A Simple Diet

I decided to write this blog post because whenever I go into the bookstore, I see books on diets, most of them filled with advice that I think is actually harmful. And whenever I go on social media, I see friends going on diets, which may or may not help them. I’ve also had friends ask me how I stay in shape, and say to me, “You must be one of those people who can eat anything she wants.” No, I can’t. I have a long history of going on diets of various sorts, back to my teenage years. None of them worked or helped me, and it took me a long time to figure out a way to eat that is healthy and makes me happy, both with myself and the food I’m eating.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you’ll know that I like to figure things out: my life is so busy that I like to figure out how to make parts of it as simple and intuitive as possible. Like cleaning, or exercise. I like to hack my own life and happiness. I want it to be easy so I can spend time on the things that really matter: my teaching and writing, my daughter and other relationships.

So how did I figure out how to maintain what I feel is a healthy weight for me, and more importantly, find a way of eating that gives me energy and makes me happy? Because if a diet (I use the word here to mean a way of eating, not a way of losing weight) doesn’t give you energy and make you happy, it won’t be your diet for much longer. It’s very hard to motivate yourself to do anything that makes you tired and unhappy — and honestly, those are signs that whatever you’re doing is unhealthy anyway.

I’ll start with my premise: no one diet is healthy and effective for everyone. We are all unique, with unique cultural and personal histories, as well as unique tastes. This is why I call foul on diet books: they tell us that everyone should be following one (their) diet. But I have a friend who was trying to lose weight, and simply could not — until she realized that she was lactose intolerant. She had to cut out dairy products entirely before she could find a weight that felt right for her. On the other hand, I’ve been told and have read that dairy products are unnecessary for adults, and that I would be healthier if I cut them out of my diet. So I tried, but it was as though my body said to me, “What do you think you’re doing?” I got sick. I was so used to following “expert” advice that it took me a while to realize what I should have understood about myself: my ancestors were nomadic horsemen. They lived on the milk from their herds for a thousand years. Without dairy products, they would not have survived. I have the body that evolved in that environment: I’m short, slight, compact. I gain weight easily, but I also gain muscle easily. I’m good at things like gymnastics and riding horses, and terrible at things like running, especially long distances. My friend and I have different bodies: mine needs diary products. One diet will not work for both of us.

So if the diet books are expensive wastes of time, how do you figure out a diet (as a way of eating) for yourself? I do think it’s important to figure it out, because we live in an environment we weren’t designed for. We evolved to eat in environments in which finding food was difficult — we had to hunt or grow it, and then prepare it. We exercised regularly simply as part of our daily lives. Obviously, we don’t live in that environment anymore. So if we want to be healthy, most of us need to be conscious about our food choices. This is how I did it, which may or may not work for you:

1. Learn about yourself.

When I realized that I kept trying different diets, none of which made me feel healthier or helped me lose weight (which was my real concern — it should not have been, but it was), I started to keep a food journal. I wrote down what I ate, when, and why. And I kept track of calories. Keeping a food journal taught me things about my body that I had not realized before. First, it made me confront the fact that my body was very precise about weight, which makes sense. After all, it’s precise about maintaining my temperature, my hormone levels . . . If I ate around 1600 calories a day, it would slowly lose weight. If I ate around 1800 calories a day, it would slowly gain weight. Between those two numbers, my weight would stay around the same. And it didn’t much matter what I ate, in terms of weight: my body cared about calories. But I also learned that what I ate mattered a great deal in terms of my energy level. White bread and sugar made my energy level rise, but then it would crash suddenly several hours later and I would be hungry again. Whole wheat bread, especially if I ate it with cheese, would give me energy for a whole afternoon. I found dark chocolate more satisfying than milk chocolate: I could eat a little and not want more. Raw sugar and white sugar affected me differently, probably because raw sugar had a more complex and therefore satisfying flavor.

And I learned about myself psychologically. I learned that I ate when I was hungry, but also when I was bored, or anxious, or depressed. I learned that I ate to give myself a treat. Food is an excellent way to deal with hunger, but a terrible way to deal with boredom, anxiety, or depression, because it doesn’t actually help. I had to find other coping mechanisms. And I found other treats to give myself: makeup, books, walks in the park. I found that in order to eat healthily, for hunger and not other reasons, I had to actually take better care of myself as a person. I also learned that I eat when I’m tired, to substitute for sleep. Also not a good idea. I still do this sometimes, but at least I recognize that I’m doing it, and when I gain weight after a week of late night snacks, I’ll know why.

I also learned about my habits, tastes, and preferences, which are just as important as learning about yourself physically and psychologically. For example, I don’t particularly care about cooking as an art, or fancy food. A bowl of pasta with sauce and cheese for dinner makes me perfectly happy. When I bake, it’s usually banana bread or brownies. Going out to a restaurant is fun as a treat, but otherwise I’m not interested in gourmet cooking. I have friends who are, and they need to take that into account when create their own preferred diets. On the other hand, I have a serious sweet tooth, and if I don’t indulge it on a fairly regular basis, I’m unhappy. So I have to make sure that my diet includes chocolate on a regular basis . . .

