R. Scott Bakker's Blog, page 23

May 11, 2013

Dodging the Agent, Tripping into the Swarm

Aphorism of the Day: Whether a question is yummy or yucky usually depends on which way it’s aimed – unlike a lollipop.

[Terrence Blake has been asking some hard questions about BBT over at his blog, Agent Swarm. The following is my reply to "Bakker's BBT (3): The Spectre of Eliminativism" which I thought, given the eye-crossing nature of the two previous posts, might be worthwhile pasting unedited as a post here.]

.

Okay, I think I’m finally getting a handle on why we’ve been at cross-purposes. BBT has some very peculiar, very counterintuitive epistemological consequences, which are impractical to raise every time I discuss the theory. For one, it does away with binaries like ‘truth versus illusion,’ ‘fact versus fiction,’ replacing them instead with a continuum of mechanical effectivities. As it stands, however, I get roundly and regularly criticized for being too technical (too reliant on conceptual neologisms) and too obscure (too apt to dive into the inside-out counterintuitivities), so I adopt the standard parlance where it seems to suffice to get my point across. I try to be careful, try to insert qualifying phrases like ‘Taking the mechanistic paradigm of the life sciences as our cognitive baseline,’ but as I’m sure you’re aware, Terrence, writing blog entries has a dialogic character to it, and you get so you think you don’t need to append such operators–take them as given. But it’s clearly caused some difficulties here.

I just want to say, I appreciate the frustrations, and I understand the suspicion that I’m simply using this as a dodge. All I can say is that this is not *consciously* the case! And I assure you I’m not saying anything here that I have explicitly stated elsewhere. So with this in ‘mind,’ onto your questions:

“The question amounts to : is your BBT a useful heuristic that can guide and explicate philosophical and scientific research or is it a new apodictic foundation, unrevisable in its basic structure?”

It’s heuristic. Like all theory.

“So my question is pluralist: does Bakker admit the value of other quite different approaches that aim at being “continuous with the natural sciences” such as for example Bruno Latour’s or François Laruelle’s? If yes, then great as he is maintaining his pluralism and applying it to himself. If no, then I fear his baby is not only drowning in metaphysical bathwater, it is dissolving in it. Which would be regrettable.”

I read some Latour back in the nineties, but really have no idea what his position amounts to. Laruelle and nonphilosophy, I find deeply interesting. If BBT is scientifically confirmed, then both positions will be scientifically discontinuous the degree to which they embrace intentionality. As it stands, it’s just a hypothetical posit, one that has been tyrannizing my philosophical imagination because of the parsimonious way it seems to dissolve a number of traditional problems, and because of the unexplored vista of ‘post-intentional’ philosophy it seems to open up.

“Bakker is a novelist, and so it should be evident to him too. Yet he persists in affirming the ideal of scientific imperialism (which is not at all science!) that all “good” cognition ( called “knowledge” in other modes of life) is science. I like his work and I am trying to find a “diplomatic” (in Bruno Latour’s sense) way of getting him to include his own writing practice in his image of knowledge, and so to pluralise him a little more.”

But this is precisely the thing I don’t affirm! Scientific cognition *is imperialistic* as a matter of historical fact. I finally realized that you’ve been reading my descriptive claims of what science does when it infiltrates a domain as normative. I’m just saying this is what has historically happened, and no one has yet given me a plausible argument as to why any traditional form of cognizing will prove resistant. So, for instance, I think it is likely inevitable that science and technology will continue driving more and more cultural content (computers already write articles and novels), until the notion of ‘fiction writing’ as a ‘traditional artform’ will have the same condescending twang as ‘traditional crafts.’ And I think this an almost unimaginable tragedy.

So here’s a question: As a pluralist, do you affirm the cognitive status of things like geomancy, fundamental christianity, astrology, or phrenology?

Here’s the thing. I do. Why? Because cognition in its most general sense is about problem-solving, and all these things are capable of solving certain problems in certain problem ecologies. Are any of these things ‘accurate’? Not at all. They are exceedingly low dimensional. Phrenology was a great way to relieve people of their money, but a horrible way to understand human beings. It was subreptive, a way to solve one problem while appearing to solve another.

BBT says that something similar is going on with metacognition.

So, it takes the mechanistic paradigm of the life sciences as its baseline for ‘accurate’ or high-dimensional cognition. Of course this baseline is contingent. The question I ask, is what else is there? At this time in history, what other species of cognition gives us anything remotely resembling the high-dimensional problem-solving ability of the sciences?

I certainly don’t know, and I’ve arguing and asking this question for a long time (ever since reading Negative Dialectics in the 90s, in fact). And given that our economic system is designed to lavish obscene rewards on problem-solving, I think what I call Akratic Society is pretty much inevitable. I fear BBT may be confirmed (because of its parsimony and comprehensiveness), but even if it lands in the dustbin, I think it’s inevitable that philosophy will be snapped if half, into a subdiscipline of cognitive neuropsychology on the one side, and into New Age fluff on the other.

That’s another depressing upshot I would love to be argued out of. But I fear, short of Adorno’s Messianic moment or Heidegger’s God, we are well and truly screwed. Put another way, Only heuristic X can save us now!

May 9, 2013

The Violence of Representation

There are no representations, only recapitulations of environmental structure adapted to various functions. On BBT, ‘representation’ is an artifact of medial neglect, the fact that the brain, as a part of the environment, cannot include itself in its environmental models. All the medial complexities responsible for cognition are occluded, and therefore must be metacognized in low-dimensional effective as opposed to high-dimensional accurate terms. Recapitulations thus seem to hang in a noncausal void yet nevertheless remain systematically related to external environments. ‘Aboutness’ heuristically captures the relation, and ‘truth’ the systematicity. Mechanical recapitulations of structure are thus transformed into ‘representations,’ which are then taken to be universal, so generating all the difficulties that arise when heuristics find themselves deployed outside the appropriate problem ecology.

We are all systems embedded in systems, worms in the wool. We are all components. And this, as it so happens, is precisely the way science views us. The so-called ‘violence of representation,’ as the continental tradition has it, primarily consists in the occlusion of the mechanical (as opposed to practical) systematicity that binds all cognition to what is cognized. The ‘violence,’ in effect, is a product of medial neglect and the resulting metacognitive illusions that lead to the presumption of representation in the first place.

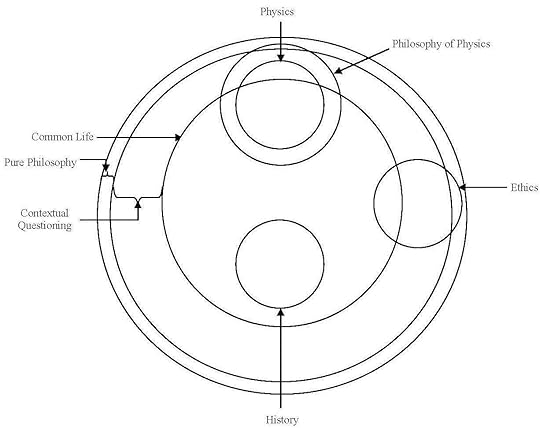

To lay it out visually, consider the following:

To the left we have the brain as a worm in the wool, as an environmental component that is causally sensitive, either actually or potentially, to a great number of other environmental components. These causal relations (represented by the light grey lines) are medial insofar as they enable the neural recapitulation of other causal relations (represented by the dark grey lines) extant in the environment.

To the left we have the brain as a worm in the wool, as an environmental component that is causally sensitive, either actually or potentially, to a great number of other environmental components. These causal relations (represented by the light grey lines) are medial insofar as they enable the neural recapitulation of other causal relations (represented by the dark grey lines) extant in the environment.

