R. Scott Bakker's Blog, page 13

August 9, 2015

Alien Philosophy

The highest species concept may be that of a terrestrial rational being; however, we shall not be able to name its character because we have no knowledge of non-terrestrial rational beings that would enable us to indicate their characteristic property and so to characterize this terrestrial being among rational beings in general. It seems, therefore, that the problem of indicating the character of the human species is absolutely insoluble, because the solution would have to be made through experience by means of the comparison of two species of rational being, but experience does not offer us this. (Kant: Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, 225)

Are there alien philosophers orbiting some faraway star, opining in bursts of symbolically articulated smells, or parsing distinctions-without-differences via the clasp of neural genitalia? What would an alien philosophy look like? Do we have any reason to think we might find some of them recognizable? Do the Greys have their own version of Plato? Is there a little green Nietzsche describing little green armies of little green metaphors?

I: The Story Thus Far

A couple years back, I published a piece in Scientia Salon, “Back to Square One: Toward a Post-intentional Future,” that challenged the intentional realist to warrant their theoretical interpretations of the human. What is the nature of the data that drives their intentional accounts? What kind of metacognitive capacity can they bring to bear?

I asked these questions precisely because they cannot be answered. The intentionalist has next to no clue as to the nature, let alone the provenance, of their data, and even less inkling as to the metacognitive resources at their disposal. They have theories, of course, but it is the proliferation of theories that is precisely the problem. Make no mistake: the failure of their project, their consistent inability to formulate their explananda, let alone provide any decisive explanations, is the primary reason why cognitive science devolves so quickly into philosophy.

But if chronic theoretical underdetermination is the embarrassment of intentionalism, then theoretical silence has to be the embarrassment of eliminativism. If meaning realism offers too much in the way of theory—endless, interminable speculation—then meaning skepticism offers too little. Absent plausible alternatives, intentionalists naturally assume intrinsic intentionality is the only game in town. As a result, eliminativists who use intentional idioms are regularly accused of incoherence, of relying upon the very intentionality they’re claiming to eliminate. Of course eliminativists will be quick to point out the question-begging nature of this criticism: They need not posit an alternate theory of their own to dispute intentional theories of the human. But they find themselves in a dialectical quandary, nonetheless. In the absence of any real theory of meaning, they have no substantive way of actually contributing to the domain of the meaningful. And this is the real charge against the eliminativist, the complaint that any account of the human that cannot explain the experience of being human is barely worth the name. [1] Something has to explain intentional idioms and phenomena, their apparent power and peculiarity; If not intrinsic or original intentionality, then what?

My own project, however, pursues a very different brand of eliminativism. I started my philosophical career as an avowed intentionalist, a one-time Heideggerean and Wittgensteinian. For decades I genuinely thought philosophy had somehow stumbled into ‘Square Two.’ No matter what doubts I entertained regarding this or that intentional account, I was nevertheless certain that some intentional account had to be right. I was invested, and even though the ruthless elegance of eliminativism made me anxious, I took comfort in the standard shibboleths and rationalizations. Scientism! Positivism! All theoretical cognition presupposes lived life! Quality before quantity! Intentional domains require intentional yardsticks!

Then, in the course of writing a dissertation on fundamental ontology, I stumbled across a new, privative way of understanding the purported plenum of the first-person, a way of interpreting intentional idioms and phenomena that required no original meaning, no spooky functions or enigmatic emergences—nor any intentional stances for that matter. Blind Brain Theory begins with the assumption that theoretically motivated reflection upon experience co-opts neurobiological resources adapted to far different kinds of problems. As a co-option, we have no reason to assume that ‘experience’ (whatever it amounts to) yields what philosophical reflection requires to determine the nature of experience. Since the systems adapted to discharge far different tasks, reflection has no means of determining scarcity and so generally presumes sufficiency. It cannot source the efficacy of rules so rules become the source. It cannot source temporal awareness so the now becomes the standing now. It cannot source decisions so decisions (the result of astronomically complicated winner-take-all processes) become ‘choices.’ The list goes on. From a small set of empirically modest claims, Blind Brain Theory provides what I think is the first comprehensive, systematic way to both eliminate and explain intentionality.

In other words, my reasons for becoming an eliminativist were abductive to begin with. I abandoned intentionalism, not because of its perpetual theoretical disarray (though this had always concerned me), but because I became convinced that eliminativism could actually do a better job explaining the domain of meaning. Where old school, ‘dogmatic eliminativists’ argue that meaning must be natural somehow, my own ‘critical eliminativism’ shows how. I remain horrified by this how, but then I also feel like a fool for ever thinking the issue would end any other way. If one takes mediocrity seriously, then we should expect that science will explode, rather than canonize our prescientific conceits, no matter how near or dear.

But how to show others? What could be more familiar, more entrenched than the intentional philosophical tradition? And what could be more disparate than eliminativism? To quote Dewey from Experience and Nature, “The greater the gap, the disparity, between what has become a familiar possession and the traits presented in new subject-matter, the greater is the burden imposed upon reflection” (Experience and Nature, ix). Since the use of exotic subject matters to shed light on familiar problems is as powerful a tool for philosophy as for my chosen profession, speculative fiction, I propose to consider the question of alien philosophy, or ‘xenophilosophy,’ as a way to ease the burden. What I want to show is how, reasoning from robust biological assumptions, one can plausibly claim that aliens—call them ‘Thespians’—would also suffer their own versions of our own (hitherto intractable) ‘problem of meaning.’ The degree to which this story is plausible, I will contend, is the degree to which critical eliminativism deserves serious consideration. It’s the parsimony of eliminativism that makes it so attractive. If one could combine this parsimony with a comprehensive explanation of intentionality, then eliminativism would very quickly cease to be a fringe opinion.

II: Aliens and Philosophy

Of course, the plausibility of humanoid aliens possessing any kind of philosophy requires the plausibility of humanoid aliens. In popular media, aliens are almost always exotic versions of ourselves, possessing their own exotic versions of the capacities and institutions we happen to have. This is no accident. Science fiction is always about the here and now—about recontextualizations of what we know. As a result, the aliens you tend to meet tend to seem suspiciously humanoid, psychologically if not physically. Spock always has some ‘mind’ with which to ‘meld’. To ask the question of alien philosophy, one might complain, is to buy into this conceit, which although flattering, is almost certainly not true.

And yet the environmental filtration of mutations on earth has produced innumerable examples of convergent evolution, different species evolving similar morphologies and functions, the same solutions to the same problems, using entirely different DNA. As you might imagine, however, the notion of interstellar convergence is a controversial one. [2] Supposing the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence is one thing—cognition is almost certainly integral to complex life elsewhere in the universe—but we know nothing about the kinds of possible biological intelligences nature permits. Short of actual contact with intelligent aliens, we have no way of gauging how far we can extrapolate from our case. [3] All too often, ignorance of alternatives dupes us into making ‘only game in town assumptions,’ so confusing mere possibility with necessity. But this debate need not worry us here. Perhaps the cluster of characteristics we identify with ‘humanoid’ expresses a high-probability recipe for evolving intelligence—perhaps not. Either way, our existence proves that our particular recipe is on file, that aliens we might describe as ‘humanoid’ are entirely possible.

So we have our humanoid aliens, at least as far as we need them here. But the question of what alien philosophy looks like also presupposes we know what human philosophy looks like. In “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man,” Wilfred Sellars defines the aim of philosophy as comprehending “how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term” (1). Philosophy famously attempts to comprehend the ‘big picture.’ The problem with this definition is that it overlooks the relationship between philosophy and ignorance, and so fails to distinguish philosophical inquiry from scientific or religious inquiry. Philosophy is invested in a specific kind of ‘big picture,’ one that acknowledges the theoretical/speculative nature of its claims, while remaining beyond the pale of scientific arbitration. Philosophy is better defined, then, as the attempt to comprehend how things in general hang together in general absent conclusive information.

