The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

Hard Times

Hard Times

>

Part III Chapters 06 - 09

The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been speaking with the moribund Stephen, Sissy clandestinely gave Tom fair warning that it might be better to leave right now – a hint that the young man readily takes up. Sissy also told him, as we later learn, that he should take hiding in Mr. Sleary’s circus, which Sissy knows to be in the vicinity (Liverpool).

The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been speaking with the moribund Stephen, Sissy clandestinely gave Tom fair warning that it might be better to leave right now – a hint that the young man readily takes up. Sissy also told him, as we later learn, that he should take hiding in Mr. Sleary’s circus, which Sissy knows to be in the vicinity (Liverpool).Mr. Gradgrind is glad that for the moment his son is out of the way but also worried as to getting him out of the country in time. He has become quite a different, a meeker man, all in all, as the text points out:

”Aged and bent he looked, and quite bowed down; and yet he looked a wiser man, and a better man, than in the days when in this life he wanted nothing—but Facts.”

It also finally dawns upon him what Sissy has done for him and his family. Not only did she befriend Louisa and Mrs. Gradgrind and made Jane quite a different girl from what Louisa was at her age, but she also provided a hiding-place for Tom. In the text it says:

”He raised his eyes to where she stood, like a good fairy in his house, and said in a tone of softened gratitude and grateful kindness, ‘It is always you, my child!’”

Gradgrind and Louisa and Sissy set out for Sleary’s circus, the latter two directly, the former in a more roundabout way in order to distracts potential pursuers, and – to cut a long story short – they find young Tom in the guise of a black servant. It is, in a way, quite ironic that Gradgrind’s son should be saved by those whom Old Gradgrind used to despise as being useless and even detrimental to common sense. It is also quite ludicrous that Tom had to dress up as a kind of clown, in moth-eaten and shabby clothes, and with black dye in his face – this is, after all, what a child brought up according to the Gradgrind system looks like in the end. Tom confesses to his crime and tells his father how he had committed it and how he used the opportunity chance gave him to pin the crime on Blackpool. All the while, he utterly ignores Louisa.

Sleary has already worked out a plan of how to get Tom safely out of the country when suddenly Bitzer arrives on the scene, out of breath with running:

”There he stood, panting and heaving, as if he had never stopped since the night, now long ago, when he had run them down before.”

He instantly collars Tom, like Mrs. Sparsit had collared Mrs. Pegler some chapters before. Let’s see if he is more lucky than his companion at the bank. But in order to do this …

… we must turn over to another chapter, namely Chapter 8, which declares to become quite “Philosophical“. And it really does so in two ways.

… we must turn over to another chapter, namely Chapter 8, which declares to become quite “Philosophical“. And it really does so in two ways.The first kind of philosophy we get is Mr. Gradgrind’s utilitarian brew, which appears in a rather vulgarized form in Bitzer – but probably so because that was the way that it was ladled out to the pupils at Gradgrind’s school. Here are some example of this kind of vulgar utilitarianism and of how Mr. Gradgrind, quite belatedly, is made to taste his own stale medicine:

”‘Bitzer,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, broken down, and miserably submissive to him, ‘have you a heart?’

‘The circulation, sir,’ returned Bitzer, smiling at the oddity of the question, ‘couldn’t be carried on without one. No man, sir, acquainted with the facts established by Harvey relating to the circulation of the blood, can doubt that I have a heart.’

‘Is it accessible,’ cried Mr. Gradgrind, ‘to any compassionate influence?’

‘It is accessible to Reason, sir,’ returned the excellent young man. ‘And to nothing else.’“

A few seconds later, Bitzer explains to Mr. Gradgrind how his interests undubitably lie with Mr. Bounderby and how they were saved best by bringing Tom to heel and delivering him up to Mr. Bounderby. He then resumes:

”‘I beg your pardon for interrupting you, sir,’ returned Bitzer; ‘but I am sure you know that the whole social system is a question of self-interest. What you must always appeal to, is a person’s self-interest. It’s your only hold. We are so constituted. I was brought up in that catechism when I was very young, sir, as you are aware.’”

Mr. Gradgrind now at the very latest must realize what his teachings amount to, and the narrator bitterly adds, as though to mock the schoolmaster:

”It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for. Nobody was ever on any account to give anybody anything, or render anybody help without purchase. Gratitude was to be abolished, and the virtues springing from it were not to be. Every inch of the existence of mankind, from birth to death, was to be a bargain across a counter. And if we didn’t get to Heaven that way, it was not a politico-economical place, and we had no business there.”

Of all people, however, it is none other but Mr. Sleary – whom the former Mr. Gradgrind would merely have despised – who saves the day. He feigns to being brought round to Bitzer’s point of view and offers Bitzer a coach to avoid public notice – but at the same time he has concocted a trick to get one over on Bitzer and to help Tom escape. The exact details of the plan and its execution can be read in Chapter 8.

Sleary later tells Mr. Gradgrind that not long ago, when they were performing in Chester, a dog came to him whom he recognized as Merrylegs. The dog was quite exhausted and died on the spot, and the appearance of this dog can be seen as a sign of Sissy’s father having died, too, for the dog would never have abandoned its master. Sleary also gives Mr. Gradgrind another bit of philosophy, something more Epicurean in a way:

“’[…] Don’t be croth with uth poor vagabondth. People mutht be amuthed. They can’t be alwayth a learning, nor yet they can’t be alwayth a working, they an’t made for it. […]’”

And here we are in the last Chapter of the book, which is called “Final” and which Dickens uses to give us some information on what befell his major characters.

And here we are in the last Chapter of the book, which is called “Final” and which Dickens uses to give us some information on what befell his major characters.We learn that Mr. Bounderby gets rid of Mrs. Sparsit because he thinks that dismissing her from his household is the highest form of personal gratification he can get from her after all that has happened. There is a very funny altercation between the bully and the griffin, and at the end the griffin will go back into a much more modest and meanly life, with Lady Scadgers, with whom she will fight an endless battle. We also learn that Bitzer will rise in the firm, but that five years later, Mr. Bounderby will die of a stroke and leave a will that will cause a lot of litigation and ill-will. Strangely enough, we do not learn anything about Mrs. Pegler anymore.

Of Louisa we learn that she will never re-marry but be a good friend to Sissy and her family. Mr. Gradgrind will live on according to his newly-learned principles, and Tom, in his exile abroad, will quickly come to regret his base and thankless behaviour to his sister – just as Louisa anticipated – but death will put an end to his plans to pay her a visit.

Of Rachael we learn that after a long illness she resumes to her old life of factory work and that she even does acts of kindness to Stephen’s alcoholic wife, who is generally despised. Her life is hard and full of work, but she is content to do her work and prefers to do it “as her natural lot”.

Tristram wrote: "It also finally dawns upon him what Sissy has done for him and his family."

Tristram wrote: "It also finally dawns upon him what Sissy has done for him and his family."Well, one thing she's done is be accessory to a felony, to assist a fugitive to escape. For which she could have been, and might well have been if caught, sent to a long prison term, if not transported to Australia. That's quite a major thing to do for a family!

Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."

Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."Except that he helps Tom escape from the legal payment for his crime. So much for his fundamental principle. Breaks down when it comes to your family.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,

Tristram wrote: "Dear Pickwickians,I am posting the new chapter recaps today because tomorrow I will probably not have any time. I wish you all a Happy Easter!

This week saw our last round of chapters from Hard ..."

Happy Easter to you as well, Tristram, and to all Pickwickians. It looks like the Easter Bunny has brought us to the close of HT.

This chapter brings the novel's two angelic characters together as they search for Stephen and discover that he has fallen down an abandoned mine shaft called Old Hell Shaft. I continue to get echoes of Pilgrim's Progress in HT. Old Hell Shaft, where Stephen finds himself trapped, serves as both a physical constraint to Stephen and a representation of the multiple ways Stephen has been either abandoned or trapped in HT. Consider the list Tristram provides: drunken wife; unattainable love; shunned by fellow workers; sacked by Bounderby; entrapped by the whelp; slandered by Slackbridge.

Saint Stephen was stoned to death by others; here, in HT, Stephen Blackpool is subjected to painful punishment as well. While he articulates his position as "a muddle" Dickens also has Stephen reflecting Christain values. We are told that Stephen believed that a star " shined into his mind" and that his "dyin prayer [was] that aw th' world may on'y coom toogether more, an get a better unnerstan'in o'one another." It could be argued that Dickens is somewhat heavy-handed in this chapter, but I feel it is logical and effective.

I have to admit that I was disappointed with much of the resolution of the book.

I have to admit that I was disappointed with much of the resolution of the book. We never do learn why Bounderby concocted all that taradiddle about his youth. There seems to be some mental illness in that, but it doesn't show in his adult life that I saw.

Mrs. Pegler, as Tristram notes, falls out of the book. I guess she only shows up to humiliate Bounderby at the end, but why doesn't she resume her role of mother, since Bounderby is not effectively a widow and he had kicked Mrs Sparsit out.

Stephen falling into the pit is an unbelievable plot twist -- there were plenty of roads, lanes, and footpaths to get where he was going. It wouldn't happen. And then finding him just in time for him to make those dying remarks and then exit right, nope. Doesn't work for me.

Sleary joins Sissy in compounding a felony. So much for respect for the law. Bitzer may not be acting from the best motives, but he's right in bringing a fugitive to justice to pay for his crime. Dickens sets a very bad example of encouraging defiance of the law and support for criminals.

Since Bounderby will die in a few years, leaving Louisa still quite a young widow (and a wealthy one presumably), why doesn't she remarry and have a nice family? Despite her upbringing she's turned into a sensible and caring young woman. In today's world she could contribute to society even though unmarried, but in Coketown (or even Victorian England) much less so. What a waste of a good character. And what did she do wrong to not deserve a happy ending? (Ditto Mrs. Pegler?) Spark Notes claims that "everyone gets their just desserts...the characters who are clearly good are rewarded with happy endings, while those who are clearly bad end up miserable." Bounderby dies, but is he miserable in the meantime? Louisa isn't clearly good? Stephen wasn't clearly good, but deserved to die as a direct consequence of Tom's evil? And Tom gets to avoid jail and start a fresh life abroad? Not what I consider rewarding the good and punishing the bad.

Tristram wrote: "The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been speaking with th..."

Tristram wrote: "The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been speaking with th...""Amazing creatures they were in Louisa's eyes." Louisa once again enters the world of Sleary's Circus, but this time not to peek with Tom at a world apart from them as earlier in the novel, but to find Tom who is now part of the Circus.

There are three incidents of looking into a world not you own in this novel. The first is Tom and Louisa's peek under the tent and into the world of Sleary's Circus. The second in Mrs. Sparsit's peek into the emotional, sexually charged meeting of Harthouse with Louisa and the third is here, where we find Tom in disguise. This chapter offers great visuals. Mr. Gradgrind sitting " on the Clown's performing chair in the middle of the ring," the whelp " in his comic livery" and " black face," and Bitzer saying he "can't allow [him]self to be done by horse-riders." Unlike Dickens longer novels where the ending occurs over several chapters, HT is compressed and many our principle characters are gathered in a circus tent. There is irony here as the novel began in a schoolroom with the phrase "Now, what I want is, Facts." The novel is fast coming to its conclusion and is set here in a circus tent, with Tom in blackface, Louisa's eyes opened to a new world and Mr Gradgrind sitting on a clown's chair. The facts seem to have vanished into the world of the imagination.

H.T.'s end does give the reader the typical Victorian ending to a novel, but in a very confined manner. We still have the bad/evil characters punished. Tom, repentant, does not make it back to his home and family. Mr. Gradgrind is redeemed to a degree, and Bounderby dies. To me the most tragic figure is Louisa. She will never see her brother again. She will never be a wife again and have children, but she will painfully be witness to Rachael's slow aging and perennial caring for Stephen's wife. Hers, I think, is the bleakest of futures, and seemily unfair given her actual transgressions.

H.T.'s end does give the reader the typical Victorian ending to a novel, but in a very confined manner. We still have the bad/evil characters punished. Tom, repentant, does not make it back to his home and family. Mr. Gradgrind is redeemed to a degree, and Bounderby dies. To me the most tragic figure is Louisa. She will never see her brother again. She will never be a wife again and have children, but she will painfully be witness to Rachael's slow aging and perennial caring for Stephen's wife. Hers, I think, is the bleakest of futures, and seemily unfair given her actual transgressions.Sissy will marry, have children, and continue to be a person of imagination, and this too will Louisa witness. Does anyone else think that with the character of Louisa, Dickens has moved towards another level of realism and away from his former bland portrayal of the dutiful portrayal of a female?

I too feel it's a tragic end for Louisa but isn't it Dickens' statement that the damage is already done in childhood? No matter what the future could hold, it won't get through the exterior wall of 'facts' that have been built around her to allow any normal existence. That's what I perceive anyway.

I too feel it's a tragic end for Louisa but isn't it Dickens' statement that the damage is already done in childhood? No matter what the future could hold, it won't get through the exterior wall of 'facts' that have been built around her to allow any normal existence. That's what I perceive anyway.

I was disappointed that Harthouse and Tom both seemed to get away with their transgressions, and would have like to see some comeuppance, even - or maybe especially - Louisa shunning Tom for being such a selfish jerk.

I was disappointed that Harthouse and Tom both seemed to get away with their transgressions, and would have like to see some comeuppance, even - or maybe especially - Louisa shunning Tom for being such a selfish jerk. Everyman is right -- our morals and ethics sometimes fall by the wayside when our families are directly impacted. But what motivation did Sissy and Sleary have to abet Tom's escape? Sissy's love of the Gradgrinds and Sleary's fondness for the Jupes? I don't buy it. It may have been enough for them to keep their mouths shut, but not to actively assist in Tom's getaway. Particularly since Sissy was well aware that Tom's actions resulted in Stephen's death.

