Daniel H. Pink's Blog, page 10

February 7, 2012

Help Kathryn come up with a job title

Kathryn, a reader in Canada, wrote to me last week asking for some advice. Since history has shown that your advice is always way better than mine, I'm posing her challenge to you, Dear Readers.

Kathryn, a reader in Canada, wrote to me last week asking for some advice. Since history has shown that your advice is always way better than mine, I'm posing her challenge to you, Dear Readers.

She writes:

"I'd just finished your book, Drive, when I was approached out of the blue about taking on a new and exciting job working with a cutting edge athletic performance and rehabilitation centre.

"The role entails strategic thinking, visioning, marketing, promoting, branding, building a sense of community within the training facility and 'managing' a team of health care providers and trainers.

"They have in the past had two horrible managers and the team is really quite demoralized. . . . But I am looking forward to taking on this role and helping the team develop their sense of autonomy, mastery and purpose.

"The owner is calling the position the Clinic and Gym Manager. Blah!!! I'm not certain that term will endear me too much to my new team.

"Any suggestions around alternative titles?"

So, folks, what do you recommend for Kathryn's job title?

Put your suggestions in the Comments section. Then — seriously — Kathryn will choose the one she likes best.

February 6, 2012

Free management consulting — only on today's Office Hours!

If you have any interest in picking the brain of one of the top management thinkers of our times — and thereby cadge thousands of bucks in free consulting — tune in to Office Hours today at 2pm, EST.

If you have any interest in picking the brain of one of the top management thinkers of our times — and thereby cadge thousands of bucks in free consulting — tune in to Office Hours today at 2pm, EST.

Our guest will be Gary Hamel. He's the originator (with CK Prahalad) of the idea of core competencies, a visiting professor at the London Business School, the most reprinted writer in the history of the Harvard Business Review, founder of the Management Innovation eXchange, and pioneer in the quest for "moonshots for management." He's also the author of What Matters Now, a terrific book that came out last week. (Buy it on IndieBound, BN.com, or Amazon.)

To listen in and ask Gary a question, just call (703) 344-2171 at the appointed hour and used this passcode: 203373.

The program is free of charge and free of advertising. For more information — including previous guests, audio downloads, and listening to it on iTunes — just visit the Office Hours page.

January 30, 2012

Emotionally intelligent signage and Louis C.K.

Comedian Louis C.K. garnered a lot of press — and made a ton of money — last month when he disintermediated the major television networks and released his latest special as a $5 download on his web site.

Less well known is that the funny man (if you haven't seen this bit, you need to) used emotionally intelligent signage to discourage fans from ripping off his intellectual property and distributing it for free.

It seems to have worked.

(HT: The great Kevin Kelly, who pointed this out to me.)

January 25, 2012

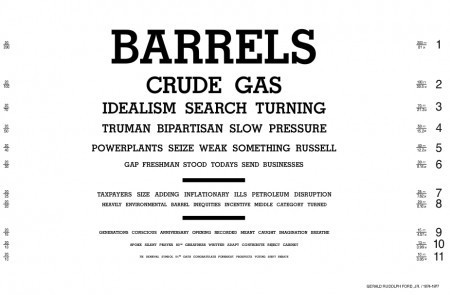

State of the Union address as an eye exam chart

Can a Presidential speech ever be a work of art?

Not usually. But R. Luke Dubois is doing his best. As part of the "Mulitplicity" exhibit now showing at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which I had a chance to see last weekend, Dubois reconfigured all the State of the Union addresses in an interesting way.

In a series of prints called "Hindsight is always 20/20," he's taken the words of each speech, noted their frequency, and rendered them as a Snellen eye exam chart – with a President's most-used words in large type near the top and his less-used words in progressively smaller type toward the bottom.

It's a mashup – one part word cloud, another part optometry. And it works. You get a good sense of how much the times dictate the words. It also offers a sly commentary on each President's – wait for it – vision.

Check out two samples (Theodore Roosevelt and Gerald Ford) below and more pieces here.

January 24, 2012

5 great guests on our new season of Office Hours

Good news, folks. Office Hours is back for a new season!

Good news, folks. Office Hours is back for a new season!

The madness begins this Friday, January 27, at 11am, EST, when our guest will be Susan Cain, author of the hot new book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. (That's her on the right.)

For those of you who've missed the biggest cultural phenomenon since Cop Rock, Office Hours is our radio-ish program, now available around the world on iTunes, in which I and a special guest open up the phone lines for an hour to take your questions about work, life, business, education, and anything that's on your mind. Think of it like this: It's Car Talk . . . for the human engine.

