Theodora Goss's Blog, page 28

February 1, 2013

Being Exhausted

I did such a stupid thing tonight! I put something on the stove, and promptly forgot about it. Of course it started to smoke, which set off the fire alarm. Since I live in faculty housing at the university, my apartment is alarmed in the same way as a university dorm. Do you remember the nights when the dorm fire alarms went off, and we all had to file outside in our pajamas? I’m sure every university student has to go through that at least once. It’s a rite of passage.

The problem was, I couldn’t get the alarm to turn off again. It just kept beeping, in that incredibly loud, industrial, university fire alarm way. There’s a button you can push to turn the alarm off, but it wasn’t working. So I had to call building maintenance. The maintenance man came in about half an hour, but in the meantime, I put Persephone the Cat in the bathroom, which was the quietest part of the apartment, since I didn’t want the alarm to hurt her sensitive ears. And I went out into the hall, to escape from it myself.

That did give me an opportunity to meet my upstairs neighbor, a lovely woman who lives in the beautiful nineteenth-century apartment above me. She’s a Trustee of the university, and a friend of Elie Wiesel, and when she mentioned that she had met Katie Couric at a graduation event, I mentioned that I had met her too, at a cocktail party, since I had worked for the same firm as her husband. (She is much smaller than you would think, but just as perky.) So there was a silver lining to that particular cloud (of smoke).

This experience has led me to formulate a principle for myself: When you’re tired, don’t cook. Make yourself a cheese sandwich, eat a cereal bar, cut up an apple . . . But don’t turn the stove on!

The central problem is that I’m exhausted. There’s just so much work to get done, and it’s going to be like this for the next six weeks or so. After that, I will only be teaching three classes, rather than the current four, and my schedule will get easier. And then the summer will come, and I will be traveling around Europe in my usual way, going wherever I wish, seeing whatever I wish to see, meeting people. That will be lovely . . .

This is all worthwhile, all worth the exhaustion, because I’m in the process of changing my life into the one I want to live. I just have to remember, in the meantime, to take care of myself as much as I can. Which leads me to another principle for myself:

While creating the life you want to live, try not to kill yourself.

I’m tempted to post two pictures that I posted earlier on Facebook. Should I? Yes, I think I will. The first picture is one I took of myself last week. It’s of me completely exhausted, taken in the bathroom mirror.

The second one is of my street in Budapest. Yes, that’s Múzeum Utca, with the park around the Nemzeti Múzeum to the left, and the California Coffee Company on the corner. That’s where I go for my latte and free wifi in the mornings, and for a sour cherry brownie when I’m craving one . . .

I’m in the process of rearranging my schedule and my life, and this is the hard part. But eventually, it will all have been so very worthwhile . . . (I just have to not kill myself in the process.)

January 29, 2013

Being Loved

I think we all fundamentally want the same thing, which is to be loved.

This seems like such an obvious thing to say, and yet I think it’s not obvious at all, partly because we have such a vague sense of what love actually is. We use the word for so many things! I love roses, for example. I love them because they’re beautiful, and because of their scent, and even because they can be so difficult. And I do not love the hybrid teas that to me are not really roses. (You know, the roses that you get on Valentine’s Day, which have long stems and tight buds and are impossible to grow. For me, real roses are the old Gallicas and Albas and Damasks.) If only we loved people the way we love roses, or books, or houses! Books and houses we also love because they are beautiful and difficult. And yet, when we love people, we get frustrated by the difficulty . . .

I think that when we say we want to be loved, what we really mean is that we want to be understood, and accepted, and valued. Understood for who we are, and accepted and valued for that . . . And that’s where the difficulty lies, doesn’t it? Because so often when we love people, we want them to be different. We love them despite, rather than because. And yet, who among us wants to be loved despite? We want to be loved with our thorns, and even because of our thorns.

