The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Part I Chapters 09-10

Chapter 10 introduces a new character by the name of Stephen Blackpool, and that is why the chapter is entitled „Stephen Blackpool“. Stephen is a worker in Coketown, and workers are called “hands”, which in itself is a very telling synechdoche. The narrator says that Stephen is forty years old and then he does on, describing him as follows:

Chapter 10 introduces a new character by the name of Stephen Blackpool, and that is why the chapter is entitled „Stephen Blackpool“. Stephen is a worker in Coketown, and workers are called “hands”, which in itself is a very telling synechdoche. The narrator says that Stephen is forty years old and then he does on, describing him as follows:”Stephen looked older, but he had had a hard life. It is said that every life has its roses and thorns; there seemed, however, to have been a misadventure or mistake in Stephen’s case, whereby somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else’s thorns in addition to his own. He had known, to use his words, a peck of trouble. He was usually called Old Stephen, in a kind of rough homage to the fact.

A rather stooping man, with a knitted brow, a pondering expression of face, and a hard-looking head sufficiently capacious, on which his iron-grey hair lay long and thin, Old Stephen might have passed for a particularly intelligent man in his condition. Yet he was not. He took no place among those remarkable ‘Hands,’ who, piecing together their broken intervals of leisure through many years, had mastered difficult sciences, and acquired a knowledge of most unlikely things. He held no station among the Hands who could make speeches and carry on debates. Thousands of his compeers could talk much better than he, at any time. He was a good power-loom weaver, and a man of perfect integrity. What more he was, or what else he had in him, if anything, let him show for himself.”

What is this about Stephen’s not being good at making speeches and carrying on debates? And of his being a man of perfect integrity? Does this imply some criticism against trade unions? We will probably learn more in the course of the novel. At the moment, Stephen is waiting for a woman called Rachael. When he finally finds her, we get to know that she is about 35 years old, and then Stephen engages in a sort of talk that lead me to believe that he has a soft spot for Rachael and that Rachael also has one for Stephen, although she does not want him to walk her home too often because people already start talking about them. I found it quite difficult to make head or tail of their conversation and, to tell you the truth, I was rather put off by Stephen’s tendency to bemoan his fate. He may not be too good at making speeches, but he seems to have quite a lucky hand at making himself look like a piteous whinger.

When he has seen Rachael off, he goes to his own house, only to find there an unwelcome guest, whom he greets with the dismayed words, “Hast thou come back again!”

”Such a woman! A disabled, drunken creature, barely able to preserve her sitting posture by steadying herself with one begrimed hand on the floor, while the other was so purposeless in trying to push away her tangled hair from her face, that it only blinded her the more with the dirt upon it. A creature so foul to look at, in her tatters, stains and splashes, but so much fouler than that in her moral infamy, that it was a shameful thing even to see her.”

We don’t learn yet who this woman is, but she spitefully says that she has indeed come back and that she will do so again and again. She also tells Stephen to come away from the bed as she has a right to it – which made me conclude that this woman must be Stephen’s lawful wife.

Stephen's lodgings are so dank and dark, it is little wonder that his shoulders are stooped. Then add to the picture this decrepit, dirty, smelly woman and we have a cocktail for a truly depressing evening. Poor Stephen! He made a decision, probably in good faith, and now he has to pay for it forever, Amen. I so wanted him to get together with the girl that he loves, but Dickens won't give hand-outs easily. I must wait and hope and hope against hope.

Stephen's lodgings are so dank and dark, it is little wonder that his shoulders are stooped. Then add to the picture this decrepit, dirty, smelly woman and we have a cocktail for a truly depressing evening. Poor Stephen! He made a decision, probably in good faith, and now he has to pay for it forever, Amen. I so wanted him to get together with the girl that he loves, but Dickens won't give hand-outs easily. I must wait and hope and hope against hope.

There are many Dickens characters that have a special place in my mind and Sissy Jupe is one of them. How horrible to have a thirst for creativity and have that taken from you. The first sentence of chapter 9 "Sissy Jupe had not an easy time of it... " is a masterful understatement. The contrast between Sissy and Louisa is initially quite striking which suggests that one or the other will change before the end of the novel. That said, it is much too early for such an alteration in character. I wonder how much Dickens's original reading audience would have discussed the possible and potential plot and character twists yet to come. While the reading audience would have been familiar with the broad strokes of Dickens's style by this point in his career, they would also be wise enough to know that nothing is certain.

There are many Dickens characters that have a special place in my mind and Sissy Jupe is one of them. How horrible to have a thirst for creativity and have that taken from you. The first sentence of chapter 9 "Sissy Jupe had not an easy time of it... " is a masterful understatement. The contrast between Sissy and Louisa is initially quite striking which suggests that one or the other will change before the end of the novel. That said, it is much too early for such an alteration in character. I wonder how much Dickens's original reading audience would have discussed the possible and potential plot and character twists yet to come. While the reading audience would have been familiar with the broad strokes of Dickens's style by this point in his career, they would also be wise enough to know that nothing is certain.

Hilary wrote: "Stephen's lodgings are so dank and dark, it is little wonder that his shoulders are stooped. Then add to the picture this decrepit, dirty, smelly woman and we have a cocktail for a truly depressing..."

Hilary wrote: "Stephen's lodgings are so dank and dark, it is little wonder that his shoulders are stooped. Then add to the picture this decrepit, dirty, smelly woman and we have a cocktail for a truly depressing..."Ah, here is the Coketown of Hilary's fine alliteration. "Nature was as strongly bricked out as the killing gases were bricked in ... the whole an unnatural family, shouldering, and trampling, and pressing one another to death ... where the chimneys, for want of air ..."

When we comsider Stephen's last name there is yet another layer to the misery. "Black" Pool". What a perfect, yet tragically horrid name. The blackness of the town, the soot from the chimneys, the drabness of the walls, the people's homes, their very souls. And "pool." A place of gathering, a low-lying container. Because of the place and the word "black" an impression of a fetid hole.

Gradgrind, M'Choakumchild, Blackpool. Later in the novel it will be interesting to study further a person's first name as well. To date we have Cecelia, the patron saint of music (and thus suggestive of creation and beauty) for Sissy. Stephen ... Hmmm! :-)

Again, another mention of a grimy northern town - this time Blackpool. And again, on the wrong side of the Pennines. LOL.

Again, another mention of a grimy northern town - this time Blackpool. And again, on the wrong side of the Pennines. LOL. Blackpool, is one of those terrible seaside towns that you get dragged to when you're a kid, growing up in England. We have the English version of the Eiffel Tower there. I spent several holidays there and up 'the Tower' in the ballroom, watching my grandparents waltzing around the dance floor.

It's bittersweet - the tackiness and depressive atmosphere of the northern English holiday centre and the memories of my childhood and family.

Needless to say, the association of the name Blackpool with Dickens' character Blackpool, made me feel very sorry for this poor man, even before his story was revealed. I wonder if this was done on purpose. Eh, Mr Dickens?!

Kate wrote: "Just found this article - http://metro.co.uk/2016/01/31/this-is.... It says it all!"

Kate wrote: "Just found this article - http://metro.co.uk/2016/01/31/this-is.... It says it all!"Thanks Kate

What fantastic, or would that be fatalist, timing to have this article published as we are introduced to Stephen Blackpool.

Sorry to read about your memories of the place. Perhaps if Sleary's circus was in town during your early-day visits you'd have better memories.

I know where I won't be going if I ever visit England again.

Tristram wrote: They then talk about some of the mistaken answers Sissy has given to Mr. M’Choakumchild, and while her answers might not be particularly knowledgeable, yet they often have a ring of truth and wisdom in them, if you ask me. ."

Tristram wrote: They then talk about some of the mistaken answers Sissy has given to Mr. M’Choakumchild, and while her answers might not be particularly knowledgeable, yet they often have a ring of truth and wisdom in them, if you ask me. ."I think if you ask almost anybody, they would agree.

I suspect that Dickens had a great deal of fun with this conversation. But there is some real hidden wisdom underneath, which emphasizes the difference between information (facts) and knowledge. Sissy has few facts, but much knowledge.

Tristram wrote: "Tom is clearly developing into a selfish boy, "

Tristram wrote: "Tom is clearly developing into a selfish boy, "Tom reminds me a bit of John Reed in Jane Eyre.

Hilary wrote: "I so wanted him to get together with the girl that he loves, but Dickens won't give hand-outs easily. ."

Hilary wrote: "I so wanted him to get together with the girl that he loves, but Dickens won't give hand-outs easily. ."Excellently said.

Kate wrote: "Just found this article - http://metro.co.uk/2016/01/31/this-is.... It says it all!"

Kate wrote: "Just found this article - http://metro.co.uk/2016/01/31/this-is.... It says it all!"Ugh. That photo of the rain-soaked "beach" says it all. How can one NOT be depressed living in a place like that?

And it's the only town I know where "Seaside Way" is ten blocks or so away from the seaside on the wrong side of some quite ugly industrial buildings.

Awh, thank you so much, Everyman. That means a lot.

Awh, thank you so much, Everyman. That means a lot.Kate, the photo of BP is dire. I have never been, though we have friends who live there. One is, however, a blackpuddlian ?? (Fits with the picture!). He thinks that it's the best thing since sliced bread. Well, I guess it's his hometown and he knows no better! :p

And here is an illustration for Chapter 9 by Harry French:

And here is an illustration for Chapter 9 by Harry French:

"It Would Be A Fine Thing To Be You, Miss Louisa!"

Chapter 9

Harry French

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition 1875

I can't say I agree with her statement, by the way.

