Daniel H. Pink's Blog, page 9

March 12, 2012

Snuffing out smoking on a French train: Your solutions

One day last fall, Marie-Dominique Bonardi, a professor of public relations at Sorbonne University, posed a problem to PinkBlog readers: A group of smokers at a commuter train station in France takes over one car each day, "and spends the whole journey smoking and preventing other people from using the wagon." When other commuters do manage to board the car, their lungs pay the price.

One day last fall, Marie-Dominique Bonardi, a professor of public relations at Sorbonne University, posed a problem to PinkBlog readers: A group of smokers at a commuter train station in France takes over one car each day, "and spends the whole journey smoking and preventing other people from using the wagon." When other commuters do manage to board the car, their lungs pay the price.

Even though smoking on the trains is illegal, this behavior has been going on for 10 years and clearly isn't going to stop on its own. What to do?

You offered an array of terrific solutions, most of which fell into four categories:

Sticks: Punish the smokers, you said – turn the electricity off in the car, install smoke-activated sprinklers or brakes, squirt water in smokers' faces. Liz proposed playing annoying music in the smoking car (e.g., Barry Manilow). Ed Hitchcock suggested choosing a date on which the smoking ban will begin to be actively enforced, advertise the date in advance, and then – enforce it. "Give out fines, revoke their tickets, and all the other consequences you would expect."

Monetize it: How about putting a price tag on smoking? W. Corey Trench suggested, "If a smoker is willing to pay for his habit, and the added taxes to fund advertising and healthcare, then he will be willing to pay extra for the privilege of riding in a smoking car and all the attendant costs of its operations." John Strosnider added an interesting twist: "Allow people to 'adopt' a wagon. Have an auction each month….Whichever group wins gets to set the rules for their wagon for that month."

The social approach: Quite a few suggestions mined the power of peer pressure and social influence, with a little train theater thrown in. David Caswell suggested handing out cheap surgical masks: "Imagine how much of a dork you'd feel if you're sitting on the train with a lit cigarette while everyone else is wearing a face mask!" Ritch suggested seeding the smoking car with bean-fed commuters: "Schedule these 'walk-by tootings' each week…until the smokers relent. Let the metaphor speak." Several readers proposed emotionally intelligent signage that highlights the risks of smoking to self and others, along the lines of these Japanese signs (via Samuel Feldman). Perry unveiled the ultimate weapon: "I suggest a crowd of mimes rush onto the wagon and make coughing and choking gestures."

C'est la vie: A few readers claimed that this behavior – rule-breaking, smoking, train-hogging – is so typically French that it's best just to live with it. Zut alors! Jim Hayward counters, "I live in Ontario, Canada and over the last forty years there has been a definite shift to smoking not being acceptable in public places. This has been a concerted program of the government to reduce health care cost and has broad support."

A multi-faceted problem like the one Marie-Dominique brought to us requires a multi-faceted solution: some combination of emotionally intelligent persuasion, disruption, theater, social influence, and yes, maybe a few carrots and sticks. The entire comment thread is well worth reading, including Marie-Dominique's response.

P.S. Stay tuned. We're about to make this crowdsourced management consulting a regular feature!

March 6, 2012

The power of habits — and the power to change them

Human beings, we've been told, are creatures of habit. If we do something one way on Tuesday, odds are we'll do that same thing the same way on Wednesday.

Sometimes that helps us. Think about those who floss regularly and can't imagine otherwise. Other times, it can rot our brains and hollow our souls. Think about those who arrive home each night and unthinkingly switch on the TV.

So how do habits come to be? And how can we change them?

Charles Duhigg is a reporter for the New York Times who's written a new (and fascinating) book on the subject. It's called The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business — and it's already climbing the bestseller lists. (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound.)

One of my bad habits is interviewing authors about their books. Against his better judgment, Charles fed that habit and answered a few questions. Here's a piece of our conversation:

1. All of us have a sense from our day-to-day lives of what a habit is. But you've dissected habits into a three-part loop. Explain. And give an example.

In the last 15 years, as we've learned how habits work and how they can be changed, scientists have explained that every habit is made up of a cue, a routine and a reward. The cue is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine – the behavior itself – which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular habit is worth remembering for the future. Over time, this loop — cue, routine, reward; cue, routine, reward — becomes more automatic as the cue and reward become neurologically intertwined.

