The History Book Club discussion

CIVIL RIGHTS

>

IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT OF 1965

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Books on immigration law itself are mostly law school textbooks - no wonder no one reads them! Immigration IS a complex topic, to be sure. Here is something that offers a look at various immigration issues:

Books on immigration law itself are mostly law school textbooks - no wonder no one reads them! Immigration IS a complex topic, to be sure. Here is something that offers a look at various immigration issues: by Rachel Buff

by Rachel BuffPunctuated by marches across the United States in the spring of 2006, immigrant rights has reemerged as a significant and highly visible political issue. Immigrant Rights in the Shadows of U.S. Citizenship brings prominent activists and scholars together to examine the emergence and significance of the contemporary immigrant rights movement. Contributors place the contemporary immigrant rights movement in historical and comparative contexts by looking at the ways immigrants and their allies have staked claims to rights in the past, and by examining movements based in different communities around the United States. Scholars explain the evolution of immigration policy, and analyze current conflicts around issues of immigrant rights; activists engaged in the current movement document the ways in which coalitions have been built among immigrants from different nations, and between immigrant and native born peoples. The essays examine the ways in which questions of immigrant rights engage broader issues of identity, including gender, race, and sexuality.

A book on immigration in America:

A book on immigration in America:Three Worlds of Relief: Race, Immigration, and the American Welfare State from the Progressive Era to the New Deal

by Cybelle Fox

by Cybelle FoxSynopsis

Three Worlds of Relief examines the role of race and immigration in the development of the American social welfare system by comparing how blacks, Mexicans, and European immigrants were treated by welfare policies during the Progressive Era and the New Deal. Taking readers from the turn of the twentieth century to the dark days of the Depression, Cybelle Fox finds that, despite rampant nativism, European immigrants received generous access to social welfare programs. The communities in which they lived invested heavily in relief. Social workers protected them from snooping immigration agents, and ensured that noncitizenship and illegal status did not prevent them from receiving the assistance they needed. But that same helping hand was not extended to Mexicans and blacks. Fox reveals, for example, how blacks were relegated to racist and degrading public assistance programs, while Mexicans who asked for assistance were deported with the help of the very social workers they turned to for aid.

Drawing on a wealth of archival evidence, Fox paints a riveting portrait of how race, labor, and politics combined to create three starkly different worlds of relief. She debunks the myth that white America's immigrant ancestors pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, unlike immigrants and minorities today. Three Worlds of Relief challenges us to reconsider not only the historical record but also the implications of our past on contemporary debates about race, immigration, and the American welfare state.

Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity

Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity by David G. Gutiérrez

by David G. GutiérrezSynopsis

Covering more than one hundred years of American history, Walls and Mirrors examines the ways that continuous immigration from Mexico transformed--and continues to shape--the political, social, and cultural life of the American Southwest. Taking a fresh approach to one of the most divisive political issues of our time, David Gutiérrez explores the ways that nearly a century of steady immigration from Mexico has shaped ethnic politics in California and Texas, the two largest U.S. border states.

Drawing on an extensive body of primary and secondary sources, Gutiérrez focuses on the complex ways that their pattern of immigration influenced Mexican Americans' sense of social and cultural identity--and, as a consequence, their politics. He challenges the most cherished American myths about U.S. immigration policy, pointing out that, contrary to rhetoric about "alien invasions," U.S. government and regional business interests have actively recruited Mexican and other foreign workers for over a century, thus helping to establish and perpetuate the flow of immigrants into the United States. In addition, Gutiérrez offers a new interpretation of the debate over assimilation and multiculturalism in American society. Rejecting the notion of the melting pot, he explores the ways that ethnic Mexicans have resisted assimilation and fought to create a cultural space for themselves in distinctive ethnic communities throughout the southwestern United States.

Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America

Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America by Mae M. Ngai

by Mae M. NgaiSynopsis

This book traces the origins of the "illegal alien" in American law and society, explaining why and how illegal migration became the central problem in U.S. immigration policy--a process that profoundly shaped ideas and practices about citizenship, race, and state authority in the twentieth century.

Mae Ngai offers a close reading of the legal regime of restriction that commenced in the 1920s--its statutory architecture, judicial genealogies, administrative enforcement, differential treatment of European and non-European migrants, and long-term effects. In well-drawn historical portraits, Ngai peoples her study with the Filipinos, Mexicans, Japanese, and Chinese who comprised, variously, illegal aliens, alien citizens, colonial subjects, and imported contract workers. She shows that immigration restriction, particularly national-origin and numerical quotas, re-mapped the nation both by creating new categories of racial difference and by emphasizing as never before the nation's contiguous land borders and their patrol. This yielded the "illegal alien," a new legal and political subject whose inclusion in the nation was a social reality but a legal impossibility--a subject without rights and excluded from citizenship. Questions of fundamental legal status created new challenges for liberal democratic society and have directly informed the politics of multiculturalism and national belonging in our time.

Ngai's analysis is based on extensive archival research, including previously unstudied records of the U.S. Border Patrol and Immigration and Naturalization Service. Contributing to American history, legal history, and ethnic studies, Impossible Subjects is a major reconsideration of U.S. immigration in the twentieth century.

At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration During The Exclusion Era, 1882 1943|

At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration During The Exclusion Era, 1882 1943| by Erika Lee

by Erika LeeSynopsis

With the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Chinese laborers became the first group in American history to be excluded from the United States on the basis of their race and class. This landmark law changed the course of U.S. immigration history, but we know little about its consequences for the Chinese in America or for the United States as a nation of immigrants.

At America's Gates is the first book devoted entirely to both Chinese immigrants and the American immigration officials who sought to keep them out. Erika Lee explores how Chinese exclusion laws not only transformed Chinese American lives, immigration patterns, identities, and families but also recast the United States into a "gatekeeping nation." Immigrant identification, border enforcement, surveillance, and deportation policies were extended far beyond any controls that had existed in the United States before.

Drawing on a rich trove of historical sources--including recently released immigration records, oral histories, interviews, and letters--Lee brings alive the forgotten journeys, secrets, hardships, and triumphs of Chinese immigrants. Her timely book exposes the legacy of Chinese exclusion in current American immigration control and race relations.

And Still They Come: Immigrants and American Society 1920 to the 1990s

And Still They Come: Immigrants and American Society 1920 to the 1990s by Elliott Robert Barkan (no photo)

by Elliott Robert Barkan (no photo)Synopsis

In this distinctive study of the impact of immigration and ethnicity on twentieth-century America, Barkan thoughtfully examines the changing composition of our immigrant populations, highlighting the ways in which certain facets of the struggle to adapt to American society have persisted from the 1920s until the 1990s. Going beyond the immigrant experience, Barkan considers the ways in which second- and third-generation Americans stress integration, even as they cling to important components of their ethnicity, not only adapting to American culture but shaping it. Featuring a moving photographic essay and coming alive with first-person accounts, And Still They Come is certain to provide important food for thought as Americans once more consider the narrowing gateways to the nation.

The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 - 1921

The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 - 1921 by Alan M. Kraut (no photo)

by Alan M. Kraut (no photo)Synopsis

In the two decades since the first edition of this tremendously successful book appeared, a vast scholarship undertaken by historians, sociologists, economists, and cultural anthropologists has altered the contours of American immigration history, challenging scholars to rethink long-held perspectives.

