Defining The Lady Code

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post called “The Lady Code.” In it, I pointed out that there is still a “lady code,” an implicit code by which we determine whether or not a woman is a lady. This code dates back to at least the Victorian era: in Victorian novels, characters always seem to know, immediately, whether or not a woman is a lady “by her dress and manner.” (I don’t remember where those words come from, but most likely a Sherlock Holmes story?)

Here is what I wrote in my last blog post: “In American, we are raised with an implicit lady code, because we tend not to talk about social status. But upper-middle class girls are educated into it: they are taught what to wear, usually by their mothers. They are taught which skirts are too short, which shirts too tight. They are taught to signal their social status in coded ways.” I added, “So dressing, for a woman, is a complicated affair. When you look into your closet in the morning — and even before that, when you buy your clothes in a store or online — you are making a choice about what you want to communicate. You are speaking in a coded language. If you were raised by an upper-middle-class mother, you know the lady code. You are fluent in that particular language. You know that what you wear should vary depending on the occasion. You will not wear a cocktail dress to the ballet.”

I’ve wanted to write more about this topic for a while, because I’m fascinated by the various ways we communicate, including through clothes. And what I’ve wanted to focus on is that last bit: not wearing a cocktail dress to the ballet. In other words, the details of the code. You see, I was born in Europe, so a lot of the code, and how it applied in a modern American context, I had to figure out for myself. My mother was very strict about how I dressed, but her ideas came from her own mother, who was a lady in the old European sense. What I learned was very old-fashioned. How old-fashioned? As a child, I was taught to embroider, because that is what girl children learned . . . My grandmother told me that only gypsies wore earrings. That old-fashioned.

But I had to learn how to dress, and how dress codes operated, because I was trying to present myself as an educated, employable woman in modern America: first as a lawyer, and then as a professor. This post is about what I learned, how I think the code works: what upper-middle-class women teach their daughters, and what I will probably teach my own daughter. (Please note that in this post I am neither criticizing the code nor saying that anyone should follow it. I’ve rebelled against it plenty myself: when I was sixteen, I pierced my own ears, with safety pins. But the code exists, and we are judged by it. So I’m trying to understand it.) Here are some of its basic tenets:

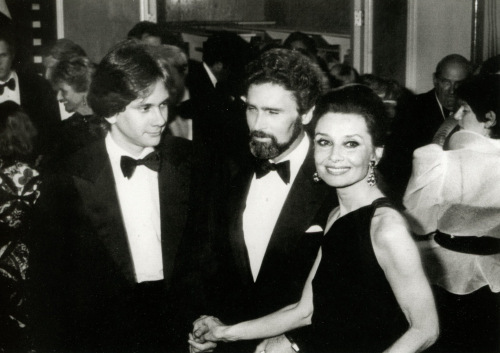

(The images in this blog post are all, obviously, of Audrey Hepburn. I chose them because she is such a perfect representative of the lady code, partly in how she was presented by Hollywood, but mostly in what she herself chose to wear. So I’ve selected photographs in which she at least seems to have been caught off guard, in her own clothes.)

1. Your clothing should be appropriate for the occasion. You actually find this explicitly stated in Agatha Christie stories, where Hercules Poirot has some wonderful pronouncements about what ladies do and don’t wear. A lady, he says, will always dress appropriately: she will not wear city clothes in the country or vice versa. I would say that dressing inappropriately for a particular context marks you as not understanding that context, whether it’s the ballet or, more importantly, a job interview. It signals that you don’t understand the code at work in the situation. What it sometimes means is that you don’t get the job, and that is, after all, the lady code’s most important ramification nowadays: it affects employment prospects. But more broadly, a woman who is what we call well-dressed will wear rain boots in the rain, flip-flops at the beach rather than on city streets. She will be dressed “appropriately.”

2. Your appearance, including makeup, should be “natural.” By “natural” I don’t mean natural: culturally, we actually think of a bare face, a face with no makeup on it, as a rebellion against social norms. (Which is ironic, since in the Victorian era, a woman wearing makeup would not be considered a lady. Oh, women did wear makeup, but it had to be so discreet as to be almost invisible. And never mentioned!) “Natural” means that you look like the cultural idea of natural: discreet makeup, hair a color that could be natural even though it’s probably not. Nails neatly trimmed but either unpainted or, if painted, a light color that looks, at first glance, like a natural nail. No obvious tattoos. (Tattoos on women have become more accepted recently. But socially, they are still judged. They will still affect important aspects of one’s life, such as job prospects. They remain markers of social class.)

