Theodora Goss's Blog, page 24

October 14, 2013

What I’ve Learned

I had a birthday recently. And I thought about the things I’ve learned so far in life. There are a great many of them — after all, I have two graduate degrees, so I must have learned something. But I mean those fundamental lessons that you hold on to, that you use every day or week. And since it seems to be the fashion to make lists, I thought I would make a list of some things I’ve learned so far. This is, obviously, in no particular order — except the order in which I wrote them down.

1. You can tell the people who are strong, because they are also kind.

I’ve found this to be generally true, that people who are strong, who are confident and sure of themselves, certain about who they are and where they’re going, are also kind. They have no need to hurt others. The people who have hurt me have inevitably done so out of weakness, because they were uncertain about where they were going, unsure about who they were in the first place. Knowing that makes it easier to forgive people who hurt you. It’s also useful to know that when you are unkind, it’s usually because of some weakness in yourself.

2. It’s possible to live an extraordinary life, but it takes an enormous amount of work.

I know people who live extraordinary lives, who are creating great works of art, traveling all over the world. And they work very, very hard. Their example shows me that I, too, can have an extraordinary life. And to get working . . .

3. Almost all of your clothes can be washed in a machine or by hand. Except ballgowns: always get ballgowns professionally cleaned.

I suppose I should add business suits to that list, but I don’t have any business suits. That was one reason I left the law: I never wanted to wear a business suit again. And almost all of your clothes can be washed in hotel sinks, which is useful to know when you’re traveling all over the world, living that extraordinary life. (But jeans and socks take a very long time to dry.)

4. There will come a day when you realize that you’ve gotten everything you wanted, and then you will need to decide whether you wanted it after all, or were simply fulfilling the dreams that others or society had for you.

The earlier this day comes, the better, because it often involves a course correction. You may well decide that after all, the house in the suburbs and what was supposed to be a secure career make you feel like jumping in a lake. That you feel as though your soul is turning brown like one of your houseplants. It is better to change your life than jumping into a lake — harder, but better.

5. You must take care of your skin.

Cleanse, exfoliate, moisturize, apply sunscreen. As though you belonged to some obscure church of the skin, in which this ritual was considered necessary for the salvation of your immortal soul.

6. Clothing sizes bear absolutely no relation to the size of clothing.

The numbers on clothing bear no relation to anything on the material plane. They are a secret code used to communicate with spiritual beings in other dimensions, and are beyond our primitive understanding. Ignore them.

7. Everything you want to accomplish takes longer than you want it to take.

I’ve found that everything I’ve ever wanted, whether it’s going to graduate school, finishing my PhD, moving into the city, has taken me a year longer than I wanted it to take. When I desperately want to do something, and it isn’t getting done, I think — oh yes, the one year rule.

8. Learn how to be alone, or you will end up staying in relationships long past the time when you should have left.

I’ve seen so many people stay in relationships because they were afraid to be alone. Or get into relationships for that reason. It is much worse to be in a relationship that makes you feel alone than to actually be alone.

9. Your habits create who you are.

I hate to admit this, but it’s so true: what you do every day creates the person who are. At some point, I started exercising every day, and I started looking different. Like a person who exercises every day . . . When I write every day, I feel like a writer, I publish like a writer. When I don’t write every day, I feel lost. The small habits, the sleeping and eating and exercising and working, even what you wear every day, create who you are as a person. We like to think that we are who we are, and our habits come out of that — but we create who we are incrementally, out of all our habits. Day by day by day. (Which means we can also change ourselves, incrementally.)

10. You can buy happiness, but it’s called something else.

You can’t actually buy happiness, but you can in fact buy something that makes you happy. The trick is, that thing has to make you more the person you want to be. That’s what makes you happy, not the thing itself. Some time ago, I bought an adorable pair of pixie boots at Goodwill. They were $10 (the price is still on the bottom of the boot, in silver marker). They would not have made me happy if they had been too expensive, because that would have gone against my idea of myself — as someone who does not spend a great deal of money on clothes, but is nevertheless more chic than many people who do. Every time I wear those boots, I feel as though I’m dancing along the streets, as though I’m some sort of urban princess. They make me happy, because they allow me to be the person I want to be. Another thing that makes me happy? Buying plane tickets. So you can in fact buy happiness, but it’s called “pixie boots” or “plane tickets” or “dark chocolate.” If you’re unhappy, buying a little bit of happiness is not such as bad idea.

Here, by the way, are those boots, with a gray lace skirt and black jacket I wore to the theater this week. “Theater tickets”: that’s another way to buy happiness.

