Theodora Goss's Blog, page 21

June 14, 2014

Writing Poetry II

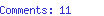

So first, I have a poetry collection coming out, from Papaveria Press. It should be out in the next few weeks? It has a gorgeous cover by Virginia Lee and a wonderful introduction by Catherynne Valente. I’m very, very proud of it. Here is the cover:

At the same time, it’s kind of scary having a poetry collection come out. First, because poetry is deeply personal, more so than prose. Some of it is literally personal, in that it’s about me. Like my poem “The Goblins”:

The Goblins

I have frequented the ways, even the byways of men,

I have gone forth silently, still-countenanced and cold;

they have not noticed clustered at my hem

the tattered-earned smirking little goblins bold.

I have bowed and seemed to smile and seemed to converse with them,

while my face remained pale and my words retained their chill,

and the little goblins chattered and clattered at my hem

in voices triumphant and shrill.

This is about me of course: I have little goblins following me around. Not literally, but as a writer, figuratively, imaginatively. I can hear their voices. Sometimes it’s difficult to live in the real world, because I forget that it’s real. The interior word seems so real so me . . .

But all of it, I take personally, which connects to my second reason. I started writing poetry very early, much earlier than I started writing prose. I have notebooks full of poems I wrote in high school, and I actually had some of them published in the school literary magazine. I thought I was going to be a poet. They’re not particularly accomplished poems, but if I were looking at them today, as a creative writing teacher, I would say, “You have something here, a rhythm and ear for language. Keep going.” Then I went to college and took poetry classes with two famous poets, Charles Wright and Greg Orr, that totally killed my desire to write poetry.

What was so wrong with those poetry classes? Well, I want to learn how to write poetry: I wanted to be told, this week we are studying sonnets, so here is the history of the sonnet, here are sonnets to read, go write a sonnet and make it your own. Let’s see how you do. That’s how I would teach a poetry class. But that’s not what we did. Week after dreary week, students would bring in their dreary poems and we would go around in a circle, workshopping them. If you want to be a poet, you should never, ever start with free verse. Good free verse is actually much, much harder than writing a sonnet, just as good abstract expressionism is much, much harder than representational painting. Of course, bad abstract expressionism and bad free verse are easy . . .

Week after week of bad free verse. And nothing fun or funny or whimsical allowed. It had to all be serious. I did not think of it this way at the time, because I was too young, but there was no sense that poetry had originally sprung from song, that it was a form of entertainment.

So I came out of those classes with the distinct impression that what I wanted to do was not worth doing. The poetry I wanted to write was not worth writing. It took years and years of writing and actually publishing poetry, of people telling me they liked it, for me to believe it was worthwhile. And more than that, it took me years and years, working alone, to learn how to write the poetry I wanted to write. I’m still learning.

I think the first poem I ever wrote that I was actually happy with was this one, “Beauty to the Beast”:

Beauty to the Beast

When I dare walk in fields, barefoot and tender,

trace thorns with my finger, swallow amber,

crawl into the badger’s chamber, comb

lightning’s loose hair in a crashing storm,

walk in a wolf’s eye, lie

naked on granite, ignore the curse

on the castle door, drive a tooth into the boar’s hide,

ride adders, tangle the horned horse,

when I dare watch the east

with unprotected eyes, then I dare love you, Beast.

It was also the first poem of mine published. It’s not the sort of thing I could take into one of my college poetry classes, because in those classes, poetry didn’t dance. I want my poems to dance.

So in the poetry collection, there are poems that are supposed to be fun, or funny, or whimsical. There are several that are really for children. There are many that are quite serious and for adults. Many are about what it means to be a woman, about love and death and loneliness. There are several that have already been set to music. They are influenced by all the poets I love, Walter de la Mare as much as T.S. Eliot. They are the poems I wanted to write . . .

I don’t have any great insight to end with, other than the one I think underlies everything I do, and all these blog posts: you must do what you fear, every day. Courage is a muscle, and if it’s to become strong, you use must it. And I guess there is a bonus insight here: you must have the courage to find your own voice, your own style, even if no one can teach it to you. I’m still finding mine.

I’ll end with two things. First, an offer: Papaveria Press is generously making the Advance Review Copy of the poetry collection available, as a PDF file, to anyone who wants to review it, anywhere. So if you’d like to read the poetry collection and are willing to post a review, whether it’s on a blog, on Amazon or Goodreads, or in an official publication, I can send you the ARC. All you need to do is contact me, in the comments section below, on Facebook or on Twitter, and tell me where you would like me to send the file. And then, post a review . . .

Second, some time ago I made a YouTube video of me reading the first poem I posted above, “The Goblins.” Here it is, if you’d like to see it!

June 8, 2014

Living in Budapest

I know, I haven’t been blogging regularly. I try to write a blog post each week, to post on Saturday or Sunday. And that hasn’t been happening.

It’s because I’ve been living too hard, and writing hard too. And that doesn’t leave much room for blogging. In May, I finished the university semester, which means that I turned in my grades and wrote to my students one final time. Then I started packing. Today I am writing this post in a cafe in Budapest. I’ve been here for a week and a half, and will be here for another three weeks. Usually when I’m in Budapest, I’m a visitor: I go around to see the sights. But this time, I’m a student, taking an intensive course in Hungarian, trying to relearn my native language, the language I spoke until I was about five years old, when my family left Hungary. So on weekday mornings, I go to school for three hours. And then in the afternoons, I study.

Also, I work on the novel. In case you were wondering, it’s going very well. I have over 100,000 words written, and they’re close to the right words, which is the important thing. This weekend, I should be able to finish this particular draft, which will mean that I have an entire draft of the novel written. Then, I will revise. And then it will go to readers for feedback.

Studying Hungarian and writing a novel don’t leave much room in my brain for anything else!

But I wanted to write about what it’s actually like to live here, rather than just visit. It feels as though I’m doing all the things I would be doing at home in Boston: shopping for groceries, going to school (although here I’m a student rather than a teacher), trying to make sure I have the basic things I need (like plates, towels, wifi). So I’m going to include some pictures and try to describe what my life looks like, here in Budapest.

Below is my pretty little street. The cafe on the street is called the California Coffee Company. One difference between my schedule here and in Boston is that here, I wake up at 5 a.m.! Because across the street is the park around the Nemzeti Múzeum, and in the park there are tall trees, and in those trees live birds. They wake up at 5 a.m., and they wake me up too. It’s like a bird alarm, and there is no snooze button! So I wake up, and eat breakfast, and study Hungarian. When the California Coffee Company opens at 7:30 a.m., I go get my tejeskávé, which is a latte, and do whatever needs doing with wifi. By the time I’m done, it’s time to leave for school.

And this is the museum itself. The statue is of a famous poet, János Arany, because in Hungary poets are very highly thought of, and they get statues made of them, and squares named after them. It would be nice if we did this sort of thing, wouldn’t it? My school is across the Danube, so I walk across the Szabadság Bridge to Buda. (Budapest is two cities, Buda and Pest, separated by the Danube. Rather like Boston actually, with Boston on one side and Cambridge on the other. It’s funny that, in the United States, I ended up living in the city most like Budapest.) And then it’s Hungarian for an hour and a half, with a break, and then another hour and a half. My class is ten students, from all over the world: there is a doctor, a folk singer, a businesswoman. They come from countries such as Italy, Switzerland, Japan. And of course the United States. The class itself moves quickly: during the first week, we covered over a hundred vocabulary words, the objective case, and how to pluralize both nouns and adjectives. We were expected to know numbers up to a million. How to count money, make phone calls, buy produce in the shops. How to have a basic conversation.

