“Amazing Grace” Didn’t Stand out as “Amazing” When First Published

-This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a public affairs specialist in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the July-August edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

There’s a famous bit of country music lore that says Dolly Parton wrote two of her biggest hits, “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You,” on the same night.

The story may not be perfectly true (Parton has said she might have written the songs a few days apart, though they were first recorded on the same cassette), but it’s stuck around in pop culture mythology for years. There’s something almost mystical about the idea that two such celebrated works could share a single point of origin. The stars don’t often align so perfectly. But rare is a Library specialty.

Centuries ago, in the village of Olney, England, the Rev. John Newton and poet William Cowper produced two iconic cultural artifacts for a single collection, the “Olney Hymns” of 1779.

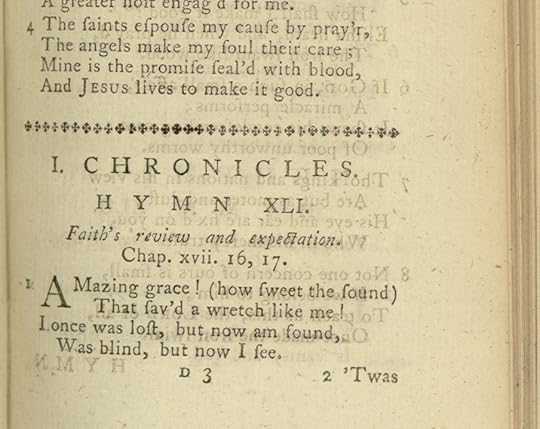

The hymnal’s best-known work, the beloved “Amazing Grace,” is one of the most-recorded songs in history. It didn’t particularly stand out at the time of publication, though — it’s not called “Amazing Grace,” just numbered “Hymn 41” and begins at the bottom of page 53 (in viewing the Library’s digital version, this is image 94). The hymnbook was huge, running to three volumes and more than 450 pages, containing 280 hymns by Newton and 68 by Cowper.

Newton wrote in the preface that the pieces should be simple, for the common folk, and not strain to the reach the heights of poetry. “They should be hymns, not odes, if designed for public worship and for the use of plain people,” he wrote. “Perspicuity, simplicity and ease, should be chiefly attended to; and the imagery and coloring of poetry, if admitted at all, should indulged very sparingly and with great judgment.”

In the book’s layout, “Grace” is the first entry in a group of songs listed under the biblical book of I Chronicles. Under “Hymn 41,” a subheading says that the hymn relates to Chapter 17, verses 16 and 17, and is about “Faith’s review and expectation.”

“Amazing Grace” was just called “Hymn XLI,” when first published in “Olney Hymns.” XLI is the Roman numeral for 41. Music Division.

“Amazing Grace” was just called “Hymn XLI,” when first published in “Olney Hymns.” XLI is the Roman numeral for 41. Music Division.Newton, once a self-described infidel and libertine, wrote it after a life of near-miss accidents — a horse-riding injury, a deadly storm at sea, a stroke — drew him to faith and ministry. In the hymn, modern readers will notice the elongated letter “s,” which looks like a modern “f,” but still be able to easily read the famous first lines:

Amazing Grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

His friend, Cowper, sought religion through his own trials. His hymn “Light Shining Out of Darkness” coined the well-known maxim, “God moves in mysterious ways.” Although he’d published multiple texts and earned acclaim, Cowper suffered from severe depression and made multiple attempts on his own life.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first, blank pages of the Library’s copy of “Olney Hymns,” give the book a personal touch. It describes a coachman’s refusal to drive Cowper to the Thames River, in which he’d planned to drown himself.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first pages of “Olney Hymns,” including his famous line at the end: “God moves in a mysterious way.” Music Division.

Cowper’s handwritten note in the first pages of “Olney Hymns,” including his famous line at the end: “God moves in a mysterious way.” Music Division.Cowper later referred to the incident with a version of the line that is today paraphrased to explain all kinds of uncertainty and distress: “God moves in a mysterious way, his wonders to perform.”

Maybe it was just chance that saved Cowper’s life that day. Or maybe there’s a bit of providence somewhere behind the enduring power of the “Olney Hymns.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 73 followers