To the right we have that brain’s ‘component perspective,’ what it can cognize (or metacognize of that cognition) of the environment as a component within that environment. All medial causal relations are occluded, given that the brain possesses no ‘meta medial’ means of recapitulating them. With the occlusion of medial causal relations comes the occlusion of componency: the brain cannot accurately recapitulate its functions, either relative to itself, or relative to the greater mechanism of its environment. Thus the asymptotic margin, the fact that recapitulations simply ‘hang in oblivion,’ as it were. What is not recapitulated in a given brain simply does not exist that for that brain. Since only a finite amount can be recapitulated (and integrated into conscious cognition and experience), what is recapitulated cannot be embedded within a greater network of recapitulations, and so ‘hangs,’ paradoxically finite and yet unbounded.

The brain is a component that cannot accurately cognize itself as such. Conscious cognition and experience recapitulate lateral structure and function while neglecting medial structure and function. Reflection (deliberative theoretical metacognition) thus seems to reveal acomponential entities, asymptotic recapitulations of lateral structure and function absent any of the medial intricacies responsible–or what are commonly called ‘mental representations,’ entities possessing intentional and logical relations to the greater environment.

Here we see the power of the third-person, or the ‘view from nowhere.’ Medial machinery can recapitulate the causal continuity of lateral environments, but only at the cost of neglecting the continuities that make that recapitulation possible. The neural problem of ‘understanding’ a given environmental system is simply the problem of occupying the most adaptive mechanical position relative to that system within the causal totality of the greater environment. A position counts as ‘most adaptive’ when information accumulation becomes maladaptive–a waste of resources, in effect. But this relational ‘sweet spot,’ which is entirely due to the occupation of a determinate relational position within the causal totality, cannot be (readily) cognized as such given medial neglect. The brain can learn (via trial and error) that a particular recapitulation is optimally effective even though the how remains perpetually occluded. Deemed reliable, such recapitulations are inventoried as specialized cogs for specific mechanistic circumstance. Given medial neglect, however, metacognition is utterly blind to this dimension. Circumstance and what metacognition has misconstrued as mental representation hang together as if by magic. The informatic constraints pertaining to a given ‘view’ or ‘perspective’ no longer apply. This ‘anywhereness’ dovetails with the apparent ‘from nowhereness’ pertaining to asymptosis.

We presume truth. Since the whole system is tuned to mechanically maximize mechanical reliability, truth naturally seems to be the primary function of mental representations. What is perhaps the greatest dead end in the history of human inquiry is born of apparent intuitive verities stemming from medial neglect.

April 29, 2013

The Crux

Aphorism of the Day: Give me an eye blind enough, and I will transform guttering candles into exploding stars.

.

The Blind Brain Theory turns on the following four basic claims:

1) Cognition is heuristic all the way down.

2) Metacognition is continuous with cognition.

3) Metacognitive intuitions are the artifact of severe informatic and heuristic constraints. Metacognitive accuracy is impossible.

4) Metacognitive intuitions only loosely constrain neural fact. There are far more ways for neural facts to contradict our metacognitive intuitions than otherwise.

A good friend of mine, Dan Mellamphy, has agreed to go through a number of the posts from the past eighteen months with an eye to pulling them together into a book of some kind. I’m actually thinking of calling it Through the Brain Darkly: because of Neuropath, because the blog is called Three Pound Brain, and because of my apparent inability to abandon the tedious metaphorics of neural blindness. Either way, I thought boiling BBT down to its central commitments would be worthwhile exercise. Like a picture taken on a rare, good hair day…

.

1) Cognition is heuristic all the way down.

I take this claim to be trivial. Heuristics are problem-solving mechanisms that minimize computational costs via the neglect of extraneous or inaccessible information. The human brain is itself a compound heuristic device, one possessing a plurality of cognitive tools (innate and learned component heuristics) adapted to a broad but finite range of environmental problems. The human brain, therefore, possesses a ‘compound problem ecology’ consisting of the range of those problems primarily responsible for driving its evolution, whatever they may be. Component heuristics likewise possess problem ecologies, or ‘scopes of application.’

.

2) Metacognition is continuous with cognition.

I also take this claim to be trivial. The most pervasive problem (or reproductive obstacle) faced by the human brain is the inverse problem. Inverse problems involve deriving effective information (ie., mass and trajectory) from some unknown, distal phenomenon (ie., a falling tree) via proximal information (ie., retinal stimuli) possessing systematic causal relations (ie., reflected light) to that phenomenon. Hearing, for instance, requires deriving distal causal structures, an approaching car, say, on the basis of proximal effects, the cochlear signals triggered by the sound emitted from the car. Numerous detection technologies (sonar, radar, fMRI, and so on) operate on this very principle, determining the properties of unknown objects from the properties of some signal connected to them.

The brain can mechanically engage its environment because it is mechanically embedded in its environment–because it is, quite literally, just more environment. The brain is that part of the environment that models/exploits the rest of the environment. Thus the crucial distinction between those medial environmental components involved in modelling/enacting (sensory media, neural mechanisms) and those lateral environmental components modelled. And thus, medial neglect, the general blindness of the human brain to its own structure and function, and its corollary, lateral sensitivity, the general responsiveness of the brain to the structure and function of its external environments–or in other words, the primary problem ecology of the heuristic brain.

Medial neglect and lateral sensitivity speak to a profound connection between ignorance and knowledge, how sensitivity to distal, lateral complexities necessitates insensitivity to proximal, medial complexities. Modelling environments necessarily exacts what might be called an ‘autoepistemic toll’ on the systems responsible. The greater the lateral fidelity, the more sophisticated the mechanisms, the greater the surplus of ‘blind,’ or medial, complexity. The brain, you could say, is an organ that transforms ‘risky complexity’ into ‘safe complexity,’ that solves distal unknowns that kill by accumulating proximal unknowns (neural mechanisms) that must be fed.

The parsing of the environment into medial and lateral components represents more a twist than a scission: the environment remains one environment. Information pertaining to brain function is environmental information, which is to say, information pertinent to the solution of potential environmental problems. Thus metacognition, heuristics that access information pertaining to the brain’s own operations.

Since metacognition is continuous with cognition, another part of the environment engaged in problem solving the environment, it amounts to the adaptation of neural mechanisms sensitive in effective ways to other neural mechanisms in the brain. The brain, in other words, poses an inverse problem for itself.

.

3) Metacognitive intuitions are the artifact of severe informatic and heuristic constraints. Metacognitive accuracy is impossible.

This claim, which is far more controversial than those above, directly follows from the continuity of metacognition and cognition–from the fact that the brain itself constitutes an inverse problem. This is because, as an inverse problem, the brain is quite clearly insoluble. Two considerations in particular make this clear:

1) Target complexity: The human brain is the most complicated mechanism known. Even as an external environmental problem, it has taken science centuries to accumulate the techniques, information, and technology required to merely begin the process of providing any comprehensive mechanistic explanation.

2) Target complicity: The continuity of metacognition and cognition allows us to see that the structural entanglement of metacognitive neural mechanisms with the neural mechanisms tracked, far from providing any cognitive advantage, thoroughly complicates the ability of the former to derive high-dimensional information from the latter. One might analogize the dilemma in terms of two biologists studying bonobos, the one by observing them in their natural habitat, the other by being sewn into a burlap sack with one. Relational distance and variability provide the biologist-in-the-habitat quantities and kinds (dimensions) of information simply not available to the biologist-in-the-sack. Perhaps more importantly, they allow the former to cognize the bonobos without the complication of observer effects. Neural mechanisms sensitive to other neural mechanisms* access information via dedicated, as opposed to variable, channels, and as such are entirely ‘captive’: they cannot pursue the kinds of active environmental engagement that permit the kind of high-dimensional tracking/modelling characteristic of cognition proper.