Take exercise. Studies have shown that people who identify simple cues and clear rewards are more likely to establish consistent exercise habits. If you want to start running in the morning, for instance, research indicates you're more likely to succeed if you choose an obvious cue (like always putting on your sneakers before breakfast or leaving your running clothes next to your bed) and a clear reward (like a treat afterwards or the sense of accomplishment that comes from recording your miles in a log book). After a while, your brain will start anticipating that reward — craving the treat or the feeling of accomplishment — and there will be a measurable neurological impulse to exercise each day.

2. You write that a rather astonishing amount of what we do each day is unconscious and habitual rather than conscious and volitional. Should that alarm us? Does it mean we have a lot less free will than we think?

One paper published by a Duke University researcher in 2006 found that more than 40 percent of the actions people performed each day weren't the due to decision making, but were habits. In a sense, that's alarming because when we're in the middle of a habit, we're thinking less. Our neurological activity literally decreases as the habit unfolds. That's why the behavior feels so automatic, almost unconscious.

But that doesn't mean that habits are destiny. Habits can be ignored, changed, or replaced. And studies show that simply understanding how habits work — learning the structure of the habit loop — makes them easier to control. Once you break a habit into its components, you can fiddle with the gears.

The secret, however, is to identify the cues and rewards driving particularly behaviors, and then adhere to what is known as the Golden Rule of Habit Change: only change one part of the loop at a time. To change a routine, for instance, keep the old cue and find a routine that delivers an old reward. Don't try to change everything at once.

3. Let's say that Pink Blog readers have a habit — eating junk food, frittering time away on email, procrastinating on big projects — that they'd like to eliminate. What's the most effective step they can take?

It's important to understand that you can't eliminate a habit – you can only change it for a better alternative. And the single most effective step is identifying the cue (what triggers the behavior) and the reward (what craving it satisfies.) For instance, I had a bad habit of eating a cookie every afternoon. To change it, I identified the cue by paying close attention to what preceded my cookie urge. Research indicates that most cues fit into one of five categories: location, time, emotional state, other people or the immediately preceding action. So whenever my cookie habit hit, I wrote down where I was, the time, how I felt, who else was around and what I had just done. Pretty soon, the cue was clear: I always felt an urge to snack around 3:30.

I also needed to figure out the reward. So, I conducted a few experiments. One day, when I felt a cookie impulse, I went for a walk instead. The next day, I bought a coffee. The next, an apple. I wanted to test different theories regarding what reward I was really craving. Was it hunger? Or the desire for a quick burst of energy? Or, as turned out to be the answer, was it that I wanted to socialize, and the cookie was just a convenient excuse?

Once I figured out the cue and reward, it was fairly simple to shift the routine. Now, every day around 3:30, I stand up, look around for someone to talk to, spend 10 minutes gossiping, then go back to my desk. The cue and reward have stayed the same. Only the routine has shifted, and I've lost 21 pounds since then.

March 2, 2012

Root canals, baptisms, and emotionally intelligent parking signs

As always, the Pink, Inc., mail bag is brimming with emotionally intelligent signs sent by readers around the world. Here are two that attempt to use signage and humor to enforce parking regulations.

John Huntoon snapped this photo when he went to visit his dentist in Cardiff by the Sea, California:

And several readers have sent versions of this sign, which apparently adorns more than a few church parking lots:

Odontophobics and atheists, be warned!

If you've seen a sign, emotionally intelligent or otherwise, that you want to share, just send us an email.

February 29, 2012

Can a tomato make you more productive?

My quest to get more and better work done is endless — but not nearly as endless as my willingness to blab about that quest with anyone who'll listen.

In the last few months, a few wise souls who've counseled me have leaned in, Mr. McGuire-like, and whispered in my ear a single word: Pomodoro.

What-the-heck-o?

Pomodoro. It's Italian for tomato, and it turns out to be a deceptively simple time management hack with a growing fan base. Some Pink Blog readers, no doubt, have heard of it. But to me, this tomato was super fresh.

All you need is a kitchen timer — in Italy, kitchen timers are traditionally tomato-shaped — pencil, paper, and task that needs to be done. The Pomodoro Technique website has more details, but basically you set a kitchen timer for 25 minutes, work until the bell rings, and then take a 5-minute break. After four of these "pomodoros," you've earned a 15-minute break (the pencil and paper are for keeping track).

