Daniel H. Pink's Blog, page 5

November 8, 2012

The Hows and Whys of Gamification: 4 Questions for Kevin Werbach

Gamification. It’s one of the year’s top memes. The idea is that the more we embed systems — on the job, for our health, in social movements — with the mechanics and grammar of games, the more effective their participants will become.

Gamification. It’s one of the year’s top memes. The idea is that the more we embed systems — on the job, for our health, in social movements — with the mechanics and grammar of games, the more effective their participants will become.

Alas, like any white-hot meme, it’s often hard to sort the heat from the light. Thank heavens, then, for For the Win, a new book by Wharton’s Kevin Werbach and New York Law School’s Dan Hunter.

For the Win (Buy it at Amazon, BN, or IndieBound) is a smart and accessible guide to an intriguing subject. It’s grounded in research, but also includes plenty of case studies to bring the research to life.

Because Pink Blog readers are interested in new approaches to human motivation, I asked Kevin to answer a few questions about games, Wall Street, and presidential politics:

1. In your book, you refer to fun as “an extraordinarily valuable tool to address serious business pursuits.” Is gamification a new tool? Does its effectiveness stem directly from the rise of video games, or does it go back farther?

Companies consciously applying game thinking to their processes is new. And it’s happening now because of the rise of video games. Today’s digital platforms also make it possible to incorporate game elements into existing activities in ways that were never possible before. However, the concepts we describe in the book are really much older: what kinds of rewards and experiences motivate people, what makes a good game, and how fun fits into business. Think about it: Cracker Jack started putting toy surprises into every box exactly a century ago.

2. Seems like anytime a system includes a game, there’s someone gaming the system. Could you talk a little about the hazards of gamification?

That’s very important point. So many gamification advocates focus only on the positives. There is an entire chapter of For the Win about limitations and risks, and it’s something we mention throughout. One issue, as you point out, is that any time you create a game, someone will try to exploit the system. That’s not necessarily a danger, though, if you anticipate it. Those are your most engaged players, and you can often redirect their energy in a positive way, such as giving rewards for finding bugs in the game.

A second concern is that gamification can become a means of exploitation or manipulation. If making an activity game-like is a way to trick your customers or employees into doing something they wouldn’t otherwise want to do, you’re probably being unethical and it’s likely to harm your business interests in the long run. The approach we describe in the book is very different, because it’s built around the player’s interests.

3. You write, “The similarities between the interfaces of Wall Street trading terminals, enterprise collaboration software, and massively multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft are too striking to ignore.” For readers who may not be familiar with one or more of these environments, could you expand on the similarities?

Good information technology organizes and filters information to provide what the military calls “situational awareness.” Think about the Wall Street trader. Huge sums of money can hang on each decision. They have access to tons of resources: current prices, databases, market trends, analyst reports, and colleagues. Seeing the right information at the right time is crucial… but information overload is a constant threat. Trust me, being a raid healer in World of Warcraft feels the same way. Your group can die any time you make a wrong mouseclick. A WoW raid is a symphony of data flows: commands, notifications, performance stats, and multiple communications channels to choreograph up to 25 players. While most real-world business roles aren’t such a pressure cooker, good decisions at work always benefit from good information and good feedback. We can learn a great deal from the way game designers — and game players — build systems with same goals.

4. You write, “The 2012 American Presidential campaign represents the first time that gamification was used extensively in the political process.” Could you tell us more about that?

The campaigns on both sides, dating back to the primaries, have used mechanisms like badges and leaderboards to motivate volunteers and get out the vote. At one level, encouraging someone to “like” a candidate on Facebook or make a phone call isn’t all that different from encouraging them to endorse or buy a product. The widespread behavioral micro-targeting of potential voters also draws upon the concepts we describe in the book, such as player modeling and engagement loops. That being said, we won’t know all the details until after the election. Doing gamification well isn’t easy, and there many ways that selling a candidate is different than selling a soft drink. I expect we’ll see even greater and more sophisticated use of gamification in 2016.

Share on Facebook

November 5, 2012

Introducing . . . Drive Workshops

After more than a year of planning, I’m proud to announce that we’ve just begun rolling out a series of workshops built on the ideas in Drive and geared to help organizations put those ideas into action.

