergence is a controversial one. [2] Supposing the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence is one thing—cognition is almost certainly integral to complex life elsewhere in the universe—but we know nothing about the kinds of possible biological intelligences nature permits. Short of actual contact with intelligent aliens, we have no way of gauging how far we can extrapolate from our case. [3] All too often, ignorance of alternatives dupes us into making ‘only game in town assumptions,’ so confusing mere possibility with necessity. But this debate need not worry us here. Perhaps the cluster of characteristics we identify with ‘humanoid’ expresses a high-probability recipe for evolving intelligence—perhaps not. Either way, our existence proves that our particular recipe is on file, that aliens we might describe as ‘humanoid’ are entirely possible.

So we have our humanoid aliens, at least as far as we need them here. But the question of what alien philosophy looks like also presupposes we know what human philosophy looks like. In “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man,” Wilfred Sellars defines the aim of philosophy as comprehending “how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term” (1). Philosophy famously attempts to comprehend the ‘big picture.’ The problem with this definition is that it overlooks the relationship between philosophy and ignorance, and so fails to distinguish philosophical inquiry from scientific or religious inquiry. Philosophy is invested in a specific kind of ‘big picture,’ one that acknowledges the theoretical/speculative nature of its claims, while remaining beyond the pale of scientific arbitration. Philosophy is better defined, then, as the attempt to comprehend how things in general hang together in general absent conclusive information.

All too often philosophy is understood in positive terms, either as an archive of theoretical claims, or as a capacity to ‘see beyond’ or ‘peer into.’ On this definition, however, philosophy characterizes a certain relationship to the unknown, one where inquiry eschews supernatural authority, and yet lacks the methodological, technical, and institutional resources of science. Philosophy is the attempt to theoretically explain in the absence of decisive warrant, to argue general claims that cannot, for whatever reason, be presently arbitrated. This is why questions serve as the basic organizing principles of the institution, the shared boughs from which various approaches branch and twig in endless disputation. Philosophy is where we ponder the general questions we cannot decisively answer, grapple with ignorances we cannot readily overcome.

III: Evolution and Ecology

A: Thespian Nature

It might seem innocuous enough defining philosophy in privative terms as the attempt to cognize in conditions of information scarcity, but it turns out to be crucial to our ability to make guesses regarding potential alien analogues. This is because it transforms the question of alien philosophy into a question of alien ignorance. If we can guess at the kinds of ignorance a biological intelligence would suffer, then we can guess at the kinds of questions they would ask, as well as the kinds of answers that might occur to them. And this, as it turns out, is perhaps not so difficult as one might suppose.

The reason is evolution. Thanks to evolution, we know that alien cognition would be bounded cognition, that it would consist of ‘good enough’ capacities adapted to multifarious environmental, reproductive impediments. Taking this ecological view of cognition, it turns out, allows us to make a good number of educated guesses. (And recall, plausibility is all that we’re aiming for here).

So for instance, we can assume tight symmetries between the sensory information accessed, the behavioural resources developed, and the impediments overcome. If gamma rays made no difference to their survival, they would not perceive them. Gamma rays, for Thespians, would be unknown unknowns, at least pending the development of alien science. The same can be said for evolution, planetary physics—pretty much any instance of theoretical cognition you can adduce. Evolution assures that cognitive expenditures, the ability to intuit this or that, will always be bound in some manner to some set of ancestral environments. Evolution means that information that makes no reproductive difference makes no biological difference.