Insights derived from these diverse sources enrich the second edition of this popular text and have prompted important changes in emphasis and interpretation. Thoughtfully written to help student readers appreciate the varied pre- and post-migration experiences of the many groups and individuals who came to, and came to shape, the United States during this busy period, The Huddled Masses is essential reading for all enrolled in the United States history survey as well as specialized courses in Immigration and Ethnic Studies.

The Huddled Masses Myth: Immigration And Civil Rights

The Huddled Masses Myth: Immigration And Civil Rights by

by

Kevin R. Johnson

Kevin R. JohnsonSynopsis

Despite rhetoric that suggests that the United States opens its doors to virtually anyone who wants to come here, immigration has been restricted since the nation began. In this book, Kevin R. Johnson argues that immigration policy reflects the social hierarchy that prevails in American society as a whole and that immigration reform is intertwined with the struggle for civil rights.

The "Huddled Masses" Myth focuses on the exclusion of people of color, gays and lesbians, people with disabilities, the poor, political dissidents, and other disfavored groups, showing how bias shapes the law. In the nineteenth century, for example, virulent anti-Asian bias excluded would-be immigrants from China and severely restricted those from Japan. In our own time, people fleeing persecution and poverty in Haiti generally have been treated much differently from those fleeing Cuba. Johnson further argues that although domestic minorities (whether citizens or lawful immigrants) enjoy legal protections and might even be courted by politicians, they are regarded as subordinate groups and suffer discrimination. This book has particular resonance today as the public debates the uncertain status of immigrants from Arab countries and of the Muslim faith.

A Companion to American Immigration

A Companion to American Immigration by Reed Ueda (no photo)

by Reed Ueda (no photo)Synopsis

"A Companion to American Immigration" is an authoritative collection of original essays by leading scholars on the major topics and themes underlying American immigration history.Focuses on the two most important periods in American Immigration history: the Industrial Revolution (1820-1930) and the Globalizing Era (Cold War to the present)Provides an in-depth treatment of central themes, including economic circumstances, acculturation, social mobility, and assimilationIncludes an introductory essay by the volume editor.

Immigration Wars: Forging an American Solution

Immigration Wars: Forging an American Solution by Jeb Bush (no photo)

by Jeb Bush (no photo)Synopsis:

The immigration debate has challenged our nation since its founding. But today, it divides Americans more stridently than ever, due to a chronic failure of national leadership by both parties. Here at last is an attainable resolution guided by two core principles: first, immigration is vital to America’s future; second, any enduring resolution must adhere to the rule of law.

Unfortunately, current laws are so cumbersome and irrational that millions have circumvented them and entered the United States illegally, taxing our system to the breaking point. Jeb Bush and Clint Bolick contend there are other unique factors currently at play: America’s future population expansion will come solely from immigrants. And for the first time, the U.S. must compete with other countries for immigrant workers and their skills.

In the first book to offer a practical, nonpartisan approach, Bush and Bolick propose a compelling six-point strategy for reworking our policies that begins with erasing all existing, outdated immigration structures and starting over. From there, Immigration Wars details their plan for advancing the national goals that immigration policy is supposed to achieve: build a demand-driven immigration system; increase states’ autonomy based on varying needs; reduce the significant physical risks and financial costs imposed by illegal immigration; unite Mexico and America in their common war against drug cartels; and educate aspiring citizens in our nation’s founding principles and why they still matter.

Here too is a viable variation of the DREAM Act as a legal status for children brought here illegally, and sound strategies for the Republican Party to revitalize their ever-decreasing core constituency.

With Immigration Wars as a beacon of hope, Americans can finally solidify a national identity that is based on a set of ideals enriched and reinvigorated by immigrants, most of whom fervently embrace our core values—family, faith, hard work, education, and patriotism.

I used to teach children who were brought to this country by their parents. Believe me, it wasn't the kids idea. I feel strongly that these kids should not be punished for their parents' decisions They have much to contribute.

I used to teach children who were brought to this country by their parents. Believe me, it wasn't the kids idea. I feel strongly that these kids should not be punished for their parents' decisions They have much to contribute.

1965 Immigration and Nationality Act

1965 Immigration and Nationality ActThe 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act repealed the quota system and set a limit of 20,000 immigrants who could come to the U.S. This basically set an equal ceiling of eligible immigrants from all nations. It led to a decline in European immigrants and a growth in Asian, Indian, and Latin American immigrants. Today 80 percent of foreign-born people in the U.S. are either Asian, African, or Latino.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivnWX...

Source: Youtube

Three Decades of Mass Immigration: The Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act

Three Decades of Mass Immigration: The Legacy of the 1965 Immigration ActIntroduction

"This bill we sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not restructure the shape of our daily lives."

So said President Lyndon Johnson at the signing of the Hart-Celler Immigration Bill thirty years ago next month, on Oct. 3, 1965. The legislation, which phased out the national origins quota system first instituted in 1921, created the foundation of today's immigration law. And, contrary to the president's assertions, it inaugurated a new era of mass immigration which has affected the lives of millions.

Despite modifications, the framework established by the 1965 act remains intact today. And, while the reform proposals now being discussed in Congress, the administration, and the Commission on Immigration Reform would reduce the total number of legal immigrants, they would maintain the fundamentals of the 1965 act — family reunification and employment preferences. So it behooves us on this 30th anniversary to look at the act and the expectations its sponsors had for it.

Under the old system, admission largely depended upon an immigrant's country of birth. Seventy percent of all immigrant slots were allotted to natives of just three countries — United Kingdom, Ireland and Germany — and went mostly unused, while there were long waiting lists for the small number of visas available to those born in Italy, Greece, Poland, Portugal, and elsewhere in eastern and southern Europe.

The new system eliminated the various nationality criteria, supposedly putting people of all nations on an equal footing for immigration to the United States. The new legislation (P.L. 89 236; 79 Stat. 911; technically, amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952) substituted a system based primarily on family reunification and needed skills.

In the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, President Johnson criticized the old policy at the signing ceremony:

"This system violates the basic principle of American democracy -- the principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man. It has been un-American in the highest sense, because it has been untrue to the faith that brought thousands to these shores even before we were a country." (Johnson, Lyndon B., Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1966, pp. 1037-1040.)

Despite the noble words, the architects of the 1965 law did not see it as a means of significantly changing the immigration flow — it was considered more a symbolic act, an extension of civil rights sentiments beyond our borders. Proponents repeatedly denied that the law would lead to a huge and sustained increase in the number of newcomers and become a vehicle for globalizing immigration. Many senators and representatives believed that the new, equal quotas would not be fully used by European, Asian, and Middle Eastern nations. In addition, they did not foresee the expansion of non-quota admissions (those not covered by numerical limits) under the act's strengthened provisions for family reunification.

The unexpected result has been one of the greatest waves of immigration in the nation's history — more than 18 million legal immigrants since the law's passage, over triple the number admitted during the previous 30 years, as well as uncountable millions of illegal immigrants. And the new immigrants are more likely to stay (rather than return home after a time) than those who came around the turn of the century. Moreover, this new, enlarged immigration flow came from countries in Asia and Latin America which heretofore had sent few of their sons and daughters to the United States. And finally, although the average level of education of immigrants has increased somewhat over the past 30 years, the negative gap between their education and that of native-born Americans has increased significantly, creating a mismatch between newcomers and the needs of a modern, high-tech economy.