After more than a year of planning, I’m proud to announce that we’ve just begun rolling out a series of workshops built on the ideas in Drive and geared to help organizations put those ideas into action.

Check out the new Drive workshop web site for more details. As you’ll see, we’ve begun in earnest in Australia, where we’ve received a great response (as well as a prize for the most innovative HR product.)

Our first foray into the U.S. will be next month (December 4 and 5), when we’ll be holding an intimate workshop and train-the-trainer session in Washington, DC. People who complete this training will be licensed to deliver the workshop — and the only people eligible to deliver it — anywhere in America. It’s a great opportunity for free agent training and development consultants as well as for companies that want to equip their internal trainers with smart, practical ideas for boosting engagement.

Again, check out the site or this PDF brochure. And if you’ve got any additional questions, just email Andrew Greatrex, one of the entrepreneurial forces behind the venture.

Share on Facebook

October 31, 2012

The best 82-minute movie on mastery I’ve ever seen

I don’t get to see a lot of movies these days — and it’s almost unheard of that I’ll watch one twice. But this weekend marked my second viewing of the short documentary film, Jiro Dreams of Sushi. If you’re interested in the alluring, frustrating, asymptotic pursuit of mastery, this is movie is a must-see.

The film tells the story of Jiro Ono, an 85-year-old chef who runs Sukiyabashi Jiro, a sushi-only restaurant in Tokyo that has 10 seats — and 3 Michelin stars. Ono is obsessed with his craft, so much that sushi ideas come to him in his dreams. And while his obsessiveness has costs — for instance, his relationship with his sons, who’ve followed him into the family trade — it is also inspiring.

A few choice quotations:

“Once you decide on your occupation… you must immerse yourself in your work. You have to fall in love with your work. Never complain about your job. You must dedicate your life to mastering your skill. That’s the secret of success… and is the key to being regarded honorably.”

“I’ve never once hated this job. I fell in love with my work and gave my life to it. Even though I’m eighty-five years old, I don’t feel like retiring. That’s how I feel.”

“I do the same thing over and over, improving bit by bit. There is always a yearning to achieve more. I’ll continue to climb, trying to reach the top, but no one knows where the top is.”

The film is available on Netflix and on DVD. You can find out more on the movie’s website.

Share on Facebook

October 26, 2012

4 more emotionally intelligent signs

I haven’t been blogging much the last few weeks because I’ve been putting the finishing touches on a new book, which will be out at the end of the year. (Pre-order now. It’s worth it. I beg you.)

But the mailbag is always brimming with emotionally intelligent signage, so I’ve plucked four recent reader submissions that show some interesting examples of the crafty ways signs can attempt influence what we should and shouldn’t do.

Three of the signs direct viewers what not to do.

Don’t be a jerk on the road (via Jack Dorsey):

Don’t knock on my door (via Thad Gembczynski):

Don’t do anything stupid in a library (via Mike Stock):

And one tells us what we ought to do — albeit with a literary twist (also via Thad Gembczynski):

Share on Facebook

October 11, 2012

Ask Gretchen Rubin anything you want — only on Office Hours

Happiness. It’s what we all want, right? But what does it look like? How do we find it? And is the joy in the pursuit or in the realization?

Happiness. It’s what we all want, right? But what does it look like? How do we find it? And is the joy in the pursuit or in the realization?

For answers to these and other questions, tune in to Office Hours tomorrow (Friday, 12 October 2012), when our guest will be Gretchen Rubin, author of the blockbuster book, The Happiness Project, and the her newest work, Happier at Home.

Office Hours, of course, is our monthly radio-ish program that we call “Car Talk . . . for the human engine.”

Here are the instructions for participating:

When: Friday, 12 October 2012, 1pm, EST

How: Just dial (206) 402-0100, extension 203373 at the appointed hour to listen to the live interview live and to ask Gretchen a question.

For more on the program, including downloads of previous episodes, visit the Office Hours page.