All too often philosophy is understood in positive terms, either as an archive of theoretical claims, or as a capacity to ‘see beyond’ or ‘peer into.’ On this definition, however, philosophy characterizes a certain relationship to the unknown, one where inquiry eschews supernatural authority, and yet lacks the methodological, technical, and institutional resources of science. Philosophy is the attempt to theoretically explain in the absence of decisive warrant, to argue general claims that cannot, for whatever reason, be presently arbitrated. This is why questions serve as the basic organizing principles of the institution, the shared boughs from which various approaches branch and twig in endless disputation. Philosophy is where we ponder the general questions we cannot decisively answer, grapple with ignorances we cannot readily overcome.

III: Evolution and Ecology

A: Thespian Nature

It might seem innocuous enough, defining philosophy in privative terms, as the attempt to cognize in conditions of information scarcity, but it turns out to be crucial to our ability to make guesses regarding potential alien analogues. This is because it transforms the question of alien philosophy into a question of alien ignorance. If we can guess at the kinds of ignorance a biological intelligence would suffer, then we can guess at the kinds of questions they would ask, as well as the kinds of answers that might occur to them. And this, as it turns out, is perhaps not so difficult as one might suppose.

The reason is evolution. Thanks to evolution, we know that alien cognition would be bounded cognition, that it would consist of ‘good enough’ capacities adapted to multifarious environmental, reproductive impediments. Taking this ecological view of cognition, it turns out, allows us to make a good number of educated guesses. (And recall, plausibility is all that we’re aiming for here).

So for instance, we can assume tight symmetries between the sensory information accessed, the behavioural resources developed, and the impediments overcome. If gamma rays made no difference to their survival, they would not perceive them. Gamma rays, for Thespians, would be unknown unknowns, at least pending the development of alien science. The same can be said for evolution, planetary physics—pretty much any instance of theoretical cognition you can adduce. Evolution assures that cognitive expenditures, the ability to intuit this or that, will always be bound in some manner to some set of ancestral environments. Evolution means that information that makes no reproductive difference makes no biological difference.

An ecological view, in other words, allows us to naturalistically motivate something we might have been tempted to assume outright: original naivete. The possession of sensory and cognitive apparatuses comparable to our own means Thespians will possess a humanoid neglect structure, a pattern of ignorances they cannot even begin to question, that is, pending the development of philosophy. The Thespians would not simply be ignorant of the microscopic and macroscopic constituents and machinations explaining their environments, they would be oblivious to them. Like our own ancestors, they wouldn’t even know they didn’t know.

Theoretical knowledge is a cultural achievement. Our Thespians would have to learn the big picture details underwriting their immediate environments, undergo their own revolutions and paradigm shifts as they accumulate data and refine interpretations. We can expect them to possess an implicit grasp of local physics, for instance, but no explicit, theoretical understanding of physics in general. So Thespians, it seems safe to say, would have their own version of natural philosophy, a history of attempts to answer big picture questions about the nature of Nature in the absence of decisive data.

Not only can we say their nascent, natural theories will be underdetermined, we can also say something about the kinds of problems Thespians will face, and so something of the shape of their natural philosophy. For instance, needing only the capacity to cognize movement within inertial frames, we can suppose that planetary physics would escape them. Quite simply, without direct information regarding the movement of the ground, the Thespians would have no sense of the ground changing position. They would assume that their sky was moving, not their world. Their cosmological musings, in other words, would begin supposing ‘default geocentrism,’ an assumption that would only require rationalization once others, pondering the movement of the skies, began posing alternatives.

One need only read On the Heavens to appreciate how the availability of information can constrain a theoretical debate. Given the imprecision of the observational information at his disposal, for instance, Aristotle’s stellar parallax argument becomes well-nigh devastating. If the earth revolves around the sun, then surely such a drastic change in position would impact our observations of the stars, the same way driving into a city via two different routes changes our view of downtown. But Aristotle, of course, had no decisive way of fathoming the preposterous distances involved—nor did anyone, until Galileo turned his Dutch Spyglass to the sky. [4]

Aristotle, in other words, was victimized not so much by poor reasoning as by various perspectival illusions following from a neglect structure we can presume our Thespians share. And this warrants further guesses. Consider Aristotle’s claim that the heavens and the earth comprise two distinct ontological orders. Of course purity and circles rule the celestial, and of course grit and lines rule the terrestrial—that is, given the evidence of the naked eye from the surface of the earth. The farther away something is, the less information observation yields, the fewer distinctions we’re capable of making, the more uniform and unitary it is bound to seem—which is to say, the less earthly. An inability to map intuitive physical assumptions onto the movements of the firmament, meanwhile, simply makes those movements appear all the more exceptional. In terms of the information available, it seems safe to suppose our Thespians would at least face the temptation of Aristotle’s long-lived ontological distinction.

I say ‘temptation,’ because certainly any number of caveats can be raised here. Heliocentrism, for instance, is far more obvious in our polar latitudes (where the earth’s rotation is as plain as the summer sun in the sky), so there are observational variables that could have drastically impacted the debate even in our own case. Who knows? If it weren’t for the consistent failure of ancient heliocentric models to make correct predictions (the models assumed circular orbits), things could have gone differently in our own history. The problem of where the earth resides in the whole might have been short-lived.

But it would have been a problem all the same, simply because the motionlessness of the earth and the relative proximity of the heavens would have been our (erroneous) default assumptions. Bound cognition suggests our Thespians would find themselves in much the same situation. Their world would feel motionless. Their heavens would seem to consist of simpler stuff following different laws. Any Thespian arguing heliocentrism would have to explain these observations away, argue how they could be moving while standing still, how the physics of the ground belongs to the physics of the sky.

We can say this because, thanks to an ecological view, we can make plausible empirical guesses as to the kinds of information and capacities Thespians would have available. Not only can we predict what would have remained unknown unknowns for them, we can also predict what might be called ‘unknown half-knowns.’ Where unknown unknowns refer to things we can’t even question, unknown half-knowns refer to theoretical errors we cannot perceive simply because the information required to do so remains—you guessed it—unknown unknown.

Think of Plato’s allegory of the cave. The chained prisoners confuse the shadows for everything because, unable to move their heads from side to side, they just don’t ‘know any different.’ This is something we understand so intuitively we scarce ever pause to ponder it: the absence of information or cognitive capacity has positive cognitive consequences. Absent certain difference making differences, the ground will be cognized as motionless rather than moving, and celestial objects will be cognized as simples rather than complex entities in their own right. The ground might as well be motionless and the sky might as well be simple as far as evolution is concerned. Once again, distinctions that make no reproductive difference make no biological difference. Our lack of radio telescope eyes is no genetic or environmental fluke: such information simply wasn’t relevant to our survival.

This means that a propensity to theorize ‘ground/sky dualism’ is built into our biology. This is quite an incredible claim, if you think about it, but each step in our path has been fairly conservative, given that mere plausibility is our aim. We should expect Thespian cognition to be bounded cognition. We should expect them to assume the ground motionless, and the constituents of the sky simple. We can suppose this because we can suppose them to be ignorant of their ignorances, just as we were (and remain). Cognizing the ontological continuity of heaven and earth requires the proper data for the proper interpretation. Given a roughly convergent sensory predicament, it seems safe to say that aliens would be prone as we were to mistake differences in signal with differences in being and so have to discover the universality of nature the same as we did.

But if we can assume our Thespians—or at least some of them—would be prone to misinterpret their environments the way we did, what about themselves? For centuries now humanity has been revising and sharpening its understanding of the cosmos, to the point of drafting plausible theories regarding the first second of creation, and yet we remain every bit as stumped regarding ourselves as Aristotle. Is it fair to say that our Thespians would suffer the same millennial myopia?