I’m sure there are things I could add to that list? I have, after all, learned more than ten things so far . . . But I’ll have to think about what they are. I thought I would end this blog post with a picture of me by the river, being pensive. And perhaps a little wiser than last year.

September 22, 2013

Alone Time

I’m so tired!

I’ve been meaning to keep up with this blog, to write three times a week, but there’s so much else to keep up with. So much taking energy . . .

It’s not the work, although I have a lot of that. But it’s manageable. What tires me out is the people — don’t get me wrong, I love people. And I have the good fortune to work with absolutely wonderful people — smart, dedicated students and supportive colleagues who are continually innovating in their work. I love everything I do . . .

My problem is that I’m an introvert, and hypersensitive (meaning that I over-respond to stimuli, like bright lights or medicine), and even a bit sensory defensive. So although I love people, I need alone time, when I can sit in a room, with the light dimmed, and do something like listen to soft music. All by myself.

I know I’m not the only one. Since I have so many friends who are writers and artists, many of my friends need alone time as well. They tend to be introverts, people who want to go deeply in life rather than broadly. And deeply often means deeply into themselves, which you can only do when you’re alone. The challenge of being an introvert, of drawing your energy from alone time and expending it during time with other people, is that you can go too much into yourself, spend too much time alone. I have to make sure I get out and socialize, not just see people during work.

(I have sixty students. So almost every day of the week, I’m with people. And I live in a large city, where when I step out the door I see people. Although sometimes being in a large city, where you don’t actually know the people you see on the street, can be refreshing, and not so different from alone time. There’s something lovely about anonymous time as well . . .)

In addition to spending this week with people, I’ve been sick, with always lowers my threshold for sensory stimuli. Some days, all I wanted to do was stay in bed . . .

So the trick is, trying to figure out how to get enough alone time in my days so that I can function well, because if I don’t get that alone time, I find that I’m tired and cranky. And you can’t really be cranky when you’re teaching. One thing that helps is going down to the river, who is a very restful sort of neighbor. (The river is almost out my back door, separated from me by a bridge. When I walk over the bridge, I’m right there, on the riverbank.)

I thought with this post I would include some photos of my favorite willow tree, whom I like to visit when I walk by the river. Here it is!

And here is me trying to be a willow spirit. Sometimes I just go and sit by the willow. I look at the river — I think looking at water is a good way to still and refresh the mind. We live metaphorically, although we often don’t realize it. Water is a metaphor for the unconscious, for the depths of the mind itself, and so looking at water can help you get there, to that still, deep part. And it can be cleansing, as water is. This was me after a long day of teaching, down by the willow . . .

(I feel as though I should write about this? Life as metaphor. When I have a little more time . . .)

September 12, 2013

The Little Things

I would make a terrible Buddhist.

I’m no good at non-attachment, and I’m not sure I would want to be. I get attached to all sorts of things, places and people and even teacups, and I get very sad when I have to leave, or I lose a friendship, or a teacup breaks. I should, of course, be philosophical and tell myself that all things pass away, but I can’t. I would rather feel the pain of loss and disappointment than be safe from it, in my own sensible, philosophical calm.

I’m too in love with the physical world, with the texture and experience of it: city streets, and tree bark, and oatmeal in the mornings with orange juice and a chai latte, and a vase of flowers to greet me, and twilight. Oscar Wilde once gave some very good advice, through the mouth of Lord Henry Wotton I think: “Nothing can cure the soul but the senses, just as nothing can cure the senses but the soul.” I look on this as accurate medical advice, at least for problems of the soul. (I haven’t had problems of the senses — they have all been problems of the soul, soul aches. Some of us are prone to them, I think.) So when I have an ache of the soul, I go on a walk and look at the river, or have a bowl of brownies and ice cream (together), or take a bubble bath. I go to the senses.

The little things can save you. Flowers in a vase, a doily on a wooden table, a painting on a wall. A book of fairy tales. Walking by a garden, or beneath a tree.

I can’t become unattached from the world, because the world is so splendid, heart-breakingly so. And that means my heart will indeed break, probably over and over again, but the cure for heartbreak, for aching of the soul, is the world itself in all its splendor. Particularly the little things: they tend to heal more than they hurt. A vase of flowers will probably not break your heart, but it will help ease heartbreak. They are the cures for the big things, the heart-breaking things. I don’t think you can have the healing without the heartbreak, the flowers without the hurt. Non-attachment means giving up desire, and therefore also escaping from suffering. But I don’t want to give up desire, even for a skirt that swirls around my ankles as I walk. Even for a soft blanket to curl up in, or a teacup with pink roses on it. Which means that I will suffer when the teacup breaks, or the skirt wears out. All things break, all things wear out eventually. We all die.