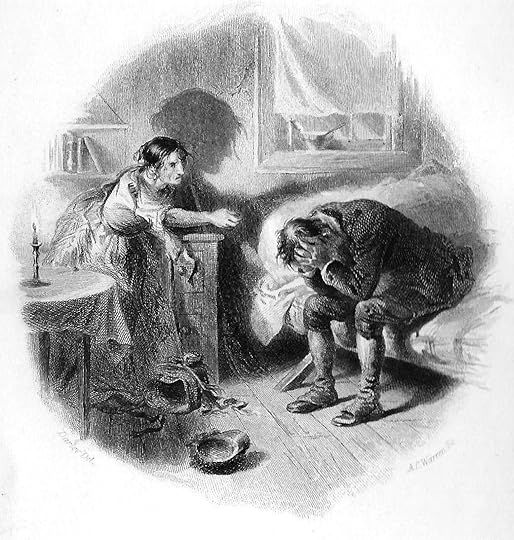

Here is another illustration by Harry French, this time for Chapter 10:

Here is another illustration by Harry French, this time for Chapter 10:

"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'"

Chapter 10

Harry French

Illustration for Dicken's "Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition 1870's

Commentary:

"The high factory chimneys fed by the industrial furnaces of Dickens's Coketown cast no shadows throughout Harry French's programme of twenty illustrations for the British Household Edition of Hard Times. Even Stephen Blackpool's "disabled, drunken" wife seems to have been filtered by French's essentially middle-class pictorial imagination, so that her hair is scarcely "tangled" and her dress hardly the "tatters" that Dickens specifies in his description of a woman reduced to level of a "creature" through substance abuse and addiction. However, Stephen's beard, top hat, and tail-coat are plausible, given the historical context in which the artist drew them. Even the working class attempted to maintain a respectable appearance by shopping in second-hand clothing shops, acquiring what had been some seasons previous fashionable and what still had considerable wear left; we note that Stephen's coat seems somewhat out-of-date compared to the fuller frock-coats worn by Gradgrind and Bounderby.

Stephen's beard (purely the artist's invention) may reflect the style that came in after the Crimean War, when non-military gentlemen of fashion attempted to emulate the military beard: "As to whiskers, men were usually clean-shaven until the 1850s, when the soldiers returned from the Crimean War with beards. . . . . Soon, however, every respectable man sprouted one". With respect to both beards and clothing, the lower classes usually attempted to follow the fashions set by the upper and then the upper-middle classes."

I don't know, he looks like the captain of a ship to me.

This is what C. S. Reinhart thought of the same scene:

This is what C. S. Reinhart thought of the same scene:

[image error]

Chapter 10

C. S. Reinhart

Illustration for Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

Commentary:

"Having bidden his friend Rachael goodnight after their day at the factory, Stephen, his cap still on, enters his room above a little shop and lights a candle to discover that his slatternly wife, an opium addict and alcoholic, has returned. Significantly, in the text he "stumbles" against her (presumably she is on the floor), for she is the stumbling block to his relationship with Rachael and to his having a normal family life. Normally, the eye first moves towards the principal figures in an illustration and then notes the background details, but here Reinhart has focused our attention on the bureau with its lion's-paw legs, to which we are introduced simultaneously through the letter-press at the top of the page and in the plate. In contrast to the room at The Pegusus's Arms in the previous illustration, this room has been personalised with books and papers on a desk in the corner of the room (right), ands is lit by a fireplace (left). "A few books and writings were on an old bureau in a corner, the furniture was decent and sufficient" (Ch. 10). These personal objects, however, Reinhart has but sketchily shown (and omitted entirely the three-legged table beside which Mrs. Blackpool has fallen) because his emphasis is on the figures of the honest mechanic, candle held in his upstage (left) hand, and his quasi-human wife, steadying herself with her left hand as she pushes the tangled hair from her face with her right (upstage) hand, as in the letter-press. Though her face in plate 4 is "stolid and drowsy" (Ch. 10) as Dickens remarks, we have no sense of her swaying to and fro, nor of her gesticulating. The moral infamy with which Dickens invests her we intuit from her general blackness, her cat-like face hidden behind a veil of uncombed hair, and the claw-like left hand which echoes the claw-like foot of the bureau.

Reinhart's own background is worth noting in connection with his sympathetic treatment of Stephen Blackpool, for as a young man in his native Pittsburgh he was employed in railway work and at a steel factory, before he left America to study art in Paris and Munich. "

When I first saw the illustration I thought for a minute he was holding a gun and was about to shoot her, or already had.

Sol Eytinge also did an illustration for Chapter 10, this one titled "Stephen and Rachael".

Sol Eytinge also did an illustration for Chapter 10, this one titled "Stephen and Rachael".

Commentary:

Eytinge has chosen to realize that tender, initial meeting of the middle-aged factory-workers in the street outside the mill (left) just after late-afternoon shift-change. Eytinge appropriately shows Rachael as still attractive, despite the severity of factory work, and Stephen as prematurely grey, careworn, and almost numb, standing in the rain after hours of service to the implacable machine, driven by steam engines whose nine chimneys dominate the backdrop.

C. S. Reinhart would later introduce Stephen in the context of his marital difficulties in "Heaven's Mercy, Woman! . . . . Hast Thou Come Back Again!", shocking the reader with the animalistic woman who repeatedly despoils him; although his view of the same moment is less graphic, Harry French again references Stephen's unfortunate domestic circumstances and his victimization by his wife in "'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'" The passage of description that Eytinge is realizing in the cloth-capped figure of Stephen occurs much earlier, in chapter 10:

". . . in the last close nook of this great exhausted receiver, where the chimneys, for want of air to make a draught, were built in an immense variety of stunted and crooked shapes, as though every house put out a sign of the kind of people who might be expected to be born in it; among the multitude of Coketown, generically called "the Hands," — a race who would have found mere favour with some people, if Providence had seen fit to make them only hands, or, like the lower creatures of the seashore, only hands and stomachs — lived a certain Stephen Blackpool, forty years of age.

Stephen looked older, but he had had a hard life. It is said that every life has its roses and thorns; there seemed, however, to have been a misadventure or mistake in Stephen's case, whereby somebody else had become possessed of his roses, and he had become possessed of the same somebody else's thorns in addition to his own.

He had known, to use his words, a peck of trouble. He was usually called Old Stephen, in a kind of rough homage to the fact. A rather stooping man, with a knitted brow, a pondering expression of face, and a hard-looking head sufficiently capacious, on which his iron-grey hair lay long and thin, Old Stephen might have passed for a particularly intelligent man in his condition. Yet he was not. He took no place among those remarkable "Hands," who, piecing together their broken intervals of leisure through many years, had mastered difficult sciences, and acquired a knowledge of most unlikely things. He held no station among the Hands who could make speeches and carry on debates. Thousands of his compeers could talk much better than he, at any time. He was a good power-loom weaver, and a man of perfect integrity. What more he was, or what else he had in him, if anything, let him show for himself."

However, Eytinge has chosen not merely to realize Dickens's description of Old Stephen but also to capture the moment at which he is relieved to catch Rachael in the street:

"But, he had not gone the length of three streets, when he saw another of the shawled figures in advance of him, at which he looked so keenly that perhaps its mere shadow indistinctly reflected on the wet pavement, — if he could have seen it without the figure itself moving along from lamp to lamp, brightening and fading as it went, — would have been enough to tell him who was there. Making his pace at once much quicker and much softer, he darted on until he was very near this figure, then fell into his former walk, and called "Rachael!"

She turned, being then in the brightness of a lamp; and raising her hood a little, showed a quiet oval face, dark and rather delicate, irradiated by a pair of very gentle eyes, and further set off by the perfect order of her shining black hair. It was not a face in its first bloom; she was a woman five-and-thirty years of age."

This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:

This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:

"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley

For Dickens's Hard Times, Household Edition (1862)

Passage Illustrated

"Heaven's mercy, woman!" he cried, falling farther off from the figure. "Hast thou come back again!"

Such a woman! A disabled, drunken creature, barely able to preserve her sitting posture by steadying herself with one begrimed hand on the floor, while the other was so purposeless in trying to push away her tangled hair from her face, that it only blinded her the more with the dirt upon it. A creature so foul to look at, in her tatters, stains and splashes, but so much fouler than that in her moral infamy, that it was a shameful thing even to see her.

After an impatient oath or two, and some stupid clawing of herself with the hand not necessary to her support, she got her hair away from her eyes sufficiently to obtain a sight of him. Then she sat swaying her body to and fro, and making gestures with her unnerved arm, which seemed intended as the accompaniment to a fit of laughter, though her face was stolid and drowsy.

"Eigh, lad? What, yo'r there?" Some hoarse sounds meant for this, came mockingly out of her at last; and her head dropped forward on her breast.

"Back agen?" she screeched, after some minutes, as if he had that moment said it. "Yes! And back agen. Back agen ever and ever so often. Back? Yes, back. Why not?"

Roused by the unmeaning violence with which she cried it out, she scrambled up, and stood supporting herself with her shoulders against the wall; dangling in one hand by the string, a dunghill-fragment of a bonnet, and trying to look scornfully at him.

"I'll sell thee off again, and I'll sell thee off again, and I'll sell thee off a score of times!" she cried, with something between a furious menace and an effort at a defiant dance. "Come awa' from th' bed!" He was sitting on the side of it, with his face hidden in his hands. "Come awa' from 't. 'Tis mine, and I've a right to 't!"

Commentary

"The scenes of life in an industrial town in the original 1854 weekly serial are based on Dickens's observations during the Preston Strike in the North of England, a few days' experiences transformed into Hard Times For These Times. The fortunes of a secondary character in the novel, the archetypal working man saddled with an alcohol-and-laudanum addicted wife (left), as the subject for his initial illustration demonstrates Darley's understanding of the "industrial" nature of the story.

