Isabelle de Montolieu’s Sense and Sensibility, by Peter Sabor

Who was Isabelle de Montolieu, and why is she important to lovers of Sense and Sensibility? Born Jeanne-Isabelle-Pauline Polier de Bottens in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1751, she was twenty-four years Jane Austen’s senior.

(From Sarah: This is the tenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

This pastel portrait of about 1770 shows Isabelle de Montolieu as a young woman, shortly after her short-lived marriage to Benjamin de Crousaz, who died in 1775.

She made her reputation with Caroline de Lichtfield, ou Mémoires d’une famille prussienne, published in both Paris and London in 1786, and at once freely translated by the radical writer Thomas Holcroft as Caroline of Lichtfield. A Novel; both the French and English versions would go through many subsequent editions. In the same year, she married her second husband, the baron Louis de Montolieu. After his death in 1800, she remained a widow for over three decades, dying in Vennes, near Lausanne, in 1832 at the age of 81.

The Musée Historique Lausanne holds several portraits of her in her later years. The one here by Jacques Louis Samuel Piot was painted at the beginning of her second widowhood, when she was establishing herself as an author. Holding an opened book in one hand and a manuscript in the other, she is depicted as a woman writer at work. Her quill pen, resting in an inkwell, is ready to be used; behind the inkwell are two substantial volumes, presumably one of her own publications.

De Montolieu produced little during either of her marriages (we might speculate whether Austen would have published her novels had she accepted Harris Bigg-Wither’s proposal in December 1802), but during the last thirty years of her life she was astonishingly prolific as both an original writer and a translator of works from German and English into French.

Among her translations was the first French version of Sense and Sensibility: Raison et sensibilité, ou les deux manières d’aimer (Sense and sensibility, or the two ways of loving), issued in four volumes by the Parisian publisher Claude Arthus-Bertrand in 1815. 1,000 copies were published: almost certainly a larger print run than that for the first edition of Sense and Sensibility.

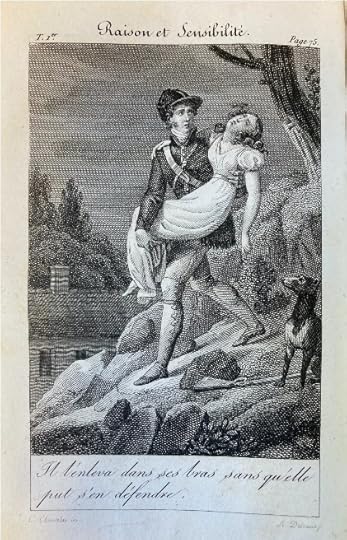

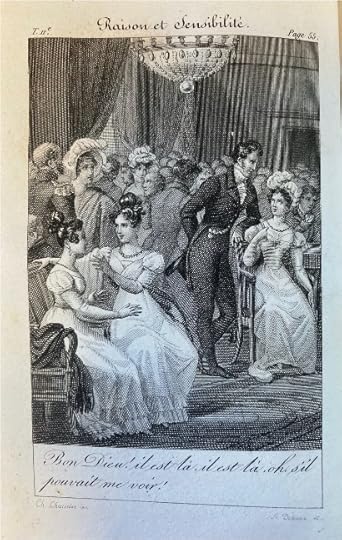

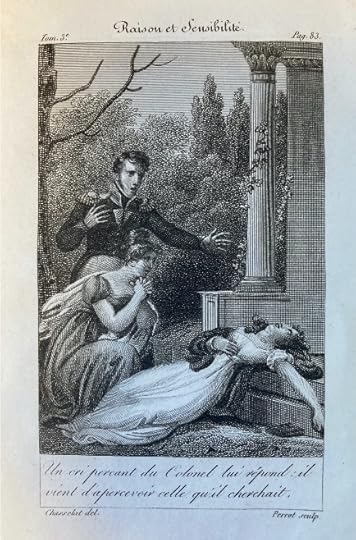

And as a further sign of the marketability of de Montolieu’s translation, in December 1827 Arthus-Bertrand published a three-volume second edition, equipped with frontispiece engravings for each volume. These engravings, designed by Charles-Abraham Chasselat and engraved by Auguste Delvaux (for volumes one and two) and Jean-Simon-Narcisse Perrot (for volume three), would have entailed a major expenditure by Arthus-Bertrand, who was evidently confident that a considerable number of readers would purchase the work. No such investment in Austen during her lifetime was shown by either of her English publishers, Thomas Egerton or John Murray, and no illustrated edition of any Austen novel in English would appear until Richard Bentley’s “standard novels” set of 1832-33.

De Montolieu’s esteem for both Austen’s novel and her own translation, expressed in a letter of 20 September 1815 to Arthus-Bertrand, is striking: “I have become attached to this work to which I have given the utmost care, and which is really very fine, and which I believe will be read with pleasure, despite the difficulty of these times” (David Gilson, A Bibliography of Jane Austen [Clarendon Press, 1985], 154). But the “care” given to Sense and Sensibility by its first translator included some substantial rewriting. For de Montolieu and her contemporaries, fidelity to the original was of little concern; instead, publishers and their chosen translators wished to turn English novels into something amenable to the taste of the French reading public. Both abridgement and expansion were commonplace. Plots were altered, often in the interest of changing the open endings favoured by Austen into something more conclusive and reassuring; French translators seem to have regarded the dull elves mocked by Austen as their principal readership. Satire and irony were generally eschewed; sentimentality and sensibility, in contrast, were highly prized. New subtitles were added (“two ways of loving”) and characters’ names were changed at will; thus Marianne and Margaret Dashwood become Maria and Emma. And the relative significance of characters can be increased or decreased. De Montolieu, for instance, had a particular fascination with Willoughby and gives him a larger role in Raison et sensibilité than the one he plays in Austen’s novel.

