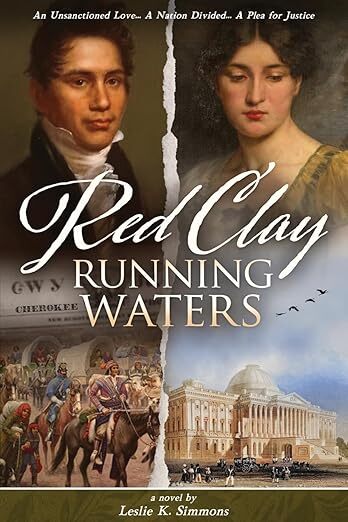

Sunday Review: Red Clay, Running Waters by Leslie K. Simmons

Many of us know at least a minimal amount about the tragic Trail of Tears, in which the U.S. government forced the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) to leave their ancestral lands and move to the Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma) west of the Mississippi River. Thousands died during the journey.

What is less known are the events that led up to this calamitous outcome. In her biographical novel Red Clay, Running Waters, Leslie K. Simmons provides an in-depth look at how the Cherokee fought to retain their homeland by focusing the story on one important figure: Skaleeloskee, known to history as John Ridge. The son of a Cherokee leader, John was sent from his home to a mission school in Connecticut at the age of 16. He excelled at his studies and became an accomplished orator. He also fell in love with Sarah Bird Northrup, the white daughter of the school’s steward.

In the 1820s, a relationship between a native man and white woman was controversial, and the young couple’s desire to marry creates a firestorm of opposition. However, the two had formed a deep bond, forged in part because of their attraction to each other but more importantly because of shared ideals. Simmons excels at portraying their love, both in the beginning infatuation stage and over the course of time. After persisting for two years, John and Sarah finally were allowed to marry in 1824. The prejudice and discrimination they faced because of their relationship was merely a foretaste of what was to come.

Sarah traveled with John to Georgia to live in the Cherokee Nation, which stretched across parts of Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. The Cherokee were in the process of developing a constitutional government similar to that of the United States. John became a member of the National Council. However, because of Americans’ lust for good farmland and the 1828 discovery of gold in Georgia, the United States began to pressure the Cherokee to cede their homeland and move.

One mistake whites often make when thinking of native peoples is assuming that they are somehow monolithic in their thinking and in their attitudes toward whites. As I learned while writing my own novel Blood Moon: A Captive’s Tale, that is often not the case. Factions existed among the Cherokee with strongly held, opposing opinions about how to deal with the U.S. government’s demands. John, supported by Sarah, fought hard for what he thought would be the best solution, but equally passionate leaders argued for other outcomes.

Simmons portrays the conflict in detail in her novel. The arguments were complex, and some of the people involved were inconsistent and at times devious. Although highly educated and skilled at both writing and speaking, John wasn’t always trusted by more traditional Cherokee who viewed him as “too white.” The situation in the novel vividly shows the dilemma often faced by native peoples: do they adopt white ways to gain tools to help fight for their people, or is the cost too high in the loss of their culture and perhaps legitimacy in the eyes of their people?

This novel will be especially appreciated by readers who enjoy policy debates and situations with multiple shades of grey rather than a clear blank-and-white outcome.