Theodora Goss's Blog, page 11

April 18, 2016

Shabby and Chic

I’m infinitely grateful to Rachel Ashwell.

Unless you’re interested in decorating, you probably don’t know who she is. She’s the decorator and designer who, in the 1990s, introduced the idea of Shabby Chic. It was very influential at the time, I suppose because everyone was so used to perfectly decorated houses being the standard to which we should all aspire. That was the ideal sold by the decorating magazines, and it mostly still is.

Shabby Chic was the idea that the things you had could be shabby — old, worn, cracked. But if they were beautiful, you could still decorate with them and create something chic — in fact, more chic than you could create with an entire roomful of perfectly-matched furniture. It was based on English country house style, as well as the continental style found in old apartments in Paris, old castles in Tuscany. It was the style of people who had inherited things and didn’t throw them away. The appeal was that this fundamentally aristocratic style could be used by anyone. You didn’t need to inherit things — you could buy them in a thrift store or antique store. If they were a little broken, so much the better.

Dishes didn’t have to match, linens could be crumpled, with maybe a few holes in them. That was perfectly all right. The style was about the beauty of age, use, decay. It promised authenticity. Like the Velveteen Rabbit, things were more real if they had been used and loved.

It appealed to me at once because it was the style I had first known, in my grandmother’s apartment in Budapest. If you wanted to, you could call it Genteel Poverty, but that doesn’t quite have the same ring, does it? My grandmother had it down: the antique linens (because women in her family had embroidered them), the mismatched plates and glasses (because some in the set had broken), the furniture that was a little damaged (because repairing it would have cost too much). Shabby Chic is, of course, a romanticized version of that. But as you know, I’m not against romanticizing things. A human life without romance, without illusion, would not be much fun. Anyway, chic is an illusion. Just ask that consumate sorceress, Coco Chanel.

Ashwell lives in California, although she’s originally from England — her color palette was all wrong for me. But the underlying idea was just right. And it came just when I needed it, when I had very little money to spend on the basic necessities, much less decorating. But I love living in elegant spaces. It makes me feel happier and more human. So here was a decorating style that matched my history, my budget, my basic philosophy of life.

Since then, I’ve applied her philosophy to all sorts of things: the way I buy clothes and books, the way I cook food. I would paraphrase it this way: “I may be thrifty, but I’m determined to be elegant.” I try my best to be both . . .

I thought it would make sense, in this post, to include a few pictures of what my apartment looks like now. It’s in Boston, so I have New England light, which has an undertone of gray. You have to combat that with rich colors.

Let’s start with my living room widows. That table, I bought unfinished and refinished myself. The chairs are from an antique store, although I recovered the seats. The yellow armchair is from Goodwill, the Victorian slipper chair is from an antique store that was selling it cheaply because the fabric is so damaged. Until I have time to have it properly reupholstered, it’s covered with a piece of Waverly fabric in my favorite pattern. The lamp I bought in a hardward store and repainted, then added the shade. I sewed the bobble fringe on myself. And the small black table, I carried a mile from Goodwill to my apartment. It’s a little damaged, but works just fine, as you can see.

This chair in my hall was originally from Goodwill, and it was brown. I painted it, put a piece of fabric over the cushion (that’s another thing that needs to be reupholstered), and added a pillow, also from Goodwill. The small sewing chest contains jewelry, the shelf holds green Indonesian potter collected over many years, on doilies crocheted by my grandmother.

And here is the shelf with the pottery, taken after I had bought my one indulgence, a CD player. I’ve had the shelf for more than ten years, and it’s a little water-damaged. Someday, hopefully, I’ll have a chance to refinish it.

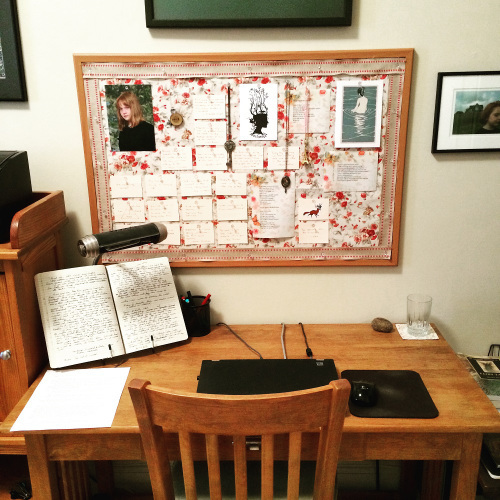

This is my writing desk. Both the desk and chair were bought unfinished, and I refinished them. Everything else came from various places: hardware stores, Staples, art stores where they sell picture frames. The bulletin board came from Staples, but I covered it in fabric and pinned ribbon around the edges.

