The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Woodrow Wilson

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

WOODROW WILSON: A BIOGRAPHY - GLOSSARY (SPOILER THREAD)

1916 Presidential Election Results

1916 Presidential Election Results

The United States presidential election of 1916 was the 33rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1916. Incumbent President Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic candidate, was pitted against Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican candidate. After a hard-fought contest, Wilson defeated Hughes by nearly 600,000 votes in the popular vote and secured a narrow Electoral College margin by winning several swing states by razor-thin margins. As a result, Wilson became the first Democratic president since Andrew Jackson to be elected to two consecutive terms of office.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_S...)

More:

http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/na...

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/showel...

(no image) The Presidential Election of 1916 by S. D. Lovell (no photo)

(no image) Wilson, Vol. 5: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace, 1916-1917 by Arthur S. Link (no photo)

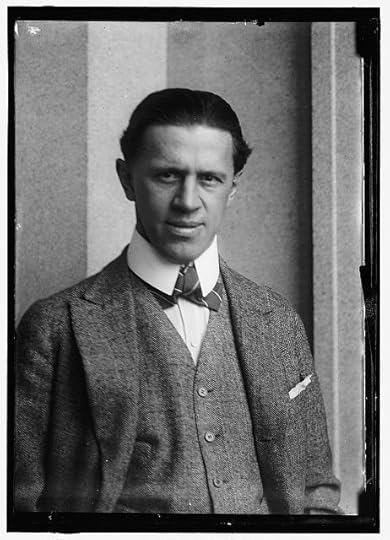

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (1870-1965) was often referred to as the "elder statesman" because through three wars the presidents of our country called upon him for his advice and expertise.

Baruch was born on August 19, 1870, the second of four sons of Belle and Simon Baruch. His father was a field surgeon for the Confederate Army during the Civil War. In 1881, the Baruchs moved to New York City, where his father continued his medical career as a general physician specializing in appendicitis and hydrotherapy.

Bernard and his brothers went to the public schools in New York City. He was quite active in sports at the College of the City of New York. It was during a collegiate baseball game that he injured an ear, which impaired his hearing. After graduating from college, he went through many jobs until he accumulated enough money to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. His financial acumen made him a millionaire at the age of 30.

Baruch was a devoted member of the Democratic Party and contributed generously to it. When Woodrow Wilson became president, Baruch was a frequent visitor to the White House. During World War I, President Wilson appointed him to the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense. Accepting the appointment, Baruch resigned his positions with industry, liquidated his holdings and sold his seat on the Stock Exchange. He bought millions of dollars of Liberty Bonds.

Baruch played an active role on many government commissions. After the war, he went with President Wilson to the Versailles peace conference. He also played active roles in the administrations of Presidents Harding and Hoover, and was a member of the "Brain Trust" in President Roosevelt's "New Deal." In the early 1930s, Baruch urged the stockpiling of rubber and tin, which are necessary items for war. Baruch anticipated that the United States would be involved in World War II and constantly urged our government to build up the armed forces.

During World War II, Baruch was involved in many committees for the war effort. He did his best thinking sitting in the parks of Washington, D.C., and New York City. He could always be seen with other people discussing affairs of the government on a park bench, which became his trademark. During the Korean War, Baruch called for an expansion of the Voice of America to counteract the enemy propaganda.

(Source: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/j...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_...

http://www.trumanlibrary.org/hoover/b...

http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/library/al...

& (no image) The Public Years & (no image) A Philosophy For Our Time by

& (no image) The Public Years & (no image) A Philosophy For Our Time by

Bernard M. Baruch

Bernard M. Baruch by James Grant (no photo)

by James Grant (no photo) by Daniel Alef (no photo)

by Daniel Alef (no photo) by Margaret L. Coit (no photo)

by Margaret L. Coit (no photo) by Jordan A. Schwarz (no photo)

by Jordan A. Schwarz (no photo)(no image) Bernard Baruch, Portrait of a Citizen by William Lindsay White (no photo)

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

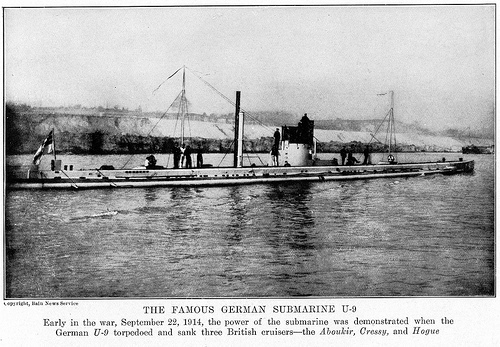

On February 1, 1917, the lethal threat of the German U-boat submarine raises its head again, as Germany returns to the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare it had previously suspended in response to pressure from the United States and other neutral countries.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was first introduced in World War I in early 1915, when Germany declared the area around the British Isles a war zone, in which all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. A string of attacks on merchant ships followed, culminating in the sinking of the British ship Lusitania by a German U-boat on May 7, 1915. Although the Lusitania was a British ship and it was carrying a supply of munitions—Germany used these two facts to justify the attack—it was principally a passenger ship, and the 1,201 people who drowned in its sinking included 128 Americans. The incident prompted U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to send a strongly worded note to the German government demanding an end to German attacks against unarmed merchant ships. By September 1915, the German government had imposed such strict constraints on the operation of the nation's submarines that the German navy was persuaded to suspend U-boat warfare altogether.

German navy commanders, however, were ultimately not prepared to accept this degree of passivity, and continued to push for a more aggressive use of the submarine, convincing first the army and eventually the government, most importantly Kaiser Wilhelm, that the U-boat was an essential component of German war strategy. Planning to remain on the defensive on the Western Front in 1917, the supreme army command endorsed the navy's opinion that unrestricted U-boat warfare against the British at sea could result in a German victory by the fall of 1917. In a joint audience with the kaiser on January 8, 1917, army and naval leaders presented their arguments to Wilhelm, who supported them in spite of the opposition of the German chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, who was not at the meeting. Though he feared antagonizing the U.S., Bethmann Hollweg accepted the kaiser's decision, pressured as he was by the armed forces and the hungry and frustrated German public, which was angered by the continuing Allied naval blockade and which supported aggressive action towards Germany's enemies.

On January 31, 1917, Bethmann Hollweg went before the German Reichstag government and made the announcement that unrestricted submarine warfare would resume the next day, February 1. The destructive designs of our opponents cannot be expressed more strongly. We have been challenged to fight to the end. We accept the challenge. We stake everything, and we shall be victorious.

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...)

More:

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unrestri...

http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/u...

http://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Germ...

by Malcolm Llewellyn-jones (no photo)

by Malcolm Llewellyn-jones (no photo) by Gordon Williamson (no photo)

by Gordon Williamson (no photo) by R.H. Gibson (no photo)

by R.H. Gibson (no photo) by

by

Henry Newbolt

Henry Newbolt by Georg-Gunther von Forstner (no photo)

by Georg-Gunther von Forstner (no photo)

Wilson's 1916 Annual Message, Part One

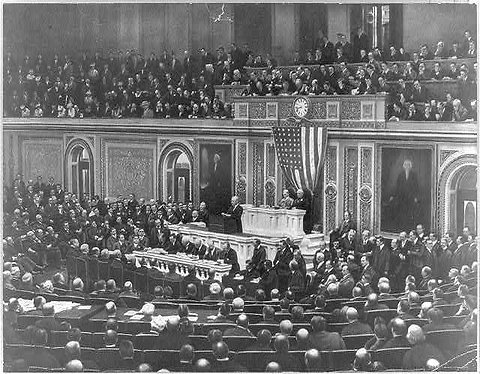

Wilson's 1916 Annual Message, Part OneGENTLEMEN OF THE CONGRESS:

In fulfilling at this time the duty laid upon me by the Constitution of communicating to you from time to time information of the state of the Union and recommending to your consideration such legislative measures as may be judged necessary and expedient, I shall continue the practice, which I hope has been acceptable to you, of leaving to the reports of the several heads of the executive departments the elaboration of the detailed needs of the public service and confine myself to those matters of more general public policy with which it seems necessary and feasible to deal at the present session of the Congress.