Darley's dramatic study of the long-suffering Stephen and his incubus is not based on earlier illustrations, since no illustrated edition of the 1854 novel, serialized in Household Words existed at the time that James G. Gregory, the New York publisher, commissioned Felix Octavius Carr Darley to provide the frontispieces for the majority of the fifty-five volumes in the so-called "Household Edition," which his firm began to publish in 1861, six years prior to the Ticknor-Fields Diamond Edition, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr., and seven years prior to the Chapman and Hall Illustrated Library Edition, with its elegant but slight series of illustrations by Fred Walker. In fact, this Darley photogravure, with the ominous shadow of Mrs. Blackpool dominating the room, anticipates realizations of that same relationship by Fred Walker, C. S. Rinehart, and Harry French. The spartan, orderly room of the working-class hero of the novel, with the few books representing his attempts at self-education and self-help, contrasts the chaotic misery that the slatternly wife (left) without a Christian name inflicts upon the prostrate Stephen (right), whose despair Darley masterfully conveys through Stephen's posture.

The other properties — the "writings . . . on an old bureau in the corner," the candle on the three-legged table, the bare floorboards, and the few sticks of furniture — come directly from the text; to these Darley has significantly added the wife's bonnet and Stephen's cap on the floor. However, the effeciveness of the illustration depends upon the menacing shadow of Mrs. Blackpool's arm that extents her own reach right across the despairing Stephen and, as it were, into his future as she threatens to pawn his belongings again and again so that she can procure alcohol and opium."

Thanks for these, Kim. Some very interesting illustrations and what talent! I think I like Darley's best. :-)

Thanks for these, Kim. Some very interesting illustrations and what talent! I think I like Darley's best. :-)

Kim wrote: "Here is another illustration by Harry French, this time for Chapter 10:

Kim wrote: "Here is another illustration by Harry French, this time for Chapter 10:"'Heaven's Mercy, Woman!' He Cried, Falling Farther Off From The Figure. 'Has Thou Come Back Agen?'"

Chapter 10

Harry Fren..."

French's house does look rather prosperous.

Kim wrote: "Sol Eytinge also did an illustration for Chapter 10, this one titled "Stephen and Rachael".

Kim wrote: "Sol Eytinge also did an illustration for Chapter 10, this one titled "Stephen and Rachael".Commentary:

Eytinge has chosen to realize that tender, initial meeting of the middle-aged factory-wor..."

This is a powerful illustration and the image is suitably blurry. The soot, the rain, the sadness, the eerie feeling that these people are ghosts within their own lives and city are all suggested. Great illustration.

Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:

Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley

The Darley illustration is also powerful, and as the commentary says the huge misshapen shadow of Stephen's wife that appears on the wall and hovers over him is very powerful.

Kim. Once again, a tip of my hat. By the way, are you dug out of all that snow yet?

P.P. Forgive the italics. I have no idea what I did, but obviously did something.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:My snow is, sadly, melting. One reason it is sad is the obvious one in that soon if this keeps going I won't have any more snow in my yard, we still have about 8 inches right now. The other reason is that all this melting is making the ground very, very muddy and there are trails of mud all through my house. If it isn't my husband or son coming home from work with muddy shoes on, it certainly is Willow going out to the backyard whenever she wants to all day long. There are paw prints from the back door all through the house.

Kim wrote: "Poor Blackpool! It's cute, at least it is in old pictures!

Kim wrote: "Poor Blackpool! It's cute, at least it is in old pictures!"

That's no difficult thing! Even I am cute in my old, some of my very old pictures!

A great range of illustrations! Thanks for collecting them and posting them, Kim!

A great range of illustrations! Thanks for collecting them and posting them, Kim!I, like Hilary, like Darley's illustration best because it picks the moment when Stephen has sat down on the bed, thus dimishing the difference in height between himself and his wife, which must make the latter become more menacing than as if she were still lying on the floor. As an enthusiast of film noir, I also particularly like the shadow on the wall, which shows that indeed Stephen will not find it very easy to get rid of his wife, whom he may have chosen in an ill-starred moment of his life.

I like Reinhart's illustration second-best because it also - unlike French's - shows the misery of Stephen Blackpool's situation, and the haunting quality of his wife.

In Eytinge's illustration, I think I see too much idealization of the two characters. They look too much like patient and noble martyrs and too little like careworn, real-life workers to me. At least, this time, Dickens has chosen to endow Rachael with a dialect instead of having her speak flawless English like Little Nell.

Awh no, Kim, not your snow! I was enjoying it vicariously as we only had a sort of white frost, mascarading as snow. Well, we may have had a little snow one day; disappeared by the evening. :-(.

Awh no, Kim, not your snow! I was enjoying it vicariously as we only had a sort of white frost, mascarading as snow. Well, we may have had a little snow one day; disappeared by the evening. :-(.

Tristram wrote: "Kim wrote: "Poor Blackpool! It's cute, at least it is in old pictures!

Tristram wrote: "Kim wrote: "Poor Blackpool! It's cute, at least it is in old pictures!"

That's no difficult thing! Even I am cute in my old, some of my very old pictures!"

Prove it.

Tristram wrote; Even I am cute in my old, some of my very old pictures!"

Tristram wrote; Even I am cute in my old, some of my very old pictures!"Kim wrote: ...

Prove it."