One of the reasons I’ve only been thinking about this recently is that in my family, we never talked about love. We were supposed to behave in a certain way: to become educated and cultured, to dress properly and act appropriately. The emphasis was always on our accomplishments rather than our relationships. But loving well is a sort of skill, really. Truly understanding, accepting, and valuing another human being is not an easy thing to do. Often love has something else mixed into it, a bit of dislike, a bit of disdain. That small thing will kill it, eventually. Because we can tell when someone does not truly love us, when that love is mixed with something else. We always know, even when we try to hide it from ourselves . . . Loving is something that takes honesty and courage.

It would be easy to love a rose without thorns, a book with no complicated passages, a house in which the windows did not stick in summer. A human being without old hurts or habits that displeased us. But perhaps that would not be love, just a sort of easy pleasure. Perhaps love is in the accepting, in the valuing.

Some time ago, I found a quotation from Jeannette Winterson that struck me. Here it is:

“There are many forms of love and affection, some people can spend their whole lives together without knowing each other’s names. Naming is a difficult and time-consuming process; it concerns essences, and it means power. But on the wild nights who can call you home? Only the one who knows your name.”

She’s talking about understanding: the first step in being loved is to be truly seen, and understood. You can spend your whole life in a relationship and realize that you’ve never really been understood, that the person you’ve been with has never known your name. That’s a horrible realization to have . . .

But if you can find a person who does . . . Well then, it’s as though you are no longer on a planet spinning through space. It’s as though you’ve found, in this universe that is ceaselessly in motion, a place on which to stand. Solid ground . . .

January 27, 2013

Shadowlands

Recently, I’ve had three friends announce publicly that they’re going through depression. They are all women, all beautiful, all incredibly accomplished. The sorts of women that other people want to be, and want to be around.

When I was going through depression, I was public about it too. I’m not sure there’s any other way you can be, particularly when you have a public presence, as they all do. People begin to wonder what’s wrong with you, why you’re not tweeting, blogging, writing. Still, there’s such shame associated with it, with admitting that you are less than all right. That you can’t, in fact, deal. And people can make it worse in a variety of ways, by saying it will pass, you will be all right. That you should cheer up, shouldn’t be so sad. The worst is when they remind you of how lucky you are to have what you do have, when they tell you that you are so much better off than many other people. The implication is that if you have a best-selling book, or a major award, or significant publications, you really shouldn’t feel depressed. That your depression is a sort of ingratitude.

Which ends up making you feel depressed, ashamed, and ungrateful.

When you’re depressed, it’s impossible to ignore the criticism, because it’s an external form of your own internal dialog. When you’re depressed, nothing rolls off your back.

(Funnily enough, a blog post I wrote recently received a similar critical comment from a nameless reader — that I was unaware of my own privilege, and ungrateful for it. I left the comment up because it demonstrated, better than anything I could have written, my point that if you have a public presence of any sort, you will be criticized by people who don’t know you or where you’ve come from. But that criticism is much harder to take, almost impossible to take, when you’re depressed.)

My depression was connected to a specifically difficult time in my life, the two years in which I completed my doctoral dissertation. It took a while to go away, even after I graduated. And it changed me permanently. I’m stronger than I was before in some ways, but more fragile in others. I will never again have the easy toughness I once had. I miss it, sometimes. Nowadays, my sense of joy is more delicate. I am more aware that beneath the sunlit earth, there are Shadowlands. (I used to call depression “going to the Shadowlands.” Depression isn’t sadness. It’s blankness. It’s when reality loses one of its dimensions and becomes flat, monochromatic.) I can feel them there, and I can tell when stress or loneliness or tiredness, those things we all experience, brings me closer to them.

I’m not writing this blog post to say anything in particular, except that it makes me sad (not depressed, but sad) to see such wonderful friends, such creative, artistic spirits, going through that. When I heard them speak out about it, I thought, what is the appropriate response when someone tells you they are dealing with depression? Back when I talked about my own depression, there were a few people who gave me the only response that helped, which was “I’ve been there too.”

I thought that for this post, I would use one of the photographs I took at Stonecoast, of a stone wall.