I realize the limitations of time under which you will necessarily act at this session and shall make my suggestions as few as possible; but there were some things left undone at the last session which there will now be time to complete and which it seems necessary in the interest of the public to do at once.

In the first place, it seems to me imperatively necessary that the earliest possible consideration and action should be accorded the remaining measures of the program of settlement and regulation which I had occasion to recommend to you at the close of your last session in view of the public dangers disclosed by the unaccommodated difficulties which then existed, and which still unhappily continue to exist, between the railroads of the country and their locomotive engineers, conductors and trainmen.

I then recommended:

First, immediate provision for the enlargement and administrative reorganization of the Interstate Commerce Commission along the lines embodied in the bill recently passed by the House of Representatives and now awaiting action by the Senate; in order that the Commission may be enabled to deal with the many great and various duties now devolving upon it with a promptness and thoroughness which are, with its present constitution and means of action, practically impossible.

Second, the establishment of an eight-hour day as the legal basis alike of work and wages in the employment of all railway employes who are actually engaged in the work of operating trains in interstate transportation.

Third, the authorization of the appointment by the President of a small body of men to observe actual results in experience of the adoption of the eight-hour day in railway transportation alike for the men and for the railroads.

Fourth, explicit approval by the Congress of the consideration by the Interstate Commerce Commission of an increase of freight rates to meet such additional expenditures by the railroads as may have been rendered necessary by the adoption of the eight-hour day and which have not been offset by administrative readjustments and economies, should the facts disclosed justify the increase.

Fifth, an amendment of the existing Federal statute which provides for the mediation, conciliation and arbitration of such controversies as the present by adding to it a provision that, in case the methods of accommodation now provided for should fail, a full public investigation of the merits of every such dispute shall be instituted and completed before a strike or lockout may lawfully be attempted.

And, sixth, the lodgment in the hands of the Executive of the power, in case of military necessity, to take control of such portions and such rolling stock of the railways of the country as may be required for military use and to operate them for military purposes, with authority to draft into the military service of the United States such train crews and administrative officials as the circumstances require for their safe and efficient use.

The second and third of these recommendations the Congress immediately acted on: it established the eight-hour day as the legal basis of work and wages in train service and it authorized the appointment of a commission to observe and report upon the practical results, deeming these the measures most immediately needed; but it postponed action upon the other suggestions until an opportunity should be offered for a more deliberate consideration of them.

The fourth recommendation I do not deem it necessary to renew. The power of the Interstate Commerce Commission to grant an increase of rates on the ground referred to is indisputably clear and a recommendation by the Congress with regard to such a matter might seem to draw in question the scope of the commission's authority or its inclination to do justice when there is no reason to doubt either.

The other suggestions-the increase in the Interstate Commerce Commission's membership and in its facilities for performing its manifold duties; the provision for full public investigation and assessment of industrial disputes, and the grant to the Executive of the power to control and operate the railways when necessary in time of war or other like public necessity-I now very earnestly renew.

The necessity for such legislation is manifest and pressing. Those who have entrusted us with the responsibility and duty of serving and safeguarding them in such matters would find it hard, I believe, to excuse a failure to act upon these grave matters or any unnecessary postponement of action upon them.

Not only does the Interstate Commerce Commission now find it practically impossible, with its present membership and organization, to perform its great functions promptly and thoroughly, but it is not unlikely that it may presently be found advisable to add to its duties still others equally heavy and exacting. It must first be perfected as an administrative instrument.

The country cannot and should not consent to remain any longer exposed to profound industrial disturbances for lack of additional means of arbitration and conciliation which the Congress can easily and promptly supply.

And all will agree that there must be no doubt as to the power of the Executive to make immediate and uninterrupted use of the railroads for the concentration of the military forces of the nation wherever they are needed and whenever they are needed.

This is a program of regulation, prevention and administrative efficiency which argues its own case in the mere statement of it. With regard to one of its items, the increase in the efficiency of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the House of Representatives has already acted; its action needs only the concurrence of the Senate.

I would hesitate to recommend, and I dare say the Congress would hesitate to act upon the suggestion should I make it, that any man in any I occupation should be obliged by law to continue in an employment which he desired to leave.

To pass a law which forbade or prevented the individual workman to leave his work before receiving the approval of society in doing so would be to adopt a new principle into our jurisprudence, which I take it for granted we are not prepared to introduce.

But the proposal that the operation of the railways of the country shall not be stopped or interrupted by the concerted action of organized bodies of men until a public investigation shall have been instituted, which shall make the whole question at issue plain for the judgment of the opinion of the nation, is not to propose any such principle.

It is based upon the very different principle that the concerted action of powerful bodies of men shall not be permitted to stop the industrial processes of the nation, at any rate before the nation shall have had an opportunity to acquaint itself with the merits of the case as between employe and employer, time to form its opinion upon an impartial statement of the merits, and opportunity to consider all practicable means of conciliation or arbitration.

I can see nothing in that proposition but the justifiable safeguarding by society of the necessary processes of its very life. There is nothing arbitrary or unjust in it unless it be arbitrarily and unjustly done. It can and should be done with a full and scrupulous regard for the interests and liberties of all concerned as well as for the permanent interests of society itself.

Three matters of capital importance await the action of the Senate which have already been acted upon by the House of Representatives; the bill which seeks to extend greater freedom of combination to those engaged in promoting the foreign commerce of the country than is now thought by some to be legal under the terms of the laws against monopoly; the bill amending the present organic law of Porto Rico; and the bill proposing a more thorough and systematic regulation of the expenditure of money in elections, commonly called the Corrupt Practices Act.

I need not labor my advice that these measures be enacted into law. Their urgency lies in the manifest circumstances which render their adoption at this time not only opportune but necessary. Even delay would seriously jeopard the interests of the country and of the Government.

Immediate passage of the bill to regulate the expenditure of money in elections may seem to be less necessary than the immediate enactment of the other measures to which I refer, because at least two years will elapse before another election in which Federal offices are to be filled; but it would greatly relieve the public mind if this important matter were dealt with while the circumstances and the dangers to the public morals of the present method of obtaining and spending campaign funds stand clear under recent observation, and the methods of expenditure can be frankly studied in the light of present experience; and a delay would have the further very serious disadvantage of postponing action until another election was at hand and some special object connected with it might be thought to be in the mind of those who urged it. Action can be taken now with facts for guidance and without suspicion of partisan purpose.

I shall not argue at length the desirability of giving a freer hand in the matter of combined and concerted effort to those who shall undertake the essential enterprise of building up our export trade. That enterprise will presently, will immediately assume, has indeed already assumed a magnitude unprecedented in our experience. We have not the necessary instrumentalities for its prosecution; it is deemed to be doubtful whether they could be created upon an adequate scale under our present laws.

We should clear away all legal obstacles and create a basis of undoubted law for it which will give freedom without permitting unregulated license. The thing must be done now, because the opportunity is here and may escape us if we hesitate or delay.