Across from it is the chest of drawers, found in an antique store. The things on it are from various places, mostly antique and thrift stores, although that lovely mottled vase comes from Etsy. The silver mirror needs to be polished . . . To the left is a bookshelf that holds my murder mysteries. Because there are days when nothing is as satisfying as a good murder. And the painting is by my grandmother.

This is just a collection of cushions on the daybed, which serves as a sofa and a place for guests to sleep. The ones in the back are actually long pillows — I sewed the covers myself. All the other cushions come from discount stores, except the one with the flowers, which is from Goodwill. The scarf behind the daybed is also from Goodwill.

And this is probably the shabbiest but also chic-est thing I own: my bear Dani, who is almost my age. I painted that chair, and the shelf behind him still needs to be repainted — it’s supposed to be cream, not blue. But that will happen this summer, when I have some time.

Honestly, I think the reason I adopted this particular style, aside from its practicality (my dishes are cracked? that’s because they’re chic!) is that everything looks a little worn, which also means well-loved. It’s about having a life that is really, genuinely lived in. Which is of course what I try to do with my life — live in it as thoroughly as I can.

April 10, 2016

Glamour and the Struggle

I don’t remember who said it, except that it was a well-known writer. It flashed by one day as I was scrolling down my Twitter feed: “Don’t glamorize the struggle.” And I thought, yes, I know where that’s coming from. I understand that we should not glamorize the struggles of other people, or artists in general because they’re the ones who usually get glamorized. We should not say that poverty or addiction or mental illness make anyone a better or more authentic artist. And I agree with that.

But something in me rebelled just a little. It said, but if I didn’t glamorize my own struggle, where would I be? With just the struggle, that’s where. So what I want to say is, no, I would never glamorize anyone else’s struggle. But I do often see friends of mine who are writers and artists glamorizing their own struggles, and I think we’re allowed to do that. Because sometimes glamor is all we have, and while it doesn’t substitute for health insurance, it can in fact make the struggle easier to bear. We all get to have our own coping mechanisms, and glamor is one of mine.

What is glamor, anyway? I looked it up in the Oxford English Dictionary, where the first definition is as follows:

“Magic, enchantment, spell; esp. in the phrase to cast the glamour over one.”

The very first reference listed is to the old English ballad “Johnny Faa,” about a countess who runs away with the gypsies: “As soon as they saw her well far’d face, They coost the glamer o’er her.” That reference dates back to 1794, but of course the ballad itself is much older. Johnny Faa casts a glamor over the countess so that she runs away with him, from her castle and count.

In 1830, Sir Walter Scott used the term in that sense, writing, “This species of Witchcraft is well known in Scotland as the glamour, or deceptio visus, and was supposed to be a special attribute of the race of Gipsies.” Sorry, I know, the gypsies are often referred to this way in English and European literature, and yes, it’s had terrible consequences historically. It’s not usually good to be associated with magic, or its little sister, glamor. It often leads to imprisonment or hanging.

Why do I call glamor magic’s little sister? Here is the second definition listed by the OED:

“A magical or fictitious beauty attaching to any person or object; a delusive or alluring charm.”

Glamor carries the connotation of fakery: it’s fictitious, delusive. True magic is the art of changing: if you turn into a hawk by magic, you are a hawk. Glamor is the art of seeming. If you turn into a hawk by glamor, you still can’t fly. It’s a false magic, or at least a lesser magic.

When we glamorize the struggle, we make it seem less hard, but of course really it’s not, right? Although Alfred, Lord Tennyson does write the following lines in Idylls of the King, published in 1859:

“That maiden in the tale, Whom Gwydion made by glamour out of flowers.”

And that was a true glamor, because Blodeuwedd really was made, and became a true woman. So glamor does have some sort of power. To be honest, I think it has significant power because glamor alters our perceptions, and our perceptions do in large part determine our reality, especially the reality of our struggle. Glamor won’t get us health insurance, but it will change how we feel about our lives, whether we are optimistic or pessimistic about them. And for me, honestly, that makes a huge difference.

So when I feel most in the struggle, when I feel most down, most filled with self-doubt, that’s exactly when I tend to glamorize the most. That’s when I put on a long, swooshy skirt and walk through the city as though I owned it: yes, all the streets and the trees and the leaves that have fallen. That’s when I start to tell a story about myself in which I do, indeed, glamorize the struggle. I remind myself that although I did just spend five hours grading undergraduate papers, and I have five more hours to go, I’m still a writer — even if I haven’t touched my manuscript in a week. Because if I didn’t have that, what would I have? Just the struggle. And honestly, without the glamor, without believing in the magic, I might give up the struggle. It’s so much easier to have a quiet, sensible life than to be an artist.

