The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Woodrow Wilson

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

WOODROW WILSON: A BIOGRAPHY - GLOSSARY (SPOILER THREAD)

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk brought about the end of the war between Russia and Germany in 1918. The German were reminded of the harshness of Brest-Litovsk when they complained about the severity of the Treaty of Versailles signed in June 1919.

Lenin had ordered that the Bolshevik representatives should get a quick treaty from the Germans to bring about an end to the war so that the Bolsheviks could concentrate on the work they needed to do in Russia itself.

The start of the discussions was an organisational disaster. Representatives from the Allies, who were meant to have attended, failed to show. Russia, therefore, had to negotiate a peace settlement by herself.

After just one week of talks, the Russian delegation left so that it could report to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. It was at this meeting that it became clear that there were three views about the peace talks held within the Bolshevik hierarchy.

Trotsky believed that Germany would offer wholly unacceptable terms to the Russians and that this would spur the German workers to rise up in revolt against their leaders and in support of their Russian compatriots. This rebellion would, in turn, spark off a world-wide workers rebellion.

Kamenev believed that the German workers would rise up even if the terms of the treaty were reasonable.

Lenin believed that a world revolution would occur over many years. What Russia needed now was an end to the war with Germany and he wanted peace, effectively at any cost.

On January 21st, 1918, the Bolshevik hierarchy met. Only 15 out of 63 supported Lenin’s viewpoint. 16 voted for Trotsky who wanted to wage a “holy war” against all militarist nations, including Germany. 32 voted in favour of a revolutionary war against the Germans, which would, they believed, precipitate a workers rebellion in Germany.

The whole issue went to the party’s Central Committee. This body rejected the idea of a revolutionary war and supported an idea of Trotsky. He decided that he would offer the Germans Russia’s demobilisation and an end to the war but would not conclude a peace treaty with them. By doing this he hoped to buy time. In fact he got the opposite.

On February 18th, 1918, the Germans, tired of the Bolshevik’s procrastination, re-started their advance into Russia and advanced 100 miles in just four days. This re-confirmed in Lenin’s mind that a treaty was needed very quickly. Trotsky, having dropped the idea of the workers of Germany coming to the aid of Russia, followed Lenin. Lenin had managed to sell his idea to a small majority in the party’s hierarchy, though there were many who were still opposed to peace at any price with the Germans. However, it was Lenin who read the situation better than anyone else.

The Bolsheviks had relied on the support of the lowly Russian soldier in 1917. Lenin had promised an end to the war. Now the party had to deliver or face the consequences. On March 3rd, 1918, the treaty was signed.

Under the treaty, Russia lost Riga, Lithuania, Livonia, Estonia and some of White Russia. These areas had great economic importance as they were some of the most fertile farming areas in Western Russia. Germany was allowed by the terms of the treaty to exploit these lands to support her military effort in the west.

Lenin argued that though the treaty was harsh, it freed the Bolsheviks up to deal with problems in Russia itself. Only those on the extreme left of the party disagreed and were still of the belief that the workers of Germany would rise up in support of them. By March 1918, this clearly was not going to be the case. Lenin’s pragmatic and realistic approach enabled him to strengthen his hold on the party even more and side-line the extreme left still further.

(Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_o...

http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmv...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/m...

http://www.marxists.org/archive/trots...

by

by

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky by John Wheeler-Bennett

by John Wheeler-Bennett by Yuri Felshtinsky (no photo)

by Yuri Felshtinsky (no photo) by

by

George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan

Russian Revolution (October 1917)

Russian Revolution (October 1917)

On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. Kerensky was still the most popular man in the government because of his political past. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. However, Kerensky, like George Lvov, was unwilling to end the war. In fact, soon after taking office, he announced a new summer offensive.

Soldiers on the Eastern Front were dismayed at the news and regiments began to refuse to move to the front line. There was a rapid increase in the number of men deserting and by the autumn of 1917 an estimated 2 million men had unofficially left the army.

Some of these soldiers returned to their homes and used their weapons to seize land from the nobility. Manor houses were burnt down and in some cases wealthy landowners were murdered. Kerensky and the Provisional Government issued warnings but were powerless to stop the redistribution of land in the countryside.

On 19th July, Kerensky gave orders for the arrest of leading Bolsheviks who were campaigning against the war. This included Vladimir Lenin, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, and Alexandra Kollontai. The Bolshevik headquarters at the Kshesinsky Palace, was also occupied by government troops.

After the failure of the July Offensive on the Eastern Front, Kerensky replaced General Alexei Brusilov with General Lavr Kornilov, as Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. The two men soon clashed about military policy. Kornilov wanted Kerensky to restore the death-penalty for soldiers and to militarize the factories. Kerensky refused and sacked Kornilov.

Kornilov responded by sending troops under the leadership of General Krymov to take control of Petrograd. Kerensky was now in danger and was forced to ask the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but in a speech made by their leader, Vladimir Lenin, he made clear they would be fighting against Kornilov rather than for Kerensky.

Within a few days Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided not to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody.

Lenin now returned to Petrograd but remained in hiding. On 25th September, Kerensky attempted to recover his left-wing support by forming a new coalition that included more Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. However, with the Bolsheviks controlling the Soviets and now able to call on 25,000 armed militia, Kerensky's authority had been undermined.

The Bolsheviks set up their headquarters in the Smolny Institute. The former girls' convent school also housed the Petrograd Soviet. Under pressure from the nobility and industrialists, Alexander Kerensky was persuaded to take decisive action. On 22nd October he ordered the arrest of the Military Revolutionary Committee. The next day he closed down the Bolshevik newspapers and cut off the telephones to the Smolny Institute.

Leon Trotsky now urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. Lenin agreed and on the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks began to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city.

The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace and arrested the Cabinet ministers.

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Vladimir Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Felix Dzerzhinsky (Internal Affairs), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War).

(Source: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_...

http://www.marxists.org/archive/trots...

http://history1900s.about.com/od/Russ...

http://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/higher/...

http://www.historytoday.com/edward-ac...

by Richard Pipes (no photo)

by Richard Pipes (no photo) by

by

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Sheila Fitzpatrick by

by

Robert Service

Robert Service by Rex A. Wade (no photo)

by Rex A. Wade (no photo) by

by

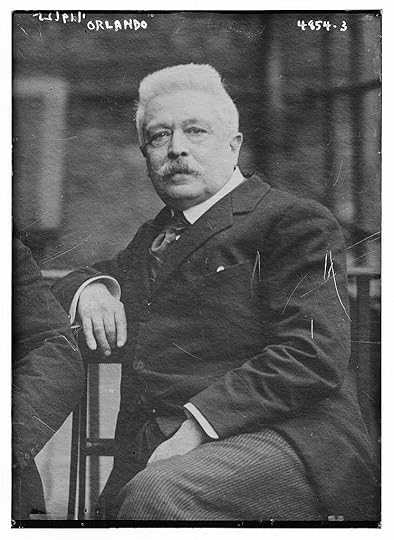

Orlando Figes

Orlando Figes by Philip Pomper (no photo)

by Philip Pomper (no photo)

French Army Mutinies

French Army Mutinies

In the first two months of the war, the French lost 329,000 soldiers. By Christmas 1914, almost a half million French soldiers had died. By December 1916, 3 million Frenchmen had been killed or wounded.

Early in 1917, a new French Army commander-in-chief, General Robert Nivelle, planned a major offensive on the German lines. His strategy was to soften the German defenses with artillery and then, with the aid of tanks, hurl large numbers of troops at the enemy. Nivelle predicted that a "break-through" would occur within 48 hours. This would then lead to a crushing defeat of the German Army and an end to the war.

More than a million French soldiers left their trenches to attack across no-man's land on April 16. But things went wrong. The artillery failed to blow openings in the German barbed-wire defenses. Well-protected German machine guns cut down thousands of Frenchmen in deadly crossfires. Many French tanks were blown up or got mired in the mud. Hard-driving rain further slowed the French advance.

After a week of French attacks, the German lines still held. More than 100,000 French soldiers had been killed or wounded. Incredibly, General Nivelle insisted on continuing his offensive, believing that the big "break-through" would come at any time.

The 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment had taken part in this offensive, and German machine gun fire had devastated it. Of the 600 men in the battalion, only 200 lived through the assault. Dazed and demoralized, the 2nd Battalion survivors were promised a period of rest behind the front. Instead, replacements filled the ranks of the dead and wounded, and on April 29 the battalion was again ordered to the front.

Angry and unbelieving, the men refused. Many of them, drunk on cheap wine, shouted, "Down with the war!" By midnight, the soldiers had sobered up and regained their military discipline. By 2 a.m., they reluctantly began to march to the trenches on the French front lines. Recognizing that a brief mutiny had occurred, officers decided that an example had to made of some of the mutineers. In the dark, about a dozen members of the battalion were pulled, more or less at random, from the ranks. They were court-martialed for leading the mutiny. Only those clearly innocent escaped punishment. One soldier, for example, proved he was in the hospital at the time of the mutiny. He was replaced with another man from the battalion. Most were sentenced to prisons outside the country. Five were sentenced to be shot. (One escaped into the woods when German shells exploded as he was being led to the firing squad. He was never found.)

Another, far larger mutiny broke out on May 3. When called to assemble in their battalions and regiments, almost the entire battle-weary 2nd Division came drunk and without their weapons. "We're not marching!" the soldiers shouted. They refused to move out to the trenches. The officers retreated to headquarters, unsure of what to do.