As an example of de Montolieu’s recasting of Sense and Sensibility, consider what she does to the unpromising Margaret Dashwood, who, Austen tells us, “was a good-humoured well-disposed girl; but as she had already imbibed a good deal of Marianne’s romance without having much of her sense, she did not, at thirteen, bid fair to equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). In de Montolieu’s version, the references to Marianne’s sense and to Margaret’s shortcomings are both removed, Margaret’s name is changed, and a year is taken off her age: “Her younger sister, the young Emma, was still only a child; but at twelve years old she already promised, in a few years time, to be as beautiful and likeable as her sisters” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). Austen’s irony and satirical touches have disappeared, and Margaret/Emma is duly established as a worthy counterpart for her two admirable sisters.

Equally striking is de Montolieu’s determination to put Marianne and Willoughby at the forefront of Raison et sensibilité, while making Elinor of no more than secondary interest and Edward of little interest at all. This is shown graphically by the three engravings chosen to illustrate the second edition of her translation.

The first depicts Marianne, with her twisted foot, in the arms of Willoughby. In Austen’s account: “The gentleman offered his services, and perceiving that her modesty declined what her situation rendered necessary, took her up in his arms without farther delay, and carried her down the hill” (Volume 1, Chapter 9). In de Montolieu’s version, the phrase “without further delay” is replaced by “sans qu’elle pût s’en défendre” (without her being able to defend herself) (Volume 1, Chapter 9), and the illustration follows suit, furnishing these words in the caption and showing Marianne in a fetching swoon: nothing so prosaic as a foot injury here.

The second illustration also makes Willoughby the dominant figure. In Sense and Sensibility, Austen gives us Marianne’s words at a fashionable party in London, when she suddenly perceives her absent suitor: “‘Good heavens!’ she exclaimed, ‘he is there—he is there—Oh! why does he not look at me? why cannot I speak to him?’” (Volume 2, Chapter 6). In the engraving, a strikingly tall and centrally placed Willoughby towers over the other figures while Elinor is placating a highly agitated Marianne, seated at the edge of the composition.

Having swooned in the first illustration and had a nervous fit in the second, Marianne has fallen into a dead faint in the third, where she is posed on the steps of a conveniently located neo-Greek temple. Elinor, looking suitably alarmed and helpless, is crouching ineffectually by her side, while a surprisingly youthful and dashing Colonel Brandon expresses his alarm in a much more dramatic manner. The scene is one of de Montolieu’s fabrications: Marianne has fainted in horror on seeing the Colonel with an attractive young woman, Madame Summers, who we subsequently discover is in fact the Eliza seduced by Willoughby (renamed Caroline here). The illustration epitomizes de Montolieu’s aims in recasting Austen’s novel. Her Colonel Brandon is a far more imposing figure than his flannel-waistcoated precursor; Elinor is a shadow of Austen’s astute and sensitive heroine; Marianne’s sensibility has been taken to a parodic extreme, akin to that of the figures populating Austen’s juvenilia; Edward, of whom de Montolieu seems to have despaired, is out of the picture; and behind everything is Willoughby, the driving force of Raison et sensibilité. He will, in de Montolieu’s version, marry Eliza/Caroline a year after the death of his wife, who had been killed after falling from her phaeton.

De Montolieu was well aware of Austen’s artistry but knew that it was alien to the taste of her readership. She devoted her utmost care to Raison et sensibilité, as she claimed. By rewriting, as well as translating, Austen’s novel, she gave her intended audience what they wanted: a version of Sense and Sensibility made palatable for French readers.

Quotations are from the Cambridge Edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Edward Copeland (2006), and from the first edition of Raison et sensibilité, ou les deux manières d’aimer (Paris: Arthus-Bertrand, 1815). Translations from the French are my own. A longer, more detailed version of this post, “Less Sense, More Sensibility: Isabelle de Montolieu’s Raison et Sensibilité,” appears in Persuasions 44 (2022), 158-70. This version appears with permission of the editor. The flower photos were taken in Quebec City by Marie Legroulx.

Peter Sabor, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, is Distinguished James McGill Professor of English at McGill University, Montreal, where he is also Director of the Burney Centre. His publications on Jane Austen include an edition of her early writings, Juvenilia (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Manuscript Works, co-edited with Linda Bree and Janet Todd (Broadview, 2013); and The Cambridge Companion to Emma (Cambridge University Press, 2015). He is also the Principal Investigator for Reading with Austen, a digital recreation of Godmersham Park Library: www.readingwithausten.com.

I took this photo of Peter (on the right) and Patrick Stokes (great-great-grandson of Jane Austen’s brother Charles Austen) at the 2017 Jane Austen Society conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Prodigal Sons in Sense and Sensibility,” is by Joyce Kerr Tarpley.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Landscapes of the Mind and Map in Sense and Sensibility, by Hazel Jones

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.