And speaking of Stephen... Oh my. If he'd just stopped talking, he may well have had to energy to survive. I kind of wanted to roll him right back into the abyss after awhile! Yes -- Stephen was a messiah figure, crucified for the sins of others, but even Jesus lost his temper from time to time, and was much pithier when speaking from the cross! Despite all that, I liked him. Always cheering for the underdog. :-)

By the way, Tristram -- I believe the ladies went for their walk in the country with the specific intent of looking for Stephen. I don't have the book with me, but I seem to remember that they were concerned that he hadn't shown up and, rather than sit around fretting, decided to be proactive and hope to meet him on the road or learn some news of his whereabouts. How fortuitous.

Despite my niggling complaints, I still liked Hard Times. As is often the case with Dickens, I enjoyed the peripheral characters more than the main characters. Mrs. Sparsit was a hoot, and I loved the staircase metaphor. I felt for Stephen and Rachael. Sure, they were unbelievably good, which could be frustrating, but I'm always a sucker for kind, moral characters, as long as they aren't too perfect. I also quite liked Mrs. Pegler. I would love for Dickens to have written a story (or a side story - HT was short enough that it could have been included) with some background info on her and how she and Bounderby grew into such an odd relationship. I don't imagine it ended well for her -- Bounderby's cover being blown, he probably took it out on her, and now she's probably banished for good. But I prefer to think that Louisa reached out to her mother-in-law and that they developed a warm, loving relationship.

As far as social commentary, I'm not sure what to think. It seems as if Dickens was in the corner of the working man, but had no use for unions. He obviously didn't like management, though. And it would seem he was also not a fan of the education system (though I'm not sure what that actually looked like in 19th century England). Marriage didn't come off too well in HT, either. The happiest couple was the Gradgrinds, and we didn't really witness any connubial bliss there.

And I'll end where we began, with sweet Merrylegs. Loyal and devoted to the end. The moral of the story for me is that getting involved with humans can cause heartache, but that dogs are the best friends you can have. Now, if you'll excuse me, I need to go hug Lily and Lucy. :-)

Happy Easter, everyone!

Kate wrote: "I too feel it's a tragic end for Louisa but isn't it Dickens' statement that the damage is already done in childhood? No matter what the future could hold, it won't get through the exterior wall of..."

Kate wrote: "I too feel it's a tragic end for Louisa but isn't it Dickens' statement that the damage is already done in childhood? No matter what the future could hold, it won't get through the exterior wall of..."Yes. A good point. By extension, a child like Sissy who is raised surrounded by wonder and encouraged to have and foster a healthy imagination will be a healthy and successful adult. How we would judge Bitzer is another matter.

Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative.

Peter wrote: "Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative. "

Peter wrote: "Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative. "Maybe the ending and tone of the story has a lot to do with the fact that his marriage was coming to an end by this time. Gloom, gloom and more gloom. Perhaps it reflects his notion of his own future - one with little hope or sunshine.

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been..."

Peter wrote: "Tristram wrote: "The next chapter with the very promising title „Whelp-hunting“ takes up the action exactly where the last chapter left it. The narrator informs us that while Mr. Gradgrind had been..."Thanks for your comments, Peter. You brought out a number of valuable points which I had overlooked in my haste to get to the end of the book. Very valuable.

Peter wrote: Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative."

Peter wrote: Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative."Well, yes, but what would D have done with him? Would need a whole nother Stephen type chapter for him to explain what he had been going through and why it took him so long to get back to Sissy. And that would have been a significant distraction, I think, from wrapping up the story. So maybe better that he died offstage.

Kate wrote: "Peter wrote: "Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative. "

Kate wrote: "Peter wrote: "Interesting that Dickens would not find some way to bring Sissy's long lost father back into the narrative. "Maybe the ending and tone of the story has a lot to do with the fact tha..."

Dickens's personal problems casting a shadow over his fiction is an interesting angle of looking at the novel, Kate! Maybe that explains why he denies Louisa a second and happier marriage - because the assumption that she has been emotionally blighted by her education could surely work as an explanation of why she allows everyone else around her to manoeuvre her into a marriage with Bounderby - her major reason paradoxically being Love, love for her brother, that is - but it surely does not explain why she should not learn to cope with her emotional problems and start a new life after all the misfortune she went through. Even Gradgrind was able to mend his ways, and Louisa is not as one-dimensional a character as her father (of whom, by the way, we might also assume that he was brought up in this heart-crippling way). So maybe Dickens wrote some of his personal bitterness into the story of Louisa.

Mary Lou wrote: "By the way, Tristram -- I believe the ladies went for their walk in the country with the specific intent of looking for Stephen."

Mary Lou wrote: "By the way, Tristram -- I believe the ladies went for their walk in the country with the specific intent of looking for Stephen."You are right there, Mary Lou. My memory tells me that Rachael was worried about Stephen taking so long to show up, and so it absolutely makes sense to believe that she and Sissy set out that morning with a view of running into him. Still, as Everyman points out, it is very strange that Stephen did not stick to the roads. Travelling would have been easier and quicker and less dangerous for somebody who would not just hike across-country.

Mary Lou wrote: "And speaking of Stephen... Oh my. If he'd just stopped talking, he may well have had to energy to survive. I kind of wanted to roll him right back into the abyss after awhile! Yes -- Stephen was a messiah figure, crucified for the sins of others, but even Jesus lost his temper from time to time, and was much pithier when speaking from the cross! Despite all that, I liked him. Always cheering for the underdog. :-)"

Mary Lou wrote: "And speaking of Stephen... Oh my. If he'd just stopped talking, he may well have had to energy to survive. I kind of wanted to roll him right back into the abyss after awhile! Yes -- Stephen was a messiah figure, crucified for the sins of others, but even Jesus lost his temper from time to time, and was much pithier when speaking from the cross! Despite all that, I liked him. Always cheering for the underdog. :-)"I really share your view of Stephen, Mary Lou! Except for that bit of cheering for the underdog. I normally do that, too, but not if the underdog is such a lapdog and seems to wallow in his sorrows to such an extent as Stephen does it. Dickens's prose here is very heavy-handed and an obvious instance of pandering to the sentimental tastes of Victorian readers: Stephen feels that he and his fellow-workers are in a muddle but he leaves it to others, those in authority, to remedy this situation. I am not in favour of social or political revolutions because revolutions only replace traditional ills with new ills, which are often more deadly and unjust still, but I would think that within the political system of the times, it would have been justified for the workers to pursue their own interests by forming unions and maybe establishing a political party. Political reforms in the 19th century would have favoured this course, so why is Dickens so sceptical about it?

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."

Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."Except that he helps Tom escape from the legal payment for his crime. So much for ..."

I fully agree with you here, Everyman: Tom has violated the law and ought to be punished according to the law. Sissy, however aids and abets in his escape, her motive probably being her attachment to the Gradgrind family and her fear that Mr. Gradgrind would not bear the public shame attached to Tom's being convicted as a criminal. So while I can understand why Sissy runs the risk of putting herself outside the law, I cannot believe that Mr. Sleary would have shielded a bank robber and accept the potential consequences - all the less so as Bitzer could easily have reported him and Sissy for helping Tom escape.