This paper offers a brief overview of the issues relating to the anniversary, including quotes from many of the participants, as well as an outline of the law's consequences.

Setting

The liberalization of immigration policy reflected in the 1965 legislation can be understood as part of the evolutionary trend in federal policy after World War II to end legal discrimination based on race and ethnicity — essentially, the immigration bill was mainly seen as an extension of the civil rights movement, and a symbolic one at that, expected to bring few changes in its wake.

In 1957, Congress passed the first civil rights law since Reconstruction, another in 1960, and two important bills in 1964 and 1965. Moreover, Supreme Court decisions and state and local laws also struck at the remnants of legal racism. The immigration bill was merely another step in this process.

The connection between civil rights legislation and abolishing the national origins quotas was explicit. As Rep. Philip Burton (D-CA) said in Congress:

"Just as we sought to eliminate discrimination in our land through the Civil Rights Act, today we seek by phasing out the national origins quota system to eliminate discrimination in immigration to this nation composed of the descendants of immigrants." (Congressional Record, Aug. 25, 1965, p. 21783.)

And Rep. Robert Sweeney (D-OH) said:

"Mr. Chairman, I would consider the amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act to be as important as the landmark legislation of this Congress relating to the Civil Rights Act. The central purpose of the administration's immigration bill is to once again undo discrimination and to revise the standards by which we choose potential Americans in order to be fairer to them and which will certainly be more beneficial to us." (Congressional Record, Aug. 25, 1965, p. 21765.)

Other politicians also thought the immigration law needed to be changed. Much earlier, President Truman, in the message accompanying his (unsuccessful) veto of the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act (which had maintained the national origins quota system), wrote:

"These are only a few examples of the absurdity, the cruelty of carrying over into this year of 1952 the isolationist limitations of our 1924 law. In no other realm of our national life are we so hampered and stultified by the dead hand of the past, as we are in this field of immigration." (Truman, Harry S., Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1961, pp. 443-444.)

In 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared to Congress:

"I again urge the liberalization of some of our restrictions upon immigration...we should double the 154,000 quota immigrants ... we should make special provisions for the absorption of many thousands of persons who are refugees." (Eisenhower, Dwight D., Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1961, pp. 308-310.)

President John F. Kennedy's immigration message to Congress on July 23, 1963, assailed the national origins quota system as having "no basis in either logic or reason." He complained,

"It neither satisfies a national need nor accomplishes an international purpose. In an age of interdependence among nations, such a system is an anachronism for it discriminates among applicants for admission into the United States on the basis of the accident of birth." (Kennedy, John F., Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1964, pp. 594-597.)

Foreign policy concerns also motivated some to support change in the national origins system. With the decolonization of Africa and Asia, and with ongoing competition with the Soviet Union for the hearts and minds of the developing world, the quota system was seen as an embarrassment. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, for instance, said the existing immigration law stood in contrast to the growth of refugee legislation aimed at forming international linkages and having "the respect of people all around the world." (Congressional Record, June 27, 1952, p. 8267.)

Others favored a change in the law for more personal reasons — they had relatives who were on long immigration waiting lists because of small quotas for their countries. Italy, for instance, had an annual quota of 5,666 immigrants, Greece 308, Poland 6,488, Yugoslavia 942, and so on. Joseph Errigo, National Chairman of the Sons of Italy Committee on Immigration, was upset at the small size of Italy's quota and urged Congress to "abolish a system which is gradually becoming unpopular and inoperative." Italy had 249,583 people waiting for admission into the United States. (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D.C., Feb. 10, 1965, p. 407.)

Details

The Hart-Celler Act of 1965:

Established the basic structure of today's immigration law.

Abolished the national origins quota system (originally established in 1921 and most recently modified in 1952), while attempting to keep immigration to a manageable level. Family reunification became the cornerstone of U.S. immigration policy.

Allocated 170,000 visas to countries in the Eastern Hemisphere and 120,000 to countries in the Western Hemisphere. This increased the annual ceiling on immigrants from 150,000 to 290,000. Each Eastern-Hemisphere country was allowed an allotment of 20,000 visas, while in the Western Hemisphere there was no per-country limit. This was the first time any numerical limitation had been placed on immigration from the Western Hemisphere. Non-quota immigrants and immediate relatives (i.e., spouses, minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens over the age of 21) were not to be counted as part of either the hemispheric or country ceiling.

For the first time, gave higher preference to the relatives of American citizens and permanent resident aliens than to applicants with special job skills. The preference system for visa admissions detailed in the law (modified in 1990) was as follows:

Unmarried adult sons and daughters of U.S. citizens.

Spouses and children and unmarried sons and daughters of permanent resident aliens.

Members of the professions and scientists and artists of exceptional ability.

Married children of U.S. citizens.

Brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens over age twenty-one.

Skilled and unskilled workers in occupations for which there is insufficient labor supply.

Refugees given conditional entry or adjustment — chiefly people from Communist countries and the Middle East.

Applicants not entitled to preceding preferences — i.e., everyone else.

See Source for complete article.

Source: Center of Immigration Studies

The Law that Changed the Face of America: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Law that Changed the Face of America: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965(no image) The Law that Changed the Face of America: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 by Margaret Sands Orchowski (no photo)

Synopsis:

2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1965—a landmark decision that made the United State the diverse nation it is today. The INA’s importance and impact on the country at rivals that of the Civil and Voting Rights Acts of 1964, that have been celebrated, analyzed and extolled by books and events throughout the country this year. In The Law that Changed the Face of America, Congressional journalist and immigration expert Margaret Sands Orchowski delivers a never before told story of how immigration laws have moved in constant flux and revision throughout our nation’s history. The book uses interviews and historical research to narrate without agenda the personal stories and incentives of those who shaped and fought for the INA. Exploring the changing immigration environment of the 21st century, Orchowski discusses globalization, technology, terrorism, economic recession, and the expectations of the millennials. She also addresses the ever present U.S. debate about the roles of the various branches of government in immigration; and the often competitive interests between those who want to immigrate into the U.S and the changing interests, values, ability, and right of our sovereign nation states to choose and welcome those immigrants who will best advance the country.

This Land Is Our Land: A History of American Immigration

This Land Is Our Land: A History of American ImmigrationUpcoming Book

Release Date April 12, 2016

by Linda Barrett Osborne (no photo)

by Linda Barrett Osborne (no photo)Synopsis:

American attitudes toward immigrants are paradoxical. On the one hand, we see our country as a haven for the poor and oppressed; anyone, no matter his or her background, can find freedom here and achieve the “American Dream.” On the other hand, depending on prevailing economic conditions, fluctuating feelings about race and ethnicity, and fear of foreign political and labor agitation, we set boundaries and restrictions on who may come to this country and whether they may stay as citizens. This book explores the way government policy and popular responses to immigrant groups evolved throughout U.S. history, particularly between 1800 and 1965. The book concludes with a summary of events up to contemporary times, as immigration again becomes a hot-button issue. Includes an author’s note, bibliography, and index.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)

by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)Synopsis:

Along with the civil rights and voting rights acts, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 is one of the most important bills of the civil rights era. The Act's political, legal, and demographic impact continues to be felt, yet its legacy is controversial.