Target complexity and complicity mean that metacognition is almost certainly restricted to partial, low-dimensional information. There is quite literally no way for the brain to cognize itself as a brain–which is to say, accurately. Thus the mind-body problem. And thus a good number of the perennial problems that have plagued philosophy of mind and philosophy more generally (which can be parsimoniously explained away as different consequences of informatic privation). Heuristic problem-solving does not require the high-dimensional fidelity that characterizes our sensory experience of the world, as simpler life forms show. The metacognitive capacities of the human brain turn on effective information, scraps gleaned via adventitious mutations that historically provided some indeterminate reproductive advantage in some indeterminate context. It confuses these scraps for wholes–suffers the cognitive illusion of sufficiency–simply because it has no way of cognizing its informatic straits as such. Because of this, it perpetually mistakes what could be peripheral fragments in neurofunctional terms, for the entirety and the crux.

.

4) Metacognitive intuitions only loosely constrain neural fact. There are far more ways for neural facts to contradict our metacognitive intuitions than otherwise.

Given the above, the degree to which the mind is dissimilar to the brain is the degree to which deliberative metacognition is simply mistaken. The futility of philosophy is no accident on this account. When we ‘reflect upon’ conscious cognition or experience, we are accessing low-dimensional information adapted to metacognitive heuristics adapted to narrow problem ecologies faced by our preliterate–prephilosophical–ancestors. Thanks to medial neglect, we are utterly blind to the actual neurofunctional context of the information expressed in experience. Likewise, we have no intuitive inkling of the metacognitive apparatuses at work, no idea whether they are many as opposed to one, let alone whether they are at all applicable to the problem they have been tasked to solve. Unless, that is, the task requires accuracy–getting some theoretical metacognitive account of mind or meaning or morality or phenomenology right–in which case we have good grounds (all our manifest intuitions to the contrary) to assume that such theoretical problem ecologies are hopelessly out of reach.

Experience, the very sum of significance, is a kind of cartoon that we are. Metacognition assumes the mythical accuracy (as opposed to the situation-specific efficacy) of the cartoon simply because that cartoon is all there is, all there ever has been. It assumes sufficiency because, in other words, cognizing its myriad limits and insufficiencies requires access to information that simply does not exist for metacognition.

The metacognitive illusion of sufficiency means that the dissociation between our metacognitive intuition of function and actual neural function can be near complete, that memory need not be veridical, the feeling of willing need not be efficacious, self-identity need not be a ‘condition of possibility,’ and so on, and so on. It means, in other words, that what we call ‘experience’ can be subreptive through and through, and still seem the very foundation of the possibility of knowledge.

It means that, all things being equal, the thoroughgoing neuroscientific overthrow our manifest self-understanding is far, far more likely than even its marginal confirmation.

April 17, 2013

Lamps Instead of Ladies: The Hard Problem Explained

This is another repost, this one from 2012/07/04. I like it I think because of the way it makes the informatic stakes of the hard problem so vivid. I do have some new posts in the works, but Golgotterath has been gobbling up more and more of my creative energy of late. For those of you sending off-topic comments asking about a publication date for The Unholy Consult, all I can do is repeat what I’ve been saying for quite some time now: You’ll know when I know! The book is pretty much writing itself through me at this point, and from the standpoint of making good on the promise of this series, I think this is far and away the best way to proceed. It will be done when it tells me it’s done. I would rather frustrate you all with an extended wait than betray the series. If you want me to write faster, cut me cheques, shame illegal downloaders, or simply thump the tub as loud as you can online and in print. So long as The Second Apocalypse remains a cult enterprise, I simply have to continue working on completing my PhD.

.

The so-called “hard problem” is generally understood as the problem consciousness researchers face closing Joseph Levine’s “explanatory gap,” the question of how mere physical systems can generate conscious experience. The problem is that, as Descartes noted centuries ago, consciousness is so damned peculiar when compared to the natural world that it reveals. On the one hand you have qualia, or the raw feel, the ‘what-it-is-like’ of conscious experiences. How could meat generate such bizarre things? On the other hand you have intentionality, the aboutness of consciousness, as well as the related structural staples of the mental, the normative and the purposive.

In one sense, my position is a mainstream one: consciousness is another natural phenomena that will be explained naturalistically. But it is not just another natural phenomenon: it is the natural phenonmenon that is attempting to explain itself naturalistically. And this is where the problem becomes an epistemological nightmare – or very, very hard.

This is why I espouse what might be called a “Dual Explanation Account of Consciousness.” Any one of the myriad theories of consciousness out there could be entirely correct, but we will never know this because we disagree about just what must be explained for an explanation of consciousness to count as ‘adequate.’ The Blind Brain Theory explains the hardness of the hard problem in terms of the information we should expect the conscious systems of the brain to lack. The consciousness we think we cognize, I want to argue, is the product of a variety of ‘natural anosognosias.’ The reason everyone seems to be barking up the wrong explanatory tree is simply that we don’t have the consciousness we think we do.

Personally, I’m convinced this has to be case to some degree. Let’s call the cognitive system involved in natural explanation the ‘NE system.’ The NE system, we might suppose, originally evolved to cognize external environments: this is what it does best. (We can think of scientific explanation as a ‘training up’ of this system, pressing it to its peak performance). At some point, the human brain found it more and more reproductively efficacious to cognize onboard information – data from itself – as well. In addition to continually sampling and updating environmental information, it began doing the same with its own neural information.

Now if this marks the genesis of human self-consciousness, the confusions we collectively call the ‘hard problem’ become the very thing we should expect. We have an NE system exquisitely adapted over hundreds of millions of years to cognize environmental information suddenly forced to cognize 1) the most complicated machinery we know of in the universe (itself); 2) from a fixed (hardwired) ‘perspective’; and 3) with nary more than a million years of evolutionary tuning.

Given this (and it seems fairly airtight to me), we should expect that the NE system would have enormous difficulty cognizing consciously available information. (1) suggests that the information gleaned will be drastically fractional. (2) suggests that the information accessed will be thoroughly parochial, but also, entirely ‘sufficient,’ given the NE’s rank inability to ‘take another perspective’ relative the gut brain the way it can relative its external environments. (3) suggests the information provided will be haphazard and distorted, the product of kluge-type mutations. [See "Reengineering Dennett" for a more recent consideration of this in terms of 'dimensionality.']

In other words, (1) implies ‘depletion,’ (2) implies ‘truncation’ (since we can’t access the causal provenance of what we access), and (3) implies a motley of distortions. Your NE is quite literally restricted to informatic scraps.

This is the point I keep hammering in my discussions with consciousness researchers: our attempts to cognize experience utilize the same machinery that we use to cognize our environments – evolution is too fond of ‘twofers’ to assume otherwise, too cheap. Given this, the “hard problem” not only begins to seem inevitable, but something that probably every other biologically conscious species in the universe suffers. The million dollar question is this: If information privation generates confusion and illusion regarding phenomena within consciousness, why should it not generate confusion and illusion when regarding consciousness itself?

Think of the myriad mistakes the brain makes: just recently, while partying with my brother-in-law on the front porch, we became convinced that my neighbour from across the street was standing at her window glaring at us – I mean, convinced. It wasn’t until I walked up to her house to ask whether we were being too noisy (or noisome!) that I realized it was her lamp glaring at us (it never liked us anyway), that it was a kooky effect of light and curtains. What I’m saying is that peering at consciousness is no different than peering at my neighbour’s window, except that we are wired to the porch, and so have no way of seeing lamps instead of ladies. Whether we are deliberating over consicousness or deliberating over neighbours, we are limited to the same cognitive systems. As such, it simply follows that the kinds of distortions information privation causes in the one also pertain to the other. It only seems otherwise with consciousness because we are hardwired to the neural porch and have no way of taking a different informatic perspective. And so, for us, it just is the neighbour lady glaring at you through the window, even though it’s not.