It fits the mood of this post because it shows the cold monochrome of winter. But the truth is that when I took this picture, I was wonderfully, gratefully happy, because I was in an environment that was all about writing. I suppose that contradiction is appropriate . . .

January 26, 2013

Inner Countries

Do you have inner countries? I’ve always had them. I’ve always been able to go to other countries in my mind.

I remember the ways to reach them (because there is always a journey). Sometimes you have to climb over the mountain ridge before you see the valley. Sometimes you have to wait on the shore, until the boat shaped like a swan comes for you. It takes you to the island, and the castle. Sometimes all you have to do is step into the tapestry and find your way through the forest. (You will find your way, because you’ve been there before.)

I wonder if we are born imaginative, or become imaginative by circumstance? I think it’s a combination of both. It made a difference for me that I was a shy, dreamy child. When other children were playing kickball at recess, I was reading. My mind became populated by the things I was reading about, but there was also a consistency to my imagination, to the countries I had inside me. They were based on the fundamental premise that the world was alive, that animals and trees could communicate, that even rocks had things to say. That the true things were the old things: cottages made of stone, and ancient books — mountains, seas, and the great sky above. And that the world was filled with magic: shoes that took you wherever you wanted to go, mirrors that showed you whatever you wanted to see. I think J.R.R. Tolkien would say that my countries exist in Faerie, which he describes as the state in which magic can happen.

Of course, they still exist: I still have those countries inside me. Nowadays, I don’t visit as often as I used to. I have work to do, and there’s not as much time for dreaming as there used to be. But because I have them inside me, I’ve never accepted a simulacrum, a false country of the imagination. I don’t play video games. I barely watch television, and when I do, it’s because a show reminds me of the true countries of my imagination. They’re created by people who have true countries inside them as well, or so I believe. I would rather live in this world, and find in it places that remind me of those countries: I would rather have reality, and glimpse in it pieces of the countries I’ve known since a child. (I see pieces of them quite often: a stream running under a bridge, a horse standing in a field, a tangle of wild roses . . .) And since I am an adult, and a writer, I have the power to bring parts of those inner countries into this one — to write about them, or make them manifest in other ways.

I think that’s part of the writer’s, and more generally the artist’s, task. To bring his or her inner countries into reality, whether by showing where they exist in our world or describing and therefore creating them. Art changes our perceptions, which changes our reality (because our experience of reality is so fundamentally determined by our perceptions). The way an artist describes a copse of birches can change those birches for us.

When I see a copse of birches in winter, I can see the women sleeping inside them . . .

January 24, 2013

The Unsafe Life

I was struck, recently, by a contrast.

I have a friend named Joe. Except that Joe is not his real name. In fact, he doesn’t exist: Joe is a composite of various people I’ve know. But he’s a convenient example.

Joe’s a big guy, about twice my size. If you put him in a movie, he would be either the martial-arts expert hero or the martial-arts expert villain. He lives in a small town in the South, and he owns his own business. Let’s say he’s in construction. He builds things, makes things, some work that gives him a relatively steady and reliable source of income. He has a home, a family, a community. If he wanted, he could live exactly as he is living for the rest of his life.

How do I know Joe? I’m pretty sure we went to high school together. Or not, it doesn’t much matter. He’s just an example, remember.

What struck me recently, rather hard, is that of the two of us, I’m the one who lives an unsafe life. I don’t mean physically, although I live in a large city and regularly receive reports of local robberies from the university police. No, I mean in another way.

I’m the one who ended up going to law school, working as a corporate lawyer. There were days when I got on a plane in the morning, and got on another plane at night. I made telephone calls that moved millions of dollars around the world. It was a world in which the stakes were high, the responsibilities great. And I left that world for the even less safe one of being a writer and scholar. Less safe because after all, corporate law had been a path. If you followed the path, you would do well. But a writer and scholar has to create her own path. She is rewarded for her originality, her insight — her ability to say what has never been said before. To shed light.

I don’t think I ever expected to be where I am today: teaching at one of the largest research universities in the world, whose freshman class is larger than the entire population of Joe’s town, and in a well-known MFA program. Publishing steadily, being respected as a writer. But it’s difficult too: I am responsible for performing, for producing. Standing up in front of sixty students a day, showing them what they did not know before. Flying to conferences, speaking on panels, reading my stories. Delivering new stories, hopefully (but not always) by deadline. There is a point at which people ask you to do things not because you have the right training or skills (like a corporate lawyer), but because you’re you. Because they want a Theodora Goss story. Which is wonderful — but which also means being an artist, doing the work to become an artist, always questioning yourself. Always pushing yourself. Getting better, going deeper. And, of course, accepting criticism, because you’re out there. Presenting yourself to the world.

If I make it sound hard, that’s because it can be very hard. At least for someone like me, who is an introvert and would love to dream her life away, maybe reading books or planting a garden.

I have no idea what the future will bring. Sometimes I sit in my apartment in this great city at night, and feel afraid. And sometimes I envy Joe’s life. It seems so peaceful, one day essentially the same as another. He can grow a garden. He can read for fun. But I realize, looking at my own life, that I’ve always chosen the more difficult path, as though by instinct. The path of greater challenge, and greater freedom. I’ve always gotten on the plane and taken off, to wherever I’m going.

I’m not quite sure why. I think it has to do with the fact that I’m an artist. I think perhaps living an unsafe life is the only way to create art.

December 30, 2012

Going to Museums

Yesterday, Ophelia and I went to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The Gardener Museum was once the house of Isabella Stewart Gardner, a wealthy woman in the late nineteenth century. After the death of her husband, she turned to collecting; eventually, after her death, she left her house and collection as a museum, with the proviso that it not be altered. And it generally hasn’t been. The collection itself is interesting and idiosyncratic: it looks a bit as though she traveled through Europe picking up whatever struck her fancy, and what struck her fancy were often quite beautiful things. I told Ophelia that we were going to visit a castle, and the museum does rather look like a castle on the inside. This is the central courtyard:

I think I go to museums with Ophelia so often because I was taken to museums so often as a child. And not just museums: we were always going to ballets, operas, plays, concerts. (I was usually bored at the concerts.) Without thinking about it too much, my mother was steeping us in culture — I say without thinking about it too much because it was the way she herself had grown up. You did not necessarily have money — my family lost all its property after the war, and was only compensated for it after the fall of the communist regime — but you could always have culture. You could always know music and art. Where I grew up, in Washington D.C., most of the museums are free, so we would go in whenever we wanted, and often on weekends I would simply wander around the National Galleries or the Hirshhorn. Museums still feel like home to me: I feel perfectly at ease in them, as some people do in churches. I love to wander around and then sit in the café (there is always a café) with a cappuccino, reading or writing.

At the Gardner Museum, I took Ophelia to the café, which was terribly overpriced. But I suppose that’s part of the experience I’m giving her — I want her to feel comfortable in museums, and know how to behave in cafés and restaurants. (She’s eight, so I’m in the midst of that — trying to make sure she knows how to behave appropriately in public, knows the codes. Because living in society means knowing and negotiating a set of codes, doesn’t it? And I want her to know it, so that if she later wants to break the rules, she’ll know what they are and how to break them. You have to know a system if you want to rebel against it.) Today we are working on how to dress for an evening at the theater, because we’re going to Boston Ballet’s new Nutcracker at the Opera House. (I wanted to write this blog post before it was time for me to get dressed.)

I got something very special out of going to museums as a child, something I think most children don’t get. It seems to be reserved for an elite, although it shouldn’t be. (I was certainly not part of a social elite, as a child. Except perhaps educationally.) It’s the sense that human culture belongs to me, and I belong to it. That I participate in it. Picasso and Matisse are not intimidating. They are brothers in arms, and we are all trying to create something, to produce art of various sorts. Of course, some parts of that culture belong to me more than others, simply because of my own cultural heritage, and I would be wary of using material from non-European cultures. I would use it, but with more care. Nevertheless, there’s a sense, not so much of ownership, but of participation.