Throughout history, armies traditionally have put down mutinies with force. They overpower rebelling troops and execute them. But this was an entire division. The officers would have difficulty getting sufficient troops to overpower a division. And when they did overpower the division, they couldn't shoot thousands of men. It would be considered a massacre. Besides, they needed the men to fight.

Bucking tradition, the officers decided to send the most respected officers to urge the men to return to the front. The officers talked to the troops, appealing to their patriotism and their duty to replace exhausted troops. The men explained they had no problem defending the trenches. They just didn't want to take part in any more futile offensives. By the end of the day, the troops had sobered up, and they marched to the front. The few men who still refused to go were arrested and taken away. No one else in the 2nd Division was punished.

Soon, more and more units refused to obey orders to march to the front. With the German Army only 60 miles from Paris, this crisis in military discipline threatened the existence of the French nation.

Most of the mutinies in May fit the same pattern. They started at night with drunken infantry troops who were being ordered back to the front. The troops had suffered high losses in the recent offensives, and they wanted no part of future offensives. Many had read pacifist pamphlets. Most had heard about the revolution unfolding in Russia, and they wanted to force their government to end the war. They often marched on railway stations and tried to seize trains to Paris. When they sobered up, most of the troops returned to their units and went to the front. Most of the mutinies went unpunished. But the officers knew they could not rely on these troops to attack. In fact, officers had great difficulty telling which troops were dependable.

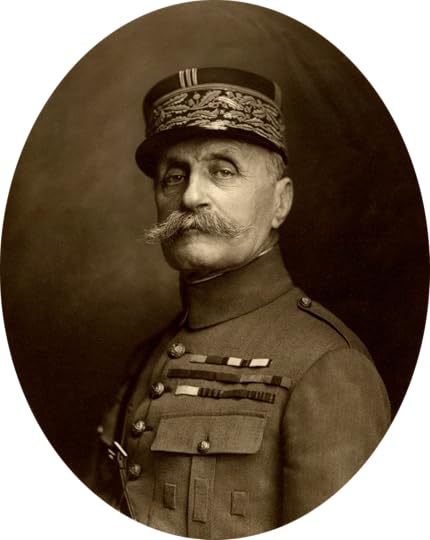

The increasing incidents of "collective indiscipline," as the military called the mutinies, ended General Nivelle's dream of a grand victory. On May 15, General Henri Philippe Petain took over as commander-in-chief. A few days later, Petain issued Directive No. 1, which suspended "large-scale attacks in depth."

The Mutinies Continue

Petain's directive basically meant that French troops would man their trenches and defend against German attack. Most French soldiers were willing to do this. One group of mutineers wearing flowers in their uniform button holes had told their stunned commander:

You have nothing to fear, we are prepared to man the trenches, we will do our duty and the [Germans] will not get through. But we will not take part in attacks which result in nothing but useless casualties . . . .

In spite of Petain's new order, the mutinies continued and even grew in number and scope. The men complained about poor food rations and not getting leaves to visit their families. Many of them read anti-war pamphlets, sent from radical organizations in Paris. During early June, when the most serious incidents took place, units in 16 different army divisions mutinied. Veteran soldiers shot at their officers, set fire to their camps, fought with civilian and military police, and took part in drunken brawls with each other. Rebellious soldiers put their thumbs down and shouted "End the War!" at trucks of soldiers heading to the front. Desertions increased. Through it all, thousands of men disobeyed orders to go to the front. "We won't go up!" became their motto.

Petain Stops the Mutinies

Shocked at the fast-spreading mutinies, General Petain concluded in early June that the French Army was "unfit to fight." He found he could rely on only two divisions to stop the Germans from marching to Paris.

By mid-June, Petain had started to implement a list of immediate and long-term reforms of the army designed to stop the mutinies. Many of his reforms, such as granting seven-day leaves every four months, also attempted to lift soldier morale. He also demanded harsh punishment for those guilty of mutiny. "Mutineers drunk with slogans and alcohol, " he wrote, "must be forced back to their obedience."

Petain pressed his officers to identify, court martial, and swiftly punish the leaders of the mutinies. The problem was that when large numbers of soldiers all refused to follow orders at once, finding leaders was difficult. In many cases, the mutinies appeared to be spontaneous, without any leaders. It was not practical to court-martial and punish an entire unit of soldiers because the men were needed to fight.

Petain held General Emile Taufflieb as a model for his officers to follow. At the beginning of June, Taufflieb had handled a mutiny of a battalion of 700 men. The men were marching to the front when on a prearranged signal, they disappeared into the forest and hid in a large cave. Against the advice of his officers, Taufflieb entered the cave unarmed. He asked the men why they had mutinied. When the men had trouble articulating an answer, he told them their duty was to return to their unit. He told them to return by morning or they would face the consequences. Taufflieb gave orders to his soldiers surrounding the cave to fill it in if the men failed to come out by the deadline. The next morning the men returned. Taufflieb asked his officers to select 20 men at random from the battalion. These men were immediately court-martialed and sentenced to death. The others returned to the front.

With the support of Petain, officers punished mutinous troops by court-martialing the leaders. When they often couldn't determine the leaders, they sometimes chose known troublemakers, men with civilian criminal records or those who complained a lot. Or they followed Taufflieb's example and selected every 10th or 20th man standing in the ranks. (This method even had precedent in history. When the ancient Roman army put down mass mutinies, they killed every 10th soldier who mutinied. This is the origin of the word "decimate.")

By the end of June, Petain's army reforms and policy of severe punishment for mutiny began to have an effect. The mutinies decreased and eventually ended.

There were 110 cases of "grave collective indiscipline" reported between April and September 1917. These cases of mutiny occurred in 50 divisions that made up over half of the French Army. At least 100,000 soldiers (out of an army of 4 million) were involved in the mutinies which mainly took place just behind the French lines.

According to official French records, of those court-martialed for mutiny, 3,427 were found guilty. More than 500 received the death sentence, but only 49 were executed. Most of those convicted of mutiny were assigned to disciplinary military units or deported to prisons outside France. But the official records are probably wrong about the number of executions. Some mutineers faced charges other than mutiny and were shot. Many others undoubtedly were shot without any trial and listed as "dead in action."

The Germans received reports of mutinies in the French Army from spies and escaped prisoners of war, but refused to believe such a thing was really happening. By adopting this view, Germany squandered an opportunity to push on to Paris and win the war in the summer of 1917.

(Source: http://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_A...

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/chapters/...

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/wor...

by Tony Ashworth (no photo)

by Tony Ashworth (no photo) by

by

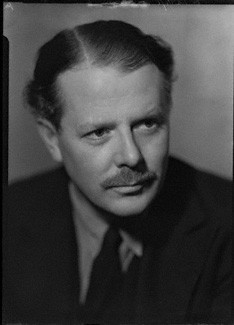

Alistair Horne

Alistair Horne by

by

John Keegan

John Keegan by Elizabeth Greenhalgh (no photo)

by Elizabeth Greenhalgh (no photo)(no image) Mutiny 1917 by

John Williams

John Williams

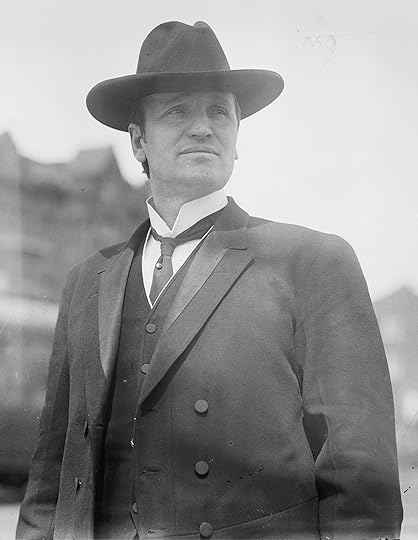

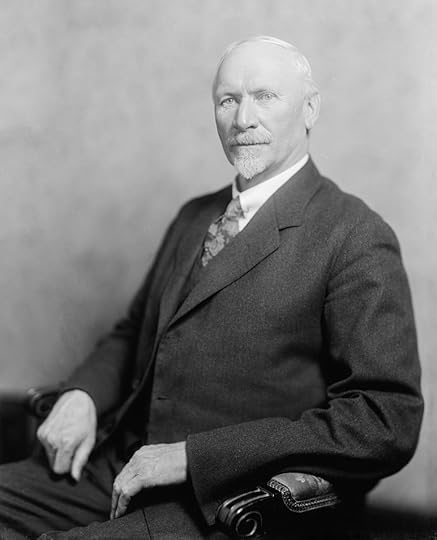

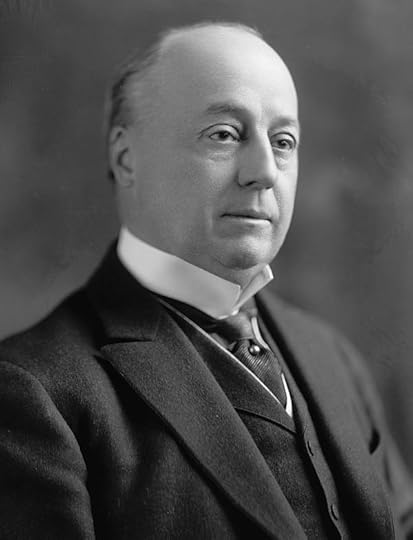

George Chamberlain

George Chamberlain

George Earle Chamberlain was born in Natchez, Mississippi in 1854. He worked there as a clerk in a general goods store for 2 years before entering Washington and Lee University. Upon graduation in 1876, he migrated to Oregon where he taught school briefly in Linn County. His political career began with his appointment as deputy clerk of Linn County, Oregon, a position he held from 1877 to 1879. After studying law in Albany, Oregon, he was elected to the state legislature in 1880, serving there until he was elected district attorney of the third judicial district of Oregon in 1884. Retiring to his law practice after one two-year term, Chamberlain was named as the State's first attorney general by Governor Sylvester Pennoyer in 1891, an office he held until 1895.

From 1900 to 1903, Chamberlain served as Multnomah County's District attorney, and was then elected governor of Oregon, serving until 1909. In that year he entered the national political arena as senator to Oregon. In Washington he was a key player in the government's preparation for World War I, serving as chair of the Senate Military Affairs Committee, which presided over such issues as the selective service draft bill and food control measures. His speech of January 24, 1918 regarding War Department inefficiency received widespread notice, although it contributed to his alienation from President Wilson and the Democratic Party establishment.

Chamberlain was defeated for re-election in 1920, in part because of his progressive Democratic allegience in a year when conservative Republicans were in favor nationally. His last government post was as a member of the U.S. Shipping Board, serving from 1921 to 1923. Married twice in his life, Chamberlain had seven children with his first wife, Sallie N. Welch, whom he wed in 1879. Carolyn B. Shelton, Chamberlain's second wife, was married to the ex-senator two years before his death in 1928.

(Source: http://nwda.orbiscascade.org/ark:/804...)

More:

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_E...

http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/gech...

http://www.ohs.org/the-oregon-history...

http://www.unz.org/Pub/Forum-1918jun-...

http://www.nga.org/cms/home/governors...

http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn...

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract...

by Ronald Schaffer (no photo)

by Ronald Schaffer (no photo) by Anne Cipriano Venzon (no photo)

by Anne Cipriano Venzon (no photo) by Edward M. Coffman (no photo)

by Edward M. Coffman (no photo)(no image) The President and His Biographer: Woodrow Wilson and Ray Stannard Baker by Merrill D. Peterson (no photo)

(no image)Senators of the United States: A Historical Bibliography, a Compilation of Works by and About Members of the United States Senate, 1789-1995 by Jo Anne McCormick Quatannens (no photo)

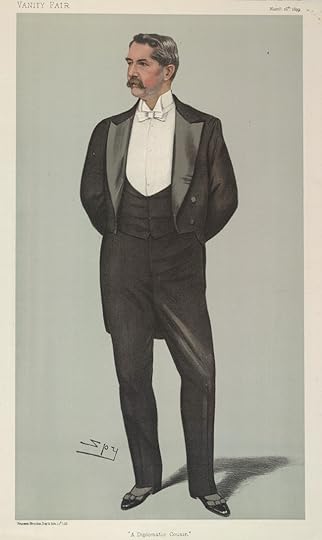

Vance McCormick

Vance McCormick

Vance Criswell McCormick was born June 19, 1872 in Harrisburg PA to Henry McCormick and Annie Criswell McCormick, Vance was by far the best-known and most celebrated McCormick, as well as one of the most influential figures in Dauphin County History.

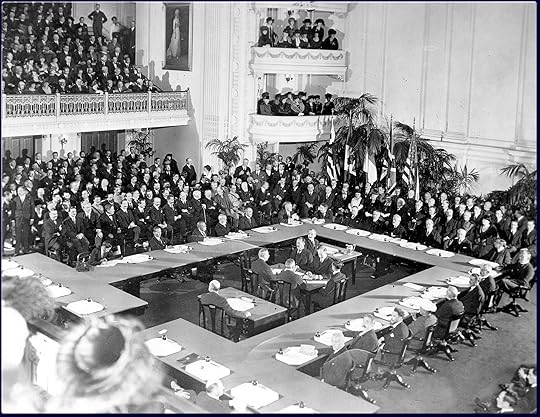

A fortunate boy who grew to be a man of great distinction, Vance was elected mayor of Harrisburg by the age of 30, and by 42, ran for governorship. At 44, he became chair of the Democratic National Committee and went on to become appointed chair of the Commission for Peace, under President Woodrow Wilson, heading up numerous clubs and organizations along the way.

Vance attended Harrisburg Academy and Phillips Andover before completing a civil engineering course at university. A Yale man by family tradition, (his uncle James, brother Henry B., and cousins Henry Jr., James, Jr. William, Donald, Robert and Henry were all alums), Vance graduated from the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University in 1893, but was given an honorary MA degree by Yale in 1907. A born athlete and leader, he became captain of the class football and baseball teams his freshman year and was on his university football team his junior and senior years, and was president of Intercollegiate Football Association his senior year. He garnered other university honors and awards, as well, including class deacon.

The athletic grace, leadership and social ease that marked his Princeton years never left him. According to reporter Paul Beers (1964), Harrisburgers remembered Vance "riding in his Rolls-Royce in later years, "walking the streets like an athlete and entertaining royally -- from Presidents to retired city patrolmen -- at his home".

A member of Harrisburg's Pine Street Presbyterian Church, Vance went into business with his father from 1893 to 1900. After the death of his father, He was trustee of the Estates of James and Henry McCormick, which operated farms, coal and mining properties, railroads and timberlands, and at various times, were officers of companies controlled by the estates. He was president of The Patriot Company, publishers of The Patriot (newspaper), from 1902-46, and The Evening News (1917-46) and Harrisburg Common Council (1900-02). He was also president of the Pinkey Mining Company.

Vance was also mayor of Harrisburg from 1902-05, and an influential personality in local politics. He instituted a million-dollar movement in Harrisburg that brought about a parks renovation project and pure water, among other initiatives.

He was chair of a committee which brought about reorganization of the Democratic Party in Pennsylvania (1910), treasurer for the State of Pennsylvania Democratic Nations Committee (1912), delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1912), 1916, 1920, 1924), Democratic candidate for governorship of Pennsylvania (1914), and chairman of the Democratic National Committee (1916-19).

Vance's work with the Democratic Party attracted the appreciation and admiration of President Woodrow Wilson. He served as Wilson's campaign manager, as chair of the War Trade Board (1916-19) and on the Commission to Negotiate Peace (1919) at Versailles. (see photo)

He was also a member of many local, state, national and international organizations.

Vance received the Commander Legion of Honor of France in 1919, and Belgium honored him with the Decoration of Grand Officer de L'Order de la Courrone in the same year. In June, 1920, he was decorated Grand Officer of the Royal Order of the Crown of Italy.

Vance remained a bachelor until the age of 52, when he married Mrs. Marlin E. Olmsted, the widow of an eight-time Republican congressman. Vance died at his country home, June 16, 1946, Cedar Cliff Farms, near Harrisburg, PA. Mrs. McCormick died in 1953.

(Source: http://hbg.psu.edu/hum/McCormick/vanc...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vance_C....

http://hbg.psu.edu/hum/McCormick/fami...

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg....

http://drs.library.yale.edu:8083/HLTr...

http://genforum.genealogy.com/mccormi...

by Vance Criswell McCormick (no photo)

by Vance Criswell McCormick (no photo) by Gerald G. Eggert (no photo)

by Gerald G. Eggert (no photo) by Linda A. Ries (no photo)

by Linda A. Ries (no photo) by Ross A Kennedy (no photo)

by Ross A Kennedy (no photo) by

by

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

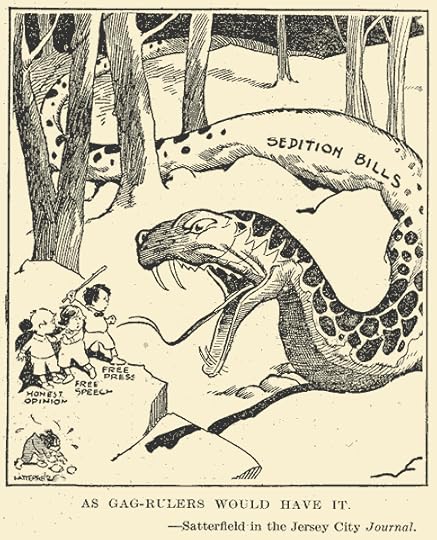

Sedition Act of 1918

Sedition Act of 1918

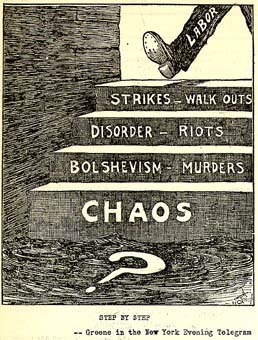

On May 16, 1918, the United States Congress passes the Sedition Act, a piece of legislation designed to protect America's participation in World War I.

Along with the Espionage Act of the previous year, the Sedition Act was orchestrated largely by A. Mitchell Palmer, the United States attorney general under President Woodrow Wilson. The Espionage Act, passed shortly after the U.S. entrance into the war in early April 1917, made it a crime for any person to convey information intended to interfere with the U.S. armed forces' prosecution of the war effort or to promote the success of the country's enemies.