You can listen in live, and ask a question, by calling (703) 344-2171 at the appointed day and time — and entering this passcode: 203373.

Don't forget: Sign up on the Office Hours web page to be reminded of this and future episodes. We've got some amazing guests over the next few months:

February

Gary Hamel, one of the world most influential management thinkers and author of What Matters Now. (Feb 6 at 2pm, EST)

March

Harvey Mackay, the sales and networking legend and author of The Mackay MBA of Selling in the Real World. (March 8 at 1pm, EST)

April

Jonah Lehrer, the prolific Wired and New Yorker contributor and author of Imagine, a cool new book about the science of creativity. (April 6 at 1pm, EDT)

May

Tom Peters, the man the LA Times called "the father of the post-modern corporation" and the recent purveyor of the mother of all presentations. (May 18 at 2pm, EDT)

Remember:

Join us on January 27 to talk introversion with Susan Cain.

Sign up here to be notified of future episodes.

Listen to previous shows on iTunes.

January 19, 2012

Does being reminded of money make you an uncooperative jerk or an independent thinker?

Dedicated readers know that I've written a fair bit on how contingent rewards, including money, can go awry in all sorts of ways — resulting in poorer performance, diminished creativity, reduced interest in tasks that were once intrinsically interesting, and so on.

Dedicated readers know that I've written a fair bit on how contingent rewards, including money, can go awry in all sorts of ways — resulting in poorer performance, diminished creativity, reduced interest in tasks that were once intrinsically interesting, and so on.

But can the very idea of money also affect our behavior?

In an interesting new paper, Jia Liu, Dirk Smeesters, and Kathleen D. Vohs say "You betcha."

The researchers carried out a sneaky experiment that had two components. First, they asked their participants to fill out a questionnaire on a computer. The questionnaire itself wasn't important. What was important was the desktop wallpaper. For half the participants, the wallpaper showed a pattern of shells; for the other half, it showed a pattern of Euro notes and coins. (In the parlance of social psychology, that second group was "primed" with money.)

Next, they took the participants and another person of the same gender into a room and gave them a beverage to taste. This is a new sports drink called Vigor, they told their subjects, and we want your opinion of it for a marketing study.

A minute later, the other person — who was actually the experimenters' confederate — got up to leave the room, mentioning that he or she had already tasted the drink. Some of the confederates added, "This drink tastes really good. I just love it." Some said, "This drink tastes really bad. I just hate it." Some said nothing.

Then came the test: Did the money prime make any difference in the participants' opinions about the beverage?

Ample research, especially the extraordinary work of Robert Cialdini, has shown we're quite susceptible to social influence. When we hear that other folks like something, we tend to like it, too. And that pattern held — at least for the people who saw shells in their computer background. These folks liked the beverage more when the confederate said he or she liked it and less when the confederate said he or she didn't like it.

But for the subjects primed with money — again, just some background images of Euros — the response was the exact opposite. As the researchers write:

The confederate's passing comments exerted a backfiring effect on evaluations of the drink among participants for whom the idea of money had been activated. They liked it more when the confederate said that the drink was bad and less when the confederate said the drink was good. (Emphasis added.)

What's going on?

Liu, Smeesters, and Vohs say that money cues can operate as threats and "produce contrarian reactions that are the opposite of the source's intent." Other research has shown that being reminded of money can make people more single-minded and more apt to work harder — but also less social, less cooperative, and less likely to help others.

It's a bit odd, they explain. "Money has bigger effects on people's thoughts, feelings, and behavior than simply what it can do as an exchange medium or store of value . . . Mere reminders of it are enough to drastically change people's preferences for work, play, and interpersonal relationships."

So the next time you try to raise the issue of moolah in an effort to persuade a prospect or an employee, think twice. Making it all about the coin can sometimes get you the opposite of what you want.

January 18, 2012

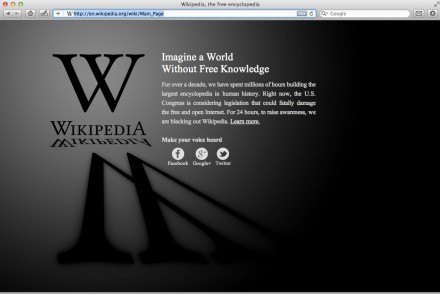

Tomorrow's classroom excuse: SOPA ate my homework

In case you haven't heard, several large websites have blacked themselves out today to protest two pieces of anti-piracy legislation now before the U.S. Congress.