You could stick with a kitchen timer or even your iPhone. But here are a few apps, gadgets, widgets, and websites that make pomodoro-ing even more fun:

25 Minutes

CherryTomato

Pomodoro for Mac

Pomodori (also for Mac)

Tomatoi.st

FocusBooster

Tomighty

(BTW, if you like this idea, you might also dig the post, The Power of an Hourly Beep, from back in October.)

February 28, 2012

Would getting rid of cash make our lives easier and better?

On Sunday night I did something that, when you stop and think about it for a moment, was weird.

Accompanied by SaulonSports, I drove to Ray's Hell Burger to pick up dinner for ourselves and our fellow Pinks. We asked for five burgers. And the folks behind the counter gave them to us in exchange for — get this — three pieces of paper.

Three pieces of paper!

Yes, they were two 20-dollar bills and one Hamilton. But still, we obtained something of value (including a B.I.G. Poppa!) by handing over a few strips of fiber that have no inherent worth.

In his new book, The End of Money: Counterfeiters, Preachers, Techies, Dreamers — and the Coming Cashless Society, David Wolman explores the conundrums and complexities of cash. (Buy the book at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound.)

He argues that bills and coins are inefficient and expensive — for example, a U.S. nickel costs 11.2 cents to make – and that we'd be better off without it. In fact, he tried to go a year without using any cash at all.

The book is fascinating — so much so that I asked David to answer some questions for Pink Blog readers.

You tried to avoid using physical money for an entire year. What changes in your daily habits or ways of thinking were you forced to make? And have you gone back to using coins and bills?

The biggest hangup for me–both during the cashless year and now–is tipping. While foregoing cash, I made sure, for example, never to get help from a curbside porter at an airport or bellhop at a hotels, no matter how heavy my suitcases. Now I've loosened up on that, especially during a recent family vacation, which included a duffle bag that I would swear was packed with silver bullion. I also steered clear of farmers markets; many of those vendors still only accept cash, although I think that's changing. I tell ya, I can't wait for the day when I can tip or buy some strawberries with an exchange as simple as a text message.

As some people know, I harbor a long-standing animus against pennies. You talk about this issue in your book – pennies are expensive to make, heavy to transport, and nearly useless as a medium of exchange. And still we can't get rid of them! If we can't even break our penny habit, how likely is it that we'll be able to shed our reliance on cash more broadly?

Cash's magic spell begins with the penny. You're right: if we can't even nuke the penny, doing away with cash sounds rather quixotic. And losing the penny is going to be especially hard during the term of a President from the Land of Lincoln. (You may have seen recently that the President wants the Treasury to look into making pennies out of cheaper materials, precisely because of this cost imbalance. Talk about an inability to see the forest through the trees.) All of that being said, I'm still hopeful that cash's death by 1,000 cuts is still on course, thanks to emerging technologies and alternative currency innovators. It's not so much that we will actively do away with pennies and cash in other denominations. It's that cash will get pushed so far to the margins that people won't want it anymore. Think of how little we use it already. Illicit transactions notwithstanding, when was the last time you or other PinkBlog readers used cash for any sizable purchase or payment?

What's the most surprising thing you learned about money – past, present, or future — while researching your book?

I was taken aback by how vehemently so many people oppose the idea of doing away with cash. For crooks, tax evaders, or individuals who want to buy porn in secret — I get it. What I'm talking about are people representing a broad spectrum of viewpoints, yet all converging on a defense of cash that is sometimes rational, other times not at all. ACLU types worry about threats to privacy resulting from an entirely digital money system; right-wingers ascribing to the get-government-off-my-guns-and-cash dogma obviously loathe the idea; and even everyday folks who just feel this kind of vague ambivalence about giving up on money in its tactile form. They know the paper and metal representations of US dollars aren't in and of themselves of worth. But they don't care. They still like them.

After reading the book, I'm convinced. Cash costs too much in terms of time, materials, security, transportation, you name it. Tell us what a future without money will look like, and what's one step a PinkBlog reader could take today to help make that future come true as quickly as possible?

The future holds a phantasmagoria of value options, with various currencies all exchangeable and trade-able in real time via your mobile phone. What can you do to nudge things along? Be like an airline! To avoid the high costs of cash, most major airlines have stopped accepting paper money for payment during flights. By doing so they have chipped away, ever so slightly, at the fungibility of cash. One of cash's historical — and, to a large extent, persisting — advantages is that it can be used across almost all uses because nearly everyone accepts it. But that doesn't have to be so. Look at how many restaurants and other businesses refuse to accept plastic because the proprietor doesn't like the fees. If refusing to accept cash strikes you as too extreme, or possibly too hazardous to your bottom line, consider encouraging other forms of payment by offering a discount, for instance, to people who pay with electronic funds, thereby helping you reduce the need for using–and paying to use–cash.