The 1965 Act was groundbreaking in eliminating the white America immigration policy in place since 1790, ending Asian exclusion, and limiting discrimination against Eastern European Catholics and Jews. At the same time, the Act discriminated against gay men and lesbians, tied refugee status to Cold War political interests, and shattered traditional patterns of Mexican migration, setting the stage for current immigration politics. Drawing from studies in law, political science, anthropology, and economics, this book will be an essential tool for any scholar or student interested in immigration law.

Immigrant Struggles, Immigrant Gifts

Immigrant Struggles, Immigrant Gifts by Diane Portnoy (no photo)

by Diane Portnoy (no photo)Synopsis:

The latest book from the Immigrant Learning Center addresses some of the most prominent immigrant groups and the most striking episodes of nativism in American history. The introduction covers American immigration history and law as they have developed since the late eighteenth century. The essays that follow--authored by historians, sociologists, and anthropologists--examine the experiences of a large variety of populations to discover patterns in both immigration and anti-immigrant sentiment. The numerous cases reveal much about the immigrants' motivations for leaving their home countries, the obstacles they face to advancement and inclusion, their culture and occupational trends in the United States, their assimilation and acculturation, and their accomplishments and contributions to American life.

1965 Immigration Law Changed Face of America May 9, 2006

As Congress considers sweeping changes to immigration law, nearly all the debate has centered on the problem of illegal immigration. Little discussed are the many concerns of legal immigrants, the estimated 3 million to 4 million who are, as it's so often been put —"already standing in line."

The current system of legal immigration dates to 1965. It marked a radical break with previous policy and has led to profound demographic changes in America. But that's not how the law was seen when it was passed — at the height of the civil rights movement, at a time when ideals of freedom, democracy and equality had seized the nation. Against this backdrop, the manner in which the United States decided which foreigners could and could not enter the country had become an increasing embarrassment.

An Argument Based on Egalitarianism

"The law was just unbelievable in its clarity of racism," says Stephen Klineberg, a sociologist at Rice University. "It declared that Northern Europeans are a superior subspecies of the white race. The Nordics were superior to the Alpines, who in turn were superior to the Mediterraneans, and all of them were superior to the Jews and the Asians."

President Lyndon B. Johnson (center) signs the sweeping immigration bill of 1965 into law at a ceremony on Liberty Island, Oct. 4, 1965. Sen. Edward Kennedy and his brother, Sen. Robert Kennedy, are seen at right.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

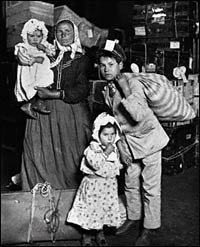

An Italian woman and her children arrive at Ellis Island in 1905. Italians were among those who complained that U.S. immigration laws discriminated against them. Since 1965, family-based immigration has driven profound demographic shifts in America.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

By the 1960s, Greeks, Poles, Portuguese and Italians were complaining that immigration quotas discriminated against them in favor of Western Europeans. The Democratic Party took up their cause, led by President John F. Kennedy. In a June 1963 speech to the American Committee on Italian Migration, Kennedy called the system of quotas in place back then " nearly intolerable."

After Kennedy's assassination, Congress passed, and President Lyndon Johnson, signed the Immigration and Naturalization Act. It leveled the immigration playing field, giving a nearly equal shot to newcomers from every corner of the world. The ceremony was held at the foot of the symbolically powerful Statue of Liberty. Yet President Johnson tried to downplay the law's significance.

"This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions," Johnson said at the signing ceremony. "It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives or add importantly to either our wealth or our power."

Looking back, Johnson's statement is remarkable because it proved so wrong. Why? Sociologist Klineberg says the government's newfound sense of egalitarianism only went so far. The central purpose of the new immigration law was to reunite families.

Klineberg notes that in debating an overhaul of immigration policy in the 1960s, many in Congress had argued that little would change because the measure gave preference to relatives of immigrants already in America. Another provision gave preference to professionals with skills in short supply in the United States.

"Congress was saying in its debates, 'We need to open the door for some more British doctors, some more German engineers,'" Klineberg says. "It never occurred to anyone, literally, that there were going to be African doctors, Indian engineers, Chinese computer programmers who'd be able, for the first time in the 20th century, to immigrate to America."

Predictions Based on Ignorance?

In fact, expert after expert testified before Congress that little would change. Secretary of State Dean Rusk repeatedly stressed that the number of new immigrants coming to the United States was not expected to skyrocket. What was really at stake, Rusk argued, was the principle of a more open immigration policy.

When asked about the number of people from India who would want to immigrate to the United States, Rusk told the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization: "The present estimate, based upon the best information we can get, is that there might be, say, 8,000 immigrants from India in the next five years. In other words, I don't think we have a particular picture of a world situation where everybody is just straining to move to the Unites States."

Historian Otis Graham, professor emeritus of the University of California at Santa Barbara, says that when he first started studying the 1965 immigration law, he assumed that politicians at the time had lied about the law's potential consequences in order to get it passed. But he says he has since changed his mind.

"In the research of my students, and in the research I've been able to do," Graham says, "so many lobbyists that followed this issue, so many labor-union executives that followed this issue, so many church people — so many of those involved said the same thing. So you find ignorance three-feet deep. Maybe ignorance is the answer."

Karen Narasaki, who heads the Asian American Justice Center, finds the 1965 immigration overhaul all the more extraordinary because there's evidence it was not popular with the public.

"It was not what people were marching in the streets over in the 1960s," she says. "It was really a group of political elites who were trying to look into the future. And again, it was the issue of, 'Are we going to be true to what we say our values are?'"

In 1965, the political elite on Capitol Hill may not have predicted a mass increase in immigration. But Marian Smith, the historian for Customs and Immigration Services, showed me a small agency booklet from 1966 that certainly did. It explains how each provision in the new law would lead to a rapid increase in applications and a big jump in workload — more and more so as word trickled out to those newly eligible to come. Smith says a lifetime of immigration backlogs had built up among America's foreign-born minorities. These immigrants would petition for relatives to come to the United States, and those relatives in turn would petition for other family members. Demand from post-colonial countries in Asia and Africa, she notes, jumped after World War II.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/st...

Other:

Link to NPR podcast: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/st...

Discussion Topics:

a) Discuss the pros and cons of family-based immigration versus skill-based immigration.

b) Discuss the effects of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Source: National Public Radio

As Congress considers sweeping changes to immigration law, nearly all the debate has centered on the problem of illegal immigration. Little discussed are the many concerns of legal immigrants, the estimated 3 million to 4 million who are, as it's so often been put —"already standing in line."

The current system of legal immigration dates to 1965. It marked a radical break with previous policy and has led to profound demographic changes in America. But that's not how the law was seen when it was passed — at the height of the civil rights movement, at a time when ideals of freedom, democracy and equality had seized the nation. Against this backdrop, the manner in which the United States decided which foreigners could and could not enter the country had become an increasing embarrassment.