Tristram wrote: "I fully agree with you here, Everyman"

Tristram wrote: "I fully agree with you here, Everyman"Oh, isn't that wonderful? In that case, I don't. Even though you are right I don't agree.

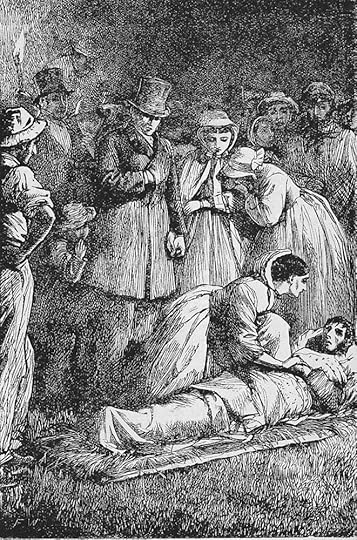

Finally we get to Fred Walker's fourth illustration for the novel. I say finally because knowing that he was the only artist to illustrate the novel while Dickens was alive I was always curious to see his illustrations and since he only made four illustrations it seemed to take a long time to get to them.

Finally we get to Fred Walker's fourth illustration for the novel. I say finally because knowing that he was the only artist to illustrate the novel while Dickens was alive I was always curious to see his illustrations and since he only made four illustrations it seemed to take a long time to get to them.

"Stephen Blackpool recovered from the Old Hell Shaft"

Fred Walker

1868 Library Edition of Dickens's works

Commentary:

"Walker's fourth plate is the most dramatic. The artist has chosen to show neither the mouth of the shaft nor the windlass used moments before in the rescue, but focuses on the moment when Rachel bends down to hold Stephen' s broken right hand: "She stooped down on the grass at his side, and bent over him until her eyes were between his and the sky, for he could not so much as turn them to look at her" (Book Three, Ch. 6). However, in the interests of staging Walker has her use her right hand to gently clasp Stephen's left as he lies, like Christ in the manger, on a bed of straw. Sissy Jupe must be the crying woman turned away from us since the other, centre, resembles Louisa in the first plate; the clean-shaven gentleman whose hand she holds cannot be the bearded Bounderby of the first plate, and so must be her father: "Standing hand-in-hand, they both looked down upon the solemn countenance." Apparently in the text Rachel is one one side of Stephen, Louisa on the other, but Walker has disposed the figures so that all facing forward, placing Gradgrind at the centre even though the letter-press indicates he is not present at the moment bends down to touch Stephen. Despite the sobbing of the women, the scene is imbued with the sacred stillness of a Renaissance Lamentation scene such as Giotto's in the Arena Chapel, Padua, the torch to the left of the plate pointing upward much as the rock does in the Giotto fresco, while Rachel, like Mary in the biblical scene, bends her face towards the victim's.

Curiously, aside from the angels hovering above Giotto's scene, "The Lamentation" contains nineteen figures--precisely the number in Walker' s plate, but whereas Giotto's Christ is parallel with the baseline, Walker has shown Stephen on an angle, so that his feet are closer to us than the rest of his body. Dickens mentions in specific terms only a few members of the crowd: Sissy, Rachael, Mr. Gradgrind, Louisa, Mr. Bounderby, and "the whelp," a surgeon, the crew of the windlass, the pitman, and (as in Giotto) "the women who wept aloud." Why Walker has chosen to include a child beside the figure of Gradgrind is unclear. Like young Tom, Bounderby is not evident; the gentleman beside the torch is probably the surgeon.

That the sun has already set is implied by the torch, not mentioned in the letter-press, which focuses upon the star rising in the "night sky." The torchlight plays in chiaroscuro upon the faces of those in front while those behind are obscured by the growing gloom. Thus, from the middle of the preceding page to the bottom of the facing page, the reader-viewer can alternate between verbal and visual texts, comparing and contrasting the competing narratives of Stephen' s final moments.

Since the plates reflect a careful reading of the letter-press, the obvious errors in captioning are somewhat disconcerting in that "Rachel" and "Tom Bounderby" undermine the authority of Walker's realisations. How these errors crept into the work is a matter of conjecture that the final volume of the Pilgrim Edition of Dickens' s correspondence may elucidate."

Just out of curiosity after reading the commentary I looked up the painting by Giotto. Here it is.

Commentary on all four illustrations:

"Although they lack the emblematic details and pictorial humor of Phiz' s best work for Dickens, these four plates reveal a careful reading of Dickens' s text and provide an accompaniment that heightens rather than detracts from the characterizations inherent in the letter-press. Although Walker in his programme of illustration emphasizes no one of the novel' s principals since Louisa, Tom, Rachel (spelled more biblically "Rachael" in the letter-press), and Stephen Blackpool each appear twice, he significantly undervalues the importance of Thomas Gradgrind, Sr., and Sissy Jupe, each of whom appears just once, lost in the crowd of twenty in the last plate, "Stephen Blackpool Recovered from the Old Hell Shaft." No character appears more than twice, reflecting the novel' s failure to provide a single informing consciousness. The series of four pictures is balanced in terms of exterior and interior scenes, and in terms of moments from the Rachel/Stephen and Louisa/Harthouse plots. The Blackpool sick-room counterpoints the Bounderby dining-room, and the banker's garden the mouth of the mineshaft, both representing Nature modified by Man for profit and for recreation.

An illustration by Harry French:

An illustration by Harry French:

"She Stooped Down On The Grass At His Side, And Bent Over Him."

Harry French

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

Commentary:

"In Cassell's Magazine of Art (1890), well-known artist George Du Maurier likened the process of book-illustration to staging a dramatic adaptation:

"To have the author's conceptions adequately embodied for [readers] in a concrete form is a boon, an enhancement of their pleasure. Their greatest pleasure of all, of course, is to see it all acted on the stage. . . . . But the stage is not always at one's command, and failing this, the little figures in the picture are a mild substitute for the actors at the footlights. They are voiceless and cannot move, it is true. But the arrested gesture, the expression of face, the character and costume, may be as true to nature and life as the best actor can make them. Within the limits assigned, these little dumb motionless puppets . . . may continue to haunt the memory when the letter-press they illustrate is forgotten."

