Theodora Goss's Blog, page 23

December 26, 2013

VI. The Spinning Wheel

This is the fifth section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

It has never wanted to be an assassin. It remembers the cottage on the Isles where it was first made: the warmth of the hearth and the feel of its maker’s hands, worn smooth from rubbing and lanolin.

It remembers the first words it heard: “And why are you carving roses on it, then?”

“This one’s for a lady. Look how slender it is. It won’t take your upland ram’s wool. Yearling it’ll have to be, for this one.”

At night it heard the waves crashing on the rocks, and it listened as their sound mingled with the snoring of its maker and his wife. By day it heard the crying of the sea birds. But it remembered, as in a dream, the songs of inland birds and sunlight on a stone wall. Then the fishermen would come, and one would say, “What’s that you’re making there, Enoch? Is it for a midget, then?”

Its maker would stroke it with the tips of his fingers and answer, “Silent, lads. This one’s for a lady. It’ll spin yarn so fine that a shawl of it will slip through a wedding ring.”

It has never wanted to be an assassin, and as it sits in a cottage to the south, listening as Madeleine mutters to herself, it remembers the sounds of seabirds and tries to forget that it was made, not to spin yarn so fine that a shawl of it will slip through a wedding ring, but to kill the King’s daughter.

(Illustration by Edmund Dulac.)

December 25, 2013

V. The Queen Dowager

This is the fifth section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

What is the girl doing? Playing at tug-of-war, evidently, and far too close to the stream. She’ll tear her dress on the rosebushes. Careless, these young people, thinks the Queen Dowager. And who is she playing with? Young Lord Harry, who will one day be Count of Edinburgh. The Queen Dowager is proud of her keen eyesight and will not wear spectacles, although she is almost sixty-three.

What a pity the girl is so plain. The Queen Dowager jabs her needle into a black velvet slipper. Eyes like boiled gooseberries that always seem to be staring at you, and no discipline. Now in her day, thinks the Queen Dowager, remembering backboards and nuns who rapped your fingers with canes, in her day girls had discipline. Just look at the Queen: no discipline. Two miscarriages in ten years, and dead before her thirtieth birthday. Of course linen is so much cheaper now that the kingdoms are united. But if only her Jims (which is how she thinks of the King) could have married that nice German princess.

She jabs the needle again, pulls it out, jabs, knots. She holds up the slipper and then its pair, comparing the roses embroidered on each toe in stitches so even they seem to have been made by a machine. Quite perfect for her Jims, to keep his feet warm on the drafty palace floors.

A tearing sound, and a splash. The girl, of course, as the Queen Dowager could have warned you. Just look at her, with her skirt ripped up one side and her petticoat muddy to the knees.

“I do apologize, Madam. I assure you it’s entirely my fault,” says Lord Harry, bowing with the superfluous grace of a dancing master.

“It is all your fault,” says the girl, trying to kick him.

“Alice!” says the Queen Dowager. Imagine the Queen wanting to name the girl Elaine. What a name, for a Princess of Britannia.

“But he took my book of poems and said he was going to throw it into the stream!”

“I’m perfectly sure he did no such thing. Go to your room at once. This is the sort of behavior I would expect from a chimney sweep.”

“Then tell him to give my book back!”

Lord Harry bows again and holds out the battered volume. “It was always yours for the asking, your Highness.”

Alice turns away, and you see what the Queen Dowager cannot, despite her keen vision: Alice’s eyes, slightly prominent, with irises that are indeed the color of gooseberries, have turned red at the corners, and her nose has begun to drip.

(Illustration by Margaret Tarrant.)