An Argument Based on Egalitarianism

"The law was just unbelievable in its clarity of racism," says Stephen Klineberg, a sociologist at Rice University. "It declared that Northern Europeans are a superior subspecies of the white race. The Nordics were superior to the Alpines, who in turn were superior to the Mediterraneans, and all of them were superior to the Jews and the Asians."

President Lyndon B. Johnson (center) signs the sweeping immigration bill of 1965 into law at a ceremony on Liberty Island, Oct. 4, 1965. Sen. Edward Kennedy and his brother, Sen. Robert Kennedy, are seen at right.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

An Italian woman and her children arrive at Ellis Island in 1905. Italians were among those who complained that U.S. immigration laws discriminated against them. Since 1965, family-based immigration has driven profound demographic shifts in America.

© Bettmann/CORBIS

By the 1960s, Greeks, Poles, Portuguese and Italians were complaining that immigration quotas discriminated against them in favor of Western Europeans. The Democratic Party took up their cause, led by President John F. Kennedy. In a June 1963 speech to the American Committee on Italian Migration, Kennedy called the system of quotas in place back then " nearly intolerable."

After Kennedy's assassination, Congress passed, and President Lyndon Johnson, signed the Immigration and Naturalization Act. It leveled the immigration playing field, giving a nearly equal shot to newcomers from every corner of the world. The ceremony was held at the foot of the symbolically powerful Statue of Liberty. Yet President Johnson tried to downplay the law's significance.

"This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions," Johnson said at the signing ceremony. "It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives or add importantly to either our wealth or our power."

Looking back, Johnson's statement is remarkable because it proved so wrong. Why? Sociologist Klineberg says the government's newfound sense of egalitarianism only went so far. The central purpose of the new immigration law was to reunite families.

Klineberg notes that in debating an overhaul of immigration policy in the 1960s, many in Congress had argued that little would change because the measure gave preference to relatives of immigrants already in America. Another provision gave preference to professionals with skills in short supply in the United States.

"Congress was saying in its debates, 'We need to open the door for some more British doctors, some more German engineers,'" Klineberg says. "It never occurred to anyone, literally, that there were going to be African doctors, Indian engineers, Chinese computer programmers who'd be able, for the first time in the 20th century, to immigrate to America."

Predictions Based on Ignorance?

In fact, expert after expert testified before Congress that little would change. Secretary of State Dean Rusk repeatedly stressed that the number of new immigrants coming to the United States was not expected to skyrocket. What was really at stake, Rusk argued, was the principle of a more open immigration policy.

When asked about the number of people from India who would want to immigrate to the United States, Rusk told the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization: "The present estimate, based upon the best information we can get, is that there might be, say, 8,000 immigrants from India in the next five years. In other words, I don't think we have a particular picture of a world situation where everybody is just straining to move to the Unites States."

Historian Otis Graham, professor emeritus of the University of California at Santa Barbara, says that when he first started studying the 1965 immigration law, he assumed that politicians at the time had lied about the law's potential consequences in order to get it passed. But he says he has since changed his mind.

"In the research of my students, and in the research I've been able to do," Graham says, "so many lobbyists that followed this issue, so many labor-union executives that followed this issue, so many church people — so many of those involved said the same thing. So you find ignorance three-feet deep. Maybe ignorance is the answer."

Karen Narasaki, who heads the Asian American Justice Center, finds the 1965 immigration overhaul all the more extraordinary because there's evidence it was not popular with the public.

"It was not what people were marching in the streets over in the 1960s," she says. "It was really a group of political elites who were trying to look into the future. And again, it was the issue of, 'Are we going to be true to what we say our values are?'"

In 1965, the political elite on Capitol Hill may not have predicted a mass increase in immigration. But Marian Smith, the historian for Customs and Immigration Services, showed me a small agency booklet from 1966 that certainly did. It explains how each provision in the new law would lead to a rapid increase in applications and a big jump in workload — more and more so as word trickled out to those newly eligible to come. Smith says a lifetime of immigration backlogs had built up among America's foreign-born minorities. These immigrants would petition for relatives to come to the United States, and those relatives in turn would petition for other family members. Demand from post-colonial countries in Asia and Africa, she notes, jumped after World War II.

Read the remainder of the article at: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/st...

Other:

Link to NPR podcast: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/st...

Discussion Topics:

a) Discuss the pros and cons of family-based immigration versus skill-based immigration.

b) Discuss the effects of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Source: National Public Radio

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, abolished an earlier quota system based on national origin and established a new immigration policy based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor to the United States. Over the next four decades, the policies put into effect in 1965 would greatly change the demographic makeup of the American population, as immigrants entering the United States under the new legislation came increasingly from countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, as opposed to Europe.

IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION ACT OF 1965

By the early 1960s, calls to reform U.S. immigration policy had mounted, thanks in no small part to the growing strength of the civil rights movement. At the time, immigration was based on the national-origins quota system in place since the 1920s, under which each nationality was assigned a quota based on its representation in past U.S. census figures. The civil rights movement’s focus on equal treatment regardless of race or nationality led many to view the quota system as backward and discriminatory. In particular, Greeks, Poles, Portuguese and Italians–of whom increasing numbers were seeking to enter the U.S.–claimed that the quota system discriminated against them in favor of Northern Europeans. President John F. Kennedy even took up the immigration reform cause, giving a speech in June 1963 calling the quota system “intolerable.”

After Kennedy’s assassination that November, Congress began debating and would eventually pass the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, co-sponsored by Representative Emanuel Celler of New York and Senator Philip Hart of Michigan and heavily supported by the late president’s brother, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. During Congressional debates, a number of experts testified that little would effectively change under the reformed legislation, and it was seen more as a matter of principle to have a more open policy. Indeed, on signing the act into law in October 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson stated that the act “is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions….It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives or add importantly to either our wealth or our power.”

IMMEDIATE IMPACT

In reality (and with the benefit of hindsight), the bill signed in 1965 marked a dramatic break with past immigration policy, and would have an immediate and lasting impact. In place of the national-origins quota system, the act provided for preferences to be made according to categories, such as relatives of U.S. citizens or permanent residents, those with skills deemed useful to the United States or refugees of violence or unrest. Though it abolished quotas per se, the system did place caps on per-country and total immigration, as well as caps on each category. As in the past, family reunification was a major goal, and the new immigration policy would increasingly allow entire families to uproot themselves from other countries and reestablish their lives in the U.S.

In the first five years after the bill’s passage, immigration to the U.S. from Asian countries–especially those fleeing war-torn Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia)–would more than quadruple. (Under past immigration policies, Asian immigrants had been effectively barred from entry.) Other Cold War-era conflicts during the 1960s and 1970s saw millions of people fleeing poverty or the hardships of communist regimes in Cuba, Eastern Europe and elsewhere to seek their fortune on American shores. All told, in the three decades following passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, more than 18 million legal immigrants entered the United States, more than three times the number admitted over the preceding 30 years.

By the end of the 20th century, the policies put into effect by the Immigration Act of 1965 had greatly changed the face of the American population. Whereas in the 1950s, more than half of all immigrants were Europeans and just 6 percent were Asians, by the 1990s only 16 percent were Europeans and 31 percent were of Asian descent, while the percentages of Latino and African immigrants had also jumped significantly. Between 1965 and 2000, the highest number of immigrants (4.3 million) to the U.S. came from Mexico, in addition to some 1.4 million from the Philippines. Korea, the Dominican Republic, India, Cuba and Vietnam were also leading sources of immigrants, each sending between 700,000 and 800,000 over this period.