I’m particularly interested in the etymology of the word. Here’s what the OED tells us:

“Etymology: Originally Scots, introduced into the literary language by Scott. A corrupt form of grammar n.; for the sense compare gramarye n. (and French grimoire ), and for the form glomery n.”

A corrupt form of grammar? Grammar, seriously? As in, “That department of the study of a language which deals with its inflexional forms or other means of indicating the relations of words in the sentence, and with the rules for employing these in accordance with established usage; usually including also the department which deals with the phonetic system of the language and the principles of its representation in writing. Often preceded by an adj. designating the language referred to, as in Latin, English, French grammar” (OED). That grammar?

In other words, glamor is related to writing. It’s a form of writing. A grimoire, you may remember, is “A magician’s manual for invoking demons, etc.” (OED). But the OED also says that it comes from the French grammaire, in other words, grammar. And gramarye is defined as either “Grammar; learning in general. Obs.” (OED) or ” Occult learning, magic, necromancy. Revived in literary use by Scott” (OED).

What do we learn from all this? Well first, that it’s all Scott’s fault. Which is a handy formula for pretty much anything: blame Sir Walter Scott. Second, that magic is and has always been intimately related to writing. To spell is both to create a word and to bespell, enchant. Writing is magic in that it alters our perception of realty, and so often perception is, let’s say, 70% of reality. (The other 70% is the part you can’t make go away, like hailstorms. But perception can change how you feel about hailstorms.) Third, that glamor is one of the tools of the writer, and I would say the artist in general. Glamor is actually the essence of what we do: we change not reality, but perception. We are spell-casters, all.

No wonder we glamorize the struggle.

I don’t have a clear answer as to whether or not we should. After all, Emily Dickinson’s and Vincent Van Gogh’s struggles were real and painful. And yet out of them came the most glorious art. What I do know is that I sometimes glamorize my own, and I think that’s all right. If I didn’t, I would be a lot less sane, and I would have a lot less fun. I wouldn’t walk through the city in a swooshy skirt, feeling like the heroine of my own novel, telling a story about myself as much as I tell a story about any of my other characters. I do think it’s important to be honest about the struggle, about how much sheer work goes into the making of art . . . which may or may not be good once you’re done. Which may or may not even be noticed. But it’s also all right, I think, to glamorize at least your own struggle every once in a while. If I didn’t, it would make the struggle so much more of a struggle, you see.

I chose this picture because it’s a very good example of glamorizing the struggle, taken on a day when I was tired and rather despondent because I’d been working so hard and not sleeping enough. After many hours of grading papers, I went out for some necessary grocery shopping and decide to take a short detour through the park. That’s where I took this picture, but as I’m sure you can tell, the underlying reality has been softened, sharpened, by an Instagram filter. And parts of the image have been cropped. The end result is me against dark the water of a forest pool, looking rather mysterious actually, when in reality I just looked tired. But the resulting picture makes me feel like a glamorous writer . . . which means I’m more likely to think of myself that way as well.

April 3, 2016

Creating Rituals

Almost every morning, I do the same thing: wake up, eat breakfast, and then exercise.

Breakfast is almost always the same. A bowl of oatmeal with raisins. A mug of tea with milk. A glass of half orange juice and half fizzy water. And then I exercise for twenty minutes: a combination of yoga, pilates, and stretching. Always the same, every day, although I vary the moves and the order in which I do them, so I’m using different muscles on different days. But that’s my routine, and it doesn’t often vary. It varies most often when I’m traveling, either for teaching or when I’m at a conference or convention. In that case, breakfast might be a cereal bar, but I’ll try to make it a relatively healthy one, and I’ll still do my exercises in a hotel room, going through at least the basic routine.

I have an evening ritual as well. It involves a bubble bath and some reading for pleasure (almost the only time I get to read for pleasure). I also have other rituals: making my bed in the morning, buying flowers each week. I suppose I have rituals of all sorts.

What I want to say in this particular blog post is that rituals are important, because rituals change you. I learned this specifically when I started exercising every day. I’d never been a particularly athletic person. When I was in high school, I was on the tennis team and gymnastics team, although I wasn’t particularly good at either. In college I took dance classes, and those were the most fun . . . I learned that I love to dance. So I took dance classes on and off, mostly ballet because that is one of my great loves. But honestly, I’d never exercised regularly, until one day I created a routine for myself. I would do it several times a week for about forty minutes, and always felt better when I did. At some point, I’m not even sure why, I started doing it every day, but I didn’t have forty minutes every day. I did have twenty minutes every day . . . So the ritual was born. And then something happened that taught me a lesson about the importance of rituals: my body changed. I became leaner, stronger, and more flexible. And eventually (it took several months), I was surprised to realized that I was in the best shape I’d been in my entire life: better than as a teenager, or in my twenties, or thirties.

I know, you’re probably thinking: well, that’s obvious. If you do something every single day, it changes you. But the realization hit me like a hammer (ouch.) I had somehow assumed it was one of those platitudes: you know, the sort of thing you pin up on a bulletin board for inspiration that isn’t actually true. But it’s true. Rituals change you.

They can change you physically, and they can also change your inward perception of yourself. Making my bed every day, buying myself flowers every week, are ways of telling myself that I care about my space, that I take care of myself. They are the outward signs of my own self-care.

The best thing about rituals is that once they’re ingrained, you do them automatically, and it feels wrong to neglect the ritual — when I don’t exercise, it feels as though the world is somehow unbalanced, or I’m unbalanced. I never go more than a day without it. It’s easier to go through the ritual than not, I suppose because we are such creatures of habit. So it matters what kind of habits we develop.

What I’ve tried to do, since learning this lesson, is create productive rituals.

Creating a ritual is not easy. Here’s how you do it:

1. Figure out what the ritual is. Is it to exercise every day? Figure out when you’re going to do it, what specific exercises to do. Put together the routine.

2. Make it as easy as possible. It should take the minimum possible effort to follow the ritual. For example, I exercise right after breakfast, in my pajamas. My pajamas look and feel like yoga clothes. The music is right by the CD player, just waiting for me. Once I’m done, I shower.

3. Do it every day, or at whatever regular interval you’ve decided — once a week, once a month, but honestly I think daily rituals are the strongest. If you miss a day, forgive yourself but do it the next day. Keep trying, keep doing it. Eventually, habit will kick in and the routine will click. When you’ve done it enough, it will become a ritual. At that point, it will be easier to follow the ritual than not.

4. Make sure the ritual is a healthy one, because we can ritualize anything, we human beings. We are such creatures of habit, like animals that walk through a field following the same path every day. If your ritual is to sit in front of the television eating ice cream every night, that ritual will be very hard to stop. Indeed, the best way is not to try and stop, but to create a new ritual.

Does all of this sound terribly boring — exercising every day, eating the same breakfast every day? I don’t find it so. Instead, I find it reassuring. Going through the ritual every morning grounds me, particularly when I’m traveling — when I’m doing so much, speaking to students or an audience, it’s good to have taken the time, first thing in the morning, to go through my personal routine. It was something I did that day for myself. And having rituals frees me up to think about other things — it’s as though I’ve set part of my life on autopilot so I can think about other parts of it more deeply, live those other parts more fully.

So that’s it, really. That’s what I know about rituals, except that as I wrote above, we human beings are creatures of ritual. Think about our religions. We are continually creating rituals for ourselves. Make sure yours are good ones.

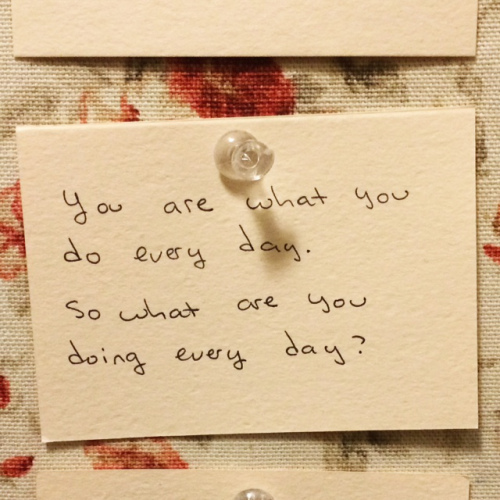

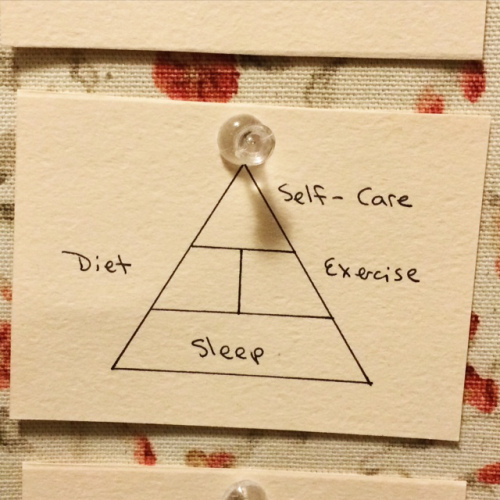

I do, in fact, have inspirational quotations pinned to my bulletin board. Here are two of them:

(Now I just need a ritual for the sleep part . . .)