December 24, 2013

IV. The King

This is the fourth section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

What would you do, if you were James IV of Britannia, pacing across your council chamber floor before your councilors: the Count of Edinburgh, whose estates are larger than yours and include hillsides of uncut wood for which the French Emperor, who needs to refurbish his navy after the disastrous Indian campaign, would pay handsomely; the Earl of York, who can trace descent, albeit in the female line, from the Tudors; and the Archbishop, who has preached against marital infidelity in his cathedral at Aberdeen? The banner over your head, embroidered with the twelve-petaled rose of Britannia, reminds you that your claim to the throne rests tenuously on a former James’ dalliance. Edinburgh’s thinning hair, York’s hanging jowl, the seams, edged with gold thread, where the Archbishop’s robe has been let out, warn you, young as you are, with a beard that shines like a tangle of golden wires in the afternoon light, of your gouty future.

Britannia’s economy depends on the wool trade, and spun wool sells for twice as much as unspun. Your income depends on the wool tax. The Queen, whom you seldom think of as Elizabeth, is young. You calculate: three months before she recovers from the birth, nine months before she can deliver another child. You might have an heir by next autumn.

“Well?” Edinburgh leans back in his chair, and you wish you could strangle his wrinkled neck.

You say, “I see no reason to destroy a thousand spinning wheels for one madwoman.” Madeleine, her face puffed with sleep, her neck covered with a line of red spots where she lay on the pearl necklace you gave her the night before, one black hair tickling your ear. Clever of her, to choose a spinning wheel. “I rely entirely on Wolfgang Magus,” whom you believe is a fraud. “Gentlemen, your fairy tales will have taught you that magic must be met with magic. One cannot fight a spell by altering material conditions.”

Guffaws from the Archbishop, who is amused to think that he once read fairy tales.

You are a selfish man, James IV, and this is essentially your fault, but you have spoken the truth. Which, I suppose, is why you are the King.

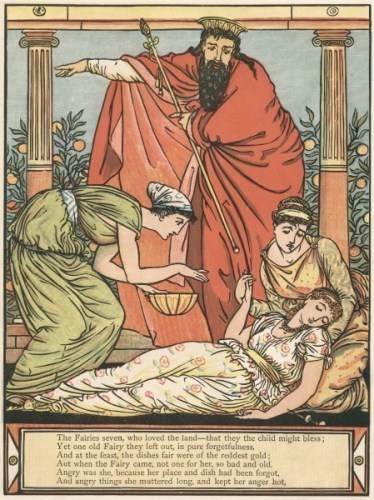

(Illustration by Walter Crane.)

IV. THE KING

This is the fourth section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

What would you do, if you were James IV of Britannia, pacing across your council chamber floor before your councilors: the Count of Edinburgh, whose estates are larger than yours and include hillsides of uncut wood for which the French Emperor, who needs to refurbish his navy after the disastrous Indian campaign, would pay handsomely; the Earl of York, who can trace descent, albeit in the female line, from the Tudors; and the Archbishop, who has preached against marital infidelity in his cathedral at Aberdeen? The banner over your head, embroidered with the twelve-petaled rose of Britannia, reminds you that your claim to the throne rests tenuously on a former James’ dalliance. Edinburgh’s thinning hair, York’s hanging jowl, the seams, edged with gold thread, where the Archbishop’s robe has been let out, warn you, young as you are, with a beard that shines like a tangle of golden wires in the afternoon light, of your gouty future.

Britannia’s economy depends on the wool trade, and spun wool sells for twice as much as unspun. Your income depends on the wool tax. The Queen, whom you seldom think of as Elizabeth, is young. You calculate: three months before she recovers from the birth, nine months before she can deliver another child. You might have an heir by next autumn.

“Well?” Edinburgh leans back in his chair, and you wish you could strangle his wrinkled neck.

You say, “I see no reason to destroy a thousand spinning wheels for one madwoman.” Madeleine, her face puffed with sleep, her neck covered with a line of red spots where she lay on the pearl necklace you gave her the night before, one black hair tickling your ear. Clever of her, to choose a spinning wheel. “I rely entirely on Wolfgang Magus,” whom you believe is a fraud. “Gentlemen, your fairy tales will have taught you that magic must be met with magic. One cannot fight a spell by altering material conditions.”

