My title comes from Alice Munro’s afterword to L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, in which she writes of the experience of reading the novel for the first time at age ten:

In this book, as in all the books I’ve loved, there’s so much going on behind, or beyond, the proper story. There’s life spreading out behind the story—the book’s life—and we see it out of the corner of the eye. The milk pails in the dairy-house. Aunt Elizabeth pouring the tallow for the candles. The slightly repulsive splendour of the parlour at Wyther Grange. The corners of the kitchen at New Moon. What mattered to me finally in this book, what was to matter most to me in books from then on, was knowing more about life than I’d been told, and more than I can tell.

(From the New Canadian Library edition of Emily of New Moon)

Munro quotes from another edition of Emily of New Moon, which claims on the cover that in this story the heroine discovers she is not alone, and she says she disagrees with this assessment of the novel. She objects to the “familiar brisk assumption” that books are supposed to “spread messages, and that the messages are cheery and confining.” She says she doesn’t know what book Montgomery intended to write, but the one she did write “is surely one in which Emily finds that she is alone, that she has chosen her life without knowing that she was choosing it, and she’s exultant about the choice.”

Like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, who famously says “I care for myself” (Jane Eyre, Chapter 27), Emily Starr announces proudly, “I am important to myself,” after she’s been told she is “not of much importance” (Chapter 3). I like Munro’s word “exultant.” I was sad to hear of her death last month, at the age of 92, and I’ve been revisiting some of her writing and favourite quotations from her work.

I like what she says about how “Writing fiction is seldom something that has to be done that day.” In a 2005 essay called “Writing. Or, Giving Up Writing,” Munro says, “in order to have time to do my work I must continually refuse to do things that other people think perfectly reasonable and even obligatory for me to do, and sometimes I get mad enough to tear out my hair.” As she reflects on her decision to give up writing, she asks what made writing “irresistible” in the first place.

She says it isn’t the work or sending the work out or seeing it published or reading it to an audience or seeing it on a bestseller list or seeing it win a prize. Instead, she asks, “Isn’t the really good time when you are just getting the idea, or rather when you encounter the idea, bump into it, as if it has always been wandering around in your head?” She says, “It’s not the story—it’s more like the spirit, the centre, of the story, something there’s no word for, that can only come into life, a public sort of life, when words are wrapped around it” (Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke).

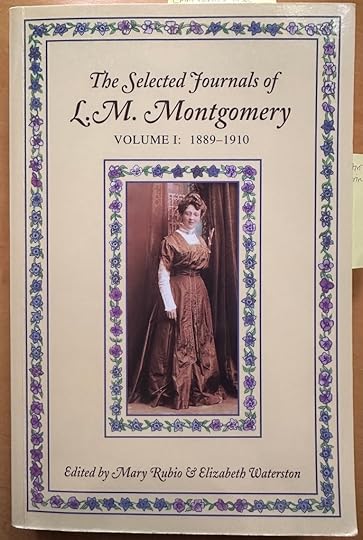

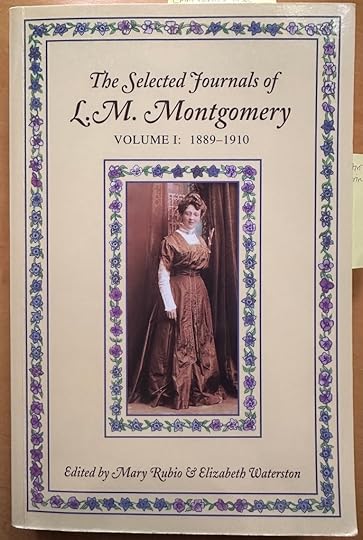

I’ve always liked Mary Henley Rubio’s story about the day she gave Munro a copy of the first volume of The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery in late 1985. Rubio says, “she looked at it for only a second to see what it was, and then, without missing a beat or without making any reference to Emily of New Moon, she responded by quoting the end of the novel: ‘I am going to write a diary that it may be published when I die’” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings).