This is precisely the effect that Harry French has created in the seventeenth plate for the Household Edition of Hard Times. With Stephen's last words amounting almost to a peroration on the ills of industrial society, one might describe the scene as "operatic." As with the death of any significant figure in grand opera, there must be a large accompanying chorus to echo the lamentations of the principal grievers. Indeed, Dickens describes the bystanders as a "throng" (III: 6), among whom a number of women form a chorus of anguish which antiphonally plays behind the parting words of Rachael and Stephen. Not so in the onlookers depicted in French's plate, in which there are only two women (Louisa and Sissy) and a small number of men, some in workers' caps, others in middle-class top-hats. However, French effectively employs Stephen's "pale, worn, patient face" to evoke recollections of Renaissance paintings of the crucified Christ. Since Stephen has already called both Sissy and Rachael to his side, the caption "She Stooped Down On The Grass At His Side, And Bent Over Him" is not entirely accurate. Although Louisa and her father are present at that moment, we are not aware of Gradgrind's presence until later in the chapter. In the plate, however, French has accorded father and daughter a place of prominence, the light from the torches throwing a chiaroscuro across their pensive countenances. By placing their left hands at their chins French is suggesting that they are endeavoring to solve a riddle, perhaps how Stephen fell into the shaft, and even perhaps whether he was involved in the bank robbery at all. French may have conflated two narrative moments, Rachael's taking Stephen's hand (as the caption indicates) and Stephen's responding to Gradgrind's "troubled" countenance by suggesting the father consult Tom in order to clear Stephen of the robbery accusation."

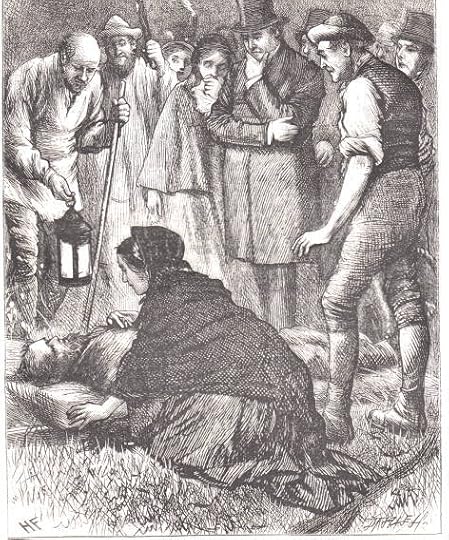

Another Harry French illustration, the 18th:

Another Harry French illustration, the 18th:

"'Now, Thethilia, I Don't Athk To Know Any Thecreth, But I Thuppothe I May Conthider Thith To Be Mith Thquire.'"

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

Commentary:

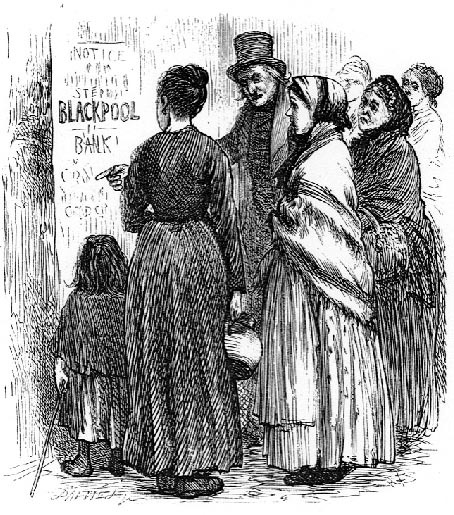

"Sleary, costumed as a ringmaster arranges for Tom's escape in disguise. With his son's safety apparently secure, Gradgrind broadcasts the truth about the bank robbery in the twentieth plate. The thematic connection is the revealing of guilt for a crime committed as a logical consequence of Gradgrind's inculcating his son with the Utilitarian doctrine of self-interest. The visual connection between these two plates is the figure of Sissy Jupe, whose altruism and moral integrity have saved both Tom and his sister. Curiously, as the grass flooring of Sleary's tent makes obvious, the illusory world of the circus combines nature and civilization; it offers a synthetic family more supportive emotionally than the book's real families, and so improves upon nature. Tom's admission of guilt shortly after the moment realised in Plate 18 leads directly to the posted broadsheet of Plate 20."

The illustrations and their accompanying commentaries were fascinating. I have read the comments closely and am increasingly becoming much more impressed with the attention to the text, to detail and, ultimately, to the wider world of art. I think to call Browne, Cruikshank and the various people who illustrate these novels as merely illustrators does not do justice to their work. They are artists.

The illustrations and their accompanying commentaries were fascinating. I have read the comments closely and am increasingly becoming much more impressed with the attention to the text, to detail and, ultimately, to the wider world of art. I think to call Browne, Cruikshank and the various people who illustrate these novels as merely illustrators does not do justice to their work. They are artists.Thanks, as always, Kim for giving us another dimension to Dickens's novels.

Another Harry French illustration:

Another Harry French illustration:

"Here Was Louisa, On The Night Of The Same Day, Watching The Fire As In Days Of Yore."

Harry French

Part III Chapter 9

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

Commentary:

"After Tom's escape from Bitzer, the most developed scene in the last chapter of the letterpress and the comedic climax is the quarrel between Mr. Bounderby and Mrs. Sparsit. French, however, passes over this uproarious scene to dwell upon a small but significant sentimental moment. In contrast to Dickens's reward for Sissy's virtue, "happy children loving her" (III: 9), Louisa is and will be alone, although like the reformed Scrooge in A Christmas Carol (1843), she will derive consolation from others' children.

Louisa's image recalls that of many a nineteenth-century heroine; the pensive, alienated young woman, recalling "Patient Griselda," is almost a Victorian commonplace--compare Louisa here to Bathsheba Everdene in Helen Paterson's initial-letter vignette "B" of her in November 1874 issue of The Cornhill Magazine's serialization of Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd, lost in thought at the window of the Three Choughs Inn after learning of the (supposed) drowning of her husband, Frank Troy. It is an image of loss and resignation. Like Bathsheba, Louisa has health, affluence, and youth, but contemplates a future without her beloved brother or a husband and children of her own. Books, lining the shelves of her room, are henceforth to be her intimate companions and the basis of her inner life. Despite the wistful smile on her countenance, French depicts her as unfilled, but, as the vases on her mantle suggest, her life will have greater balance than when she was Bounderby's ornament and trophy."

Here is the 20th and the last Harry French illustration. It is untitled but has this one sentence with it:

Here is the 20th and the last Harry French illustration. It is untitled but has this one sentence with it:"A crowd has gathered in the street to read one of the posted broadsides exonerating Stephen Blackpool of charges associated with the bank robbery"

Harry French

Illustration for Dickens's Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:

An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:

"Rachael Caught Her in Both Arms, with a Scream That Resounded Over the Wide Landscape"

Part III Chapter 6

Charles S. Reinhart

Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870

Commentary:

"Sissy in fashionable, middle-class dress and Rachael (identifiable by her large plaid shawl) recoil from the mouth of the Old Hell Pit, near whose margin they have just discovered Stephen Blackpool's hat. Just after the moment realized, the pair spring back from the edge and fall on their knees, holding each other in fright as Stephen's fate becomes suddenly apparent. The time is noon on a fine fall Sunday.