Guffaws from the Archbishop, who is amused to think that he once read fairy tales.

You are a selfish man, James IV, and this is essentially your fault, but you have spoken the truth. Which, I suppose, is why you are the King.

(Illustration by Walter Crane.)

December 23, 2013

III. The Magician

This is the third section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the previous sections, look below!

Wolfgang Magus places the rose he picked that morning in his buttonhole and looks at his reflection in the glass. He frowns, as his master Herr Doktor Ambrosius would have frowned, at the scarecrow in faded wool with a drooping gray mustache. A sad figure for a court magician.

“Gott in Himmel,” he says to himself, a childhood habit he has kept from nostalgia, for Wolfgang Magus is a reluctant atheist. He knows it is not God’s fault but the King’s, who pays him so little.

If the King were to pay him, say, another shilling per week — but no, that too he would send to his sister, dying of consumption at a spa in Berne. His mind turns, painfully, from the memory of her face, white and drained, which already haunts him like a ghost.

He picks up a volume of Goethe’s poems that he has carefully tied with a bit of pink ribbon and sighs. What sort of present is this, for the Princess’ christening?

He enters the chapel with shy, stooping movements. It is full, and noisy with court gossip. As he proceeds up the aisle, he is swept by a Duchess’ train of peau de soie, poked by a Viscountess’ aigrette. The sword of a Marquis smelling of Napoleon-water tangles in his legs, and he almost falls on a Baroness, who stares at him through her lorgnette. He sidles through the crush until he comes to a corner of the chapel wall, where he takes refuge.

The christening has begun, he supposes, for he can hear the Archbishop droning in bad Latin, although he can see nothing from his corner but taxidermed birds and heads slick with macassar oil. Ah, if the Archbishop could have learned from Herr Doktor Ambrosius! His mind wanders, as it often does, to a house in Berlin and a laboratory smelling of strong soap, filled with braziers and alembics, books whose covers have been half-eaten by moths, a stuffed basilisk. He remembers his bed in the attic, and his sister, who worked as the Herr Doktor’s housemaid so he could learn to be a magician. He sees her face on her pillow at the spa in Berne and thinks of her expensive medications.

What has he missed? The crowd is moving forward, and presents are being given: a rocking horse with a red leather saddle, a silver tumbler, a cap embroidered by the nuns of Iona. He hides the volume of Goethe behind his back.

Suddenly, he sees a face he recognizes. One day she came and sat beside him in the garden, and asked him about his sister. Her brother had died, he remembers, not long before, and as he described his loneliness, her eyes glazed over with tears. Even he, who understands little about court politics, knew she was the King’s mistress.

She disappears behind the scented Marquis, then appears again, close to the altar where the Queen, awkwardly holding a linen bundle, is receiving the Princess’ presents. The King has seen her, and frowns through his golden beard. Wolfgang Magus, who knows nothing about the feelings of a king toward his former mistress, wonders why he is angry.

She lifts her hand in a gesture that reminds him of the Archbishop. What fragrance is this, so sweet, so dark, that makes the brain clear, that makes the nostrils water? He instinctively tabulates: orris-root, oak gall, rose petal, dung of bat with a hint of vinegar.

Conversations hush, until even the Baronets, clustered in a rustic clump at the back of the chapel, are silent.

She speaks: “This is the gift I give the Princess. On her seventeenth birthday she will prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and die.”

Needless to describe the confusion that follows. Wolfgang Magus watches from its edge, chewing his mustache, worried, unhappy. How her eyes glazed, that day in the garden. Someone treads on his toes.

Then, unexpectedly, he is summoned. “Where is that blasted magician!” Gloved hands push him forward. He stands before the King, whose face has turned unattractively red. The Queen has fainted and a bottle of salts is waved under her nose. The Archbishop is holding the Princess, like a sack of barley he has accidentally caught.

“Is this magic, Magus, or just some bloody trick?”