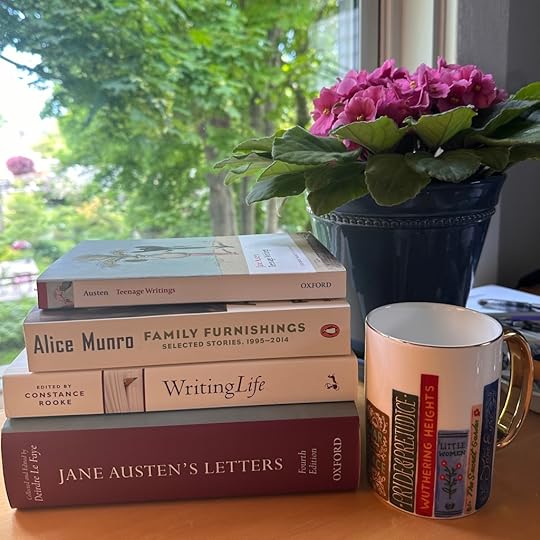

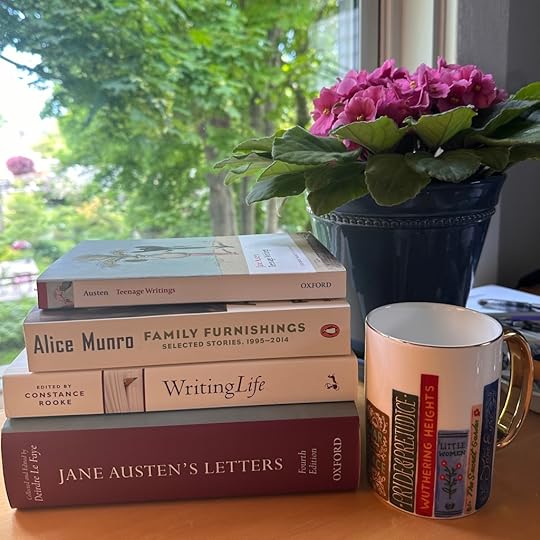

I’m in the middle of writing an essay for this year’s JASNA AGM in Cleveland, Ohio. It’s called “‘She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away’: Stealing Sources and Avoiding Consequences in Jane Austen’s Fiction,” and I’ve been turning to Munro for that as well. I’m intrigued by what the narrator says in her story “Family Furnishings” about how planning to write fiction is “more like grabbing something out of the air than constructing stories.” I’m also rereading essays by Margaret Drabble, Eudora Welty, and other writers, exploring Drabble’s claim that “The ‘writing life’ is a life of crime.” (Like the Munro essay I quoted above, Drabble’s essay also appears in Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke.) I’m especially interested in Austen’s heroine “The Beautifull Cassandra,” who steals a bonnet from her mother’s shop and runs off to seek her adventures.

If I start writing in detail about either the Beautifull Cassandra or Alice Munro’s stories right now, this will turn into a very long post. I’m tempted! It would be an excellent way to procrastinate. If I spent more time on Munro’s stories, I’d start with “Nettles,” one of my favourites. But I want to go back to working on my JASNA lecture, and so I’ll just add a wonderful quotation about Munro’s work from The Philadelphia Inquirer, and then I’ll end with some photos sent to me by my friend Sandra Barry.

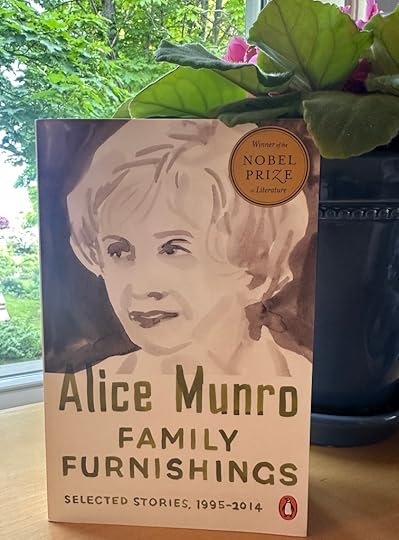

Munro was “A writer who slowly fashioned a house of fiction large enough for both a room of her own and all of her family furnishings—ensuring that she herself had space to maneuver while others still had plenty of space to stretch out and live. Those others include us, her very lucky readers.” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, quoted in Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014).

Photos by Brenda Barry, taken on a recent walk on a wetland trail in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. I’ll be back next Friday with details about my new blog series, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which launches on June 20th.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?” (Photos from my trip to Oxford, Mississippi)

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Thank you for introducing me to the Munro and LMM connection. I can't believe I had never thought of LMM's influence on Munro before, and of course it would be the Emily books Munro would quote from. Like many Munro-devotees, her passing (and a recent visit to Munro's Books) has led me to dive back into her work, but now I am tempted to reread the Emily books soon too.

Thank you for introducing me to the Munro and LMM connection. I can't believe I had never thought of LMM's influence on Munro before, and of course it would be the Emily books Munro would quote from. Like many Munro-devotees, her passing (and a recent visit to Munro's Books) has led me to dive back into her work, but now I am tempted to reread the Emily books soon too.