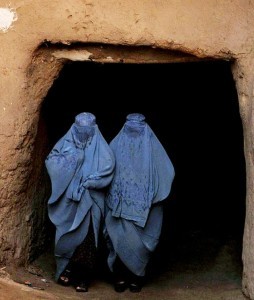

Sisters on the Hill of Widows

When night falls on Tapaye Zanabad, one of the hills surrounding Kabul, women appear with shovels and sieves. They work in the dark, digging in the mud to shape bricks with their bare hands to build adobe houses.

Tapaye Zanabad means ‘built by women’ in Dari, the local language, but the steep, featureless incline is now more commonly known as the Hill of Widows.

The women living on the hill lost their husbands in more than thirty years of continuous conflict in Afghanistan – the war against the Russians; the civil war between the Mujahedeen and the Taliban; the war the Americans brought with promises of democracy, and the war women fight every day just for being born a woman.

In a population of 30 million, there are in Afghanistan between 1.5 and 2 million widows. The men who died in the wars were mostly young men who left behind young widows, usually with children. It is the custom for widows to remarry, routinely to a family member of the dead fighter, and many have become widows a second time.

In Afghanistan, a woman belongs to the head of the family, her father or husband. A widow is a burden cruelly called ‘a saucepan without a lid.’ Women who have lost two husbands are considered unlucky and face intolerable choices: men prepared to marry them seldom want to take on their children, while to live alone, or make a living by one’s own means, runs against the strict traditions of the country.

Women who do not submit to their families are often killed by them. Those who escape are social outcasts, and can never return to their villages. Women who flee to Kabul, the capital, find their way to the Hill of Widows, where more than 1,000 women and several thousand children have built a unique village of shanty houses and a community of ‘sisters’ struggling to create a future.

Hill of Widows Dangers

The hill belongs to the military. To remind the women that they are squatters, the police have always come with long sticks to smash a few heads and remind them that they are breaking the law, as well as Afghan conventions. The reason why they build at night.

The women are not expelled. There are no facilities for so many widows and their children, a fact that has brought new confidence to the community. With aid from international charities, five years ago, the women dug trenches and laid pipes for water. A year ago, in 2014, cables strung from roof to roof brought the first electric lights.

The majority of the women are unskilled and illiterate; in spite of the wars and promises, there are still few schools for girls in Afghanistan. The widows beg in the streets, launder clothes or work as cleaners. When two women were employed to clean the police station at the bottom of the hill, the police learned their stories and stopped climbing the slopes with their long sticks.

At the beginning of 2015, Shakria Jalalzay, an Afghan activist, obtained a grant of 18,000 euros from a Spanish charity to buy sewing machines and set up a workshop. In August, twenty women were chosen to take part in an intensive five-month course to learn how to read, write and work the machines. In December, they will receive certificates as qualified seamstresses and leave with skills to make a living and teach other women.

Shakria Jalalzay’s ambitions do not end there. She is negotiating for funds to take another forty widows through the course in 2016. ‘The project is to empower Afghani women condemned to a life of dependence and marginalization to be self-sufficient,’ she told the El País newspaper.

Ambition is catching. The women have started laying rugs and painting their mud houses in bright colours. Plastic sheets cover the windows, but they dream of glass and are working to make their dreams come true. The Hill of Widows is now a village, a community. The sisters welcome new widows, listen to their stories of suffering and loss, and work in teams shifting war debris to build new houses.

It has always been the custom in rural Afghanistan that women leave their home only twice. Once to marry and move into their husband’s house, the second time to be buried. That is changing. By taking control of their own lives, the widows have shown that women can be economically productive and survive on their own.

The government has finally plugged the community into the mains water and electric supply, an acknowledgement that the women on the hill are there to stay. This was the last token of encouragement they needed to begin legal proceedings to acquire deeds for the houses they built with their own hands.

After thirty years of war, the sisters on the Hill of Widows have created their own means of survival and an economic and social model governments in developing nations would do well to study – just ask the women. They usually know best.

Please share with the links below.

The post Sisters on the Hill of Widows appeared first on Erotic romance writer Chloe Thurlow.