Aimed at socialists, pacifists and other anti-war activists, the Sedition Act imposed harsh penalties on anyone found guilty of making false statements that interfered with the prosecution of the war; insulting or abusing the U.S. government, the flag, the Constitution or the military; agitating against the production of necessary war materials; or advocating, teaching or defending any of these acts. Those who were found guilty of such actions, the act stated, shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both. This was the same penalty that had been imposed for acts of espionage in the earlier legislation.

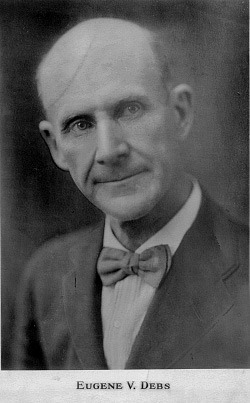

Though Wilson and Congress regarded the Sedition Act as crucial in order to stifle the spread of dissent within the country in that time of war, modern legal scholars consider the act as contrary to the letter and spirit of the U.S. Constitution, namely to the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. One of the most famous prosecutions under the Sedition Act during World War I was that of Eugene V. Debs, a pacifist labor organizer and founder of the International Workers of the World (IWW) who had run for president in 1900 as a Social Democrat and in 1904, 1908 and 1912 on the Socialist Party of America ticket.

After delivering an anti-war speech in June 1918 in Canton, Ohio, Debs was arrested, tried and sentenced to 10 years in prison under the Sedition Act. Debs appealed the decision, and the case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where the court ruled Debs had acted with the intention of obstructing the war effort and upheld his conviction. In the decision, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to the earlier landmark case of Schenck v. United States (1919), when Charles Schenck, also a Socialist, had been found guilty under the Espionage Act after distributing a flyer urging recently drafted men to oppose the U.S. conscription policy. In this decision, Holmes maintained that freedom of speech and press could be constrained in certain instances, and that The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

Debs' sentence was commuted in 1921 when the Sedition Act was repealed by Congress. Major portions of the Espionage Act remain part of United States law to the present day, although the crime of sedition was largely eliminated by the famous libel case Sullivan v. New York Times (1964), which determined that the press's criticism of public officials—unless a plaintiff could prove that the statements were made maliciously or with reckless disregard for the truth—was protected speech under the First Amendment.

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedition...

http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/e...

http://www.seditionproject.net/index....

http://nashvillepost.com/news/2007/8/...

http://www.conservapedia.com/Sedition...

by

by

Geoffrey R. Stone

Geoffrey R. Stone by Stephen M. Kohn (no photo)

by Stephen M. Kohn (no photo) by Paul L. Murphy (no photo)

by Paul L. Murphy (no photo) by William Preston Jr. (no photo)

by William Preston Jr. (no photo)(no image) The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921 by Harry N. Scheiber (no photo)

(no image) Civil Liberties In Wartime: Legislative Histories Of The Espionage Act Of 1917 And The Sedition Act Of 1918 by William H. Manz (no photo)

Kate Richard O'Hare

Kate Richard O'Hare

Kate Richards was born on March 26, 1876 to Andrew and Lucy Richards, farmers in Central Kansas. A drought in 1887, combined with the cumulative effects of the economic depression of the 1870s, completely devastated the family. Forced off their farm, the family moved to a poverty stricken area of Kansas City, where Andrew Richards barely made enough money for the family to survive.

In 1894, Kate found work as a machinist in a small Kansas City machine shop. During this year, she also met prominent socialist Mother Jones, who introduced her to Kansas City socialists and gave her books regarding socialism. This was followed in 1895 by a meeting with Eugene V. Debs, another noted socialist. In 1899, she and her father founded the Socialist Labor Party, although she later left the organization. In 1901, she was a founding member of the Socialist Party in America; she also met her future husband, Frank P. O'Hare, an Iowa born socialist from St. Louis. They were wed in January 1902, and then set out on a national lecturing and organizing tour. They eventually moved to Oklahoma in 1904, and operated a small farm there until 1908, when the family moved back to Kansas City with their four young children.

During her years in Kansas City, O'Hare remained a vocal and active supporter of socialism. She toured many southwestern states, often for the length of an entire summer. Her popularity was said to be second only to Eugene Debs himself. She also became a militant supporter of women's suffrage. She served as grand marshal for a suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. in 1913. Both in 1910 and in 1916, she ran for political office, even though women did not have the right to vote.

Kate Richards O'Hare was strongly opposed to United States entry into World War I. She toured throughout the nation, presenting a speech entitled "Socialism and the War." On July 17, 1917, she addressed a crowd in Bowman, North Dakota. The Bowman speech was the 76th time she had given the address. This time, however, she was arrested under the auspices of the 1917 Espionage Act. She was tried and convicted before a court in Bismarck, North Dakota, and was sentenced to five years in prison, to begin on April 15, 1919. In May 1920, her sentence was commuted and she was set free.

She remained active in her post-prison years. She led a march to Washington D.C. in 1922 to protest the treatment of opponents of the war, helped to organize a socialist college in Arkansas in 1925 and was active in Upton Sinclair's "End Poverty in California" campaign in 1928. She was especially active in the area of prison reform. She made her greatest contribution to that field in the state of California, where she was appointed Director of Penology. She directed many reforms of that state's penal system.

Kate Francis O'Hare died on January 12, 1948 at the age of 71.

(Source: http://webapp.und.edu/dept/library/Co...)

More:

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kate_Ric...

http://womhist.alexanderstreet.com/kr...

http://digital.library.okstate.edu/en...

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/43/

by Sally M. Miller (no photo)

by Sally M. Miller (no photo) by Peter H. Buckingham (no photo)

by Peter H. Buckingham (no photo) by Suzanne H. Schrems (no photo)

by Suzanne H. Schrems (no photo)(no image) In Prison by Kate Richards O'Hare (no photo)

(no image) Kate Richards O'Hare: Selected Writings and Speeches by Kate Richards O'Hare (no photo)

Rose Pastor Stokes

Rose Pastor Stokes

Born Rose Harriet Wieslander in Augustova, Poland, on July 18, 1879, she was the first child of a loveless marriage. At age three, she moved to England with her mother, leaving her father (whom she knew only as “Jacob the Learned Bootmaker”) and the pogrom-threatened shtetl behind. Living with relatives in the squalid slums of London’s East End, Rose was compelled by necessity to leave school at age eight and join the workforce. In England Rose’s mother, Hindl, married Israel Pastor, who soon decided to resettle the family in America. In 1890, Hindl, Rose, and the new baby Maurice joined Pastor in Cleveland, where Rose found work in a “buck-eye,” the cigar-sweatshop in which many Jews labored. She worked as an unskilled “stogey-roller” for twelve years. After Israel Pastor abandoned the family, she became the sole supporter of six. For those who later popularized her character in the media, this period of her life often faded to an idealized working-class experience, but for Rose herself, it stood out as formative for her identity.

Her love of reading impelled her to respond to a call for letters in the Yidishes Tageblat [Jewish daily news]. In 1901, her first letter was published on the Tageblat’s English page, and she soon became a regular contributor. Her column gained such popularity that the editor offered her a full-time position as a resident columnist in New York City for the enticing salary of $15 per week. She settled in the Lower East Side in January 1903, within a few months joined by her mother and some of her siblings.

Her work at the Tageblat provided her with a forum to explore political themes and brought her into contact with ghetto intelligentsia. It was also through the Tageblat that she met her future husband. As part of a series on settlement workers, Rose interviewed James Graham Phelps Stokes, a reform-minded millionaire from a prominent family. After the publication of this interview, Pastor and Stokes became fast friends. Their relationship took a more intimate turn at the end of the summer of 1904, and they began to discuss marriage.

The news of this unlikely engagement broke on the front page of the New York Times on April 6, 1905, with a headline reading “J. G. Phelps Stokes to Wed Young Jewess—Engagement of Member of Old New York Family Announced—Both Worked on East Side.” The article sensationalized the romantic story and the sharp contrasts in background between the two, calling her the “Cinderella of the sweatshops.”

Although the great disparity in class background between Pastor and Stokes was to become the central—and divisive—issue in the course of their marriage as well as in historical hindsight, the issue of religion provoked the most concern at the time of their engagement. The class distinction between them, however, constituted material for romantic fantasy. A love that overcame social barriers appealed to the public as a living fairy tale, as well as an example of the classic American success story.

From the first time that Stokes and Pastor discussed marriage, they determined to remain in the world of the Lower East Side, yet she joined his world of philanthropic reformism. Both quickly became disillusioned with settlement work, however, and in 1906, they joined the Socialist Party of America. She became one of the most prominent speakers on the Intercollegiate Socialist Society tour.

Stokes defined her new role as the voice of the worker, with the responsibility to use her newfound influence to help the working class. Although she stated, “I believe ... that the Jewish people, because of the ancient and historic struggle for social and economic justice, should be fitted to recognize a special mission in the cause of the modern Socialist movement,” she resisted ethnic specificity and association with Jewish organizations, defining allegiance only along class lines.

After devoting herself to the lecture circuit for ten years, Stokes applied her political energy to labor activism and to organizations outside the formal structure of the Socialist Party. She led the movement in support of Patrick Quinlan, a strike leader of the radical Industrial Workers of the World. In New York in 1912, she spearheaded a campaign to organize chambermaids into a branch of the International Hotel Workers’ Union and to encourage them to strike. Stokes also garnered a great deal of attention for her birth control activism, serving as a leader of the groups that agitated in support of Margaret Sanger during the time of her arrest and trial, and writing two pro–birth control plays, The Woman Who Wouldn’t and Shall the Parents Decide (cowritten with Alice Blache). Stokes became involved in the cause of birth control because it provided a means of doing direct, concrete work for the benefit of the working class. Her distinctive position made her particularly successful in this cause, for her working-class background gave her argument a personal legitimacy, while her upper-class position protected her from arrest.