Before we can begin explaining consciousness, we have to understand the severity of our informatic straits. We’re stranded: both with the patchy, parochial neural information provided, and with our ancient, environmentally oriented cognitive systems. The result is what we call ‘consciousness.’

The argument in sum is pretty damn strong: Consciousness (as it is) evolved on the back of existing, environmentally oriented cognitive systems. Therefore, we should assume that the kinds of information privation effects pertaining to environmental cognition also apply to our attempts to cognize consciousness. (1), (2), and (3) give us good reason to assume that consciousness suffers radical information privation. Therefore, odds are we’re mistaking a good number of lamps for ladies – that consciousness is literally not what we think it is.

Given the breathtaking explanatory successes of the natural sciences, then, it stands to reason that our gut antipathy to naturalistic explanations of consciousness are primarily an artifact of our ‘brain blindess.’

What we are trying to explain, in effect, is information that has to be depleted, truncated, and distorted – a lady that quite literally does not exist. And so when science rattles on about ‘lamps,’ we wave our hands and cry, “No-no-no! It’s the lady I’m talking about.”

Now I think this is a pretty novel, robust, and nifty dissection of the Hard Problem. Has anyone encountered anything similar anywhere? Does anyone see any obvious assumptive or inferential flaws?

April 13, 2013

Less Human than Human: The Cyborg Fantasy versus the Neuroscientific Real (2012/10/29)

Since Massimo Pigluicci has reposted Julia Galef’s tepid defense of transhumanism from a couple years back, I thought I would repost the critique I gave last fall, an argument which actually turns Galef’s charge of ‘essentialism’ against transhumanism. Short of some global catastrophe, transhumanism is coming (for those who can afford it, at least) whether we want it to or not. My argument is simply that transhumanists need to recognize that the very values they use to motivate their position are likely among the things our posthuman descendents will leave behind.

.

When alien archaeologists sift through the rubble of our society, which public message, out of all those they unearth, will be the far and away most common?

The answer to this question is painfully obvious–when you hear it, that is. Otherwise, it’s one of those things that is almost too obvious to be seen.

Sale… Sale–or some version of it. On sale. For sale. 10% off. 50% off. Bigger savings. Liquidation event!

Or, in other words, more for less.

Consumer society is far too complicated to be captured in any single phrase, but you could argue that no phrase better epitomizes its mangled essence. More for less. More for less. More for less.

Me-me-more-more-me-me-more-arrrrrgh!

Thus the intuitive resonance of “More Human than Human,” the infamous tagline of the Tyrell Corporation, or even ‘transhumanism’ more generally, which has been vigorously rebranding itself the past several months as ‘H+,’ an abbreviation of ‘Humanity plus.’

What I want to do is drop a few rocks into the hungry woodchipper of transhumanist enthusiasm. Transhumanism has no shortage of critics, but given a potent brand and some savvy marketing, it’s hard not to imagine the movement growing by leaps and bounds in the near future. And in all the argument back and forth, no one I know of (with the exception of David Roden, whose book I eagerly anticipate) has really paused to consider what I think is the most important issue of all. So what I want to do is isolate a single, straightforward question, one which the transhumanist has to be able to answer to anchor their claims in anything resembling rational discourse (exuberant discourse is a different story). The idea, quite simply, is to force them to hold the fingers they have crossed plain for everyone to see, because the fact is, the intelligibility of their entire program depends on research that is only just getting under way.

I think I can best sum up my position by quoting the philosopher Andy Clark, one the world’s foremost theorists of consciousness and cognition, who after considering competing visions of our technological future, good and bad, writes, “Which vision will prove the most accurate depends, to some extent, on the technologies themselves, but it depends also–and crucially–upon a sensitive appreciation of our own nature” (Natural-Born Cyborgs, 173). It’s this latter condition, the ‘sensitive appreciation of our own nature,’ that is my concern, if only because this is precisely what I think Clark and just about everyone else fails to do.

First, we need to get clear on just how radical the human future has become. We can talk about the singularity, the transformative potential of nano-bio-info-technology, but it serves to look back as well, to consider what was arguably humanity’s last great break with its past, what I will here call the ‘Old Enlightenment.’ Even though no social historical moment so profound or complicated can be easily summarized, the following opening passage, taken from a 1784 essay called, “An Answer to the Question: ‘What is Enlightenment?’” by Immanuel Kant, is the one scholars are most inclined to cite:

“Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own reason without the guidance of another. This immaturity is self-incurred if its cause is not lack of understanding, but lack of resolution and courage to use it without the guidance of another. The motto of the enlightenment is therefore: Sapere aude! Have courage to use your own understanding!” (“An Answer to the Question: ‘What is Enlightenment?’” 54)

Now how modern is this? For my own part, I can’t count all the sales pitches this resonates with, especially when it comes to that greatest of contradictions, the television commercial. What is Enlightenment? Freedom, Kant says. Autonomy, not from the political apparatus of the state (he was a subject of Frederick the Great, after all), but from the authority of traditional thought–from our ideological inheritance. More new. Less old. New good. Old bad. Or in other words, More better, less worse. The project of the Enlightenment, according to Kant, lies in the maximization of intellectual and moral freedom, which is to say, the repudiation of what we were and an openness to what we might become. Or, as we still habitually refer to it, ‘Progress.’ The Old Enlightenment effectively rebranded humanity as a work in progress, something that could be improved–enhanced–through various forms of social and personal investment. We even have a name for it, nowadays: ‘human capital.’

The transhumanists, in a sense, are offering nothing new in promising the new. And this is more than just ironic. Why? Because even though the Old Enlightenment was much less transformative socially and technologically than the New will almost certainly be, the transhumanists nevertheless assume that it was far more transformative ideologically. They assume, in other words, that the New Enlightenment will be more or less conceptually continuous with the Old. Where the Old Enlightenment offered freedom from our ideological inheritance, but left us trapped in our bodies, the New Enlightenment is offering freedom from our biological inheritance–while leaving our belief systems largely intact. They assume, quite literally, that technology will deliver more of what we want physically, not ideologically.

More better…

Of course, everything hinges upon the ‘better,’ here. More is not a good in and of itself. Things like more flooding, more tequila, or more herpes, just for instance, plainly count as more worse (although, if the tequila is Patron, you might argue otherwise). What this means is that the concept of human value plays a profound role in any assessment of our posthuman future. So in the now canonical paper, “Transhumanist Values,” Nick Bostrom, the Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, enumerates the principle values of the transhumanist movement, and the reasons why they should be embraced. He even goes so far as to provide a wish list, an inventory of all the ways we can be ‘more human than human’–though he seems to prefer the term ‘enhanced.’ “The limitations of the human mode of being are so pervasive and familiar,” he writes, “that we often fail to notice them, and to question them requires manifesting an almost childlike naiveté.” And so he gives us a shopping list of our various incapacities: lifespan; intellectual capacity; body functionality; sensory modalities, special faculties and sensibilities; mood, energy, and self-control. He characterizes each of these categories as constraints, biological limits that effectively prevent us from reaching our true potential. He even provides a nifty little graph to visualize all that ‘more better’ out there, hanging like ripe fruit in the garden of our future, just waiting to be plucked, if only–as Kant would say–we possess the courage.

As a philosopher, he’s too sophisticated to assume that this biological emancipation will simply spring from the waxed loins of unfettered markets or any such nonsense. He fully expects humanity to be tested by this transformation–”[t]ranshumanism,” as he writes, “does not entail technological optimism”–so he offers transhumanism as a kind of moral beacon, a star that can safely lead us across the tumultuous waters of technological transformation to the land of More-most-better–or as he explicitly calls it elsewhere, Utopia.

