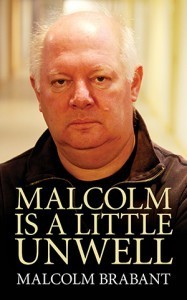

Interview with Malcolm Brabant

Malcolm Brabant was a television journalist and war correspondent for the BBC for over twenty years. That is, until he became seriously ill following a vaccination against yellow fever in 2011. In his new book, Malcolm is a Little Unwell, he details his battle with psychosis and serious mental illness as a result of the vaccination.

Malcolm Brabant was a television journalist and war correspondent for the BBC for over twenty years. That is, until he became seriously ill following a vaccination against yellow fever in 2011. In his new book, Malcolm is a Little Unwell, he details his battle with psychosis and serious mental illness as a result of the vaccination.

Book blurb

The book chronicles a Kafkaesque journey through insanity during which Brabant first believes he is the Messiah and later, the Devil. He imagines he is visited by guardian angels, close friends and relatives who died premature deaths, and who set him impossible tasks to prove that he was the Chosen One. At his lowest point, certain he is possessed by Lucifer while in a locked psychiatric ward, Brabant, an award winning veteran BBC foreign correspondent, attempts suicide in order to save the world.

His illness causes him to lose his job as the Corporation’s Athens correspondent, and his family comes within a whisker of being homeless. As doctors try to find the right combination of medication to cure his fried brain, Brabant’s wife Trine struggles to restore him to the alpha male husband she married while taking on Sanofi Pasteur, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of the yellow fever jab. Her love and anger are the driving forces as the family struggles to crawl from the abyss and embarks on a David versus Goliath battle to win justice.

(My questions are in bold; Malcolm’s answers in regular type.)

Through my own experiences with mental health problems I’ve read and written a lot about different forms of psychological illness, but reading about your experience after receiving the yellow fever jab was harrowing to say the least. Just how disturbing was it at the time? Or did it feel absolutely normal to you in that mindset?

Good question. The first time I thought things were getting unreal was while I was in Ygeia hospital in Athens. I was suffering from a dangerously high temperature and I saw my Kindle e-reader fly across the room from my bed to a chair. Experts would say I was suffering from hallucinations, but I suddenly thought I had some supernatural powers, that a part of my brain was capable of doing things that others were incapable of. I didn’t feel disturbed at the time, as far as I can recall. But what I wanted to do was to explore the adventure that seemed to be unfolding.

Malcolm with his wife, Trine

My wife believes I started to slide mentally before this event, when I was uncharacteristically aggressive towards a doctor. I had merely shouted at him and ordered him out of my room after he asked what I regarded as some offensive questions. What I was feeling all the way through this was weariness and discomfort because the fever would not dissipate.

To go through something like that is one thing, but to believe that you are absolutely fine has to be so much more disturbing. How were you able to live during that time? For me, writing about mental illness whilst in the throes of its darkest hours was something which helped me achieve a sense of realism in the writing. Were you able to do this or did the severity of the condition mean you had to write retrospectively?

All throughout the period of madness I was aware that I was living an extraordinary story. During my first relapse in Athens, when I slipped back into a mystical belief that I was perhaps a new generation “wise man” I had the wit to film what I was doing on my video camera. It helped provide a precise record of what I was doing and thus was a source of invaluable material. When I was in hospital periodically, I also took notes and wrote an incomplete diary. My wife also kept a video diary which was crucial when it came to writing the book. The majority of the book, perhaps 85 percent was written when I was sane or ‘in remission’.

Your years as a television news reporter in some of the most war-torn corners of the world have made writing about difficult subjects second-nature to you. Just how different and difficult was it to write about such a harrowing personal experience?

Malcolm interviewing mujahedeen fighters in Central Bosnia on a captured Croat tank in 1993

I didn’t find it a harrowing experience writing about what happened to me. I was able to detach myself to a degree and deploy my journalistic instincts. Part of the process of writing the book involved interviewing my wife Trine in depth. She has a photographic memory and her input was essential. During the course of our discussions she frequently broke down and cried. Her tears contributed to the most upsetting part of writing, and also rammed home what had happened to me and my family.

Was it difficult to detach from the situation? I can imagine that seeing the impact the experience had on your loved ones would make it very difficult to tackle. Or did your journalistic instincts really take over?

I didn’t become emotional when I wrote the book. My wife was astonished by my concentration. I was very focussed. I would sit down for four, five or six hours at a time and hammer away. I needed to be strong to write the book, and I was ruthless about trying to piece together the events that overwhelmed me during my madness. I was determined that the book should be as accurate and transparent as possible. And I have my journalistic credo to thank for that.

You’re a stronger man than I am! The book’s not just the story of how you ‘went mad’, but also a story of love, familial destruction and hope in the face of personal disaster. You touched on it earlier, but what effect did your experience have on your family and wider social network?

The madness had a devastating effect on my family. For my wife it was a dreadful case of déjà vu. Her father suffered serious psychiatric problems and was kept locked up in the same secure ward in Copenhagen as I. He committed suicide after being let out and it was dreadful for her to have to suffer the knowledge that I had made an attempt to kill myself, albeit unsuccessfully.

Malcolm’s son, Lukas

It also had a terrible impact on my 12-year-old son Lukas. He was an innocent young lad before April 2011, and then suddenly he learns that his father believes he’s Jesus and that he, Lukas will also one day become the Messiah. It made him grow up in an instant. We’re afraid of the long-term impact on him, and fear he may have some form of delayed post traumatic stress disorder.

However, my family is emerging from this experience tougher, although badly bruised. One thing that was most uplifting was the fact that my friends and their networks rallied around me to provide moral support and to ensure that I don’t feel stigmatized by my illness. It’s been nearly a year since I left hospital and there has been no sign of a relapse. And also, what’s been good is that nobody has treated me as if I was a psychiatric case. People have taken me at face value.

Having caused that sort of personal impact on your life, what message do you think the book can give in today’s society?

There are several messages which the book can deliver. One is about vaccine safety and that is when something goes wrong it has be thoroughly investigated and there must be corporate responsibility. The second is that mental illness can happen to anyone. People should remember that the next time they bump into someone in the street who is acting a little strangely.

The third is that the power of love can go a long way to overcoming the deepest of problems. I was blessed to have the unwavering support of my wife and son as well as my ‘cloud’ of friends.