Would they have their own version of our interminable philosophy of the soul?

Notes

[1] The eliminativism at issue here is meaning eliminativism, and not, as Stich, Churchland, and many others have advocated, psychological eliminativism. But where meaning eliminativism clearly entails psychological eliminativism, it is not at all obvious the psychological eliminativism entails meaning eliminativism. This was why Stich, found himself so perplexed by the implications of reference (see his, Deconstructing the Mind, especially Chapter 1). To assume that folk psychology is a mistaken theory is to assume that folk psychology is representational, something that is true or false of the world. The critical eliminativism espoused here suffers no such difficulty, but at the added cost of needing to explain meaning in general, and not simply commonsense human psychology.

[2] See Kathryn Denning’s excellent, “Social Evolution in Cosmic Context,” http://www.nss.org/resources/library/spacepolicy/Cosmos_and_Culture_NASA_SP4802.pdf

[3] Nicolas Rescher, for instance, makes hash of the time-honoured assumption that aliens would possess a science comparable to our own by cataloguing the myriad contingencies of the human institution. See Finitude, 28, or Unknowability, “Problems of Alien Cognition,” 21-39.

[4] Stellar parallax, on this planet at least, was not measured until 1838.

July 26, 2015

Stuff to Blow your… Brains.

Helen de Cruz, a philosopher of religion and cognitive science at VU Amsterdam, has posted her interview of me in Philosophical Percolations. I’d like to thank Helen for both her interest and her questions, which are designed to air different philosopher’s views of the importance of fiction to philosophy.

Also, the Consult Skin Spies were recently featured as the ‘Monster of the Week’ over at Stuff to Blow your Mind. Many thanks to bakkerfans for spying that one!

The way cool StarShipSofa has published an audio version of Reinstalling Eden, the short story that Eric Schwitzgebel and I published in Nature. My thanks to Jeremy Szal for that one (and also my apologies for posting this link so late).

And lastly, I spoke to Erik Hane, my US editor, last week, and he asked me to assure everyone that Overlook is very committed to the series, so there’s no reason to plague them with calls (apparently someone tweeted their phone number!). Publication dates, as well as some big announcements regarding the future of the series, will be made soon. I have to tell you, I feel like Achamian most of the time: it’s hard to express just how gratifying it is to be believed now and again. Seriously, thanks to you all.

July 22, 2015

The Kosmos Biblioth

Hey all! Roger here. I wanted to let you guys know that I now have an author blog of my own, called the Kosmos Biblioth. I hope you’ll drop by and say hello, tell me what you think.

July 13, 2015

Posthuman Life Goes Live

I just returned from the deep north… with any luck I’ll have my old routines up and running within a week or two.

Figure/Ground has published my interview of David Roden on his seminal Posthuman Life: Philosophy at the Edge of the Human. It’s pretty wank at turns, but I wanted to see just how far out on the edge David was willing to go! For those interested, Craig Hickman has an excellent series of posts reviewing the book chapter by chapter over at Dark Ecologies, but I urge fellow wankers to read the book itself. David has provided what is the most concise picture of the academic posthumanities we’re likely to see for some time, and I think the adoption of his terminology, if not his views, will allow the debate to rise above the confusion. The fine folks at Philosophical Percolations have been quick to recognize the book’s importance, and have already begun what promises to be a fascinating summer reading group.

If you have any questions, hash them out there, or here, or on David’s own blog, the always excellent Enemy Industry, where many of the articles developing his argument can also be found.

July 1, 2015

The Lesser Sound and Fury

So a storm blew through last Tuesday night, a real storm, the kind we haven’t seen in a couple of years at least. I was just finishing up a disastrous night of NHL 13 (because NHL 14 is a rip off) on PS3 (because my PS4 is a paperweight) with my buds out back in the garage. Frank fled. Ken strolled. ‘Good night, Motherfucker.’ ‘Goodnight.’ The sky was alive, strobes glimpsed through the Dark Lord’s laundry, thunder rattling the teeth of the world, booming across houses lined up like molars. I sat on the front porch to watch, squinting more for the booze than for the wind. There had been talk of tornados, but I wasn’t buying it, having lived in Tennessee. No, just a storm. We just don’t get the parking lot heat they need to germinate, let alone to feed. The air lacked the required energy.

The rain fell like gravel. Straight down. Euclidean rain, I thought.

But there was nothing linear about the lightning. The first strike ripped fabric too fundamental to be seen. The second had me out of my stupor as much as out of my seat, blinking for the instantaneous execution of night and shadow. Everything revealed God’s way: too quick to be grasped by eyes so small as these.

I stood, another animal floating in solution. I laughed the laugh of monkeys too stupid to cower. I thought of ancient fools.

The rain fell like gravel, massing across all the terrestrial surfaces, hard enough to shatter into sand, hanging like dust across ankles in summer fields. Then it faded, trailed into silence with analogue perfection, and I found myself standing in a glazed nocturnal world, everything turgid… shivering for the high-altitude chill.

I locked up the house, crawled into bed. I lay in bed listening to the passage of thunder… the far side of some cataclysmic charge. I watched white splash across the skylights.

And then came the blitz.

BOOM!

Something—an artillery shell pilfered from some World War I magazine from the sounds of it—exploded just a few blocks over. The house shook everyone awake.

BOOM!

Closer than the last—even nature believes in the strategic value of carpet bombing.

We huddled together, our small family of three, grinning for terror and wonder. I spoke brave words I can no longer remember.

BOOM!

Loud enough to crack wood, to swear in front of little children.

The next morning I awoke to the smell of a five year old farting. It seemed a miracle that everything was intact and sodden—no hoary old trees torn from their sockets, no branches hanging necks broken from powerlines. It seemed miraculous that a beast so vast could stomp through our neighbourhood with nary a casualty. Not a shrub. Not one drowned squirrel.

Only my fucking modem, and a week to remember what it was like, back before all this lesser sound and fury.

June 20, 2015

In the Shadow of Summer…

Just an update, given that the inevitable summer disruption of my habitual routines seems to have already commenced.

First, SFF World aficionados were kind enough to include The Prince of Nothing in their top twenty all time best fantasy series.

Second, I gave a version of a science fiction novella I wrote entitled White Rain Country to my agent, who loves it. Hopefully, I should have some publication news soon.

I also submitted the short story solicited by the esteemed Midwest Studies in Philosophy for their special issue on philosophy and science fiction. Apparently there’s some worries about the ‘uncooked’ nature of the content, so some kind revisions might be necessary.

And lastly, things keep dragging on with my publishers regarding The Unholy Consult. My delay turning the manuscript in and the quick turnover of editorial staff in the industry means that no one was up to speed on the series–but six months on from submission, and still we have no word. My fear (not my agent’s) is that they might be re-evaluating their commitment to the series–the way all publishers are reviewing their commitments to their midlist authors. I know for a fact that other publishers are interested in snapping the series up, so there’s no need to organize a wake, but who knows what kind of delay would result. Perhaps shooting them emails explaining why they should believe this series will continue growing might help? I dunno.

The market only grows more and more crowded, and still there’s nothing quite like The Second Apocalypse. Distinction is key in this day and age…

I hope!

June 7, 2015

A Bestiary of Future Literatures (Reprise)

[Apropos my presentation in Denmark, I thought it worthwhile reposting this little gem from the TPB vault…]

With the collapse of mainstream literary fiction as a commercially viable genre in 2036 and its subsequent replacement with Algorithmic Sentimentalism, so-called ‘human literature’ became an entirely state and corporate funded activity. Freed from market considerations, writers could concentrate on accumulating the ingroup prestige required to secure so-called ‘non-reciprocal’ sponsors. In the wake of the new sciences, this precipitated an explosion of ‘genres,’ some self-consciously consolatory, others bent on exploring life in the wake of the so-called ‘Semantic Apocalypse,’ the scientific discrediting of meaning and morality that remains the most troubling consequence of the ongoing (and potentially never-ending) Information Enlightenment.