Suspecting that Stephen may have fallen ill upon the road four days earlier, Sissy and Rachael agreed on the Friday to walk into the country on the following Sunday in hopes of learning of his whereabouts. As is consistent with Dickens's letterpress, the plate depicts an autumnal landscape in the background -- the novel indicates the setting is "about midway between the town and Mr. Bounderby's retreat" -- certainly, Sissy and Rachael are far enough from Coketown that they have escaped its smoke-serpents. Beneath a clear sky leafless trees proclaim the season. In the left rear is a fragment of rotten fence but recently broken. Although Reinhart does not show Stephen's footprints, at Rachael's feet on the grass lies Stephen's hat, which in the text Sissy has just taken up to read Stephen's name written on the inside band. Presumably she is still holding the hat as she catches her companion on " the brink of a black ragged chasm hidden by thick grass" in the foreground. Reinhart has captured well the look of horror on their faces as they realize the fate they have narrowly avoided but which, in all likelihood, has overtaken the honest factory-hand."

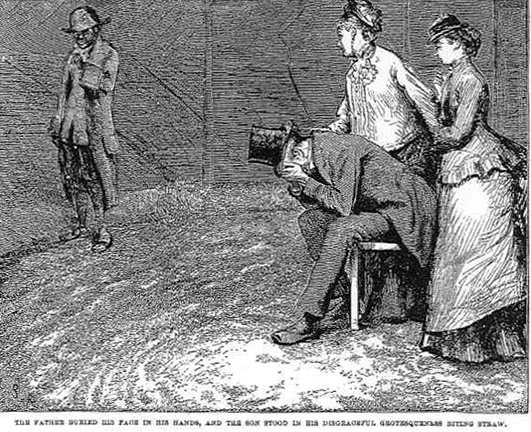

"The Father Buried His Face in His Hands, And the Son Stood in His Disgraceful Grotesqueness Biting Straw."

Part III Chapter 7

Charles S. Reinhart

Commentary:

"Throughout Reinhart's pictorial programme, Thomas Gradgrind (depicted in detail five times) is something of a "joke" figure until almost the end. In Plate 2, he is a wooden, black column (shades of Charlotte Brontë's description of the Reverend Mr. Brocklehurst in Jane Eyre, perhaps) who cannot see what is immediately before him (his children peeping through a hole in the circus tent) without the aid of his monocle. Complementing this depiction of monocular vision, Reinhart implies that Gradgrind's physical stiffness is a metaphor for his Utilitarian dogmatism and mental inflexibility. Gradgrind's misshapen, bald skull (reminiscent of the skulls of the precursors of homo erectus), bristling eyebrows, and hooked nose impart a bird-like quality in plate 3. In the sixth plate, illustrating his marriage proposal to Louisa on Bounderby's behalf, Gradgrind's skull is noticeably indented on the top, as if he had an extra brain, as he discounts the importance of mutual affection in a marriage. In the thirteenth plate, however, Gradgrind is, as Dickens observes he should be, "much softened" by recent experiences and much more human in aspect, as he puts his hand to his brow to signify his despondency at the failure of rational knowledge (suggested by the map behind his head) to produce happy, well-adjusted children in his own house. This is the chastened figure of a father who candidly admits to his personal and political ally (and unnaturally old son-in-law whom Louisa has just left for good) that "we are all liable to mistakes" (Book III, Ch. 3).

We come, then, to a "forlorn" Gradgrind, bent over, humiliated but ultimately humanized by despair in the fifteenth and final plate, appalled by his failure to inculcate any sense of morality in his eldest son. The "whelp" himself is characteristically biting a straw as he stands apart from the concerned group of Louisa (right), Sissy (hand extended, comforting Gradgrind), and the grieving father. In the center of the sawdust ring, as in Dickens's text, Gradgrind sits in the performing clown's chair, for fortune has exposed the utter folly of his "system" of education and child-rearing, and he is Fortune's fool indeed. In contrast to his respectably dressed sister and father, Tom is still clad in his disguise, the "comic livery" (Book III, Ch. 7) of one of Jack's black-faced servants in "Jack the Giant Killer." While the figures of Sissy and Louisa are primarily white, Tom is thoroughly black. The ill-fitting, outlandish outfit specified by the text -- including exaggerated waistcoat, the mad cocked hat, and beadle's coat with immense cuffs and pock-flaps -- is not as repulsive in its total effect visually as Dickens insists it should be "grimly, detestably, ridiculously shameful." What Reinhart is successful in suggesting, through Tom's posture, is his lack of concern for those who care about him; he is withdrawn, and does not even glance in their direction. Already, however, he has in fact come down from the benches into the ring, and confessed to the robbery, so that Reinhart has conflated the moment of description (when Tom is still on the back benches) with the moment indicated by the caption, immediately after Tom, like a good (i. e., amoral, logical) Utilitarian, has archly pleaded statistical necessity for his violating the trust of his employer. To this shuffling off of personal responsibility for the crime (which, in implicating an innocent man, has caused that man's death), "Gradgrind buried his face in his hands," while, descending the Darwinian scale of evolution (Origin of Species having been published in 1859 but The Descent of Man in 1871, after the Household edition of Hard Times, one could make too much of the simian imagery in Dickens's text, but Reinhart's illustration at least post-dates the dawn of Darwinism), his monkey-pawed son bites his straw. But in Reinhart's characterization of Tom there is no redeeming white in either his hands or face; the artist's depicting Tom with utterly seamless, black pigmentation implies no likelihood of redemption for Gradgrind's prodigal son."

This plate illustrates Charles Dickens's Hard Times, which appeared in American Household Edition, 1870.

And that I believe wraps up the illustrations for this book, on to the next one.

Kim wrote: "Oh, isn't that wonderful? In that case, I don't. Even though you are right I don't agree. ."

Kim wrote: "Oh, isn't that wonderful? In that case, I don't. Even though you are right I don't agree. ."Whew. I live in terror of the day when you might ever actually agree with Tristram and me.

Thank heavens it hasn't come yet. Please keep sparing us.

Kim wrote: "An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:

Kim wrote: "An illustration by Charles S. Reinhart:"Rachael Caught Her in Both Arms, with a Scream That Resounded Over the Wide Landscape" "

Rachel doesn't look like she's screaming, she looks like she's an ugly hag with a warped character.

And at least in this plate, it's clear that Reinhart can't draw hands. Is this true throughout his illustrations? I know hands are hard (my wife is an artist, but she can draw them beautifully, which makes her a very skilled artist).

Kim, thanks for this richness of illustrations and comments. Like Peter, I think that most of the illustrators are true artists in their own right.

Kim, thanks for this richness of illustrations and comments. Like Peter, I think that most of the illustrators are true artists in their own right.What I find proves Harry French's artist's feeling for the text best is that he has decided to pass over the Sparsit-Bounderby confrontation and chose to draw a picture of Louisa sitting in front of the grate once again. I would not even say, like the comment, that this is a detail but I think that we were all asking ourselves what Louisa's future life might be like, and so it shows great judgment in Harry French to have picked this scene instead of the more sensational Sparsit-Bounderby-duel.