3. Your jewelry and other accessories should be discreet. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, where the lady code was simply what most undergraduate women wore most days, I heard a boy from a small Southern town say that a woman should never wear more than five pieces of jewelry. He gave as an example a watch, two earrings, a ring, and a bracelet. And I still remember an article in which Miss Manners (remember Miss Manners?) was asked where it was appropriate to wear an anklet (remember anklets?). She said: on the wrist, where it is called a bracelet. Coco Chanel popularized long ropes of fake pearls, but she was a fashion designer, and a lady is not fashionable. She has style, which is a different thing altogether. Fashion stands out: style is discreet and understated. At UVA, all the undergraduate women seemed to wear a single strand of real pearls, perhaps because they had all gotten one when they turned sixteen. I did myself, as my sixteenth birthday present . . .

4. This is a complicated one: you should look feminine but not sexual. Got that? This is one of the reasons the lady code is so often criticized: it’s nuanced and complicated. And it can be used to shame women: I still remember being at a funeral at a small town in the South and hearing two women talk about a third, who had worn a black suit that had obviously not been meant for a funeral. The fit was too tight, and it showed cleavage. It was sexy. I remember that it was worn with very high stiletto heels . . . On the other hand, one thing I find useful about the code, myself, is that when I dress according to it, my body becomes functionally invisible. I am seen as a teacher or lawyer, not as a potentially sexual woman. I am not hit on . . . So the code cuts both ways, and I suppose that’s why it’s survived. It is, in one sense, a means of social control. But in another, it’s a way that women have controlled how they are perceived. And by the way, skirt length? Between the lower calf and just above the knee. Anything shorter is perceived as sexual; anything longer is perceived as properly for evening.

5. You should have style, but not be fashionable, and your clothing should signal quality, even if you bought it at Goodwill. About half of my closet comes from Goodwill . . . This is a complicated one too, isn’t it? And men wonder why women have so many clothes! By fashionable, I mean whatever is “in” this season. I teach at a very fashionable university, and I still remember the semester every undergraduate woman wore culottes. It was the semester of the culottes. By next semester, the culottes were gone, and my fashionable undergraduates would not have been caught dead in them. Dressing stylishly means dressing in a way that is timeless, and by timeless I mean in a style that has lasted for at least ten years. (That’s now long timeless is in fashion.) A white blouse, slim jeans, ballet flats, and patterned scarf would have been as appropriate on Audrey Hepburn as they are now. Another of Hercules Poirot’s wonderful statements is that whatever else she may look like, a lady will wear good quality shoes. (He solves a case because a woman pretending to be Lady Somebody is wearing cheap shoes. I kid you not.) This, by the way, is part of the reason jewelry should be discreet: because unless you are the Queen of England or Elizabeth Taylor, large jewelry inevitably looks fake, even when it’s not. Small jewelry looks real, even when it’s not. And quality is often tied to the idea of authenticity: real linen, real leather, real pearls.

I think that’s enough for now, and do realize that this list is a work in progress. It is my attempt to figure out how this language of clothes works, how we perceive dress. There are all sorts of codes — for different disciplines, for example, so that a female scientist will be expected to dress a particular way, which is different from a female elementary school teacher, and different from a female lawyer. But the lady code is a fairly broad, underlying social code that has a lot to do with how women are judged in our culture, which is why I wanted to explore it in more detail. How do I dress? Mostly the way I’ve described above, although my clothes are a little more bohemian, because they’re allowed to be. I’m a writer and a professor. I get to be a little artsy. But I do have to be conscious about how I’m perceived, because I’m often “on”: for students, colleagues, readers.

There’s a lot more to say about the above. Dress codes can operate in very different ways depending on race, social class, and other factors, and those are certainly worth exploring, although I haven’t said anything about them here. And there are people who can afford to ignore dress codes altogether. They tend to be the wealthy, who don’t need to work, or people who work in ways that give them a great deal of independence in defining their own looks, although they often have codes of their own. If you are a tattoo artist, you’d better have tattoos, and they’d better be good ones. Very few of us exist outside of these codes altogether, just as very few of us exist outside language. They are ways we communicate, sometimes deliberately, sometimes inadvertently. Which is part of what makes them so fascinating . . .

(And if you want to know whether something you’re planning on wearing is “ladylike”? Ask yourself if Audrey Hepburn would wear it. I think that’s a pretty reliable test . . .)