The baby on the bear rug photo???

For me, Sissy's schooling in Chapter 9 depicts the head vs. heart conflict. Oddly, reading this chapter I had a flashback to Star Trek -- Spock's last words, after he sacrifices himself for the sake of the crew: ''The good of the many, outweighs the good of the few." Apparently, his dying words are based on 19th C English philosopher John Stuart Mill's utilitarian theory. (The paths Dickens leads to…) Although destitute of facts, Sissy has empathy for the few who starve or drown ( I wondered if the question about drowning on long voyages was a justification of colonialism). I think Sissy's compassion has developed not only from her circus family, but by her love of reading stories. I particularly liked that, by hearing Sissy's story, Louisa gains compassion for her -- nicely shown in her reaction when Sissy receives no letters.

For me, Sissy's schooling in Chapter 9 depicts the head vs. heart conflict. Oddly, reading this chapter I had a flashback to Star Trek -- Spock's last words, after he sacrifices himself for the sake of the crew: ''The good of the many, outweighs the good of the few." Apparently, his dying words are based on 19th C English philosopher John Stuart Mill's utilitarian theory. (The paths Dickens leads to…) Although destitute of facts, Sissy has empathy for the few who starve or drown ( I wondered if the question about drowning on long voyages was a justification of colonialism). I think Sissy's compassion has developed not only from her circus family, but by her love of reading stories. I particularly liked that, by hearing Sissy's story, Louisa gains compassion for her -- nicely shown in her reaction when Sissy receives no letters.

What struck me about Stephen and Rachael's brief meeting, was that it would have been the highlight of his day, for probably the last 20 years. Not much to sustain himself with. I'm curious about her anxiety when he complains about the law -- does she worry he will take matters into his own hands?

What struck me about Stephen and Rachael's brief meeting, was that it would have been the highlight of his day, for probably the last 20 years. Not much to sustain himself with. I'm curious about her anxiety when he complains about the law -- does she worry he will take matters into his own hands? The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch.

Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:

Kim wrote: "This is an illustration for Chapter 10 by Felix O. C. Darley:"Stephen Blackpool"

Chapter 10

F.O.C. Darley ..."

Thanks for these illustrations, Kim. I think this one really conveys Stephen's desperation.

I'm puzzled by how the commentators know that Mrs. Blackpool is an opium addict. Because it is common, or did I miss something?

Vanessa wrote: "For me, Sissy's schooling in Chapter 9 depicts the head vs. heart conflict. Oddly, reading this chapter I had a flashback to Star Trek -- Spock's last words, after he sacrifices himself for the sak..."

Vanessa wrote: "For me, Sissy's schooling in Chapter 9 depicts the head vs. heart conflict. Oddly, reading this chapter I had a flashback to Star Trek -- Spock's last words, after he sacrifices himself for the sak..."Hi Vanessa

I think there is little question that Dickens was aiming his pen directly at the utilitarian fervour of the times. Two of Gradgrind's children were named Malthus and Adam Smith. Thank you for making the celestial leap to Spock's death. Great. I never though about Spock's last words.

The ladders were grimly fascinating, weren't they? As for Rachael's concern for Stephen, could it be that Dickens is setting up the devil-angel contrast between women in Stephen's life?

Everyman wrote: "The baby on the bear rug photo???"

Everyman wrote: "The baby on the bear rug photo???"I can't serve with one of those because our family was so poor they had to give me into a foster bear family, where I had to draw the bees on myself while they were enjoying all the honey. They would not have liked me, however, to sit on a bear's skin.

Interesting that you came to think of "The good of the many outweighs the good of the few" because it is this utilitarian way of thinking that is implicit in M'Choakumchild's lessons if I understand them correctly: He says that a commonwealth in which only 1% of the people suffer is a good commonwealth, while Sissy counters that it is not a good one for those 1%. She simply objects to losing a view the individual's sufferings over statistics that may obfuscate it. She has too much pity with the individual to be a Mills adept ;-)

Interesting that you came to think of "The good of the many outweighs the good of the few" because it is this utilitarian way of thinking that is implicit in M'Choakumchild's lessons if I understand them correctly: He says that a commonwealth in which only 1% of the people suffer is a good commonwealth, while Sissy counters that it is not a good one for those 1%. She simply objects to losing a view the individual's sufferings over statistics that may obfuscate it. She has too much pity with the individual to be a Mills adept ;-)As to Mrs. Blackpool, I took her to be a drunkard because she is introduced with the following words: "A disabled, drunken creature, barely able to preserve her sitting posture by steadying herself with one begrimed hand on the floor, while the other was so purposeless in trying to push away her tangled hair from her face, that it only blinded her the more with the dirt upon it." Maybe, in a later part of the novel an addiction to opium will be mentioned but at the present moment of time I don't think we are given any hints in this direction.

Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch. ."

Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch. ."And yet very realistic. Have you ever been in an old English row house in the northern cities? I saw a few when I was in Liverpool, and the stairs are often so narrow and winding that you could never get a coffin up or down them. That's why, I think, the beds were all made to take apart, and the wardrobes were generally built in and not a separate piece of furniture you would have had to carry up and down stairs.