Share on Facebook

October 10, 2012

Search Inside Yourself with Chade-Meng Tan

Chade-Meng Tan is an amazing guy. He started out as an engineer at Google, but his current title is Jolly Good Fellow with a job description that reads, “Enlighten minds, open hearts, create world peace.” As part of that mission, he developed a personal growth curriculum at Google called “Search Inside Yourself.” With his new book of the same name, he’s spreading that program to the whole world. (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound.)

Chade-Meng Tan is an amazing guy. He started out as an engineer at Google, but his current title is Jolly Good Fellow with a job description that reads, “Enlighten minds, open hearts, create world peace.” As part of that mission, he developed a personal growth curriculum at Google called “Search Inside Yourself.” With his new book of the same name, he’s spreading that program to the whole world. (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound.)

I find this combination of clear-sighted engineer and compassionate guru very intriguing, so I fired off a few questions for Meng. I think you’ll find something useful — perhaps life-changing — in his answers.

How did the Search Inside Yourself program come about? And what makes it different from other programs?

The main motivation for creating the Search Inside Yourself program is to create the conditions for world peace. I feel that if we have inner peace, inner joy and compassion on a global scale, it will create the conditions for world peace. In order to do that, I feel we need to align those qualities with success of individuals and companies. In other words, if we can help people and companies succeed in a way that inner peace, inner joy and compassion are the necessary and unavoidable side effects, then those three qualities will spread. I feel the way to achieve that is with an effective curriculum for emotional intelligence for adults. That is why I gathered a team of experts to create that curriculum in Google.

I think the main distinguishing feature of Search Inside Yourself is its emphasis on training core emotional skills. When you come across a program advertised as an emotional intelligence course, you might naturally assume it to be a mostly behavioral program, i.e., a program that tells you how to behave or to not behave in certain situations. Search Inside Yourself takes an entirely different approach. For example, it does not tell you how to react in an emotionally difficult situation; instead, it shows you how to train yourself to become calm and collected in an emotionally difficult situation so you can think clearly and choose for yourself how you want to respond. In addition, Search Inside Yourself has a strong scientific foundation, its methods are already shown to be effective in a work setting (in Google, no less), and it is taught in a highly accessible language.

Search Inside Yourself puts a strong emphasis on developing mindfulness. Why do you think we tend to avoid opportunities for mindfulness and sustained attention in favor of busy-ness and distraction? Is the reason ourselves or our circumstances?

Actually, I think we do engage in mindfulness and sustained attention a lot, but we only do so in circumstances we find enjoyable and rewarding, for example, when playing video games or buried in work that we enjoy or solving interesting problems. I think we avoid opportunities for mindfulness and sustained attention in favor of busy-ness and distraction when we consider what we are doing (or are supposed to be doing) to be a chore.

This insight suggests one strategy for practicing mindfulness meditation: try to make it not a chore. One skillful way for the beginner is to treat mindfulness as moments of rest for the mind. Rest your mind for a short moment by bringing a gentle attention to the process of breathing for maybe one breath, that is all. If you like, you can think of the mind as resting gently on the breath, whatever that means to you. If it helps, you can imagine the breath as the petal of a flower moving gently in the breeze and the mind as a butterfly resting gently on the petal.

The idea here is to have a lot of these micro mental rest breaks frequently. The best feature of this practice is it doesn’t require you to give up anything. You don’t have to stop working and go to a meditation room for an hour or something like that. You can take a micro break between tasks, when you are walking to the restroom, or at the beginning of every activity (for example, opening your lunch box or starting up your word processor). You can get some benefits of meditation for practically zero cost.

The key advantage of this practice is it never becomes a chore, because every time you do it, it feels rewarding (because it is restful), and one breath never gets long enough for mindfulness to become boring. Equally importantly, mindfulness practice is cumulative, so one second of mindfulness here and there adds up. Perhaps most important of all, if you do it frequently enough, mindfulness becomes a mental habit, and when that happens, you may be ready to do formal mindfulness meditation for long durations and not feel intimidated.

You write a great deal about listening — a skill that I think is poorly developed in most of us, in part because nobody ever really teaches us how. What are one or two listening exercises that Pink Blog readers might enjoy and learn from?

There is a very simple and beautiful practice called Mindful Listening that improves your listening skills and is almost guaranteed to improve your social life and the quality of your marriage.