But I don’t think you get the splendor without the suffering. And I know that you can’t make art without the suffering. There is no necessary connection between art and suffering — but I think that to make art, you have to accept the ordinary conditions of being human. Saints, who have renounced the world, are the subjects of art rather than artists.

But my main point here isn’t about art or suffering. It’s about the little things, like flowers in a vase. Make sure you pay attention to the little things, for they will save you.

September 2, 2013

True Partnership

I’ve been thinking about relationships lately, partly because I have an idea for a book. Not the one I’m currently working on, which doesn’t focus on relationships — it focuses on friendships between women. But I mean romantic relationships, not friendships. We’ve had this idea, for the last hundred years or so, that we’re all supposed to be looking for True Love.

I say the last hundred years, because the idea of falling in love and then spending the rest of your life with the person you fell in love with is a fairly recent one. We trace romance back to the chivalric ideal, the Romances of the medieval period. But that was a very different ideal — there, your True Love was not the person you spent the rest of your life with. Romantic love happened outside the marital bond, and was destructive to it. Tristan and Isolde does not end with the marriage of Tristan and Isolde. It’s not until the eighteenth century, but even more so the nineteenth century, that we get people falling in love, getting married, and presumably living happily ever after — in a sense, the novel takes the plot of the fairy tale and moves it into the domestic sphere.

So we get the fairy tale idea of True Love, which we are all supposed to wish for, to try and find. I’m afraid I’ve gotten cynical about that lately. When you’re a writer, and interested in people, and good at listening, people tell you things — as though you were Hercules Poirot. And sometimes the relationships that look so lovely on the outside aren’t so lovely after all, when you hear about what happens on the inside. The thing is, someone can love you and still treat you horribly. Or at least, that’s what I’ve seen in some relationships. Tristan and Isolde weren’t so good to each other either.

So I have a different ideal than the cultural one, which is True Partnership. I see this too, and not infrequently. I suppose True Partnership includes True Love, but I think of it as a relationship in which love is not simply an emotion that the partners feel for one anther: it is instead a constant basis for action. Love is a verb, not just a noun. The people I know who seem to be True Partners (seem to be because of course we can never get inside a relationship) are each wholly themselves — they each have their own lives. But in addition, they also have a life together. That life allows them to develop as themselves, to keep their own identities. It does not operate as a constraint on who they are, and indeed it helps in their self-development. Each partner becomes more himself or herself in the relationship. Separated, they would each still be whole — but together, they are more than the sum of their parts. True Partnership involves both freedom and togetherness, both independence and trust.

I read an article recently about a couple who had done everything together, all their lives. At the end of their lives, they died within a week of one another. A lot of people though that was sweet — I thought it sounded like a play by Jean Paul Sartre. It would be claustrophobic, not to have one’s own life and identity, to be only a couple. And I’ve met people who hesitated to do what they wanted because the other partner would disapprove. Who quite literally needed to ask permission — whether to attend a social event or pursue their professional goals. I’ve never understood living like that.

The picture I’m going to include at the end of this blog post is of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. They seem, to me (and again, one can never get inside a relationship), an example of what True Partnership might look like. They weren’t interested in destroying each other, and would make for lousy opera. But they seem to have had a marriage that was truly good for them both.

(I suppose I’ve seen too many relationships in which people love each other, but at some level don’t actually like each other? They would love each other more if the other person could change, just a little . . . could become more of what they want in a mate. That’s a deadly sort of relationship. At least, I think it is, although I see it plenty.)

So, that’s my ideal: a True Partnership. Because I’m not sure that True Love is enough. I love opera, but who wants to end up in one?

August 31, 2013

Women and Trees

Recently, as I was scrolling down my Facebook newsfeed, I saw this picture:

It’s called “The Tree Spirit,” and it’s by an artist named Sean Andrew Murphy. It’s available as a print in his Etsy shop.

It made me think about women and trees. I’ve always loved trees, I think because they’re so solid. Trees are dependable: they may lose their leaves, but they’re still going to be there. The core of who they are will not change. When you are troubled, you could do much worse than going out and talking to a tree . . .

I’ve written several poems about women who fall in love with trees, and I think that’s because trees have qualities that we want in a partner. That solidity and dependability, the ability to keep growing, despite injuries. To grow around old hurts, to thrive despite them. A kind of perpetual renewal, yet also a permanence.