March 28, 2016

You Lovely People

Oh, you lovely people.

I see you, every day, online and offline. I see you writing books and planting gardens and taking care of children. I see you painting murals and inking comics. You are playing the guitar or a piano. You are taking a ballet class, or learning to tango. You are making breakfast.

You are doing it with hope and grace, and faith in things we don’t know to be true: that tomorrow will come, that the things you are doing are worth doing. What you are doing is both elegant and ordinary, because the ordinary is, when done well, true elegance. And it is extraordinary, because any act of creation is extraordinary. It shows a love of life.

Meanwhile, I see terrible things. Bombs in parks where children are playing. Planes going down filled with teachers and doctors and electricians. With people who a moment ago were watching a romantic comedy.

And yet you are still teaching and doctoring and installing electrical systems. You are still planning and planting parks. You are still making romantic comedies, because love is inherently funny.

I see you and you see each other: all of us, all over the world, doing the work that matters. The work of creation.

I see your spring flowers, and the cakes you baked that didn’t quite turn out right. I see your new outfits. You are celebrating, because you are alive, and that in itself is cause for celebration. You are seeing the world, and it is beautiful, and you are doing your best to save it, whether you are trying to change laws, or sending money to organizations, or lifting a caterpillar off the sidewalk.

And you are noticing it, seeing the world, which is another way for nature to admire herself, because aren’t we her eyes? And aren’t we here in part to see her, to admire her beauty? We are her mirrors. We show her the hawk swooping between city buildings, the cherry blossoms in bloom. Ducks sliding across the water, willows bending like cathedral arches.

You are participating in a great dance.

You are a thread in the most magnificent tapestry ever woven.

You are a note in the song the universe is singing.

You are lovely, and this is what I was thinking as I watched you, all of you, simply being yourselves.

March 13, 2016

The Work of Writing

I keep reading blog posts that basically all make the same point: anyone can find time to write. You’ve probably read them too. The message is, if you want to be a writer, you can find the time. Get up early and write before work. Write on your lunch break. Write on your commute home. Write after everyone else is asleep. If you can write even a hundred words a day, eventually you’ll have a novel.

It’s not a bad message, but it’s aimed toward aspiring writers. And aspiring writers, I would argue, are very different from working writers, who are different, again, from professional writers.

Let me clarify what I mean by those terms. An aspiring writer wants to someday be a writer. He or she has not published anything yet, but is working on it, actively, ardently. Or has published a few things, and is working on publishing more, and more steadily. Most of my MFA students are in that position. A working writer is someone who actually works as a writer, by which I mean writes for money. That money makes up a percentage of his or her income. He or she had to pay taxes on it, which gives him or her headaches. He or she probably has an agent and an accountant, partly to lessen those headaches. But the working writer is not yet a professional writer. The professional writer makes his or her living writing.

Being a professional writer is very, very difficult. I have friends who do it. It’s much easier when you’ve already written a lot of books, at least some of them have been bestsellers, and at least some of them have resulted in movie or television deals. The economics of writing are just too hard: they are stacked against the writer. Anyone who has made it as a professional writer had put in a lot of hard work, and had a lot of lucky breaks. He or she should be commended. Getting to that point is so difficult that writers are told, over and over, often by their own agents, “Don’t quit your day job.” There are no guarantees that you will succeed, and once you do, there are no guarantees that you will continue to do so. I’ve seen writers trying to make it professionally fall behind on rent or put off buying medicine for chronic illnesses because an advance didn’t arrive when it was supposed to.

So what does it mean to be a working writer, which is where I would put myself? February and March have been a particularly busy period for me. Here are the things I’ve had due: First and most importantly, a revision of my novel in response to my editor’s letter and comments. I’m almost done with that. Then, page proofs for a short story that will appear in an anthology, responses to copyedits for a short story that will appear online, an interview for a short story reprint, and page proofs for three poems that will appear in various venues. I’ve had to write three new things: a review of an academic books (done), a conference paper (almost done), an introduction to a short story collection (working on it). Oh, and I had Boskone, where I appeared on panels, gave a reading, met with other writers and my agent. Next weekend, I will have the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, where I’m giving that paper. I also have to count in there responding to various writing- and publishing-related emails, and sending a panicked email to my accountant because I haven’t even started working on taxes yet. (Although it won’t be too hard, since I’ve already paid estimated taxes for 2015, which means my documents are mostly in order).

Notice that not a single one of those things involves writing several hundred words a day early in the morning, or on my lunch break, or commute, or whatever. And in case it’s not clear, at the same time I’ve been working — teaching classes.

