Voynich Reconsidered: Arabic revisited

In a previous article on this platform, I started to explore this concept of Arabic as a possible precursor language to the text of the Voynich manuscript.

Arabic is an abjad language, in which the long vowels are written and the short vowels are either omitted, or represented by diacritics known as hamza. If hamza are used, they are placed above or below the preceding consonant, or above or below an initial vowel alef (ا), or both. If a hamza is linked with an alef, it changes the sound of the vowel: for example, alef kasra (إ) is pronounced somewhat like the English short “u”, as in “put”. However, in many medieval Arabic texts, the hamza are omitted, leaving the reader to understand or to pronounce the words by reference to the context.

In order to assess Arabic as a precursor language, I had to make a number of assumptions. Some of my assumptions were common to my analysis of other languages, for example:

My assumptions that were specific to the Arabic language included the following:

I therefore assumed that the scribes could distinguish the initial, medial and final forms of Arabic letters; and crucially, that they did not carry over these distinctions to the Voynich glyphs. For example, they would map an initial or medial kaf (ک) and a final kaf (ك) to the same glyph.

Right to left?

One consideration remained unresolved. Arabic is written from right to left. The Voynich text has every appearance of having been written from left to right. The questions arose: did the Voynich scribes reverse the order of the Arabic words? Or did they reverse the order of the letters within the words? Or both? To my mind, it did not seem possible to make an a priori judgement. I felt that if I attempted some mappings, and if some of these mappings yielded recognisable Arabic words in some order, or strings that could be reversed to make recognisable Arabic words, only then it might be possible to fathom what the scribes had done.

Letter and glyph frequencies

As with other languages that I have investigated, I started by examining the frequencies of Arabic letters as written in the fifteenth century, or the preceding centuries. I found a number of relevant corpora, including the following:

For the Voynich manuscript, I took Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration as a starting point. As I have reported in other articles on this platform, I have developed a series of alternative transliterations based on v101. Most of my alternative transliterations make a single change with reference to a group of related v101 glyphs; for example, my v130 transliteration merges the v101 glyphs {6}, {7} and {&} with the glyph {8). Currently, the alternative transliterations are numbered from v101④ to v226.

For any given precursor language to be tested, I have developed two metrics by which to prioritise the alternative transliterations. One is the correlation coefficient between letter frequencies in the precursor language and glyph frequencies in the Voynich transliteration (expressed by the RSQ function in Excel). The other is the average absolute difference between letter frequencies and equally-ranked glyph frequencies. In any case, my usual procedure is to test all of the transliterations.

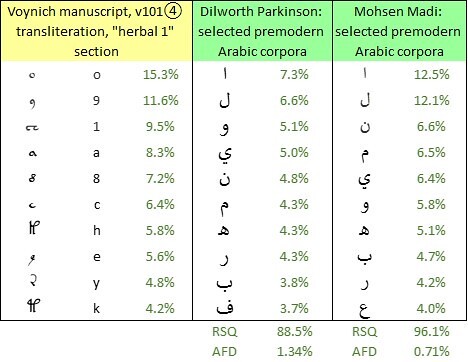

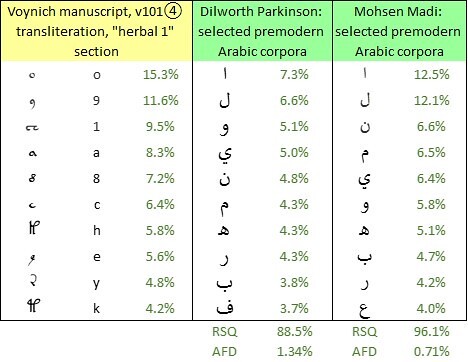

The frequencies of the ten most common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration, "herbal" section, and the ten most common letters in Dr Dilworth Parkinson’s corpora of 8th to 15th century Arabic, and Mohsen Madi’s corpus of (mainly) fourteenth-century Arabic. Author's analysis.

Mappings

The next step was to explore the potential of these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings. For example, the most frequent Voynich glyph {o} could plausibly map to and from the most frequent Arabic letter, alef (ا).

As I proposed in another article on this platform, to my mind an efficient test of such mappings is to try the “word” {8am}, which is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. If (8am} maps to a recognisable word, we may be encouraged to try the same mapping with other Voynich “words”.

Again, I have kept in mind that, if the precursor documents were in Arabic, we do not know whether the Voynich scribes reversed the order of the words, or of the letters within words. Therefore, it seemed to me that if a mapping did not yield a common Arabic word, we could try reversing the order of the Arabic letters and see whether that yielded a more common word.