Hungarian is what a language would look like if it were created by a mathematician who is also a poet.

It’s a particularly difficult language to learn because it’s not Indo-European. It came down from the steppes with the Magyar tribes, who were nomadic horsemen. In Hungarian, you say that a person lives in another country: Amerikaiban. (“Ban” means “in.”) But you say that a person lives on, not in, Hungary (Magyarországon). Because the early Hungarians did not think of themselves as living in a country. Other people lived in countries: the Magyars lived on their hills and plains. It’s part of the Finno-Ugric groups of languages that includes, basically, Finnish and Hungarian. In Hungarian, most of the grammatical work is done by suffixes, so you need to know which suffixes to use for different tenses and cases. Word order is important for emphasis. And then, there’s the poetic part: the suffixes change vowels so that the vowel sounds harmonize. In other words, the plural of tomato (paradicsom) is paradicsomok. But the plural of gyerek (child) is gyerekek. Because o is a back vowel, and e is a front vowel. So ok and ek just . . .sound better. In order to make a word plural, you not only need to know the ending, you also need to know which vowel to use. And there are fourteen vowels. (In French, you can talk about the vowel e, taking several different kinds of accents. In Hungarian, e and accented e actually function as different letters.)

One things that saves me, in particular, is that Hungarian is almost entirely phonetic: if you know how a word looks, you can pronounce it. Pronunciation often trips up Americans, but mine is actually pretty good. So I can say things like “viszontlátásra” (“goodbye,” technically “see you later”) without tripping up.

This, by the way, is a Puli, a traditional Hungarian herding dog. I see him sometimes as I head home, back across the Danube. His dreadlocked hair keeps off the rain, and is said to protect against wolf bites. I think that if a wolf took one look at a Puli, it would be so confused that it would slink away, trying to figure out what in the world that was and what one does to it . . .

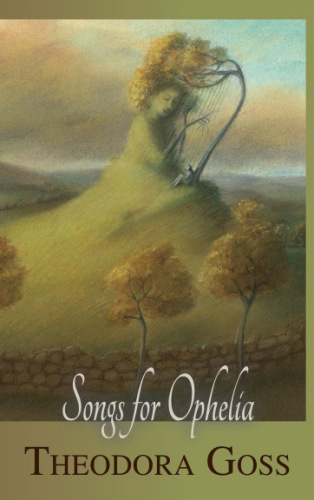

And this is what my lunch might look like. Kifli (the bread, which has a specific name), with a paprika and ewe cheese spread, pickles, smoked cheese, and cherries. Food in Hungary tastes completely different from food in American, or England, or even Austria. It has its own distinctive flavor: less sweet, more complex. When I’m not here, I miss it.

And then it’s time to do my own work (mostly writing just now, although I also have to start preparing for my summer residency with creative writing students). And of course to study Hungarian. Honestly? It’s difficult sometimes. I’m a terrible introvert, and I have to force myself to have conversations in Hungarian. It would be so easy to pretend I don’t know any, just speak English. Most people here know enough English that I could get by. It’s embarrassing to make mistakes, and I’m sure I make many more than I’m aware of. But I make myself say “egy tejeskávét kerek” even though I’m not sure it’s right. I tell salespeople that I’m learning Hungarian, even though I don’t speak well (“magyarul tanulok, de nem jól beszélek). As I walk down the street, I sound out the signs. Whenever I see a number, I make myself say it. Because the best way to learn anything is to live with it. Or on it . . .

Here, finally, is a picture of me with my river, the Danube. In the distance is Castle Hill. It’s lovely to be here, and although I know my stay here is temporary, I’m glad that it feels as though I’m living here, not just visiting. It’s good to be “Budapesten.” Which, yes, means on Budapest . . .

May 18, 2014

Making a List

People keep asking me how I can do all the things I do, and the question always surprises me, because from my perspective, I don’t get nearly as much done as I’d like to. But it’s true that my life is very, very full, and I do use specific strategies to get as much done as possible. So I thought I should write about what I do . . .

Sometimes the answer is that I don’t. I miss deadlines, get things in late, fall flat on my face. Fail. That happens. Sometimes I forget things I shouldn’t have forgotten. And then I remember and have to apologize . . . But when it does work, how does it work?

This is what my life looks like: I teach full-time in the academic writing program at Boston University, which is a major research university, and I’m a faculty member at the Stonecoast MFA Program, which means that I mentor graduate creative writing students. They are both jobs I love and feel incredibly lucky to have. I’m also a writer, so I’m always writing — and I usually have a deadline of some sort, because most of what I write at this point is solicited. People ask me for stories, which are due on particular dates because the anthology has to be edited and go to print. This year, I’ve also been working on a novel, which is almost done. That’s taken a lot of time . . . And I have a ten-year-old daughter who is with me part of the week. Today, for example, I’m writing this blog post, I’m going to the library with my daughter to return books, I need to do some work on the poetry collection that should be coming out this summer, and I’ll be reading over material from one of my creative writing students. Then, I’ll work on the novel. I want to get the entire novel down on paper (this will be the second draft for most of it, although the first draft for the last few chapters) before I leave for Budapest in a little more than a week. In Budapest, I’ll be taking four weeks of intensive Hungarian, with the hope that eventually I can relearn enough Hungarian to translate fairy tales. Before I leave, I need to finish some administrative stuff for Boston University and . . . oh, never mind, it’s going to take too long to describe it all. Let’s just get on to the How To. I think there are basically three things I do:

1. Prioritize.

2. Organize.

3. Simplify.

You have to prioritize ruthlessly. I mean in part that you need to learn to say no, usually to people you like and want to help. You have to learn to say, “No, I can’t get you a story by then,” or “No, I can’t meet with you that week.” You can’t do everything, so you have to figure out what is most important for you to do. You have to know what your priorities actually are . . . More on this in a minute.

(Priority: having a beautiful apartment justified bringing this little table home from a thrift store. I carried it for about a mile . . .)

It helps a lot to be organized. To have particular places where things always go. I have a binder for my Boston University teaching that contains all my notes. A folder for my Stonecoast teaching. Separate folders set up for each on my desktop. In my apartment, there are spaces for specific things, and when things are out of their spaces, I put them back. I’m not naturally an organized person — I don’t think any of us is, naturally — so I got into the habit of being organized, of doing the dishes before I went to sleep, making the bed when I got up. Organization is a habit, like exercise. Once you get into a habit, it’s more trouble than not to follow it. If you want to do anything, make it a habit . . .

And it’s essential, I think, to simplify as much as possible. There are things I need to do that I don’t want to spend a lot of time on, because they’re tedious and don’t really contribute to either my joy in life or accomplishing my goals. So I try to make them as simple and automatic as possible. Like paying bills, or doing taxes.

I try to create a life in which I’m spending most of my time doing what I actually want to. Oh, I may not want to do every single thing connected with my projects — I don’t wake up wanting to grade 50 papers or go over copyedits. But those things contribute to my overall goals. When I do them I get a sense of accomplishment, because they’re helping me accomplish the things on the list.

(Priority: I didn’t list this below, but one of the items on the list is traveling to fabulous places. These are Hungarian forints. And I’m actually related to the man on the 20,000 forint bill.)

What list, you ask. The list. The one I keep on my cork board, where I can see it every day. As I’m writing this, it’s up and to the left of me. If I look up and turn my head a little, I can see it. It’s a list of the things I want to accomplish in life, and there are eight items on it. I starting making the list about two years ago, when I realized that I was working a lot . . . but toward what? What did I really want to accomplish? I found that I was trying to do everything, and prioritizing by what other people wanted from me and when it was due, rather than what I actually thought was important. So I started making the list.