That matters to me deeply in my own art, and it’s something I want Ophelia to have as well.

December 27, 2012

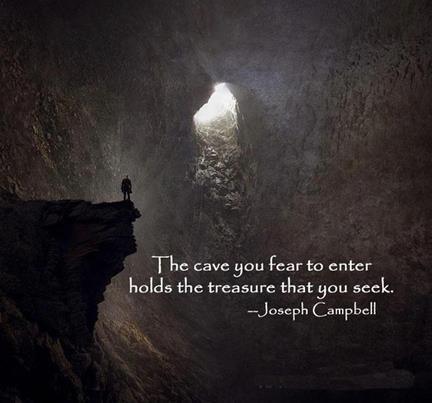

The Cave

On Facebook this week, I found the following quotation from Joseph Campbell:

Now, you should never trust a Facebook quotation, and of course I checked to see if Campbell had ever said this. He probably hadn’t, in exactly that form. What he may have said is something like this, in a lecture: “Where you stumble, there lies your treasure. The very cave you are afraid to enter turns out to be the source of what you are looking for. The damned thing in the cave, that was so dreaded, has become the center.”

So you’re afraid to enter the cave, you enter, you stumble in the darkness because the ground is rocky. But somewhere in that cave is the treasure, the thing you are looking for. To find it, you have to enter the cave in the first place.

I could write a blog post on overcoming fear and venturing into the cave. Except that’s not my problem. I always go into the cave. I’m not even sure why. I think I do it on principle, because I know that if you give in to fear once, you are more likely to give in to fear twice. You are more likely to hold back the next time, to say no, the cave is too dark, the ground too rocky. The things I’m afraid of are the same things I think we’re all afraid of. We often think of bravery as jumping out of airplanes, but seriously, who’s afraid of jumping out of an airplane? No, the things we’re afraid of are failure, loneliness, poverty. Being lost, facing rejection. Ultimately, death.

Being a writer means that you confront all of these. The path itself is a lonely one, and you face a continual possibility of rejection and failure. (You may remember that some time ago I wrote about how I deal with negative reviews? Everyone gets negative reviews. Well, to deal with mine, I read James Joyce’s negative reviews. I scroll through his one-star reviews on Goodreads. Seriously.) A book may be rejected by every publisher, a book may be published and fail. Poverty is a very real possibility. It’s easy to become lost. You can’t be a writer without going into the cave. I go into the cave so I can get used to being afraid. When I started going to conventions, I would always volunteer to moderate panels, in part so I would be put on panels, because there was always a need for moderators. You see, for some reason people are afraid to moderate. So I would find myself in front of two hundred people, moderating a panel that consisted of writers such as Samuel Delaney and Barry Malzberg and John Clute. When you do the things you fear, over and over again, you lose your fear of them. And you become used to the feeling of being afraid, so when you have to do the next thing you fear, you’re already accustomed to it. You know what it feels like. Eventually, you begin to want it, the feeling of being at least a little afraid, of moving past your comfort zone. You start to realize that if you’re not, to at least a certain extent, staring into the abyss, you’re not really living. You’re not even really writing.

So my problem isn’t going into the cave. My problem is that I always go into the cave, and then I stumble and fall. Not always of course, but sometimes. Then I feel stupid, and blame myself for having stumbled. For having failed to live up to expectations. That’s what I need to work on. Because I’ve met so many people who never even venture inside. People who tell me they have traveled the world, but when I ask them about it, reveal that all the trips were planned, were comfortable. People who call themselves romantics, but are afraid to fall in love — deeply, passionately in love with another person. Writers who are afraid to work on longer projects because of the fundamental fear that they will fail — that they will not finish, or the book will not find a publisher, or once published it will not sell.

What I need to do is pick myself up, mend anything that’s been broken, and say to myself, but I ventured into the cave. Of course I failed — that’s the sign of having tried. And then I need to look around for that treasure.

We should wear our failures as badges of honor, I think. Show off our scars, as soldiers used to show off the scars they gained in duels . . .