And to his credit, he realizes that value itself is in play, such is the profundity of the transformation. But for reasons he never makes entirely clear, he doesn’t see this as a problem. “The conjecture,” he writes, “that there are greater values than we can currently fathom does not imply that values are not defined in terms of our current dispositions.” And so, armed with a mystically irrefutable blanket assertion, he goes on to characterize value itself as a commodity to be amassed: “Transhumanism,” he writes, “promotes the quest to develop further so that we can explore hitherto inaccessible realms of value.”

Now I’ve deliberatively refrained from sarcasm up to this point, even though I think it is entirely deserved, given transhumanism’s troubling ideological tropes and explicit use of commercial advertising practices. You only need watch the OWN channel for five minutes to realize that hope sells. Heaven forbid I inject any anxiety into what is, on any account, an unavoidable, existential impasse. I mean, only the very fate of humanity lies in the balance. It’s not like your netflix is going to be cancelled or anything.

For those unfortunates who’ve read my novel Neuropath, you know that I am nowhere near as sunny about the future as I sound. I think the future, to borrow an acronym from the Second World War, has to be–has to be–FUBAR. Totally and utterly, Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition. Now you could argue that transhumanism is at least aware of this possibility. You could even argue, as some Critical Posthumanists (as David Roden classifies them) do, that FUBAR is exactly what we need, given that the present is so incredibly FU. But I think none of these theorists really has a clear grasp of the stakes. (And how could they, when I so clearly do?)

Transhumanism may not, as Nick Bostrom says, entail ‘technological optimism,’ but as I hope to show you, it most definitely entails scientific optimism. Because you see, this is precisely what falls between the cracks in debates on the posthuman: everyone is so interested in what Techno-Santa has in his big fat bag of More-better, that they forget to take a hard look at Techno-Santa, himself, the science that makes all the goodies, from the cosmetic to the apocalyptic, possible. Santa decides what to put in the bag, and as I hope to show you, we have no reason whatsoever to trust the fat bastard. In fact, I think we have good reason to think he’s going to screw us but good.

As you might expect, the word ‘human’ gets bandied about quite a bit in these debates–we are, after all, our own favourite topic of conversation, and who doesn’t adore daydreaming about winning the lottery? And by and large, the term is presented as a kind of given: after all, we are human, and as such, obviously know pretty much all we need to know about what it means to be human–don’t we?

Don’t we?

Maybe.

This is essentially Andy Clark’s take in Natural-born Cyborgs: Given what we now know about human nature, he argues, we should see that our nascent or impending union with our technology is as natural as can be, simply because, in an important sense, we have always been cyborgs, which is to say, at one with our technologies. Clark is a famous proponent of something called the Extended Mind Thesis, and for more than a decade he has argued forcefully that human consciousness is not something confined to our skull, but rather spills out and inheres in the environmental systems that embed the neural. He thinks consciousness is an interactionist phenomena, something that can only be understood in terms of neuro-environmental loops. Since he genuinely believes this, he takes it as a given in his consideration of our cyborg future.

But of course, it is nowhere near a ‘given.’ It isn’t even a scientific controversy: it’s a speculative philosophical opinion. Fascinating, certainly. But worth gambling the future of humanity?

My opinion is equally speculative, equally philosophical–but unlike Clark, I don’t need to assume that it’s true to make my case, only that it’s a viable scientific possibility. Nick Bostrom, of all people, actually explains it best, even though he’s arrogant enough to think he’s arguing for his own emancipatory thesis!

“Further, our human brains may cap our ability to discover philosophical and scientific truths. It is possible that the failure of philosophical research to arrive at solid, generally accepted answers to many of the traditional big philosophical questions could be due to the fact that we are not smart enough to be successful in this kind of enquiry. Our cognitive limitations may be confining us in a Platonic cave, where the best we can do is theorize about “shadows”, that is, representations that are sufficiently oversimplified and dumbed-down to fit inside a human brain.” (“Transhumanist Values”)

Now this is precisely what I think, that our ‘cognitive limitations’ have forced us to make do with ‘shadows,’ ‘oversimplified and dumbed-down’ information, particularly regarding ourselves–which is to say, the human. Since I’ve already quoted the opening passage from Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” it perhaps serves, at this point, to quote the closing passage. Speaking of the importance of civil freedom, Kant concludes: “Eventually it even influences the principles of governments, which find that they can themselves profit by treating man, who is more than a machine, in a manner appropriate to his dignity” (60). Kant, given the science of his day, could still assert a profound distinction between man, the possessor of values, and machine, the possessor of none. Nowadays, however, the black box of the human brain has been cracked open, and the secrets that have come tumbling out would have made Kant shake for terror or fury. Man, we now know, is a machine–that much is simple. The question, and I assure you it is very real, is one of how things like moral dignity–which is to say, things like value–arise from this machine, if at all.

It literally could be the case that value is another one of these ‘shadows,’ an ‘oversimplified’ and ‘dumbed-down’ way to make the complexities of evolutionary effectiveness ‘fit inside a human brain.’ It now seems pretty clear, for instance, that the ‘feeling of willing’ is a biological subreption, a cognitive illusion that turns on our utter blindness to the neural antecedents to our decisions and thoughts. The same seems to be the case with our feeling of certainty. It’s also becoming clear that we only think we have direct access to things like our beliefs and motivations, that, in point of fact, we use the same ‘best guess’ machinery that we use to interpret the behaviour of others to interpret ourselves as well.

The list goes on. But the only thing that’s clear at this point is that we humans are not what we thought we were. We’re something else. Perhaps something else entirely. The great irony of posthuman studies is that you find so many people puzzling and pondering the what, when, and how of our ceasing to be human in the future, when essentially that process is happening now, as we speak. Put in philosophical terms, the ‘posthuman’ could be an epistemological achievement rather than an ontological one. It could be that our descendants will look back and laugh their gearboxes off, the notion of a bunch of soulless robots worrying about the consequences of becoming a bunch of soulless robots.

So here’s the question I would ask Mr. Bostrom: Which human are you talking about? The one you hope that we are, or the one that science will show us to be?

Either way, transhumanism as praxis–as a social movement requiring real-world action like membership drives and market branding, is well and truly ‘forked,’ to use a chess analogy: ‘Better living through science’ cannot be your foundational assumption unless you are willing to seriously consider what science has to say. You don’t get to pick and choose which traditional illusion you get to cling to.

Transhumanism, if you think about it, should be renamed transconfusionism, and rebranded as X+.

In a sense what I’m saying is pretty straightforward: no posthumanism that fails to consider the problem of the human (which is just to say, the problem of meaning and value) is worthy of the name. Such posthumanisms, I think anyway, are little more than wishful thinking, fantasies that pretend otherwise. Why? Because at no time in human history has the nature of the human been more in doubt.

But there has to be more to the picture, doesn’t there? This argument is just too obvious, too straightforward, to have been ‘overlooked’ these past couple decades. Or maybe not.

The fact is, no matter how eloquently I argue, no matter how compelling the evidence I adduce, how striking or disturbing the examples, next to no one in this room is capable of slipping the intuitive noose of who and what they think they are. The seminal American philosopher Wilfred Sellars calls this the Manifest Image, the sticky sense of subjectivity provided by our immediate intuitions–and here’s the thing, no matter what science has to say (let alone a fantasy geek with a morbid fascination with consciousness and cognition). To genuinely think the posthuman requires us to see past our apparent, or manifest, humanity–and this, it turns out, is difficult in the extreme. So, to make my argument stick, I want to leave you with a way of understanding both why my argument is so destructive of transhumanism, and why that destructiveness is nevertheless so difficult to conceive, let alone to believe.

Look at it this way. The explanatory paradigm of the life sciences is mechanistic. Either we humans are machines, or everything from Kreb’s cycle to cell mitosis is magical. This puts the question of human morality and meaning in an explanatory pickle, because, for whatever reason, the concepts belonging to morality and meaning just don’t make sense in mechanistic terms. So either we need to understand how machines like us generate meaning and morality, or we need to understand how machines like us hallucinate meaning and morality.

The former is, without any doubt, the majority position. But the latter, the position that occupies my time, is slowly growing, as is the mountain of counterintuitive findings in the sciences of the mind and brain. I have, quite against my inclination, prepared a handful of images to help you visualize this latter possibility, what I call the Blind Brain Theory.

Imagine we had perfect introspective access, so that each time we reflected on ourselves we were confronted with something like this:

We would see it all, all the wheels and gears behind what William James famously called the “blooming, buzzing confusion” of conscious life. Would their be any ‘choice’ in this system? Obviously not, just neural mechanisms picking up where environmental mechanisms have left off. How about ‘desire’? Again, nothing we really could identify as such, given that we would know, in intimate detail, the particulars of the circuits that keep our organism in homeostatic equilibrium with our environments. Well, how about morals, the values that guide us this way and that? Once again, it’s hard to understand what these might be, given that we could, at any moment, inspect the mechanistic regularities that in fact govern our behaviour. So no right or wrong? Well, what would these be? Of course, given the unpredictability of events, the mechanism would malfunction periodically, throw its wife’s work slacks into the dryer, maybe have a tooth or two knocked out of its gears. But this would only provide information regarding the reliability of its systems, not its ‘moral character.’

Now imagine dialling back the information available for introspective access, so that your ability to perfectly discriminate the workings of your brain becomes foggy:

Now imagine a cost-effectiveness expert (named ‘Evolution’) comes in, and tells you that even your foggy but complete access is far, far too expensive: computation costs calories, you know! So he goes through and begins blacking out whole regions of access according to arcane requirements only he is aware of. What’s worse, he’s drunk and stoned, and so there’s a whole haphazard, slap-dash element to the whole procedure, leaving you with something like this:

But of course, this foggy and fractional picture actually presumes that you have direct introspective access to information regarding the absence of information, when this is plainly not the case, and not required, given the rigours of your paleolithic existence. This means, you can no longer intuit the fractional nature of your introspection intuitions, that the far-flung fragments of access you possess actually seem like unified and sufficient wholes, leaving you with:

This impressionistic mess is your baseline. Your mind. But of course, it doesn’t intuitively seem like an impressionistic mess–quite the opposite, in fact. But this is simply because it is your baseline, your only yardstick. I know it seems impossible, but consider, if dreams lacked the contrast of waking life, they would be the baseline for lucidity, coherence, and truth. Likewise, there are degrees of introspective access–degrees of consciousness–that would make what you are experiencing this very moment seem like little more than a pageant of phantasmagorical absurdities.

The more the sciences of the brain discover, the more they are revealing that consciousness and its supposed verities–like value–are confused and fractional. This is the trend. If it persists, then meaning and morality could very well turn out to be artifacts of blindness and neglect–illusions the degree to which they seem whole and sufficient. If meaning and morality are best thought of as hallucinations, then the human, as it has been understood down through the ages, from the construction of Khufu to the first performance of Hamlet to the launch of Sputnik, never existed, and, in a crazy sense, we have been posthuman all along. And the transhuman program as envisioned by the likes of Nick Bostrom becomes little more than a hope founded on a pipedream.

And our future becomes more radically alien than any of us could possibly conceive, let alone imagine.

April 10, 2013

Technocracy, Buddhism, and Technoscientific Enlightenment (by Benjamin Cain)

In “Homelessness and the Transhuman” I used some analogies to imagine what life without the naive and illusory self-image would be like. The problem of imagining that enlightenment should be divided into two parts. One is the relatively uninteresting issue of which labels we want to use to describe something. Would an impersonal, amoral, meaningless, and purposeless posthuman, with no consciousness or values as we usually conceive of them “think” at all? Would she be “alive”? Would she have a “mind”? Even if there are objective answers to such questions, the answers don’t really matter since however far our use of labels can be stretched, we can always create a new label. So if the posthuman doesn’t think, maybe she “shminks,” where shminking is only in some ways similar to thinking. This gets at the second, conceptual issue here, though. The interesting question is whether we can conceive of the contents of posthuman life. For example, just what would be the similarities and differences between thinking and shminking? What could we mean by “thought” if we put aside the na ve, folk psychological notions of intentionality, truth, and value? We can use ideas of information and function to start to answer that sort of question, but the problem is that this taxes our imagination because we’re typically committed to the naive, exoteric way of understanding ourselves, as R. Scott Bakker explains.

One way to get clearer about what the transformation from confused human to enlightened posthuman would entail is to consider an example that’s relatively easy to understand. So take the Netflix practice described by Andrew Leonard in “How Netflix is Turning Viewers into Puppets.” Apparently, more Americans now watch movies legally streamed over the internet than they do on DVD or Blu-Ray, and this allows the stream providers to accumulate all sorts of data that indicate our movie preferences. When we pause, fast forward or stop watching streamed content, we supply companies like Netflix with enormous quantities of information which their number crunchers explain with a theory about our viewing choices. For example, according to Leonard, Netflix recently spent $100 million to remake the BBC series House of Cards, based on that detailed knowledge of viewers’ habits. Moreover, Netflix learned that the same subscribers who liked that earlier TV show also tend to like Kevin Spacey, and so the company hired Kevin Spacey to star in the remake.

So the point isn’t just that entertainment providers can now amass huge quantities of information about us, but that they can use that information to tailor their products to maximize their profits. In other words, companies can now come much closer to giving us exactly what we objectively want, as indicated by scientific explanations of our behaviour. As Leonard says, “The interesting and potentially troubling question is how a reliance on Big Data [all the data that’s now available about our viewing habits] might funnel craftsmanship in particular directions. What happens when directors approach the editing room armed with the knowledge that a certain subset of subscribers are opposed to jump cuts or get off on gruesome torture scenes or just want to see blow jobs. Is that all we’ll be offered? We’ve seen what happens when news publications specialize in just delivering online content that maximizes page views. It isn’t always the most edifying spectacle.”

So here we have an example not just of how technocrats depersonalize consumers, but of the emerging social effects of that technocratic perspective. There are numerous other fields in which the fig leaf of our crude self-conception is stripped away and people are regarded as machines. In the military, there are units, targets, assets, and so forth, not free, conscious, precious souls. Likewise, in politics and public relations, there are demographics, constituents, and special interests, and such categories are typically defined in highly cynical ways. Again, in business there are consumers and functionaries in bureaucracies, not to mention whatever exotic categories come to the fore in Wall Street’s mathematics of financing. Again, though, it’s one thing to depersonalize people in your thoughts, but it’s another to apply that sophisticated conception to some professional task of engineering. In other words, we need to distinguish between fantasy- and reality-driven depersonalization. Military, political, and business professionals, for example, may resort to fashionable vocabularies to flatter themselves as insiders or to rationalize the vices they must master to succeed in their jobs. Then again, perhaps those vocabularies aren’t entirely subjective; maybe soldiers can’t psych themselves up to kill their opponents unless they’re trained to depersonalize and even to demonize them. And perhaps public relations, marketing, and advertising are even now becoming more scientific.

.

The Double Standard of Technocracy

Be that as it may, I’d like to begin with just the one, pretty straightforward example of creating art to appeal to the consumer, based on inferences about patterns in mountains of data acquired from observations of the consumer’s behaviour. As Leonard says, we don’t have to merely speculate on what will likely happen to art once it’s left in the hands of bean counters. For decades, producers of content have researched what people want so that they could fulfill that demand. It turns out that the majority of people in most societies have bad taste owing to their pedestrian level of intelligence. Thus, when an artist is interested in selling to the largest possible audience to make a short-term profit, that is, when the artist thinks purely in such utilitarian terms, she must give those people what they want, which is drivel. And if all artists come to think that way, the standard of art (of movies, music, paintings, novels, sports, and so on) is lowered. Leonard points out that this happens in online news as well. The stories that make it to the front page are stories about sex or violence, because that’s what most people currently want to see.

So entertainment companies that will use this technoscience (the technology that accumulates data about viewing habits plus the scientific way of drawing inferences to explain patterns in those data) have some assumptions I’d like to highlight. First, these content producers are interested in short-term profits. If they were interested in long-term ones and were faced with depressing evidence of the majority’s infantile preferences, the producers could conceivably raise the bar by selling not to the current state of consumers but to what consumers could become if exposed to a more constructive, challenging environment. In other words, the producers could educate or otherwise improve the majority, suffering the consumers’ hostility in the short-term but helping to shape viewers’ preferences for the better and betting on that long-term approval. Presumably, this altruistic strategy would tend to fail because free-riders would come along and lower the bar again, tempting consumers with cheap thrills. In any case, this engineering of entertainment is capitalistic, meaning that the producers are motivated to earn short-term profit.

Second, the producers are interested in exploiting consumers’ weaknesses. That is, the producers themselves behave as parasites or predators. Again, we can conclude that this is so because of what the producers choose to observe. Granted, the technology offers only so many windows into the consumer’s preferences; at best, the data show only what consumers currently like to watch, not the potential of what they could learn to prefer if given the chance. Thus, these producers don’t think in a paternalistic way about their relationship with consumers. A good parent offers her child broccoli, pickles, and spinach rather than just cookies and macaroni and cheese, to introduce the child to a variety of foods. A good parent wants the child to grow into an adult with a mature taste. By contrast, an exploitative parent would feed her daughter, say, only what she prefers at the moment, in her current low point of development, ensuring that the youngster will suffer from obesity-related health problems when she grows up. Likewise, content producers are uninterested in polling to discern people’s potential for greatness, by asking about their wishes, dreams, or ideals. No, the technology in question scrutinizes what people do when they vegetate in front of the TV after a long, hard day on the job. The content producers thus learn what we like when we’re effectively infantilized by television, when the TV literally affects our brain waves, making us more relaxed and open to suggestion, and the producers mean to exploit that limited sample of information, as large as it may be. Thus, the producers mean to cash in by exploiting us when we’re at our weakest, to profit by creating an environment that tempts us to remain in a childlike state and that caters to our basest impulses, to our penchant for fallacies and biases, and so on. So not only are the content producers thinking as capitalists, they’re predators/parasites to boot.

Finally, this engineering of content depends on the technoscience in question. Acquiring huge stores of data is useless without a way of interpreting the data. The companies must look for patterns and then infer the consumer’s mindset in a way that’s testable. That is, the inferences must follow logically from a hypothesis that’s eventually explained by a scientific theory. That theory then supports technological applications. If the theory is wrong, the technology won’t work; for example, the streamed movies won’t sell.

The upshot is that this scientific engineering of entertainment is based on only a partial depersonalization: the producers depersonalize the consumers while leaving their own personal self-image intact. That is, the content producers ignore how the consumers naively think of themselves, reducing them to robots that can be configured or contained by technology, but the producers don’t similarly give up their image of themselves as people in the na ve sense. Implicitly, the consumers lose their moral, in not their legal, rights when they’re reduced to robots, to passive streamers of content that’s been carefully designed to appeal to the weakest part of them, whereas the producers will be the first to trumpet their moral and not just their legal right to private property. The consumers consent to purchase the entertainment, but the producers don’t respect them as dignified beings; otherwise, again, the producers would think more about lifting these consumers up instead of just exploiting their weaknesses for immediate returns. Still, the producers think of themselves, surely, as normatively superior. Even if the producers style themselves as Nietzschean insiders who reject altruistic morality and prefer a supposedly more naturalistic, Ayn Randian value system, they still likely glorify themselves at the expense of their victims. And even if some of those who profit from the technocracy are literally sociopathic, that means only that they don’t feel the value of those they exploit; nevertheless, a sociopath acts as an egotist, which means she presupposes a double standard, one for herself and one for everyone else.

.

From Capitalistic Predator to Buddhist Monk

What interests me about this inchoate technocracy, this business of using technoscience to design and manage society, is that it functions as a bridge to imagining a possible posthuman state. To cross over in our minds to the truly alien, we need stepping stones. Netflix is analogous to enlightened posthumanity in that Netflix is part of the way toward that destination. So when we consider Netflix we stand closer to the precipice and we can ask ourselves what giving up the rest of the personal self-image would be like. So suppose a content provider depersonalizes everyone, viewing herself as well as just a manipulable robot. On this supposition, the provider becomes something like a Buddhist who can observe her impulses and preferences without being attached to them. She can see the old self-image still operating in her mind, sustained as it is by certain neural circuits, but she’s trained not to be mesmerized by that image. She’s learned to see the reality behind the illusion, the code that renders the matrix. So she may still be inclined in certain directions, but she won’t reflexively go anywhere. She has the capacity to exploit the weak and to enrich herself, and she may even be inclined to do so, but because she doesn’t identify with the crudely-depicted self, she may not actually proceed down that expected path. In fact, the mystery remains as to why any enlightened person does whatever she does.

This calls for a comparison between the posthuman’s science-centered enlightenment and the Buddhist kind. The sort of posthuman self I’m trying to imagine transcends the traditional categories of the self, on the assumption that these categories rest on ignorance owing to the brain’s native limitations in learning about itself. The folk categories are replaced with scientific ones and we’re left wondering what we’d become were we to see ourselves strictly in those scientific terms. What would we do with ourselves and with each other? The emerging technocratic entertainment industry gives us some indication, but I’ve tried to show that that example provides us with only one stepping stone. We need another, so let’s try that of the Buddhist.

Now, Buddhist enlightenment is supposed to consist of a peaceful state of mind that doesn’t turn into any sort of suffering, because the Buddhist has learned to stop desiring any outcome. You only suffer when you don’t get what you want, and if you stop wanting anything, or more precisely if you stop identifying with your desires, you can’t be made to suffer. The lack of any craving for an outcome entails a discarding of the egoistic pretense of your personal independence, since it’s only when you identify narrowly with some set of goals that you create an illusion that’s bound to make you suffer, because the illusion is out of alignment with reality. In reality, everything is interconnected and so you’re not merely your body or your mind. When you assume you are, the world punishes you in a thousand degrees and dimensions, and so you suffer because your deluded expectations are dashed.

Here are a couple of analogies to clarify how this Buddhist frame of mind works, according to my understanding of it. Once you’ve learned to drive a car, driving becomes second nature to you, meaning that you come to identify with the car as your extended body. Prior to that identification, when you’re just starting to drive, the car feels awkward and new because you experience it as a foreign body. When you’ve familiarized yourself with the car’s functions, with the rules of the road, and with the experience of driving, sitting in the driver’s seat feels like slipping on an old pair of shoes. Every once in a while, though, you may snap out of that familiarity. When you’re in the middle of an intersection, in a left turn lane, you may find yourself looking at cars anew and being amazed and even a little scared about your current situation on the road: you’re in a powerful vehicle, surrounded by many more such vehicles, following all of these signs to avoid being slammed by those tons of steel. In a similar way, a native speaker of a language becomes very familiar with the shapes of the symbols in that language, but every now and again, when you’re distracted perhaps, you can slip out of that familiarity and stare in wonder at a word you’ve used a thousand times, like a child who’s never seen it before.