I’m not going to tell you everything on it, because some of it’s private. But here are some of the items listed. (Fair warning: these are ambitious. Remember that they are the things I want to accomplish in life. Not next week. When you make your list, be ambitious. You don’t have to tell anyone else how ambitious you’re being. The list is for you.

1. Become a great and popular writer.

2. Create a fulfilling career teaching writing.

3. Have wonderful friendships with fascinating people.

4. Have a wonderful relationship with my daughter.

5. Create a welcoming and beautiful home.

That’s enough to talk about, right? By “great” writer I mean that I want to be as good as I can possibly be, in terms of the actual craft — I want to write as well as I can. By “popular” I mean that I want people to read what I write. I told you it was ambitious! And notice that these aren’t all career goals. I want to have good friendships. I want to have a lovely home. And of course I want to be close to my daughter. The list contains my priorities. I made it by asking myself, if I got to the end of my life, would would I feel as though I had missed out on, if I had not done it?

(Priority: going to see the lilacs at the Arboretum with my daughter, on Mother’s Day.)

The reason it’s on my corkboard is that, if it wasn’t, I might forget what my priorities are. Having it where I can see it every day means not only that I don’t forget, but also that every evening, I can look at the list and ask myself, what on the list did I work on today? If I graded papers, or went out for a cupcake with my daughter, or made the bed and did the dishes, I mentally pat myself on the back for having worked on an item on the list. I recently had to add something to the list, which brought me from seven to eight items:

8. Be healthy and beautiful, inside and out.

By beautiful, I don’t mean a culturally constructed idea of beauty. I mean my own idea of beauty, which means being healthy and comfortable in my own skin, looking like the self I want to be. I added this to the list because I realized that I was neglecting exercise and sleep. I was prioritizing other items on the list, staying up too late, which inevitably led to cookies in the middle of the night and being too tired to exercise the next day. Putting it on the list meant I had to think about it, work on it, make it part of my life. If I exercise in the morning, and eat my vegetables, and take a nap in the afternoon to make up for the late night (because yeah, I’m still not so good at going to bed early), I congratulate myself for working on item #8.

I try to work on most items on the list, most days.

So there you have it. I mess up, I miss deadlines, my email inbox is a triage unit. But I have a list of priorities, and I try as hard as I can to make sure that the rest of my life is focused on fulfilling them.

(Priority: feeling healthy and beautiful, and at ease with myself.)

April 12, 2014

Challenges and Strengths

Recently, while I was having dinner with a friend, she said to me, “You know, you have beautiful skin.”

It’s a compliment I’ve heard before, and usually I just say “Thank you.” But this time, because I’d been thinking about the subject of this blog post, I said, “It’s because I have acne.”

She looked at me as though puzzled, and said, “I don’t see any acne . . .” So I had to explain. I’ve had acne since I was a teenager, and for a long, long time, I didn’t know what to do about it. My skin would break out regularly. It was not terrible; I’ve seen much worse cases. And my skin didn’t scar from it. But it was painful and embarrassing. (Anyone who thinks acne is just a cosmetic problem has never experienced it: breakouts are actually quite painful.) It was only in my twenties, when topical benzoyl peroxide creams became available, that I was able to get it under control. Over the years, I developed a skincare routine that worked for my sensitive, acne-prone skin. So, since my twenties, I’ve had to take excellent care of my skin. I’ve had to know what I was putting on it and why. Otherwise, breakouts.

Since my twenties, I’ve followed an invariable routine. Morning: cleanse, exfoliate, tone, moisturize (with a benzoyl peroxide cream). Then sunscreen (since the cream makes my skin more sensitive to the sun), or makeup with sunscreen in it. Night: cleanse, exfoliate, tone, moisturize (with the same cream). I’ve never gone without sunscreen, or to sleep with makeup on. I’m at the age now where I’m starting to get fine lines. But my skin feels clean and healthy, which is what’s most important to me.

I honestly don’t think it would be in as good shape if I didn’t have acne.

I was originally going to call this blog post “Flaws and Strengths,” but I don’t think my acne was as much a flaw (although I certainly experienced it as one — I felt flawed) as a challenge. And I’ve noticed that the places I’m strongest are the places where I’ve had to overcome or learn to manage challenges. (You can’t always overcome them — I haven’t overcome acne. I’ve just learned to manage it on a daily basis.) Once I started thinking about this topic, I started compiling a list of my personal challenges, the ones I’ve had to overcome or manage in order to become the person I am now. At the top of the list was “shyness.” I was a shy, introverted, sensitive child. The world isn’t a very easy place for a child like that, particularly if she’s also smart and ambitious. You don’t get through law school or a PhD program being shy and sensitive! One of the hardest things I had to do, as a graduate student, was teach: it was just me, in front of a group of twenty undergraduates, for an hour. Several times a week, for an entire semester. Before each class, I used to prepare so thoroughly that I barely needed my notes and could go off on tangents. That’s easier to do if you’re really, really prepared. And before each class, I used to have a conversation with myself, in which I reminded myself that I was a good teacher, that I should have confidence in myself. (Seriously, I would have to talk myself into confidence.)

Shyness is a problem in a writing career as well, of course. I used to prepare in the same way, talk to myself in the same way, before panels. I also used to request as many panels as I could, because I figured that if I was afraid to do something, I should do it as much as possible. If I did it enough, I would no longer be afraid. And it worked . . . I’m no longer shy, although I’m certainly still introverted. After a day of teaching (which now usually involves three classes, or a long and intensive workshop), I need time alone. I can be quite anti-social . . .

Another challenge on my list was going for a very long time in my life with very little money: through college, then law school, then graduate school. Even when I was a lawyer, making the most money I’ve ever made in my life (I don’t make anywhere near as much now), I was sending most of it to the loan companies to pay off my law school loans. I had incentive to live off as little as I could. (That’s why I decided not to call this post “Flaws and Challenges”: lacking money is certainly not a flaw, although society often makes us think it is.) But I learned to be thrifty. I love beautiful things, so I learned how to find or create beauty without spending much money on it. How to buy furniture from thrift stores, or even in some cases find it by the side of a road, then repair and paint and refinish. How to find clothes I loved and that made me happy on a very strict budget. All the different ways in which one can save money, and what one really needs. (I learned the valuable lesson that I can feel quite rich as long as I have the necessities, by which I mean things like a can opener, and small luxuries, by which I mean a beautiful teacup or scarf.)

We are strongest where we have been challenged, just as bones are strongest where they have broken and then healed. It’s how we respond to the challenges, the way we overcome or manage them, that makes us strong. I think that’s because we don’t really like growing, becoming stronger. It’s uncomfortable. We don’t like having to conscientiously take care of our skin, or exercise and eat right very day, or budget carefully. We only do those sorts of things when we have to. Challenges force us to.

Make a list yourself: what are your challenges, how have you dealt with them? I bet you’ll find that having dealt with them has made you stronger. At least, that’s my hypothesis.

(The photograph is of me on an overcast spring day in Boston. I took it to test the light, but then decided I liked it as a photo even though I’m so solemn in it. In that cold, gray light, my skin looks luminous . . . I particularly like the pink scarf which, yes, was bought at a thrift store. It always gives me a sense of satisfaction to find a pashmina for $2.99!)

April 6, 2014

Traveling Light II

I haven’t written a blog post in two weeks because, two weekends ago, I was at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in Orlando, Florida, and there was simply too much going on for me to write one. And the weekend after that, I was still recovering from having been gone for a weekend, which of course put me terribly behind on my work. But it was worth it.

