“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

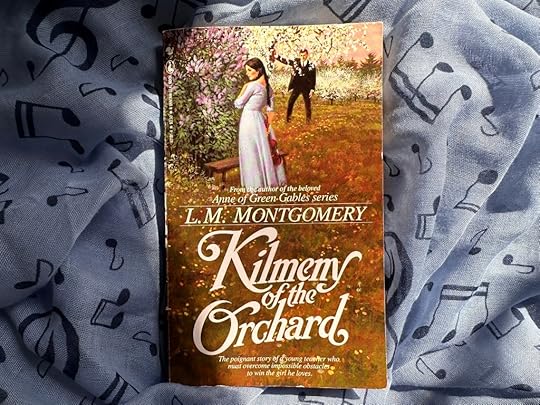

L.M. Montgomery’s third novel, Kilmeny of the Orchard, was published in 1910, following the phenomenal success of Anne of Green Gables in 1908 and Anne of Avonlea in 1909. Her publisher, L.C. Page, expected her “to produce one book after another at breakneck speed,” Mary Henley Rubio writes in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Although she would revisit—not always willingly—the world of Anne Shirley many times in the coming years, for this third book, Montgomery expanded a short story she had published between December 1908 and April 1909 in a magazine called The Housekeeper, a romance called “Una of the Garden.” Her hero, Eric Marshall, falls in love with a beautiful and talented violinist, Kilmeny Gordon, who plays pieces of her own composition in an old orchard not far from the house where Eric is boarding while he teaches at the local school in Lindsay, Prince Edward Island.

Please join my friend Naomi MacKinnon and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here. I’ll be back later this month with another post on the novel.

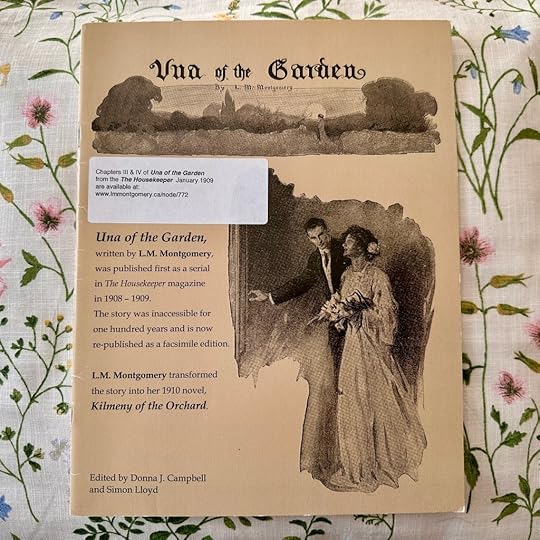

On a trip to PEI several years ago, I bought a facsimile edition of “Una of the Garden,” in which L.M. Montgomery is described more than once as “Author of Ann of Green Gables.” (No “e”! Unforgivable.) Her story appears alongside advertisements for Snider Pork & Beans (“People who can’t eat ordinary, indigestible, home-cooked Pork and Beans enjoy Snider’s”), Heatherbloom Taffeta Petticoats (“made in all the shades and stripes so modish to-day”), and Jell-O (“best for the whole family because it is delicious, pure, wholesome and nutritious”). When she revised and expanded the story, Montgomery changed the names of characters and places, including Una Marshall, now Kilmeny Gordon, and Eric Murray, now Eric Marshall. Neil Marshall, the orphaned son of “a couple of Italian pack-peddlers” who becomes Eric’s rival for the heroine’s affections, is renamed Neil Gordon. The setting is changed from Stillwater to Lindsay, and the garden is replaced by an orchard.

Montgomery was not happy about her publisher’s demands. Her original story was not long enough to please Page, “so I have had to re-write and lengthen it—a business I dislike very much,” she wrote in her diary in December 1909 (The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston). She had been working, she said, “until I would fairly feel faint with fatigue,” and she was afraid of the “terrible attacks of gloom and restlessness” that often tormented her. “If I can only keep physically well and nervously unbroken I shall not mind anything else so much.” Although Montgomery was tired, Rubio says that working on the novel served as a distraction, as she found that “writing could often help her block out worries in her real life. It was a pleasant way to escape.”

Montgomery wrote of Kilmeny that “It is a love story with a psychological interest—very different from my other books and so a rather doubtful experiment with a public who expects a certain style from an author and rather resents having anything else offered it.” Already she was facing the challenges of writing for an audience that was hungry for more Anne stories, and more books with a pastoral island setting.