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "The baby on the bear rug photo???"

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "The baby on the bear rug photo???"I can't serve with one of those because our family was so poor they had to give me into a foster bear family, where I had to draw the bees on my..."

I suppose you were doing all this drawing while gnawing on chicken bones waiting for your cold gruel to get warm while walking three miles to school uphill through the snow. Did I get it all?

Kim wrote: "Did I get it all? "

Kim wrote: "Did I get it all? "By no means. You left out that he was barefoot, that although it was snowing his coat had been sold to buy coal so he had nothing but his shirt to ward off the snow, that he was required to beg for alms from every passerby, and that he was beaten at school because he didn't have his Latin translation done because his mother had had to use the last sheet of paper in the house to start the kitchen fire, and that because of being beaten he was crying on the way home and his tears froze on his face so he had an ice face by the time he got home to where he had to break the ice in his basin to wash his face before getting into the bved he shared with three brothers with only a sheet for a blanket.

There's more, but those I think are the most important elements you left out.

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Did I get it all? "

Everyman wrote: "Kim wrote: "Did I get it all? "By no means. You left out that he was barefoot, that although it was snowing his coat had been sold to buy coal so he had nothing but his shirt to ward off the snow..."

By the time I got to the Latin translation I was laughing out loud which made my husband and son who are trying to watch the Maryland-Nebraska college basketball game, both look at me like I was crazy. Again.

Peter wrote: "Two of Gradgrind's children were named Malthus and Adam Smith. Thank you for making the celestial leap to Spock's death...."

Peter wrote: "Two of Gradgrind's children were named Malthus and Adam Smith. Thank you for making the celestial leap to Spock's death...."Peter, it seemed light years apart, but apparently the 19th century influence reached far into the future...! Yes, in the quick look I had into Mill, I noticed he was a cohort of Malthus.

As for Rachael's concern for Stephen, could it be that Dickens is setting up the devil-angel contrast between women in Stephen's life?

I expect you're right. And isn't Rachael a biblical name -- the favourite/second wife of Jacob?

Tristram wrote: "As to Mrs. Blackpool, I took her to be a drunkard because she is introduced with the following words: "A disabled, drunken creature ..."

Tristram wrote: "As to Mrs. Blackpool, I took her to be a drunkard because she is introduced with the following words: "A disabled, drunken creature ..."I understood the same, Tristram, and expect we haven't seen the last of her...

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch. ."

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch. ."And yet very realistic. Have you ever been in an old English row house in the northern cities? I sa..."

Yes, the narrow streets and alleys in York stand out, but it's been many years. I imagine navigating narrow staircases and passages with a coffin could become morbidly funny.

Vanessa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Two of Gradgrind's children were named Malthus and Adam Smith. Thank you for making the celestial leap to Spock's death...."

Vanessa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Two of Gradgrind's children were named Malthus and Adam Smith. Thank you for making the celestial leap to Spock's death...."Peter, it seemed light years apart, but apparently the 19..."

Vanessa. With all the great surnames that Dickens has in HT I think the first names may well yield some interesting connections as well. Cecilia (Sissy) we have already speculated upon. Rachael, Stephen and others have connections to the Bible. Perhaps as we read further into the novel they will reveal themselves more.

I have little to add, as you all have already made so many astute observations. My only contribution is to wonder how Blackpool, Rachael, and the woman we assume is Mrs. Blackpool will intersect with Sissy, Gradgrind, et al. As someone said earlier, as Dickens fans we know him well enough to be sure that their stories will all come together somehow, and I can't wait to see how he brings it about.

I have little to add, as you all have already made so many astute observations. My only contribution is to wonder how Blackpool, Rachael, and the woman we assume is Mrs. Blackpool will intersect with Sissy, Gradgrind, et al. As someone said earlier, as Dickens fans we know him well enough to be sure that their stories will all come together somehow, and I can't wait to see how he brings it about. PS I was very distraught to read about the abuse that poor, sweet Merrylegs had to suffer. It made me much less sympathetic towards Mr. Jupe.

Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch."

Vanessa wrote: "The detail about the undertaker's black ladder was a particularly grim touch."Foreshadowing, perhaps?

Tristram wrote: "The good of the many outweighs the good of the few"

Tristram wrote: "The good of the many outweighs the good of the few"But perhaps in this case, it should be "the bad of the many outweighs the good of the few"?

Everyman wrote: "Have you ever been in an old English row house in the northern cities?"

Everyman wrote: "Have you ever been in an old English row house in the northern cities?"There are plenty of them and still are. These terraced houses were often purpose built for workers during the industrial revolution. Some are so small, we call them (at least in Yorkshire), "two up, two down" and/or "back to back". The "two up, two down" refers to there being four rooms on each floor, with the staircase in the room. So there would be a cellar/basement, ground floor (street level), first and second floor. If you happened to live in a "two up, two down" that is also a "back to back" then there are no back windows because you are backing onto another terrace house. In fact, you're blocked in on three sides. My cousin lived in one for a while and it was rather grim and depressing. I felt rather claustrophobic, being in that house.

