Some current game economics

Recently I was over on The Ancient Gaming Noob blog, where a discussion broke out on all the recent discussions about lootboxes, game development costs, game pricing, microtransactions, and all the rest. In particular, it was prompted by this video:

Despite the title of that video, games are indeed plenty expensive to make, and more specifically, they’re definitely too expensive to make without the revenue brought in by all this upsell stuff.

But the reasons why are complicated, and worth explaining in more detail. So I did, in comments on that blog, and the replies there suggested that I needed to make a blog post of it.

So here it is, basically a fix-up post, and not up to my usual essay standards, being as it is cobbled together from several impromptu comments. Bold text is comments I was asked or replied to.

First off, to address some of the figures in the video: cost of goods is not the same thing as cost of development. I’ll share some figures for that later on, but I think that by and large the public doesn’t really know how much games take to make.

Is it “too expensive”? Well, that’s a value judgement. We could look back at the history of studios that overextended and failed, and notice that it sure seems to be a high-risk business. But restaurants are a high-risk business too.

So question one: How many studios fail because video games are “too expensive to make” versus having a bad business plan or unrealistic expectations? (Or just a bad game?)

There is no question that there are plenty of studios that overspend. And yes, restaurants are extremely high risk businesses. But restaurants mostly compete on fixed costs — ingredients are largely the same for everyone, and barring something weird, their prices change at the rate of inflation. Games, not so much; every year a game that is competitive costs more to make.

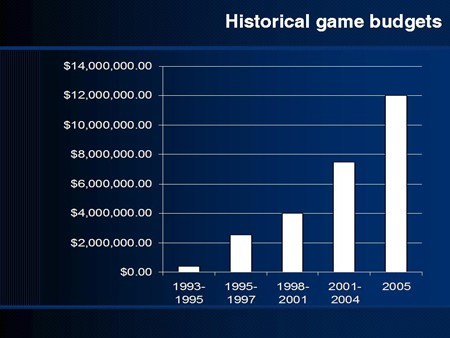

Data from 2005.

I did a talk back in 2005 about this. It’s here: https://www.raphkoster.com/games/presentations/moores-wall-technology-advances-and-online-game-design/ You can find graphs in there of the rise in costs for games. In short, it’s been an exponential curve for a few decades now. In 1995 it was around $2m to make a top-notch, AAA game. In 2000, it was more like $4m. In 2005, it was $12m. In 2010, $40m. In 2015, $120m or more. The biggest games are costing north of a quarter billion dollars to make. These figures, by the way, are already adjusted for inflation, and don’t include marketing money.

In terms of raw data generated — literally, the number of bytes the game takes up — we can easily see that dev teams have to generate many orders of magnitude more bytes than they used to. Voice and artwork have absolutely skyrocketed.

The result: a game like Assassin’s Creed has a staff of 1500 at seven studios in five countries.

Through it all, games mostly have sold for $60. Which used to be the equivalent of $100, because of inflation. Only today, thanks to Steam sales and the like, games actually sell on average for less than full retail.

The key thing to understand is that the public doesn’t buy B games. A game with stellar gameplay and less than state of the art graphics is generally simply left on the shelf. Yes, indie games with distinctive art have managed to break through so everyone will cite counterexamples, but looked at statistically, it’s something like 99.9% don’t. The average game on mobile makes somewhere between $0 and $100 total ever — and the typical game makes nothing. The average sales across all games on Steam is only 32,000 copies — that’s including all the hits that sell tens of millions. Metacritic scores show that you basically have to be up there at 85+ to be viable, and it’s very hard to get that without state of the art tech and visuals.

“Too expensive” isn’t a measure of just cost though, it’s a measure of risk. As costs have risen, we have seen massive consolidation across the industry. There used to be over 20 publishers of AAA games in the 90s. There also used to be dozens of third-party studios. As costs have risen, third parties have either died when they overextended trying to reach the quality bar, or they were absorbed by the larger companies. Publishers overextended by banking on major franchises, and when one didn’t hit, went away.

This cycle tends to reset only when new technology platforms come along that don’t let you do expensive productions because they don’t have the graphics horsepower. Mobile was like that, so was Flash gaming. But as soon as you can overspend on graphics, it becomes mandatory, and then the spiral starts. Early MMOs was like this — Ultima Online cost only a couple of million, Star Wars Galaxies under $20m, Sims Online and WoW north of $80m. Facebook games like Cityville cost more than UO to make! I wrote some about that in my post “An Industry Lifecycle.”

Basically, there isn’t a good business plan. There aren’t any realistic expectations. Any sane business person would say “don’t make games.” You can see this in MMOs now — where just getting 100k people subbing to something ought to make a highly satisfactory viable business… but go look at player reactions to visuals that aren’t at the absolute top end.

This is why service games — which reduce volatility and drive customer lock-in — help. And why free to play — which lowers marketing costs, hugely expands audience, eliminates price sensitivity, and removes spending ceilings — makes a difference. Bigger bets, fewer games, and try to make a service with microtransactions. It’s the only sensible way to play in the market if you have money.

If you don’t have money, the sensible thing to do is to make as many cheap small games as you can and hope one hits big and goes viral, so you have money and can switch to making a service-based game, or just keep making small ones. Just don’t switch to making a single bigger game that isn’t a service, because if it fails to hit, you’re dead. And it takes money to even make the public aware of your game. Marketing costs are huge. These days, $85m for marketing an AAA game isn’t a crazy figure. That would buy you four SWGs.

None of this is helped by the fact that the overall ecosystem has also changed a lot in many ways, which I wrote about in my post “The Financial Future of Game Developers.”

When games are cheaper to make, we get indies and creativity and explosions of awesome in the market. When games are expensive to make, we get predatory business models, sequels, and clones. People are complaining about predatory business models, sequels, and clones — so, games are too expensive.