The argument for the proposed amendments of the organic law of Porto Rico is brief and conclusive. The present laws governing the island and regulating the rights and privileges of its people are not just. We have created expectations of extended privilege which we have not satisfied. There is uneasiness among the people of the island and even a suspicious doubt with regard to our intentions concerning them which the adoption of the pending measure would happily remove. We do not doubt what we wish to do in any essential particular. We ought to do it at once.

At the last session of the Congress a bill was passed by the Senate which provides for the promotion of vocational and industrial education, which is of vital importance to the whole country because it concerns a matter, too long neglected, upon which the thorough industrial preparation of the country for the critical years of economic development immediately ahead of us in very large measure depends.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/spe...)

Wilson's 1916 Annual Message, Part Two

Wilson's 1916 Annual Message, Part TwoMay I not urge its early and favorable consideration by the House of Representatives and its early enactment into law? It contains plans which affect all interests and all parts of the country, and I am sure that there is no legislation now pending before the Congress whose passage the country awaits with more thoughtful approval or greater impatience to see a great and admirable thing set in the way of being done.

There are other matters already advanced to the stage of conference between the two houses of which it is not necessary that I should speak. Some practicable basis of agreement concerning them will no doubt be found an action taken upon them.

Inasmuch as this is, gentlemen , probably the last occasion I shall have to address the Sixty-fourth Congress, I hope that you will permit me to say with what genuine pleasure and satisfaction I have co-operated with you in the many measures of constructive policy with which you have enriched the legislative annals of the country. It has been a privilege to labor in such company. I take the liberty of congratulating you upon the completion of a record of rare serviceableness and distinction.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/spe...)

Wilson's 1916 Peace Note

Wilson's 1916 Peace NoteTo bring peace to the world and to avert the possibility of American participation, Wilson appealed to the belligerents on 18 December 1916 to disclose the terms upon which they would agree to end the fighting. The Germans refused to divulge their terms. The Allies—emboldened by Lansing's assurances, made secretly to the French and British ambassadors, that Wilson was pro-Ally—announced terms that could be achieved only by complete defeat of the Central Powers. Undaunted, Wilson opened secret negotiations with the German government. He was, he told Berlin, prepared to be an independent and impartial mediator, and he could force the Allies to the peace table because they were now totally dependent upon American credit and supplies. While he waited for a reply from Berlin, Wilson went before the Senate on 22 January 1917 to describe the kind of a peace settlement that the United States was prepared to work for and support. It had to be a "peace without victory," he said, one without indemnities and annexations. Above all, it had to be based upon a league of nations to preserve peace.

(Source: http://www.presidentprofiles.com/Gran...)

More:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2637713

(no image) Official Statements of War Aims and Peace Proposals: December 1916 to November 1918 by James Brown Scott (no photo)

Wilson's "A World League of Peace" Speech (January 22, 1917), Part One

Wilson's "A World League of Peace" Speech (January 22, 1917), Part OneGentlemen of the Senate:

On the eighteenth of December last I addressed an identic note to the governments of the nations now at war requesting them to state, more definitely than they had yet been stated by either group of belligerents, the terms upon which they would deem it possible to make peace. I spoke on behalf of humanity and of the rights of all neutral nations like our own, many of whose most vital interests the war puts in constant jeopardy.

The Central Powers united in a reply which stated merely that they were ready to meet their antagonists in conference to discuss terms of peace.

The Entente Powers have replied much more definitely and have stated, in general terms, indeed, but with sufficient definiteness to imply details, the arrangements, guarantees, and acts of reparation which they deem to be the indispensable conditions of a satisfactory settlement.

We are that much nearer a definite discussion of the peace which shall end the present war. We are that much nearer the discussion of the international concert which must thereafter hold the world at peace.

In every discussion of the peace that must end this war it is taken for granted that that peace must be followed by some definite concert of power which will make it virtually impossible that any such catastrophe should ever overwhelm us again. Every lover of mankind, every sane and thoughtful man must take that for granted.

I have sought this opportunity to address you because I thought that I owed it to you, as the council associated with me in the final determination of our international obligations, to disclose to you without reserve the thought and purpose that have been taking form in my mind in regard to the duty of our Government in the days to come when it will be necessary to lay afresh and upon a new plan the foundations of peace among the nations.

It is inconceivable that the people of the United States should play no part in that great enterprise. To take part in such a service will be the opportunity for which they have sought to prepare themselves by the very principles and purposes of their polity and the approved practices of their Government ever since the days when they set up a new nation in the high and honorable hope that it might in all that it was and did show mankind the way to liberty.

They cannot in honor withhold the service to which they are now about to be challenged. They do not wish to withhold it. But they owe it to themselves and to the other nations of the world to state the conditions under which they will feel free to render it. That service is nothing less than this, to add their authority and their power to the authority and force of other nations to guarantee peace and justice throughout the world. Such a settlement cannot now be long postponed. It is right that before it comes this Government should frankly formulate the conditions upon which it would feel justified in asking our people to approve its formal and solemn adherence to a League for Peace. I am here to attempt to state those conditions.

The present war must first be ended; but we owe it to candor and to a just regard for the opinion of mankind to say that, so far as our participation in guarantees of future peace is concerned, it makes a great deal of difference in what way and upon what terms it is ended. The treaties and agreements which bring it to an end must embody terms which will create a peace that is worth guaranteeing and preserving, a peace that will win the approval of mankind, not merely a peace that will serve the several interests and immediate aims of the nations engaged.

We shall have no voice in determining what those terms shall be, but we shall, I feel sure, have a voice in determining whether they shall be made lasting or not by the guarantees of a universal covenant; and our judgment upon what is fundamental and essential as a condition precedent to permanency should be spoken now, not afterwards when it may be too late.

No covenant of cooperative peace that does not include the peoples of the New World can suffice to keep the future safe against war; and yet there is only one sort of peace that the peoples of America could join in guaranteeing.

The elements of that peace must be elements that engage the confidence and satisfy the principles of the American governments, elements consistent with their political faith and with the practical convictions which the peoples of America have once for all embraced and undertaken to defend.

I do not mean to say that any American government would throw any obstacle in the way of any terms of peace the governments now at war might agree upon, or seek to upset them when made, whatever they might be. I only take it for granted that mere terms of peace between the belligerents will not satisfy even the belligerents themselves.

Mere agreements may not make peace secure. It will be absolutely necessary that a force be created as a guarantor of the permanency of the settlement so much greater than the force of any nation now engaged or any alliance hitherto formed or projected that no nation, no probable combination of nations could face or withstand it.

If the peace presently to be made is to endure, it must be a peace made secure by the organized major force of mankind.

The terms of the immediate peace agreed upon will determine whether it is a peace for which such a guarantee can be secured. The question upon which the whole future peace and policy of the world depends is this:

Is the present war a struggle for a just and secure peace, or only for a new balance of power? If it be only a struggle for a new balance of power, who will guarantee, who can guarantee, the stable equilibrium of the new arrangement?

Only a tranquil Europe can be a stable Europe. There must be, not a balance of power, but a community of power; not organized rivalries, but an organized common peace.

Fortunately we have received very explicit assurances on this point. The statesmen of both of the groups of nations now arrayed against one another have said, in terms that could not be misinterpreted, that it was no part of the purpose they had in mind to crush their antagonists. But the implications of these assurances may not be equally clear to all?may not be the same on both sides of the water. I think it will be serviceable if I attempt to set forth what we understand them to be.

They imply, first of all, that it must be a peace without victory. It is not pleasant to say this. I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought.

