Guest Post by Becca Puglisi: On Pacing, the Ultimate Balancing Act

Please welcome Becca Puglisi, one of the authors of the Emotion Thesaurus, who's here to discuss pacing in your writing! Take it away, Becca. :)

I’d like to start this post by stating an opinion that I think pretty much everyone shares: Pacing Sucks. When you get it right, no one really notices. I mean, how many times have you read a 5-star review that went on and on about the awesome pacing? On the other hand, when the pacing’s off, it’s obvious, but not always easy to pinpoint; you’re just left with this vague, ghostly feeling of dissatisfaction. One thing, though, is certain: if the pacing is wrong, it’s definitely going to bother your readers, so I thought I’d share some tips on how to keep the pace smooth and balanced.

1. Current Story vs. Backstory. Every character and every story has backstory. But the relaying of this information almost always slows the pace because it pulls the reader out of the current story and plops them into another one. It’s disorienting. And yet, a certain amount of backstory is necessary to create depth in regards to characters and plot. To keep the pace moving, only share what’s necessary for the reader to know at that moment. Dole out the history in small pieces within the context of the current story, and avoid narrative stretches that interrupt what’s going on. Here’s a great example from Above, by Leah Bobet:

The only good thing about my Curse is that I can still Pass. And that’s half enough to keep me out of trouble. But tonight it’s not the half I need because here’s Atticus, spindly crab arms folded ‘cross his chest, waiting outside my door. His eyes glow dim-shot amber—not bright, so he’s not mad then, just annoyed and looking to be mad.

Bobet could have taken a lengthy paragraph to explain that certain people in this world have curses that are really mutations, that Atticus has crab claws for hands and his eyes glow when he gets angry. But that would’ve slowed the pace and been boring, besides. Instead, Bobet wove this information into the current story—showed Atticus leaning against the door, showed his crustacean claws and his freaky, glowing eyes so the reader knows that he’s a mutant and, to the narrator, at least, this is normal. This is an excellent example of the artful weaving of backstory into the present story

2. Action vs. Exposition/Internal Dialogue. Action is an accelerant. It keeps the pace from dragging. Granted, there will be places in your story that are inherently passive, where characters have to talk, or someone needs to think things out. The key is to break up these places with movement or activity. Characters should be in motion—smacking gum or doodling or fidgeting— while talking. Give them something to do during their thoughtful moments, whether it’s peeling carrots or painting a picture. These bits of action are like an optical illusion, fooling the reader into thinking something’s happening, when really, nothing’s going on. This is one scenario when readers actually prefer to be fooled, so make sure to energize those narrative stretches with action.

3. Conflict vs. Downtime. On the flip side, you can’t have a story that’s all go and no stop. One might think that since action is good, more action is better. Not true. Readers need time to catch their breath, to recover from highly emotional or stressful scenes. A good pace is one that ebbs and flows—high action, a bit of recovery, then back to the activity again. Even The Maze Runner, possibly the most active novel I’ve ever read, has its moments of calm. When it comes to conflict and downtime, a definite balance is needed for the reader to feel satisfied.

4. Keep Upping the Stakes. We know that conflict is important—so important that every single scene needs it. But for conflict to be effective, it needs to escalate over the course of the story. To keep the reader engaged, each of the major conflict points needs to be bigger, more dramatic, and with stakes that are more desperate. Look at The Hunger Games. It starts with Prim in danger, followed by Katniss facing a series of do-or-die scenarios, and finally ends with her playing a desperate game of life or death with not only herself, but Peeta, too. Clearly, lots of other conflict is interspersed, but when it comes to the major points, each one should have greater impact than the last.

5. Condense the timeline. When possible, keep your timeline tight. If it gets too spread out, the story will inevitably drag. It’s also hard, in a story that covers a long span, to keep things smooth; there will be time jumps of weeks or months or even years between scenes. Too many of these give the story a jerky feel. So when it comes to the timeline, condense it as much as possible to keep the pace steady.

For sure, pacing is tricky, but I’ve found these nuggets to be helpful in maintaining a good balance. What other tips do you have for keeping your story moving at the right pace?

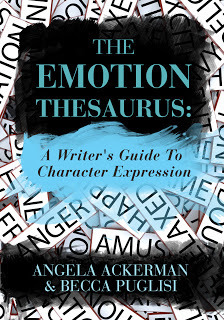

Becca Puglisi is one half of The Bookshelf Muse blogging duo, and co-author of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer's Guide to Character Expression. Listing the body language, visceral reactions and thoughts associated with 75 different emotions, this brainstorming guide is a valuable tool for showing, not telling, emotion. The Emotion Thesaurus is available for purchase through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, iTunes, and Smashwords, and the PDF can be purchased directly from her blog.

Becca Puglisi is one half of The Bookshelf Muse blogging duo, and co-author of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer's Guide to Character Expression. Listing the body language, visceral reactions and thoughts associated with 75 different emotions, this brainstorming guide is a valuable tool for showing, not telling, emotion. The Emotion Thesaurus is available for purchase through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, iTunes, and Smashwords, and the PDF can be purchased directly from her blog.

Published on August 02, 2012 01:30

No comments have been added yet.