How do I do it? First, I’m very lucky in that my job is more flexible than most. I put in a solid 40-hour week, but I can decide when to put in most (though certainly not all) of those hours. Second, I do the writing work whenever I can. I fill every nook and cranny with it. What I’ve learned is that I’m not happy unless I’m also doing new writing, so amid all of that, I wrote a story. It still needs to be revised, and hopefully I can do that later this month. It’s taken me three months to write, which feels like a very long time for an 8000-word story. But in the meantime, I’ve revised a 100,000-word novel, so there’s that.

By the time you’re a working writer, you’ve already made a commitment to writing as a job, usually a second or third job. That means you have deadlines to meet, people to communicate with, just as you do in any job. It’s no longer just sitting in your bedroom, or in a café, or on a commuter train, and writing. It means you’ve already made a series of choices: for example, I have no idea what the hot new television shows are. I would have no time to follow them. Granted, these two months have been exceptionally busy — it should not be like this all the time, or honestly, I’ll just collapse. You need to get your sleep, you need to make sure you’re still exercising, just as you do with any job. You need to make sure you’re still living, or will go back to living a slightly more normal life as soon as things are less busy. Because a writing career is not a sprint, it’s not even a marathon: it’s just running. One day you decide to start running, and then you keep going. Only people who enjoy the actual running, and are not particularly invested on finish lines, have long-term writing careers. People who want a ribbon or trophy give up quickly.

Will I ever be a professional writer? Maybe someday. I’m certainly not counting on it, and it’s always a good idea to have a day job that you like — or love, because I genuinely love teaching. Maybe in twenty years or so I’ll retire, and by that time I’ll have enough books published that I can work as a professional writer!

My message here isn’t all that different from those blog posts I mentioned: Yes, if you’re an aspiring writer, find time to write, sit down and write, do it if not every day, then as often and regularly as possible. But if you’re lucky and work hard, you will one day transition to being a working writer, and that will take different organizational skills, as well as a particularly intense level of commitment. (You may as well start working on the commitment now.) From over here, I can tell you that I love being a working writer, despite the fact that I often don’t get enough sleep. (I need to work on the sleep — seriously, I can’t stress the importance of making sure you’re not going through the day delirious and hallucinating.) Even when I’ve spend five straight hours, butt in chair, working through copyedits made with Track Changes, which I can tell you is my least favorite activity in the world that doesn’t include actual physical pain. Even then, I love what I’m doing.

And that’s the secret, in the end. You have to love it for its own sake, whether you are an aspiring, working, or professional writer. That’s what we all share in common.

(This is me, on the day I was doing copyedits. Blurry picture, mirror could use a cleaning, and I’m in old jeans and socks. Yup, that’s what it looks like.)

March 6, 2016

Victorian Virtues

Recently, I bought boot polish.

You’d think I would be the sort of person who has boot polish. I mean, I have silver polish. I have dusting cloths. I have an entire sewing box, with a button collection. Remember button collections? Our mothers and grandmothers used to have them, and we used to take them out, look at the buttons, wonder where that one button shaped like a ladybug had come from. We used to let the buttons pour through our hands. I even have a tool box, with a hammer and different types of screwdrivers, so this isn’t about having the domestic tools associated with one gender rather than the other. I just, for some reason, didn’t happen to have boot polish. I don’t know why.

But my boots were looking positively disreputable. In Boston, when it snows the city maintenance workers spread a great deal of salt around. This winter, we’ve had very little snow. At this point it’s all melted, but the other day, while I was walking to the library, I kept seeing white piles. I thought, perhaps it hasn’t all melted yet? And then I realized they were piles of salt. That salt gets on your boots and leaves a white crust, as though the tide had come in and then gone out again — you have a tidal mark on your boots. And that’s how my boots looked: as though I had walked, or rather treked, through a frozen sea. So I went to the drug store, where there is a shoe care section, and bought black boot polish, several different kinds of brushes, and a buffing cloth. Now I have a boot and shoe care kit. As I sat there, on the kitchen floor (with some paper towels down to protect the floor from polish), polishing and buffing my boots, I felt a sense of virtue, and I thought, yes . . . this is what I always read about in Victorian novels. It’s the virtue of careful maintenance.

I don’t remember where I read this story, but it’s about a Victorian man who chose his wife by the neatness of her boot heels. What in the world? you may ask. But, as the storyteller explained, boot heels are constantly wearing down, and if you let them, worn, uneven boot heels will eventually ruin the boot itself. If you maintain the heels, the boots will be wearable for . . . well, a lifetime, but in the case of many Victorian boots it’s really several generations, since they’re so well-made. In a day when boots were much more expensive, relative to the average income, than they are now, boot maintenance, including boot-heel maintenance, was essential. It was the sort of thing that distinguished the thrifty, careful housewife from the other kind.