I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor's terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand.

Only a peace between equals can last. Only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit. The right state of mind, the right feeling between nations, is as necessary for a lasting peace as is the just settlement of vexed questions of territory or of racial and national allegiance.

The equality of nations upon which peace must be founded if it is to last must be an equality of rights; the guarantees exchanged must neither recognize nor imply a difference between big nations and small, between those that are powerful and those that are weak.

Right must be based upon the common strength, not upon the individual strength, of the nations upon whose concert peace will depend.

Equality of territory or of resources there of course cannot be; nor any other sort of equality not gained in the ordinary peaceful and legitimate development of the peoples themselves. But no one asks or expects anything more than an equality of rights. Mankind is looking now for freedom of life, not for equipoises of power.

And there is a deeper thing involved than even equality of right among organized nations. No peace can last, or ought to last, which does not recognize and accept the principle that governments derive all their just powers from the consent of the governed, and that no right anywhere exists to hand peoples about from sovereignty to sovereignty as if they were property.

I take it for granted, for instance, if I may venture upon a single example, that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, and autonomous Poland, and that henceforth inviolable security of life, of worship, and of industrial and social development should be guaranteed to all peoples who have lived hitherto under the power of governments devoted to a faith and purpose hostile to their own.

I speak of this, not because of any desire to exalt an abstract political principle which has always been held very dear by those who have sought to build up liberty in America, but for the same reason that I have spoken of the other conditions of peace which seem to me clearly indispensable,?because I wish frankly to uncover realities.

Any peace which does not recognize and accept this principle will inevitably be upset. It will not rest upon the affections or the convictions of mankind. The ferment of spirit of whole populations will fight subtly and constantly against it, and all the world will sympathize. The world can be at peace only if its life is stable, and there can be no stability where the will is in rebellion, where there is not tranquillity of spirit and a sense of justice, of freedom, and of right.

So far as practicable, moreover, every great people now struggling towards a full development of its resources and of its powers should be assured a direct outlet to the great highways of the sea. Where this cannot be done by the cession of territory, it can no doubt be done by the neutralization of direct rights of way under the general guarantee which will assure the peace itself. With a right comity of arrangement no nation need be shut away from free access to the open paths of the world's commerce.

And the paths of the sea must alike in law and in fact be free. The freedom of the seas is the sine qua non of peace, equality, and cooperation.

No doubt a somewhat radical reconsideration of many of the rules of international practice hitherto thought to be established may be necessary in order to make the seas indeed free and common in practically all circumstances for the use of mankind, but the motive for such changes is convincing and compelling. There can be no trust or intimacy between the peoples of the world without them.

The free, constant, unthreatened intercourse of nations is an essential part of the process of peace and of development. It need not be difficult either to define or to secure the freedom of the seas if the governments of the world sincerely desire to come to an agreement concerning it.

It is a problem closely connected with the limitation of naval armaments and the cooperation of the navies of the world in keeping the seas at once free and safe. And the question of limiting naval armaments opens the wider and perhaps more difficult question of the limitation of armies and of all programs of military preparation.

Difficult and delicate as these questions are, they must be faced with the utmost candor and decided in a spirit of real accommodation if peace is to come with healing in its wings, and come to stay. Peace cannot be had without concession and sacrifice. There can be no sense of safety and equality among the nations if great preponderating armaments are henceforth to continue here and there to be built up and maintained.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/spe...)

Wilson's "A World League of Peace" Speech (January 22, 1917), Part Two

Wilson's "A World League of Peace" Speech (January 22, 1917), Part TwoThe statesmen of the world must plan for peace and nations must adjust and accommodate their policy to it as they have planned for war and made ready for pitiless contest and rivalry. The question of armaments, whether on land or sea, is the most immediately and intensely practical question connected with the future fortunes of nations and of mankind.

I have spoken upon these great matters without reserve and with the utmost explicitness because it has seemed to me to be necessary if the world's yearning desire for peace was anywhere to find free voice and utterance. Perhaps I am the only person in high authority amongst all the peoples of the world who is at liberty to speak and hold nothing back.

I am speaking as an individual, and yet I am speaking also, of course, as the responsible head of a great government, and I feel confident that I have said what the people of the United States would wish me to say. May I not add that I hope and believe that I am in effect speaking for liberals and friends of humanity in every nation and of every program of liberty?

I would fain believe that I am speaking for the silent mass of mankind everywhere who have as yet had no place or opportunity to speak their real hearts out concerning the death and ruin they see to have come already upon the persons and the homes they hold most dear.

And in holding out the expectation that the people and Government of the United States will join the other civilized nations of the world in guaranteeing the permanence of peace upon such terms as I have named I speak with the greater boldness and confidence because it is clear to every man who can think that there is in this promise no breach in either our traditions or our policy as a nation, but a fulfilment, rather, of all that we have professed or striven for.

I am proposing, as it were, that the nations should with one accord adopt the doctrine of President Monroe as the doctrine of the world: that no nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people, but that every people should be left free to determine its own polity, its own way of development, unhindered, unthreatened, unafraid, the little along with the great and powerful.

I am proposing that all nations henceforth avoid entangling alliances which would draw them into competitions of power, catch them in a net of intrigue and selfish rivalry, and disturb their own affairs with influences intruded from without. There is no entangling alliance in a concert of power. When all unite to act in the same sense and with the same purpose all act in the common interest and are free to live their own lives under a common protection.

I am proposing government by the consent of the governed; that freedom of the seas which in international conference after conference representatives of the United States have urged with the eloquence of those who are the convinced disciples of liberty; and that moderation of armaments which makes of armies and navies a power for order merely, not an instrument of aggression or of selfish violence.

These are American principles, American policies. We could stand for no others. And they are also the principles and policies of forward looking men and women everywhere, of every modern nation, of every enlightened community. They are the principles of mankind and must prevail.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/spe...)

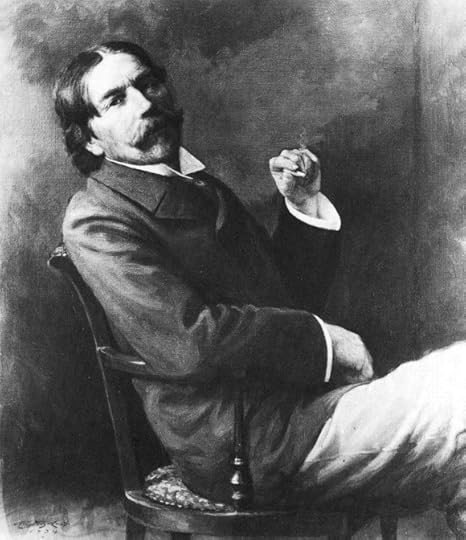

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

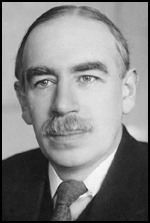

John Maynard Keynes was born on 5 June 1883 in Cambridge into a well-to-do academic family. His father was an economist and a philosopher, his mother became the town's first female mayor. He excelled academically at Eton as well as Cambridge University, where he studied mathematics. He also became friends with members of the Bloomsbury group of intellectuals and artists.

After graduating, Keynes went to work in the India Office, and simultaneously managed to work on a dissertation - often during office hours - which earned him a fellowship at King's College. In 1908, he quit the civil service and returned to Cambridge. Following the outbreak of World War One, Keynes joined the treasury, and in the wake of the Versailles peace treaty, he published 'The Economic Consequences of the Peace' in which he criticised the exorbitant war reparations demanded from a defeated Germany and prophetically predicted that it would foster a desire for revenge among Germans. This best-selling book made him world famous.