December 25, 2012

The Hellebore

I don’t usually write blog posts late at night. But tonight, I felt as though I had to. Earlier today, I had been scrolling through Facebook and had seen the image I’m including in this post: a picture of a hellebore. This post is a response to that image.

You see, hellebores are among my favorite flowers. I value them particularly because they bloom in winter, when all the other flowers are asleep, underground. They are a promise: that spring will come again, despite the darkness, despite the snow. Facebook is silly: you and I both know how silly it is. But sometimes it does allow you to see something magical, simply because it’s populated by human beings, who are intermittently magical. Some more than others, of course . . . Seeing this hellebore was like getting a glimpse of another country, like getting a sign that said “Wait, hope.”

Here, in case you are wondering what I’m talking about, is the image:

Tonight, I was trying to answer a question, which was, “Why do I feel so sick?” I thought, it’s the rich food — I never eat the way I’ve eaten in the last two days. (I had marzipan for breakfast.) I thought, it’s the lack of sleep — I’ve been overworked for so long now that I don’t remember how to be anything else. But no, I concluded. It’s something else, something deeper, a sickness not of the body but of the soul — and any sickness of the body is a symptom of that underlying sickness. I’ve gone too long needing something that is difficult to find — that deep connection with the world, or the world behind the world: the reality behind all our human games and constructs. I’ve gone too long saying and doing what I’m expected to, being who I’m expected to be. Moving through the world automatically, in a way I’ve learned to move through it, because don’t we all? So as to create the least possible friction.

Once upon a time, I lived in a teeny-tiny house in a forgotten town close to Boston, and I had a garden, in which I planted hellebores. They would come up every winter. I always dreamed that someday I would have a house with a large garden, one which bordered a wood, and in the wood I would plant all the wild flowers: hellebores, which are wild, and the old species daffodils, and fritillaries. I mention this because gardens can connect you to what is real, if they are real gardens, magical gardens. (Mine was magical.)

I’ve been so busy that I’ve barely been writing, and when I do write, it’s because someone has asked me for a story and offered me money for it. I barely write poetry anymore, because there’s no money in it. And yet I think poetry keeps us from becoming sick, and I think I’m healthiest when I can write poetry. It’s a sort of thermometer for the soul. (It occurred to me tonight that there is a certain irony in the fact that the world will pay me enough to live on for teaching others to write, but not for writing myself.)

The hellebore: it reminded me of all this, and helped me diagnose my own illness. But it cannot answer the question that remains, which is, what then? How to effect a cure? And that, I don’t know. But it does hold out the promise of spring after the snows . . .

December 22, 2012

The Black River

I went walking beside the river today. The river is a neighbor of mine, just out my back door and across a road. I visit it often, and what I’ve noticed is that it has its moods. Today the water was black and roiling. It was one of those cold, gray New England days, the day after the solstice, when it still feels as though light has drained from the world, even though you know, intellectually, that it’s coming back.

This is what the water looked like:

Looking down into that black water from the bridge above, I started thinking about our desire for the apocalyptic, our secret wish that the world would in fact end. We’ve seen this recently, haven’t we? I think we see it every few years. It seems to be a recurring aspect of human civilization: someone announces the apocalypse, and there is much rejoicing. Of course, the apocalypse never arrives. What we get instead is life going on, with its series of small apocalypses, intermittent acts of violence that seem to have no meaning. Instead of the end of the world, we get a shooting here or there. I suppose one attraction of the apocalypse is that it would provide us with meaning, with closure. That would be it, instead of this going on and on, this continuation of ordinary life.