CONTINUING SOURCE OF DEBATE

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, illegal immigration was a constant source of political debate, as immigrants continue to pour into the United States, mostly by land routes through Canada and Mexico. The Immigration Reform Act in 1986 attempted to address the issue by providing better enforcement of immigration policies and creating more possibilities to seek legal immigration. The act included two amnesty programs for unauthorized aliens, and collectively granted amnesty to more than 3 million illegal aliens. Another piece of immigration legislation, the 1990 Immigration Act, modified and expanded the 1965 act, increasing the total level of immigration to 700,000. The law also provided for the admission of immigrants from “underrepresented” countries to increase the diversity of the immigrant flow.

The economic recession that hit the country in the early 1990s was accompanied by a resurgence of anti-immigrant feeling, including among lower-income Americans competing for jobs with immigrants willing to work for lower wages. In 1996, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which addressed border enforcement and the use of social programs by immigrants.

IMMIGRATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which took over many immigration service and enforcement functions formerly performed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). With some modifications, the policies put into place by the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 are the same ones governing U.S. immigration in the early 21st century. Non-citizens currently enter the United States lawfully in one of two ways, either by receiving either temporary (non-immigrant) admission or permanent (immigrant) admission. A member of the latter category is classified as a lawful permanent resident, and receives a green card granting them eligibility to work in the United States and to eventually apply for citizenship.

There could be perhaps no greater reflection of the impact of immigration than the 2008 election of Barack Obama, the son of a Kenyan father and an American mother (from Kansas), as the nation’s first African-American president. Eighty-five percent white in 1965, the nation’s population was one-third minority in 2009 and is on track for a nonwhite majority by 2042.

Link to the article: http://www.history.com/topics/us-immi...

Link to video: http://www.history.com/topics/us-immi...

Other:

by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)

by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)

Source: The History Channel

The Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, abolished an earlier quota system based on national origin and established a new immigration policy based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor to the United States. Over the next four decades, the policies put into effect in 1965 would greatly change the demographic makeup of the American population, as immigrants entering the United States under the new legislation came increasingly from countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, as opposed to Europe.

IMMIGRATION AND NATURALIZATION ACT OF 1965

By the early 1960s, calls to reform U.S. immigration policy had mounted, thanks in no small part to the growing strength of the civil rights movement. At the time, immigration was based on the national-origins quota system in place since the 1920s, under which each nationality was assigned a quota based on its representation in past U.S. census figures. The civil rights movement’s focus on equal treatment regardless of race or nationality led many to view the quota system as backward and discriminatory. In particular, Greeks, Poles, Portuguese and Italians–of whom increasing numbers were seeking to enter the U.S.–claimed that the quota system discriminated against them in favor of Northern Europeans. President John F. Kennedy even took up the immigration reform cause, giving a speech in June 1963 calling the quota system “intolerable.”

After Kennedy’s assassination that November, Congress began debating and would eventually pass the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, co-sponsored by Representative Emanuel Celler of New York and Senator Philip Hart of Michigan and heavily supported by the late president’s brother, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. During Congressional debates, a number of experts testified that little would effectively change under the reformed legislation, and it was seen more as a matter of principle to have a more open policy. Indeed, on signing the act into law in October 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson stated that the act “is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions….It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives or add importantly to either our wealth or our power.”

IMMEDIATE IMPACT

In reality (and with the benefit of hindsight), the bill signed in 1965 marked a dramatic break with past immigration policy, and would have an immediate and lasting impact. In place of the national-origins quota system, the act provided for preferences to be made according to categories, such as relatives of U.S. citizens or permanent residents, those with skills deemed useful to the United States or refugees of violence or unrest. Though it abolished quotas per se, the system did place caps on per-country and total immigration, as well as caps on each category. As in the past, family reunification was a major goal, and the new immigration policy would increasingly allow entire families to uproot themselves from other countries and reestablish their lives in the U.S.

In the first five years after the bill’s passage, immigration to the U.S. from Asian countries–especially those fleeing war-torn Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia)–would more than quadruple. (Under past immigration policies, Asian immigrants had been effectively barred from entry.) Other Cold War-era conflicts during the 1960s and 1970s saw millions of people fleeing poverty or the hardships of communist regimes in Cuba, Eastern Europe and elsewhere to seek their fortune on American shores. All told, in the three decades following passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, more than 18 million legal immigrants entered the United States, more than three times the number admitted over the preceding 30 years.

By the end of the 20th century, the policies put into effect by the Immigration Act of 1965 had greatly changed the face of the American population. Whereas in the 1950s, more than half of all immigrants were Europeans and just 6 percent were Asians, by the 1990s only 16 percent were Europeans and 31 percent were of Asian descent, while the percentages of Latino and African immigrants had also jumped significantly. Between 1965 and 2000, the highest number of immigrants (4.3 million) to the U.S. came from Mexico, in addition to some 1.4 million from the Philippines. Korea, the Dominican Republic, India, Cuba and Vietnam were also leading sources of immigrants, each sending between 700,000 and 800,000 over this period.

CONTINUING SOURCE OF DEBATE

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, illegal immigration was a constant source of political debate, as immigrants continue to pour into the United States, mostly by land routes through Canada and Mexico. The Immigration Reform Act in 1986 attempted to address the issue by providing better enforcement of immigration policies and creating more possibilities to seek legal immigration. The act included two amnesty programs for unauthorized aliens, and collectively granted amnesty to more than 3 million illegal aliens. Another piece of immigration legislation, the 1990 Immigration Act, modified and expanded the 1965 act, increasing the total level of immigration to 700,000. The law also provided for the admission of immigrants from “underrepresented” countries to increase the diversity of the immigrant flow.

The economic recession that hit the country in the early 1990s was accompanied by a resurgence of anti-immigrant feeling, including among lower-income Americans competing for jobs with immigrants willing to work for lower wages. In 1996, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which addressed border enforcement and the use of social programs by immigrants.

IMMIGRATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which took over many immigration service and enforcement functions formerly performed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). With some modifications, the policies put into place by the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 are the same ones governing U.S. immigration in the early 21st century. Non-citizens currently enter the United States lawfully in one of two ways, either by receiving either temporary (non-immigrant) admission or permanent (immigrant) admission. A member of the latter category is classified as a lawful permanent resident, and receives a green card granting them eligibility to work in the United States and to eventually apply for citizenship.

There could be perhaps no greater reflection of the impact of immigration than the 2008 election of Barack Obama, the son of a Kenyan father and an American mother (from Kansas), as the nation’s first African-American president. Eighty-five percent white in 1965, the nation’s population was one-third minority in 2009 and is on track for a nonwhite majority by 2042.

Link to the article: http://www.history.com/topics/us-immi...

Link to video: http://www.history.com/topics/us-immi...