For each of my alternative transliterations, I mapped {8am} to a string of Arabic letters, using frequency comparisons based on both Dr Parkinson’s three corpora and Mohsen Madi’s (mainly) fourteenth-century corpus. To test whether the resulting text strings were real Arabic words, I took word counts from the full range of Dr Parkinson’s premodern corpora, including the Holy Quran, the Hadith and the Adab literature.

With Dr Parkinson’s corpora, the mappings yielded a few recognisable Arabic words, none of them common, including the following:

Next steps

The mapping of {8am} to منع was an outcome of three alternative transliterations - v221, v223 and v225 – all of which make a distinction between the glyph {9} in the final position of a Voynich “word”, and the {9} in any other position. The v225 transliteration also distinguishes the initial {o} from the medial, final and isolated {o}. These distinctions have the effect of reducing the extremely high frequencies of {9} and {o} in the conventional transliterations, and thereby making the Voynich manuscript more statistically similar to a natural language.

The logical next step would be to try mappings of other common Voynich “words”, such as {oe} and {1c9}, to text strings in medieval Arabic.

Arabic is an abjad language, in which the long vowels are written and the short vowels are either omitted, or represented by diacritics known as hamza. If hamza are used, they are placed above or below the preceding consonant, or above or below an initial vowel alef (ا), or both. If a hamza is linked with an alef, it changes the sound of the vowel: for example, alef kasra (إ) is pronounced somewhat like the English short “u”, as in “put”. However, in many medieval Arabic texts, the hamza are omitted, leaving the reader to understand or to pronounce the words by reference to the context.

In order to assess Arabic as a precursor language, I had to make a number of assumptions. Some of my assumptions were common to my analysis of other languages, for example:

• that the Voynich producer provided the scribes with source documents in the precursor languages, and that these documents were approximately contemporary with the production of the manuscriptReasonable persons may of course disagree; but to my mind these instructions would be sufficiently simple to enable the producer to commission the work and to trust the scribes to proceed with minimal supervision.

• that the producer gave the scribes instructions as to how to map those documents to the symbols that we now know as the Voynich glyphs

• that the instructions were based on letters (rather than, say, words, parts of speech, sounds, or other aspects of the source documents)

• that the instructions specified a mapping of each source letter (objectively defined) uniquely to a corresponding glyph.

My assumptions that were specific to the Arabic language included the following:

• that the scribes knew the Arabic script (indeed, it would be logical to assume that the producer hired them for this knowledge)I made one additional, and major, assumption. Written Arabic is mainly cursive: that is, most letters are joined to the preceding and following letters. Therefore, most letters have initial, medial and final forms. For example, the initial and medial kaf are written (ک); the final kaf is written (ك). However, the Voynich text does not appear to be cursive; to my mind, the glyphs are separated by distinct gaps. (Here I will restate my belief that the symbol represented in the v101 transliteration by the two-glyph string {4o} is a single glyph.)

• that they knew the functions of the hamza, and could pronounce a word and understand its meaning even if the hamza were not present

• that in the absence of a hamza, if necessary to preserve meaning, they could add the appropriate hamza and map it in some objective way to the Voynich glyphs.

I therefore assumed that the scribes could distinguish the initial, medial and final forms of Arabic letters; and crucially, that they did not carry over these distinctions to the Voynich glyphs. For example, they would map an initial or medial kaf (ک) and a final kaf (ك) to the same glyph.

Right to left?

One consideration remained unresolved. Arabic is written from right to left. The Voynich text has every appearance of having been written from left to right. The questions arose: did the Voynich scribes reverse the order of the Arabic words? Or did they reverse the order of the letters within the words? Or both? To my mind, it did not seem possible to make an a priori judgement. I felt that if I attempted some mappings, and if some of these mappings yielded recognisable Arabic words in some order, or strings that could be reversed to make recognisable Arabic words, only then it might be possible to fathom what the scribes had done.

Letter and glyph frequencies

As with other languages that I have investigated, I started by examining the frequencies of Arabic letters as written in the fifteenth century, or the preceding centuries. I found a number of relevant corpora, including the following:

• by courtesy of Mohsen Madi: a compilation of three major works:A priori, I saw no compelling reason to select one corpus over another; it seemed advisable to try all of them, and to see where that led.