Vanessa wrote: "the narrow streets and alleys in York stand out"

Vanessa wrote: "the narrow streets and alleys in York stand out"The Medieval rows in York are very different from the Industrial terraces, although the streets are very narrow in both. I'll have to find some links to some good examples...

Also, I should add, that I think Dickens is getting a big carried away with mixing characteristics of London with the newer northern cities. I've posted a link in my next post. If you have a look, you'll see that they don't have the Dickensian London 'feel' about them.

Here is a link to what the inside and outside of terrace houses from the Industrial era looked like, albeit from disturbing pictures of the 1970s. However, I can only imagine they looked similar or worse, a century earlier.

Here is a link to what the inside and outside of terrace houses from the Industrial era looked like, albeit from disturbing pictures of the 1970s. However, I can only imagine they looked similar or worse, a century earlier.http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/artic...

FYI, the last picture, with the terraces that have "Beecham's" advertised on the end wall, is from my home city. From what I recognise, it's from the area my Grandfather was born. These are your typical "back to back" houses. Interesting but extremely depressing, no matter what era. I can promise you there still isn't much change. Several years ago, before he died, I took my Grandfather to find the home where he was born. It just looked like that picture, but with massive iron gates on the ends of each row. The area is infamous for its crime.

we are moving on, slowly but constantly and maybe our progress into the novel is still a lot quicker than “Sissy’s Progress”, which is what this week’s first chapter is called. The narrator tells us of Sissy’s new life, which is very hard between Mr. M’Choakumchild on the one hand and Mrs. Gradgrind on the other, and the constant hail of facts. More than once Sissy would have run away, were it not for the thought of her father, her certainty of his coming back and of his being happy to find her where he put her.

At school, Sissy is not particularly successful at all, which induces Mr. Gradgrind to keep her to it, thus making her more dejected but little wiser. One day, a conversation takes place between Sissy and Louisa, which is – in a way – unusual since Sissy and the Gradgrind children have generally been kept apart with a view to Sissy’s prior career. In their conversation, Sissy admits that she would like to be Louisa because in that case she would know a great deal more. Louisa replies that she might not be the better for all that knowledge and implies that she might even be the worse. She then says,

”’You are more useful to my mother, and more pleasant with her than I can ever be,’ Louisa resumed. ‘You are pleasanter to yourself, than I am to myself.’”

They then talk about some of the mistaken answers Sissy has given to Mr. M’Choakumchild, and while her answers might not be particularly knowledgeable, yet they often have a ring of truth and wisdom in them, if you ask me. I’ll give one bit of their conversation to let it stand for itself:

”‘National Prosperity. And he said, Now, this schoolroom is a Nation. And in this nation, there are fifty millions of money. Isn’t this a prosperous nation? Girl number twenty, isn’t this a prosperous nation, and a’n’t you in a thriving state?’

‘What did you say?’ asked Louisa.

‘Miss Louisa, I said I didn’t know. I thought I couldn’t know whether it was a prosperous nation or not, and whether I was in a thriving state or not, unless I knew who had got the money, and whether any of it was mine. But that had nothing to do with it. It was not in the figures at all,’ said Sissy, wiping her eyes.

‘That was a great mistake of yours,’ observed Louisa.

‘Yes, Miss Louisa, I know it was, now. Then Mr. M’Choakumchild said he would try me again. And he said, This schoolroom is an immense town, and in it there are a million of inhabitants, and only five-and-twenty are starved to death in the streets, in the course of a year. What is your remark on that proportion? And my remark was—for I couldn’t think of a better one—that I thought it must be just as hard upon those who were starved, whether the others were a million, or a million million. And that was wrong, too.’”

In the same vein, also Sissy’s employing the word “stuttering” for “statistics” made me wonder whether she is not much wiser than Mr. M’Choakumchild would ever dream of. The two girls also talk about Sissy’s father, and what we get to know of Mr. Jupe makes his decision to leave Sissy more believable to me. Apparently, he is a man given to depression and despair, and when it became clear to him that he would no longer be successful as a clown, he took to weeping. He even beat Merrylegs in a fit of despair when the dog would not do his tricks one night. While Sissy is telling this moving story – which finishes with an account of the day she saw her father the last time –, young Thomas Gradgrind comes in and, without really paying any heed to Sissy, urges Louisa to come into the drawing-room with him for Mr. Bounderby is there and – as Tom says – if Louisa is there, there will be a good chance of Bounderby’s asking Tom for dinner.

Tom is clearly developing into a selfish boy, who is willing to pawn his sister to Bounderby just because this might be of advantage to him. This already becomes clear in the following sentence:

”Here Tom came lounging in, and stared at the two with a coolness not particularly savouring of interest in anything but himself, and not much of that at present.”

It remains to be seen how he will behave if his sister might be forced to marry Bounderby.