I am not so sure, however, if the comparison between Louisa and Bathsheba Everdene as is made in the comment holds water: After all, Bathsheba was very much in love with Sergeant Troy whereas this cannot be said with regard to Louisa and her husband. Her grief is even deeper than that of Bathsheba, who mourns for the dumb officer, and who is not far from being superficial and spoilt herself. Louisa does not mourn for the loss of another person but she has the feeling that there is something wrong with herself, that she cannot love like other people, and I think that is why she secludes herself in the library.

The final chapters left me with the impression that Dickens was constrained by length limits, and rushed the ending (with the exception, as others have noted, of Stephen's long-winded death speech!). It seemed strange that characters who he introduced at some length (eg. Mrs. Blackpool & Sissy's father) were finished off by a sentence or two.

The final chapters left me with the impression that Dickens was constrained by length limits, and rushed the ending (with the exception, as others have noted, of Stephen's long-winded death speech!). It seemed strange that characters who he introduced at some length (eg. Mrs. Blackpool & Sissy's father) were finished off by a sentence or two. I did not find Louisa's fate to be nearly as tragic as that of Stephen & Rachael. I had a similar thought as French's commentator (thank you, Kim) that his tragic death was of operatic proportions, and was increased by the irony of his wife surviving him. And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe, though I suppose not surprising considering her character.

I didn't think Louisa's future was necessarily unfulfilled. Don't all children love her? (Perhaps her younger siblings have children, as well as Sissy. She might have a large extended family.) We don't know that she wanted children of her own, or that she wanted to remarry, after her experience with Bounderby and Harthouse. It sounds like she becomes a fun aunt, a humanitarian, and a patron of the arts. We might also remember that widows had more freedom than wives or single women in this period.

Peter wrote: "This chapter offers great visuals. Mr. Gradgrind sitting " on the Clown's performing chair in the middle of the ring," the whelp " in his comic livery" and " black face," and Bitzer saying he "can't allow [him]self to be done by horse-riders."..."

Peter wrote: "This chapter offers great visuals. Mr. Gradgrind sitting " on the Clown's performing chair in the middle of the ring," the whelp " in his comic livery" and " black face," and Bitzer saying he "can't allow [him]self to be done by horse-riders."..."The images of this chapter struck me too, Peter. I enjoyed your comparison with the novel opening. This part gave me a strong sense of balance and symmetry to the novel. Gradgrind appears like a broken ringmaster of a failed circus (perhaps shadowing Mr. Jupe's failure as a clown.) Great contrast between the blackened Tom and nearly albino Bitzer -- maybe suggesting together the failure, too, of taking a black & white factual perspective?

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Tristram wrote: "It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for.."Except that he helps Tom escape from the legal payment for his crime..."

Interesting questions. I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. Considering Dickens' view of the law, it didn't seem surprising to me that he might excuse Gradgrind for avoiding it. I expect if Stephen had been convicted, he would have been given a much more severe punishment than a son of a MP. And I lost of track of how old Tom is by the end -- would he still be a minor? In the posters exonerating Stephen, Gradgrind gives his son's youth as an extenuating circumstance. But he does publish his guilt, so would still have to bear the shame.

Vanessa wrote: "Great contrast between the blackened Tom and nearly albino Bitzer -- maybe suggesting together the failure, too, of taking a black & white factual perspective? "

Vanessa wrote: "Great contrast between the blackened Tom and nearly albino Bitzer -- maybe suggesting together the failure, too, of taking a black & white factual perspective? "Ooh nice, Vanessa! I don't know if Dickens did this intentionally, but it fits beautifully. (You must be an English lit. teacher!)

Ironically, though, Dickens was not too alien to black-and-white-thinking, when you come to consider his idealized heroines which are much voider of life than his fiendish blackguards.

Ironically, though, Dickens was not too alien to black-and-white-thinking, when you come to consider his idealized heroines which are much voider of life than his fiendish blackguards.

Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe, though I suppose not surprising considering her character. "

Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe, though I suppose not surprising considering her character. "I fully agree, Vanessa. And I suspect that Dickens chose that ending for her, i.e. a life of toils but of contentment in order to forestall any suspicions of his encouraging unionism. Rachael's readiness to carry her cross in meekness is well in line with Stephen's promise not to enter any union.

Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"

Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"I'm in the first few chapters of a new non-fiction by David Brooks called "The Road to Character" which, so far, seems to delve into the evolution of personal happiness and the devolution of character, looking historically (through the 20th century) at the emphasis we place on our own comfort and joy v. our place in society and our communities. I think Rachael would be a perfect example of the types of things Brooks touches on, and I see Dickens' ending for her as much more realistic because of Brooks' observations than I might have otherwise. We do, here in the 21st century, have a much different perspective than our forebears did when it comes to duty, happiness, etc. (Ties in, too, with the "entitlement" thread on another forum.)

Vanessa wrote: "We might also remember that widows had more freedom than wives or single women in this period. ."

Vanessa wrote: "We might also remember that widows had more freedom than wives or single women in this period. ."In some ways, yes, if they had money. But in sexual or emotional freedom, I don't think so. She's still a young woman. She either has to live the rest of her life without sex, or she has to flout the mores of her society and be drummed out of decent society. Not that sex is the only reason to get married, but in her day, for decent women, it was the only way to reach any kind of sexual fulfillment and still be accepted in decent society.

Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."

Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."But isn't there a major difference between transportation as a criminal to a penal colony (probably Australia) and voluntary exile to a country where he can be accepted as a respectable, decent young man with the opportunities that provides?

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"I'm in the first few chapters of a new non-fiction by David Brooks called "The Road..."

I hope you don't misunderstand me, Mary Lou: I consider the ending Dickens wrote for Rachael quite realistic but still I think that his day and age would also have allowed for a different ending, which would have made her less content and therefore also less soothing to middle- and upper-class readers' notions of how to address social wrongs. After all, the 19th century saw the rise of individualism, which became more and more prevalent in our time - often to the detriment of values that I would consider important and that are at the root of real freedom and liberty. The book you refer to sounds quite interesting.

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."But isn't there a major difference between transportation as a criminal ..."

There was probably a big difference, but - as a later Dickens novel shows us - it was also possible for a transported criminal to become wealthy and successful through hard work in his new country once he had served his time.

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "Great contrast between the blackened Tom and nearly albino Bitzer -- maybe suggesting together the failure, too, of taking a black & white factual perspective? "

Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "Great contrast between the blackened Tom and nearly albino Bitzer -- maybe suggesting together the failure, too, of taking a black & white factual perspective? "Ooh nice, Vanessa!..."

Thanks, Mary Lou. (Maybe worse... I'm a writer :) I think symbols can be created at the subconscious level, so I'd be curious to know if Dickens intended this contrast!

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"

Tristram wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "And Rachael's cheerful contentment with her 'natural lot' was disappointing and hard to believe"I'm in the first few chapters of a new non-fiction by David Brooks..."

I haven't been able to forget the (edited out) gruesome details of Rachael's sister's death. I would have expected Rachael's maternal instinct to override her sense of duty to her 'natural lot' in society, and that she would have joined the fight for better working conditions -- a different kind of duty, I suppose.