I’ve been wanting to write, for a while now, about traveling light. I started thinking about this topic while I was packing for ICFA, and I’ve been thinking about it since because in July, after I get back from Hungary, I will be moving to a new apartment. So part of what I’ll be doing between now and then is going through all my stuff, figuring out what I want to keep and what I don’t. Because both when I’m going someplace and in life generally, I prefer to travel light. When I tried to title this post, I had to title it Traveling Light II, since I’d written a post called Traveling Light several years ago. Evidently, this is something I’ve been thinking about for a while.

In this post, I’ll include some pictures from ICFA. Right now, Boston is in the middle of our typical long, cold spring. So it’s funny to post these pictures of Florida, where it was warm and I was careful to wear plenty of sunscreen.

Also, there was an alligator. (I didn’t see it, but a friend of mine took a picture later that weekend. So it was there. Please do not feed it.)

So, traveling light. It means packing what you need, and no more than that. I’m actually not very good at packing lightly for a conference like ICFA, because I’m never quite sure what I’ll need. At this particular ICFA, I needed t-shirts and summer skirts for outdoors, and sweaters and shawls for inside the hotel. I also needed a banquet dress, because there was a banquet. I needed flats for the day and heels for the evenings. The convenient thing about being female is that all your clothes fold up small: it’s easy to pack t-shirts and scarves. It’s hard and inconvenient to pack heels, and yet I didn’t want to go without them, because vanity. And the inconvenient thing about being female, at least for me, is that I needed things like face wash, and sunscreen, and shampoo. And I needed my own, because my skin is the sensitive kind that, if you use any old thing on it, turns against you. I always have a bag to check at the airport.

(This is me with three writer friends: Bo Bolander, Francesca Myman, and Valya Dudycz Lupescu. That skirt is one of my thrift store finds.)

But in general, I try to travel light, and I won’t be packing that much more heavily for my month in Hungary than I did for my weekend in Florida. My suitcase will be full, rather than only about half full, but I’ll have the same sorts of things: black t-shirts, three summer skirts, two pairs of jeans. Sneakers, flats. Pajamas. In Hungary, I’ll be able to do laundry, and I know where to buy things if I need them. Anyway, the most important things remain the same, whether I’m packing for three days or thirty: my laptop, my phone, credit cards. Identification. Pens and my Moleskine notebook.

(This is me with another writer friend, Sofia Samatar. What I’m wearing: black t-shirt and cotton skirt, so I’ll be fine outdoors, and a black swingy sweater for the cold hotel rooms. I also have a shawl if I get too cold. The coral necklace belonged to my grandmother.)

I’ve never quite seen the point of having more than you need, and I suppose traveling so much has reinforced that in me. I’ve always been very happy going away somewhere, living out of a suitcase for a while. There’s a sense of lightness about it, the sense that you can leave your stuff behind and still be fine, that your stuff does not define you. Don’t get me wrong, I love my stuff. But I try to live by the William Morris principle: I try to make sure that everything I own is either useful or beautiful. So yes, I do have some things that are not, technically speaking, useful — that I don’t necessarily use. Like seven pairs of vintage white gloves (some kid, some lace). But I put them in the beautiful category. And if something is neither so useful that I actually use it, nor so beautiful that I can’t bear to part with it, then I part with it. Because it’s only going to weigh me down. So that’s what I’ll be doing between now and July: sorting through my stuff and making sure that everything I have is something I want to move to the new apartment. (Well, except for June, when I’ll be in Hungary. Living out of a suitcase.)

(This is me at the banquet on the last night of ICFA, with Nancy Hightower and Valya Dudycz Lupescu. I’m wearing the banquet dress, which I bought at a thrift store for $15. It needed to be cleaned, and the zipper needed to be repaired, but I think it turned out very nicely!)

It’s funny how sayings we hear influence us. There’s one I think about a lot: “Shrouds have no pockets.” It’s supposed to be Irish, and it does sound best if you say it with an Irish accent, in which “shrouds” has at least three syllables. What it means, of course, is that you can’t take anything with you. And of course you can’t. So there’s no reason to hoard anything you don’t actually use or enjoy: it’s not going with you anyway. Having too much stuff often means wasting time taking care of it. I want to have just enough to live a lovely, elegant, comfortable life. More than that isn’t necessary.

When I said that I preferred to travel light, someone said, “I thought you meant in terms of emotional baggage.” And yes, I suppose that’s another way of thinking about it, but I think it’s much harder to get rid of emotional baggage than it is to get rid of material things. Imagine if we all had to check our emotional baggage at the airport: we would have to pay so much for the extra weight! As I’ve said before, we live metaphorically. We live as though the world were magical, whether it is or not. (I think it is, but won’t quarrel with anyone who thinks otherwise.) I know a woman who lost her home at a young age; now, as an adult, she owns four houses. She doesn’t need four houses, and most of them stand empty most of the year. No one needs four houses . . . They are material responses to her emotional baggage.

So I honestly think the best way to deal with emotional baggage is to clean your physical space. It’s like a spell: a physical action that has a psychological consequence. Several years ago, when I was going through some very difficult things psychologically, I left the country. I went home to Hungary, to my grandmother’s apartment, where I had lived as a child. It was a symbolic way to deal with my problems, and you know, it worked. There was not enough room in my luggage for psychological problems: there was barely enough room for pajamas and shampoo. So I left my emotional baggage behind. When I came back, it was so much easier to deal with, because my brain was cleaner, clearer, for having been away, for having lived out of a suitcase for a while.

(This is me in a hotel bathroom mirror, at 5 a.m. before I need to catch a shuttle to the airport. On two hours of sleep. I returned to so much work, and yet, it was worthwhile getting away. I think we all need to get away, sometimes.)

A month ago, a friend of mine died unexpectedly. Yesterday, another friend died, also unexpectedly. It was the sort of thing where he’s eating dinner at a restaurant and feels a sharp pain, and by the time he arrives at the hospital it’s already too late. Several hours later, he’s dead of a heart attack. So sudden. They were not close friends, so I don’t feel the aching sorrow you feel when family members or close friends die. But they were friends I communicated with regularly, mostly on social media. And they were both about my age. So what I feel more than anything else is a sense of shock. It’s shocking to lose people so young, so suddenly. It’s like having cold water thrown at you. It’s like having Death come for Everyman. You realize that you could be next, and shrouds have no pockets.

So what do you do? Well, you certainly don’t focus on STUFF. No, you focus on your work and art, on creating the things you create, because those are what you’ll leave after you. And you focus on living as fully as you can, on talking to friends and feeling the sun on your face. On traveling to Hungary for lessons in Hungarian (which is why I’m going), and buying white gloves you’ll never use simply because they’re beautiful, or a banquet dress even if you’re not sure whether you’ll be able to use it for more than one banquet. On reading books (I always bring books, although luckily there’s an English bookstore in Budapest). Or of course, if you’re me, writing them . . .

My last photo is of me in Florida, with the sun on my face. Walking around, looking at the trees and water, watching lizards on the balustrade. It’s a photo of me being happy, feeling light . . .

March 15, 2014

My Writing Life II

This past week, I read a blog post on Terri Windling’s blog: “Being Normal is Over-Rated.” In it, she quotes from the writer Dani Shapiro on the writing life:

“I need to live by certain rules in order to protect my writing life. When I was starting out, I didn’t understand this. A friend would call and ask me to lunch or, worse, breakfast, and I’d jump at the chance to get away from my desk for a couple of hours and join the world of real people eating real meals. I convinced myself that I had enough discipline to go out for a bit and then return to my desk, perhaps even invigorated and refreshed . . . and then, an hour or two later, I’d discover that my work day was over. . . .