Nowadays, I often look at the boots left at Goodwill, some of them boots that originally cost several hundred dollars, and what I notice is that there’s nothing at all wrong with the boots. They simply have worn-out heels. Getting heels replaced isn’t cheap. It’s even more expensive if you need to have soles replaced as well, as I did recently: about $45. But that’s still less expensive than buying a good pair of boots. Polishing isn’t as important as getting heels replaced, but it’s part of maintenance. The maintenance of a household and wardrobe also includes polishing silver, dusting bookshelves, sewing on buttons. But these are all Victorian virtues. They seem so old-fashioned now that it’s almost as though they’ve been forgotten. When buttons fall off, people get rid of the garment.

The criticism of these virtues is that they seem so small, so petty. They take time, and often that time is gendered, because it’s usually women who do the dusting, who sew on the buttons or sew up the hems. Women are usually the ones responsible for maintenance and small repairs, although I think it’s still more common for men to polish shoes, partly because men’s shoes are so much more expensive. And yet I want to argue for these sorts of virtues, first because they are part of a culture of care that we seem almost to have forgotten — once, you cared for your things, rather than discarding them when they broke or tore or fell out of fashion. That led to a lot less waste. So these small virtues have larger implications for how we use our stuff, how we related to the larger world around us. Second, I think they’re good for us personally. Caring for your things changes you — polishing boots changes you, polishing silver changes you, sewing on buttons changes you. It makes you a different kind of person, a slower person in some ways, a person who takes time. It makes you feel differently inside, both about the stuff you’re caring for (because maintenance is a mark of love) and about yourself. Third and finally, they lead to beauty and elegance. My boots were a whole lot more beautiful once they were polished. I was proud of how they shone. I wore them proudly, rather than cringing with embarrassment whenever I put them on. I felt that particular satisfaction you feel when everything is in the right place. Now, there’s no reason everyone should eat with silverware, rather than stainless steel. But I love it, and the truth is that it’s cheap if you buy good, old silver plate, and it’s easier to take care of than you would think. I love the sheen of it, less hard than steel, sort of like moonlight.

I’m very proud, now, of having all the right tools to polish my boots. And to sew on buttons. And to do the sort of small maintenance work we all need to do in our lives, which makes our lives better, easier, more beautiful. So, you know, if you haven’t polished your boots and shoes in a while, this is just something to think about. There is, still, some value in those old, and seemingly old-fashioned, Victorian virtues . . .

(The painting is Sunlight and Shadow by William Kay Blacklock. Yes, I know, it’s a romanticized image of a woman sewing! No, I did not look like this while I was sitting on the kitchen floor, polishing my boots. But it still captures perfectly the beauty I associate with small Victorian virtues.)

February 23, 2016

The Overwhelm

I’m feeling a bit overwhelmed.

By the time I get to Thursday, I will have spent an entire two weeks without a single day to myself. There are all sorts of reasons for that, mostly teaching (I’ve been holding student conferences, which sometimes means meeting with students for five hours a day) and Boskone, which was a wonderful convention but also exhausting. I have all sorts of things I need to get done, most of them by the end of the month, and I’m simply overwhelmed with work. I suppose the good thing is that it’s work I want to do: teaching and writing, mostly. But that doesn’t help much when you’re feeling the overwhelm.

That’s what I call it, the overwhelm. It feels like a place I’m in the middle of, as well as a state of mind. It’s a place where I haven’t gotten enough sleep in a long time, and so I’m tired and a bit despondent, and wondering why I’m doing any of this anyway. It’s a place where I doubt myself.

It’s a place where I don’t want to talk to people anymore. Where I just want to curl up in bed, eat almonds and chocolate, and read murder mysteries. Or watch Murder, She Wrote, one episode after another. Anything having to do with people killing other people, and then a clever detective (preferably female) figuring out how and why. I suppose it’s a misanthropic impulse, as well as a sign of empathetic burnout. The last thing I want to do is feel anymore. I want clean, clear rationality, a sifting of clues.

But of course I can’t do that. Tonight I have to prepare for class tomorrow, and I have emails to send. People people people — it’s all about people, isn’t it? It’s all making contact, either in person or electronically. And the truth is that I love people — I find them fascinating. If I didn’t, I couldn’t be a writer. I love teaching: my students are smart and interesting and funny (sometimes unintentionally so), my graduate students are brilliant. But people are overwhelming, for an introvert.