It makes sense that cultures other than our own have thought of trees as conscious, have painted or sung about men and women stepping out of trees. (When we aren’t looking, of course.) The Greeks had their dryads and hamadryads. When I was a child, I used to wonder what the man or woman of each tree would look like. I would try to imagine them, inspired I suppose by C.S. Lewis’ descriptions of the tree spirits in the Narnia books. For me, the most magical moment in the entire series is when Aslan brings the trees back to life, in Prince Caspian. The land has been asleep, under the rule of the Telmarines (who are early versions of muggles stuck in a land whose magic they disbelieve in on principle and reject out of fear). But when Aslan returns, it wakes up again — the magic is reborn. Looking at the world around me, I thought, we live in a land asleep. That must be why I can’t see the spirits of the trees and waters. That must be why magic doesn’t work. We’ve lost something, but if Aslan came . . .

Murphy says that his picture was inspired by Arthur Rackham, and sure enough Rackham has painted a woman and tree as well:

Now that I’m an adult, I keep reading news stories that reveal the strangeness of the world: elephants communicating at frequencies we don’t understand, trees creating communities underground with their roots. The world we see, the world we experience with our limited senses, is such a small part of the world that actually exists. It’s not as though we’ve lost the magic. It’s as though we willfully ignore it. We are the ones asleep — the rest of the world is still as awake as it ever was. This is where science and magic meet, and we find out that truth is more fantastical than our fantasies. Mother Nature is, after all, the greatest fantasy writer.

Before I thought of writing this blog post, I took a picture of me and posted it. I joked that I had decided to become a tree spirit.

It’s a bit of wishful thinking on my part — as though I could become a tree, become part of the natural world in a way I am not. Take on some of the qualities I admire in trees. I would like that . . .

The thing about this world is, Aslan isn’t coming. It’s up to all of us to wake up, and wake each other up.

The pictures by Murphy and Rackham both do that, because while they are literally false, they are figuratively and symbolically true. They express the deep truth of trees . . .

August 20, 2013

Loving Your Body

It’s a strange morning for me to be writing about loving your body, because I somehow managed to injure my shoulder again, so this morning I’m in pain. I first injured it when I was a lawyer, from too many late nights revising a set of contracts. They were two hundred pages long, and I spent months working on them as the transaction was being renegotiated: I was a junior associate, without the power to say wait, no, this work is injuring me. I ended up with a repetitive motion injury that is re-triggered when I work too hard, carry heavy bags on my shoulder (which I do all the time), spend too much time in front of the computer.

But I wanted to write about it, because it’s something I’ve been thinking about lately, and it seems like an important topic. It took me a ridiculously long time to learn to love my own body. I mean, I’ve been living in it all my life, most of the time not loving it at all. Not even liking it very much. And I suspect that’s where most of us live, feeling uncomfortable in our own skin most of the time. I’m not sure exactly what changed. I think it was a combination of things. I realized that I needed to take better care of it, partly because of old injuries, partly because I wanted to do all sorts of things in my life, and to do them I needed to be healthy. And once I started taking better care of it, my body became healthier, stronger. It began to feel more truly mine. Love is both a noun and a verb: it’s both the feeling of love and the act of loving. When you act in a loving way, you being to feel the emotion as well. So loving your body has a double meaning: both the feeling and the act. As important was the fact that I have a daughter who is growing up, and I want her to love her body. We teach by doing, not saying — if I wanted her to love her body, I had to model it in myself. I would be her primary example of what it meant to be a woman, and so I wanted to do it right, to the extent I could.

It’s strange that we generally don’t love our bodies, isn’t it? We’re so disconnected from them. I was thinking about why I ought to have loved my body all along, and I came up with three reasons.

1. It’s healthy. Both of my parents are doctors. I lived with my mother, who is a pediatrician. When I was a child, she worked at the National Institutes of Health. I still remember going with her to visit one of her patients, a girl my age who’d had multiple operations for cancer. She had a long scar down her abdomen. I grew up with the continual knowledge that the body could become ill, that illness was a part of human life. And then, when I was a teenager, my mother had cancer — she was younger than I am now. I have so many friends who are not healthy, who are dealing with medical situations of various sorts. I’m grateful simply for health. I rather hope that if my body weren’t healthy, I would still love it — but it’s ridiculous not to, when I can wake up in the morning, get out of bed, stretch, and know that I’m going to spend all day walking around, doing what I want to do. That, by itself, makes me grateful for the body I have.