* The Beginning and the End, Volumes 1-7, by Abulfida' ibn Kathir (1300-1373), containing 4,326,031 letters;

* The Sealed Nectar, a compilation of the Prophet’s sayings (therefore dating to the 7th century) by Safiur Rahman Mubarakpuri, containing 553,740 letters;

* The Masterpiece of the Brides by Al-shuri, containing 242,361 letters in old Arabic

• by courtesy of Dr Dilworth Parkinson of Brigham Young University:

* the Grammarians corpus, dating from the 8th through 13th centuries, with 2,537,462 letters;

* the Medieval Philosophy and Science corpus, dating from the 9th through 15th centuries, with 4,554,954 letters;

* the Thousand and One Nights, first referenced in Arabic in the 12th century, with 2,326,696 letters.

For the Voynich manuscript, I took Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration as a starting point. As I have reported in other articles on this platform, I have developed a series of alternative transliterations based on v101. Most of my alternative transliterations make a single change with reference to a group of related v101 glyphs; for example, my v130 transliteration merges the v101 glyphs {6}, {7} and {&} with the glyph {8). Currently, the alternative transliterations are numbered from v101④ to v226.

For any given precursor language to be tested, I have developed two metrics by which to prioritise the alternative transliterations. One is the correlation coefficient between letter frequencies in the precursor language and glyph frequencies in the Voynich transliteration (expressed by the RSQ function in Excel). The other is the average absolute difference between letter frequencies and equally-ranked glyph frequencies. In any case, my usual procedure is to test all of the transliterations.

The frequencies of the ten most common glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v101④ transliteration, "herbal" section, and the ten most common letters in Dr Dilworth Parkinson’s corpora of 8th to 15th century Arabic, and Mohsen Madi’s corpus of (mainly) fourteenth-century Arabic. Author's analysis.

Mappings

The next step was to explore the potential of these juxtapositions as correspondences or mappings. For example, the most frequent Voynich glyph {o} could plausibly map to and from the most frequent Arabic letter, alef (ا).

As I proposed in another article on this platform, to my mind an efficient test of such mappings is to try the “word” {8am}, which is the most common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. If (8am} maps to a recognisable word, we may be encouraged to try the same mapping with other Voynich “words”.

Again, I have kept in mind that, if the precursor documents were in Arabic, we do not know whether the Voynich scribes reversed the order of the words, or of the letters within words. Therefore, it seemed to me that if a mapping did not yield a common Arabic word, we could try reversing the order of the Arabic letters and see whether that yielded a more common word.

For each of my alternative transliterations, I mapped {8am} to a string of Arabic letters, using frequency comparisons based on both Dr Parkinson’s three corpora and Mohsen Madi’s (mainly) fourteenth-century corpus. To test whether the resulting text strings were real Arabic words, I took word counts from the full range of Dr Parkinson’s premodern corpora, including the Holy Quran, the Hadith and the Adab literature.

With Dr Parkinson’s corpora, the mappings yielded a few recognisable Arabic words, none of them common, including the following:

نيت - word count: 486 - Neet (name of queen)With Mohsen Madi’s corpus, I found mappings to several recognisable, and considerably more frequent, Arabic words, of which the following topped the lists:

منت - word count: 288 - English: she afflicted

ينت - word count: 184 - English: he/it swayed.

منع - word count: 5,277 - English: prevention/preventsFrom these results, I was inclined to think firstly that, if medieval Arabic was a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript, it was better represented by fourteenth-century corpora than by earlier texts. Secondly, the most satisfactory mapping of the “word” {8am} was منع (as a noun, “prevention”, or as a verb, “he, she or it prevents”); this required the Voynich scribes to write the first (rightmost) Arabic letter first (that is, leftmost in the Voynich text).

يمٲ - reversed: أمي - word count: 4,130 - English: my mother/maternal

ميٲ - reversed: أيم - word count: 3,914 - English: widow/widowed.

Next steps

The mapping of {8am} to منع was an outcome of three alternative transliterations - v221, v223 and v225 – all of which make a distinction between the glyph {9} in the final position of a Voynich “word”, and the {9} in any other position. The v225 transliteration also distinguishes the initial {o} from the medial, final and isolated {o}. These distinctions have the effect of reducing the extremely high frequencies of {9} and {o} in the conventional transliterations, and thereby making the Voynich manuscript more statistically similar to a natural language.

The logical next step would be to try mappings of other common Voynich “words”, such as {oe} and {1c9}, to text strings in medieval Arabic.

Published on June 27, 2024 13:18

•

Tags:

arabic, dilworth-parkinson, ibn-kathir, mohsen-madi, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 67 followers