What I’m trying to get at here is the difference between having a mental state and identifying with it, which difference I take to be central to Buddhism. Being in a car is one thing, identifying with it is literally something else, meaning that there’s a real change that happens when driving becomes second nature to you. Likewise, having the desire for fame or fortune is one thing, identifying with either desire is something else. A Buddhist watches her thoughts come and go in her mind, detaching from them so that the world can’t upset her. But this raises a puzzle for me. Once enlightened, why should a Buddhist prefer a peaceful state of mind to one of suffering? The Buddhist may still have the desire to avoid pain and to seek peace, but she’ll no longer identify with either of those or with any other desire. So assuming she acts to lessen suffering in the world, how are those actions caused? If an enlightened Buddhist is just a passive observer, how can she be made to do anything at all? How can she lean in one direction or another, or favour one course of action rather than another? Why peace rather than suffering?

Now, there’s a difference between a bodhisattva and a Buddha: the former harbours a selfless preference to help others achieve enlightenment, whereas the latter gives up on the rest of the world and lives in a state of nirvana, which is passive, metaphysical selflessness. So a bodhisattva still has an interest in social engagement and merely learns not to identify so strongly with that interest, to avoid suffering if the interest doesn’t work out and the world slams the door in her face, whereas a Buddha may extinguish all of her mental states, effectively lobotomizing herself. Either way, though, it’s hard to see how the Buddhist could act intelligently, which is to say exhibit some pattern in her activities that reflects a pattern in her mind and acts at least as the last step in the chain of interconnected causes of her actions. A bodhisattva has desires but doesn’t identify with them and so can’t favor any of them. How, then, could this Buddhist put any morality into practice? Indeed, how could she prefer Buddhism to some other religion or worldview? And a Buddha may no longer have any distinguishable mental states in the first place, so she would have no interests to tempt her with the potential for mental attachments. Thus, we might expect full enlightenment in the Buddhist sense to be a form of suicide, in which the Buddhist neglects all aspects of her body because she’s literally lost her mind and thus her ability to care or to choose to control herself or even to manage her vital functions. (In Hinduism, an elderly Brahmin may choose this form of suicide for the sake of moksha, which is supposed to be liberation from nature, and Buddhism may explain how this suicide becomes possible for the enlightened person.)

The best explanation I have of how a Buddhist could act at all is the Taoist one that the world acts through her. The paradox of how the Buddhist’s mind could control her body even when the Buddhist dispenses with that mind is resolved if we accept the monist ontology in which everything is interconnected and so unified. Even if an enlightened Buddha loses personal self-control, this doesn’t mean that nothing happens to her, since the Buddhist’s body is part of the cosmic whole, and so the world flows in through her senses and out through her actions. The Buddhist doesn’t egoistically decide what to do with herself, but the world causes her to act in one way or another. Her behaviour, then, shouldn’t reflect any private mental pattern, such as a personal character or ego, since she’s learned to see through that illusion, but her actions will reflect the whole world’s character, as it were.

.

From Buddhist Monk to Avatar of Nature

Returning to the posthuman, the question raised by the Buddhist stepping stone is whether we can learn what it would be like to experience the death of the manifest image, the absence of the na ve, dualistic and otherwise self-glorifying conception of the self, by imagining what it would be like to be the sun, the moon, the ocean, or just a robot. That’s how a scientifically enlightened posthuman would conceive of “herself”: she’d understand that she has no independent self but is part of some natural process, and if she’d identify with anything it would be with that larger process. Which process? Any selection would betray a preference and thus at least a partial resurrection of the ghostly, illusory self. The Buddhist gets around this with metaphysical monism: if everything is interconnected, the universe is one and there’s no need to choose what you are, since you’re metaphysically everything at once. So if all natural processes feed into each other, nature is a cosmic whole, and the posthuman sees very far and wide, sampling enough of nature to understand the universe’s character so that she’d presumably understand her actions to flow from that broader character.

And just here we reach a difference between Eastern (if not specifically Buddhist) and technoscientific enlightenment. Strictly speaking, Buddhism is atheistic, I think, but some forms of Buddhism are pantheistic, meaning that some Buddhists personify the interconnected whole. If we suppose that technoscience will remain staunchly atheistic, we must assume only that there are patterns in nature and not any character or ghostly Force or anything like that. Thus, if a posthuman can’t identify with the traditional myth of the self, with the conscious, rational, self-controlling soul, and yet the posthuman is to remain some distinct entity, I’m led to imagine this posthuman entity as an avatar of lifeless nature. What does nature do with its forces? It evolves molecules, galaxies, solar systems, and living species. The posthuman would be a new force of nature that would serve those processes of complexification and evolution, creating new orders of being. The posthuman would have no illusion of personal identity, because she’d understand too well the natural forces at work in her body to identify so narrowly and desperately with any mere subset of their handiwork. Certainly, the posthuman wouldn’t cling to any byproduct of the brain, but would more likely identify with the underlying, microphysical patterns and processes.

So would this kind of posthumanity be a force for good or evil? Surely, the posthuman would be beyond good or evil, like any natural force. Moral rules are conventions to manage deluded robots like us who are hypnotized by our brain’s daydream of our identity. Values derive from preferences of some things as better than others, which in turn depend on some understanding of The Good. In the technoscientific picture of nature, though, goodness and badness are illusions, but this doesn’t imply anything like the Satanist’s exhortation to do whatever you want. The posthuman would have as many wants as the rain when the rain falls from the sky. She’d have no ego to flatter, no will to express. Nevertheless, the posthuman would be caused to act, to further what the universe has already been doing for billions of years. I have only a worm’s understanding of that cosmic pattern. I speak of evolution and complexification, but those are just placeholders, like an empty five-line staff in modern musical notation. If we’re imagining a super-intelligent species that succeeds us, I take it we’re thinking of a species that can read the music of the spheres and that’s compelled to sing along.

April 4, 2013

A Material Churl in A Material World

Aphorism of the Day: The cup of ego always but always leaks on the doily of theory. Thus the philosophical tendency to embroider in black.

.

I’d like to thank Roger for introducing a little high-altitude class into TPB while I was undergoing intense tequila retoxification treatment in Mexico. I’ll be providing my own naturalistic gloss on his metaphilosophical observations at some point over the ensuing weeks. In the meantime, however, I need to do a little spring cleaning…

Since I plan on shortly rowing back into more Analytic waters I thought I would fire a couple of more broadsides across the Continental fleet as I bring my leaky rowboat about. The (at times heated) debate we had following “The Ptolemaic Restoration,” has left me more rather than less puzzled by the ongoing ‘materialistic turn’ in Continental circles. Object Oriented Ontology has left me particularly mystified, especially in the wake of Levi Bryant’s claim that ‘object orientation’ need not concern itself with the question of meaning, even though, historically speaking, this question has always posed the greatest challenge to materialist accounts. As Ray Brassier acknowledges in his 2012 After Nature interview:

[Nihil Unbound] contends that nature is not the repository or purpose and that consciousness is not the fulcrum of thought. The cogency of these claims presupposes an account of thought and meaning that is neither Aristotelian–everything has meaning because everything exists for a reason–nor phenomenological–conscious is the basis of thought and the ultimate source of meaning. The absence of any such account is the book’s principal weakness…

What is truth? What is meaning? What is subjectivity? In short, What is intentionality? These are absolutely pivotal philosophical questions for any philosophy that purports to be ‘materialist.’ Why? Because if we actually had some way of naturalizing these perplexities, then we could plausibly claim that everything is material. And yet Bryant, when pressed on this selfsame issue, responds:

I’m not working on issues of intentionality. Asking me to have a detailed picture of intentionality is a bit like asking a neurologist to have a detailed picture of quantum mechanics or black holes. It’s just not what neurologists are doing. I’ll leave it to the neurologists to give that account of intentionality” (Comments to “The Ptolemaic Restoration,” March 14, 2013 6:45pm)