Wolfgang Magus rubs his hands together. He has not stuttered since he was a child, but he answers, “Y–yes, your Majesty. Magic.” Sweet, dark, utterly magic. He can smell its power.

“Then get rid of it. Un-magic it. Do whatever you bloody well have to. Make it not be!”

Wolfgang Magus already knows that he will not be able to do so, but he says, without realizing that he is chewing his mustache in front of the King, “O–of course, your Majesty.”

(Illustration by Edmund Dulac.)

December 22, 2013

II. The Queen

This is the second section of my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals.” If you would like to see the first section, “The Witch,” look below!

Petals fall from the roses that hang over the stream, Empress Josephine and Gloire de Dijon, which dislike growing so close to the water. This corner of the garden has been planted to resemble a country landscape in miniature: artificial stream with ornamental fish, a pear tree that has never yet bloomed, bluebells that the gardener plants out every spring. This is the Queen’s favorite part of the garden, although the roses dislike her as well, with her romantically diaphanous gowns, her lisping voice, her poetry.

Here she comes, reciting Tennyson.

She holds her arms out, allowing her sleeves to drift on the slight breeze, imagining she is Elaine the lovable, floating on a river down to Camelot. Hard, being a lily maid now her belly is swelling.

She remembers her belly reluctantly, not wanting to touch it, unwilling to acknowledge that it exists. Elaine the lily maid had no belly, surely, she thinks, forgetting that Galahad must have been born somehow. (Perhaps he rose out of the lake?) She imagines her belly as a sort of cavern, where something is growing in the darkness, something that is not hers, alien and unwelcome.

Only twelve months ago (fourteen, actually, but she is bad at numbers), she was Princess Elizabeth of Hibernia, dressed in pink satin, gossiping about the riding master with her friends, dancing with her brothers through the ruined arches of Westminster Cathedral, and eating too much cake at her seventeenth birthday party. Now, and she does not want to think about this so it remains at the edges of her mind, where unpleasant things, frogs and slugs, reside, she is a cavern with something growing inside her, something repugnant, something that is not hers, not the lily maid of Astolat’s.

She reaches for a rose, an overblown Gloire de Dijon that, in a fit of temper, pierces her finger with its thorns. She cries out, sucks the blood from her finger, and flops down on the bank like a miserable child. The hem of her diaphanous dress begins to absorb the mud at the edge of the water.

(Illustration by Margaret Tarrant.)

December 21, 2013

I. The Witch

So, I decided to do something this holiday season? Which is: I decided to post my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals,” which was my first published story, and doesn’t appear anywhere online. It’s my holiday gift to anyone who happens to want a story this season. It’s based on “Sleeping Beauty,” so it’s a fairy tale of sorts. The story was written in twelve sections, one for each of the characters. Here is the first one, “The Witch.” The other characters will be appearing day by day, so if you’re interested in reading more, check back here daily . . .

This rose has twelve petals. Let the first one fall: Madeleine taps the glass bottle, and out tumbles a bit of pink silk that clinks on the table—a chip of tinted glass—no, look closer, a crystallized rose petal. She lifts it into a saucer and crushes it with the back of a spoon until it is reduced to lumpy powder and a puff of fragrance.

She looks at the book again. “Petal of one rose crushed, dung of small bat soaked in vinegar.” Not enough light comes through the cottage’s small-paned windows, and besides she is growing nearsighted, although she is only thirty-two. She leans closer to the page. He should have given her spectacles rather than pearls. She wrinkles her forehead to focus her eyes, which makes her look prematurely old, as in a few years she no doubt will be. Bat dung has a dank, uncomfortable smell, like earth in caves that has never seen sunlight.

Can she trust it, this book? Two pounds ten shillings it cost her, including postage. She remembers the notice in The Gentlewoman’s Companion: “Every lady her own magician. Confound your enemies, astonish your friends! As simple as a cookery manual.” It looks magical enough, with Compendium Magicarum stamped on its spine and gilt pentagrams on its red leather cover. But the back pages advertise “a most miraculous lotion, that will make any lady’s skin as smooth as an infant’s bottom” and the collected works of Scott.