Other:

by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)

by Gabriel J. Chin (no photo)Source: The History Channel

Fifty Years On, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act Continues to Reshape the United States

By MUZAFFAR CHISHTI, FAYE HIPSMAN, ISABEL BALL October 15, 2015

President Lyndon B. Johnson prepares to sign the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 at the foot of the Statue of Liberty on October 3, 1965. (Photo: Yoichi Okamoto/LBJ Library)

October 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Signed into law at the foot of the Statue of Liberty by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the act ushered in far-reaching changes that continue to undergird the current immigration system, and set in motion powerful demographic forces that are still shaping the United States today and will in the decades ahead.

The law, known as the Hart-Celler Act for its congressional sponsors, literally changed the face of America. It ended an immigration-admissions policy based on race and ethnicity, and gave rise to large-scale immigration, both legal and unauthorized. While the anniversary has provided an opportunity to reflect on the law’s historic significance, it also reminds us that the ’65 Act holds important lessons for policymaking today.

The Significance of the 1965 Act, Then and Now

The historic significance of the 1965 law was to repeal national-origins quotas, in place since the 1920s, which had ensured that immigration to the United States was primarily reserved for European immigrants. The 1921 national-origins quota law was enacted in a special congressional session after President Wilson’s pocket veto. Along with earlier and other contemporary statutory bars to immigration from Asian countries, the quotas were proposed at a time when eugenics theories were widely accepted. The quota for each country was set at 2 percent of the foreign-born population of that nationality as enumerated in the 1890 census. The formula was designed to favor Western and Northern European countries and drastically limit admission of immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Southern and Eastern Europe. In major revisions to U.S. immigration law in 1952, the national-origins system was retained, despite a strong veto message by President Truman.

Building on a campaign promise by President Kennedy, and with a strong push by President Johnson amid the enactment of other major civil-rights legislation, the 1965 law abolished the national-origins quota system. It was replaced with a preference system based on immigrants’ family relationships with U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents and, to a lesser degree, their skills. The law placed an annual cap of 170,000 visas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere, with no single country allowed more than 20,000 visas, and for the first time established a cap of 120,000 visas for immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. Three-fourths of admissions were reserved for those arriving in family categories. Immediate relatives (spouses, minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens) were exempt from the caps; 24 percent of family visas were assigned to siblings of U.S. citizens. In 1976, the 20,000 per county limit was applied to the Western Hemisphere. And in 1978, a worldwide immigrant visa quota was set at 290,000.

Though ratified half a century ago, the Hart-Celler framework still defines today’s legal immigration system. Under current policy, there are five family-based admissions categories, ranked in preference based on the family relationship, and capped at 480,000 visas (again, exempting immediate relatives of U.S. citizens), and five employment-based categories capped at 140,000 visas. Smaller numbers are admitted through refugee protection channels and the Diversity Visa Lottery—a program designed to bring immigrants from countries that are underrepresented in U.S. immigration streams, partly as a consequence of the 1965 Act. Though Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1990 to admit a greater share of highly skilled and educated immigrants through employment channels, family-based immigrants continue to comprise two-thirds of legal immigration, while about 15 percent of immigrants become permanent residents through their employers.

Unintended Consequences

Much of the sweeping impact of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act was the result of unintended consequences. "The bill that we sign today is not a revolutionary bill," President Johnson said during the signing ceremony. “It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power.” Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), the bill’s floor manager, stated: "It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society." Even advocacy groups who had favored the national-origins quotas became supporters, predicting little change to the profile of immigration streams.

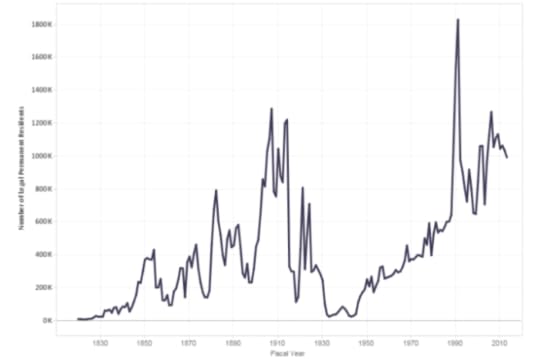

Despite these predictions, the measure had a profound effect on the flow of immigrants to the United States, and in only a matter of years began to transform the U.S. demographic profile. The number of new lawful permanent residents (or green-card holders) rose from 297,000 in 1965 to an average of about 1 million each year since the mid-2000s (see Figure 1). Accordingly, the foreign-born population has risen from 9.6 million in 1965 to a record high of 45 million in 2015 as estimated by a new study from the Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project. Immigrants accounted for just 5 percent of the U.S. population in 1965 and now comprise 14 percent.

A second unintended consequence of the law stemmed largely from a political compromise clearly intended to have the opposite effect. The original bill provided a preference for immigrants with needed skills and education. But a group of influential congressmen (conservatives allied with the Democratic chairman of the House immigration subcommittee) won a last-minute concession to prioritize admission of immigrants with family members already in the United States, believing it would better preserve the country’s predominantly Anglo-Saxon, European base. In the following years, however, demand from Europeans to immigrate to the United States fell flat while interest from non-European countries—many emerging from the end of colonial rule—began to grow. New and well-educated immigrants from diverse countries in Asia and Latin America established themselves in the United States and became the foothold for subsequent immigration by their family networks.

Compared to almost entirely European immigration under the national-origins system, flows since 1965 have been more than half Latin American and one-quarter Asian. The largest share of today’s immigrant population, about 11.6 million, is from Mexico. Together with India, the Philippines, China, Vietnam, El Salvador, Cuba, South Korea, the Dominican Republic, and Guatemala, these ten countries account for nearly 60 percent of the current immigrant population.

Link to remainder of article: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/artic...

Link to videotape: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-a9P...

Other:

by AILA (no photo)

by AILA (no photo)

Source: Migration Policy Institute

By MUZAFFAR CHISHTI, FAYE HIPSMAN, ISABEL BALL October 15, 2015

President Lyndon B. Johnson prepares to sign the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 at the foot of the Statue of Liberty on October 3, 1965. (Photo: Yoichi Okamoto/LBJ Library)

October 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Signed into law at the foot of the Statue of Liberty by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the act ushered in far-reaching changes that continue to undergird the current immigration system, and set in motion powerful demographic forces that are still shaping the United States today and will in the decades ahead.

The law, known as the Hart-Celler Act for its congressional sponsors, literally changed the face of America. It ended an immigration-admissions policy based on race and ethnicity, and gave rise to large-scale immigration, both legal and unauthorized. While the anniversary has provided an opportunity to reflect on the law’s historic significance, it also reminds us that the ’65 Act holds important lessons for policymaking today.

The Significance of the 1965 Act, Then and Now

The historic significance of the 1965 law was to repeal national-origins quotas, in place since the 1920s, which had ensured that immigration to the United States was primarily reserved for European immigrants. The 1921 national-origins quota law was enacted in a special congressional session after President Wilson’s pocket veto. Along with earlier and other contemporary statutory bars to immigration from Asian countries, the quotas were proposed at a time when eugenics theories were widely accepted. The quota for each country was set at 2 percent of the foreign-born population of that nationality as enumerated in the 1890 census. The formula was designed to favor Western and Northern European countries and drastically limit admission of immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Southern and Eastern Europe. In major revisions to U.S. immigration law in 1952, the national-origins system was retained, despite a strong veto message by President Truman.

