Theodora Goss's Blog, page 13

December 6, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Death and Disguise 2

I was reminded recently of how the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey that I’m describing might be helpful to people: or at least to me.

If you’ve been following this blog, you know that I teach a university class on fairy tales. As I taught some of the most familiar fairy tales, by the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault, I realized that they often contained a very specific kind of heroine’s journey. So I started trying to describe it. I’m not a psychoanalyst or anthropologist; I don’t think of this journey as universal, in the way Joseph Campbell described his hero’s journey. Despite my respect for Campbell, I’m dubious of the univeralizing tendency. Among other things, it glosses over important cultural and historical differences. All I claim for the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey is that it’s a narrative structure we see in some fairy tales: the ones I’ve studied so far are European and usually go back to the middle ages. I think of it as a meta-tale type.

You might be familiar with tale types, which is a way that folklorists categorize fairy tales: different fairy tales that share common elements will be categorized as Cinderella-type tales, because there will be the wicked stepmother, the small shoe, even though in one version the Cinderella figure will be given clothes by a fish, in another a cow. Tale types also elide some cultural and historical differences, but at least they are aware of them. They do not try to say there is one Cinderella story underlying all Cinderella stories, or even all stories. They acknowledge that there are many different kinds of stories we can tell, and some of them have certain similarities. They also help us understand the historical development of fairy tales: Cinderella, for example, may originally have been Chinese. But we don’t know for sure, and for me that phrase, “We don’t know for sure,” is the hallmark of good scholarship. A scholar always tells us what she does not know.

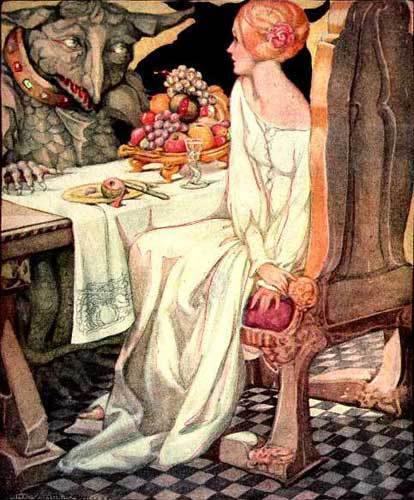

So here I am, trying to describe a pattern I see in a number of different tale types. If you want to see the pattern itself, take a look at the “Journey” page on my website, where I list the steps of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey and link to the various posts I’ve written about it. In my last post, I talked about the step where the heroine dies or is in disguise. Is it one step? Somehow, the death and disguise seem related to me. There’s Snow White in her glass coffin, the Sleeping Beauty in her forest of thorns. Rapunzel is not dead in her tower, but it too seems like Sleeping Beauty’s tower, a place of stasis. Meanwhile you have Cinderella and Donkeyskin in disguise, as servants — they even lose their names. The same sort of thing happens to the Goose-Girl. There is a variant in which the heroine’s true love is the one dead or in disguise: this happens in the “Animal Bridegroom” stories like “Beauty and the Beast” and “East o’ the Sun, West o’ the Moon.” In my last blog post, I connected this period of loss and stasis to the liminal state, the middle stage in a rite of passage. We must pass through a liminal state, a little death, in order to be transformed. It was a very technical sort of blog post.

And then I had a personal experience that highlighted for me why any of this might be important. It’s the end of the university semester; I’m exhausted. For the past few weeks I’ve been working every day, late into the night. During the day, I’ve been planning and teaching my final classes. On days I don’t teach, I’ve been meeting with students for up to five hours a day. In the evenings, and sometimes until the small hours of the morning, I’ve been reading and commenting on papers, answering emails. This weekend, for the first time, I have some free time before the final papers and portfolios come in, at which point I will be grading for a solid week. As you can imagine, I was feeling tired and rather down, getting my work done but dragging myself through the days. I got to Thanksgiving, which is a break for us, and all I wanted to do was watch British murder mysteries or baking competitions, which are surprisingly alike in their underlying narrative structure. And I thought, what is wrong with me? I blamed myself — perhaps I had planned the semester wrong? (No, semesters are like this for every professor who teaches writing.) I tried to push myself, but every time I did, I just got more tired, more despondent.

And then I had a revelation: I’m not in the dark forest. I’m in the glass coffin.

If you’ve read the structure of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, you know that there is a stage where the heroine must go through the dark forest. It’s usually fairly early on in the tale. The important thing about the dark forest is that you don’t die there. You’re lost, you’re scared, you’re usually alone, after you get rid of the huntsman who was sent to kill you . . . but you’re not going to die. The dark forest is simply something you have to get through, and it usually represents your fears, your encounter with the darkness in yourself and the world.

The lesson of the dark forest is: keep going.

The stage where you die, where you end up in the glass coffin, is usually a separate stage. (Except in “Sleeping Beauty”: she’s dead and in the dark forest at once. In tale types, and in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, there’s always an exception.) The lesson of the glass coffin is that you will be revived. You will eventually wake up. In fairy tales, death is temporary. In this way, I think, fairy tales hark back to a pagan past and a time when life was seasonal, cyclical. The year died and was born again. The people who originally told these tales lived in continual cycles — of the seasons, of life and death, of the pagan or later Christian festivals that marked the stages of the year. Even their daily lives were governed by the rising and setting of the sun in a way ours aren’t. When they became Christian, death was still figured as a rebirth.

The lesson of the glass coffin is: rest now.

What does that mean? It means that sometimes you are tired, and sometimes you are in a state of transformation, and in those times you must accept that you need rest. Don’t keep going. Instead, crawl under the covers. Watch British murder mysteries and baking competitions. This isn’t the time to power through. The journey includes periods when you’re not traveling, and you need to accept that. Sometimes, you won’t be going anywhere for a while. And that’s all right.

So I did: I rested. And afterward I felt better.

It helped me to have a model of the journey, to understand where I was on that journey. Because the journey itself, and this is one of my hypotheses, is based on women’s actual lives. Oh, not the lives we live now: no, it’s based on what women’s lives were like hundreds of years ago. But the underlying structures of those lives, the leaving home, going through dark forests, finding friends and helpers . . . all those fundamental things are still parts of our lives, and learning the patterns can help us identify them in our own lives. They can help us live the lives we live now, consciously and well.

(This illustration is by Louis Rhead. I chose it because the Queen looks so contemplative: here she looks less as though she’s admiring herself in the mirror and more as though she’s asking what it’s all about, anyway.)

December 5, 2015

Why You Might Be a Witch

Why You Might Be a Witch

by Theodora Goss

Because sometimes you dream of flying

the way you used to.

Because the traffic light always changes for you.

Because when you throw the crusts of your sandwich

to sparrows in the public park, they hop close

and closer, until they perch on your finger

and look at you sideways.

Because as you walk down the street,

the wind plays with the hem of your skirt

so it swings dramatically around your ankles.

Because as you walk, determined and sensible,

your shadow is dancing.

Because a lot of people talk to cats

but for you they answer.

Because the sweetgum trees along the sidewalk

love to show you their leaves, sometimes even tossing

them in front of you, yellow veined red,

brown shot with green and yellow,

like children showing off artwork.

Because when you look up,

the moon is always smiling.

Because sometimes darkness closes around you

and you remind yourself that it’s all right,

you’ve worn this cloak before.

Because in winter you acknowledge

that snow is a blanket as well as a shroud,

and we must all sleep sometimes.

Because in spring you can hear the tinkling bell-sounds

that crocuses make, and the deeper gongs of the tulips.

Because the river waves to you in passing,

and you wave back.

Because even the brownstones of this ancient city

look at you with concern: they want to make sure you’re well.

You belong to them as much as they to you.

Because witches know what they are

and if I asked, do you remember?

You would have to confess that yes,

you do.

(The illustration is by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

December 2, 2015

Lady Winter

Lady Winter

by Theodora Goss

My soul said, let us visit Lady Winter.

Why? I responded. Look, the leaves still lie

yellow and red and orange in the gutters.

The geese float on the river. On the sidewalks,

puddles continue to reflect the sky.

My soul said, the branches are bare.

And you can feel it, can’t you, in your bones?

The chill that is a promise of her coming.

The year is growing older. Anyway,

you haven’t seen her in so long: it’s time.

We put on our visiting hats.

I stood admiring myself in the mirror

while my soul stood beside me looking pensive

and pale. Was she a little sick? I wondered.

Lady Winter lives on an ancient street

lined with elms that canker has not touched,

in a tall brownstone with lace curtain panels,

empty window boxes, two stone lions.

We rang the bell and heard it echoing.

A maid opened the door. Her name is Frost.