During the inter-war years, Keynes amassed a considerable personal fortune from the financial markets and, as bursar of King's College, greatly improved the college's financial position. He became a prominent arts patron and board member of a number of companies. In 1926, he married Lydia Lopokova, a Russian ballerina.

Keynes' best-known work, 'The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money', was published in 1936, and became a benchmark for future economic thought. It also secured his position as Britain's most influential economist, and with the advent of World War Two, he again worked for the treasury. In 1942, he was made a member of the house of lords.

During the war years, Keynes played a decisive role in the negotiations that were to shape the post-war international economic order. In 1944, he led the British delegation to the Bretton Woods conference in the United States. At the conference he played a significant part in the planning of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. He died on 21 April 1946.

(Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic...)

More:

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_May...

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bi...

http://economics.about.com/od/famouse...

by

by

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes by Dudley Dillard (no photo)

by Dudley Dillard (no photo)

by

by

Robert Skidelsky

Robert Skidelsky

Monroe Doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

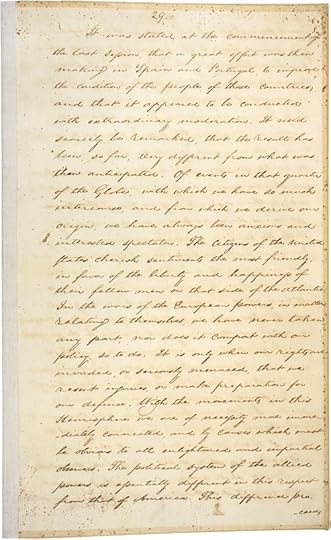

In his December 2, 1823, address to Congress, President James Monroe articulated United States' policy on the new political order developing in the rest of the Americas and the role of Europe in the Western Hemisphere.

The statement, known as the Monroe Doctrine, was little noted by the Great Powers of Europe, but eventually became a longstanding tenet of U.S. foreign policy. Monroe and his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams drew upon a foundation of American diplomatic ideals such as disentanglement from European affairs and defense of neutral rights as expressed in Washington's Farewell Address and Madison's stated rationale for waging the War of 1812. The three main concepts of the doctrine--separate spheres of influence for the Americas and Europe, non-colonization, and non-intervention--were designed to signify a clear break between the New World and the autocratic realm of Europe. Monroe's administration forewarned the imperial European powers against interfering in the affairs of the newly independent Latin American states or potential United States territories. While Americans generally objected to European colonies in the New World, they also desired to increase United States influence and trading ties throughout the region to their south. European mercantilism posed the greatest obstacle to economic expansion. In particular, Americans feared that Spain and France might reassert colonialism over the Latin American peoples who had just overthrown European rule. Signs that Russia was expanding its presence southward from Alaska toward the Oregon Territory were also disconcerting.

For their part, the British also had a strong interest in ensuring the demise of Spanish colonialism, with all the trade restrictions mercantilism imposed. Earlier in 1823 British Foreign Minister George Canning suggested to Americans that two nations issue a joint declaration to deter any other power from intervening in Central and South America. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, however, vigorously opposed cooperation with Great Britain, contending that a statement of bilateral nature could limit United States expansion in the future. He also argued that the British were not committed to recognizing the Latin American republics and must have had imperial motivations themselves.

(Source: http://history.state.gov/milestones/1...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monroe_D...

http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/our...

http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?f...

http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org/life...

by Jay Sexton (no photo)

by Jay Sexton (no photo) by Gaddis Smith (no photo)

by Gaddis Smith (no photo) by Edward J. Renehan Jr. (no photo)

by Edward J. Renehan Jr. (no photo) by Armin Rappaport (no photo)

by Armin Rappaport (no photo)(no image)The Monroe Doctrine: Its Modern Significance by Donald Marquand Dozer (no photo)

Zimmermann Telegram

Zimmermann Telegram

FROM 2nd from London # 5747.

“We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal or alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.”

Signed, ZIMMERMANN.

(Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4938/)

More:

http://www.archives.gov/education/les...

http://www.nsa.gov/public_info//_file...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zimmerm...

by

by

Barbara W. Tuchman

Barbara W. Tuchman by Thomas Boghardt (no photo)

by Thomas Boghardt (no photo) by William Friedman (no photo)

by William Friedman (no photo)

Wilson's February 3, 1917 Speech

Wilson's February 3, 1917 SpeechGentlemen of the Congress:

The Imperial German Government on the thirty-first of January announced to this Government and to the governments of the other neutral nations that on and after the first day of February, the present month, it would adopt a policy with regard to the use of submarines against all shipping seeking to pass through certain designated areas of the high seas to which it is clearly my duty to call your attention.

Let me remind the Congress that on the eighteenth of April last, in view of the sinking on the twenty-fourth of March of the cross-Channel passenger steamer Sussex by a German submarine, without summons or warning, and the consequent loss of the lives of several citizens of the United States who were passengers aboard her, this Government addressed a note to the Imperial German Government in which it made the following declaration:

"If it is still the purpose of the Imperial Government to prosecute relentless and indiscriminate warfare against vessels of commerce by the use of submarines without regard to what the Government of the United States must consider the sacred and indisputable rules of international law and the universally recognized dictates of humanity, the Government of the United States is at last forced to the conclusion that there is but one course it can pursue. Unless the Imperial Government should now immediately declare and effect an abandonment of its present methods of submarine warfare against passenger and freight-carrying vessels, the Government of the United States can have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the German Empire altogether."

In reply to this declaration the Imperial German Government gave this Government the following assurance:

"The German Government is prepared to do its utmost to confine the operations of war for the rest of its duration to the fighting forces of the belligerents, thereby also insuring the freedom of the seas, a principle upon which the German Government believes, now as before, to be in agreement with the Government of the United States.

"The German Government, guided by this idea, notifies the Government of the United States that the German naval forces have received the following orders:

In accordance with the general principles of visit and search and destruction of merchant vessels recognized by international law, such vessels, both within and without the area declared as naval war zone, shall not be sunk without warning and without saving human lives, unless these ships attempt to escape or offer resistance.

"But," it added, "neutrals cannot expect that Germany, forced to fight for her existence, shall, for the sake of neutral interest, restrict the use of an effective weapon if her enemy is permitted to continue to apply at will methods of warfare violating the rules of international law. Such a demand would be incompatible with the character of neutrality, and the German Government is convinced that the Government of the United States does not think of making such a demand, knowing that the Government of the United States has repeatedly declared that it is determined to restore the principle of the freedom of the seas, from whatever quarter it has been violated."

To this the Government of the United States replied on the eighth of May, accepting, of course, the assurances given, but adding,

"The Government of the United States feels it necessary to state that it takes it for granted that the Imperial German Government does not intend to imply that the maintenance of its newly announced policy is in any way contingent upon the course or result of diplomatic negotiations between the Government of the United States and any other belligerent Government, notwithstanding the fact that certain passages in the Imperial Government's note of the fourth instant might appear to be susceptible of that construction. In order, however, to avoid any possible misunderstanding, the Government of the United States notifies the Imperial Government that it cannot for a moment entertain, much less discuss, a suggestion that respect by German naval authorities for the rights of citizens of the United States upon the high seas should in any way or in the slightest degree be made contingent upon the conduct of any other Government affecting the rights of neutrals and non-combatants. Responsibility in such matters is single, not joint; absolute, not relative."

To this note of the eighth of May the Imperial German Government made no reply.