“Our work requires us to adhere to certain rules — not because we’re rigid or self-absorbed as frustrated friends or family might secretly think — but because it’s the only way we can do it. If we are deep inside a story, we’re in another world — the world we’ve created — which, for the time being, is where we need to live if we are to make it real to ourselves and, ultimately, to others.

“I used to be angry with myself for my inability to live a normal life with normal rhythms and also be a writer. But I’ve come to believe that normal is over-rated — for artists, for everyone. When I was writing Devotion, all but the most essential tasks fell away. My hair got too long; I skipped my annual mammogram; the dogs’ nails went unclipped; the windows didn’t get cleaned; I lost touch with friends. But I took care of my family, and my book got written. That was all I could manage. . . .

“Be a good steward to your gift. This is the first sentence on a list I keep tacked to the bulletin board in my study, an impeccable set of instructions left by the poet Jane Kenyon.

* Protect your time.

* Feed your inner life.

* Avoid too much noise.

* Read good books, have good sentences in your ears.

* Be by yourself as often as you can.

* Walk.

* Take the phone off the hook.

* Work regular hours.

” . . . Cultivate solitude in your writing space, your car, at the kitchen table when the house is empty. Get your blood moving, get your feet on the earth. Your mind is not floating in space but connected to a body. Kenyon wrote this before the lure of the Internet became like crack cocaine for most writers so I would add, ‘Disable the Internet.’ Find a rhythm. This is wisdom from a poet who died too young. I never knew her but she has helped me as much as anyone I have ever known.”

I love this, but rather in the way I love a story about a place I may never visit or experience for myself. It’s a vicarious pleasure, a dream of a writing life so very different from mine. I wish I could have that life, where you can stop doing everything else and just concentrate on your writing. That’s not my life at all . . .

So what is my writing life? First, let’s be realistic. The number of people who get do to nothing but write is small. The number of people who get to do that because they make enough money from writing is vanishingly small. When you see a writer who just writes, there are four possible scenarios: the writer has inherited family money (this is a lot more common than you would think or than I thought possible); the writer is being supported by a spouse (again, very common); the writer is making money from writing, but his or her primary income comes from freelance writing, usually nonfiction for corporations, writing the corporations will own; and the writer makes enough money by writing only what he or she actually wants to write. That last scenario is very, very rare, statistically. So what do most writers do? Well, they work.

Writers work at all sorts of different things. And there seem to be two broad ways of thinking about what writers should do. One is that writers should work at something they don’t have to think about too much, that really is a day job, so they can leave it behind at the end of the day and write. The other is that writers should find a job that fits with their writing, that informs their writing — like, teaching writing. What you choose depends on your personality, of course — and also on the choices you have. I chose the second path, teaching writing. It was a choice I could make partly because I had spent long years in graduate school doing a PhD, because nowadays it’s very hard to find a teaching position without an MFA or PhD after your name. But also, I’m no good at doing things that I’m not invested in. I knew that the “just a day job” track wouldn’t work for me. And honestly, many of the writers on that track would very much like to get off it. Those sorts of jobs are often very hard work, not much fun, and badly paid. They do it for the same reason most writers work: rent, food.

I’m very happy with the choices I made: the PhD was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but I love teaching. I actually have two teaching jobs: one at Boston University, where I teach undergraduates, and one at the Stonecoast MFA program, where I teach graduate students. It’s hard, intense work, and it does involve the same parts of my brain that write, so after a full day of teaching, it can be hard to sit down and write fiction. But I would not give up either of them. Still, it does mean that my writing life looks very, very different from Shapiro’s. What does it look like? Well, every day is different, but there’s preparing to teach classes, teaching classes, holding office hours, commenting on papers. Dealing with all the administrative things involved in teaching, such as writing letters of recommendations. For my work with MFA students, there’s mentoring students on their creative writing, guiding the preparation of senior theses, preparing for the twice-yearly intensive residencies where we workshop student manuscripts. It’s certainly not a day job (or I would not have been up until 3 a.m. last night doing it). I love it, but when do I write? Well, the answer is, whenever I can.

I write late at night after all the other work is done. On the weekends, I spend time with my daughter, and then when she’s asleep, I write. During the summers, when I’m only teaching at one program, I have more time. That has only been true of the last two summers: before, I was finishing my PhD, and had no time to do anything but work on my dissertation. But the last two summers, I’ve traveled and done research for the novel I’m currently writing. I know, it sounds so fancy: going to London for research. And it was, but also, I don’t think I could have written this novel without it. I’m almost done with a second draft, and it’s taken so long in part because I had to learn how to write a novel, this novel. And in part because I had so many other things to do.

I’ve tried to arrange the other parts of my life to support my writing life. That is, I’ve tried to simplify all the parts of my life that aren’t working or writing. I live in one of the most expensive cities in the world, but I do try to live as inexpensively as I can. When I spend money, it’s on food or books. I don’t have a television. I don’t eat out, unless it’s with my daughter. I splurge on a museum membership, the occasional ballet or concert, fancy coffee. Face cream, flowers. When I travel, it’s to conferences or for research. (Anyway, to be honest, for me the perfect vacation would be going somewhere to do research or write. Because that’s what I find interesting.) It’s a lovely, intense life — I wouldn’t trade it for anyone else’s, and I feel very lucky that I get to do what I do. But it can also be very tiring!

So, I’m going to give very different advice from Dani Shapiro. It won’t be applicable to every writer, but I think it will be applicable to a larger group. If you want to be a writer?

* Learn how to write whenever and wherever you can. Create a writing space for yourself. This is not an external space, but an internal space: where you can go in order to write, even if you’re in the middle of an airport. Breathe, go to your internal writing space, write.

* Work irregular hours: that is, if midnight to 2 a.m. is the time you have to write, write then. Try to get enough sleep. Try to eat enough food. Make sure your laundry is done. Accept that your life may be irregular. Accept that it may be irregular for a long time.

* Learn how to live a normal enough life that you can make money to pay rent and buy food. The normal enough life is the price of having a writing life. Writing is cheap, compared to being an opera singer. But you still need a roof over your head, a computer, paper and ink. Internet.

* Learn to live cheaply. If someday you make a great deal of money from your writing, you will have learned good spending habits: you can buy the cheapest castle in Scotland. Until then, learn how to shop at thrift stores, and tell yourself it’s more interesting, more charming, more chic to shop at thrift stores than in department stores. And it is, really.

* Forgive yourself for all the things you’re not going to do, for the email messages you’ll respond to weeks or months late, for the things people will ask you to write that you don’t have time for, the friends you can’t meet for coffee, not that particular week or month — for all the things that will be late (and they will be). Apologize and move on. You don’t have time for guilt.

* Keep writing. If you wait for the perfect conditions, they will never come. If you try to create the perfect conditions, you will probably fail. Learn to write under less than perfect conditions, under the most imperfect conditions. And keep writing.

(This is the writer at her desk. Writing.)

March 8, 2014

Defining The Lady Code

Some time ago, I wrote a blog post called “The Lady Code.” In it, I pointed out that there is still a “lady code,” an implicit code by which we determine whether or not a woman is a lady. This code dates back to at least the Victorian era: in Victorian novels, characters always seem to know, immediately, whether or not a woman is a lady “by her dress and manner.” (I don’t remember where those words come from, but most likely a Sherlock Holmes story?)

Here is what I wrote in my last blog post: “In American, we are raised with an implicit lady code, because we tend not to talk about social status. But upper-middle class girls are educated into it: they are taught what to wear, usually by their mothers. They are taught which skirts are too short, which shirts too tight. They are taught to signal their social status in coded ways.” I added, “So dressing, for a woman, is a complicated affair. When you look into your closet in the morning — and even before that, when you buy your clothes in a store or online — you are making a choice about what you want to communicate. You are speaking in a coded language. If you were raised by an upper-middle-class mother, you know the lady code. You are fluent in that particular language. You know that what you wear should vary depending on the occasion. You will not wear a cocktail dress to the ballet.”

I’ve wanted to write more about this topic for a while, because I’m fascinated by the various ways we communicate, including through clothes. And what I’ve wanted to focus on is that last bit: not wearing a cocktail dress to the ballet. In other words, the details of the code. You see, I was born in Europe, so a lot of the code, and how it applied in a modern American context, I had to figure out for myself. My mother was very strict about how I dressed, but her ideas came from her own mother, who was a lady in the old European sense. What I learned was very old-fashioned. How old-fashioned? As a child, I was taught to embroider, because that is what girl children learned . . . My grandmother told me that only gypsies wore earrings. That old-fashioned.

But I had to learn how to dress, and how dress codes operated, because I was trying to present myself as an educated, employable woman in modern America: first as a lawyer, and then as a professor. This post is about what I learned, how I think the code works: what upper-middle-class women teach their daughters, and what I will probably teach my own daughter. (Please note that in this post I am neither criticizing the code nor saying that anyone should follow it. I’ve rebelled against it plenty myself: when I was sixteen, I pierced my own ears, with safety pins. But the code exists, and we are judged by it. So I’m trying to understand it.) Here are some of its basic tenets:

(The images in this blog post are all, obviously, of Audrey Hepburn. I chose them because she is such a perfect representative of the lady code, partly in how she was presented by Hollywood, but mostly in what she herself chose to wear. So I’ve selected photographs in which she at least seems to have been caught off guard, in her own clothes.)

1. Your clothing should be appropriate for the occasion. You actually find this explicitly stated in Agatha Christie stories, where Hercules Poirot has some wonderful pronouncements about what ladies do and don’t wear. A lady, he says, will always dress appropriately: she will not wear city clothes in the country or vice versa. I would say that dressing inappropriately for a particular context marks you as not understanding that context, whether it’s the ballet or, more importantly, a job interview. It signals that you don’t understand the code at work in the situation. What it sometimes means is that you don’t get the job, and that is, after all, the lady code’s most important ramification nowadays: it affects employment prospects. But more broadly, a woman who is what we call well-dressed will wear rain boots in the rain, flip-flops at the beach rather than on city streets. She will be dressed “appropriately.”

2. Your appearance, including makeup, should be “natural.” By “natural” I don’t mean natural: culturally, we actually think of a bare face, a face with no makeup on it, as a rebellion against social norms. (Which is ironic, since in the Victorian era, a woman wearing makeup would not be considered a lady. Oh, women did wear makeup, but it had to be so discreet as to be almost invisible. And never mentioned!) “Natural” means that you look like the cultural idea of natural: discreet makeup, hair a color that could be natural even though it’s probably not. Nails neatly trimmed but either unpainted or, if painted, a light color that looks, at first glance, like a natural nail. No obvious tattoos. (Tattoos on women have become more accepted recently. But socially, they are still judged. They will still affect important aspects of one’s life, such as job prospects. They remain markers of social class.)

3. Your jewelry and other accessories should be discreet. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, where the lady code was simply what most undergraduate women wore most days, I heard a boy from a small Southern town say that a woman should never wear more than five pieces of jewelry. He gave as an example a watch, two earrings, a ring, and a bracelet. And I still remember an article in which Miss Manners (remember Miss Manners?) was asked where it was appropriate to wear an anklet (remember anklets?). She said: on the wrist, where it is called a bracelet. Coco Chanel popularized long ropes of fake pearls, but she was a fashion designer, and a lady is not fashionable. She has style, which is a different thing altogether. Fashion stands out: style is discreet and understated. At UVA, all the undergraduate women seemed to wear a single strand of real pearls, perhaps because they had all gotten one when they turned sixteen. I did myself, as my sixteenth birthday present . . .

4. This is a complicated one: you should look feminine but not sexual. Got that? This is one of the reasons the lady code is so often criticized: it’s nuanced and complicated. And it can be used to shame women: I still remember being at a funeral at a small town in the South and hearing two women talk about a third, who had worn a black suit that had obviously not been meant for a funeral. The fit was too tight, and it showed cleavage. It was sexy. I remember that it was worn with very high stiletto heels . . . On the other hand, one thing I find useful about the code, myself, is that when I dress according to it, my body becomes functionally invisible. I am seen as a teacher or lawyer, not as a potentially sexual woman. I am not hit on . . . So the code cuts both ways, and I suppose that’s why it’s survived. It is, in one sense, a means of social control. But in another, it’s a way that women have controlled how they are perceived. And by the way, skirt length? Between the lower calf and just above the knee. Anything shorter is perceived as sexual; anything longer is perceived as properly for evening.

5. You should have style, but not be fashionable, and your clothing should signal quality, even if you bought it at Goodwill. About half of my closet comes from Goodwill . . . This is a complicated one too, isn’t it? And men wonder why women have so many clothes! By fashionable, I mean whatever is “in” this season. I teach at a very fashionable university, and I still remember the semester every undergraduate woman wore culottes. It was the semester of the culottes. By next semester, the culottes were gone, and my fashionable undergraduates would not have been caught dead in them. Dressing stylishly means dressing in a way that is timeless, and by timeless I mean in a style that has lasted for at least ten years. (That’s now long timeless is in fashion.) A white blouse, slim jeans, ballet flats, and patterned scarf would have been as appropriate on Audrey Hepburn as they are now. Another of Hercules Poirot’s wonderful statements is that whatever else she may look like, a lady will wear good quality shoes. (He solves a case because a woman pretending to be Lady Somebody is wearing cheap shoes. I kid you not.) This, by the way, is part of the reason jewelry should be discreet: because unless you are the Queen of England or Elizabeth Taylor, large jewelry inevitably looks fake, even when it’s not. Small jewelry looks real, even when it’s not. And quality is often tied to the idea of authenticity: real linen, real leather, real pearls.

I think that’s enough for now, and do realize that this list is a work in progress. It is my attempt to figure out how this language of clothes works, how we perceive dress. There are all sorts of codes — for different disciplines, for example, so that a female scientist will be expected to dress a particular way, which is different from a female elementary school teacher, and different from a female lawyer. But the lady code is a fairly broad, underlying social code that has a lot to do with how women are judged in our culture, which is why I wanted to explore it in more detail. How do I dress? Mostly the way I’ve described above, although my clothes are a little more bohemian, because they’re allowed to be. I’m a writer and a professor. I get to be a little artsy. But I do have to be conscious about how I’m perceived, because I’m often “on”: for students, colleagues, readers.

There’s a lot more to say about the above. Dress codes can operate in very different ways depending on race, social class, and other factors, and those are certainly worth exploring, although I haven’t said anything about them here. And there are people who can afford to ignore dress codes altogether. They tend to be the wealthy, who don’t need to work, or people who work in ways that give them a great deal of independence in defining their own looks, although they often have codes of their own. If you are a tattoo artist, you’d better have tattoos, and they’d better be good ones. Very few of us exist outside of these codes altogether, just as very few of us exist outside language. They are ways we communicate, sometimes deliberately, sometimes inadvertently. Which is part of what makes them so fascinating . . .