I think at some level, I can understand why someone might be driven to acts of destruction. We call those acts senseless, but I’m not sure they are, and I suspect that part of my duty, as a writer, is to make sense of them. It’s not a pleasant duty: but I am a writer, and nothing human should be beyond me. Unfortunately, violence is all too human. To understand it, I have to understand what creates violent or destructive impulses in myself. Thinking about this, I immediately remembered Freud’s idea of the death drive, the desire for something that is not life, for a return to the inorganic. There are all sorts of ways in which I disagree with Freud, but I agree with him that we have that impulse, because I can feel it in myself. I am not afraid of heights. No, what I’m afraid of is jumping. It’s the part of myself that asks, what if I did? (I suspect many of us ask that question, and this is a case in which having a vivid imagination is a liability.) I can understand the desire for violence as a rupture of the ordinary, of daily continuity. I can understand how in certain circumstances, someone might want something, anything, to happen. A war, a bomb, a shooting. And I believe it’s important to understand, because only by understanding something can we present an alternative.

I believe that the opposite of violence is not peace, but art.

Art is a way to commit the extraordinary, to rupture ordinary life. To move us to a different plane of significance. It is the way to express most completely all that we are, including our will to life, our desire for death. A great work of art is an apocalypse, a bomb in the mind. It is at once an act of creation and destruction. I can’t walk through a room of Van Goghs without feeling that I am being remade, that parts of me are falling away, that I must change in response. When I write, it is as though I can jump into the dark water without actually jumping. Metaphor saves us . . .

Alice Walker wrote, “Writing saved me from the sin and inconvenience of violence.” That makes sense to me.

This is what the river looked like, when I pointed my camera not down into the water but across it. The buildings of the city glowed in the light of sunset. Day by day, this time of year reminds us, the light returns . . .

December 21, 2012

Keeping it Simple

Today was one of those days you spend running around, trying to do all the things that need to get done, and they’re all such small things, but they need to get done or there will be trouble and inconvenience to follow. For example, while I was in New York, one of the nose pieces on my glasses fell off: you know, those small pieces of plastic that keep the glasses on your nose. Of course, you can’t wear the glasses without them. So an important errand today was running to my optometrist’s and having the nose piece fixed. Such a small thing, and yet so necessary.

And I had to buy milk, because while I was gone the milk had gone sour, which means that I can’t make myself oatmeal for breakfast. And while I was out, I bought groceries just in general, including new flowers, because my flowers had mostly died. I’m not sure why, but in a fit of extravagance, I bought two bouquets, so I had plenty of flowers left over. Here is the main arrangement, on the table:

And here is the arrangement in the bathroom:

There are so many of those fiddly little things in our lives: glasses nose pieces, and cell phone batteries, and keys. Heels on shoes. They need to be fixed, or copied, or recharged, or glued on. Oh yes, and on my way home I had to pick up a new toaster, because I had spilled water on the counter and my toaster no longer worked. So I stopped in the hardware store and bought a new one.

I mention all this because life is full of such things, such errands. And if you want to live an interesting life, an artistic life, you have to minimize them. You can’t always be concerned with the fiddly things. I try to do that, conscientiously: to simplify. To have as few bills to pay as possible, to arrange my life so that I’m not endlessly taking care of things. So that the fundamental activities of life are simple. That’s partly why I’m so glad that I don’t have a car, which takes endless care. Last week, I packed my bag, got on the subway in Boston, got on a bus to New York, got on a subway in New York, and there I was: spending almost a week in New York, going to see and do fabulous things. This summer, although I’m not sure about this yet, I may well be doing the same thing, except in Europe. You would be astonished at how easy it is for me to pack, get on the subway, get on an airplane, get on the subway, and be in an apartment in Budapest. Or a house in London. Or anywhere.

That’s not to say that my life isn’t very full. Right now, it’s too full. I had a long meeting with a friend of mine in New York who is also in the publishing industry, and I told him that what I really needed right now were an agent, an accountant, and an assistant. And honestly, if I keep doing the sort of work I’m doing, steadily, those things will be necessary in the next year. But at least they’re part of my work. I try to simplify my life so that my work can be as complicated as it is.

And so that I can live fully, think and feel deeply. Create the complicated work I want to. That’s where I want the complication to be: on the page, in the story. So in life, I’m trying to keep it simple. Not that it always works, of course. But I do try. (My glasses are fixed, I have milk in the refrigerator, my toaster can even toast hot dog buns. And I have new flowers in my apartment. That means I’m good to go . . .)