On the thirty-first of January, the Wednesday of the present week, the German Ambassador handed to the Secretary of State, along with a formal note, a memorandum which contains the following statement:

"The Imperial Government, therefore, does not doubt that the Government of the United States will understand the situation thus forced upon Germany by the Entente-Allies' brutal methods of war and by their determination to destroy the Central Powers, and that the Government of the United States will further realize that the now openly disclosed intentions of the Entente-Allies give back to Germany the freedom of action which she reserved in her note addressed to the Government of the United States on May 4, 1916.

"Under these circumstances Germany will meet the illegal measures of her enemies by forcibly preventing after February 1, 1917, in a zone around Great Britain, France, Italy, and in the Eastern Mediterranean all navigation, that of neutrals included, from and to England and from and to France, etc., etc. All ships met within the zone will be sunk."

I think that you will agree with me that, in view of this declaration, which suddenly and without prior intimation of any kind deliberately withdraws the solemn assurance given in the Imperial Government's note of the fourth of May, 1916, this Government has no alternative consistent with the dignity and honor of the United States but to take the course which, in its note of the eighteenth of April, 1916, it announced that it would take in the event that the German Government did not declare and effect an abandonment of the methods of submarine warfare which it was then employing and to which it now purposes again to resort.

I have, therefore, directed the Secretary of State to announce to His Excellency the German Ambassador that all diplomatic relations between the United States and the German Empire are severed, and that the American Ambassador at Berlin will immediately be withdrawn; and, in accordance with this decision, to hand to His Excellency his passports.

Notwithstanding this unexpected action of the German Government, this sudden and deeply deplorable renunciation of its assurances, given this Government at one of the most critical moments of tension in the relations of the two governments, I refuse to believe that it is the intention of the German authorities to do in fact what they have warned us they will feel at liberty to do. I cannot bring myself to believe that they will indeed pay no regard to the ancient friendship between their people and our own or to the solemn obligations which have been exchanged between them and destroy American ships and take the lives of American citizens in the willful prosecution of the ruthless naval program they have announced their intention to adopt.

Only actual overt acts on their part can make me believe it even now.

If this inveterate confidence on my part in the sobriety and prudent foresight of their purpose should unhappily prove unfounded; if American ships and American lives should in fact be sacrificed by their naval commanders in heedless contravention of the just and reasonable understandings of international law and the obvious dictates of humanity, I shall take the liberty of coming again before the Congress, to ask that authority be given me to use any means that may be necessary for the protection of our seamen and our people in the prosecution of their peaceful and legitimate errands on the high seas. I can do nothing less. I take it for granted that all neutral governments will take the same course.

We do not desire any hostile conflict with the Imperial German Government. We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with the Government which speaks for them. We shall not believe that they are hostile to us unless and until we are obliged to believe it; and we purpose nothing more than the reasonable defense of the undoubted rights of our people. We wish to serve no selfish ends. We seek merely to stand true alike in thought and in action to the immemorial principles of our people which I sought to express in my address to the Senate only two weeks ago,—seek merely to vindicate our right to liberty and justice and an unmolested life. These are the bases of peace, not war. God grant we may not be challenged to defend them by acts of wilful injustice on the part of the Government of Germany!

(Source: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/ind...)

Wilson's Second Inaugural Address

Wilson's Second Inaugural AddressMy Fellow Citizens:

The four years which have elapsed since last I stood in this place have been crowded with counsel and action of the most vital interest and consequence. Perhaps no equal period in our history has been so fruitful of important reforms in our economic and industrial life or so full of significant changes in the spirit and purpose of our political action. We have sought very thoughtfully to set our house in order, correct the grosser errors and abuses of our industrial life, liberate and quicken the processes of our national genius and energy, and lift our politics to a broader view of the people's essential interests.

It is a record of singular variety and singular distinction. But I shall not attempt to review it. It speaks for itself and will be of increasing influence as the years go by. This is not the time for retrospect. It is time rather to speak our thoughts and purposes concerning the present and the immediate future.

Although we have centered counsel and action with such unusual concentration and success upon the great problems of domestic legislation to which we addressed ourselves four years ago, other matters have more and more forced themselves upon our attention-- matters lying outside our own life as a nation and over which we had no control, but which, despite our wish to keep free of them, have drawn us more and more irresistibly into their own current and influence.

It has been impossible to avoid them. They have affected the life of the whole world. They have shaken men everywhere with a passion and an apprehension they never knew before. It has been hard to preserve calm counsel while the thought of our own people swayed this way and that under their influence. We are a composite and cosmopolitan people. We are of the blood of all the nations that are at war. The currents of our thoughts as well as the currents of our trade run quick at all seasons back and forth between us and them. The war inevitably set its mark from the first alike upon our minds, our industries, our commerce, our politics and our social action. To be indifferent to it, or independent of it, was out of the question.

And yet all the while we have been conscious that we were not part of it. In that consciousness, despite many divisions, we have drawn closer together. We have been deeply wronged upon the seas, but we have not wished to wrong or injure in return; have retained throughout the consciousness of standing in some sort apart, intent upon an interest that transcended the immediate issues of the war itself.

As some of the injuries done us have become intolerable we have still been clear that we wished nothing for ourselves that we were not ready to demand for all mankind--fair dealing, justice, the freedom to live and to be at ease against organized wrong.

It is in this spirit and with this thought that we have grown more and more aware, more and more certain that the part we wished to play was the part of those who mean to vindicate and fortify peace. We have been obliged to arm ourselves to make good our claim to a certain minimum of right and of freedom of action. We stand firm in armed neutrality since it seems that in no other way we can demonstrate what it is we insist upon and cannot forget. We may even be drawn on, by circumstances, not by our own purpose or desire, to a more active assertion of our rights as we see them and a more immediate association with the great struggle itself. But nothing will alter our thought or our purpose. They are too clear to be obscured. They are too deeply rooted in the principles of our national life to be altered. We desire neither conquest nor advantage. We wish nothing that can be had only at the cost of another people. We always professed unselfish purpose and we covet the opportunity to prove our professions are sincere.

There are many things still to be done at home, to clarify our own politics and add new vitality to the industrial processes of our own life, and we shall do them as time and opportunity serve, but we realize that the greatest things that remain to be done must be done with the whole world for stage and in cooperation with the wide and universal forces of mankind, and we are making our spirits ready for those things.

We are provincials no longer. The tragic events of the thirty months of vital turmoil through which we have just passed have made us citizens of the world. There can be no turning back. Our own fortunes as a nation are involved whether we would have it so or not.

And yet we are not the less Americans on that account. We shall be the more American if we but remain true to the principles in which we have been bred. They are not the principles of a province or of a single continent. We have known and boasted all along that they were the principles of a liberated mankind. These, therefore, are the things we shall stand for, whether in war or in peace:

That all nations are equally interested in the peace of the world and in the political stability of free peoples, and equally responsible for their maintenance; that the essential principle of peace is the actual equality of nations in all matters of right or privilege; that peace cannot securely or justly rest upon an armed balance of power; that governments derive all their just powers from the consent of the governed and that no other powers should be supported by the common thought, purpose or power of the family of nations; that the seas should be equally free and safe for the use of all peoples, under rules set up by common agreement and consent, and that, so far as practicable, they should be accessible to all upon equal terms; that national armaments shall be limited to the necessities of national order and domestic safety; that the community of interest and of power upon which peace must henceforth depend imposes upon each nation the duty of seeing to it that all influences proceeding from its own citizens meant to encourage or assist revolution in other states should be sternly and effectually suppressed and prevented.