February 23, 2012

How to say No . . . especially to things you want to do

Last night, I had a breakthrough: I realized that personal productivity is the new dieting. (Like all evening epiphanies, this one is subject to future revision, refinement, and rejection.)

Here's what I mean.

A century ago, America didn't have much of a weight loss industry. Why? Lack of demand. Back then, calories were generally scarce and expensive. As a result, few people had the luxury to overindulge — which meant that waistlines didn't expand and the Dieting Industrial Complex couldn't exist.

But then, over the next few decades, a funny thing happened: The economics flipped. Calories became abundant and cheap. In this new environment, people, driven by genes programmed to accumulate those calories, did overindulge — which delivered lots of new customers to a once-tiny industry and presented our society with clutch of unexpected problems (obesity, diabetes, etc.)

Personal productivity has followed the same path.

A century ago, middle class Americans didn't have many options or much information. That enabled a simpler, though not necessarily better, life. So notwithstanding a few Ben Franklins and Napoleon Hills, we didn't need a ginormous industry devoted to helping us sort through our choices and refine our priorities.

But then, once again, things flipped. We now inhabit an environment (at least in much of the developed world) of abundant options and boundless, inexpensive information. That has triggered our dopamine-seeking instincts to pile too much onto our professional plates — which in turn has produced an entire infrastructure to help us avoid gorging ourselves.

The result is that the question that has bedeviled dieters now bedevils many of us in the option-rich, information-saturated Conceptual Age: How do we say "No?"

But as the wise Elizabeth Gilbert points out in the short video clip below, it's not just saying no in general or declining what we don't find interesting. It's saying no to things we actually want to do.

Here the dieting analogy clarifies the problem. It's easy for most of us to say no to a kelp and wheat germ smoothie. But saying no to the andouille cheese fries at Louisiana Kitchen? That's tougher.

And so the more I think about it, the more I realize that one of our big challenges (again, for those of us who lucked out, live in the developed world, and earn our living through something besides grinding physical labor) is this: How do we say no to things we want to do?

I don't have a good answer — but I have explored a few options:

I'm a devotee of Getting Things Done and that's helped a lot.

I believe in Tom Peters's idea of creating a "To-Don't" list.

Some folks use the equivalent of barricading the refrigerator with software like Freedom.

But I wonder if we could go further and help each other out — much as peer groups assist dieters. For instance, when someone who seems pretty interesting asks to meet for coffee or to talk on the phone for "only fifteen minutes," maybe the options aren't only to say Yes and feel like you've compromised your priorities — or No and feel guilty.

Instead, maybe there's something we could say that indicates that their request falls into the "I'd love to, but my health depends on saying no to things I want to do" category. Maybe a phrase ("cheese fries")? A new coinage ("R-No" — for "reluctant no")? A link to this blog post?

I wouldn't want to return to a world of limited options and pricey information any more than I'd like to return to a world of scarce, expensive calories. But I think we all need a little help dealing with our new circumstances and saying no to things that we want to do.

If you've got ideas on how to do that, leave them in the Comments section and I'll repost the best advice.

February 21, 2012

How to predict a student's SAT score: Look at the parents' tax return

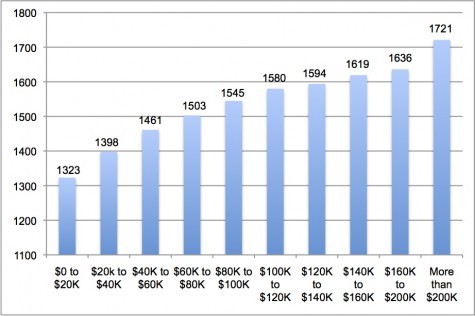

This weekend, triggered by a few readers who disagreed with my assertion that socioeconomic status is a huge driver of educational attainment and performance, I decided to respond the way any nerd would in my situation: I made a chart.

In a moment of Excel fervor, I took data from the College Board's 2011 Total Group Profile Report of college-bound high school seniors and plotted the mean combined (Reading, Math, and Writing) SAT scores for various income cohorts.

Take a look at the chart below. On the horizontal axis is family income. On the vertical axis is the combined average SAT score for students from families in each group. The general story is pretty simple: The higher the parents' income, the higher their kids' SAT scores.