Not easy to spare ten shillings, not to mention two pounds, now that the King has cut off her income. Rather lucky, this cottage coming so cheap, although it has no proper plumbing, just a privy out back among the honeysuckle.

Madeleine crumbles a pair of dragonfly wings into the bowl, which is already half full: orris root; cat’s bones found on the village dust heap; oak gall from a branch fallen into a fairy ring; madder, presumably for its color; crushed rose petal; bat dung.

And the magical words, are they quite correct? She knows a little Latin, learned from her brother. After her mother’s death, when her father began spending days in his bedroom with a bottle of beer, she tended the shop, selling flour and printed cloth to the village women, scythes and tobacco to the men, sweets to children on their way to school. When her brother came home, he would sit at the counter beside her, saying his amo, amas. The silver cross he earned by taking a Hibernian bayonet in the throat is the only necklace she now wears.

She binds the mixture with water from a hollow stone and her own saliva. Not pleasant this, she was brought up not to spit, but she imagines she is spitting into the King’s face, that first time when he came into the shop, and leaned on the counter, and smiled through his golden beard. “If I had known there was such a pretty shopkeeper in this village, I would have done my own shopping long ago.”

She remembers: buttocks covered with golden hair among folds of white linen, like twin halves of a peach on a napkin. “Come here, Madeleine.” The sounds of the palace, horses clopping, pageboys shouting to one another in the early morning air. “You’ll never want for anything, haven’t I told you that?” A string of pearls, each as large as her smallest fingernail, with a clasp of gold filigree. “Like it? That’s Hibernian work, taken in the siege of London.” Only later does she notice that between two pearls, the knotted silk is stained with blood.

She leaves the mixture under cheesecloth, to dry overnight.

Madeleine walks into the other room, the only other room of the cottage, and sits at the table that serves as her writing desk. She picks up a tin of throat lozenges. How it rattles. She knows, without opening it, that there are five pearls left, and that after next month’s rent there will only be four.

Confound your enemies, she thinks, peering through the inadequate light, and the wrinkles on her forehead make her look prematurely old, as in a few years she certainly will be.

(The painting is Sleeping Beauty by Sir Edward Burne Jones.)

The Witch

So, I decided to do something this holiday season? Which is: I decided to post my story “The Rose in Twelve Petals,” which was my first published story, and doesn’t appear anywhere online. It’s my holiday gift to anyone who happens to want a story this season. It’s based on “Sleeping Beauty,” so it’s a fairy tale of sorts. The story was written in twelve sections, one for each of the characters. Here is the first one, “The Witch.” The other characters will be appearing day by day, so if you’re interested in reading more, check back here daily . . .

This rose has twelve petals. Let the first one fall: Madeleine taps the glass bottle, and out tumbles a bit of pink silk that clinks on the table—a chip of tinted glass—no, look closer, a crystallized rose petal. She lifts it into a saucer and crushes it with the back of a spoon until it is reduced to lumpy powder and a puff of fragrance.

She looks at the book again. “Petal of one rose crushed, dung of small bat soaked in vinegar.” Not enough light comes through the cottage’s small-paned windows, and besides she is growing nearsighted, although she is only thirty-two. She leans closer to the page. He should have given her spectacles rather than pearls. She wrinkles her forehead to focus her eyes, which makes her look prematurely old, as in a few years she no doubt will be. Bat dung has a dank, uncomfortable smell, like earth in caves that has never seen sunlight.

Can she trust it, this book? Two pounds ten shillings it cost her, including postage. She remembers the notice in The Gentlewoman’s Companion: “Every lady her own magician. Confound your enemies, astonish your friends! As simple as a cookery manual.” It looks magical enough, with Compendium Magicarum stamped on its spine and gilt pentagrams on its red leather cover. But the back pages advertise “a most miraculous lotion, that will make any lady’s skin as smooth as an infant’s bottom” and the collected works of Scott.

Not easy to spare ten shillings, not to mention two pounds, now that the King has cut off her income. Rather lucky, this cottage coming so cheap, although it has no proper plumbing, just a privy out back among the honeysuckle.

Madeleine crumbles a pair of dragonfly wings into the bowl, which is already half full: orris root; cat’s bones found on the village dust heap; oak gall from a branch fallen into a fairy ring; madder, presumably for its color; crushed rose petal; bat dung.

And the magical words, are they quite correct? She knows a little Latin, learned from her brother. After her mother’s death, when her father began spending days in his bedroom with a bottle of beer, she tended the shop, selling flour and printed cloth to the village women, scythes and tobacco to the men, sweets to children on their way to school. When her brother came home, he would sit at the counter beside her, saying his amo, amas. The silver cross he earned by taking a Hibernian bayonet in the throat is the only necklace she now wears.

She binds the mixture with water from a hollow stone and her own saliva. Not pleasant this, she was brought up not to spit, but she imagines she is spitting into the King’s face, that first time when he came into the shop, and leaned on the counter, and smiled through his golden beard. “If I had known there was such a pretty shopkeeper in this village, I would have done my own shopping long ago.”

She remembers: buttocks covered with golden hair among folds of white linen, like twin halves of a peach on a napkin. “Come here, Madeleine.” The sounds of the palace, horses clopping, pageboys shouting to one another in the early morning air. “You’ll never want for anything, haven’t I told you that?” A string of pearls, each as large as her smallest fingernail, with a clasp of gold filigree. “Like it? That’s Hibernian work, taken in the siege of London.” Only later does she notice that between two pearls, the knotted silk is stained with blood.

She leaves the mixture under cheesecloth, to dry overnight.

Madeleine walks into the other room, the only other room of the cottage, and sits at the table that serves as her writing desk. She picks up a tin of throat lozenges. How it rattles. She knows, without opening it, that there are five pearls left, and that after next month’s rent there will only be four.

Confound your enemies, she thinks, peering through the inadequate light, and the wrinkles on her forehead make her look prematurely old, as in a few years she certainly will be.

(The painting is Sleeping Beauty by Sir Edward Burne Jones.)

November 30, 2013

Making Happy

Lately, I’ve been thinking about happiness, because I’ve been happy. Oh, I’ve also been tired, and sometimes frustrated, and sometimes cranky. But underneath, I’ve been happy, and that’s important because as you may remember, I went through a period of depression about two years ago. Serious, going-to-therapy-every-week depression. Of course, it was while I was finishing my PhD dissertation, which made me feel trapped and miserable, so that makes sense. But my point is that I know unhappy. I remember unhappy quite well . . .

There’s a message I see quite often, particularly on blogs and posted on Facebook: it’s that we alone are responsible for our happiness, and that our happiness depends on how we perceive the world. Not on our material circumstances. And I think that is exactly . . . wrong. Anyone who’s had a bug bite that itches and itches, or can’t set the thermostat so it produces the right temperature, and is always either too hot or too cold, knows it’s wrong. There are a lot of things in our lives that depend primarily on our perception, on the way we process our material circumstances. Success comes to mind: whether or not we are successful really does depend, I think, on how we see our circumstances rather than the circumstances themselves. We can define our own success. Perhaps even contentment, that sense of overall comfort, is primarily mental. Perhaps even joy.

But I believe that happiness is different: it’s a day to day, minute by minute thing. Whether I am happy at any give moment can depend quite a lot on whether or not I am eating a cupcake. If I am eating a cupcake, I am happy. (Depending on the cupcake, of course. I mean, I’m picky.) Happiness does in fact depend on things outside ourselves, so to make ourselves happy, we need to change things outside ourselves. (At least, that’s a lot easier than just trying to be happy, which I think is a very hard thing to do. Make yourself be happy, try to produce an internal state of happiness without changing anything external . . . Much easier to buy a cupcake.)