The practice is very simple: as you listen, give your full moment-to-moment attention to other person with a non-judging mind. That is all. Every time your attention wanders away, just gently bring it back.

Think of this practice as offering the speaker the gift of your attention. When we give our full attention to somebody, for that moment, the only thing in the world that we care about is that person, nothing else matters because nothing else is strong within our field of consciousness. There is no greater gift.

In our class, we do a formal version of this practice as an exercise. We pair up participants and have them speak to each other in monologue for three minutes each. We frequently hear people telling us, “I got to know this person for six minutes, and we are already friends. Yet there are people who have been sitting in the next cubicle for months, and I don’t even know them.” This is the power of attention. Just giving each other the gift of total attention for six minutes is enough to create a friendship.

Share on Facebook

September 27, 2012

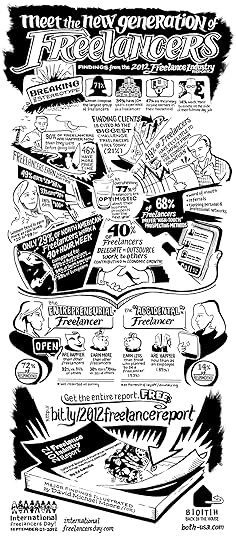

How are free agents doing these days?

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, I wrote a book about the rise of people working for themselves.

A lot has happened since then — a historic recession, the emergence of widespread broadband, the explosive growth of smart phones, the further erosion of job security, lower barriers to entry for small entrepreneurs, and so on — that has reinforced the underlying trends.

But for a clear and illuminating look at the current state of one group of independent workers, check out Ed Gandia’s 2012 Freelance Industry Report. Or if you’re too swamped to read the whole thing, look at this cool graphic summary of its main points:

Share on Facebook

September 12, 2012

Friday on Office Hours: Why do some kids succeed and others fail?

That’s the question at the center of a fascinating new book by New York Times Magazine and This American Life contributor Paul Tough. It’s called How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound). And Tough will be talking about it, and taking your questions, on the Friday edition of Office Hours, our monthly radio-ish program that we call “Car Talk . . . for the human engine.”

That’s the question at the center of a fascinating new book by New York Times Magazine and This American Life contributor Paul Tough. It’s called How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound). And Tough will be talking about it, and taking your questions, on the Friday edition of Office Hours, our monthly radio-ish program that we call “Car Talk . . . for the human engine.”

The book takes on what Tough calls the “cognitive hypothesis,” the idea that success hinges on mental processing speed and traditional brainpower. Instead, citing lots of interesting research, Tough shows that “non-cognitive skills” – perseverance, optimism, self-control, and so on – are actually what matter most.

To listen to an interview with Tough – and to ask him any question at all about kids, education, or your own career – tune in this Friday September 14 at 1pm, EDT.

Just dial (703) 344-2171 x203373 at the appointed hour to listen live and participate in a lively back-to-school conversation about preparing our kids and ourselves for the future.

Share on Facebook

September 10, 2012

Obama and Romney in a word

In a survey last week, the Pew Research Center asked a question whose form I’ve come to find interesting and useful: “What one word best describes Barack Obama/Mitt Romney/Joe Biden/Paul Ryan?” (As it happens, in my upcoming book, I use this type of question to show what people really think of sales.)

The answers to these questions are revealing in a way that other types of polling often are not. For instance, a quick look at the responses for Obama (below) and Romney (below that) reveals the amount of vitriol coursing through the election of 2012. ”Socialist,” “loser,” and “sh**” for the incumbent; “liar,” “jerk,” and “crook” for the challenger. And the responses for Biden and Ryan show that the former has an image problem and the latter, at least in my opinion, has gotten an easy ride so far in the campaign.

Prediction: The one-word method will become more prevalent, especially as data meisters collect truckloads of linguistic information from social networks.

Prediction: The one-word method will become more prevalent, especially as data meisters collect truckloads of linguistic information from social networks.

Share on Facebook

August 30, 2012

The Storytelling Animal: 4 questions for Jonathan Gottschall

Have you heard the one about . . . ?

Have you heard the one about . . . ?

