“A grey cloak and an umbrella”

Today’s guest post is on Bleak House, by Charles Dickens. My high school friend Maggie Arnold has contributed several wonderful guest posts for my blog over the years, most recently on Jane Austen’s Persuasion, and I was very happy that she agreed to write a guest post for this new series in which I ask friends to recommend some of their all-time favourite books, and/or books they’ve read recently.

The Rev. Dr. Maggie Arnold is the Rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Cohasset, Massachusetts. She lives with her husband Christopher, and her children Rose and Clara, as well as their dog and cat. Maggie studied printmaking and bookbinding before going on to seminary and doctoral work in the religion of the Early Modern Period. Her book, The Magdalene in the Reformation, was published by Harvard University Press in 2018. She is currently working on a history of the Boston Episcopal Charitable Society, the second oldest charity in the United States.

I took this photo of Maggie’s book next to a gorgeous print she created when she was in art school and gave to my husband and me as a wedding present.

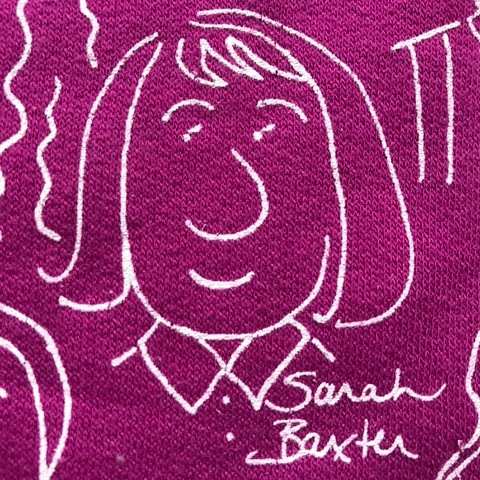

Maggie and I met on the first day of grade eleven in Halifax, and have been friends ever since. For six years, when we were both living in the Boston area, we were able to see each other relatively often, and in the years since my family and I moved back to Canada, we’ve been grateful for many visits in both Nova Scotia and Massachusetts. Back in 1991, Maggie designed a sweatshirt featuring images of the members of our (very small—there were fourteen of us!) graduating class. Now that I’ve shared a recent photo of her with you, I thought I’d also add the sketches she drew of the two of us when we were seventeen. My daughter is currently a student at the same school, and I keep threatening to embarrass her by wearing this old and beloved sweatshirt to an event—maybe next year’s gala fundraiser??

Please join me in welcoming Maggie!

I was so excited when Sarah asked me if I would consider writing a post for this series! I have used books therapeutically for years. A favorite author’s voice can be a way to turn my mind along better channels, if I have gotten into a muddy rut of self-pity or confusion. Jane Austen, for example, always gives me a sense of perspective: humour and also the goal of a life well spent, measuring one’s words and offering the best of one’s self to the relationships that mean most: our family and dear friends, the community around us. C.S. Lewis helps guide me back to the basics of Christianity, a no-nonsense approach to being on a journey with and toward God, staying humble and avoiding the pitfalls of trendy ideas.

One of my most beloved authors is Charles Dickens, whose compassionate vision seems to comprehend every story, every kind of life—urban and rural, male and female, rich and poor, generously busy and sadly constricted. His wide-ranging narratives encourage a curiosity about the human experience which I find deeply faithful. The worst sin, for Dickens, is indifference, and he does the work of combating that temptation for us; who could be indifferent to portraits drawn with such a knowing eye?

Sometimes I go to a cherished book seeking renewal for mind and spirit, but often what I need is more mundane, inspiration for the repetitive tasks of daily life as they add up over time. Dickens’ Bleak House contains multitudes, but at its edges is one small family and their home. We see them only briefly, introduced in the chapter “More Old Soldiers Than One,” but their effect on me is always so invigorating, like a breath of sea air. Mr. and Mrs. Bagnet were soldiers of empire, and are only recently settled in England after a career abroad. The names of their daughters, Quebec and Malta, testify to their birthplaces in far-flung outposts during the course of Matthew Bagnet’s military career (their son, “young Woolwich” indicates their retirement to London).

Despite Matthew’s service, it is Mrs. Bagnet who takes the commanding role in the family, and we see her strong but gentle husband deferring to her opinion on every question, as he admits, “It’s my old girl that advises. She has the head.” She herself is a marvel in nineteenth-century literature (or any literature, really), a middle-aged woman who is admirably resourceful, crisply efficient, cheerful and loving, devoted to the care of her family and yet neither officious nor resentful. Her presence in the book provides an antidote to the character of Mrs. Jellyby, also a fixture of British imperial culture. Where Mrs. Jellyby’s charitable projects for African orphans cause her to neglect her own children and household to the point of endangering her family and guests, Mrs. Bagnet capably sets her sights on what is near and dear. As a result, her home is a place of welcome refuge for the troubled Mr. George, her husband’s friend and fellow officer.

Her appearance speaks of the outdoors, “freckled by the sun and wind,” and her only ornament is her wedding ring, betokening her commitment to her marriage and its offspring. She looks after their finances and feeds her family a nutritious, frugal diet, as Mr. George recalls, “I never saw her, except upon a baggage-wagon, when she wasn’t washing greens!” Their home is simply furnished “and contains nothing superfluous, and has not a visible speck of dust or dirt in it.” The cleanliness and order, according to her “exact system,” are the manifestations of her good sense and thoughtful provision for her family. Her daughters are learning to read and to sew, accruing wisdom both intellectual and practical, Woolwich plays a patriotic fife, and they all help their mother with the domestic chores. Elsewhere we learn more of her history, and how she has been able to make a home anywhere she has traveled, which she has done independently, “with nothing but a grey cloak and an umbrella.”

Possessed of a sterling integrity that has stood the test of time, Mrs. Bagnet is untarnished by the world’s corruption, growing older with her husband as they raise their children, yet remaining along with him, in Dicken’s judgment, “simple and unaccustomed children themselves” in the ways of greed and deceit. To gain experience while staying young at heart—that continues to be my hope for each day, as I try to care for my own family, making a home and facing life’s challenges.

Mr. George and Matthew Bagnet together offer her the ultimate praise: George remarks that she looks as fresh as a rose, and as sound as an apple. “The old girl,” says Mr. Bagnet in reply, “is a thoroughly fine woman. Consequently, she is like a thoroughly fine day. Gets finer as she gets on. I never saw her equal.”

Here are the other guest posts Maggie has written for my blog over the years:

“What Women Most Desire: Anne Elliot’s Self-discovery” (for my blog series “Youth and Experience: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion”)

“Emma Woodhouse as a Spiritual Director” (for my blog series “Emma in the Snow”)

“‘Born again’: Valancy’s Journey from False Religion to True Faith” (in L.M. Montgomery’s novel The Blue Castle)

“Discerning a Vocation in Mansfield Park—But Whose?” (for my blog series “An Invitation to Mansfield Park”)

Previous posts in this series featuring book recommendations:

“Reading Close to Home,” by Naomi MacKinnon

“What is Said and What is Not Said,” by Jill MacLean

“Words that Heal,” by Renée Hartleib