Voynich Reconsidered: doubled letters

In Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript, there are very few glyphs that are repeated, in the sense that, for example, the letter e is repeated in the English word "see".

The only frequent instance is {cc}, which occurs 1,686 times; after that, {oo} occurs just 55 times.

There are a few glyphs that visually resemble doubles of other glyphs, notably {C} which resembles {cc}; but Claston chose to give them separate keys. There are several common glyphs, especially {m} and {n}, that could be interpreted as having an embedded double {i}. And there are some common glyphs, notably {1}, {h} and {k}, which have a bifurcate structure and look like they might represent doubled letters or bigrams in the presumed precursor languages.

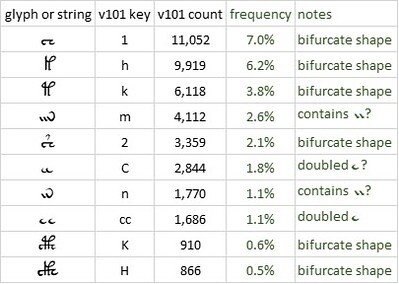

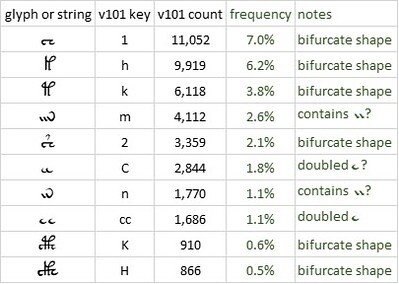

Below is a selection of common glyphs which look as if they might represent or contain doubled glyphs, together with the {cc} string.

This is a subjective selection of glyphs which have the visual appearance of representing or containing doubled glyphs or bigrams. Author's analysis, based on v101 transliteration. Frequency is calculated as count of glyph or string in v101, divided by total glyph count in v101. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjLwVA

Much of my research on the Voynich manuscript has been based on the following working assumptions:

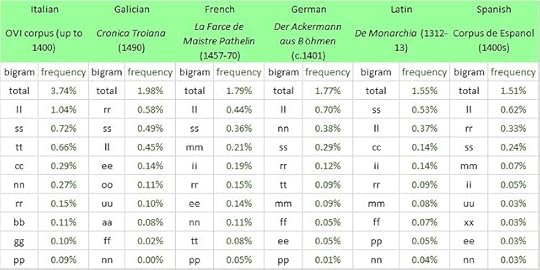

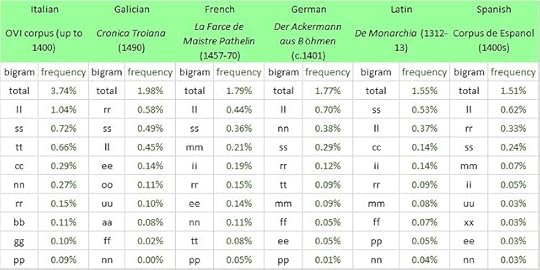

Most European natural languages have some doubled letters. I calculated the frequencies of doubled letters in several medieval European languages, with the results shown in the table below. In these languages, there was no doubled letter whose frequency was more than 1.04 per cent of the total letter count.

The frequencies of the most common doubled letters in selected medieval European languages. Frequencies are calculated as counts of bigrams, divided by total counts of letters in the respective corpora. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjL4yF

If we stick with the assumption that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping from the precursor documents, it seems a necessary inference that glyphs such as {1}, {h}, {k} and {m} cannot represent or contain representations of doubled letters. These glyphs are simply too frequent.

To my mind, the Voynich producer might have instructed at least two possible treatments of doubled letters:

Could doubled letters be distinguished?

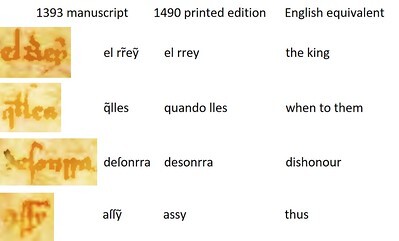

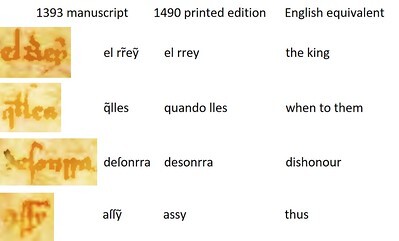

In passing we might observe that if the Voynich scribes were working from manuscripts in the precursor languages, the doubled letters might not have been readily distinguishable from single letters. Below are some examples from the 1373 manuscript of Cronica Troiana. I conjecture that the Voynich scribes were working men who were paid by the page, and that the Voynich producer did not instruct or encourage them to make editorial or creative decisions. Faced with a symbol that might or might not be a doubled letter, I conjecture that the scribes might have used a different glyph from that for a clearly defined single letter.

Some examples of doubled letters in the 1373 manuscript of Crónica Troiana by Fernán Martis; with their representations in the printed edition of 1490, and their equivalents in modern English. Author's analysis.

Re-ordering glyphs within “words”

The above tests would make sense if the glyphs in the Voynich “words” followed the same order as the letters in the precursor words. However, as I have observed in several articles on this platform, it is conceivable that they do not. Mary D'Imperio's concept of "the five states", and Massimiliano Zattera's identification of a "slot alphabet", permit us to imagine that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes, after mapping from letters to glyphs, to re-order the glyphs in each “word”.

We can see how this might work by re-ordering a hypothetical source document. Let us say that the document is the manuscript of Cronica Troiana in Galician, published by Fernan Martis in 1373. The first line reads:

This example should demonstrate that some form of re-ordering, whether based on an existing alphabet or on some system invented by the Voynich producer, will create doubled and tripled glyphs where doubled letters were not originally present. To take a simple example: the Voynich “word” {8am}, which appears to have three glyphs, could be interpreted as a five-glyph “word”, namely {8aiiN]. This “word” in turn could be a re-ordering of a prior ”word”, for example {i8aNi} or {iNa8i}, which retained the order of the precursor letters.

To test this hypothesis, again we would need to create variants of our source corpora. For example, with various online tools we can easily reproduce a variant of the full text of Cronica Troiana in which the letters of each word follow the order of the Latin alphabet. On its own, this process will not change the letter frequencies, and therefore will not change the reverse-engineered mapping from letters to glyphs. However, we could then apply one of the treatments that we imagined on the part of the Voynich scribes, namely:

In either case, the letter frequencies would change; therefore the ranking of letters by frequency would change; and therefore the mappings between glyphs and letters would change. We could then map some common Voynich “words”, such as {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}, to Galician. In comparison with our earlier mappings, this might yield more real words, and better still, more common real words, in Galician. If so, we might suspect that we were onto something. Again, I will investigate tests of this nature, and post on this platform.

Few doubled letters?

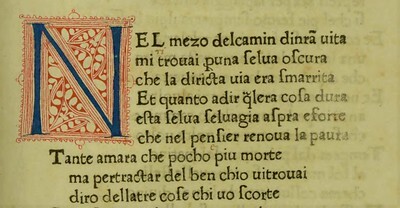

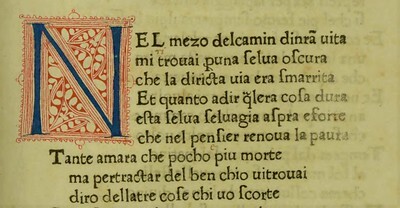

There remains the possibility that the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from documents in languages which had few doubled letters. Italian, as represented by the 1472 edition of La Divina Commedia would fit for this description.

The first nine lines of the first printed edition of La Divina Commedia (dated 1472), which contain just two instances of doubled letters: "smarrita" and "dellatre".

The only frequent instance is {cc}, which occurs 1,686 times; after that, {oo} occurs just 55 times.

There are a few glyphs that visually resemble doubles of other glyphs, notably {C} which resembles {cc}; but Claston chose to give them separate keys. There are several common glyphs, especially {m} and {n}, that could be interpreted as having an embedded double {i}. And there are some common glyphs, notably {1}, {h} and {k}, which have a bifurcate structure and look like they might represent doubled letters or bigrams in the presumed precursor languages.

Below is a selection of common glyphs which look as if they might represent or contain doubled glyphs, together with the {cc} string.

This is a subjective selection of glyphs which have the visual appearance of representing or containing doubled glyphs or bigrams. Author's analysis, based on v101 transliteration. Frequency is calculated as count of glyph or string in v101, divided by total glyph count in v101. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjLwVA

Much of my research on the Voynich manuscript has been based on the following working assumptions:

• that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes to made a one-to-one transcription from documents in natural languages,Since evidence exists that Voynich purchased the manuscript in Frascati, Italy, I chose to prioritise the medieval languages used within some delimited geographical radius of Italy: for example, French, Italian or Latin.

• and that those languages were more likely to be European than not.

Most European natural languages have some doubled letters. I calculated the frequencies of doubled letters in several medieval European languages, with the results shown in the table below. In these languages, there was no doubled letter whose frequency was more than 1.04 per cent of the total letter count.

The frequencies of the most common doubled letters in selected medieval European languages. Frequencies are calculated as counts of bigrams, divided by total counts of letters in the respective corpora. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2qjL4yF

If we stick with the assumption that the Voynich scribes used a one-to-one mapping from the precursor documents, it seems a necessary inference that glyphs such as {1}, {h}, {k} and {m} cannot represent or contain representations of doubled letters. These glyphs are simply too frequent.

To my mind, the Voynich producer might have instructed at least two possible treatments of doubled letters:

• to ignore them: that is, to treat any doubled letter as a single letterTo test these hypotheses, it would be necessary to take each source corpus and create two variants, reflecting the above processes respectively; to recalculate the letter frequencies; and to try some mappings of selected Voynich “words” to the language in question. I will explore these tests and post the results on this platform.

• to treat them as distinct from their single counterparts: that is; to assign one glyph to the single letter and another to the doubled letter.

Could doubled letters be distinguished?

In passing we might observe that if the Voynich scribes were working from manuscripts in the precursor languages, the doubled letters might not have been readily distinguishable from single letters. Below are some examples from the 1373 manuscript of Cronica Troiana. I conjecture that the Voynich scribes were working men who were paid by the page, and that the Voynich producer did not instruct or encourage them to make editorial or creative decisions. Faced with a symbol that might or might not be a doubled letter, I conjecture that the scribes might have used a different glyph from that for a clearly defined single letter.

Some examples of doubled letters in the 1373 manuscript of Crónica Troiana by Fernán Martis; with their representations in the printed edition of 1490, and their equivalents in modern English. Author's analysis.

Re-ordering glyphs within “words”

The above tests would make sense if the glyphs in the Voynich “words” followed the same order as the letters in the precursor words. However, as I have observed in several articles on this platform, it is conceivable that they do not. Mary D'Imperio's concept of "the five states", and Massimiliano Zattera's identification of a "slot alphabet", permit us to imagine that the Voynich producer instructed the scribes, after mapping from letters to glyphs, to re-order the glyphs in each “word”.

We can see how this might work by re-ordering a hypothetical source document. Let us say that the document is the manuscript of Cronica Troiana in Galician, published by Fernan Martis in 1373. The first line reads:

“Agora diz oconto q̃ os gregos oūūerō grā peſar q̃ndolles ercoɫs + jāāſon contarō agrā”which contains three instances of doubled letters: “ūū”, “ll” and “āā”. Suppose that we re-order the letters in each word, on the basis of the Latin alphabet. The result is:

“aAgor diz cnooot q̃ os eggros eoōrūū grā aeprſ dellnoq̃s ceɫors + āājnoſ acnoōrt aāgr”Now there are at least seven and potentially ten instances of doubled letters, depending on whether we treat accented letters as different from unaccented letters, and upper case as different from lower case.

This example should demonstrate that some form of re-ordering, whether based on an existing alphabet or on some system invented by the Voynich producer, will create doubled and tripled glyphs where doubled letters were not originally present. To take a simple example: the Voynich “word” {8am}, which appears to have three glyphs, could be interpreted as a five-glyph “word”, namely {8aiiN]. This “word” in turn could be a re-ordering of a prior ”word”, for example {i8aNi} or {iNa8i}, which retained the order of the precursor letters.

To test this hypothesis, again we would need to create variants of our source corpora. For example, with various online tools we can easily reproduce a variant of the full text of Cronica Troiana in which the letters of each word follow the order of the Latin alphabet. On its own, this process will not change the letter frequencies, and therefore will not change the reverse-engineered mapping from letters to glyphs. However, we could then apply one of the treatments that we imagined on the part of the Voynich scribes, namely:

• replace each doubled or tripled letter with a single letter; so that, for example “cnooot” becomes “cnot”These kinds of treatment might help to address both the rarity of doubled glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, and also the relatively low average length of the Voynich “words”, in comparison with words in most natural languages.

• replace each doubled letter with a unique but different Unicode symbol: so that for example, “cnooot” becomes “cnoôt” or “cnôot”.

In either case, the letter frequencies would change; therefore the ranking of letters by frequency would change; and therefore the mappings between glyphs and letters would change. We could then map some common Voynich “words”, such as {8am}, {1oe} and {2c9}, to Galician. In comparison with our earlier mappings, this might yield more real words, and better still, more common real words, in Galician. If so, we might suspect that we were onto something. Again, I will investigate tests of this nature, and post on this platform.

Few doubled letters?

There remains the possibility that the Voynich manuscript was transcribed from documents in languages which had few doubled letters. Italian, as represented by the 1472 edition of La Divina Commedia would fit for this description.

The first nine lines of the first printed edition of La Divina Commedia (dated 1472), which contain just two instances of doubled letters: "smarrita" and "dellatre".

Published on September 30, 2024 12:48

•

Tags:

cronica-troiana, divina-commedia, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 67 followers