I need not argue these principles to you, my fellow countrymen; they are your own part and parcel of your own thinking and your own motives in affairs. They spring up native amongst us. Upon this as a platform of purpose and of action we can stand together. And it is imperative that we should stand together. We are being forged into a new unity amidst the fires that now blaze throughout the world. In their ardent heat we shall, in God's Providence, let us hope, be purged of faction and division, purified of the errant humors of party and of private interest, and shall stand forth in the days to come with a new dignity of national pride and spirit. Let each man see to it that the dedication is in his own heart, the high purpose of the nation in his own mind, ruler of his own will and desire.

I stand here and have taken the high and solemn oath to which you have been audience because the people of the United States have chosen me for this august delegation of power and have by their gracious judgment named me their leader in affairs.

I know now what the task means. I realize to the full the responsibility which it involves. I pray God I may be given the wisdom and the prudence to do my duty in the true spirit of this great people. I am their servant and can succeed only as they sustain and guide me by their confidence and their counsel. The thing I shall count upon, the thing without which neither counsel nor action will avail, is the unity of America--an America united in feeling, in purpose and in its vision of duty, of opportunity and of service.

We are to beware of all men who would turn the tasks and the necessities of the nation to their own private profit or use them for the building up of private power.

United alike in the conception of our duty and in the high resolve to perform it in the face of all men, let us dedicate ourselves to the great task to which we must now set our hand. For myself I beg your tolerance, your countenance and your united aid.

The shadows that now lie dark upon our path will soon be dispelled, and we shall walk with the light all about us if we be but true to ourselves--to ourselves as we have wished to be known in the counsels of the world and in the thought of all those who love liberty and justice and the right exalted.

(Source: http://millercenter.org/president/spe...)

Russian Revolution (February 1917)

Russian Revolution (February 1917)

In September 1915, Nicholas II assumed supreme command of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. This linked him to the country's military failures and during 1917 there was a strong decline support for his government.

The country's incompetent and corrupt system could not supply the necessary equipment to enable the Russian Army to fight a modern war. By 1917 over 1,300,000 men had been killed in battle, 4,200,000 wounded and 2,417,000 had been captured by the enemy.

In January 1917, General Krimov, returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma. Krimov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife Alexandra Fyodorovna was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics".

The First World War had a disastrous impact on the Russian econimy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. By January 1917 the price of commodities in Petrograd had increased six-fold. In an attempt to increase their wages, industrial workers went on strike and in Petrograd people took to the street demanding food. On 11th February, 1917, a large crowd marched through the streets of Petrograd breaking shop windows and shouting anti-war slogans.

The situation deteoriated on 22nd February when the owners of the Putilov Iron Works locked out its workforce after they demanded higher wages. Led by Bolshevik agitators, the 20,000 workers took to the streets. The army was ordered to disperse the demonstrations but they were unwilling to do this and in some cases the soldiers joined the protestors in demanding an end to the war.

Other workers joined the demonstrations and by 27th February an estimated 200,000 workers were on strike. Nicholas II, who was at Army Headquarters in Mogilev, ordered the commander of the Petrograd garrison to suppress "all the disorders on the streets of the capital". The following day troops fired on demonstrators in different parts of the city. Others refused to obey the order and the Pavlovsk regiment mutinied. Others regiments followed and soldiers joined the striking workers in the streets.

On 26th February Nicholas II ordered the Duma to close down. Members refused and they continued to meet and discuss what they should do. Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma, sent a telegram to the Tsar suggesting that he appoint a new government led by someone who had the confidence of the people. When the Tsar did not reply, the Duma nominated a Provisional Government headed by Prince George Lvov.

The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 28th February suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and on the 1st March, 1917, the Tsar abdicated leaving the Provisional Government in control of the country.

(Source: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/February...

http://www.marxists.org/archive/trots...

http://history1900s.about.com/od/Russ...

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...

http://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/201...

by Richard Pipes (no photo)

by Richard Pipes (no photo) by

by

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Sheila Fitzpatrick by

by

Robert Service

Robert Service by Rex A. Wade (no photo)

by Rex A. Wade (no photo) by

by

Orlando Figes

Orlando Figes(no image) The Russian Provisional Government 1917: Documents by Robert P. Browder (no photo)

Cloture Rule

Cloture RuleWoodrow Wilson considered himself an expert on Congress—the subject of his 1884 doctoral dissertation. When he became president in 1913, he announced his plans to be a legislator-in-chief and requested that the President’s Room in the Capitol be made ready for his weekly consultations with committee chairmen. For a few months, Wilson kept to that plan. Soon, however, traditional legislative-executive branch antagonisms began to tarnish his optimism. After passing major tariff, trade, and banking legislation in the first two years of his administration, Congress slowed its pace.

By 1915, the Senate had become a breeding ground for filibusters. In the final weeks of the Congress that ended on March 4, one administration measure related to the war in Europe tied the Senate up for 33 days and blocked passage of three major appropriations bills. Two years later, as pressure increased for American entry into that war, a 23-day, end-of-session filibuster against the president’s proposal to arm merchant ships also failed, taking with it much other essential legislation. For the previous 40 years, efforts in the Senate to pass a debate-limiting rule had come to nothing. Now, in the wartime crisis environment, President Wilson lost his patience.

Decades earlier, he had written in his doctoral dissertation, “It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and to talk much about what it sees.” On March 4, 1917, as the 64th Congress expired without completing its work, Wilson held a decidedly different view. Calling the situation unparalleled, he stormed that the “Senate of the United States is the only legislative body in the world which cannot act when its majority is ready for action. A little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own, have rendered the great government of the United States helpless and contemptible.” The Senate, he demanded, must adopt a cloture rule.

On March 8, 1917, in a specially called session of the 65th Congress, the Senate agreed to a rule that essentially preserved its tradition of unlimited debate. The rule required a two-thirds majority to end debate and permitted each member to speak for an additional hour after that before voting on final passage. Over the next 46 years, the Senate managed to invoke cloture on only five occasions.

(Source: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/h...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloture

http://www.senate.gov/reference/gloss...

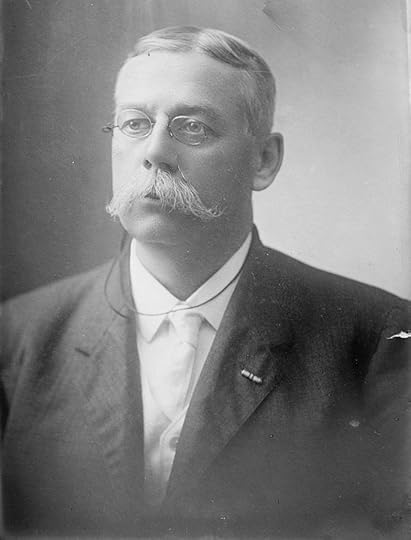

Frank I. Cobb

Frank I. CobbFrank I. Cobb was an American journalist. He succeeded Joseph Pulitzer as editor of The New York World, owned by Joseph Pulitzer. Cobb became famous for his editorials in support of the policies of liberal Democrats such as Woodrow Wilson.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_I....)

More:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3...

by Alan Axelrod (no photo)

by Alan Axelrod (no photo)

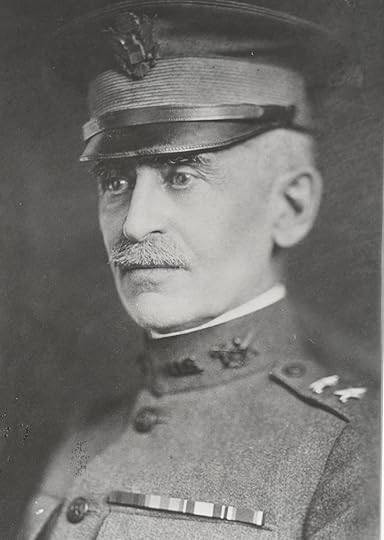

Admiral William Sims

Admiral William Sims

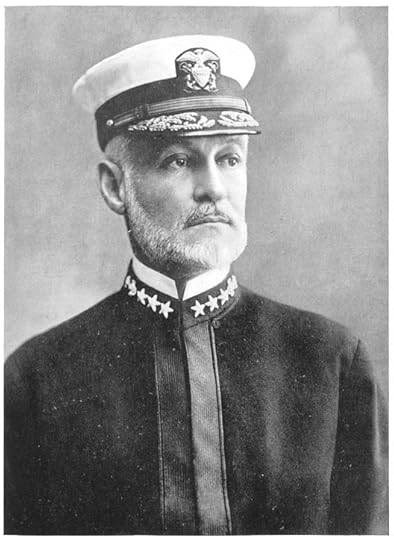

William S. Sims, born in 1858 in Ontario, Canada, was appointed to the Naval Academy in 1876 and graduated in 1880. Seventeen years of sea duty were followed by assignments as Naval Attaché to Paris, St. Petersburg, and Madrid. Sims next served as Inspector of Target Practice; and, under his supervision, the naval gunnery system increased the rapidity of hits 100 percent and the general effectiveness of fire 500 percent. He also served as Naval Aide to President Theodore Roosevelt for two and one-half years.

On 11 February 1917, Sims became President of the Naval War College. In March 1917, he was designated by the Secretary of the Navy as Representative of the Navy Department in London. With the entry of the United States into World War I in April, he was ordered to assume command of all American destroyers, tenders, and auxiliaries operating from British bases. In May, he was designated as Commander of United States Destroyers Operating from British Bases, with the rank of Vice Admiral; and, in June, his title was changed to Commander, United States Naval Forces Operating in European Waters. On 10 December 1917, he assumed additional duty as Naval Attaché, London, England. The North Sea Mine Barrage was laid under his direction.

Admiral Sims again became President of the Naval War College in April 1919 and served in that capacity until his retirement on 15 October 1922. He died at Boston, Mass., on 25 September 1936.

(Source: http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/s13...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_...

http://www.usnwc.edu/NWCSite/images/a...

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg....

by Ballard C. Campbell (no photo)

by Ballard C. Campbell (no photo)

Wilson's Declaration of War, Part One

Wilson's Declaration of War, Part OneGentlemen of the Congress:

I have called the Congress into extraordinary session because there are serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately, which it was neither right nor constitutionally permissible that I should assume the responsibility of making.

On the 3d of February last I officially laid before you the extraordinary announcement of the Imperial German Government that on and after the 1st day of February it was its purpose to put aside all restraints of law or of humanity and use its submarines to sink every vessel that sought to approach either the ports of Great Britain and Ireland or the western coasts of Europe or any of the ports controlled by the enemies of Germany within the Mediterranean. That had seemed to be the object of the German submarine warfare earlier in the war, but since April of last year the Imperial Government had somewhat restrained the commanders of its undersea craft in conformity with its promise then given to us that passenger boats should not be sunk and that due warning would be given to all other vessels which its submarines might seek to destroy, when no resistance was offered or escape attempted, and care taken that their crews were given at least a fair chance to save their lives in their open boats. The precautions taken were meagre and haphazard enough, as was proved in distressing instance after instance in the progress of the cruel and unmanly business, but a certain degree of restraint was observed The new policy has swept every restriction aside. Vessels of every kind, whatever their flag, their character, their cargo, their destination, their errand, have been ruthlessly sent to the bottom without warning and without thought of help or mercy for those on board, the vessels of friendly neutrals along with those of belligerents. Even hospital ships and ships carrying relief to the sorely bereaved and stricken people of Belgium, though the latter were provided with safe-conduct through the proscribed areas by the German Government itself and were distinguished by unmistakable marks of identity, have been sunk with the same reckless lack of compassion or of principle.

I was for a little while unable to believe that such things would in fact be done by any government that had hitherto subscribed to the humane practices of civilized nations. International law had its origin in the at tempt to set up some law which would be respected and observed upon the seas, where no nation had right of dominion and where lay the free highways of the world. By painful stage after stage has that law been built up, with meagre enough results, indeed, after all was accomplished that could be accomplished, but always with a clear view, at least, of what the heart and conscience of mankind demanded. This minimum of right the German Government has swept aside under the plea of retaliation and necessity and because it had no weapons which it could use at sea except these which it is impossible to employ as it is employing them without throwing to the winds all scruples of humanity or of respect for the understandings that were supposed to underlie the intercourse of the world. I am not now thinking of the loss of property involved, immense and serious as that is, but only of the wanton and wholesale destruction of the lives of noncombatants, men, women, and children, engaged in pursuits which have always, even in the darkest periods of modern history, been deemed innocent and legitimate. Property can be paid for; the lives of peaceful and innocent people can not be. The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.

It is a war against all nations. American ships have been sunk, American lives taken, in ways which it has stirred us very deeply to learn of, but the ships and people of other neutral and friendly nations have been sunk and overwhelmed in the waters in the same way. There has been no discrimination. The challenge is to all mankind. Each nation must decide for itself how it will meet it. The choice we make for ourselves must be made with a moderation of counsel and a temperateness of judgment befitting our character and our motives as a nation. We must put excited feeling away. Our motive will not be revenge or the victorious assertion of the physical might of the nation, but only the vindication of right, of human right, of which we are only a single champion.

When I addressed the Congress on the 26th of February last, I thought that it would suffice to assert our neutral rights with arms, our right to use the seas against unlawful interference, our right to keep our people safe against unlawful violence. But armed neutrality, it now appears, is impracticable. Because submarines are in effect outlaws when used as the German submarines have been used against merchant shipping, it is impossible to defend ships against their attacks as the law of nations has assumed that merchantmen would defend themselves against privateers or cruisers, visible craft giving chase upon the open sea. It is common prudence in such circumstances, grim necessity indeed, to endeavour to destroy them before they have shown their own intention. They must be dealt with upon sight, if dealt with at all. The German Government denies the right of neutrals to use arms at all within the areas of the sea which it has proscribed, even in the defense of rights which no modern publicist has ever before questioned their right to defend. The intimation is conveyed that the armed guards which we have placed on our merchant ships will be treated as beyond the pale of law and subject to be dealt with as pirates would be. Armed neutrality is ineffectual enough at best; in such circumstances and in the face of such pretensions it is worse than ineffectual; it is likely only to produce what it was meant to prevent; it is practically certain to draw us into the war without either the rights or the effectiveness of belligerents. There is one choice we can not make, we are incapable of making: we will not choose the path of submission and suffer the most sacred rights of our nation and our people to be ignored or violated. The wrongs against which we now array ourselves are no common wrongs; they cut to the very roots of human life.

With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking and of the grave responsibilities which it involves, but in unhesitating obedience to what I deem my constitutional duty, I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the Imperial German Government to be in fact nothing less than war against the Government and people of the United States; that it formally accept the status of belligerent which has thus been thrust upon it, and that it take immediate steps not only to put the country in a more thorough state of defense but also to exert all its power and employ all its resources to bring the Government of the German Empire to terms and end the war.