Public attention to Stokes reached its peak over her antiwar activism, culminating in her arrest on March 22, 1918, for an antiwar speech in Kansas City, Missouri, and a letter to the local paper in which she declared, “No government which is for the profiteers can also be for the people, and I am for the people, while the government is for the profiteers.” Stokes’s conviction was appealed twice before the decision was reversed in March 1920, on the grounds that the charge to the jury was prejudicial against the defendant.

The arrest and trial of Stokes attracted a great deal of notoriety and only exacerbated the tension within her marriage, which ended in divorce in 1926. Stokes had moved toward a radicalism increasingly incompatible with her husband’s position as a millionaire socialist. She was present at the 1919 socialist convention in Chicago, at which the Communist Party of America was founded, and she held a position on the CP Central Executive Committee. As an American delegate to the Comintern’s Fourth World Congress in Moscow in 1922, Stokes submitted a minority report on the “Negro question.” Although she had been wary of separate organizations for women during her involvement in the Socialist Party, she began to advocate a special organization for women in the Communist Party and took on the job of managing the Women’s Work Department of the Central Executive Committee.

While she remained devoted to radical activism, the last ten years of Stokes’s life were filled with emotional and financial strain. Making no financial demands on her ex-husband except for a monthly stipend for her mother, Stokes depended on her writing as her primary source of income. She remarried in 1927, to Jerome Isaac Romain (who later changed his name to Victor J. Jerome), a Russian-Polish Jew active in the Communist Party. Due to their financial needs, Romain lived and worked in New York, while Stokes remained at her house in Westport, Connecticut, taking care of Romain’s young son and continuing her political activism.

In 1930, Stokes was diagnosed with a malignant breast tumor, which she attributed to having received a blow on the breast from a policeman’s club during a demonstration—claiming martyrdom for the proletarian cause. Her health rapidly declined; even so, she maintained her radical, fighting spirit. Although her illness prevented her from remaining active in the Communist Party during the last years of her life, she continued to assert her allegiance to it. On June 20, 1933, she died in Germany, where she had sought medical care at an experimental clinic.

Stokes’s complicated identity continued to confound historians, writers, and thinkers after her death. Some have located her importance in her sensational marriage, emphasizing her connection to the Phelps-Stokes family over and above her political significance and activism. In contrast, the Communist Party, as the custodian of her memory after her death, sought to construct from her character and experiences a model for the party that fit neatly—more neatly than Stokes did herself during her lifetime—into party ideology.

Stokes used her autobiography, which she began in 1924, as a forum to negotiate these tensions in her identity, rewriting her own background and balancing the visions that others had of her life and mission. When she became too ill to continue writing, she entrusted the project of its completion to Samuel Ornitz, a communist writer, friend, and later member of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten, who finally abandoned it in 1937. In her autobiography as in her life, Stokes fused American values of self-improvement with immigrant and socialist ideals of community.

(Source: http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/s...

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_Pas...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

https://www.marxists.org/subject/wome...

http://drs.library.yale.edu:8083/HLTr...

by Arthur Zipser (no photo)

by Arthur Zipser (no photo) by Herbert Shapiro (no photo)

by Herbert Shapiro (no photo) by Morris Rosenfeld (no photo)

by Morris Rosenfeld (no photo) by Joyce Antler (no photo)

by Joyce Antler (no photo)(no image) The Woman who Wouldn't by Rose Pastor Stokes (no photo)

U.S. v. Eugene Debs

U.S. v. Eugene Debs

The Debs Federal Court Trial (U.S. v. Eugene V. Debs) in Cleveland resulted from an antiwar speech that the Socialist leader gave in Canton, OH, on 16 June 1918. Debs was charged with violation of the Espionage Act. The trial, which took place in Judge David C. Westenhaver's court from 9-12 Sept. 1918, captured national interest. U.S. District Attorney Edward S. Wertz, assisted by Francis B. Kavanagh and JOSEPH C. Breitenstein, was in charge of the government's case; Debs was represented by Seymour Stedman, William A. Cunnea, Joseph Sharts, and Morris Wolf; Charles Ruthenberg was among the chief witnesses.

The trial centered around the content of Debs's Canton speech. In the speech, Debs espoused freedom of speech and the goals of international socialism, denounced war, expressed solidarity with the Bolsheviks, and praised the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The antiwar sentiments around which the prosecution built its case were focused on one sentence: "The master class has always declared the wars, the subject class has always fought it." No witnesses were called for the defendant; rather, Debs defended his actions directly to the jury. The jury found him guilty on 3 counts: attempting to incite insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, and refusal of duty in the armed forces of the U.S.; obstructing and attempting to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service; and uttering language to incite, provoke, and encourage resistance to the U.S. Judge Westenhaver sentenced Debs to 10 years' imprisonment pending an appeal to the Supreme Court, which upheld Deb's conviction. Debs was pardoned by Pres. Warren Harding in 1921.

(Source: http://ech.case.edu/cgi/article.pl?id...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debs_v._...

http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/p...

http://debs.indstate.edu/e13t7_1918.pdf

http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects...

http://www.oyez.org/cases/1901-1939/1...

by Nick Salvatore (no photo)

by Nick Salvatore (no photo) by Ray Ginger (no photo)

by Ray Ginger (no photo) by Ernest Freeberg (no photo)

by Ernest Freeberg (no photo) by David Karsner (no photo)

by David Karsner (no photo)(no image) The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921 by Harry N. Scheiber (no photo)

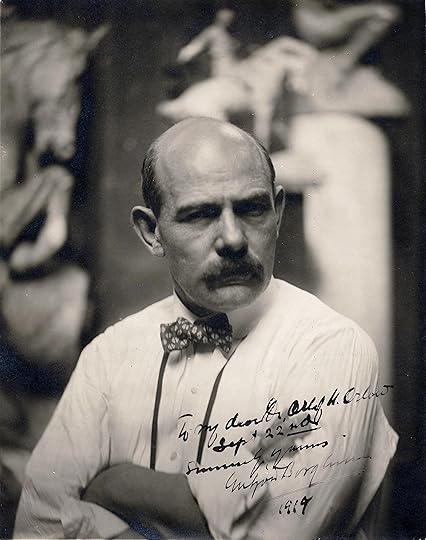

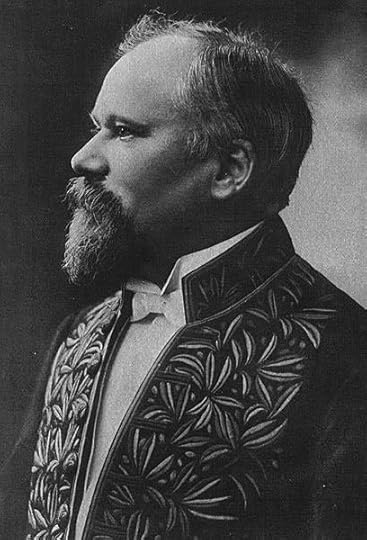

Gutzon Borglum

Gutzon Borglum

BORGLUM, JOHN GUTZON DE LA MOTHE (1867–1941). Gutzon Borglum, painter and sculptor, was born in Idaho on March 25, 1867, the son of Danish immigrants James and Ida (Michelson) Borglum. He first studied art in California under William Keith and Virgil Williams. There the large painting Stagecoach, now in the Menger Hotel in San Antonio, was completed. In 1890 Borglum went abroad to study for two years in Paris at the Académie Julien and the École des Beaux Arts and also under individual masters, the most important of whom was Auguste Rodin. Borglum exhibited in the Old Salon in 1891 and 1892 as a painter and in 1891 in the New Salon as a sculptor with Death of the Chief, for which he was awarded membership in the Société des Beaux-Artes.

After a year of work in Spain he returned to California, in 1893, and from there went to England in 1896. In England he painted portraits and murals, illustrated books, and produced sculpture. Apache Pursued, executed at this time, is owned in replica by the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Sculpture became Borglum's prime artistic medium; examples of his work include the head of Lincoln (1908) at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., a seated bronze sculpture of Lincoln (1911) in Newark, New Jersey, two equestrian statues of Philip H. Sheridan (1907, 1924), and the Wars of America group (1926). The most famous and monumental of his works are the sculptures at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota, of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. These were dedicated on August 10, 1927, and completed, after Borglum's death, by his son Lincoln.

In 1925 the sculptor moved to Texas to work on the monument to trail drivers commissioned by the Trail Drivers Association. He completed the model in 1925, but due to lack of funds it was not cast until 1940, and then was only a fourth its originally planned size. It stands in front of the Texas Pioneer and Trail Drivers Memorial Hall next to the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Borglum lived at the historic Menger Hotel, which in the 1920s was the residence of a number of artists. He subsequently planned the redevelopment of the Corpus Christi waterfront; the plan failed, although a model for a statue of Christ intended for it was later modified by his son and erected on a mountaintop in South Dakota. While living and working in Texas, Borglum took an interest in local beautification. He promoted change and modernity, although he was berated by academicians.

Borglum was married to Mrs. Elizabeth Putnam in 1889; the marriage ended in divorce in 1908. On November 6, 1941, Borglum died in Chicago, Illinois, survived by his wife, Mary (Montgomery), and his two children. He was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

(Source: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/on...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gutzon_B...

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rushmore...

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug97/ston...

http://www.nps.gov/moru/historycultur...

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history...

by John Taliaferro (no photo)

by John Taliaferro (no photo)(no image) My Father's Mountain by Lincoln Borglum (no photo)

(no image) Six Wars at a Time: The Life and Times of Gutzon Borglum, Sculptor of Mt. Rushmore by Howard Shaff (no photo)

(no image) Gutzon Borglum: The Man Who Carved a Mountain by Willadene Price (no photo)

John K. Shields

John K. Shields

John Knight Shields (August 15, 1858 – September 30, 1934) was a Democratic United States Senator from Tennessee from 1913 to 1925.

Shields was born at his family's estate "Clinchdale", near the early pioneer settlement of Bean's Station, Tennessee in Grainger County. His education as a youth was by private tutors, a sign of the family's affluence. He studied law and was admitted to the Tennessee bar in 1879. He practiced in the counties surrounding his home until 1893, when he was named Chancellor of the former 12th Chancery Division. The next year, he resumed private practice in nearby Morristown, in Hamblen County.

In 1902 Shields became an Associate Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court, an office which he held until 1910 when he was named Chief Justice. He resigned that post in 1913, becoming the last Tennessean elected to the U.S. Senate by the Tennessee General Assembly prior to the 17th Amendment coming into effect. Shields was popularly reelected in 1918 but in 1924 lost the Democratic nomination to Lawrence Tyson, and returned to the private practice of law, this time in Knoxville.

While in the Senate, Shields served as the chairman of several committees. He chaired the Committee on Canadian Relations in the 63rd and 64th Congresses, the Committee on Interoceanic Canals in the 65th Congress, and the Committee on the Sale of Meat Products in the 66th Congress.

Shields died at his estate "Clinchdale" and is buried in Knoxville's Memorial Cemetery.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_K._...)

More:

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

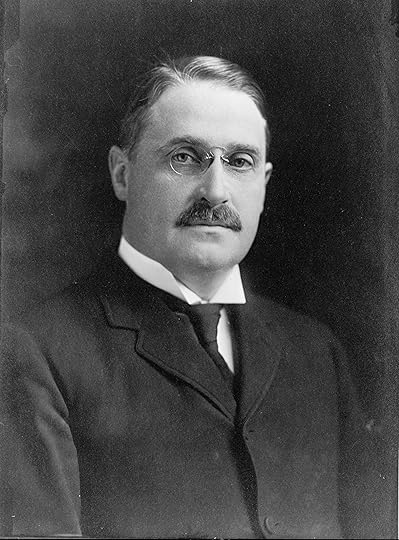

Thomas W. Hardwick

Thomas W. Hardwick

Thomas William Hardwick was born on December 9, 1872, in Thomasville to Zemula Schley Matthews and Robert W. Hardwick. In 1892 he graduated from Mercer University in Macon. A year later he left the University of Georgia's Lumpkin Law School with a law degree and was admitted to the Georgia bar. In 1894 he married Maude Perkins, and together they had one daughter, Mary. His wife died in 1937, and the following year Hardwick married Sallie Warren West.

Hardwick ran his own law practice from 1893 to 1895, when he became the Washington County prosecutor. In 1897 he ran for the Georgia House of Representatives and served as a legislator for the next four years, until he won a seat in the U.S. House, where he served his district until 1914.

When U.S. senator Augustus O. Bacon died in office, Hardwick took his seat in a special election in 1914 and stayed for five years in the U.S. Senate, where he became known for his opposition to U.S. president Woodrow Wilson's war-preparedness legislation. William J. Harris subsequently defeated Hardwick in the 1918 Democratic primary.

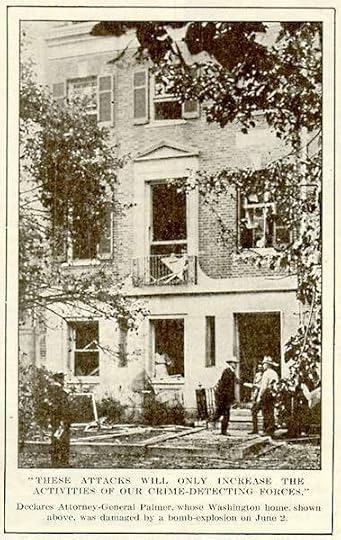

In spring 1919 Hardwick, along with several other national politicians and judges, as well as several Catholic churches, was the target of a mail bomb. He was not injured, but his housekeeper, who opened the package, was maimed. The U.S. attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, ordered the detention of 4,000 suspected Communists (mainly immigrants from the Soviet Union) in what was called the Palmer Raids.

They were held without bail, and many were deported without trials. The raids continued throughout the year and extended to union halls, homes, and anywhere socialist sympathizers or revolutionaries were thought to be gathered. In all, around 10,000 people were rounded up before the raids ended in 1920.

In 1921 Hardwick rebounded to win the Georgia governor's office, a position he held until 1923. Although he had led efforts to disenfranchise Georgia blacks at the turn of the twentieth century, as governor Hardwick proved to be somewhat more progressive. He opposed the rise of the new Ku Klux Klan and advocated prison reform, issuing an executive order that ended the common practice of flogging inmates.

Hardwick also passed Georgia's first gas tax to build new roads and pushed for a graduated state income tax, which would not be adopted until 1931. Yet he was most noted for selecting Rebecca Latimer Felton as the first woman to the U.S. Senate. Motivated partly for selfish reasons, Hardwick made the appointment after Thomas E. Watson died in office. He wanted to run for Watson's seat and hoped that appointing a woman, who would not even serve in office due to the fact that Congress was out of session, would make his road back to the Senate easier by winning him women's votes. Instead, Hardwick lost the election to Walter F. George, who waited to take his new seat so that Felton could be sworn in as the first female senator, even though her term lasted only twenty-four hours.

In the 1922 gubernatorial campaign, Clifford Walker, a supporter of the Ku Klux Klan, defeated Hardwick. Hardwick spent the following year as a special assistant to the U.S. attorney general. In 1924 Hardwick again lost a Senate election, and in 1932 he lost his bid for governor in the Democratic primary. Later, he provided legal representation to the Soviet ambassador to the United States and urged the U.S. government to recognize the Soviet Union.

Hardwick maintained a law practice in Atlanta, Sandersville, and Washington, D.C., until his death from a heart attack on January 31, 1944. He was buried in the Old City Cemetery in Sandersville, where a state historical marker stands in his honor at the courthouse square.

(Source: http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/ng...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_W...

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/...

http://russelldoc.galib.uga.edu/russe...

by James F. Cook (no photo)

by James F. Cook (no photo)(no image) Senators From Georgia by Josephine Mellichamp (no photo)

Third Battle of the Aisne

Third Battle of the Aisne

In the early morning hours of May 27, 1918, the German army begins the Third Battle of the Aisne with an attack on Allied positions at the Chemin des Dames ridge, in the Aisne River region of France.

By mid-May 1918, General Erich Ludendorff, mastermind of the ambitious German offensive—known as the Kaiserschlacht, or the "kaiser's battle"—launched that spring, was determined to reclaim Chemin des Dames from the French with a forceful, concentrated surprise attack on the strategically crucial ridge. There had been two previous battles in the Aisne region, in 1914 and 1917, but both had been offensives by the Allies—predominately the French—against the Germans; the second was part of the failed Nivelle Offensive, named for Robert Nivelle, the French commander in chief who was summarily replaced in the wake of the offensive's disastrous outcome. Nivelle's successor, Phillipe Petain, was aware of the likelihood of a German attack at the Chemin des Dames in 1918, but he failed to anticipate its strength and scale.

In the early morning hours of May 27, 4,000 German guns opened fire on a 24-mile-long stretch of the Allied lines, beginning the Third Battle of the Aisne. The Germans advanced 12 miles deep through the French sector of the lines near Chemin des Dames, demolishing four entire French divisions. Four more French and four British divisions fell between the towns of Soissons and Reims, as the Germans reached the Aisne in less than six hours. By the end of the day, Ludendorff's men had driven a wedge 40 miles wide and 15 miles deep through the Allied lines.

Earlier that month, the political and military chiefs of France and Britain had invested supreme control over their joint military strategy on the Western Front to Ferdinand Foch, chief of the French general staff. Foch's control over the other commanders in chief proved relatively limited in this instance, however, as he was unable to force Britain's Douglas Haig to transfer more than five British divisions to relieve French troops. The Germans were not as successful elsewhere on the Western Front, however, as an Allied force including some 4,000 Americans scored a major victory at Cantigny, on the Somme River, on May 28. Even as the German spring offensive continued in force, the Allied defense was stiffening, and as the summer of 1918 began, Petain, Foch and the rest of the Allied commanders began to shift their focus to counterattacks, knowing the outcome of World War I hung in the balance.

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Ba...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15937/...

http://www.chemindesdames.fr/default....

by Martin Marix-Evans (no photo)

by Martin Marix-Evans (no photo) by

by

Peter Hart

Peter Hart by Martin Gilbert (no photo)

by Martin Gilbert (no photo) by

by

John Keegan

John Keegan by Mark Ethan Grotelueschen (no photo)

by Mark Ethan Grotelueschen (no photo) by James H. Hallas (no photo)

by James H. Hallas (no photo)

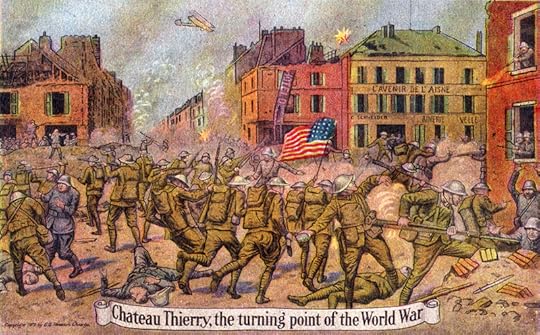

The Battle of Château-Thierry

The Battle of Château-Thierry

The Battle of Château-Thierry of 3-4 June 1918 was part of the Allied response to the German Aisne offensive of 27 May-7 June 1918 (First World War). That offensive had seen the Germans advance thirteen miles on the first day, the largest single day advance since 1914. Over the next few days the Germans had reached the Marne at Château-Thierry, thirty seven miles from Paris.

Although General John Pershing, the commander of the American expeditionary force in France was committed to the idea of concentrating his troops in a single army, in the crisis caused by the German offensives he agreed to the deployment of the 2nd and 3rd American Divisions. The 3rd Division was sent to Château-Thierry to defend the bridges over the Marne.

The Americans reached Château-Thierry on 1 June and held off the final German attacks of the Aisne offensive. Having protected the bridges at Château-Thierry, the American 3rd Division then took part in a counter-attack against German forces that had crossed the Marne further east, at Jaulgonne. On 3-4 June the Americans, supported by a number of French troops, pushed the Germans back across the river.

The battle of Château Thierry was the second American victory of the war, coming only three days after the first, at Cantigny on 28 May. A further success would follow at Belleau Wood later in June. These early American successes played an important role in the eventual Allied victory as the seemingly endless stream of fresh American troops began to destroy German morale.

(Source: http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://web.archive.org/web/2003122618...

http://www.usaww1.com/American-Expedi...

http://www.abmc.gov/memorials/memoria...

http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/ct_dm.htm

by David Bonk (no photo)

by David Bonk (no photo) by Jessie Graham Flower (no photo)

by Jessie Graham Flower (no photo) by John W. Thomason (no photo)

by John W. Thomason (no photo) by John R Mendenhall (no photo)

by John R Mendenhall (no photo)(no image) When the tide turned; the American attack at Chateau Thierry and Belleau Wood in the first week of June, 1918 by Otto Hermann Kahn (no photo)

The Battle of Belleau Wood

The Battle of Belleau Wood

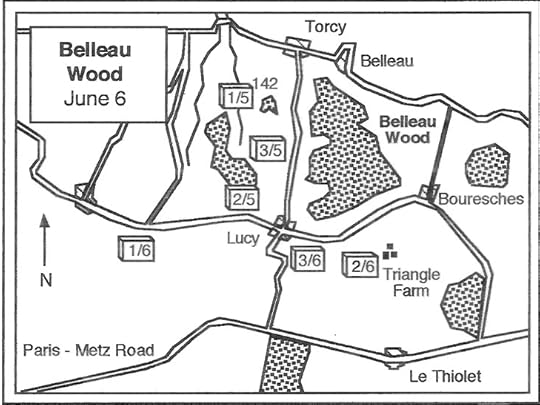

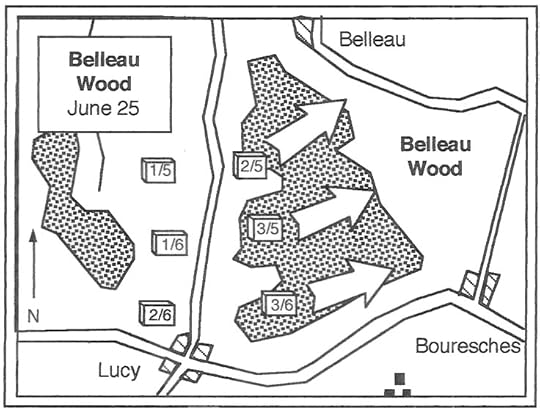

The battle fought in Belleau Wood (June 1918) was the first real taste of battle for the US Marines in World War One with General Pershing calling Belleau Wood the most important battle fought by US forces since the US Civil War. The Battle of Belleau Wood was part of the Allied drive east away from an axis from Amiens to Paris in what was a response to the German Spring Offensive in 1918.

During the Spring Offensive, the Germans had come dangerously close to breaking the Allied lines protecting Amiens and Paris. Ludendorff’s force was strengthened by a huge influx of experienced German soldiers who had fought in Russia. However, as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1917), Russia had pulled out of World War One and Germany, therefore, could move her soldiers to the Western Front. The German push, ironically, was so successful that those at the front – Stormtroopers who had done so much damage to the Allied front line – could not be supplied and their advance slowed to a halt short of Amiens. Along the line of advance, however, the Germans had constructed heavily defended positions that while in place threatened cities such as the major rail hub at Amiens and Paris itself. One such place was Belleau Wood.

The task of clearing Belleau Wood was given to the 2nd and 3rd Divisions of the US Army. Half of the 2nd Division was made up of units of the US Marines (the 4th Marine Brigade, which comprised of the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments).

To get to the woods, the Marines had to cross wheat fields and meadows. The Germans had placed their machine guns in a way that they could continuously sweep these fields with accurate and high intensity fire. The Marines had to launch six attacks on German positions in Belleau Wood that were for the most part difficult to identify in an initial attack because they were so well positioned. The wood itself was also made up of closely packed trees that made any advance difficult in the extreme.

Caught in the open fields or in the densely packed wood, French officers advised the Marines to turn back. This they refused to do. US Marine Captain Lloyd Williams said in response to this, “Retreat? Hell, we just got here.”

US Marine casualties were the highest in the Corp’s history up to that date. However, once units got into the woods, the trees that hindered a swift advance also became a source of protection. Marine snipers could pick-off German machine gun posts with some ease. Once a machine gun fired, it gave away the position of the machine gun team. General Pershing was to state that “the deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle.” Even a post-battle German report stated that the Marines marksmanship was “remarkable”.

By June 26th, the Marines confirmed that they had taken the entire woods. To clear the woods in their entirety, the Marines had frequently resorted to hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and knives. Such was the ferocity of this that the Germans gave the Marines the nickname “Teufel Hunden”, which roughly translates as “Devil Dogs”.

The success of the US Marines in clearing such a strategically important place came at a cost. Out of the 9,777 US casualties, 1,811 were fatalities. No one is quite sure about German casualties because the end of the battle at Belleau Wood corresponded with a general German withdrawal along the whole front. Over 1,600 German prisoners were taken, so it is assumed that German casualties were high.

In terms of overall casualty figures, the casualties at the Somme and Verdun dwarf the number of deaths at Belleau Wood. However, the psychological damage the defeat had on the German military cannot be underestimated. The Germans were in a very well defended stronghold with a sweep of fire that was to prove deadly. Few in the German military hierarchy would have expected the woods to fall so quickly. Not only was the defeat of the Germans at Belleau Wood a major blow to the Germans it also proved to be a huge morale booster to the Allied forces that were still suffering from the onslaught that was the German Spring Offensive. After the battle, the French renamed Belleau Wood “Bois de la Brigade de Marine” – Wood of the Marine Brigade and the 4th Brigade was awarded the Croix de Guerre by the French in recognition of their achievement.

(Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/w...

http://www.defense.gov/News/NewsArtic...

http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlMV-c...

http://www.marines.com/videos/-/video...

http://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/ph...

by David Bonk (no photo)

by David Bonk (no photo) by David J. Ulbrich (no photo)

by David J. Ulbrich (no photo) by J. Robert Moskin (no photo)

by J. Robert Moskin (no photo) by Robert B. Asprey (no photo)

by Robert B. Asprey (no photo) by Alan Axelrod (no photo)

by Alan Axelrod (no photo) by Dick Camp (no photo)

by Dick Camp (no photo) by Rexmond C. Cochrane (no photo)

by Rexmond C. Cochrane (no photo) by Louis C. Linn (no photo)

by Louis C. Linn (no photo) by Robert Wallace Blake (no photo)

by Robert Wallace Blake (no photo)

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel

the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under the command of General John J. Pershing launches its first major offensive operation as an independent army during World War I.

After lending much-needed support to the exhausted French forces at Belleau Wood in June 1918 and in the Second Battle of the Marne in July, Pershing and Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch decided that the 1st Army of the AEF should establish its headquarters in the Saint-Mihiel sector and prepare a front facing the Saint-Mihiel salient, a triangular wedge of land between Verdun and Nancy, in northeastern France, that had been occupied by the Germans since the fall of 1914. By heavily fortifying the area, the Germans had effectively blocked all rail transport between Paris and the Eastern Front. In mid-August, the AEF was given the task of leading an attack on the salient; it would be its first independent operation of the war.

The attack began on September 12, 1918, with the advance of Allied tanks across the trenches at Saint-Mihiel, followed closely by the AEF’s infantry troops. Foul weather plagued the offensive as much as the enemy troops, as the trenches filled with water and the fields turned to mud, bogging down many of the tanks. Despite the conditions, the attack proved successful—in part because the German command made the decision to abandon the salient—and greatly lifted the morale and confidence of Pershing’s young army. By September 16, 1918, Saint-Mihiel and the surrounding area were free of German occupation. The American forces immediately shifted further south, to a new offensive near the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River, where they combined with British and French forces to further hammer the Germans, as the Allies moved ever closer to victory in World War I.