My lady looked the way she always does:

white hair, a string of pearls, rings on her fingers,

age somewhere between forty and four thousand,

a kind, implacable smile.

She said, my dear, what’s wrong? You don’t look well.

What, me? I’m fine. Perfectly fine, I said.

My soul just shook her head.

My lady has a parlor with a fireplace

in which I’ve never seen a fire. Instead,

it’s filled with decorative branches. Doilies

lie like snowflakes on the tables, bookshelves,

over the backs of armchairs.

She’s always wearing a gray cashmere sweater

and expensive shoes. She must have a closetful.

She usually serves us tea and ladyfingers.

But this time she said, I want you to go to bed.

Frost will take you upstairs, then I’ll come up

to cover you in blankets of felted wool,

comforters stuffed with down from eiderducks

that nest by Norwegian fjords. I’ll read you books

of fairytales about bears and princesses,

and stolen crowns, and castles beneath the sea,

and northern lights.

Grandmothers who grant wishes, talking reindeer,

a village in the clouds.

I’ll talk to you until you fall asleep.

Your soul will sit and watch through the long night.

From time to time she’ll take your temperature

to make sure you’re all right.

So I lay down in Lady Winter’s guest room:

reluctantly, but it looked so inviting,

a bed with draperies and a painted ceiling

from which the moon was hanging

by a silver chain.

My soul sat down beside me.

Don’t worry, she said. There’s plenty for me to do.

Poetry to embroider, plans to knit.

I’ll wake you when the crocuses have broken

through the black soil, when warmth has come again.

Then Lady Winter put her soft, dry hand

like paper on my forehead

and she said

rest now.

(The image is by Elizabeth Sonrel.)

November 28, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Death and Disguise

At some point during the fairytale heroine’s journey, she dies. Or she’s in disguise: actually, it’s much the same thing.

You remember the fairytale heroine’s journey, right? I haven’t written about it for a while, because I’ve been so busy. But today I thought I would return to it. Here, in case you’ve forgotten, are the steps:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine meets friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

So now we’re on Step 8, and here the strangest thing happens, and it happens in so many fairy tales: the heroine essentially loses herself. Snow White dies from the apple and is laid in her glass coffin. Sleeping Beauty sleeps for a hundred years. Cinderella and Donkeyskin are disfigured by ashes and the donkey’s hide: no one knows who they truly are. The Goose Girl is disguised as a goose girl, of course. In “Six Swans” the heroine must stay silent for seven years. Rapunzel is in her tower, just as Sleeping Beauty is in her forest. Vasilisa is in Baba Yaga’s hut, which is a place of the dead. The heroine is immured, lost to the world in some way. And lost to herself. The exception is “Beauty and the Beast”-type tales, which includes “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon.” In those tales, it’s the male love interest who dies or sleeps, who is lost. The heroine’s task is to find him, to recognize him — which as we will see is the next step. But in most of the tales I’m familiar with, it’s the heroine herself who dies or is in disguise for a while.

One of my hypotheses is that this pattern is so strong, it gets put onto fairy tales that didn’t originally contain it. So for example, oral versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” did not include Little Red being eaten by the wolf. “Little Red Riding Hood” is not part of this family of tales about a woman’s development, from birth to marriage. But in the Grimm version, we have the disguise: Grandmother is really the wolf. And we have the death: Grandmother and Little Red in the wolf’s belly. The logical outcome would be for Little Red to marry the Hunter, and I bet someone has written or will write that version, because in fairy tales, patterns have a way of playing themselves out.

But anyway, back to our dying, disguised heroines. Why do they die? Why must they lose themselves?

My theory is that fairy tales reflect a mishmash of old stories, customs, rituals . . . and of course history. All sorts of things went into the making of fairy tales. Medieval famines went into them, and myths went into them, and the patterns of ritual went into them. I think that’s partly what we have here. What this death and disguise reminds me of, more than anything else, is a rite of passage. That pattern was described by Arnold Van Gennep in The Rites of Passage, which I read in graduate school. Van Gennep studied rites of passage from all over the world and concluded that they all share a three-part structure: they all have a pre-liminal stage, a liminal stage, and finally a post-liminal stage. So what is “liminal”?

A “limen” is a threshold: it’s the thing you cross over when you step through a door. At least, if you’re doing it in Latin! In a rite of passage, the pre-liminal state is stable: it’s the stage you were at before things changed. The post-liminal stage is also stable. So, for example, in a rite of passage you might change from a boy to a man, or an unmarried girl to a married woman. (I use those examples because they are two of the most common, and yes, rites of passage are usually gendered.) The liminal stage, between them, is unstable. It’s dangerous: to the person undergoing the rite of passage, and to anyone connected to that person. It must be closely supervised, protected by ritual. As traditional societies know, to change is to be in peril, at least for a while. The typical plot of the Victorian novel is this: “a rite of passage goes awry.” Usually the rite of passage is marriage, and poor Jane Eyre is left at the alter in her ritual wedding gown. What she must undergo next is a symbolic death on the moors, sleeping on the earth as though in a grave. I think it’s important that Charlotte Brontë made Jane’s rite of passage not marriage, but communion with the earth, which is described as a great mother.

Back to our fairy tale heroine. It was once common for girls, as well as boys, to go through rites of passage. These tended to disappear over time . . . But the important thing, for understanding fairy tales, is that girls did once go through them, and the central stage of the rite of passage, the liminal stage, often involved a ritual death. Disguise was also a kind of death: young boys would be sent out into the wilderness, where they would ritually become animals. They were dead to the human community. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that just as society was losing so many of its traditional rites of passage, the color of a wedding dress changed. Yes, fashions were following Victoria, and white is the color of innocence, a virginal color . . . but it’s also the color of a shroud. I think that’s why in the West, white has stuck as wedding-dress color. A bride also looks like a corpse. So the girl undergoing a rite of passage is ritually dead, or ritually something other than what she is — she is in disguise.

That’s what we have in fairy tales: a memory, an echo, of the rite of passage.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? If these particular types of tales, the fairytale heroine’s journey tales, were about the progress of a woman’s life, they would include a rite of passage in which she changes from a girl into a woman. That’s exactly what we have in Snow White and Sleeping Beauty. Some scholars have seen these instances of being dead as examples of extreme passivity, but because they occur so frequently in fairy tales, and are not always associated with being passive, I would call them times of transformation. It particularly interests me that they’re often associated with hearths. The Goose Girl must crawl into a hearth and whisper her secrets before she is recognized. Cinderella’s disguise comes from the hearth. Donkeyskin works in a kitchen, next to the hearth. Why a hearth? Well, for one thing, the hearth is a sacred space. It’s where food is cooked, where what is inedible is transformed into the edible. The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss identified the difference between raw and cooked as the central difference between primitive and civilized. The hearth is the symbol of civilization itself. It was once presided over by the goddess Hestia or Vesta, who is one of the most important goddesses of the classical pantheon. (We tend to forget her, because there aren’t a lot of stories associated with her. But in actual belief and ritual, Vesta was absolutely central. She’s the one to whom the Vestal Virgins owed allegiance, and they kept the sacred fire of Rome itself lit.) The hearth is where transformation happens, and it’s also a tomb. In ancient belief, life was most often seen as a cycle: before things were born, they had to die. The hearth is a symbol of that. And hearths were sometimes used for burials . . .

Is it all starting to make sense? What I haven’t yet touched on is what use we, as modern human beings, can make of this. Perhaps that has to wait for another post. But the important thing is that before she can reach her happy ending, the fairytale heroine has to die or lose herself in some way. Or, in the “Beauty and the Beast” variant I described above, she has to revive or recognize the man she loves. But more on that another time . . .

This painting of Snow White in her coffin is by the Austrian painter Marianne Stokes.

November 26, 2015

The Witch-Girls

The Witch-Girls

by Theodora Goss

The witch-girls go to school just down the street.

I see them pass each morning with their brooms

and uniforms: black dresses, peaked black hats.

They giggle just like ordinary girls,

except that as they walk, their brindled cats

twine around their ankles. One will stop

and say, “You’ll trip me, Malkin,” scoldingly.

Then Malkin will look up and answer back,

“Carry me then.” The witch-girl will bend down,

scooping the cat into her arms, and perch

him on her shoulder. So the witch-girls pass.

I wish I could be one of them. Alas,

I don’t know how to fly on windy nights

or talk to bats, or brew a magic potion.

Although I think I could be good at witching.

I’d learn to curse and never comb my hair.

I’m pretty good at scaring passers-by

by making goblin faces through the window.

