Sense and Sensibility in my most need, by Heidi LM Jacobs

At the risk of sounding too much like Marianne Dashwood, I feel compelled to admit I’m going through a rough patch. Still gutted from the loss of one parent several years ago, I’m confronting the mortality of the other and the inevitable letting go of the one home our family has lived in. I have seen countless friends and family members deal with this very thing. But having watched others navigate this difficult road doesn’t make it any less bewildering or any less real.

A late-night phone call from my brother and the hasty purchase of a one-way ticket to Edmonton in late April pushed this essay I’d promised to Sarah out of my head. By the time I looked at my planner last week, I realized the due date was hurtling toward me and the fear of missing this impending deadline sent me into a space of dread.

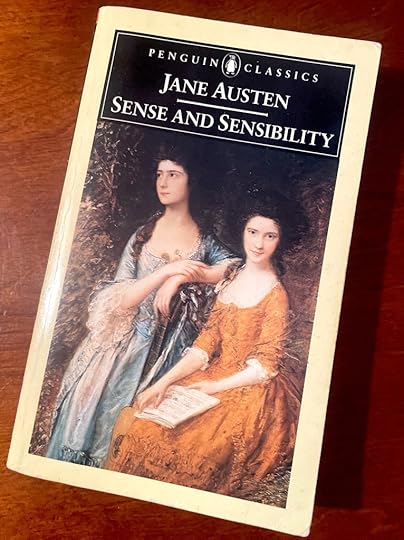

I dug out my prospectus and saw that I said I would write about how Sense and Sensibility was my gateway Jane Austen novel, purchased with a Christmas gift certificate from my Auntie Cathy at a Coles bookshop in Edmonton when I was the exact age of Marianne Dashwood. I am not sure why I selected Sense and Sensibility but this purchase changed my life’s course.

(From Sarah: This is the third guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I had been looking forward to writing this piece and had set aside the first two weeks of May for a leisurely reread of Sense and Sensibility and the following two weeks to craft my essay. I anticipated writing something lighthearted—maybe discussing my realizations that I’m now older than Mrs. Dashwood, whose existence as an interesting person was clearly over, or that the ancient, “infirm,” and flannel waistcoat-wearing Colonel Brandon was just on the wrong side of five and thirty. I also thought I might take my young self to task for remembering every detail of Willoughby’s carrying Marianne through the rain yet skimming over his reprehensible actions. For a time I thought Willoughby the best of all Jane Austen’s suitors because he read poetry and bought Marianne a horse.

Determined to meet my deadline, I picked up my original copy of Sense and Sensibility and sat at my desk with a pencil and notebook for several mornings in a row. Each morning, I quickly became distracted and put the book down to do other things. None of those early topics felt like what I wanted to write. I realize now that to read my original copy of Sense and Sensibility meant going back to being almost 17 and reading on the mid-century teak furniture still in my parents’ living room. I also read this book in my childhood bedroom that’s still filled with my books and those I gave my Mum over the years. In the foreseeable future, I know I will need to find new homes for all of the things that made our house home to us for so many years.

Unsurprisingly, more tears than words were generated at my desk. After the third morning of indulging my inner Marianne, I took on a decidedly more Elinor approach. I downloaded an audio book of Sense and Sensibility and went for a series of long walks. I was no longer reading the same pages as my young self, no longer smiling at what I’d underlined or starred: “It is not every one who has your passion for dead leaves” was a particular favourite (Volume 1, Chapter 16). By listening and simply letting the words fall over me as I walked through woods and neighbourhoods, along train tracks and the river, I was experiencing an entirely new novel.

In my first readings of this novel as a teenager, I saw only binaries: sense or sensibility, emotion or restraint, Willoughby or Colonel Brandon, Elinor or Marianne. I’d relied so much on my earlier ways of reading over the years that I’d never noticed that this book begins with the death of a parent and the loss of a home. I also saw for the first time that this is a novel about grief and heartbreak and about finding one’s path through life’s difficult parts. It’s not Sense vs Sensibility or Marianne vs Elinor. It’s Sense and Sensibility. It is Marianne and Elinor.

After listening to the audio book, I flipped through the notations in my original copy. I was surprised to see that my younger self had underlined a passage that brought me to a halt on my walk: “’Dear, dear Norland!’ said Marianne as she wandered alone on the last evening of being there. . . . And you, ye well-known trees!—but you will continue the same.—No leaf will decay because we are removed . . . you will continue the same: unconscious of the pleasure or the regret you occasion, and insensible of any change in those who walk under your shade” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). A younger me had written “trees” in the margin beside this underlined passage—maybe for a paper. But this version of me was stopped in my tracks by this passage because I couldn’t see the path for the tears in my eyes. I know that when we do finally sell our family house, I will stand in our backyard one last time and stare up at the towering elm trees that were saplings when I was born. They grew as I did and I used to climb and read under them all summer. I know I will remember this passage from my favourite novel and that I will cry. But I will also carry on. I will be both Marianne and Elinor, sense and sensibility.

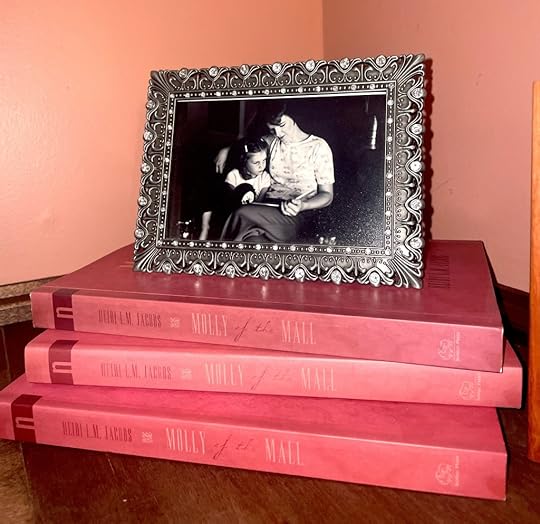

In Molly of the Mall, I wrote about how the ten-year-old Molly reads the publisher’s motto in her copy of Emma as a directive: “Everyman, I will go with thee, and be thy guide, / In thy most need to go by thy side.” When I wrote that, I ascribed those emotions to a fictional character. I have long known that the Christmas gift certificate got me the book that would go with me and be my guide for my lifetime. What I did not know until this week is that Sense and Sensibility would also be the novel that in my most need, would go by my side.

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Tony Tanner (1969, 1986). All photos by Heidi.

Heidi LM Jacobs is a librarian at the University of Windsor and the author of three books including the Leacock award winning Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass and Purveyor of Fine Footwear (NeWest Press, 2019).

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility,” is by Deborah Yaffe.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.