2. It’s beautiful. I never realized how beautiful until I spent a week taking care of my grandmother, who was in her nineties at the time. She was bedridden, so she needed to be lifted, cared for the way an infant is. She was thin, frail — and I remember thinking that her body reminded me of a bird’s. For the first time, I was struck by the great beauty of the human body. The bodies we see in magazines, the bodies we are taught to call beautiful, never struck me as particularly beautiful, somehow. But I think I define beauty differently than most people — for me, beauty is complicated and contradictory. It has something in it of death. My grandmother’s body, in its final years, seemed to me worthy of being painted. An artist would have loved it. And in her body, I could see my own. I started to see the beauty in what we would probably call its imperfections.

3. It’s mine. It’s the only one I’m going to get, at least in this life. I spent most of my childhood wishing I could look like someone else. But I was never going to, was I? And no one else was going to look like me. So it was up to me to do my best with this particular body. To treat it as well as I could: give it good food, let it rest, make sure it exercises. Not work it too hard (which I tend to do). Because after all, it was me, the only me I would get unless we live more than one life (which I actually believe we do, in some form, in some way, although I don’t know how).

So there you have it. We have such problematic relationships with our own bodies, I’m not sure why. Perhaps because we grow up in a culture that tells us there are right and wrong ways to have bodies, be bodies. Perhaps because unlike other animals, we separate ourselves from our bodies. We often interact with the world as though we were brains being carried around by our bodies, rather than consciousness emanating from a physical structure. But the proper response to our bodies is always love. Even if we don’t like them at a particular moment, because you can’t change what you don’t love. There are things I need to change: I need to deal with this pain in my shoulder, for one. That means more yoga and less carrying heavy bags. But I’m glad that I’ve gotten to this point, where my body actually feels like me. And how strange that it took me so long to get here . . .

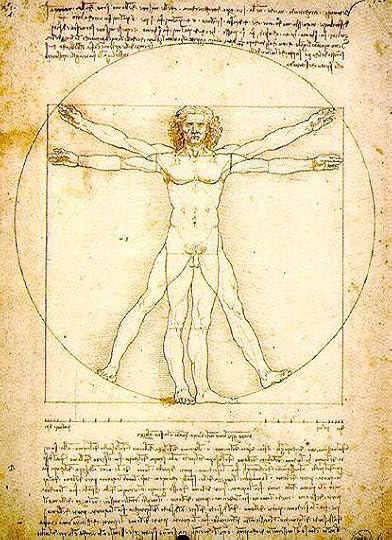

(I thought about what images to include with this blog post, and decided on some drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, who celebrates the human body so wonderfully, at all ages and in all different conditions.)

August 15, 2013

Craft and Art

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how grateful I am to be teaching creative writing. It’s different from teaching any other kind of writing. When I teach academic writing, for example, I teach students how to write in a certain way, how to make a persuasive argument in prose. I teach them how to introduce their argument, prove the argument in the paper, and then conclude by discussing the significance of what they have argued. When I teach creative writing, there’s no format, or not in the same way. The writer has to find the form of the story, and every story has a different form. Oh, there are formats I can teach, but they are useful to the writer only to the extent that they make the story more interesting, more compelling. The story, not the format, is of primary importance.

So I’ve been thinking about what I believe with respect to writing. Here are some of the things I believe:

I believe that there is a difference between craft and art. Craft is absolutely essential: to be an artist, you must know the craft of writing. You must understand how words mean, how sentences are put together, how to construct stories. When I teach writing, I teach craft. Art goes beyond craft, and has to do with what a writer, as an individual, brings to writing. Art is in the way Virginia Woolf explores consciousness. In the way George Orwell writes about politics. Both Woolf and Orwell make stylistic choices, write the way they write, because of what they’re focusing on, because of their convictions about reality. I can’t teach a student to write like Virginia Woolf. I can only teach a student why she wrote as she did.

What we think of as crafts can achieve the level of art, and what we think of as arts can be practiced as crafts. A quilt can become a work of art. And writing can be practiced purely as craft. I’ve read romances that are certainly good, as craft. And there’s nothing wrong with good craft. Not all writing has to aspire to art. But I teach my students to aspire, because I do believe that a work of art is a higher, more complex, more difficult thing to create. I can’t teach a student how to be an artist. I can teach good craft, and point the way toward great art. I can indicate what it looks like. (I think J.R.R. Tolkien was practicing a great art. His later imitators are examples of craft.)

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Stephen King subtitled his book on writing “A Memoir of the Craft” and E.M. Forster called his book The Art of the Novel. (These are two of my favorite books on writing.) King is primarily concerned with craft, as I think he should be. He was trying to teach, and craft is what can be taught. A writer is often better off simply focusing on the craft and letting the art take care of itself, at least for most of the writing process. Forster was concerned with how the novel, as a work of art, actually works.