(And this, sadly, is but one example. For a fuller account of the link between income and education, see the work of Duke's Helen Ladd.)

February 16, 2012

Eight brief points about "merit pay" for teachers

In today's Washington Post is another story about "merit pay" for teachers. But this one, by national education correspondent Lyndsey Layton, spends some space on my own thoughts on the topic.

For those new to the issue, or coming to the Pink Blog from Tweets about the article, let me summarize my views as succinctly as I can:

1. Some rewards backfire. Fifty years of social science tells us that "if-then" rewards – that is, "If you do this, then you get that" – are great for simple, routine tasks and not so great for complicated, creative tasks. Since teaching is creative and complex rather than simple and algorithmic, tying teacher pay to student performance (especially on standardized tests) flies in the face of the broad evidence.

2. Contingent pay for teachers just isn't effective. What's more, the specific evidence – a cluster of recent studies that have examined "if-then" pay schemes in schools – has shown them to be failures. See, for instance, this piece of research by Vanderbilt University or this one by Harvard's Roland Fryer or this study by Rand that prompted the New York City public schools to abandon its pay-for-performance plan.

3. Money is still important. The fact that "if-then" motivators often go awry doesn't mean that rewards in general or money in particular are bad. Not at all. The research shows that money matters. It just matters in a slightly different way than we suspect. Paying people unfairly — say, when Jane makes less than June for the same work — is extremely demotivating. And, of course, low salaries can deter some people from pursuing certain professions. Therefore, the best use of money as a motivator, at least for complex work, is to compensate people fairly and to try to take the issue of money off the table. That means paying healthy base salaries – and in the private sector, offering some non-gameable variable pay such as profit-sharing.

4. There's a simpler solution. My own solution for the teacher pay issue, which I've voiced many times both in writing and in speeches, is to strike a bargain: Raise the base pay of teachers – and make it easier to get rid of underperforming teachers. Not only is this approach more consistent with the evidence, it's easier to implement and doesn't require a new bureaucracy to administer. (To her credit, Michelle Rhee launched some efforts to move in this direction.)

5. We've got the wrong diagnosis. The notion that the central problem in American education is lack of teacher motivation is ludicrous. The vast majority of teachers in this country are some of the most hard-working, dedicated people you'll ever meet – folks who work their butts off in difficult conditions for little recognition. Pay for performance is a weak prescription in part because it's based on a faulty diagnosis.

6. What really ails us. The real problems, at least in my opinion, are twofold. First, the American education system itself, which is based on 19th century principles and structures, is woefully antiquated. Second, we're ignoring the issue of poverty and the overwhelming evidence that, absent comprehensive and expensive interventions, socioeconomic status is what drives much of educational attainment and performance. (This is one thing I actually liked about No Child Left Behind. It held someone's feet to the fire for schools that were criminally negligent in serving low-income kids.)

7. Teaching isn't investment banking. I find it peculiar that we single out teachers for "if-then" pay when we wouldn't consider it for other public servants. Should we pay police officers based on how many tickets they write or whether the crime rate in their district drops? How about compensating soldiers based on whether our borders have been attacked or how many of their colleagues have been injured or killed? Would legislators, who are behind much of the bonuses-for-test-scores push, ever agree to hinge their own pay on whether budget deficits rose or fell?

8. Turn down the heat, turn up the light. One thing I've noticed over the years is that the people on both sides of this issue are men and women with good intentions. Nearly everyone I've encountered is trying to do the right thing. Reasonable people can disagree about weighty matters. And most people are reasonable. The trouble is that much of our education policy — from how we finance it down to how we schedule buses — seems designed more for the convenience of adults than for the education of children. If we reckon with that unpleasant truth and have an honest conversation that places our kids at the center of our efforts, we can make a lot of progress.

February 15, 2012

Emotionally intelligent signage in burger joints

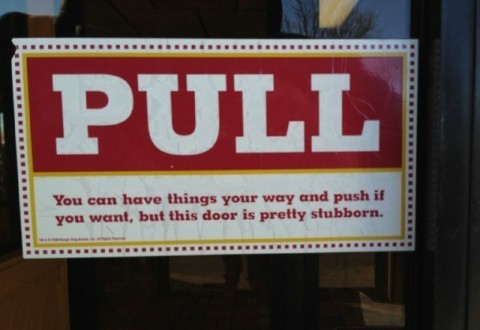

Emotionally intelligent signage! It's everywhere — including at lunch and dinner.