Amar Stevens, in his seminal Muse: The Exorcism of the Human, famously declared this the age of ‘Post-semanticism,’ where, as he puts it, “writers write with the knowledge that they write nothing” (7). He maps post-semantic literature according to its ‘meaning stance,’ the attitude it takes to the experience of meaning both in the text and the greater world, dividing it into four rough categories: 1) Nostalgic Prosemanticism, which he describes as “a paean to a world that never was” (38); 2) Revisionary Prosemanticism, which attempts “to forge new meaning, via forms of quasi-Nietzschean affirmation, out of the sciences of the soul” (122); 3) Melancholy Antisemanticism, which “embraces the death of meaning as an irredeemable loss” (243); and 4) Neonihilism, which he sees as “the gleeful production of novel semantic illusions via the findings of cognitive neuroscience” (381).

Stevens ends Muse with his famous declaration of the ‘death of literature’:

“For the sum of human history, storytelling, or ‘literature,’ has framed our identity, ordered our lives, and graced our pursuits with the veneer of transcendence. It seemed to be the baseline, the very ‘sea-level’ of what it meant to be human. But now that science has drained the black waters, we can see we have been stranded on lonely peaks all along, and that the wholesome family of meaning was little more than an assemblage of unrelated strangers. We were as ignorant of literature as you are ignorant of the monstrous complexities concealed by these words. Until now, all literature was confabulation, lies that we believed. Until now, we could enthral one another in good conscience. At last we can see there was never any such thing as ‘literature,’ realize that it was of a piece with the trick of perspective we once called the soul” (498)

Algorithmic Sentimentalism: Freely disseminated computer-generated fiction based on the neuronarrative feedback work of Dr. Hilary Kohl, designed to maximize the possibilities of product placement while engendering the ‘mean peak narrative response,’ or story-telling pleasure. Following the work of neurolinguist Pavol Berman, whose ‘Whole Syntax Theory’ is credited with transforming linguistics into a properly natural science, Kohl developed the imaging techniques that allowed her to isolate what she called Subexperiential Narrative Grammar (SNG), and so, like Berman before her, provided narratology with its scientific basis. “Once we were able to isolate the relevant activation architecture, the grammar and its permutations became clear as a road map,” she explained in a 2035 OWN interview. “Then it was simply a matter of imaging people while they read the story-telling greats, and deriving the algorithms needed to generate new heart-touching and gut-wrenching novels.

In 2033, she founded the publishing startup, Muse, releasing algorithmically produced novels for free and generating revenue through the sale of corporate product placements. Initial skepticism was swept away in 2034, when Imp, the story of a small boy surviving the tribulations of ‘social sanctioning’ in a Haitian public school, won the Pulitzer, the National Book Award, and was short-listed for the Man Booker. In 2040, Muse purchased Bertelsmann to become the largest publisher in the world.

In a recent Salon interview, Kohl claimed to have developed what she called Submorphic Adaptation Algorithms that could “eventually replace all literature, even the so-called avante garde fringe.” In a rebuttal piece that appeared in the New York Times, she outraged academics by claiming “Shakespeare only seems deep because we can’t see past the skin of what is really going on, and what has been all along.”

Mundane Fantasy (aka, the ‘mundane fantastic’ or ‘nostalgic realism’ in academic circles): According to Stevens, the primary nostalgic prosemantic genre, the “vestigial remnant of what was once the monumental edifice of mainstream literary fiction” (39).

Technorealism: According to Stevens, the primary revisionary pro-semantic genre, where the traditional narrative form remains as “something to be gamed and/or problematized” (Muse, 45) in the context of “imploding social realities” (46).

Neuroexperimentalism: Movement founded by Gregor Shin, which uses data-mining to isolate so-called ‘orthogonalities,’ a form of lexical and sentential ‘combinetrics’ that generate utterly novel semantic effects.

Impersonalism: A major literary school (commonly referred to as ‘It Lit’) centred around the work of Michel Grant (who famously claims to be the illegitimate son of the late Michel Houellebecq, even though DNA evidence has proved otherwise), which has divided into a least two distinct movements, Hard Impersonalism, where no intentional concepts are used whatsoever, and Soft Impersonalism, where only the so-called ‘Intentionalities of the Self’ are eschewed.

New Absurdism: A growing, melancholy anti-semantic movement inspired by the writing of Tuck Gingrich, noted for what Stevens calls, “its hysterical anti-realism.” Mira Gladwell calls it the ‘meta-meta’ – or ‘meta-squared’ – for the way it continually takes itself as its object of reference. In “One for One for One,” a small position piece published in The New Yorker, the famously reclusive Gingrich seems to argue (the text is notoriously opaque) that “meta-inclusionary satire” constitutes a form of communication that algorithmic generation can never properly duplicate. To date, neither Muse nor Penguin-Narratel have managed to disprove his claim. A related genre called Anthroplasticism has recently found an enthusiastic audience in literary science departments across eastern China and, ironically enough, the southern USA.

Extinctionism: The so-called ‘cryptic school’ thought by many to be algorithmic artifacts, both because of the volume and anonymity of texts available. However, Sheila Siddique, the acclaimed author of Without, has recently claimed connection to the school, stating that the anonymity of authorship is crucial to the authenticity of the genre, which eschews all notions of agency.

June 5, 2015

Writing After the Death of Meaning

Abstract: For centuries now, science has been making the invisible visible, thus revolutionizing our understanding of and power over different traditional domains of knowledge. Fairly all the speculative phantoms have been exorcised from the world, ‘disenchanted,’ and now, at long last, the insatiable institution has begun making the human visible for what it is. Are we the last ancient delusion? Is the great, wheezing heap of humanism more an artifact of ignorance than insight? We have ample reason to think so, and as the cognitive sciences creep ever deeper into our biological convolutions, the ‘worst case scenario’ only looms darker on the horizon. To be a writer in this age is stand astride this paradox, to trade in communicative modes at once anchored to our deepest notions of authenticity and in the process of being dismantled or worse, simulated. If writing is a process of making visible, communicating some recognizable humanity, how does it proceed in an age where everything is illuminated and inhuman? All revolutions require experimentation, but all too often experimentation devolves into closed circuits of socially inert production and consumption. The present revolution, I will argue, requires cultural tools we do not yet possess (or know how to use), and a sensibility that existing cultural elites can only regard as anathema. Writing in the 21st century requires abandoning our speculative past, and seeing ‘literature’ as praxis in a time of unprecedented crisis, as ‘cultural triage.’ Most importantly, writing after the death of meaning means communicating to what we in fact are, and not to the innumerable conceits of obsolescent tradition.

So, we all recognize the revolutionary potential of technology and the science that makes it possible. This is just to say that we all expect science will radically remake those traditional domains that fall within its bailiwick. Likewise, we all appreciate that the human is just such a domain. We all realize that some kind of revolution is brewing…

The only real question is one of how radically the human will be remade. Here, everyone differs, and in quite predictable ways. No matter what position people take, however, they are saying something about the cognitive status of traditional humanistic thought. Science makes myth of traditional ontological claims, relegates them to the history of ideas. So all things being equal we should suppose that science will make myth of traditional ontological claims regarding the human as well. Declaring that traditional ontological claims regarding the human will not suffer the fate of other traditional ontological claims more generally, amounts to declaring that all things are not equal when it comes to the human, that in this one domain at least, traditional modes of cognition actually tell us what is the case.

Let’s call this pole of argumentation humanistic exceptionalism. Any position that contends or assumes that science will not fundamentally revolutionize our understanding of the human supposes that something sets the human apart. Not surprisingly, given the underdetermined nature of the subject-matter, the institutionally entrenched nature of the humanities, and the human propensity to rationalize conceit and self-interests, the vast majority of theorists find themselves occupying this pole. There are, we now know, many, many ways to argue exceptionalism, and no way whatsoever to decisively arbitrate between any them.

What all of them have in common, I think it’s fair to say, is the signature theoretical function they accord to meaning. Another feature they share is a common reliance on pejoratives to police the boundaries of their discourse. Any time you encounter the terms ‘scientism’ or ‘positivism’ or ‘reductionism’ deployed without any corresponding consideration of the case against traditional humanism, you are almost certainly reading an exceptionalist discourse. One of the great limitations of committing to status-quo underdetermined discourses, of course, is the infrequency with which adherents encounter the limits of their discourse, and thus run afoul the same fluency and only game in town effects that render all dogmatic pieties self-perpetuating.

My artistic and philosophical project can be fairly summarized, I think, as a sustained critique of humanistic exceptionalism, an attempt to reveal these positions as the latest (and therefore most difficult to recognize) attempts to intellectually rationalize what are ultimately run-of-the-mill conceits, specious ways to set humanity—or select portions of it at least—apart from nature.

I occupy the lonely pole of argumentation, the one that says humans are not ontologically special in any way, and that accordingly, we should expect the scientific revolution of the human to be as profound as the scientific revolution of any other domain. My whole career is premised on arguing the worst case scenario, the future where humanity finds itself every bit as disenchanted—every bit as debunked—as the cosmos.

I understand why my pole of the debate is so lonely. One of the virtues of my position, I think anyway, lies in its ability to explain its own counter-intuitiveness.

Think about it. What does it mean to say meaning is dead? Surely this is metaphorical hyperbole, or worse yet, irresponsible alarmism. What could my own claims mean otherwise?

‘Meaning,’ on my account, will die two deaths, one theoretical or philosophical, the other practical or functional. Where the first death amounts to a profound cultural upheaval on a par with, say, Darwin’s theory of evolution, the second death amounts to a profound biological upheaval, a transformation of cognitive habitat more profound than any humanity has ever experienced.

‘Theoretical meaning’ simply refers to the endless theories of intentionality humanity has heaped on the question of the human. Pretty much the sum of traditional philosophical thought on the nature of humanity. And this form of meaning I think is pretty clearly dead. People forget that every single cognitive scientific discovery amounts to a feature of human nature that human nature is prone to neglect. We are, as a matter of empirical fact, fundamentally blind to what we are and what we do. Like traditional theoretical claims belonging to other domains, all traditional theoretical claims regarding the human neglect the information driving scientific interpretations. The question is one of what this naturally neglected information—or ‘NNI’—means.

The issue NNI poses for the traditional humanities is existential. If one grants that the sum of cognitive scientific discovery is relevant to all senses of the human, you could safely say the traditional humanities are already dwelling in a twilight of denial. The traditionalist’s strategy, of course, is to subdivide the domain, to adduce arguments and examples that seem to circumscribe the relevance of NNI. The problem with this strategy, however, is that it completely misconstrues the challenge that NNI poses. The traditional humanities, as cognitive disciplines, fall under the purview of cognitive sciences. One can concede that various aspects of humanity need not account for NNI, yet still insist that all our theoretical cognition of those aspects does…

And quite obviously so.

The question, ‘To what degree should we trust ‘reflection upon experience’?’ is a scientific question. Just for example, what kind of metacognitive capacities would be required to abstract ‘conditions of possibility’ from experience? Likewise, what kind of metacognitive capacities would be required to generate veridical descriptions of phenomenal experience? Answers to these kinds of questions bear powerfully on the viability of traditional semantic modes of theorizing the human. On the worst case scenario, the answers to these and other related questions are going to systematically discredit all forms of ‘philosophical reflection’ that fail to take account of NNI.

NNI, in other words, means that philosophical meaning is dead.

‘Practical meaning’ refers to the everyday functionality of our intentional idioms, the ways we use terms like ‘means’ to solve a wide variety of practical, communicative problems. This form of meaning lives on, and will continue to do so, only with ever-diminishing degrees of efficacy. Our everyday intentional idioms function effortlessly and reliably in a wide variety of socio-communicative contexts despite systematically neglecting everything cognitive science has revealed. They provide solutions despite the scarcity of data.

They are heuristic, part of a cognitive system that relies on certain environmental invariants to solve what would otherwise be intractable problems. They possess adaptive ecologies. We quite simply could not cope if we were to rely on NNI, say, to navigate social environments. Luckily, we don’t have to, at least when it comes to a wide variety of social problems. So long as human brains possess the same structure and capacities, the brain can quite literally ignore the brain when solving problems involving other brains. It can leap to conclusions absent any natural information regarding what actually happens to be going on.

But, to riff on Uncle Ben, with great problem-solving economy comes great problem-making potential. Heuristics are ecological; they require that different environmental features remain invariant. Some insects, most famously moths, use ‘transverse orientation,’ flying at a fixed angle to the moon to navigate. Porch lights famously miscue this heuristic mechanism, causing the insect to chase the angle into the light. The transformation of environments, in other words, has cognitive consequences, depending on the kind of short cut at issue. Heuristic efficiency means dynamic vulnerability.

And this means not only that heuristics can be short-circuited, they can also be hacked. Think of the once omnipresent ‘bug zapper.’ Or consider reed warblers, which provide one of the most dramatic examples of heuristic vulnerability nature has to offer. The system they use to recognize eggs and offspring is so low resolution (and therefore economical) that cuckoos regularly parasitize their nests, leaving what are, to human eyes, obviously oversized eggs and (brood-killing) chicks that the warbler dutifully nurses to adulthood.

All cognitive systems, insofar as they are bounded, possess what might be called a Crash Space describing all the possible ways they are prone to break down (as in the case of porch lights and moths), as well as an overlapping Cheat Space describing all the possible ways they can be exploited by competitors (as in the case of reed warblers and cuckoos, or moths and bug-zappers).

The death of practical meaning simply refers to the growing incapacity of intentional idioms to reliably solve various social problems in radically transformed sociocognitive habitats. Even as we speak, our environments are becoming more ‘intelligent,’ more prone to cue intentional intuitions in circumstances that quite obviously do not warrant them. We will, very shortly, be surrounded by countless ‘pseudo-agents,’ systems devoted to hacking our behaviour—exploiting the Cheat Space corresponding to our heuristic limits—via NNI. Combined with intelligent technologies, NNI has transformed consumer hacking into a vast research programme. Our social environments are transforming, our native communicative habitat is being destroyed, stranding us with tools that will increasingly let us down.

Where NNI itself delegitimizes traditional theoretical accounts of meaning (by revealing the limits of reflection), it renders practical problem-solving via intentional idioms (practical meaning) progressively more ineffective by enabling the industrial exploitation of Cheat Space. Meaning is dead, both as a second-order research programme and, more alarmingly, as a first-order practical problem-solver. This—this is the world that the writer, the producer of meaning, now finds themselves writing in as well as writing to. What does it mean to produce ‘content’ in such a world? What does it mean to write after the death of meaning?

This is about as open as a question can be. It reveals just how radical this particular juncture in human thought is about to become. Everything is new, here folks. The slate is wiped clean.

Post-Posterity Writing

The Artist can no longer rely on posterity to redeem ingroup excesses. He or she must either reach out, or risk irrelevance and preposterous hypocrisy. Post-semantic writing is post-posterity writing, the production of narratives for the present rather than some indeterminate tomorrow.

High Dimensional Writing

The Artist can no longer pretend to be immaterial. Nor can they pretend to be something material magically interfacing with something immaterial. They need to see the apparent lack of dimensionality pertaining to all things ‘semantic’ as the product of cognitive incapacity, not ontological exceptionality. They need to understand that thoughts are made of meat. Cognition and communication are biological processes, open to empirical investigation and high dimensional explanations.

Cheat Space Writing

The Artist must exploit Cheat Spaces as much as reveal Cheat Spaces. NNI is not simply an industrial and commercial resource; it is also an aesthetic one.

Cultural Triage

The Artist must recognize that it is already too late, that the processes involved cannot be stopped, let alone reversed. Extremism is the enemy here, the attempt to institute, either via coercive simplification (a la radical Islam, for instance) or via technical reduction (a la totalized surveillance, for instance), Orwellian forms of cognitive hygiene.

May 25, 2015

More Disney than Disney World: Semiotics as Theoretical Make-believe (II)

III: The Gilded Stage

We are one species among 8.7 million, organisms embedded in environments that will select us the way they have our ancestors for 3.8 billion years running. Though we are (as a matter of empirical fact) continuous with our environments, the information driving our environmental behaviour is highly selective. The selectivity of our environmental sensitivities means that we are encapsulated, both in terms of the information available to our brain, and in terms of the information available for consciousness. Encapsulation simply follows from the finite, bounded nature of cognition. Human cognition is the product of ancestral human environments, a collection of good enough fixes for whatever problems those environments regularly posed. Given the biological cost of cognition, we should expect that our brains have evolved to derive as much information as possible from whatever signals available, to continually jump to reproductively advantageous conclusions. We should expect to be insensitive to the vast majority of information in our environments, to neglect everything save information that had managed to get our ancestors born.

As it turns out, shrewd guesswork carried the cognitive day. The correlate of encapsulated information access, in other words, is heuristic cognitive processing, a tendency to always see more than there really is.

So consider the streetscape from above once again:

This looks like a streetscape only because the information provided generally cues the existence of hidden dimensions, which in this case simply do not exist. Since the cuing is always automatic and implicit, you just are looking down a street. Change your angle of access and the illusion of hidden dimensions—which is to say, reality—abruptly evaporates. The impossible New York skyline is revealed as counterfeit.

Let’s call a stage any environment that reliably cues the cognition of alternate environments. On this definition, a stage could be the apparatus of a trapdoor spider, say, or a nest parasitized by a cuckoo, or a painting, or an epic poem, or yes, Disney World—any environment that reliably triggers the cognition of some environment other than the environment actually confronting some organism.

As the inclusion of the spider and the cuckoo should suggest, a stage is a biological phenomenon, the result of some organism cognizing one environment as another environment. Stages, in other words, are not semantic. It is simply the case that beetles sensing environments absent spiders will blunder into trapdoor spiders. It’s simply the case that some birds, sensing chicks, will feed those chicks, even if one of them happens to be a cuckoo. It is simply the case that various organisms exploit the cognitive insensitivities of various other organisms. One need not ascribe anything so arcane as ‘false beliefs’ to birds and beetles to make sense of their exploitation. All they need do is function in a way typically cued by one family of (often happy) environments in a different (often disastrous) environment.

Stages are rife throughout the natural world simply because biological cognition is so expensive. All cognition can be exploited because all cognition is bounded, dependant on taking innumerable factors for granted. Probabilistic guesses have to be made always and everywhere, such are the exigencies of survival and reproduction. Competing species need only happen upon ways to trigger those guesses in environments reproductively advantageous to them, and selection will pace out a new niche, a position in what might be called manipulation space.

The difficulty with qualifying a stage as a biological phenomenon, however, is that I included intentional artifacts such as narratives, paintings, and amusement parks as examples of stages above. The problem with this is that no one knows how to reconcile the biological with the intentional, how to fit meaning into the machinery of life.

And yet, as easy as it is to anthropomorphize the cuckoo’s ‘treachery’ or the trapdoor spider’s ‘cunning’—to infuse our biological examples with meaning—it seems equally easy to ‘zombify’ narrative or painting or Disney World. Hearing the Iliad, for instance, is a prodigious example of staging, insofar as it involves the serial cognition of alternate environments via auditory cues embedded in an actual, but largely neglected, environment. One can easily look at the famed cave paintings of Chauvet, say, as a manipulation of visual cues that automatically triggers the cognition of absent things, in this case, horses:

But if narrative and painting are stages so far as ‘cognizing alternate environments’ goes, the differences between things like the Iliad or Chauvet and things like trapdoor spiders and cuckoos are nothing less than astonishing. For one, the narrative and pictorial cuing of alternative environments is only partial; the ‘alternate environment’ is entertained as opposed to experienced. For another, the staging involved in the former is communicative, whereas the staging involved in the latter is not. Narratives and paintings mean things, they possess ‘symbolic significance,’ or ‘representational content,’ whereas the predatory and parasitic stages you find in the natural world do not. And since meaning resists biological explanation, this strongly suggests that communicative staging resists biological explanation.

But let’s press on, daring theorists that we are, and see how far our ‘zombie stage’ can take us. The fact is, the ‘manipulation space’ intrinsic to bounded cognition affords opportunities as well as threats. In the case of Chauvet, for instance, you can almost feel the wonder of those first artists discovering the relations between technique and visual effect, ways to trick the eye into seeing what was not there there. Various patterns of visual information cue cognitive machinery adapted to solve environments absent those environments. Flat surfaces become windows.

Let’s divvy things up differently, look at cognition and metacognition in terms of multiple channels of information availability versus cognitive capacity. On this account, staging need not be complete: as with Chauvet, the cognition of alternate environments can be partial, localized within the present environment. And as with Chauvet, this embedded staging can be instrumentalized, exploited for various kinds of effects. Just how the cave paintings at Chauvet were used will always be a matter of archaeological speculation, but this in itself tells us something important about the kind of stage we’re now talking about: namely, their specificity. We share the same basic cognitive mechanisms as the original creators and consumers of the Horses, for instance, but we share nothing of their individual histories. This means the stage we step onto encountering them is bound to differ, perhaps radically, from the stage they stepped onto encountering them in the Upper Paleolithic. Since no individuals share precisely the same history, this means that all embedded stages are unique in some respect.

The potential evolutionary value of embedded stages, the kind of ‘cognitive double-vision’ peculiar to humans, seems relatively clear. If you can draw a horse you can show a fellow hunter what to look for, what direction to approach it, where to strike with a spear, how to carve the joints for efficient transportation, and so on. Embedding, in other words, allows organisms to communicate cognitive relationships to actual environments by cuing the cognition of that environment absent that environment. Embedding also allows organisms to communicate cognitive relationships to nonexistent environments as well. If you can draw a cave bear, you can just as easily deceive as teach a potential competitor. And lastly, embedding allows organisms to game their own cognitive systems. By experimenting with patterns of visual information, they can trigger a wide variety of different responses, triggering wonder, lust, fear, amusement, and so on. The cave paintings at Chauvet include what is perhaps the oldest example of pictorial ‘porn’ (in this case, a vulva formed by a bull overlapping a lion) for a reason.

Humans, you could say, are the staging animal, the animal capable of reorganizing and coordinating their cognitive comportments via the manipulation of available information into cues, those patterns prone to trigger various heuristic systems ‘out of school.’ Research into episodic memory reveals an intimate relation between the constructive (as opposed to veridical) nature of episodic memory and the ability to imagine future environments. Apparently the brain does not so much record events as it ransacks them, extracting information strategic to solving future environments. Nothing demonstrates the profound degree to which the brain is invested in strategic staging as the default or task-negative network. Whenever we find ourselves disengaged from some ongoing task, our brains, far from slowing down, switch modes and begin processing alternate, typically social, environments. We ‘daydream,’ or ‘ruminate,’ or ‘fantasize,’ activities almost as metabolically expensive as performing focussed tasks. The resting brain is a staging brain—a story-telling brain. It has literally evolved to cue and manipulate its own cognitive systems, to ‘entertain’ alternate environments, laying down priors in the absence of genuine experience to better manage surprise.

Language looms large over all this, of course, as the staging device par excellence. Language allows us to ‘paint a picture,’ or cue various cognitive systems, at any time. Via language, multiple humans can coordinate their behaviours to provide a single solution; they can engage their environments at ever more strategic joints, intervene in ways that reliably generate advantageous outcomes. Via language, environmental comportments can be compared, tested as embedded stages, which is to say, on the biological cheap. And the list goes on. The upshot is that language, like cave paintings, puts human cognition at the disposal of human cognition…

And—here’s the thing—while remaining utterly blind to the structure and dynamics of human cognition.

The reason for this is simple: the biological complexity required to cognize environments is simply too great to be cognized as environmental. We see the ash and pigment smeared across the stone, we experience (the illusion of) horses, and we have no access whatsoever to the machinery in between. Or to phrase it in zombie terms, humans access environmental information, ash and pigment, which cues cognitive comportments to different environmental information, horses, in the absence of any cognitive comportment to this process. In fact, all we see are horses, effortlessly and automatically; it actually requires effort to see the ash and pigment! The activated environment crowds the actual environment from the focus to the fringe. The machinery that makes all this possible doesn’t so much as dimple the margin. We neglect it. And accordingly, what inklings we have strike us as all there is.

The question of signification is as old as philosophy: how the hell do nonexistent horses leap from patterns of light or sound? Until recently, all attempts to answer this question relied on observations regarding environmental cues, the resulting experience, and the environment cued. The sign, the soul, and the signified anchored our every speculative analysis simply because, short baffling instances of neuropathology, the machinery responsible never showed its hand.

Our cognitive comportment to signification, in other words, looked like:

Which is to say, a stage.

Because we’re quite literally ‘hardwired’ into this position, we have no way of intuiting the radically impoverished (because specialized) nature of the information made available. We cannot trudge on the perpendicular to see what the stage looks like from different angles—we cannot alter our existing cognitive comportments. Thus, what might be called the semiotic stage strikes us as the environment, or anything but a stage. So profound is the illusion that the typical indicators of informatic insufficiency, the inability to leverage systematically effective behaviour, the inability to command consensus, are habitually overlooked by everyone save the ‘folk’ (ironically enough). Sign, soul, and signified could only take us so far. Despite millennia of philosophical and psychological speculation, despite all the myriad regimentations of syntax and semantics, language remains a mystery. Controversy reigns—which is to say, we as yet lack any decisive scientific account of language.

But then science has only begun the long trudge on the perpendicular. The project of accessing and interpreting the vast amounts of information neglected by the semiotic stage is just getting underway.

Since all the various competing semiotic theories are based on functions posited absent any substantial reference to the information neglected, the temptation is to assume that those functions operate autonomously, somehow ‘supervene’ upon the higher dimensional story coming out cognitive neuroscience. This has a number of happy dialectical consequences beyond simply proofing domains against cognitive scientific encroachments. Theoretical constraints can even be mapped backward, with the assumption that neuroscience will vindicate semiotic functions, or that semiotic functions actually help clarify neuroscience. Far from accepting any cognitive scientific constraints, they can assert that at least one of their multiple stabs in the dark pierces the mystery of language in the heart, and is thus implicitly presupposed in all communicative acts. Heady stuff.

Semiotics, in other words, would have you believe that either this

is New York City as we know it, and will be vindicated by the long cognitive neuroscientific trudge on the perpendicular, or that it’s a special kind of New York City, one possessing no perpendicular to trudge—not unlike, surprise-surprise, assumptions regarding the first-person or intentionality in general.

On this account, the functions posited are sometimes predictive, sometimes not, and even when they are predictive (as opposed to merely philosophical), they are clearly heuristic, low-dimensional ways of tracking extremely complicated systems. As such, there’s no reason to think them inexplicably—magically—‘autonomous,’ and good reason to suppose why it might seem that way. Sign, soul, and signified, the blinkered channels that have traditionally informed our understanding of language, appear inviolable precisely because they are blinkered—since we cognize via those channels, the limits of those channels cannot be cognized: the invisibility of the perpendicular becomes its impossibility.

These are precisely the kinds of errors we should expect speaking animals to make in the infancy of their linguistic self-understanding. You might even say that humans were doomed to run afoul ‘theoretical hyperrealities’ like semiotics, discursive Disney Worlds…

Except that in Disney World, of course, the stages are advertised as stages, not inescapable or fundamental environments. Aside from policy level stuff, I have no idea how Disney World or Disney corporation systematically contributes to the subversion of social justice, and neither, I would submit, does any semiotician living. But I do think I know how to fit Disney into a far larger, and far more disturbing set of trends that have seized society more generally. To see this, we have to leave semiotics behind…

May 18, 2015

More Disney than Disney World: Semiotics as Theoretical Make-believe

I: SORCERERS OF THE MAGIC KINGDOM (a.k.a. THE SEMIOTICIAN)

Ask a humanities scholar their opinion of Disney and they will almost certainly give you some version of Louis Marin’s famous “degenerate utopia.”

And perhaps they should. Far from a harmless amusement park, Disney World is a vast commercial enterprise, one possessing, as all corporations must, a predatory market agenda. Disney also happens to be in the meaning business, selling numerous forms of access to their propriety content, to their worlds. Disney (much like myself) is in the alternate reality game. Given their commercial imperatives, their alternate realities primarily appeal to children, who, branded at so young an age, continue to fetishize their products well into adulthood. This generational turnover, combined with the acquisition of more and more properties, assures Disney’s growing cultural dominance. And their messaging is obviously, even painfully, ideological, both escapist and socially conservative, designed to systematically neglect all forms of impersonal conflict.

I think we can all agree on this much. But the humanities scholar typically has something more in mind, a proclivity to interpret Disney and its constituents in semiotic terms, as a ‘veil of signs,’ a consciousness constructing apparatus designed to conceal and legitimize existing power inequities. For them, Disney is not simply apologetic as opposed to critical, it also plays the more sinister role of engendering and reinforcing hyperreality, the seamless integration of simulation and reality into disempowering perspectives on the world.

So as Baudrillard claims in Simulacra and Simulations:

The Disneyland imaginary is neither true nor false: it is a deterrence machine set up in order to rejuvenate in reverse the fiction of the real. Whence the debility, the infantile degeneration of this imaginary. It is meant to be an infantile world, in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the ‘real’ world, and to conceal the fact that the real childishness is everywhere, particularly among those adults who go there to act the child in order to foster illusions of their real childishness.

Baudrillard sees the lesson as an associative one, a matter of training. The more we lard reality with our representations, Baudrillard believes, the greater the violence done. So for him the great sin of Disneyland lay not so much in reinforcing ideological derangements via simulation, but in completing the illusion of an ideologically deranged world. It is the lie within the lie, he would have us believe, that makes the second lie so difficult to see through. The sin here is innocence, the kind of belief that falls out of cognitive incapacity. Why do kids believe in magic? Arguably, because they don’t know any better. By providing adults a venue for their children to believe, Disney has also provided them evidence of their own adulthood. Seeing through Disney’s simulations generates the sense of seeing through all illusions, and therefore, seeing the real.

Disney, in other words, facilitates ‘hyperreality’—a semiotic form of cognitive closure—by rendering consumers blind to their blindness. Disney, on the semiotic account, is an ideological neglect machine. Its primary social function is to provide cognitive anaesthesia to the masses, to keep them as docile and distracted as possible. Let’s call this the ‘Disney function,’ or Df. For humanities scholars, as a rule, Df amounts to the production of hyperreality, the politically pernicious conflation of simulation and reality.