(And if you want to know whether something you’re planning on wearing is “ladylike”? Ask yourself if Audrey Hepburn would wear it. I think that’s a pretty reliable test . . .)

March 1, 2014

Feeling Alive

When I first read this quotation from Joseph Campbell, I thought he must be wrong:

“I don’t believe people are looking for the meaning of life as much as they are for the experience of being alive.”

Many years ago, I had read Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which he says that what we need in life, most of all, is a sense of its meaning, of it being meaningful. And I believed him. I still do, but I think what Campbell says is true as well, in an even more fundamental and primary way.

We search for life’s meaning as intellectual beings, who reflect on our own state. But reflection is secondary: it’s us looking at our own lives, almost as though we stood outside them, and trying to locate a meaning in them. We do that in particular if we have suffered greatly, as Frankl (a concentration camp survivor) had. Finding meaning helps us — to deal with life’s intensity, its unpredictability, even if we have not suffered like Frankl.

But before we are intellectual beings, we are sensual beings, who experience the world by sensing, feeling. And before we look for meaning, we look for the experience of being alive, of feeling the intensity and unpredictability of life. We seek to participate in life itself.

We all want to feel alive.

Why am I making this point? Because it occurred to me, the other day, that we will do almost anything to feel fully alive, even if it hurts us in the process. It doesn’t have to hurt us: the need to feel alive makes us climb mountains, write books. It can result in exploration and adventure and art. So it’s a wonderful thing, a valuable thing. An intensely human thing. But like anything human, it can also cause harm. Recently, I read an article by a drug addict in which he described the need for a high as the need to feel fully and intensely alive — something he could not find in his ordinary life, even though he is a famous performer. It led me to wonder if many of our destructive behaviors could be caused by that perfectly natural need, and our inability to fulfill it in any other way. I don’t have many destructive habits: perhaps my tendency to overwork is the worse of them. That’s a behavior the world rewards, although it can be quite bad for me personally. It means that I sometimes collapse from tiredness, or miss out on aspects of life that could be rewarding. I don’t remember when I last kept up with a television show. But the work I do, both teaching and writing, makes me feel intensely alive, so it’s hard to rest. And I remember that when I was younger and did particularly stupid things (anything involving alcohol and dancing on tables, for instance), it was usually because I needed to feel alive, to feel a certain intensity that’s much easier for me to experience now, when I have more control over my own life. And when I have art.

I think art is probably the safest way to feel fully alive.

Experiencing art, by going to a concert or museum, makes us feel more intensely. But the true intensity comes from creating art. Even sitting here, writing this blog post, putting the words together while listening to Bach (which is what I’m doing), has a certain intensity to it. And then what I write will go out into the world, and you will either like it or not, find it relevant to you or not. There’s a risk in that, and the risk is fundamental to the intensity of the experience. We can’t feel fully alive without taking risks. That’s why climbing a mountain and writing a book will make us feel alive — they are different kinds of risks, but to both of them, we bring the totality of ourselves. We have to commit ourselves to the task. And that’s another component of feeling alive.

An idea is developing as I write this, about what it takes to feel fully alive. You commit yourself to something risky, something that feels greater than yourself. Like moving to Tokyo. (A friend of mine is currently living in Tokyo for several months, and I love to see the pictures she posts on social media. It allows me to participate in her adventures vicariously. But it would make me feel envious if I did not know that in June, I will be abroad myself, in Budapest for a month.) Like learning to play Bach on the cello. Something with a real possibility of failure. And then you do it, and see what happens. Perhaps we all need suspense in our lives, not just in novels . . . To feel fully alive, we need to feel as though we could fail. Isn’t that ironic? Because at the same time, we hate to fail, don’t we? We hate to fall, to make mistakes. And yet, so many of us, if our lives are too safe, if they are too ordinary, will long for something to take us out of ordinary safety. We will say, let’s move to Tokyo.

We need risk and the possibility of failure in order to feel alive, and we need to find meaning in life in order to deal with risk and failure. Imagine Campbell and Frankl dancing a waltz . . .

I write this in part because there’s been a sort of backlash recently against the Campbellian message that we should all follow our bliss. There are people who say, following your bliss can lead to failure. It can be more sensible to lead a good, ordinary life. And it can. But if I weren’t following my particular bliss? If I weren’t risking failure? I’m not sure what I would do. No, I do know, because I remember being a lawyer, and what that was like. I had made the safe decision, the sensible decision from a financial standpoint. And I felt dead. I went to the same office every day, I did work for clients that in many cases I did not respect. And I was not healthy, physically or mentally. I can understand how, under those circumstances, someone would turn to destructive behaviors, simply to feel alive. I think what Campbell means by following your bliss is this: do what makes you feel fully alive.

And if you’re not sure what that is, if you’re still searching for something to bring you to life? I recommend art.

(These are the flowers I bought this week. Today, the branches are sprouting leaves. They are coming to life . . . You can also feel alive by experiencing ordinary life more intensely — by going out into a forest and feeling the trees around you, by walking down the streets of a great city and feeling it surging with life. That comes with its own kind of risk, which is riskier in some ways than moving to Tokyo, because it involves an engagement with and descent into the self. But more on that another day.)

February 22, 2014

Being a Soulmate

I’ve been thinking about the idea of a soulmate, because I’ve seen friends who are in relationships, and friends who are not in relationships but searching for romantic partners. The idea of a soulmate is central to our idea of relationships now, isn’t it? That’s what we are all searching for, a soul mate, a partner who shares something with us that is of the soul, that goes to the core of who we are. I’ve seen friends who are convinced they are with their soulmates, and friends who are trying to find theirs . . .

And it seems to me that we’re thinking about the concept in the wrong way.

The goal shouldn’t be to find a soulmate. It should be to actually be a soulmate. And I think a soulmate is not necessarily a romantic partner. It’s anyone with whom you have a deep connection, and it can be a parent, a friend, a child . . . We need soulmates, and we need lots of them, but the best way to have soulmates is to be a soulmate, meaning to be the sort of person who is a soulmate to other people. Which is something you can practice.

So what does it mean to be a soulmate? Think about what we want from our romantic partners: we want to be understood, and then we want to be loved for who we are. A soulmate makes us less lonely, and there is a sense in which we are all alone: we all perceive the world from within our individual bodies, with our individual consciousness. As soon as you close your eyes, you are alone in the dark. A soulmate offers connection, and support, and understanding. A soulmate offers love. But it’s love that comes from and reflects that deep connection: the soulmate loves you for and because of who you are. This is why I say a soulmate can be a parent, friend, a child. A soulmate can even be an animal. (Those who have deeply loved and been understood by a cat or dog will know what I mean.)

One way to make your life rich and wonderful is to have soul mates, and lots of them. But by lots, I don’t mean hundreds, because I think that’s impossible. You can’t connect that deeply with so many people. If you have two, or five, or ten, you’re doing well. What you want to do, of course, is be a good soulmate to them, to give them the love and understanding, the support, that you want yourself. (I should say, here, that being a soulmate is a reciprocal relationship. If you’re not getting that love and understanding back, it’s not a soulmate relationship, but something else. Obviously, what you get back will depend on the person in the relationship, and will change over time: a relationship with a child is not like one with a friend or parent. But the bond will be reciprocal.)

To have soulmates, you need to be a soulmate, and that takes practice. None of us is a soulmate naturally: we need to learn how. The best way to learn, the way you can always practice, is to be a soulmate to the one person you should always treat with love and understanding: yourself. You need to be your own soulmate.

There are several reasons you should be your own soulmate. First, because you’re handy: you will always be there to practice on. Second, because you need love and understanding and support, right? And there will be times when other people can’t give you those things, so you should be able to give them to yourself. And finally, because in our culture, we put such emphasis on finding a soulmate, by which we mean a romantic partner, and then we expect that partner to be our only soulmate, to be the person who gives us all the support and connection we need. Which is way too much of a burden to put on a romantic relationship, or on one person in general. We expect a partner to complete us, without realizing that we need to complete ourselves, so we can bring a complete person to the relationship. And, indeed, to all our relationships.

So, how do you go about being your own soulmate? Well, you can start by making a list of all the things you want from a soulmate. And then, systematically, figuring out how to supply those things for yourself. I was thinking about the things we typically want from relationships: things like love, and a home, and security. Adventure. The impetus to grow and become more of what we should be, more of ourselves. Those are the things we need to provide for ourselves. It’s only when we can provide them for ourselves that we can truly share them with other people: it’s only when you know how to go off on adventures that you can invite others on them. You can’t wait for other people to be the source of your adventures, or your security, or personal growth. If you can’t create a home for yourself, it’s very difficult to have one with another person.

Because here’s the thing: if you don’t love yourself enough, no one else is going to be able to love you enough to make up for that absence. No one else can fill up that particular abyss.

It’s dangerous to approach relationships, particularly romantic relationships, with that sense of need, to expect a romantic partner to supply what you can’t supply yourself. The danger is, in part, that you will get into or stay in a relationship that is unhealthy, simply because a relationship of any sort is better than no relationship at all. But an unhappy relationship, potentially even an abusive relationships, is worse.

On the other hand, a relationship in which two people can be their own soulmates, and also soulmates for each other: that’s the ideal, isn’t it? That’s when you can be a parent without expecting your child to fulfill your dreams, because you’ve fulfilled them yourself. Be a friend without expecting your friends to resemble you or agree with all your opinions, because why should they? Loving them as they are. And that’s when you can be in a romantic relationship without expecting your partner to supply what you lack, because you can do that yourself. So you can truly be partners, together because you want to be. The bonus of being in a romantic relationship is that you can practice being a soulmate to yourself and your partner at the same time. But you should never neglect being a soulmate to yourself.

This is a photograph of my paperwhites in full bloom. Outside, the ground is still covered with snow, but inside, I have created my own spring . . .

(One word of caution. By saying that you should practice being a soulmate, I am not at all implying that you should be or stay in relationships that are one-sided, in which you are supplying all the soulmate-ness. One reason to be your own soulmate is so you won’t get into those sorts of relationships. Soulmate relationships are always reciprocal. If you are good at being a soulmate, you will find that people want to be your soulmate, will actively seek you out for that purpose. And some of them will be soulmate material, but others won’t — they will be coming to you out of their own need for affirmation, their own sense of lack. But you won’t be able to help them: you can’t supply for other people what they can’t supply for themselves. They will also need to learn how to be their own soulmates. That’s the work we all need to do, for and by ourselves . . .)

February 16, 2014

Your Fairy Tale Name

As you may know, I teach a class on fairy tales. In my class recently, we were talking about names in fairy tales. Very few characters in fairy tales have ordinary names: they are almost never Ann or Michael. Their names mean something: Snow White is as white as snow, Cinderella has to sleep among the cinders. Blue Beard is frightening because of his blue beard, which is as unnatural as his propensity to kill his wives. Puss in Boots is distinguished by his footwear. Their names are attributes. Or their names can be nonsense words that are also codes, that don’t mean anything but also mean your freedom: Rumplestiltskin, for example. Many fairy tale characters don’t even have names: they are the Prince or the Miller’s Daughter.

If I were just a professor, I would go on about the meaning and function of fairy tale names. But I’m also a writer, so I’ve created a way for you (yes, you) to find your own fairy tale name. What would you be named if you were in a fairy tale? Take this short quiz to find out:

(Illustration for “Cinderella” by Margaret Evans Price.)

1. Are you a man, a woman, or an animal? If you are a man, go to question 2. If you are a woman, go to question 8. If you are an animal, go to question 15.

2. If you are a man, are you good, evil, or morally ambiguous? If you are good, go to question 3. If you are evil, go to question 4. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 7.

3. If you are a good man, your name is “Prince” + [your best character trait]. Ex. Prince Organized.

4. If you are an evil man, do you have magical powers? If you do, go to question 5. If you don’t, go to question 6.

5. If you are an evil, magical man, your name is “The Wizard of” [where you live]. Ex. The Wizard of Portland.

6. If you are an evil man but not magical, your name is [your name] + “the Ogre” or “the Troll” (your choice). Ex. Sidney the Ogre.

7. If you are a morally ambiguous man, take your name and scramble the letters to form a nonsense word. Ex. Nathajon. (Try not to steal any children. It never pays.)

8. Are you a good, evil, or morally ambiguous woman? If you are good, go to question 9. If you are evil, go to question 13. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 14. If you are descended from fairies, go directly to question 22.

9. If you are a good woman, do you define yourself by your best character trait, your best physical feature, or the challenges you have overcome? If by your best character trait, go to question 10. If by your best physical feature, go to question 11. If by your challenges, go to question 12.

10. If you are a good woman and define yourself by your best character trait, your name is [that character trait]. Ex. Patience. (Be prepared to demonstrate that character trait throughout the tale.)

11. If you are a good woman and define yourself by your best physical attribute, your name is [the best thing about that attribute] + [that attribute]. Ex. Sparkling Eyes.

12. If you are a good woman and define yourself by the challenges you have overcome, your name is [your most difficult challenge] – any final vowel + “ella.” Ex. Insomniella. Alternatively, if you have a distinctive article of clothing, you may choose to identify yourself by that article. Ex. Blue Wool Coat.

13. If you are an evil woman, your name is “The Wicked” + [your job]. Ex. The Wicked Accountant. (Watch out for red hot iron shoes.)

14. If you are a morally ambiguous woman, your name is [your favorite natural phenomenon] + [the color of that phenomenon]. Ex. Sleet Gray.

15. If you are an animal, are you really an animal, or are you enchanted? If you are really an animal, go to question 16. If you’re actually enchanted, go to question 19.

16. If you are really an animal, are you good or morally ambiguous? If you are good, go to question 17. If you are morally ambiguous, go to question 18.

17. If you are a good animal, your name is “Good” + [your name]. Ex. Good Jennifer. (You will probably have your head chopped off by the end of the story, but everyone else will live happily ever after.)

18. If you are a morally ambiguous animal, your name is [your favorite animal] + “in” + [your favorite article of clothing]. Ex. Kangaroo in Pajamas.

19. If you are enchanted, are you an enchanted man or woman? If you are an enchanted man, go to question 20. If you are an enchanted woman, go to question 21.

20. If you are an enchanted man, your name is [your name] + “my” + [you favorite animal]. Ex. Andrew my Aardvark. (You will spend the tale trying to find a woman to disenchant you.) Alternatively, you could choose to be called “The” + [your favorite animal] + “Prince.” Ex. The Llama Prince.

21. If you are an enchanted woman, your name is [your name] – any final vowels + “ette” (if good) or “ile” (if evil). Ex. Amandette, Amandile. (By the end of the tale, you will have caused the Prince’s death. These things happen . . .)

22. If you are descended from fairies, your name is [color of your favorite flower] + [name of that flower]. Ex. White Lily.

Now that you have your fairy tale name, you’re ready to take your part in a fairy tale. Good luck! I hope you survive . . .

(Illustration for “The Frog Prince” by Mabel Lucie Attwell.)