Stuart Ciske sends this example, which he saw at a Burger King in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Okay, maybe this time I won't have it my way.

Meanwhile, Jami Goldberg visited a Fuddruckers restaurant in Greensboro, North Carolina and spotted this — a nice touch for all those little, er, fuddruckers.

February 14, 2012

Should you drink bottled water? (And other questions for Charles Fishman)

Last year, my pal Charles Fishman wrote a really smart book about a really big subject: Water. To research his topic, which is both monumental and barely noticed, he journeyed from Las Vegas to New Delhi to Burlington, Vermont, to rural Australia to report on the state of H2O.

Last year, my pal Charles Fishman wrote a really smart book about a really big subject: Water. To research his topic, which is both monumental and barely noticed, he journeyed from Las Vegas to New Delhi to Burlington, Vermont, to rural Australia to report on the state of H2O.

Fishman learned that we've been living through what he calls "the golden age of water" — when, at least in the developed world, water has been unlimited, safe, and free. But that era is ending, he says. And throughout the world, we'll need new ways to source water, to price it properly, and use it less wastefully.

His book, The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water, comes out in paperback today. (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound). So I asked the man whom many call "Fish" to answer a few questions for PinkBlog readers.

Here's Fish . . . on water:

Bottled water seems to be the water issue people love to debate. You've been to Fiji, to San Pellegrino, to Poland Spring. So school us: Bottled water, okay or not?

If you pour a glass of Pellegrino from its beautiful green-glass bottle, two things are amazing: The water has traveled from the Italian Alps, across the Atlantic, to your café table. And the bottle it's shipped in weighs more than the water. If you buy a half-liter of Poland Spring at 7-Eleven for $1.29, you get four good swallows of water. You can then refill the empty bottle from your kitchen tap every day for 3,000 days — every day for 8 years and 3 months, long enough to go to college and medical school — before the tap water costs $1.29.

Bottled water is silly. Except after a natural disaster, no one needs a bottle of Evian or Fiji Water. It's an indulgence. But lots of things we enjoy are indulgences — Oreo cookies, French Merlot, Colombian coffee, "The Good Wife" on your iPad.

In the U.S., we spend $21 billion a year on bottled water. We spend $29 billion a year maintaining our entire water infrastructure — pipes, pumps, treatment plants. And bottled water can't rescue us in a crisis. When your house is on fire, you can't call Dasani.

So enjoy bottled water, if that's how you want to spend your money. But don't grump when the water bill goes up. That system needs attention and modernization, and compared to a bottle of Evian, it's a bargain.

A related question: You say in the book that water — the non-bottled kind — is too cheap and that its low cost hurts us. How can inexpensive water possibly be bad?

In the U.S., the average home water bill is $1 a day — $34 a month. In most of the country — and most of the developed world — that $34 doesn't even cover the cost of delivering the water, let alone maintaining and modernizing the system.

In the developing world, the poorest people pay an almost unimaginable price for water — women and girls have to walk to fetch it, often sacrificing all other activity. No schooling for the girls, no real jobs for the women. If they can walk to fetch that water, why can't a pipe be laid to bring it to them?

We've grown up expecting water to be cheap. Yet both cable TV bills and cell phone bills are typically twice what water bills are. A resource that is as cheap as water ends up used badly — misallocated, wasted, taken for granted, poorly taken care of.

If we all paid a little more for water, two things would happen: We'd all use it more smartly; and there would be enough money to keep the water system healthy, sustainable, and smart.

So if PinkBlog readers could take one action to move in that direction — to keep the water system, healthy, sustainable, and smart — what would it be?

Start simply. Dig out a couple recent water bills, and figure out how much water you are using each month and each day. When I started writing The Big Thirst, the Fishman family was using 350 gallons of water a day for four people. When I finished, we were using 250 gallons a day for four people — way under the US average of 100 gallons per person.

So figure out how much water you're using, and then get everyone together over dinner and see if you can cut your use just 10 percent — shower instead of taking a bath; water the lawn more carefully; don't flush the toilet when you pee; don't turn the faucet on full force if you're just rinsing dishes, washing vegetables, or washing your hands, times when volume doesn't matter. You'll be amazed how very small changes add up.

And one more thing: Turn off the lights, the TV, the computer monitor. Making electricity uses more water than anything in the US. When you turn off the lights, you're saving as much water as when you turn off the faucet.