(Source: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/...

http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/w...

http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/stmihiel...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvxEtV...

http://www.shsu.edu/~his_ncp/Pershing...

http://iagenweb.org/greatwar/cemeteri...

by David Bonk (no photo)

by David Bonk (no photo) by James H. Hallas (no photo)

by James H. Hallas (no photo) by Walter R McClure (no photo)

by Walter R McClure (no photo) by

by

Carlo D'Este

Carlo D'Este(no image) The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Volume III: The Battle of St. Mihiel by Maurer Maurer (no phto)

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

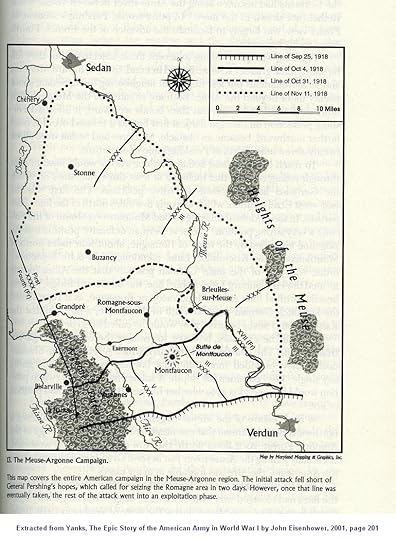

The Meuse-Argonne offensive, 26 September-11 November 1918, was the southern part of the great triple offensive that broke the German lines on the Western Front. It was also the biggest battle fought by the American Expeditionary Force during the war.

Ferdinand Foch’s plan called for three offensives aimed at forcing the Germans out of France and Belgium. In the north the Belgians, British and French would attack through Flanders. In the centre the British and Empire forces attacked the Hindenburg Line between Cambrai and St. Quentin. Finally to the south the French and Americans would attack between Reims and Verdun, along the Meuse and through the Argonne Forest.

The Meuse-Argonne offensive would be launched by the American First Army, under General John Pershing, and the French Fourth Army under General Henri Gourand. The Americans held the eastern part of the line, from Forges on the Meuse, north west of Verdun, to the centre of the Argonne Forest. The French Fourth Army then took over to Auberive to the Suippe, east of Reims. The Americans faced a very difficult task. The German lines were up to twelve miles deep, and had been under development since 1915. The second line was based on the hill of Montfaucon, the third line (the Hindenburg Line) on hills at Romagne. The entire area was hilly and wooded, cut by steep sided valleys, many running across the proposed line of advance.

The area was also badly supported by road and rail links. The Americans had only recently fought a battle at St Mihiel, (12-13 September 1918), east of Verdun, and Pershing had to transfer 600,000 men along three minor roads to reach his new front west of the city. The fighting at St. Mihiel had also inflicted heavy losses on some of Pershing’s best units, and so the attack in the Argonne had to be made with many fresh inexperienced troops.

The combined Franco-American attack began on the morning of 26 September. Over the first five days the French advanced nine miles, penetrating deeply into the German lines. The Americans did less well. Their attacks were enthusiastic, determined but not always well organised. Along the Meuse they were able to advance five miles, but in the Argonne forest they were only able to move two miles. By the start of October the divisions used in the initial assault were exhausted, and Pershing was forced to order a halt while new divisions replaced them in the line. During this period Foch came under great pressure from Clemenceau to replace Pershing, but Foch was well aware of the difficulties facing the Americans and stood his ground.

The second phase of the battle began on 4 October. The Americans launched a series of costly frontal assaults that finally began broke through the main German defences between 14-17 October. By the end of October the Americans had advanced ten miles and had finally cleared the Argonne Forest. On their left the French had advanced twenty miles, reaching the Aisne River.

The advance continued during the first eleven days of November. On 6 November the French Fourth Army and the US I corps were approaching Sedan, and the crucial Sedan-Metz railway line came under artillery fire, threatening a key German supply line. There was an element of confusion over which army would get the honour of capturing Sedan which saw the US 1st Division advance towards the city only to ordered to halt to allow the French to take the city, scene of a humiliating defeating during the Franco-Prussian War. The battle only ended with the final armistice, at 11.00 am on 11 November 1918.

The battle became known for the “lost battalion”. During the first phase of the battle, elements of two battalions from the 308th Infantry had become isolated in a steep sided gully between Bois d’Apremont and Charleveaux. The Germans held the ridgeline. From 2 October to 7 October the 650 men of the lost battalion held on against determined German attacks, suffering 450 casualties before they were finally relieved by the advancing 77th Division.

The battle was also noteworthy for the performance of three regiments from the American 93rd Division, manned by black soldiers. These regiments were operating with the French 161st Division, wore French uniforms and used French equipment. The US Army barely used its black regiments, having seemingly forgotten the lessons of the American Civil War where black soldiers had performed very well. In contrast the French had been using African troops throughout the war, and saw the 93rd Division as no different from other American troops. By 28 September all three regiments were heavily engaged in the fighting, taking part in the advance and capturing a series of villages. By the time they were relieved, the three regiments had suffered 2,246 casualties.

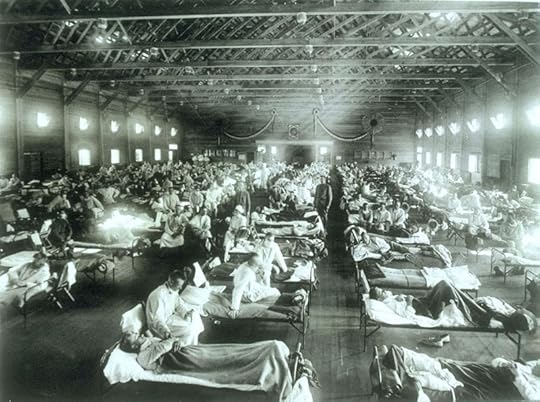

The Meuse-Argonne offensive cost the Americans 117,000 casualties, the French 70,000 and the Germans 100,000. The American casualties represented 40% of their total battlefield losses during the war. Amongst those losses were 48,909 dead. In a dreadful irony, the Spanish Influenza would eventually kill 53,000 American soldiers before the end of the war.

(Source: http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meuse-Ar...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American...

http://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries/cemete...

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/w...

http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/bigshow.htm

by

by

Edward G. Lengel

Edward G. Lengel by Robert H. Ferrell (no photo)

by Robert H. Ferrell (no photo) by William S. Triplet (no photo)

by William S. Triplet (no photo) by Paul F. Braim (no photo)

by Paul F. Braim (no photo) by Michael Clodfelter (no photo)

by Michael Clodfelter (no photo)

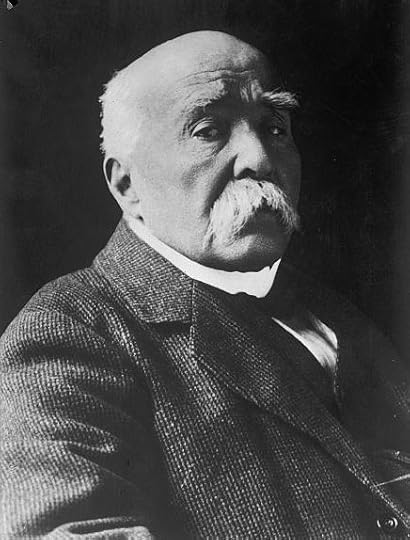

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau was born in Mouilleron-en-Pareds, France, on 28th September, 1841. His mother, Sophie Eucharie Gautreau (1817-1903) was from a Huguenot family. His father, Benjamin Clemenceau (1810-1897) was a supporter of the 1848 Revolution and this ensured he grew up with strong republican views.

With a group of fellow students Clemenceau began publishing Le Travail. It was seized by the police and Clemenceau spent 73 days in prison. On his release he started a new journal, Le Matin, but this also got him into trouble with the authorities.

After finishing his medical studies he went to live in New York. He was impressed by the political freedom enjoyed by the people of the United States and considered settling permanently in the country. He found work as a schoolteacher in Stamford, Connecticut and eventually married one of his former students.

Clemenceau returned home in 1869 and established himself as a doctor in Vendée. When Germany defeated France in 1870 Clemenceau moved to Paris and once again became involved in radical politics. In February, 1871, Clemenceau was elected as a Radical Republican deputy in the National Assembly. He voted against the peace terms demanded by Germany and became involved in the insurrection known as the Paris Commune. After being re-elected to the National Assembly in 1876, Clemenceau emerged as the leader of the Radical-Republicans. As a result of his aggressive debating style, Clemenceau was given the nickname, 'The Tiger'.

In 1902 Clemenceau became a senator and four years later, at the age of 61, was appointed minister of home affairs. Now a right-wing nationalist, Clemenceau ruthlessly suppressed popular strikes and demonstrations. Seven months later Clemenceau became France's prime minister. His period in office (1907-10) was marked by his hostility to socialists and trade unionists.

On the outbreak of the First World War Clemenceau refused office as justice minister under the French prime minister, Rene Viviani. As editor of L'Homme Libre, Clemenceau became an outspoken opponent of Joseph Joffre, chief of general staff in the French Army. Clemenceau also accused the interior minister, Louis Malvy, of being a pacifist when it became known that he favoured a negotiated peace.