I do agree our sense of duty vs. personal happiness has changed over the centuries. Perhaps we've begun to swing back as the global community confronts the environmental mess we've created for future generations. Yes, an interesting topic.

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "We might also remember that widows had more freedom than wives or single women in this period. ."

Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "We might also remember that widows had more freedom than wives or single women in this period. ."In some ways, yes, if they had money. But in sexual or emotional freedom, I don't ..."

I agree, there would be a price to pay, either way. But considering that some men in this era didn't believe women (at least, the respectable kind!) were capable of sexual pleasure, marriage wouldn't necessarily have provided Louisa fulfilment in that regard. She would also have faced the possibility of dying in childbirth, or worse, the high risk of infant mortality. Dickens avoids this subject with Louisa's marriage to Bounderby, but I'm still grimacing when I imagine it...!

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."

Tristram wrote: "Everyman wrote: "Vanessa wrote: "I felt Tom was punished, perhaps in a similar way to what the law could have demanded -- transportation. ."But isn't there a major difference between transportati..."

Dickens evidently thought Australia was a great place to send his sons :) Although I'm sure a penal colony was no picnic, I'm not convinced Tom would have received a harsh sentence, as the young son of a MP. (I also recall that Harthouse did not think the sum stolen was very high. I suspect this might have been judged as relative to the class of the accused.) Wherever he went, Tom would have some difficulty arriving without letters of reference, which were often the doorway to colonial opportunities.

Vanessa wrote: "Although I'm sure a penal colony was no picnic, I'm not convinced Tom would have received a harsh sentence, as the young son of a MP..."

Vanessa wrote: "Although I'm sure a penal colony was no picnic, I'm not convinced Tom would have received a harsh sentence, as the young son of a MP..."I had overlooked the possible effect of his father being an MP. Good point.

Though it might have been an added incentive for his father to get him out of the country; if it had come out that his son was a bank thief, would he have been likely to lose his seat?

Interesting question. I was impressed that Gradgrind continued as an MP under the circumstance, and endured the taunts of his former political associates. Dickens suggests this is because of his change of beliefs, but I also wonder if the news of his son's theft would have reached beyond Coketown? Either way, I felt really sorry for Gradgrind by the end of the novel.

Interesting question. I was impressed that Gradgrind continued as an MP under the circumstance, and endured the taunts of his former political associates. Dickens suggests this is because of his change of beliefs, but I also wonder if the news of his son's theft would have reached beyond Coketown? Either way, I felt really sorry for Gradgrind by the end of the novel.

I am posting the new chapter recaps today because tomorrow I will probably not have any time. I wish you all a Happy Easter!

This week saw our last round of chapters from Hard Times, and we once again witness how Dickens ties his loose ends together and sees – nearly – every character out of the story. Some have to leave earlier than others, though – and this is also the case in Chapter 6 of the Third Part, which bears the silvery title “The Starlight”. It begins on the Sunday after the revelation of Mr. Bounderby’s family affairs, and we accompany Rachael and Sissy, who met – whysoever – to walk in the country. As Coketown’s chimneys spoil the immediate countryside around it, they have to go by train for a few stations to find some unspoilt countryside to walk in, but even the place where they leave the train bears the marks of industrialization:

”They walked on across the fields and down the shady lanes, sometimes getting over a fragment of a fence so rotten that it dropped at a touch of the foot, sometimes passing near a wreck of bricks and beams overgrown with grass, marking the site of deserted works. They followed paths and tracks, however slight. Mounds where the grass was rank and high, and where brambles, dock-wee, and such-like vegetation, were confusedly heaped together, they always avoided; for dismal stories were told in that country of the old pits hidden beneath such indications.”

In one of these places, the two women find a hat which Rachael picks up and identifies as Stephen Blackpool’s hat, his name being written on the inside. At first they think that maybe he has fallen victim to some highwaymen, but then they see ”the brink of a black ragged chasm hidden by the thick grass”, and they immediately realize that Stephen must have fallen into one of those abandoned and badly-secured pits. Sissy begs Rachael to remain at the opening of the pit while she herself rushes off to get some help, which gives me time to ask myself – and you Pickwickians:

Is there any sort of pit, of misery, of humiliation, of dire strait that Stephen would not get himself into? A drunken wife, an unattainable love, being shunned by his fellow-workers and sacked by Bounderby, led down the garden path by the whelp and being suspected of a bank robbery, having to leave his hometown and to find a new job under a new name, slandered by Slackbridge and now old Stephen falls into an deserted pit … and he loses his hat. But mind you! He never gets angry and thirsts for some retribution, but bears it all in a meek good spirit. I cannot really say that … but wait, Sissy is back!

Sissy has mustered some people for help. They say that the Old Hell Shaft – of course, Stephen would fall into a shaft with a bad reputation – has already taken quite a toll of human lives, and eventually they start their rescue measures for the person they have ascertained to be still alive. In the course of events, nearly all the important characters of the book are assembled in the place, i.e. Mr. Gradgrind, Mr. Bounderby and the whelp. When they finally retrieve Stephen, it goes like this:

”A low murmur of pity went round the throng, and the women wept aloud, as this form, almost without form, was moved very slowly from its iron deliverance, and laid upon the bed of straw. At first, none but the surgeon went close to it. He did what he could in its adjustment on the couch, but the best that he could do was to cover it. That gently done, he called to him Rachael and Sissy. And at that time the pale, worn, patient face was seen looking up at the sky, with the broken right hand lying bare on the outside of the covering garments, as if waiting to be taken by another hand.”

The “bed of straw” detail rang a bell in my mind, and my impression would become stronger when Stephen kept making references to a certain star – and then there is the title of the chapter, too. Now, Stephen asks Rachael to come near him and she does, and then Stephen gives quite a little monologue, and it stands to reason that he might have survived after all, had he not spent so much of his little strength on sermonizing and wasted so much time in doing so. But what he says, is probably essential to the message of the novel. Here are some bits:

”’ […] See how we die an’ no need, one way an’ another—in a muddle—every day! […]Thy little sister, Rachael, thou hast not forgot her. Thou’rt not like to forget her now, and me so nigh her. Thou know’st—poor, patient, suff’rin, dear—how thou didst work for her, seet’n all day long in her little chair at thy winder, and how she died, young and misshapen, awlung o’ sickly air as had’n no need to be, an’ awlung o’ working people’s miserable homes. A muddle! Aw a muddle! […]I ha’ seen more clear, and ha’ made it my dyin prayer that aw th’ world may on’y coom toogether more, an’ get a better unnerstan’in o’ one another, than when I were in ’t my own weak seln.’”

This is the gist of it all, but Stephen says a lot more, but – as the narrator points out –

”He faintly said it, without any anger against any one. Merely as the truth.“

Had he said it with a little more anger, he might have seemed more like a real person and less like a cardboard character – but then this would have played into the hands of trade unionism and turned the whole problem from a merely moral question into a social one.

Before Stephen dies, he also asks Mr. Gradgrind to clear his name of all vile suspicion connected with the bank robbery, and he tells the old man that his son will be able to tell him how to do this.