In a way, I hacked myself, which would have been a useful exercise even if it hadn’t led to a change in my diet and my attitude toward food.

(Breakfast: oatmeal with milk and raisins, orange juice with fizzy water, chai latte.)

2. Create your own system.

I’ve used “diet” in this blog post in two ways: as a way of losing weight, and as a way of eating. Here I mean a way of eating. Whether or not you want to lose weight is up to you, and between you and yourself. No one else is part of that conversation. But what I can say with some confidence is that losing weight as a goal does not work if it relies on changing what you eat temporarily, until you reach your “goal.” What I’m talking about is not reaching a goal but creating a new system, a way to eat that you will follow. So it needs to make you healthy and happy, to give you energy.

My diet is pretty simple. It’s a mix of grains, meats, dairy, vegetables, and fruit. The grains are whole wheat: brown rice and pasta, and whole wheat bread, because of the havoc that the white stuff wreaks on my energy levels. The meats are usually lean. The dairy is usually low fat (like 2% milk), but I don’t eat anything fat-free. I buy bags of frozen vegetables, steam them, and add butter. And the fruit is usually fresh, unless I buy frozen fruit and make something like peach crisp. I have raw sugar in my oatmeal and tea, honey in my yogurt (which I buy plain). I eat four meals a day: breakfast, lunch, snack, and dinner. The snack includes chocolate, and the dinner includes dessert (although it’s usually something like yogurt with honey, or a slice of banana bread). I try to make sure that each meal includes different types of food: grains, proteins, vegetables or fruit. I find that a combination feels me fuller and more satisfied than any food alone. Oh, and I use butter and canola oil for cooking.

I eat mostly simple, unprocessed food that I cook myself. I’m a creature of habit, so breakfast is usually oatmeal with milk and raisins, orange juice with fizzy water, and a chai latte. Lunch is usually a cheese sandwich on whole wheat bread and an apple, which I can carry with me and eat between teaching classes. Snack varies, but almost always includes chocolate as well as healthier things, like dried fruit. And dinner is usually brown rice or pasta with vegetables and meat or cheese, plus dessert. And then always a mug of herbal tea before bedtime.

I still keep a simple food journal: what, when, and calories. It’s a way of making sure that I’m conscious about my food choices, not a way of controlling what I eat. I usually stay in the 1600-1800 calorie range, because that’s where I’m not hungry, where I have lots of energy, where I feel at my best. But if I’m hungry, I always eat. There are times when I’m under stress, or very active, when I simply need more calories, or more protein, or even more chocolate . . .

And I schedule treats. Once I week, I make sure I have something extravagant that I don’t usually have — today, for example, it will be ice cream at a shop that opened downtown. A very fancy shop. When I have treats, I make them count!

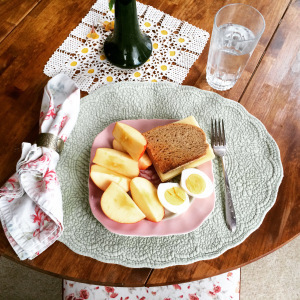

(Lunch: cheese sandwich, hard-boiled egg, apple.)

3. Follow it most of the time.

This one is pretty self-explanatory. Once you’ve developed your system, one that makes you healthy and happy, one in which you don’t have to give up any food you want to eat (although you may need to eat it in moderation), just follow it most of the time. Goals are problematic because you spend most of your time feeling as though you need to reach your goal, you haven’t reached your goal, your goal is out of reach . . . A system is better because you can congratulate yourself for sticking with a system that is making you healthier and happier. And if you go away from it for a while, you can go back to it. You can’t go back to a goal, by definition.

Even better, you can build exceptions into the system. I try to follow my own way of eating, my own diet, most of the time. But if I’m at a restaurant with friends, I’ll have a wonderful meal, whatever it consists of. A burger, sushi, tapas . . . I’ll have the best meal I can. And then the next day I’ll go back to eating the way I usually do.

So that’s it, really. We live in an environment in which we’re getting conflicting messages about food all the time. We see advertisements telling us how much fun it would be to have dinner at Olive Garden, and diet books telling us that we have to cut out X, Y, or Z foods, or live like our Neolithic ancestors (while giving us completely inaccurate information on what they ate). Or cut out “toxins.” We’re caught between two damaging messages.

Sometimes I wish I could write a diet book to counteract all the diet books I see on the bookstore shelves! It would probably not sell very well, though. It would consist of these very simple messages:

We live in an environment in which to be healthy, most of us need to be conscious about what we eat. We are bombarded with messages, most of which are not helpful. You are yourself, different from anyone else. What works for me may not work for you. In this, as in everything else, you will need to find your own way. Here’s how:

1. Learn about yourself.

2. Create a system you can follow.

3. Follow it most of the time.

(Dinner: whole wheat pasta with marinara sauce and parmesan, broccoli with butter. Dessert was plain yogurt with honey.)