I’d trade white cotton dresses for black wool,

no matter how it itched. I’d fly my broom

up to the witches’ garden on the moon

where they dance nightly, kicking up their heels

with sylphs and fauns and ghouls. At least I think

that’s what they do. I don’t think witches go

to bed at nine, or even make their beds

each morning. No. Instead, they marry toads,

or live alone and read old books. They paint

landscapes in Germany, or climb the Alps,

or sit in Paris cafés eating chocolate

for lunch and maybe dinner. They get drunk

on elderberry cordial, speak with bears

on earnest topics like philology.

I wonder what the witch-girls learn in school?

Geometry that helps them walk through walls,

and how to turn a poem into a spell . . .

I wish that I could go to school with them.

I’d giggle and be wicked too, if they

would only let me.

(This image is “The Little Witch” by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

November 25, 2015

The Gold-Spinner

The Gold-Spinner

by Theodora Goss

There was a little man, I told him.

I gave the little man my rosary,

I gave the little man my ring,

my mother’s ring, which she had given me

as she lay dying. A thin circlet of gold

with a garnet, fit for a commoner.

As I was a commoner, I reminded him.

Nothing magical about me.

Very well, he said. You may go

back to your father’s mill. I have no use

for a miller’s daughter without magic in her fingers.

I’ll keep the three roomfuls of gold.

I walked away from the palace, still barefoot,

still dressed in rags, looking behind me

surreptitiously, afraid he would change his mind.

Afraid he would realize he’d been tricked.

I mean, what kind of name

is Rumpelstiltskin?

But he would have kept me spinning

in a succession of rooms, forever.

I passed my father’s mill without entering,

either to greet or berate. I wanted you to be queen,

he had told me, after I said how could you

betray me like this?

You deserve that, you deserve better

than your mother. What kind of life

did I give her?

No, I wasn’t going back there.

By mid-afternoon I had left the town,

I had forded the river, I had come

to unfamiliar fields. I sat me down

by a hedge on which a few late roses bloomed

and from a thorn I plucked a tuft of wool

left by a passing sheep. I spun,

twisting it between my fingers

as my mother had taught me.

She, too, had the gift.

I coiled the resulting thread

of thin, soft gold

around my wrist. Somewhere along the road

it would buy me bread.

Until then, there were crabapples

and blackberries to share with the birds.

And the road ahead of me,

leading I knew not where, but somewhere different

than the road behind.

(The illustration is by Anne Andersen. Except in my poem, of course, there is no little man . . .)

November 18, 2015

The Stepsister’s Tale

The Stepsister’s Tale

by Theodora Goss

It isn’t easy, cutting into your feet.

Years later, when I had become a podiatrist,

I learned the parts of the feet. Did you know that your feet

contain a quarter of your bones? Calcaneus, talus, cuboid, navicular.

Lateral, intermediate, and medial cuneiform.

Metatarsals and then the phalanges, proximal, middle, distal.

They are beautiful on the tongue, these words from a foreign language.

My sister cut into her heels, which are in the hindfoot.

I cut into my big toes, called the halluces.

She cut into flesh and tendon and sinew.

I cut into bone, between the phalanges,

through the interphalangeal joint.

That’s in the forefoot, which bears half the body’s weight.

To this day, both of us walk with a slight limp.

The problem is that you do desperate things for love.

We loved her, the woman who wanted us to be perfect:

unblemished skin, waist like a corsetier’s dream,

feet that would fit even the tiniest slipper.

And so we played the aristocratic game

of identify-the-princess.

Sometimes it’s a slipper, sometimes a ring.

Oh mother, love me without asking me to scrape

my fingers like carrots, cut off my heels and toes.

Eventually, she became your favorite daughter,

the cinder-girl, the princess-designate.

She was the best at being perfect, but abuse

will do that to you.

A woman comes into my office, asking me

to cut off her little toes so she can wear

the latest fashion. I sit her down and say

did you know that your feet provide the body

with balance, mobility, support?

Come, let me show you a model: here’s the toe,

metatarsal and phalanges. You can see

how elegantly they move, as in a waltz,

surrounded by your blood vessels and nerves,

the ball gown of your soft tissue,

a protective coat of skin, the delicate nail.

Look, underneath, how beautiful you are . . .

(This illustration is by Charles Folkard, for an edition of Grimms’ fairy tales.)

November 14, 2015

The Morning After

The Morning After

by Theodora Goss

Even on the morning after

a great tragedy, the world is still beautiful.

Should it be? I don’t know.

Perhaps after the slaughter, after

the bodies lying in a field, the houses burning,

the clouds should no longer continue intermittently

concealing and revealing the sky. Perhaps the leaves

should stop turning orange and yellow and red.

Perhaps they too should honor the dead.

But they don’t.

If anything, the world says to us:

my strange, impermanent children,

look at my mountains. Learn to breath, as they do.

Look at my forests, at the trunks of trees that have grown

over a century. Or the grasses, renewed annually.

They live and die, yet are no less important than the rocks.

The moth that lives for a day is as precious

as the tortoise.

Learn to love what you are: a part

of the whole. Do not divide yourself.

Do not think you are alone, or you alone

walk this earth. The wolves slip through the forest

and above you, the wild geese are calling.

You are part of the family: let that be

not frightening but reassuring.

This morning, the river will not mourn with you.

It will continue to flow, as it has since before

you were born. But as you memorialize the dead

again, for this has happened before, it will remind you

that beyond strife and sorrow and anger,

the leaves are turning. That it is autumn,

and the swallows are preparing

once again to fly south.

November 8, 2015

Beauty to the Beast

Beauty to the Beast

by Theodora Goss

When I dare walk in fields, barefoot and tender,

trace thorns with my finger, swallow amber,

crawl into the badger’s chamber, comb

lightning’s loose hair in a crashing storm,

walk in a wolf’s eye, lie

naked on granite, ignore the curse

on the castle door, drive a tooth into the boar’s hide,

ride adders, tangle the horned horse,

when I dare watch the east

with unprotected eyes, then I dare love you, Beast.

This image of Beauty and the Beast is by the Scottish painter and illustrator Anne Anderson. I particularly like it because it shows a beast that is genuinely beastly — not handsomely leonine. And it shows Beauty’s reluctance, in the half-turned body. But the Beast also looks gentle and concerned, as he is in the story by Madame de Beaumont.

I wrote this poem a long,long time ago — when I was in law school. It’s still a favorite of mine. If you would like, you can hear me read it:

This poem, and many more, can be found in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

November 7, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Meeting Friends and Helpers

It’s been a while since I posted on the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey. What I’ve decided, in the last week, is that after I finish the book I’m currently writing, I’m going to write a book that brings together all the elements of the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey, and see if I can find a publisher for it. But in the meantime, I’m going to keep blogging about it, trying to generate the material from which I will write the book. That will allow me to think aloud, and also, if you want to, allow you to come on the journey with me.

Today I want to write about the fifth step in the process: The Heroine Meets Friends and Helpers.

In fairy tales that contains a heroine’s journey (not all of them do, of course), we usually find friends and helpers. Vasilisa the Beautiful has her doll, who helps her do the required chores in Baba Yaga’s hut. Snow White is most famous for the dwarves who help her out: in the Grimm version, they are simply seven dwarves, but Disney gives them names and personalities. He also adds the forest animals who help Snow White do housework in the dwarves’ house, and comfort her in the dark forest. (As we have seen, entering the dark forest is step three in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey). In the Grimm’s version of “Cinderella,” Aschenputtel is helped by the birds that perch in the hazel tree growing on her mother’s grave. They help her sort lentils from the ashes, they give her dresses and shoes for the ball, and in the end, they peck out the stepsisters’ eyes. (Yes, I know, that’s such a harsh conclusion — why would friends and helpers do that? We’ll have to discuss the harsh conclusions of fairy tales later in the series.) In a Chinese Cinderella-type story, “Yeh-hsien,” the heroine is helped by a fish that she has fed and nurtured.

One thing we’re seeing so far is relationships of reciprocity: the dwarves take care of Snow White, and she keeps house for them. Aschenputtel cares for the hazel tree growing on her mother’s grave, and the birds in the tree help her. Yeh-hsien takes care of the fish, and even after her stepmother kills it, its bones give her clothes for the festival. The other thing we’re seeing is the power of a protective parent. Vasilisa’s doll was a gift from her mother. The hazel tree grows from Aschenputtel’s mother’s grave, and it’s clear that the gifts and protection come from her. In Perrault’s version of “Cinderella,” the fairy godmother has a parental relationship with the cinder-girl. She is, in a sense, a substitute mother figure. (Godparents did, indeed, have important roles in seventeenth-century France. They often provided what the parents could not, including financial help.) In “The Goose-Girl,” the heroine’s friend and helper is the horse Falala, whose head continues to speak even after it has been cut off. What that head does is confirm her identity: it’s the only entity that knows she is still a princess, not a goose-girl. And it’s also linked to her mother: as she passes the head each morning and evening, it says,

“Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare!

If this your tender mother knew,

Her heart would surely break in two.”

There’s a sense in which Falala speaks for the mother, who is not there to protect her daughter.

In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine is helped by the three old women who give her golden objects, with which she can rescue her bear husband. She is also helped by the winds, who take her to that impossible place, where he is being kept by a troll queen and princess. In “Sleeping Beauty” we have the fairy who mitigates the curse of death. In the Basile and Perrault versions, we also have the cook who saves Sleeping Beauty and her children. In the Basile version, “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” a king finds and impregnates Talia (the Sleeping Beauty) while she is still asleep. She has two children, Sun and Moon. She wakes when the two children, seeking her breasts to suck, instead suck on her fingers and draw out the piece of flax that has been lodged under a nail. Once the flax is out, she wakes up again. The king’s wife (yes, he has a wife) finds out about Talia and is understandably jealous. She summons Sun and Moon to the palace, where she has them killed and served up to the king. Then she summons Talia, whom she plans to burn in a fire. At the last moment, the king finds out what has been happening and saves Talia. Then the cook confesses that he has saved Sun and Moon, who were not killed after all, and served the king ordinary meat instead. The queen is burned instead of Talia, and the king, Talia, Sun and Moon live . . . happily ever after? I don’t know, this is a depressing version, isn’t it? It’s very much of Basile’s time, the Renaissance: a tale of power struggle, violence and violation, cannibalism. Its basic structure resembles Greek tragedy or Jacobean drama, not what we’re used to in a fairy tale. For me, it’s a useful reminder that the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, as it has come down to us, does not have a simple or purely positive history. That history contains messages about women’s lives that we will want to both examine carefully and potentially reject. That is why the journey is continually being rewritten. Perrault, making his version of “Sleeping Beauty” more respectable for a French aristocratic audience, turns the king’s wife into his mother, who is an ogress. She wants to eat the princess and her two children, simply because ogresses enjoy human meat. In this version, the cook saves all three of them. The Grimms take out this entire episode, ending with the kiss of true love and the marriage of prince and princess. Their version, “Briar Rose,” was revised specifically for children, so rape and cannibalism had to be taken out. (Although other tales in their collection are dark enough!)

In “Beauty and the Beast” we also have a fairy: no surprise, since it’s a French fairy tale. The French fairy tales are chock full of fairies, whereas the Grimms tried to take them out, deeming them too French . . . So in French versions, helpers are often fairies, whereas in other traditions, closer to the oral folktales, they are more likely to be animals or old women who are actually witches. (Lesson of the fairy tale: always be kind to old women or animals, because you never know what power they might have.) I don’t remember friends and helpers in “Rapunzel” or “Six Swans,” so they don’t necessarily appear in every story. But the pattern is clear enough that I think we can conclude finding friends and helpers is part of the pattern. And this is important: when these elements of the journey don’t appear in one version, they often appear in another. In Andersen’s “The Wild Swans,” the queen of the fairies helps Eliza, the girl whose brothers were turned into swans. She appears first as an old woman and then in her own beautiful form and tells Eliza how to break the spell. It’s as though this pattern is imprinted in us somewhere, and later storytellers will often add what is missing in earlier versions. So, for example, Disney added the three helpful fairies to his animated version of “Sleeping Beauty,” and he sent his Princess Aurora into the dark forest, although the only dark forest in earlier versions is the one that grows up around her.

I’ve spent a lot of time here talking about the tales, and not what they mean to use. But I think the lesson is that we need to find our own friends and helpers. Often, we find them when we need them most, in the dark forest, as Snow White did. If we can take some lessons from this portion of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, I would suggest the following:

1. When you’re lost and alone, in the dark forest (even if it’s a dark forest of the soul), look around for your friends and helpers. You might be surprised to find they’re there with you. Let them help you . . .

2. Give back, be a friend and helper yourself. Even if you’re the heroine, clean the dwarves’ house, take care of the magical fish. Reciprocate for the care and friendship you receive.

3. Never discount the friendship of animals or old women. They may help you when everyone else has turned away . . . And they might be a lot more powerful than you expect.

This illustration for “Cinderella” is by Margaret Tarrant.