In what follows, I hope to demonstrate what might seem a preposterous figure/field inversion. What I want to argue is that the semiotician has Df all wrong—Disney is actually a far more complicated beast—and that the production of hyperreality, if anything, belongs to his or her own interpretative practice. My claim, in other words, is that the ‘politically pernicious conflation of simulation and reality’ far better describes the social function of semiotics than it does Disney.

Semiotics, I want to suggest, has managed to gull intellectuals into actively alienating the very culture they would reform, leading to the degeneration of social criticism into various forms of moral entertainment, a way for jargon-defined ingroups to transform interpretative expertise into demonstrations of manifest moral superiority. Piety, in effect. Semiotics, the study of signs in life, allows the humanities scholar to sit in judgment not just of books, but of text,* which is to say, the entire world of meaning. It constitutes what might be called an ideological Disney World, only one that, unlike the real Disney World, cannot be distinguished from the real.

I know from experience the kind of incredulity these kinds of claim provoke from the semiotically minded. The illusion, as I know first-hand, is that complete. So let me invoke, for the benefit of those smirking down at these words, the same critical thinking mantra you train into your students, and remind you that all institutions are self-regarding, all institutions cultivate congratulatory myths, and to suggest that the notion of some institution set apart, some specialized cabal possessing practices inoculated against the universal human assumption of moral superiority, is implausible through and through. Or at least worth suspicion.

You are almost certainly deluded in some respect. What follows merely illustrates how. Nothing magical protects you from running afoul your cognitive shortcomings the same as the rest of humanity. As such, it really could be the case that you are the more egregious sorcerer, and that your world-view is the real ‘magic kingdom.’ If this idea truly is as preposterous as it feels, then you should have little difficulty understanding it on its own terms, and dismantling it accordingly.

.

II: INVESTIGATING THE CRIME SCENE

Sign and signified, simulation and simulated, appearance and reality: these dichotomies provide the implicit conceptual keel for all ideologically motivated semiotic readings of culture. This instantly transforms Disney, a global industrial enterprise devoted to the production of alternate realities, into a paradigmatic case. The Walt Disney Corporation, as fairly every child in the world knows, is in the simulation business. Of course, this alone does not make Disney ‘bad.’ As an expert interpreter of signs and simulations, the semiotician has no problem with deviations from reality in general, only those deviations prone to facilitate particular vested interests. This is the sense in which the semiotic project is continuous with the Enlightenment project more generally. It presumes that knowledge sets us free. Semioticians hold that some appearances—typically those canonized as ‘art’—actually provide knowledge of the real, whereas other appearances serve only to obscure the real, and so disempower those who run afoul them.

The sin of the Walt Disney Corporation, then, isn’t that it sells simulations, it’s that it sells disempowering simulations. The problem that Disney poses the semiotician, however, is that it sells simulations as simulations, not simulations as reality. The problem, in other words, is that Disney complicates their foundational dichotomy, and in ways that are not immediately clear.

You see microcosms of this complication everywhere you go in Disney World, especially where construction or any other ‘illusion dispelling’ activities are involved. Sights such as this:

where pre-existing views are laminated across tarps meant to conceal some machination that Disney would rather not have you see, struck me as particularly bizarre. Who is being fooled here? My five year old even asked why they would bother painting trees rather than planting them. Who knows, I told her. Maybe they were planting trees. Maybe they were building trees such as this:

Everywhere you go you stumble across premeditated visual obstructions, or the famous, omnipresent gates labelled ‘CAST MEMBERS ONLY.’ Everywhere you go, in other words, you are confronted with obvious evidence of staging, or what might be called premeditated information environments. As any magician knows, the only way to astound the audience is to meticulously control the information they do and do not have available. So long as absolute control remains technically infeasible, they often fudge, relying on the audience’s desire to be astounded to grease the wheels of their machinations.

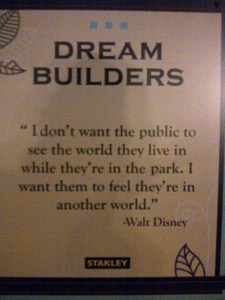

One finds Disney’s commitment to the staging credo tacked here and there across the very walls raised to enforce it:

Walt Disney was committed to the notion of environmental immersion, with the construction of ‘stages’ that were good enough, given various technical and economic limitations, to kindle wonder in children and generosity in their parents. Almost nobody is fooled outright, least of all the children. But most everyone is fooled enough. And this is the only thing that matters, when any showman tallies their receipts at the end of the day: staging sufficiency, not perfection. The visibility of artifice will be forgiven, even revelled in, so long as the trick manages to carry the day…

No one knows this better than the cartoonist.

The ‘Disney imaginary,’ as Baudrillard calls it, is first and foremost a money making machine. For parents of limited means, the mechanical regularity with which Disney has you reaching for your wallet is proof positive that you are plugged into some kind of vast economic machine. And making money, it turns out, doesn’t require believing, it requires believing enough—which is to say, make-believe. Disney World can revel in its artificiality because artificiality, far from threatening the primary function of the system, actually facilitates it. Children want cartoons; they genuinely prefer low-dimensional distortions of reality over reality. Disney is where cartoons become flesh and blood, where high dimension replicas of low-dimension constructs are staged as the higher dimensional truth of those constructs. You stand in line to have your picture taken with a phoney Tinkerbell that you say is real to play this extraordinary game of make-believe with your children.

To the extent that make-believe is celebrated, the illusion is celebrated as benign deception. You walk into streets like this:

that become this:

as you trudge from the perpendicular. The staged nature of the stage is itself staged within the stage as something staged. This is the structure of the Indiana Jones Stunt Spectacular, for instance, where the audience is actually transformed into a performer on a stage staged as a stage (a movie shoot). At every turn, in fact, families are confronted with this continual underdetermination of the boundaries between ‘real’ and not ‘real.’ We watched a cartoon Crush (the surfer turtle from Finding Nemo) do an audience interaction comedy routine (we nearly pissed ourselves). We had a bug jump out of the screen and spray us with acid (water) beneath that big ass tree above (we laughed and screamed). We were skunked twice. The list goes on and on.

All these ‘attractions’ both celebrate and exploit the narrative instinct to believe, the willingness to overlook all the discrepancies between the fantastic and the real. No one is drugged and plugged into the Disney Matrix against their will; people pay, people who generally make far less than tenured academics, to play make-believe with their children.

So what are we to make of this peculiar articulation of simulations and realities? What does it tell us about Df?

The semiotic pessimist, like Baudrillard, would say that Disney is subverting your ability to reliably distinguish the real from the not real, rendering you a willing consumer of a fictional reality filled with fictional wars. Umberto Eco, on the other hand, suggests the problem is one of conditioning consumer desire. By celebrating the unreality of the real, Disney is telling “us that faked nature corresponds much more to our daydream demands” (Travels in Hyperreality, 44). Disney, on his account, whets the wrong appetite. For both, Disney is both instrumental to and symptomatic of our ideological captivity.

The optimist, on the other hand, would say they’re illuminating the contingency of the real (a.k.a. the ‘power of imagination’), training the young to never quite believe their eyes. On this view, Disney is both instrumental to and symptomatic of our semantic creativity (even as it ruthlessly polices its own intellectual properties). According to the apocryphal quote often attributed to Walt Disney, “If you can dream it, you can do it.”

This is the interpretative antinomy that hounds all semiotic readings of the ‘Disney function.’ The problem, put simply, is that interpretations falling out of the semiotic focus on sign and signified, simulation and simulated, cannot decisively resolve whether self-conscious simulation a la Disney serves, in balance, more to subvert or to conserve prevailing social inequities.