I believe there is absolutely such a thing as talent, and that if we deny the existence of talent, we are kidding ourselves. I teach over a hundred students each year, and they come into my classes with different levels of ability. Some have a talent for writing, which means they can hear how words and sentences fit together, as a musician hears music. Writing is not necessarily any easier for them, but they approach it differently. However, a talent for writing should really be thought of as talents: in creative writing workshops, where all of my students are there because of their writing talent, I teach students who are good at poetic prose style, students who are good at plotting or creating compelling characters. Different students have different talents. And while talents are to a certain extent natural abilities, like the musician’s ear, all talents need to be developed. Talent is only the beginning, and talent can sometimes lead students astray. If they believe or rely too much on their natural abilities, they are liable to neglect the craft.

My role as a creative writing teacher is to take an individual with inclination, who has already demonstrated a basic level of talent, and work on the craft of writing. Which itself is a privilege. And then to point the way to art and say, if you wish, that’s where it is, in that general direction . . .

Woman Writing a Letter by Gerard Terborch

August 13, 2013

Fairy Tale Reading

This semester, I’ll be teaching a class on fairy tales. I thought you might like to know what I’m asking my students to read, because if you read this blog, you’re probably interested in fairy tales. Right?

So here’s my reading list:

The central text of the course is Maria Tatar’s The Classic Fairy Tales, from Norton. It contains most of the tales we’ll be reading, as well as important criticism. As we study each tale, the students will read Tatar’s introduction to that tale to provide historical and critical context. We will also be reading Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment, not because I necessarily agree with his psychoanalytic interpretations (I usually don’t) but because they give students a useful theoretical stance to argue for or against. The semester is arranged by fairy tales, so I’ll give you the stories and poems we’ll be reading by tale, mostly in the order we’ll be reading them.

We’ll start the semester with J.R.R. Tolkien’s “On Fairy Stories,” so we can consider the question “What is a fairy tale?” And then we’ll get into the tales themselves.

Little Red Riding Hood:

“The Story of Grandmother”

Charles Perrault, “Little Red Riding Hood”

Brothers Grimm, “Little Red Cap”

James Thurber, “The Little Girl and the Wolf”

Angela Carter, “In the Company of Wolves”

Snow White:

Brothers Grimm, “Snow White”

Anne Sexton, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”

Neil Gaiman, “Snow, Glass, Apples”

Cinderella:

Charles Perrault, “Donkeyskin”

Brothers Grimm, “Cinderella”

Anne Sexton, “Cinderella”

Aimee Bender, “The Color Master”

Beauty and the Beast:

Madame de Beaumont, “Beauty and the Beast”

Angela Carter, “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon”

Angela Carter, “The Tyger’s Bride”

Bluebeard:

Charles Perrault, “Bluebeard”

Joyce Carol Oates, “Blue-Bearded Lover”

Sylvia Townsend Warner, “Bluebeard’s Daughter”

Angela Carter, “The Bloody Chamber”

Margaret Atwood, “Bluebeard’s Egg”

Sleeping Beauty:

Charles Perrault, “Sleeping Beauty”

Brothers Grimm, “Briar Rose”

Ursula Le Guin, “The Poacher”

Jane Yolen, Briar Rose

We’ll finish the semester with a few classes on Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde. By Andersen, we’ll be reading “The Little Mermaid,” “The Shadow,” and “The Snow Queen.” By Wilde, we’ll be reading “The Selfish Giant” and “The Fisherman and His Soul.” To go with “The Snow Queen,” we’ll be reading Kelly Link’s “Travels with the Snow Queen.” We will also be reading two essays that touch on these stories: Jane Yolen’s “From Andersen On: Fairy Tales Tell Our Lives” and Ursula Le Guin’s “The Child and the Shadow.”

Throughout the semester, we will be reading critical articles, which I’ll list as well:

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, “Snow White and Her Wicked Stepmother”

Robert Darnton, “Peasants Tell Tales: The Meaning of Mother Goose”

Karen Rowe, “To Spin a Yarn: The Female Voice in Folklore and Fairy Tale”

Marina Warner, “The Old Wives’ Tale”

Zohar Shavit, “The Concept of Childhood and Children’s Folktales”

Jack Zipes, “Breaking the Disney Spell”

Maria Tatar, “Sex and Violence: The Hard Core of Fairy Tales”

Of course, the students will need to go out and find articles themselves, for their papers. I always find that the most useful for them to start with are those by Terri Windling, and anything linked to on the Sur La Lune website.

So there you go. That’s what we’ll be reading during the semester. I hope you go out and find some of the stories yourself — or even the essays and articles, if you’re interested in fairy tales! (And I think you are . . .)