Here are the things I do to make myself happy, and notice what small things they are, how little it takes:

1. Take a bubble bath! This is my #1 go-to making happy thing, and it’s much more cost-effective than therapy.

2. Do the dishes. No, doing dishes does not make me happy. But having done them does! And this goes for all the other cleaning, straightening, organizing things as well. Making beds, vacuuming carpets, even cleaning the bathroom. Among other things, these get rid of that vaguely guilty feeling that comes from not having cleaned. But they also provide a feeling of accomplishment. You may not have finished your PhD dissertation, but hey, the dishes are done!

3. Buying and arranging fresh flowers. I know these are expensive: I’m lucky to have a neighborhood Trader Joe’s, where I can buy flowers each week. Just looking at them, on the table, the dresser, the windowsill, makes me happy.

4. Eating chocolate. Of course, it has to be the right chocolate: brownie cupcakes from Sweet, chocolate orange hazelnut torte from Burdick, even a Toblerone. But chocolate is a happy thing.

5. Painting toenails. Gold, dark burgundy, iridescent purple. Particularly fun when you know you’re going to be taking off your shoes for airport security. It’s a small sign of defiance: you want me to take off my shoes, security person? I have gold toenails!

6. Reading books. I know, I know, this one is obvious. But I also deliberately choose books that will make me happy. There are a lot of books out there that will make me unhappy, not because they’re sad, I’m fine with sad, but because they are boring or badly written. Good books are happy books.

7. Browsing thrift stores. Also antiques stores, when they’re the sorts of antiques stores in which you can actually afford things, old silver plate and transferware. I believe in retail therapy, as long as you’re doing it in a place where you’re not going to be anxious about the prices. If I can buy myself two sweaters in a thrift store for $10? I’m golden.

8. Waking by the river. I love to walk by my river and check on how it’s doing. Are the leaves turning yet? Have they fallen? What are the geese and squirrels doing? Walking in a natural space is necessary for mental health anyway: you need the sunlight, you need the wind in the treetops. But there is something particularly magical about water. If you can, walk near water. It will make you happy.

9. Listening to music. Another obvious one, but sometimes I forget how powerful music can be. And again, I’m picky. Loreena McKennit, I’ve found, is particularly happy-making.

I’m trying to think of a tenth thing I do to make myself happy, and if I think of it, I’ll mention it later. But these are the ones I could think of, off the top of my head. What I’m looking for is something easy, something you can do at a moment’s notice. For example, spending time with friends makes me happy, but that’s something I usually need to plan for. These are things I can do immediately, when I need to, by myself.

And they work even when there is something important making you unhappy, because external circumstances can do that, in a powerful way. If you feel trapped, if you feel as though you can’t do what you want — that, more than anything, will make you unhappy. Even in that circumstance, bubble baths will get you a long way. They got me through a PhD dissertation (well, and therapy).

This is me, on a rainy day, walking around the city. Being very happy just to see the city in the rain!

October 20, 2013

Having a Purpose

When I walk through the bookstore nowadays (the university Barnes and Noble, where these books are on a front table, by the coffee shop), I see so many books on finding your purpose in life. The other day, I stopped and flipped through them, out of curiosity. I didn’t buy one, because I’ve always had a sense of purpose, as long as I can remember. I don’t need to find one, thanks. But it’s not just in books: there are videos out there, programs on the internet, all on finding a sense of purpose.

I’m not going to write about finding your purpose in life.

The strangest, for me, was a video on living purposefully. If you don’t have a sense of purpose, said the man in the video, you can still live purposefully, mindfully. Which seems like a good idea anyway, but is not at all the same thing. It struck me as strange because living that way was offered as a substitute for having a sense of purpose, as though we all need a sense of purpose. These books and videos and programs all imply that it’s important to have a purpose in life, that without it you’re missing something.