Chances are, by the time you’ve reached this blog post, you’ve already heard dozens of stories in your day. Before you go to sleep, you’ll encounter dozens more. And you might desire some of these stories so deeply that you’ll pay for them.

As a species, we’re addicted to stories. But why? A terrific new book explains our strange narrative compulsion. It’s called The Storytelling Animal. (Buy it at Amazon, BN.com, or IndieBound.) And it’s a page-turner itself. In fewer than 300 pages, Jonathan Gottschall traces the cultural and scientific connections between story and the human brain, touching on nearly every facet of society long the way. (You can get a sneak preview in his excellent 80-second trailer.)

My interest in the power of story goes back a long way, so of course I had a few questions for Jonathan about what he’s learned on the subject:

You make a very convincing case about our species-wide addiction to stories. And yet so much of the time we spend immersed in story, whether reading novels, watching movies and TV, playing video games, or daydreaming, is characterized as “escapism” or “wasting valuable time.” Can you explain this paradox?

We love stories. We are enormously fascinated by the fake struggles of fake people. But the love is mixed with a little Puritanism: If it feels so good, it can’t be entirely good for us. So, for centuries we’ve worried not only that stories waste our time but, worse, that they promote laziness and moral corruption. I think this worry is misplaced. My book argues that stories—from conventional fiction to daydreams—are an essential and wholesome nutrient for the human imagination. Stories help us rehearse for the big dilemmas of life, bring order to the chaos of experience, and help unite communities around common values. We shouldn’t feel guilty about our time in storyland.

As you say in your book, storytelling permeates the business world — a sales pitch is a very short story, a presentation is a longer one, and of course we tell motivating stories to each other all the time in the workplace. Do you think this has always been so? Have business and commerce always been so storyfied? Is it changing?

There are two basic models of human nature in the business world. The Homo sapiens model assumes that it’s human sapience—wisdom, intelligence—that really sets our species apart. Based on this model, the best way to achieve business goals is to crunch numbers, lay out facts, and wait for rational actors to flock to your point of view. This is the traditional model. But a new model of human nature is emerging to complement—not replace—the traditional model. This is what I call the Homo fictus (fiction man) model of human nature. This model acknowledges that humans are creatures of emotion as much as logic, and that facts and arguments move us most when they are embedded in good stories. The world’s priests, politicians, and teachers have always known this by instinct, and so have the world’s marketers. What’s different now is a move to take storytelling beyond marketing and into all sectors of the business world that involve communication and persuasion. Storytelling is increasingly seen as an essential business skill.

That makes sense. In fact, you refer to commercials as “half-minute short stories,” and offer the Jack Link’s Beef Jerky ads as an example: “[They] say nothing about the product, by the way. They just tell stories about beef-jerky-loving guys who foolishly harass an innocent Sasquatch and earn a violent comeuppance.” Nothing about the product? How does that work?

Imagine you are a beef jerky marketer trying to take your relatively obscure brand to the top. What can you say about your product to set it apart from other brands of dried, salted beef? You could claim that your jerky is very tasty or healthy, but that will excite no one. So Jack Link’s just decided to tell the coolest and funniest stories they could, with the jerky appearing in the stories only as product placement—in exactly the same way that a Coke can might show up in a sitcom. This attempt to create a positive emotional connection with consumers worked big time. People liked the commercials so much that they went out of their way to watch them many millions of times on YouTube and to pass them around on their social networks. As a result, Jack Link’s is now a brand that most of know and think about positively.

What is one thing readers of this blog could do — today — to put what you’ve learned about the power of stories into action in their lives?

I’d like readers to take a moment (go ahead, do it right now) to marvel with me about the role of story in human life—from dreams, to reality shows, to urban legends, to religion, to pop songs, to the life stories that define our personal identities. For humans, story is like gravity—it’s this powerful and all-encompassing force that we hardly even notice because we are so used to it. But gravity is influencing us all the time, and story is too. Most of us think that our time in the provinces of storyland doesn’t shape or change us. But research shows that story shapes humanity at the historical, cultural, and personal levels. Story isn’t a frill in human life—something we do just for kicks. Story is a vastly powerful tool. By educating ourselves about story, we can use to learn that power in our own lives.

Share on Facebook