Building on a campaign promise by President Kennedy, and with a strong push by President Johnson amid the enactment of other major civil-rights legislation, the 1965 law abolished the national-origins quota system. It was replaced with a preference system based on immigrants’ family relationships with U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents and, to a lesser degree, their skills. The law placed an annual cap of 170,000 visas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere, with no single country allowed more than 20,000 visas, and for the first time established a cap of 120,000 visas for immigrants from the Western Hemisphere. Three-fourths of admissions were reserved for those arriving in family categories. Immediate relatives (spouses, minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens) were exempt from the caps; 24 percent of family visas were assigned to siblings of U.S. citizens. In 1976, the 20,000 per county limit was applied to the Western Hemisphere. And in 1978, a worldwide immigrant visa quota was set at 290,000.

Though ratified half a century ago, the Hart-Celler framework still defines today’s legal immigration system. Under current policy, there are five family-based admissions categories, ranked in preference based on the family relationship, and capped at 480,000 visas (again, exempting immediate relatives of U.S. citizens), and five employment-based categories capped at 140,000 visas. Smaller numbers are admitted through refugee protection channels and the Diversity Visa Lottery—a program designed to bring immigrants from countries that are underrepresented in U.S. immigration streams, partly as a consequence of the 1965 Act. Though Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1990 to admit a greater share of highly skilled and educated immigrants through employment channels, family-based immigrants continue to comprise two-thirds of legal immigration, while about 15 percent of immigrants become permanent residents through their employers.

Unintended Consequences

Much of the sweeping impact of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act was the result of unintended consequences. "The bill that we sign today is not a revolutionary bill," President Johnson said during the signing ceremony. “It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives, or really add importantly to either our wealth or our power.” Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), the bill’s floor manager, stated: "It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society." Even advocacy groups who had favored the national-origins quotas became supporters, predicting little change to the profile of immigration streams.

Despite these predictions, the measure had a profound effect on the flow of immigrants to the United States, and in only a matter of years began to transform the U.S. demographic profile. The number of new lawful permanent residents (or green-card holders) rose from 297,000 in 1965 to an average of about 1 million each year since the mid-2000s (see Figure 1). Accordingly, the foreign-born population has risen from 9.6 million in 1965 to a record high of 45 million in 2015 as estimated by a new study from the Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends Project. Immigrants accounted for just 5 percent of the U.S. population in 1965 and now comprise 14 percent.

A second unintended consequence of the law stemmed largely from a political compromise clearly intended to have the opposite effect. The original bill provided a preference for immigrants with needed skills and education. But a group of influential congressmen (conservatives allied with the Democratic chairman of the House immigration subcommittee) won a last-minute concession to prioritize admission of immigrants with family members already in the United States, believing it would better preserve the country’s predominantly Anglo-Saxon, European base. In the following years, however, demand from Europeans to immigrate to the United States fell flat while interest from non-European countries—many emerging from the end of colonial rule—began to grow. New and well-educated immigrants from diverse countries in Asia and Latin America established themselves in the United States and became the foothold for subsequent immigration by their family networks.

Compared to almost entirely European immigration under the national-origins system, flows since 1965 have been more than half Latin American and one-quarter Asian. The largest share of today’s immigrant population, about 11.6 million, is from Mexico. Together with India, the Philippines, China, Vietnam, El Salvador, Cuba, South Korea, the Dominican Republic, and Guatemala, these ten countries account for nearly 60 percent of the current immigrant population.

Link to remainder of article: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/artic...

Link to videotape: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-a9P...

Other:

by AILA (no photo)

by AILA (no photo)Source: Migration Policy Institute

The Immigration Act That Inadvertently Changed America

Fifty years after its passage, it’s clear that the law’s ultimate effects are at odds with its original intent.

By TOM GJELTEN October 2, 2015

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration Act on Liberty Island in 1965 (AP)

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, whose 50th anniversary comes on October 3, officially committed the United States, for the first time, to accepting immigrants of all nationalities on a roughly equal basis. The law eliminated the use of national-origin quotas, under which the overwhelming majority of immigrant visas were set aside for people coming from northern and western Europe.

In the subsequent half century, the pattern of U.S. immigration changed dramatically. The share of the U.S. population born outside the country tripled and became far more diverse. Seven out of every eight immigrants in 1960 were from Europe; by 2010, nine out of ten were coming from other parts of the world. The 1965 Immigration Act was largely responsible for that shift. No law passed in the 20th century altered the country’s demographic character quite so thoroughly. But its effects were largely inadvertent. The law’s biggest impact on immigration patterns resulted from provisions meant to thwart its ability to change much at all.

The United States has long struggled to define what it really means to become American and which immigrants qualify. George Washington declared the country was open to “the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions,” but the idea persists that America is a “Judeo-Christian nation,” that being a Muslim American is a contradiction in terms, and that some nationalities are inferior to others.

Such questions should have been settled 50 years ago with the passage of the 1965 Act. For supporters, the intent of the legislation was to bring immigration policy into line with other anti-discrimination measures, not to fundamentally change the face of the nation. “We have removed all elements of second-class citizenship from our laws by the [1964] Civil Rights Act,” declared Vice President Hubert Humphrey. “We must in 1965 remove all elements in our immigration law which suggest there are second-class people.”

At the signing ceremony on Liberty Island, President Lyndon Johnson said the new law “corrects a cruel and enduring wrong in the conduct of the American nation,” but he downplayed its expected effect. “The bill that we sign today is not a revolutionary bill,” he insisted.

Opponents of the reform proposal had argued that the United States was fundamentally a European country and should stay that way. “The people of Ethiopia have the same right to come to the United States under this bill as the people from England, the people of France, the people of Germany, [and] the people of Holland,” complained Senator Sam Ervin, a Democrat from North Carolina. “With all due respect to Ethiopia,” Ervin said, “I don’t know of any contributions that Ethiopia has made to the making of America.” The critics highlighted population pressures in the developing world and predicted the United States would find itself inundated by desperate migrants from poverty-stricken countries.

Link to remainder of article: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/...

Other:

by

by

Kevin R. Johnson

Kevin R. Johnson

Source: The Atlantic

Fifty years after its passage, it’s clear that the law’s ultimate effects are at odds with its original intent.

By TOM GJELTEN October 2, 2015

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration Act on Liberty Island in 1965 (AP)

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, whose 50th anniversary comes on October 3, officially committed the United States, for the first time, to accepting immigrants of all nationalities on a roughly equal basis. The law eliminated the use of national-origin quotas, under which the overwhelming majority of immigrant visas were set aside for people coming from northern and western Europe.

In the subsequent half century, the pattern of U.S. immigration changed dramatically. The share of the U.S. population born outside the country tripled and became far more diverse. Seven out of every eight immigrants in 1960 were from Europe; by 2010, nine out of ten were coming from other parts of the world. The 1965 Immigration Act was largely responsible for that shift. No law passed in the 20th century altered the country’s demographic character quite so thoroughly. But its effects were largely inadvertent. The law’s biggest impact on immigration patterns resulted from provisions meant to thwart its ability to change much at all.

The United States has long struggled to define what it really means to become American and which immigrants qualify. George Washington declared the country was open to “the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions,” but the idea persists that America is a “Judeo-Christian nation,” that being a Muslim American is a contradiction in terms, and that some nationalities are inferior to others.