As someone who’s always had a strong sense of purpose, my response is that it’s not, and that having a purpose can actually be — painful, troublesome, disorienting. Keep in mind that this is based on my experience, so someone else who has a strong sense of purpose could describe it quite differently. But here’s what it looks like in my life.

I’ve always known that I was a writer. Not just that I wanted to write, but that I was, at my core, a writer. As a child, I read and told stories. As a teenager, I read and published poetry in the high school literary magazine. As a college student, I read and published poetry in the college literary magazine. I was an English major because I couldn’t imagine studying anything other than literature. As a law school student, I read when I was supposed to be studying for exams, and I wrote a novel. I started publishing poetry in literary journals. As a corporate lawyer, I kept novels in my office desk and read them during lunch. I plotted my escape, when I could return to graduate school to study English literature. In graduate school, I read and read and read, and I went to two summer writing workshops, using my stipend to pay for them. I wrote short stories and started publishing them in magazines and anthologies. After graduate school, I made the decision to teach writing rather than literature, because I was a writer, to my core.

I experience writing not as something I’ve chosen, but as something that has chosen me. I have work I need to do, and that work is writing, and my life is in that work. My purpose in life is that work. If I’m not writing, I start to feel sick, anxious. I start to feel as though I have failed.

I wrote down some of the ways that having a sense of purpose affects one’s life, or at least my life. When you have a purpose,

1. You prioritize that purpose above other activities. Like sleep.

This is not necessarily a good thing, since sleep is important. Eating is important. Having an actual life, other than the fulfillment of your purpose, is important. But all of that can seem unimportant when I haven’t written for a week, and it’s midnight, and I tell myself that instead of going to sleep, I’m just going to look at that story or part of that story, just that one paragraph. I’m not going to revise anything. But as soon as I open the document, I’m gone, into another country — and the next time I look up, it’s three a.m.

2. You make decisions based on your purpose that can make other people wonder what you’re thinking.

Like, for example, giving up a career as a corporate lawyer because I knew I could never be a corporate lawyer and write.

3. You strive for perfection in your art, which is not in fact achievable.

You try to write perfect sentences, perfect stories, even perfect novels. (Trying to write a perfect novel with perfect sentences is a good way to drive yourself mad.) There is no such thing as perfection in prose. There is perfection in poetry, but the only perfect poem was written by John Keats, and you are probably not John Keats, and your poem is probably not “Ode to Autumn,” so you’re probably out of luck. But you’re going to try anyway.

4. You have both overweening confidence in your abilities, and abject self-doubt.

You are smart enough to know your own talent, but also smart enough to feel your limitations and shortcomings. After all, if you have a sense of purpose, you’ve probably been practicing your art in one way or another since you were a child. And you compare yourself to the best that has come before you. So there are days when you say to yourself, I’m not Virginia Woolf, therefore I am a gnat. You are perpetually disappointed in yourself, and yet perpetually working harder to get better at what you do, because you don’t want to be a gnat.

(Are you surprised that writers have breakdowns, after what I’ve written?)

5. Your purpose can, potentially, fill all of your life. All of it, with meaning and striving and fulfillment.

Which is wonderful, except when you realize that there are other things in life as well, like sleep. And eating. And maybe taking a class in Japanese, but not so you can write about Japan in a story. Because it’s so easy to do things only so you can write about them in a story . . . Having a purpose can fill your entire life, which is why I think there are so many books about having a purpose. Because we all want meaning, fulfillment. But it can also substitute for having a life. It can also lead to overwork, depression, breakdown.

So I wonder if having a purpose is rather like having an illness or addiction, and people who don’t have one, or aren’t sure they have one, should instead simply live their lives, and enjoy them? I mean, look at the lives of the great writers, the great artists. Do you really want lives like those? Unless you can’t help it . . .

This is Virginia Woolf. Whom, as I may have pointed out, I am not: