Book Review: The Picture of Dorian Gray

I had super-high expectations when it came to reading The Portrait of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. I was loving the creepy, Victorian/Gothic vibes as well as the idea that a painting was aging while the model remained ageless. (Hope I didn’t spoil anything, but at this point I feel like everyone knows at least this much, though the original readers would have had more suspense about what was going on). While I did enjoy reading it and would recommend it, it was structured in a way that gave a bumpy ride, plotwise. Sometimes it was a bit slow (though at the beginning I was enjoying Wilde’s wordsmithing and the luxurious, Gatsby-esque aura he was creating), and then sometimes it just leaped over things. (There was an entire section detailing Dorian’s hobbies through the years that just about killed me. I skipped over whole paragraphs.) While the plot is the point of the story, it is an extremely simple one, leaving me wanting for more layers. But it’s a classic, forward-thinking for its time, and a short, almost-creepy read.

Dorian Gray open up with two men who are not Dorian, though they get to talking about Dorian. One of the men is an artist and he has become obsessed with his newest model and has just completed his life’s masterpiece: a portrait of Dorian Gray. The other man has yet to meet Dorian, but soon does, also becoming obsessed but throwing his obsession into influencing the young, innocent Dorian into using his beauty to become a rake and a rascal and introduces him to many controversial ideas about the world, society, and humanity. When Dorian sees the portrait, he makes an off-handed wish that the portrait would age and that he never would. When the portrait is gifted to Dorian and he commits his first heinous sin, he discovers that wishes do sometimes come true, which means that he is free to live however he wants without consequence. And yet, the portrait haunts him…

I read this book because it was next on my Halloween reads list. It took me forever to review it because I finished right before I threw myself into Nanowrimo, which was followed up by a house full of flu (including me).

Okay, sigh. The whole story here hinges on the idea that sin makes a person ugly while innocence keeps them young and beautiful, essentially. The second part of that equation is less adamant than the first part. Well, quite frankly, while I do think that “fast living” and poor choices can lead to premature aging, illness and disease, etc., traditional ugliness in a particular person is a much more complicated matter than that. We all know those people who smoked like a chimney their whole lives and functioned completely normally until they died at like age 100. It’s not exactly the norm, but awful people (by which I am referring not to smokers, but people who behave terribly against others) can look dazzlingly beautiful, and some saints age quickly and aren’t exactly beauty queens. You might suggest that this is meant to be a metaphor in Dorian, that we are meant to read it as allegory, but this was an actual idea of the times which I have encountered in many Victorian novels—that you can tell what a person is like by their face and body. I call BS. But for Dorian Gray, a modern reader can read it like it is a fantastical element in order to make a point, especially since the novella is already magical realism. So do that, I guess.

So, apparently there were like 500 words that were cut from the original novella (without notifying Wilde) in order to make it more palatable to the ladies of the day. And apparently some of those words were references to homosexual romance (veiled, of course, as so much was in that era). While I wish Wilde had been left alone to tell his own story in the way that he saw fit, I am also not keen on making this an LGBTQ+ story simply because there is a lack of platonic relationships between same-sex peeps in today’s literature, and I found the themes of non-erotic obsession to be interesting (perhaps more interesting) than if they were sexual in nature. Then again, hearing a voice from the later 1800s presenting the tension and reality of either being gay or having homosexual desires would be interesting, too. And honest to Wilde’s intentions. For that, you can supposedly get a copy of the re-edited version with the text put back into it; you’ll find it by looking for the “original 1980 version” or “uncensored version.” I did not know this existed before I got my copy.

Also, I am not happy about the POV. True to the style of the times, it is omniscient third, and we spend most of our time zoomed in on Dorian and the rascally guy. The rascally guy, Wotton, was really annoying to me, and he is also prone to speeches. I don’t think we’re supposed to take everything he says as truth—quite the contrary—though Dorian falls for it and we’re left with nothing really to counter his ideas when they go especially off the rails. It made Wotton feel like the mouthpiece for Wilde, and maybe he is, but I definitely wanted to get cozier with some of the more peripheral characters and not hear so much from the lips of Wotton. It’s also the kind of story that could use a more intimate POV, which could be someone besides Dorian, like even a maid or a combination of his lovers or something. Yeah, I know, they didn’t do that kind of thing back in the day.

Blogger’s note: Wotton goes by both Harry and Henry. So confusing to me. And another note: this is a very masculine book; beware sexist off-hands. And he’s really hard on the lower classes.

Other than that, if you enjoy Gothic or Victorian literature, this is a little novella (originally commissioned for a magazine) that you will probably enjoy, especially if you like a) lush descriptions that really put you in a place and mood and b) The Great Gatsby and books like it. The writing style is a few decades older than F. Scott Fitzgerald, but it felt like a forerunner and also like the story and setting were giving off similar vibes. (Second time I used “vibes” in one review. Minus five points for me.) It’s not really creepy enough to make it a real Halloween read, but it’s a classic and a quick read which explores various ideas about beauty, morality, guilt, etc. and a peep into the elite/artist life of 1890s London and Paris.

Image from the New York Review of Books

Image from the New York Review of BooksOscar Wilde is a household name (at least if you are literary or a student), yet he produced his famous works in the last years of his life, and they are not many: The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Importance of Being Ernest, and perhaps An Ideal Husband. Besides Dorian Gray, his real claim to fame was a “new” type of comedy that he presented in these later plays, beginning with Lady Windermere’s Fan. Wilde was a society artist of import for most of his life, however, and lived among the elite and the artists, doing his Irish thing in London and basically being an aesthetic and living decadently, an editor and writing fairy tales, often counter-moral to the norms of the day. Though he was married with two children, near the end of his life he was tried and jailed for “sodomy” by a “friend”’s father. After serving his sentence, he spent the remainder of his days in Paris, bankrupt, trying to rise again as a writer, but died soon after of meningitis.

“…for there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about” (p6).

“But beauty, real beauty, ends where an intellectual expression begins” (p7).

“There is a fatality about all physical and intellectual distinction, the sort of fatality that seems to dog through history the faltering steps of kings” (p7).

“Your rank and wealth, Harry; my brains, such as they are—my art, whatever it may be worth; Dotian Gray’s good looks—we shall all suffer for what the gods have given us, suffer terribly” (p7).

“The commonest thing is delightful if one only hides it” (p8).

“…every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, to occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself” (p9).

“’Laughter is not at all a bad beginning for a friendship, and it is far the best ending for one,’ said the young lord, plucking another daisy” (p12).

“But I can’t help detesting my relations. I suppose it comes from the fact that none of us can stand other people having the same faults as ourselves” (p12).

“We live in an age when men treat art as if it were meant to be a form of autobiography. We have lost the abstract sense of beauty” (p15).

“The thoroughly well-informed man—that is the modern ideal. And the mind of the thoroughly well-informed man is a dreadful thing. It is like a brac-a-brac shop, all monsters and dust, with everything priced above its proper value” (p15).

“Music had stirred him like that. Music had troubled him many times. But music was not articulate. It was not a new world, but rather another chaos, that it created in us” (p22).

“But we never get back our youth” (p25).

“The life that was to make his soul would mar his body. He would become dreadful, hideous, and uncouth” (p28).

“Man is many things, but he is not rational” (p30).

“As long as a woman can look ten years younger than her own daughter, she is perfectly satisfied” (p50).

“Faithfulness! I must analyze it some day. The passion for property is in it. There are many things we would throw away if we were not afraid that others might pick them up” (p52).

“He says things that annoy me. He gives me good advice” (p58).

“A great poet, a really great poet, is the most un-poetical of all creatures. But inferior poets are absolutely fascinating” (p58).

“As it was, we always misunderstood ourselves and rarely understood others” (p60).

“Women defend themselves by attacking, just as they attack by sudden and strange surrenders” (p65).

“Children begin by loving their parents; as they grow older they judge them; sometimes they forgive them” (p68).

“To be in love is to surpass one’s self” (p69).

“When poverty creeps in at the door, love flies in through the window” (p69).

“Dorian is far too wise not to do foolish things now and again, my dear Basil” (p74).

“But I didn’t say he was married. I said he was engaged to be married. There is a great difference” (p74).

“And to be highly organized is, I should fancy, the object of man’s existence” (p75).

“The basis of optimism is sheer terror” (p76).

“’Women are wonderfully practical,’ murmured Lord Henry, ‘much more practical than we are’” (p78).

“When we are happy, we are always good, but where we are good, we are not always happy” (p79).

“Love is a more wonderful thing than art” (p85).

“…who were extremely old-fashioned people and did not realize that we live in an age when unnecessary things are our only necessities” (p94).

“There is a luxury in self-reproach. When we blame ourselves, we feel that no one else has a right to blame us. It is the confession, not the priest, that gives us absolution” (p97).

“Good resolutions are useless attempts to interfere with scientific laws. Their origin is pure vanity. Their result is absolutely nil” (p101).

“It often happens that the real tragedies of life occur in such an inartistic manner that they hurt us by their crude violence, their absolute incoherence, their absurd want of meaning, their entire lack of style” (p101).

“Conscience makes egoists of us all” (p103).

“I didn’t say I liked it, Harry. I said it fascinated me. There is a great difference” (p126).

“…perhaps in nearly every joy, as certainly in every pleasure, cruelty has its place…” (p127).

“…wondering sometimes which were the more horrible, the signs of sin or the signs of age” (p128).

“…he would think of the ruin he had brought upon his soul with a pity that was all the more poignant because it was purely selfish” (p128).

“…the remembrance even of joy having its bitterness and he memories of pleasure their pain” (p132).

“…the conception of the absolute dependence of the spirit on certain physical conditions, morbid or healthy, normal or diseased” (p133).

“…that pride of individualism that is half the fascination of sin” (p140).

“[Civilized society] feels instinctively that manners are of more importance than morals, and, in its opinion, the highest respectability is of much less value than the possession of a good chef” (p141).

“Dorian Gray had been poisoned by a book” (p145).

“Sin is a thing that writes itself across a man’s face. It cannot be concealed” (p148).

“My dear fellow, you forget that we are in the native land of the hypocrite” (p150).

“Each of us has heaven and hell in him, Basil” (p156).

“…the way people go about nowadays saying things against one behind one’s back that are absolutely and entirely true” (p177).

“Women try their luck; men risk theirs” (p178).

“’Women love us for our defects. If we have enough of them, they will forgive us everything, even our intellects’ …. / ‘Of course it is true, Lord Henry. If we women did not love you for your defects, where would you all be?’” (p178).

“’To be popular, one must be a mediocrity.’ / ‘Not with women,’ said the duchess, shaking her head: ‘and women rule the world. I assure you we can’t bear mediocrities” (p195).

“Actual life was chaos, but there was something terribly logical in the imagination. It was the imagination that set remorse to dog the feet of sin. It was the imagination that made each crime beat its misshapen brood. In the common world of fact the wicked were not punished, nor the good rewarded” (p198).

“Had it been merely vanity that had made him do his one good deed? Or the desire for a new sensation, as Lord Henry had hinted, with his mocking laugh? Or that passion to act a part that sometimes makes us do things finer than we are ourselves?” (p219).

There have been many adaptations of the book to movies, TV shows, and plays and musicals. The character of Dorian Gray has also been taken on by countless writers for books, movies, TV shows, etc., enough that he is usually considered one of the classic characters of the horror genre (with Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, etc.). Here are a few notable adaptations:

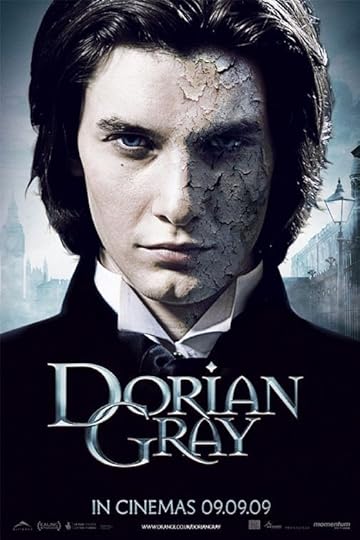

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.comSome of the classic adaptations of the book to movie have been popular, including The Picture of Dorian Gray (1915), The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1973 TV movie). A more recent adaptation of the book is Dorian Gray (2009), and I would like to check that out one of these days. I should have watched it in October. There is even a modernized version involving social media, The Picture of Dorian Gray (2021).

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.comAs for adaptations that go further afield and just grab the character to include him in another venue, there is The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003; a movie I have been meaning to see for some time due to the use of several Victorian horror characters), and Penny Dreadful (TV series, 2014-2016).

Phantom of the Paradise (1974) is supposedly a mash-up of Phantom of the Opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and even a little Frankenstein in a rock musical.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comThe Picture of Dorian Gray: A Graphic Novel is a highly rated version by Jorge C. Morhain and Martin Tunica.