August 12, 2013

The Poetry Collection

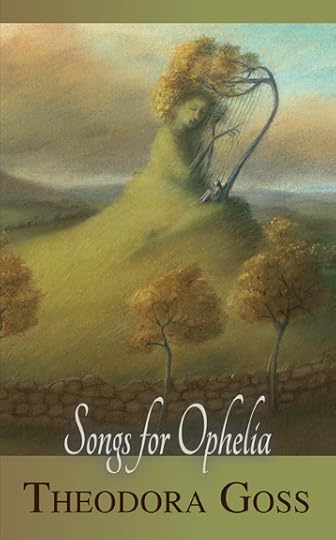

So, I have this poetry collection coming out?

You can hear the hesitation with which I write that. I trained myself, over many years, to take compliments well. When someone said “You look beautiful,” I learned to say “Thank you.” (I didn’t train myself to believe it, but I did train myself not to say something like, “Oh, but I looked dreadful this morning, you should see me when I first wake up.”) I think I need to train myself to talk about my poetry in the same way, so I can say “I have a poetry collection coming out” as though it were a normal thing, as though I didn’t worry about it terribly.

Why do I worry about it? Because I’ve never in my life had confidence in myself as a poet. No, wait, I did have confidence once, when I was in high school. Back then, I wrote poetry constantly and confidently. I published some of it in the school poetry magazine. It was college that created problems for me, specifically the poetry classes I took at the University of Virginia. UVA has a famous creative writing program, with famous poets teaching in it. And, I’m sure without intending it or perhaps even realizing it, they convinced me that what I wrote was not worth writing.

Here, by the way, is the poetry collection, and I can tell you that I’m very proud of it. It’s forthcoming from the wonderful Papaveria Press.

In my literature classes, we studied poetry from all eras. But in creative writing classes, we were expected to read modern poetry, and to appreciate modern poets specifically. A lot of what we were reading, I simply did not like, but I got the distinct sense that I was supposed to write that sort of thing. (I should say, here, that there is a great deal of modern poetry I love, if by modern we mean 20th century. But we were reading the poetry of the 1970s and 80s, and I had a difficult time getting excited about any of it. Contemporary poetry feels more spacious now than it did back then.)

The last poetry class I took was with a famousish poet, the kind of poet who gets into all the anthologies. My first poem was about a woman who has dragons moving into her house — small ones, that get “tangled in her hangers.” I remember those words from the poem. When we critiqued it, my classmates couldn’t understand what I was trying to do — why dragons? They were, of course, a metaphor — but I wasn’t treating them as a metaphor in an obvious way, just writing about what a pain it was to have dragons (small ones) in your house.

That class didn’t stop me from writing poetry. I kept writing and even publishing poetry, all through law school. (I published poetry before I published prose.) But I didn’t talk about it, as though poetry were some sort of disease it was best not to discuss too much. I was surprised when people liked my poems — it’s been a surprise to me, over the last few years, that they’ve been reprinted in Year’s Best anthologies, and that editors like Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow ask me for poems. The greatest surprise was when, with great trepidation, I posted some poems on Facebook and people told me how much they liked them — shared them with friends, commented.

And now I have this poetry collection coming out, so I’m determined to talk about it.

It’s not polite to write about poetry without including some, so here is a poem that should be appropriate for the season:

Autumn, the Fool

The leaves float on the water like patches of motley.

Autumn, the fool, has dropped them into the lake,

where they rival the costume, not of the staid brown duck,

but the splendid drake.

He capers down the lanes in his ragged garments,

a comical figure shedding last year’s leaves,

but as he passes the crickets begin their wailing

and the chipmunk grieves.

The willow bends down to watch herself in the water

and shivers at the sight of her yellow hair.

Autumn the fool has passed her, and soon her branches

will be bare.

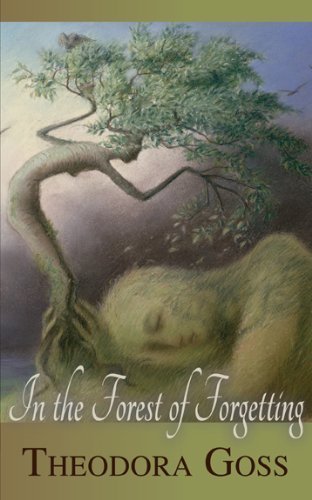

By the way, if you’re interested in the collection, it’s meant as a companion to my short story collection In the Forest of Forgetting, which is being reissued by Papaveria Press in a beautiful new edition:

It’s going to be available in paperback and is already available for the Kindle and in epub and mobi versions.

August 11, 2013

The Lady Code

In Victorian novels, there is one thing characters always seem to know: whether or not a woman is a lady. And whether or not she’s a lady determines how they talk to her, treat her. It’s as though there’s “lady code” that immediately signals her status. The code has to do with the tangible, such as clothing, but also the intangible, such as attitude.

I was thinking about this recently because I saw a photograph of a college student who had written on her leg, in black marker, what the different skirt lengths meant. A skirt that came to the middle of the thigh meant “flirty.” One just below the knee meant “proper.” One at the bottom of the calf meant “prudish.” And of course one close to the top of the thigh meant “whore.” There were gradations in between.

If we look at this idea historically, it’s the same old lady code. That code always had to do, in part, with sexuality. But it also had to do with social class, and what the photograph can’t represent, being a photograph, is the extent to which the lady code is about economic and educational status.

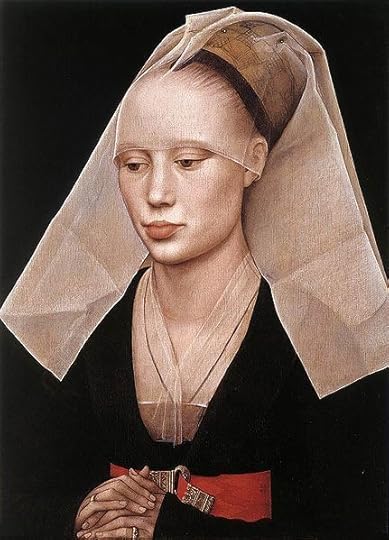

Portrait of a Lady by Rogier van der Weyden

In American, we are raised with an implicit lady code, because we tend not to talk about social status. But upper-middle class girls are educated into it: they are taught what to wear, usually by their mothers. They are taught which skirts are too short, which shirts too tight. They are taught to signal their social status in coded ways. My family is Eastern European, so the lady code was much more explicit. If I wore something inappropriate, my mother told me that I was not allowed to wear it because I would look like a prostitute. For me, raised as an American child, this was a shocking statement. Here, girls are explicitly taught to wear clothing that is sexually alluring: they are taught this by every magazine and television show. But they are implicitly judged by the lady code.

Portrait of a Lady by John Hoppner

So dressing, for a woman, is a complicated affair. When you look into your closet in the morning — and even before that, when you buy your clothes in a store or online — you are making a choice about what you want to communicate. You are speaking in a coded language. If you were raised by an upper-middle-class mother, you know the lady code. You are fluent in that particular language. You know that what you wear should vary depending on the occasion. You will not wear a cocktail dress to the ballet. (I use that as an example because it’s one I see whenever I go to the ballet: women wearing dresses that signal “I don’t go to the ballet often.” The lady code is nuanced: one kind of black dress is fine for the ballet, another kind of black dress is not.) You will not wear a suit that is either flirty or prudish to a job interview: a skirt that is too long is as wrong as a skirt that is too short.

Nicole Kidman in Portrait of a Lady

Perhaps the place I saw the lady code operating most clearly was at law firms, when I was a lawyer. There was a clear, although implicit and coded, distinction between female lawyers and female secretaries. They wore different clothes, different jewelry, did their hair and makeup differently. We did not have many male secretaries in those days, so male lawyers did not need to signal their difference so clearly. What they wore was relatively simple: a suit. For women, it was not simple at all, and I still remember endless discussions about whether or not a pants suit would be appropriate, and in what circumstances. I don’t think I wore pants once, as a corporate lawyer.

I write this not to make a statement about it, because I don’t know what statement I would make: the lady code has been with us since at least the Middle Ages, and I suspect that reading each others’ clothing as though it were a language goes back to when we first started wearing clothes. Should we abolish the lady code? I doubt we can. Should we be conscious of it? Yes, probably. We have an example of absolute mastery of that code in our First Lady. Michelle Obama’s clothing choices are brilliant: always perfectly appropriate, but also implicitly referring back to one of our great national examples of a lady, Jacqueline Kennedy. Her clothes are a form of political speech that invite us to compare her husband’s administration to Camelot. There is a whole other blog post to be written about the lady code and race, but it should be written by someone who knows the situation from the inside.

What I want to do here is simply notice that the code exists, despite the fact that mothers no longer tell their daughters to be ladylike. Instead, they are taught to be “appropriate,” which means pretty much the same thing. And to notice the ways in which the code is about, and signals, social and educational status. Which is important, because what a woman signals in that code will determine how she is treated and thought of in our society — just as it did for the Victorians.