Leaving aside the merits of their arguments, which I think outweigh the merits of the legislation's advocates' arguments, I've got two questions.

1. Will Wikipedia's 24-hour disappearance have a material effect on anyone's life? (I'm talking about you, students and journalists.) If so, that's pretty amazing — given how preposterous the very concept of Wikipedia seemed not too long ago.

2. Will the web blackout become a prominent new form of social protest? As a long-time resident of America's capital city, I'm convinced that the "March on Washington" technique passed its sell-by date last century. If this is the replacement, or even a quasi-replacement, then we're watching history in action.

Maybe we'll know the answers tomorrow. At the very least, we'll be able to finally find out the capital of Slovakia.

January 10, 2012

3 equations that can change your life

Chip Conley is a rare bird. He's a successful entrepreneur, a provocative thinker, and — get this — a nice guy. Today, he's out with his newest book, Emotional Equations: Simple Truths for Creating Happiness + Success, and it's a gem. (Buy it at Amazon

Chip Conley is a rare bird. He's a successful entrepreneur, a provocative thinker, and — get this — a nice guy. Today, he's out with his newest book, Emotional Equations: Simple Truths for Creating Happiness + Success, and it's a gem. (Buy it at Amazon BN.com, or IndieBound.)

BN.com, or IndieBound.)

In the book, Chip uses the grammar and lexicon of arithmetic to some deeper truths about life. (Ex: Joy = Love – Fear.) Much like math itself, the technique is simple and elegant — so much so that I wanted to introduce it to Pink Blog readers.

In the short interview below, I ask Chip to explain three particularly intriguing emotional equations:

You define despair as suffering minus meaning (Despair = Suffering – Meaning). What does that mean?

Viktor Frankl's landmark book "Man's Search for Meaning" was my salvation 3-4 years ago when I was going through a depressing time. I turned that profound book into this equation so that it could serve as a daily reminder or mantra on a bad day. Suffering is basically a constant in life. If you're a Buddhist, that's the first Noble Truth, but it's just as relevant in a punishing recession and in many relationships. Meaning is the variable – it's what you make of it. The way this equation works, if you increase the meaning of something and suffering stays constant, then despair declines. For me, it meant I was asking "What's the lesson or learning in this?" Often, I had to think of life as sort of an emotional boot camp and that the way I created meaning from a challenging situation was to imagine what emotional muscles I was training – whether it's resiliency, humility, compassion, or courage – that could serve me later in life.

For Anxiety, you turn to multiplication. You say it's the product of Uncertainty and Powerlessness (Anxiety = Uncertainty x Powerlessness). Explain.

Experts in Anxiety distill the ingredients down to two primary elements: what we don't know and what we can't control. I created an Anxiety Balance Sheet to assist with alleviating this debilitating emotion. Imagine something that's making you feel anxious. Then, pull out a piece of paper and create four columns with the first one being "what I do know" about this issue that's creating anxiety. The second column would be "what I don't know" (these first two columns cover the "Uncertainty" part of the equation). The third column is "what I can influence" and the fourth is "what I can't influence." Take ten minutes to list as many items under each column as possible. What I've found is that most people are surprised when they have more items under the "good" columns (1 and 3) than they have under the "bad" (2 and 4). Additionally, you can look at what's in column 2 (what you don't know) and ask how could I learn more. In fact, if you're worried you may lose your job, the answer may be to ask your boss if your job is in jeopardy. And, I've also seen people move items from column 4 to 3 by asking themselves, "How can I create some influence on this issue even though I'm not feeling it right now?" Just the act of getting logical and proactive about anxiety helps to loosen its grip on you.

Does that mean if we declare that we will never be powerless — that is, if we reduce the Powerlessness component to zero — we'll be anxiety-free?

Provocative question. You may have heard about a social science experiment in which research subjects were given the choice of either receiving a very painful electric shock now or receiving half as painful of a shock sometime in the next 24 hours but at a time when they weren't expecting it. The majority of people chose to experience the extra pain now since mental pain can be more threatening than physical pain (note to leaders: better to deliver bad news as early as possible). In an updated version of this study, they gave people the ability to have a little more power over when the shock could occur – I think it was within a one hour window – and this led people to being more inclined to choose the pain later rather than the excessive pain now. In a multiplicative equation, if one of the two variables edges toward zero, it takes away the combustibility. So, if you tell yourself that you have huge job insecurity which is leading to uncertainty, but you are doing all kinds of prep work (job interviews, making connections on LinkedIn, saving some money) that give you more of a sense of power, then it's likely to lessen the feeling of anxiety.

Surprisingly, your equation for Happiness — which we often think of in terms of more — uses division. (Wanting What You Have / Having What You Want). How does that work?

I learned this one studying the Gross National Happiness index in Bhutan for a week three years ago. An alternative way of looking at this equation is Happiness = Practicing Gratitude / Pursuing Gratification. When you appreciate or want what you have, that's a form of practicing gratitude, something that is foundational for many devotional practices – like Buddhism in Bhutan. In the U.S., we are proud of our "pursuit of happiness" and the fact that it's even in our Declaration of Independence, but if you read some dictionary definitions of pursuit ("to chase with hostility"), you understand the risks associated in the denominator. Many of us pursue our goals or gratifications so aggressively that we end up on the hedonic treadmill constantly chasing the next shiny object or opportunity. When we're bottom-heavy in this equation and too focused on pursuit, we lose track of our quickest means of creating happiness: the practice of wanting what we have or gratitude. So, yes Dan, in some ways, happiness does have an editing function.

January 6, 2012

Sign of the day: Should you take that elevator?

Alastair Dryburgh of London sends this glorious example of emotionally intelligent signage, which he spotted next to the elevators (aka, the lifts) at the Tate Modern.

It makes one think. And, I'm guessing, it makes more than one head for the stairwell.

January 2, 2012

How to make a New Year's non-resolution

Man, am I glad it's a new year. I need a re-boot. And as I contemplated my resolutions for 2012, I reached out to Kelly McGonigal for some guidance.

Man, am I glad it's a new year. I need a re-boot. And as I contemplated my resolutions for 2012, I reached out to Kelly McGonigal for some guidance.

Kelly is a Stanford lecturer and author of the terrific new book, The Willpower Instinct (Buy it at Amazon , BN.com, or IndieBound) that explores the psychology, economics, and neuroscience of self-control and that offers some compelling (and counter-intuitive) advice.

, BN.com, or IndieBound) that explores the psychology, economics, and neuroscience of self-control and that offers some compelling (and counter-intuitive) advice.

Here's our short interview:

You say that instead of making a New Year's resolution, we should instead pledge not to change something in our lives. Why?

Most people make a fundamental mistake when thinking about their future choices. We wrongly but persistently expect to make different decisions tomorrow than we do today.

I'll skip the gym today, but I'm sure I'll go tomorrow. I'll put this on my credit card today, but no more shopping for a month. I don't want to get started on the project now, but I'll tackle it first thing in the morning. The more people have faith in their futures selves, the more likely they are to indulge today. In fact, just knowing you'll have the chance to choose again tomorrow increases the chance you'll choose habit or vice today.

Behavioral economics provides an interesting solution. When you want to change a behavior, aim to reduce the variability in your behavior, not the behavior itself.

What do you mean by "variability?"

Take, for example, a smoker who wants to quit but can't. The typical approach is to set a goal to smoke fewer cigarettes – or even quite out right. But imagine instead that the smoker simply tries to smoke the same number of cigarettes every day. Research shows that they will gradually decrease their overall smoking– even when they are explicitly told not to try to smoke less.

Hmmm. How does that work?

They are deprived of the usual cognitive crutch of pretending that tomorrow will be different. Every cigarette becomes not just one more smoked today, but one more smoked tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that. For someone who really wants to quit, this is exactly the reality check that makes change possible.

So what do we say to ourselves in the moment of temptation to give ourselves that reality check?

Force yourself to view every individual choice as a commitment to all future choices. So instead of asking, "Do I want to eat this candy bar now?" (while lying to yourself that you won't eat another candy bar all week), ask yourself, "Do I want the consequences of eating a candy bar every afternoon for the next year?" When tempted to procrastinate, don't ask yourself "Would I rather do this today or tomorrow?" Instead, ask "Do I want the consequences of always putting this off until tomorrow?"

Okay. So what you are you resolving not to change this year?

Over the years, I've made a number of no-change resolutions that have stuck, including exercising every day (instead of taking the consequences of not exercising every day). So I know it works! This year I'm aiming to reduce variability in my sleep. I've been an inconsistent sleeper all my life with a lot of temptations to both stay up and sleep in. There's fascinating research coming out about the physical and mental health benefits of not just getting enough sleep, but keeping a predictable sleep schedule. People should feel free to email me at 2 AM or check my Twitter feed timestamp so to see I'm keeping my word.