In her new novel, she made PEI even more idyllic than in her first two “Anne” books. As Eric’s friend Larry West says in a letter when he is trying to persuade Eric to take his place as teacher in Lindsay for the last few weeks of the school year, “Prince Edward Island in the month of June is such a thing as you don’t often see except in happy dreams. There are some trout in the pond and you’ll always find an old salt at the harbour ready and willing to take you out cod-fishing or lobstering” (Chapter 2). The orchard, especially, is perfection:

Most of the orchard was grown over lushly with grass; but at the end where Eric stood there was a square, treeless place which had evidently once served as a homestead garden. Old paths were still visible, bordered by stones and large pebbles. There were two clumps of lilac trees; one blossoming in royal purple, the other in white. Between them was a bed ablow with the starry spikes of June lilies. Their penetrating, haunting fragrance distilled on the dewy air in every soft puff of wind. Along the fence rosebushes grew, but it was as yet too early in the season for roses. (Chapter 5)

As Elizabeth Rollins Epperly writes in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance, “Montgomery makes the story pleasing to read and lifts it briefly beyond formula with her loving descriptions of sunset and garden.” Many of the passages about the setting are lovely, but sometimes I found them excessive. For example, “most of the idyllic hours of Eric’s wooing were spent in the old orchard; the garden end of it was now a wilderness of roses—roses red as the heart of a sunset, roses pink as the early flush of dawn, roses full blown, and roses in buds that were sweeter than anything on earth except Kilmeny’s face.”

Kilmeny is beautiful—there’s no doubt about that in this novel. She herself doesn’t know it, however, because her mother broke all the mirrors in the house and did not allow Kilmeny to see her own face. Kilmeny has never been able to speak, and the cause of her disability is mysterious. Is she physically incapable of speaking, or has her fate somehow been shaped by her mother’s “sin” (as her Aunt Janet Gordon believes), or is there some other reason she lacks a voice? Elizabeth Waterston says in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that “the ‘psychological interest’ comes from the doctor’s theory of psychosomatic impairment caused by ‘trauma’ and his hope that Kilmeny may be shocked into a cure.”

I’ll write more next time about Kilmeny’s inability to speak. For now, I want to ask what you think of Kilmeny, Eric, and Neil, the descriptions of the landscape, and Montgomery’s “experiment” in this novel. Did you find Kilmeny formulaic, as many reviewers and critics have suggested? “For the first time,” Liz Rosenberg writes in House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery, “Maud’s work received negative reviews. One reviewer called it ‘a terrible specimen of the American novel of sentiment.’ Another said that the main character was enough to bring on ‘a bilious headache.’” Epperly says that “Everything in the novel belongs to formula,” including the character of Neil Gordon, the “dark, passionate, unscrupulous foreigner (Montgomery’s story makes unblushing use of xenophobia and bigotry).”

As I was reading the novel, for the first time since I was about ten or eleven, it occurred to me that while I found it engaging—and often disturbing—I probably wouldn’t have picked it up at all if it had been written by someone other than Montgomery. I wouldn’t say it gave me a bilious headache, but it isn’t my new favourite Montgomery novel, either. Even so, I’m finding it interesting to learn about how Kilmeny fits (or doesn’t fit) with Montgomery’s other novels, and where the novel falls in the development of her career. I wanted to reread this novel precisely because it doesn’t receive as much attention as the Anne and Emily books. And I was curious about the way Montgomery transformed “Una” into Kilmeny.

I came across this list of LMM books in my childhood library recently. I didn’t own Kilmeny of the Orchard (until I bought a copy a couple of months ago), and when I read it as a child, I must have borrowed it from the library. While I was sorting through notebooks and papers from elementary school, I also found this drawing of a bookshelf.

I’m keen to hear what you think—in the comments on this post, or on social media (Facebook; Instagram), or on your own blog—and I’ll look forward to continuing the conversation next week. Thanks for reading with us!

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

“I found this fairly twee, with an unfortunate focus on beauty (‘“Kilmeny’s mouth is like a love-song made incarnate in sweet flesh,” said Eric enthusiastically’), and marriage as the goal of life. But it was still a pleasant read, especially for the descriptions of a Canadian spring.”

More photos of spring in Kent, sent by my friends Sheila and Hugh Kindred:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them: