Theodora Goss's Blog, page 17

March 7, 2015

Teaching Writing

Recently, I read an article called “Things I Can Say About MFA Writing Programs Now That I No Longer Teach in One” by Ryan Boudinot that has been making its way around social media, prompting a lot of controversy. It made me think about my own teaching of writing, and what I’ve learned over the years as a writing teacher. You see, I’ve been teaching writing for more than ten years now, in various ways: I’ve taught both academic and creative writing, to high school students, college students, and graduate MFA students. I’ve taught writing to students who are still learning English. I’ve taught writing to students who have gone on to publish professionally. If I may say so myself, I have a lot of experience in this field.

The lessons I’ve taken away about the teaching of writing are very different than those learned by Boudinot, and I thought I would list them here. They come both from teaching writing and from having been taught writing, in college creative writing classes as well as the professional workshops I attended in order to learn writing myself. Here are the things I’ve learned.

1. You are a terrible judge of who has talent or potential.

I’ve seen it several times: a teacher will “anoint” a particular student: the one with talent, the one who will succeed. The teacher will usually be a celebrated writer, who will assume that he or she can judge who is talented, who has potential. The problem with this assumption is that in real life, it doesn’t work. Over and over again, I’ve seen it fail. In college, when I was taking poetry classes, I was not the anointed one. No, the anointed one was another girl, who wrote weird, dark, innovative poetry. I’ll call her Jane. One day, I was heading to see my poetry professor, who was as famous as poets get nowadays. I stopped outside his office door, which was open a crack, when I realized he was talking to someone else. It was another of the famous poets in the department, and they were discussing who was going to get into the top-level poetry class, with the most famous poet of them all. I heard Jane mentioned — of course she was going to get in. My professor said the class was for students “like Jane.” I walked away before I could hear more, embarrassed that I had overheard a conversation not meant for me. And I never applied for that class, because it was clear to me, in a number of different ways, that I wasn’t one of the anointed. Years later, I wondered what had happened to Jane. I figured she would be a writer of some sort? Her name was distinctive enough that when I googled her, I found her right away. She had become a mother, a community activist — a lovely woman with a lovely life. But not a writer.

Much later, in a writing workshop, I was one of the anointed. There were two of us: the writer in residence, a famous writer, told us that we were the two students who would succeed. It meant a lot to me, to be labeled in that way. It gave me confidence I had not had before. The next summer, I started publishing. The other student? Is no longer writing, as far as I know.

After having taught more than a thousand students (at least a hundred a year), I no longer believe in talent. What I believe in are talents. Different students have different talents, are good at different things. My job as a teacher is to see those talents, even when the student can’t see them himself or herself. To identify them, encourage them, help the student build on them.

2. It’s important to learn writing, both to communicate with others and for its own sake.

We all need to learn to write well. Writing is one of the most important tools we have, as human beings. It allows us to store information outside our heads and to communicate with others. I sometimes have undergraduate business students tell me, in frustration, that they don’t understand why they are required to take two semesters of writing. I tell them, as gently as I can, that I used to be a corporate lawyer, and as business people, their entire lives will be writing. But apart from being enormously useful, writing is important to us as human beings — it allows us to reflect on who we are, where we’re going. Many of my students tell me about keeping journals, about how that personal writing has helped them.

It’s fashionable, nowadays, to question the value of an MFA. People say it’s a bad return on investment, that most MFA students won’t succeed as writers, won’t make back the money they spent on graduate school. But most of my MFA students aren’t there to make a specific amount of money, or even to start an academic career, although many of them hope to teach eventually. They’re there because they want to spend time writing, and spend time with other people who are writing. They want to become better writers. They go for the love of writing itself. Yes, of course you can learn to write in cheaper ways — I went to both Odyssey and Clarion, and of course I read a lot. But sometimes I wish I had gone to an MFA program. I see that my own students are getting things out of the program I never got, and I envy them.

If you mock students for pursuing an MFA on financial grounds, think about what you’re doing. Yes, finances are important. I’m realistic, I went to graduate school. I still buy clothes at Goodwill out of frugality and habit, and if there’s free food, I’m going to eat it. But I chose to give up a legal career in which I was earning $100,000 a year for a $10,000 a year graduate school stipend, because there are more important things in this world than financial considerations. And yes, I still have student loans. But I’m a better writer, and the person I wanted to be. Also, not sitting in an office calculating the number of billable hours until my statistically probably death . . . (Yes, I did that.)

3. Writing can be both taught and learned. Anyone can learn to write better.

Of course writing can be taught. Can you imagine what it would sound like, if we spoke about other arts the way we do about writing?

“Ballet can’t be taught. You either know how to do it or you don’t.” “The cello can’t be taught. Only people with innate talent can learn to play the cello well.” “Acting can’t be taught. You just need to watch a bunch of actors and then do it yourself.” Seriously?

Anything can be taught. It can be taught well or badly. And anything can be learned, if the student is a willing and attentive learner. Writing is a skill, not some sort of mystical holy spirit that descends on you as you’re sitting at your desk. Creative writing, in particular, is a craft and an art. The craft part of it can be taught just as oil painting can be taught: the painter in oils learns certain techniques, and so does the writer. This is how to create a character who comes alive. This is how to write a scene that makes your reader see a particular place, feel a particular emotion. The art of it is individual, but even that can be enhanced and cultivated. You can teach a writer to become greater than himself or herself: to observe the world more acutely, to spend time with music and art in order to learn more about writing. To hear the sound of his or her own voice, find his or her own material. All of that, a good teacher can help bring out.

4. Real life interferes with writing. Deal with it.

If you’re not writing consistently, you must not be serious about it? Oh, come on! I’ve had students with family obligations, mental or physical illnesses. If you don’t think life presents you with situations that are more important than writing, you haven’t been paying attention. I’ve had times in my own life when I could not write consistently, because I had a child to take care of, a PhD thesis to finish. Unless we are already rich from writing, we all have to fit it in somehow, around our work, our family lives. Most of the professional writers I know are a little ruthless about fitting in writing, and feel guilty about how it impacts other parts of their lives. But they also know if they don’t do it, they won’t quite be who they are, who they need to be. That’s what normal looks like, for a writer. You’re pulled in different directions.

As soon as a writer can, he or she goes back to writing, because as I said above, without it the writer does not feel quite whole. It feels as though a hole is opening up in your chest, and getting larger. Also, I don’t know about you, but I get very cranky and unpleasant to be around.

5. The world is filled with stories, and needs stories. Of all kinds.

When I tell my college students to write stories, they astonish me with what they produce. No, most of their stories would not be publishable (although some of them are of almost publishable quality), but there is so much in them — wisdom, feeling, personality. We all have stories to tell, and helping students figure out how to tell their stories better is an important and worthwhile thing to do. There are times when I’m very tired, and wish I could devote more time to my own writing. But I always believe that what I’m doing, in teaching people to write more clearly and effectively, to tell their own stories, is worthwhile. It’s worthwhile to see a student who is still learning English develop a better understanding of sentence structure. It’s worthwhile seeing a graduate student gain his or her own voice and start publishing stories. I believe we’re put on earth to do important, meaningful work. Not to make a certain amount of money, not to gain a certain amount of fame. Certainly not to write snarky articles that gain us a lot of attention.

Writing is not a small club in which only the “best” are allowed. It’s not made up of James Joyce, Hemingway, and David Foster Wallace. We need books for children about Loraxes, and Big Red Dogs, and even potty training. We need trashy romance novels with pirates on the cover. We need cookbooks. We need Hemingway and Virginia Woolf and Agatha Christie and A.A. Milne. Some people need Billy Collins. I, personally, need Louisa May Alcott and Frank L. Baum and Lewis Carroll. Writers are often told to read, and what they are told to read is Important Writers. But if all we had was Important Literature, the world would be a dull place indeed. I don’t know about you, but while I recognize the genius of Anna Karenina, I’m not going to read it in the bathtub.

Personally? I try to write as well as I can. I try to be the best writer I can be, in the way I understand good writing. (Some Serious Writers bore me to tears. But then so do romance novels, although when I was a teenager, I read them as though they were mental candy.) I try to read, not always widely, but deeply. I try to live deeply as well, to experience the world around me so I can write about it. I try to learn from art, from music, from other people. And I learn from my students . . .

6. Good teachers learn more from their students than they teach.

This should be obvious. If you’re a good teacher, it’s because you were once a good student. And the best students can learn from anything, in any circumstances. They can learn from professors they barely understand. They can learn from abject failure.

I feel the same dread, looking at a large pile of papers to grade, as any teacher. But I also know that when I read my students’ writing, when I teach a class, I learn more than I teach. This is partly because to teach anything effectively, you need to know much more about it than you will ever mention in the classroom. In order to teach writing, I had to learn a lot more about writing than I had ever known before — a lot more theoretically and practically. I needed to actually know the comma rules. (A lot of professional writers don’t know the comma rules. Seriously.) I needed to read books on writing by John Gardner, Milan Kundera, Mario Vargas Llosa, Eudora Welty, Ursula Le Guin, Steven King, Dani Shapiro . . . But I also learn from editing the writing itself. I realized recently that from reading writing by non-native English speakers, I was learning different — vigorous, interesting, and non-intuitive — ways of constructing sentences.

7. Great writers are not necessarily great teachers. Teaching writing is itself a separate skill that can be cultivated.

Remember the famous poet I mentioned back at the beginning? His class discouraged me so much that I didn’t write poetry seriously for many years, and still have difficulty seeing myself as a poet. In retrospect, it wasn’t that he was a bad person or a bad poet. He was just a bad teacher. It was a lousy class. We sat around workshopping each other’s poems, which were bad. Because we were college students, and our poetry was bound to be pretty bad at that point. But we were never taught how to make it better, never taught that there were poetic techniques, never taught why modern poetry was written as it was. We were given no historical knowledge or critical apparatus at all.

Great writers can be lousy teachers. Teaching writing is itself a skill, which can be developed. You can learn how to help a student make a manuscript better, how to understand what a student is saying beneath what he or she seems to be saying. You can explain concepts clearly, edit helpfully. I’m a much better teacher now than I was ten years ago. And I look at the great writing teachers I know, like James Patrick Kelly and Elizabeth Hand: I learn about teaching from watching them teach.

Honestly, I think teachers (or former teachers) who are snarky about students are often in that mode because: (a) they have just finished grading a large pile of papers, in which case it’s temporary and understandable, or (b) they feel their own failures as a teacher acutely, and it’s only by blaming students that they can make that feeling — of inadequacy or sometimes shame — go away. It’s actually noble to feel your own inadequacy in that way. There are certainly times I have failed as a teacher — times I have been unhelpful or unclear, times a student was frustrated and it was my fault. What I can say for myself is that I try harder to do better. And I try, always, to give the student the benefit of the doubt. To believe in the student, as I wanted my teachers to believe in me.

In the end, to be a good writing teacher, you need to love teaching as well as writing. Teaching challenges you to reach outside yourself, to see a student as a fellow writer and human being. To see what is of value in writing that may be unclear, or by rote, or filled with proofreading errors. To say both “it’s not acceptable to hand in a manuscript you haven’t thoroughly proofread, so please revise and resubmit it” and “there is something of value in here, and let’s talk about what that is.” It challenges you as much as writing challenges you, on a deep level. Not everyone loves that challenge. I happen to, which is why I teach.

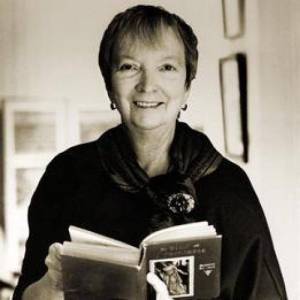

(This is me at my desk, preparing for a class . . .)

March 5, 2015

What Madeline Said

Recently, I came across some quotations from Madeline L’Engel, and they seemed to me so useful, and so essentially true, that I thought I would make a list of them here. I read in part to get myself through the difficulties of life, and I’m always grateful for a book that takes me away from them, and at the same time teaches me how to deal with them more effectively. Because life is difficult, isn’t it? If you think it isn’t, you’re very lucky . . . or haven’t been paying attention. That doesn’t mean a book has to be therapeutic. The fairy tales of Hans Christian Anderson have more to teach us, I think, than many self-help books.

I first read L’Engle as a child: A Wrinkle in Time, A Wind at the Door, and A Swiftly Tilting Planet. Those books were infinitely comforting to me. They said, the universe is bigger than you know. Evil exists, but you can fight it. You have allies, the whole of creation is your ally.

So if you’re in need of some wisdom, as I am right now, here are a few quotations from L’Engle. May they help.

“You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.”

“A self is not something static, tied up in a pretty parcel and handed to the child, finished and complete. A self is always becoming.”

“When we were children, we used to think that when we were grown-up we would no longer be vulnerable. But to grow up is to accept vulnerability . . . To be alive is to be vulnerable.”

“Some things have to be believed to be seen.”

“Our truest response to the irrationality of the world is to paint or sing or write, for only in such response do we find truth.”

“We are all strangers in a strange land, longing for home, but not quite knowing what or where home is. We glimpse it sometimes in our dreams, or as we turn a corner, and suddenly there is a strange, sweet familiarity that vanishes almost as soon as it comes.”

“Stories make us more alive, more human, more courageous, more loving.”

“Inspiration usually comes during work rather than before it.”

“But unless we are creators we are not fully alive. What do I mean by creators? Not only artists, whose acts of creation are the obvious ones of working with paint of clay or words. Creativity is a way of living life, no matter our vocation or how we earn our living. Creativity is not limited to the arts, or having some kind of important career.”

“We don’t want to feel less when we have finished a book; we want to feel that new possibilities of being have been opened to us. We don’t want to close a book with a sense that life is totally unfair and that there is no light in the darkness; we want to feel that we have been given illumination.”

“I think that all artists, regardless of degree of talent, are a painful, paradoxical combination of certainty and uncertainty, of arrogance and humility, constantly in need of reassurance, and yet with a stubborn streak of faith in their own validity no matter what.”

“It’s a good thing to have all the props pulled out from under us occasionally. It gives us some sense of what is rock under our feet, and what is sand.”

“If it can be verified, we don’t need faith . . . Faith is for that which lies on the other side of reason. Faith is what makes life bearable, with all its tragedies and ambiguities and sudden, startling joys.”

“That’s the way things come clear. All of a sudden. And then you realize how obvious they’ve been all along.”

“Only a fool is not afraid.”

“I do not think that I will ever reach a stage when I will say, ‘This is what I believe. Finished.’ What I believe is alive . . . and open to growth.”

“Stories are like children. They grow in their own way.”

“On the other side of pain, there is still love.”

February 28, 2015

Stonecoast: Wizard of Earthsea

A couple of posts ago, I wrote about the workshop I led at Stonecoast last winter, on fantasy writing. I mentioned that I had given the students a series of quotations, and we had discussed them as examples of various writing issues and techniques. This is one of the quotations I used to talk about character: the beginning of A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin. But there’s so much more going on here than the establishment of character! I have a list of writers that I learned from myself, as a writer. Le Guin is one of the most important of them. She’s one of the reasons I try to write clearly, fluidly. I think lyricism is based on clarity of expression. She’s also one of the reasons I try to write about ideas, as much as I try to write about characters. She’s one of my models for what a courageous writer looks like.

So what is she doing here, in this opening?

“The island of Gont, a single mountain that lifts its peak a mile above the storm-racked Northeast Sea, is a land famous for wizards. From the towns on its high valleys and the ports on its dark narrow bays many a Gontishman has gone forth to serve the Lords of the Archipelago in their cities as wizard or mage, or, looking for adventure, to wander working magic from isle to isle of all Earthsea. Of these some say the greatest, and surely the greatest voyager, was the man called Sparrowhawk, who in his day became both dragonlord and Archmage. His life is told of in the Deed of Ged and in many songs, but this is a tale of the time before his fame, before the songs were made.

“He was born in a lonely village called Ten Alders, high on the mountain at the head of the Northward Vale. Below the village the pastures and plowlands of the Vale slope downward level below level towards the sea, and other towns lie on the bends of the River Ar; above the village only forest rises ridge behind ridge to the stone and snow of the heights.

“The name he bore as a child, Duny, was given to him by his mother, and that and his life were all she could give him, for she died before he was a year old. His father, the bronze-smith of the village, was a grim unspeaking man, and since Duny’s six brothers were older than he by many years and went one by one from home to farm the land or sail the sea or work as smith in other towns of the Northward Vale, there was no one to bring the child up in tenderness. He grew wild, a thriving weed, a tall, quick boy, loud and proud and full of temper. With the few other children of the village he herded goats on the steep meadows above the river-springs; and when he was strong enough to push and pull the long bellows-sleeves, his father made him work as a smith’s boy, at a high cost in blows and whippings.” — Ursula Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea

First, notice that we are on the move: just as in the beginning of The Hobbit (which I discussed two blog posts ago), we as the readers are in motion. This time, we begin above the island itself, looking at it from what is often called a bird’s eye view. That’s a particularly accurate description here, because we swoop down over the island, from its high peak toward the towns on its slopes, then down still further, to its ports and bays. We fly up again toward the village of Ten Alders, and then we are with the boy who will become Ged, watching him herd goats in the meadows. It’s as though we’ve landed in the branch of a tree, and are watching this intractable boy. At the beginning of Le Guin’s book, we are the Sparrowhawk. We move as the hawk moves.

This happens thematically as well. The opening moves from a grander, larger view toward a smaller, more intimate one: Sparrowhawk to Ged to Duny. Dragonlord to archmage to goat herd. The Deed of Ged to this story, of the days before his fame. But as it moves downward and inward, it has already told us that it will move upward and outward: the boy we are going to study and spend time with will become something we can scarcely comprehend: archmage and dragonlord. We will start in Ten Alders, but the journey will eventually take us from isle to isle of all Earthsea.

I’ve become convinced that one way to introduce tension into a scene, any scene, is through opposition: show the reader opposites. This entire scene is structured by the oppositions between boy and man, village and world, present and future. Even the opposition between poetry and prose, because somewhere out there is the Deed of Ged, but this is not that story.

It’s a brilliant opening.

A Wizard of Earthsea tells a story that sounds, on the surface, a bit like Harry Potter: boy goes to study magic at a school for wizards. And yet it’s also about as unlike Harry Potter is it could be. It’s less popular, although I suspect it will become more of a classic. I think it’s less popular because although Ged also has to defeat an evil that he first meets at his magical school, in A Wizard of Earthsea that evil is himself. That’s not as much fun as defeating a villain like Voldemort, is it? Harry Potter is more fun. But A Wizard of Earthsea is deeper. It’s less wish-fulfillment, more a deep lesson about the self, a lesson we eventually all have to learn. J.K. Rowling is a very good writer. Ursula Le Guin is something more than that.

But here I’m talking specifically about her writing technique. This is an opening every writer should study, for the way it moves, the way it has us enter the story. Like the opening of The Hobbit, it’s genius . . .

(This is the version of A Wizard of Earthsea that I read as a child, and still own. Predictably, I had the boxed set of all three books.)

February 19, 2015

How I Do It

Sometimes, I don’t do it very well. But I keep doing it . . .

This blog is inspired by two articles I read lately about female writers: “The Price I Pay to Write” by Laura Bogart, which was itself a response to “‘Sponsored’ by My Husband: Why It’s a Problem That Writers Never Talk About Where Their Money Comes From” by Ann Bauer. Bauer wrote about how getting married and being supported financially by her husband had given her the time she needed to write. Bogart wrote in response about how she struggles without that sort of support — what writing is like when no one is sponsoring you.

Since then, I’ve seen several writers describe how they, individually, make it work . . . and I thought I would add my voice to the mix. I was particularly prompted by a friend, an editor, who posted on Facebook, “I’m pretty sure that people who write publishable books and also have full-time jobs are magical creatures, like unicorns.” Which makes me a unicorn, I suppose . . .

Because I have a full-time job, and a part-time job, and I write. I can’t afford to do it any other way.

Here’s how I do it. My full-time job is teaching undergraduate writing at Boston University. I teach a 3/3 schedule, which means that each semester I teach three classes. I’m in class nine hours a week, and then on top of that I prepare for class, meet with students, and comment on their papers. In a typical week, I’ll spend more than forty hours on my full-time job. And I’ll spend extra time making sure that I’m up on what I’m teaching, meaning that I’ve read the latest books and articles on the topic I’m teaching. After all, I’m supposed to be a scholar, teaching my students to think like scholars, or at least take the same time and care as scholars would in their research. Right now I’m teaching fairy tales, so all of that research is pure pleasure for me . . . I love reading fairy tale scholarship and keeping up with the popcultural discourse on fairy tales. I don’t always love commenting on grammar errors, but that’s part of my job — and honestly, I’ve learned a lot from doing just that. It’s not always the most comfortable job in the world — yesterday I walked several miles back and forth from classes in the cold and snow, because the trolley system isn’t working after our record snowfalls. But it gives me a steady income, health insurance, and most importantly the freedom to teach topics I love. I get to structure my own classes and much, although not all, of my own workday. I’m very lucky to have a job I love doing.

Or rather, two jobs I love doing. My second job is teaching graduate creative writing students in the Stonecoast MFA Program. Each summer and winter I go teach a residency at Stonecoast, and in the spring and fall, I mentor three to four students. I read and critique their writing, and we talk about writing issues. It’s more challenging, in terms of the writing issues involved, than teaching undergraduates: we’re focused not on the mechanics of writing, but on the art. On creating characters who come alive, a setting that you’re convinced is real. On moving a story at the right pace. On the practical side, these two jobs give me what I think of as a solidly middle-class income. Not as much as I earned my first year out of law school, twenty years ago. But as much as an experienced legal secretary would be earning. Enough for necessities and some luxuries. (By luxuries I mainly mean books.)

I have two extraordinary expenses that I can’t do much about. First, I live in Boston, which is one of the most expensive cities in the country. People from places like Asheville, North Carolina grow pale when I mention my rent. It takes up fully a third of my income, for a comfortable but certainly not large one-bedroom apartment. Second, I have a ten-year-old daughter, for whom I share responsibility. I want to make sure that she has what she needs, like clothes for a growing girl (the speed with which she destroys jeans is truly astonishing), and also some luxuries, like cello lessons and trips to the museum.

I consider myself very lucky: I can pay my bills, which include student loan payments from when I was in graduate school and pregnant with my daughter, so I couldn’t teach. I can afford some things that make life more comfortable and pleasant, like good chocolate. But I try to reduce my expenses as much as possible. I don’t own a car. I buy most of my clothes at either The Gap or Goodwill. I almost never go out to eat, and when I travel it’s usually because I need to be somewhere for a conference or research. It’s almost always on business.

So where does writing fit into all this? Well honestly, it fits into the nooks and crannies. It fits in whenever I can fit it in. I suppose it fits in where other people would be watching television? Or knitting, I don’t know. I try to fit it in wherever I can. Which means that I’m less productive than many of my friends who are making a living from writing. They simply have a lot more time to write. That’s the downside — the upside is that I’m not sure it makes a difference in terms of quality. If I weren’t working, I would probably be writing more — but I’m not sure I would be writing better. When I think about the writers I love, they didn’t write a lot, or at least not as much as it would have taken to support themselves simply by writing: Jane Austen, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Isak Dinesen, Angela Carter. But they wrote supremely well. Some of them were lucky enough to be supported in various ways, but those were other times. I’m not sure being supported is a particularly good idea now, and I suspect that Austen, if she were alive today, would have a job. She would be supporting herself.

Who knows how it will work out for me. I hope the novel I’ve written is good, I hope I can write the sequel. I hope there will be other novels, short stories, essays, poems. There are times I get tired, times I get dispirited. But I think we all do, no matter our circumstances. For the most part, I love what I do.

So how do I do it? I just work very, very hard. Perhaps someday it will be easier — I’d like it to be. I’d like more time to write. But in the meantime, I fit writing in whenever and wherever I can. I suspect many of us do.

(This was me at Boskone last weekend, being the writer rather than the teacher or academic . . .)

February 4, 2015

Stonecoast: The Hobbit

I want to write a couple more posts about my experience at the Stonecoast residency this winter. As you know if you read my last post, Stonecoast is a low-residency MFA Program in which I teach, which means that I go up to Maine for residencies in the winter and summer, and then mentor students during the spring and fall semesters. This past residency, I led an elective workshop on writing fantasy. Most of the workshop was spent critiquing the stories students had submitted. But we also talked about the particular challenges of writing fantasy. The first day we talked about setting, then characters, then plot, then style. I thought I would talk for a bit here about creating setting in fantasy fiction, because it presents problems that realistic writers don’t have to deal with.

Basically, when you’re writing fantasy, you may be setting your story in a world that doesn’t exist. It can be much easier for a realistic writer, because he or she will have points of reference for the reader. “I walked through Central Park” immediately conveys an image to most readers (who have been in Central Park, or more likely seen it in movies or on television). “I walked through the gardens of the temple of Ashera” tells the reader exactly nothing. It conveys absolutely no visual image, except perhaps a green horizontal thing beside a gray vertical thing. So as a fantasy writer, you often have to work harder.

The day we talked about setting, I brought in a quotation for us to discuss. You’ll recognize it at once:

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that meant comfort.

“It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with paneled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots and lots of pegs for hats and coats–the hobbit was fond of visitors. The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill — The Hill, as all the people for many miles round called it — and many little round doors opened out of it, first on one side and then on another. No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had a whole room devoted to clothes), kitchens, dining-rooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms of all were all on the left-hand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows, looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river.

“This hobbit was a very well-to-do hobbit, and his name was Baggins. The Bagginses have lived in the neighborhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but also because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him. This is a story of how one Baggins had an adventure, and found himself doing and saying things altogether unexpected. He may have lost the neighbors’ respect, but he gained — well, you will see whether he gained anything in the end.” — J.R.R. Tokien, The Hobbit

That’s Tolkien at his most brilliant, getting you right into the story by describing where we are, by giving us setting. But notice how cleverly he’s doing it, and what risks he takes. In a hole in the ground lived . . . what? A hobbit. We have no idea what a hobbit is, so he has to tell us, not by telling us, but by describing that hole in the ground. He’s not actually going to tell us what a hobbit is until later. The reference to a hobbit can make us feel displaced, so he’s going to place us: we’re in a hole. He starts by doing something I was taught not to do in writing workshops: telling us what isn’t there, what that hole is not like. It’s not dirty or wet or dry or sandy. No, it’s comfortable. And then he describes it.

One thing I’ve come to understand from teaching writing is that to work, writing needs tension: you need to feel things pulling against each other. Tolkien starts that pulling right at the beginning: the tension between our assumptions and the truth. We think a hobbit hole might be nasty, but it’s not. Look . . .

And then Tolkien takes us on a tour. One continual problem with how writers describe setting is that they stop, and then they describe. We are still. Tolkien describes the hobbit hole, but notice that we are on the move: we enter through the door, move down the hall, hang up our hats. (Just as the dwarves will, later in the chapter. We are the hobbit’s guest before they are. We are the storyteller’s guest, and only at the end do we realize that in a sense, the storyteller was the hobbit all along.) Then we keep moving down the hall as it follows the curve of the hill. We look out the window, over the garden and down to the river. Then we are finally introduced to our host.

And do you notice where the novel begins? At the end of the third paragraph! There it is, bam: this is the story of how one hobbit had an adventure. So we have another source of tension: a hobbit went on an adventure. He found himself doing and saying things, and he lost . . . something. Found and lost, lost and gained: can you see the wonderful balance of the passage? We’re at the beginning, and we’re already talking about the end.

Tension comes from the juxtaposition of opposites, which we have plenty of in this passage. Suspense comes from things we don’t understand: we start by not knowing what a hobbit is, and we end by not knowing what the adventure is. And so we begin our story.

This is one of the most brilliant openings in English literature. By the end of the chapter, a great deal will have happened, and in the second chapter Bilbo will be off . . . no dawdling for the hobbit or Tolkien either. And from that second chapter on, he will always be in trouble. The narrator will be throwing rocks and rings and wargs at him.

These are the sorts of things we discussed in our workshop. In my next post on Stonecoast, I’ll talk about character . . .

February 2, 2015

A Still Place

I haven’t posted for a while, and it’s partly because I’ve been so busy. Mostly because I’ve been so busy. But there’s something else . . .

I feel as though I’m in a still place, a place of stasis. That’s not necessarily bad. Stillness is also peaceful, and I’ve been feeling less frantic than I have in a long time. It’s a good place: I love everything I’m doing. I love teaching undergraduate writing at Boston University, I love teaching my graduate creative writing students at Stonecoast. I have enough money to cover my living expenses and some luxuries, which certainly hasn’t always been the case. (Graduate school — ugh.) I live in a beautiful apartment, in a beautiful city. I just happen to have the best daughter in the world.

But it’s a strange place, too, because I’m not used to standing still. I’m used to things happening, to continually moving toward. Or, you know, away from . . . I’m used to a sense of motion, rather than stillness. It’s strange, for me, to think that I could stay here for the rest of my life, and it would be a perfectly good life. If nothing changed, I would be fine. Of course, that never happens. Things always change: if nothing else, I will get older. Nevertheless, if I stayed here, where I am, for a long time — it would be perfectly fine. And sometimes that fills me with a sense of panic.

I think it’s because I’ve spent my entire life moving from place to place, adjusting to new circumstances. Hungary to Belgium to the United States. Philadelphia to Washington D.C. to Boston. To Richmond to New York to Boston again. University of Virginia to Harvard to Boston University. And now here I am, having lived in Boston for a long time, having been at Boston University for more than ten years, as a student and then teacher. A great deal has happened in that time — and it’s really only in the last few months, since I settled into this apartment, that I feel as though I’ve arrived someplace. That I’m not just transitioning from one place to another. There’s something lovely about feeling settled. But I’m not used to it.

I suppose what I should be thinking is, I’ve come to a place that I can build on. Here, where I feel both strangely at peace and agitated from that strangeness, I can finally start to build what I want to, which is books — I want to build out of words. My first full-length novel is already with my lovely agent. I just sent him a synopsis of the second novel. And I do have so many ideas, for novels and stories and essays . . .

So I suppose my advice to myself should be: settle in and work.

The other thing I need to remember, to remind myself of, is that nothing ever stays the same. Stasis is, in the end, an illusion. The world may feel still, but it’s spinning. Everything we do, every choice we make, can change what happens. Who knows what will happen with this novel, or the one after it, or the one after that. The more we do, the more opportunities we are given to do things. And that sometimes means we are overwhelmed with work (ahem). But it also means we get to do amazing things . . .

I have already gotten to do a lot of amazing things. And I intend to do more.

So I need to take this stillness as the gift it is — a time when nothing seems to be happening, and I can maybe catch up, take a breath. Get ready for whatever is to come.

(These pictures are from our snowstorm last week. Today we are having another snowstorm, and once again university classes are cancelled. I don’t remember them being cancelled twice in one semester . . . ever. Not since I arrived here more than ten years ago. This is a particularly heavy winter, just right for being contemplative.)

January 15, 2015

Stonecoast: Raven Poems

I haven’t written a blog post in two weeks! It’s because I’ve been teaching at the Stonecoast MFA Program. Once I got over the flu, I only had a few days to prepare, and then I was off on the train up the coast, to Freeport, Maine. Stonecoast is a low-residency MFA program, one of the best in the country, and I’m very lucky that I get to teach there. I’m particularly lucky because Stonecoast has a Popular Fiction section, which means that I get to teach not just writing in general (although I certainly teach that), but also specifically writing fantasy, science fiction, and mystery. This time, I led a workshop specifically on writing fantasy and made a presentation on Agatha Christie’s plotting. In a low-residency program, students spend each semester working closely (but at long distance) with a mentor, and then they gather for the twice-yearly residencies. That’s where I was: the winter residency.

But now that I have some time to write blog posts, I’m going to write about my experience at Stonecoast. So I’ll tell you how my residency went . . . And the first thing I’m going to do is post some poetry. I arrived at Stonecoast last Friday and immediately plunged into greeting faculty members and old students, meeting the new students, and of course the work of the residency. That first night, we had our first reading, and I was one of the readers. I read two poems, both of them about ravens. So I thought I would reprint them here! In my next few blog posts, I’m going to describe some of the things I taught. Of course I can’t give you the full flavor of what it was like — you had to have been there. But it will at least give you a sense of what I did during the residency, and some thoughts on fantasy and mystery (the two genres I focused on this time), as well as teaching in general.

(People sometimes ask how they can take create writing classes with me. The answer is: at Stonecoast. That’s it, I’m afraid. It’s the only place I teach creative writing, to the Stonecoast MFA students. But if I teach any place else, I will post that information . . .)

So to start us off, here are the raven poems that I read, with expression of course, that first night:

Ravens

Some men are actually ravens.

Oh, they look like men.

Some of them in suits,

some of them in shirts embroidered

with the names of baseball teams,

some in uniforms, fighting in wars we only see

on television.

But underneath, they are ravens.

Look carefully, and you will find their skins of feathers.

Once, I fell in love with a raven man.

I knew that to keep him I had to take his skin,

his skin of feathers, long and black as night,

like ebony, tarmac, licorice, black holes.

I found it (he had taken it off to play baseball)

and hid it in the attic.

He was mine for seven years.

I had to make promises:

not to hurt ravens, to give our children names

like Sky, and Rain Cloud, and Nest-of-Twigs,

spend one night a week in the bole of an old oak tree

that had been hollowed out by who-knows-what.

I had to eat worms. (Yes, I ate worms.)

You do crazy things for raven men.

In return,

he spent six nights a week in my arms.

His black feathers fell around me.

He gave me three children

(Sky, Rain Cloud, Nest-of-Twigs,

whom we called Twiggy).

And I was happy,

which is more than most people achieve.

You know where this is going.

One day, I threw a stone at a raven.

I was not angry, he was not doing anything in particular.

It is just

that raven men are always lost.

Think of it as destiny,

think of it as inevitable.

I was not tired of our nights together,

with the moon gleaming on his feathers.

No.

Or maybe he found his skin in the attic?

Maybe I had taken his skin and he found it,

and he picked three feathers from it

and touched each of our children,

and they flew away together?

Maybe that’s how I lost them?

I don’t even remember.

Loving raven men will make you crazy.

In the mornings I see them hurrying to their offices,

the men in suits. And I see them in bars

shouting for their baseball teams, and I see them

on television in wars that have no names,

and I say, that one is a raven man,

and that one, and that one.

Sometimes I stop one and say,

will you send my raven man back to me?

And my raven children?

Some night, when the moon is gleaming,

the way it used to gleam

on long black feathers falling

around my face?

And here is the second poem:

Raven Poem

On the fence sat three ravens.

The first was the raven of night,

whose wings spread over the evening.

On his wings were stars, and in his beak

he carried the crescent moon.

The second was the raven of death,

who eats human hearts. He regarded me

sideways, as birds do. Shoo, I said.

Fly away, old scavenger. I’m not ready

to go with you. Not yet.

The third was my beloved,

who had taken the form of a raven.

Come to me, I said,

when darkness falls, although

I’m afraid you too

will eat my heart.

This is where I was staying last week, at the beautiful Harraseeket Inn, in Freeport, Maine:

And this is a bird’s nest I saw as I was walking down the snowy street, the last day I was there. It was filled with snow . . .

January 2, 2015

Calling in Sick

Yesterday, I called in sick.

Since it’s Winter Break, there was no one to actually call in sick to . . . so I had to call in sick to myself. In the ten years I’ve been teaching, I’ve only called in sick to cancel a class once, on a day when I could barely crawl to the phone to make the call. (This was back when I still had a landline.) Usually when I get sick, but not very sick, I have a conversation that goes something like this:

Body: I’m sick.

Mind: No, you’re not sick. I have a lot of work to do, so you can’t be sick.

Body: I’ll put off being sick until the weekend. But then I’ll really collapse.

Mind: Deal.

I’m very good at not being sick for a couple of days. And then I really get sick when I have time to. It’s something I learned back when I was in college, taking exams. I would study study study, take my exams, do well on them. And then I would go to bed for a week, sick from exhaustion. Nowadays I don’t have exams anymore, but the ends of semesters are just as intense, and I tend to overwork myself just as much. What’s changed is that I cut myself less slack. I assume that I should be able to (a) grade papers and submit final grades for almost sixty students, (2) make sure my graduating MFA students get in their final theses, (3) send a finished novel to my agent, and (4) prepare for Christmas, including the shopping and cooking and decorating, without getting tired or feeling ill. Gracefully, like some sort of academic Martha Stewart.

Instead, of course, I wake up one morning and decide that showering and making breakfast both sound like way too much work . . .

The problem with being a doctor’s daughter (and I’m the daughter of two doctors) is that one was never allowed to be just a little ill. When I told my mother that I felt sick that day, she would come take my temperature. And if I didn’t have a temperature that said “fever” to her, I had to go to school. After all, she dealt with children who were genuinely ill, who were being treated for diseases like cancer. What I was doing fell under the category of malingering. Now when I feel ill, the first thing I do is check my temperature. If it’s normal, I immediately say to myself, “I’m not sick.” The problem is, I never have a fever. The useful thing about being a doctor’s daughter is that when you call a parent and say that you have a pain in your side and it’s probably nothing, that parent can say “Go to the emergency room.” Several hours later, you are being prepped for an appendectomy. At first, the doctors didn’t think it was appendicitis, because . . . I didn’t have a fever. (Not having a fever when you have appendicitis is apparently some sort of bizarre medical anomaly. So I can say with some confidence, seriously I never have a fever. If I ever did, I would probably be convinced that I was dying.)

But if you feel ill, you are ill. The feeling itself is a symptom. If you’re so tired that you don’t want to do anything but lie in bed and watch British crime dramas, you’re ill. If you think a piece of toast and a boiled egg sound like a perfect dinner, you’re ill. If showering sounds like way too much trouble . . . Well, it’s time to call in sick. Also if you’re coughing and blowing your nose, but I tend never to trust physical symptoms.

Mind: You’re just coughing and blowing your nose to fool me into thinking you’re sick.

Body: Go. To. Bed.

Basically, I’ve exhausted myself. My body is completely out of whack, and I need to get it back in again. (Is there such a think as in whack?) And that means giving it what it needs, which is a lot of sleep, and rest, and time completely alone. So I’m letting it sleep whenever it wants to, as much as it wants. And I’m still doing the work that needs to get done before next week, but more slowly. I’m not bothering with going out, or seeing people, until I want to again. (I’m an introvert, so this is very much what I need.) Luckily, I have several pairs of pajamas. I have at least a couple of days until I run out of food. I will probably take a shower today . . . I have books and Netflix on my computer, so basically, I’m set.

I think every once in a while we just have to call in sick to ourselves. We just have to say, “I’m going to be sick. I’m going to be sick until I’m well again.” And then we have to sleep and sleep, and binge-watch British crime dramas, and drink herbal tea. I’ll know when I feel well again because I’ll decide that I’m just so bored, and I’ll want to see what the outside world is doing. I don’t think it will take long.

But until then, I’m going to be well and truly sick.

This painting is The Library by Elizabeth Shippen Green. I am nowhere near this elegant when I am sick. But let’s just pretend I am . . .

December 31, 2014

Why I Write

Last night, I stayed up late finishing the final edits to my novel manuscript before sending it to my agent for the second time. The first time I sent it to him, it was in the “well, I finished the novel but I’m still working on it because it’s not quite right, but here you can see that it’s finished” stage. This time it was in the “I hope you like it because honestly I can’t stand to look at it anymore” stage.

If you’re a writer and you’re sending manuscripts out, you know the stage I mean. It’s where you read through the manuscript on screen and decided to take out “that,” and then you read it on paper and decided to put “that” back in. And as you’re putting “that” back in, you stare at the screen, trying to read it both ways: with and without the word “that,” which really is only one of approximately 108,700 words in your manuscript. But there you are, agonizing over the one word. (“That” is one of my particular, personal problems. I did not realize this until an editor pointed it out and I did a word search on the short story she was editing. Sure enough, there were an awful lot of “that”s, about half of them unnecessary.)

These are the sorts of questions you ask yourself when you’re at that stage:

1. Should she have “dark brown” or “darker brown” hair?

2. Have I used the word “monkey” too often? (Word search for “monkey.”)

3. Do I need to mention that she left her umbrella at home? It wasn’t raining that morning.

4. How many characters are snoring? Is that too many characters? Do I need to cut some of the snoring?

5. Wait, where is her revolver? Is she holding it all this time?

I did, in fact, cut some of the snoring.

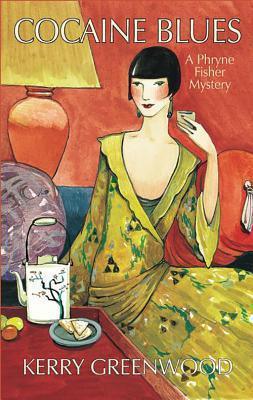

I sent the manuscript out around midnight, as an emailed document file, about 370 pages long (double-spaced). And then I celebrated by eating chocolate and watching two episodes of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, which took me to the end of Season 2. Now I have to wait until they film Season 3, which is entirely too long . . . If you haven’t heard of it, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries is an Australian television series based on the books by Kerry Greenwood. If your taste in stories and television shows is anything like mine, you will love them. I adore Phryne (pronounced Fry-oh-nee), her 1930s Lady Detective, and I have to admit that I’m in love with Detective Inspector Jack Robinson. But that’s based just on the television series, since I haven’t read the books . . . yet.

So there I was, sitting in bed, in pajamas, eating dark chocolate with sea salted almonds in it, watching Miss Fisher on my computer (I don’t have a television). Thoroughly enjoying myself. And I thought: this is why I write. Because someday, someone might need something to entertain them, or cheer them up, or even just pass the time. And maybe my book will do that.

I think that’s worth all the agonizing over “that.”

It’s fair to say this novel took me two years to write: the first few chapters were written earlier, but I had to rewrite them after I finished my PhD and moved into my previous apartment. I had been thinking about the novel in the wrong way, and it took the mental freedom of having finished my degree to get it right. That apartment was where I really wrote the novel, finishing it last summer in Budapest and then adding the final chapters when I moved into this apartment, in August. Since then, I’ve been revising. And of course there has been a lot of revising along the way . . . Sometimes I think it’s pretty good, sometimes I worry that it’s awful and I just can’t see its awfulness. But I figure, it’s only the first full-length novel I’ve written, so if I mess up the first time, I’ll get it right the second time. Or the third. Or fourth. I’ll just keep writing . . . Someday, there will be a woman in pajamas, with chocolate, and she will stay up late to read something I wrote. Or maybe even watch something based on it, on her television screen!

So thank you, Kerry Greenwood, for doing that for me. You don’t know me from Eve, and you’re all the way on the other side of the world, in a country I’ve never visited, but you gave me two lovely hours. Oh yes, a television show is always separate from the book, although based on it. But it would not have existed without you, sitting in a room, probably in front of a computer, agonizing over that final draft. Just like me.

These images are from the Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries television show and the first book in the series, which I now want to read . . .

December 28, 2014

Writing Lesson: Observation

I thought it might be interesting to put down some of the things I’ve learned from teaching writing. From writing too, of course, but I find that when I teach writing, I tend to make certain points over and over. Because these are the sorts of things that many writing students need to work on. So I thought they might be interesting to point out here as well, for those of you who are writers, or who simply want to improve your writing . . .

The first one I want to talk about has to do with observation. If you want to be a writer, you need to also be an observer . . . someone who is curious about the physical world around you. I don’t know about you, but I find it harder to write about the physical world than about mental states. It’s easy enough to describe what someone is thinking, but try to describe someone walking down stairs. I mean, in a way that makes it interesting.

(Ironically, writing students often think the way to keep a narrative interesting is to include action scenes. But action scenes can get very boring, very quickly. It’s often less interesting to watch a character act than to hear her think. Physical actions are usually interesting to the extent that they illuminate something else: the character herself, the world in which she is acting, etc.)

When describing the physical world, it’s very easy to fall into clichés. And the best way to avoid clichés is to observe closely, to see things as they are instead of as people say they are. To see what actually is.

So here is an exercise for any writers among you: go and observe. I do it sometimes sitting on the metro, where I can see so many faces, all different. I think about what makes them different, what distinguishes them from one another. I try to remind myself to observe, because it’s so easy not to see, isn’t it? To go through our days, particularly when we’re busy, and simply miss what is around us. The colors of leaves on the sidewalk. The different kinds of stone in the buildings. And the world is hard to describe anyway, because it’s so specific, each part of it different from every other part, and yet the words we have are “gray stone” and “autumn trees,” and it’s hard for writing to get at that specificity. But we have to try.

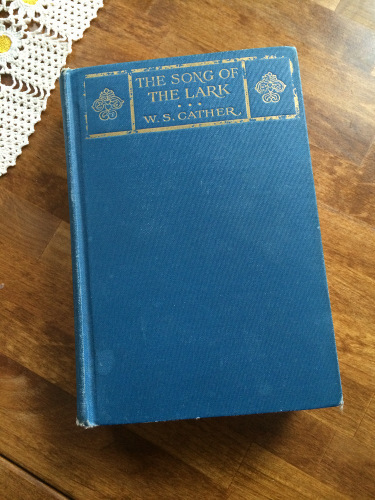

I was thinking about this recently as I read a description of a character in Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. The description comes right at the beginning of the book, two paragraphs in:

“Dr. Archie was barely thirty. He was tall, with massive shoulders which he held stiffly, and a large, well-shaped head. He was a distinguished-looking man, for that part of the world, at least. There was something individual in the way in which his reddish-brown hair, parted cleanly at the side, brushed over his high forehead. His nose was straight and thick, and his eyes were intelligent. He wore a curly, reddish mustache and an imperial, cut trimly, which made him look a little like the picture of Napoleon III. His hands were large and well kept, but ruggedly formed, and the backs were shaded with crinkly red hair. He wore a blue suit of wooly, wide-waled serge; the traveling men had known at a glance that it was made by a Denver tailor. The doctor was always well-dressed.”

This, by the way, is what Napoleon III looked like:

But I can imagine Dr. Archie without that image. He’s stuck in a small town in Colorado, but I know he will be a strong character, simply from the way he’s described. It’s a long description — you probably would not find one as long in a modern novel, since novels now are expected to move at a faster pace. But Cather avoids any clichés. She includes generalizations (“always well-dressed”), but also backs them up with specifics (the Denver tailor). And notice the information she does not give us: we don’t know the color of his eyes. It’s standard in student writing to find a description that focuses primarily on hair and eye color. Here Cather gives us hair color, but not just on Dr. Archie’s head. We also learn about his mustache and the hair on the back of his hands. We do learn that his eyes were intelligent, which is actually what we most need to know about him.

Do you see what she’s doing? She’s describing what we would probably notice if we actually met Dr. Archie. These are the things about him that stand out, that make him different from other people. That are specific to him.

So when you’re observing, you really have to observe two things at once: what is in front of you, and yourself noticing. You have to see how you’re seeing. And not just what is static, but also gestures. Here Cather gets gesture in a bit with the stiff shoulders; it’s a static description, but we get a sense for how he holds them, for how Dr. Archie moves. When you’re observing, think about how people move, how they walk down stairs, or put their hand on the railing, or look back up when they reach the landing. How do they turn back their heads? What do their gestures look like?

It occurred to me, writing this post, that writing handbooks often tell you how to write, focusing on the craft of writing itself. But they don’t often tell you how to be a writer: how to prepare yourself to write. How to go through the world as a writer, finding and absorbing the material you will need. Because writing doesn’t come out of your head. Oh, if only it were so easy! No, writing comes out of other writing, and out of your lived experiences. If it comes only out of other writing, it’s merely imitative. If it comes only out of lived experiences, it’s often unformed, uninformed. Like a long diary entry, uninteresting to read. Good writing happens when you’ve absorbed a great many things, both from books and from life, and they’ve mixed pretty thoroughly in you, as though you were a cocktail shaker. And then you pour it out, into whatever form you’ve chosen or it’s chosen for itself (whether a poem, or short story, or novel).

So if you want to be a writer, give yourself homework: go out and observe.

This, by the way, is my copy of The Song of the Lark, from 1924.