I’ve been an introvert since I was a child. When I was a teenager, I use to have a fantasy: that I could go away and live in the forest, in a castle, and be a sorceress. That would be my job description, sorceress. I would have a magical mirror, in which I could see whatever was happening, all over the world. But I wouldn’t have to participate. I could just stay in my castle . . . I suppose it’s a classic fantasy, for an introvert.

Sometimes I wish I could just write — live in a small house in the forest and write books, stories, poems. That’s the more realistic version of being a sorceress and living in a castle, I suppose. I would still have the internet: that would be my magic mirror. I could watch the world. But I know people who’ve done that, just written, and it’s very, very hard. Hard to eat, hard to pay rent. Not many of us have the luxury of cutting ourselves off from the world.

So what should I do? The only thing to do, really, is to become the forest, become the castle. To do what I have to, participate to the extent I must, but create a space within myself where I can be calm, where I can rest. Where I’m not so worried about getting up, getting where I need to go, that I set two alarm clocks in the morning. I mean, I still need to do that in real life. But there must be an imaginary life I can create where it’s not necessary. And I do have to get to Thursday, when hopefully I can rest just a little, before I start the mad scramble of trying to catch up.

Sometimes I think life shouldn’t be quite so overwhelming, but that’s what happens when you want to be a teacher and a writer. If I were trying to do less, it would all be easier, so really I have only myself to blame. Still, it’s a hard place to be, the overwhelm. Especially when you can’t see when you’re going to get out of it. (Thursday, I tell myself. On Thursday, I’ll get some rest.)

The truth is that I didn’t even want to write this, because that’s more communication, with more people (although you are lovely people, who read this). But I haven’t written a blog post for a while (and this is why), so I thought I should. And also, it’s good sometimes to talk about the things that aren’t working, that aren’t the way you want them to be. I want to do everything I’m doing, but I don’t want to be overwhelmed by it, and I want more than five hours of sleep a night, and I want to be able to do laundry, and shop for groceries. I want to write new stories . . .

This is what it feels like, in the overwhelm. It feels exhausting, and anxious, and filled with doubt. Will I ever be the writer I want to be? Will I ever be able to do the things I want to?

And then, because I’m a big girl, I look at my to-do list and think, one step at a time. Do the things, cross them off, it will get done. Have dinner, rest for a little while, get back to it. Sometimes you just have to keep your head down and do the work. That’s what it’s like in the overwhelm, but there is another side. I remember what it was like, that summer I went to Budapest and lived alone for six weeks, and wandered around the city, and took Hungarian classes. I remember being blissfully happy, waking up in the morning to birdsong in the park and sunlight through the windows. That exists, and I’ll get back there. In the meantime, I’m going to do the work, hoping it will get me to my goals. As, honestly, even writing this blog post has.

(This is future me in my castle in the forest. I have invisible gardeners, because of course I do. The illustration is by Charles Robinson.)

January 24, 2016

Keeping It Real

Recently, I was looking at another writer’s biography and noticed that he had attended all sorts of prestigious writing residencies. And I thought, wait, am I supposed to be applying for those? Maybe I should be applying for residencies and grants . . . After all, they look good on your CV. Don’t they?

I had to remind myself to keep it real.

Here’s real: What is the purpose of residencies? They give you places to write. I already have a place to write: my home office is where I write everything, and the most comfortable writing place I know. What is the purpose of grants? To give you money so you can write. But since I teach more than full-time, the chance that a grant will replace my income, much less my benefits, is very small. So what residencies and grants would really give me, right now, are . . . a line on my CV. A reference in my biography. And that’s not enough.

I have to think about what is real because at one time, I went wrong . . . I made decisions based on prestige, on how the world would evaluate me. That was when I ended up at Harvard Law School. It was my last year of college, and I wanted to go on to a PhD program, specifically to study English literature. But my family discouraged me, so I applied to law school instead. I got into Harvard, so that seemed the obvious choice . . . I mean, Harvard Law is sort of like getting the world on a platter, right? Or so many people believe. The reality is that you’re never handed the world on a platter. I spent four mostly miserable years in law school, and three mostly miserable years working as a lawyer. Don’t get me wrong — I have a great deal of respect for good lawyers. I hope I was one of them. But it wasn’t for me because what was real, the deep underlying reality of my life, was wanting to write. I had wanted to write since I was a child. Instead, I was revising corporate contracts until 2 a.m. And I was deeply in educational debt.

So I paid off my law school loans (all of them, in three years, because I knew that otherwise I would die inside — and I had paid for law school entirely by myself, so they were exorbitant). I applied to graduate school. Then, I had to face the question of what was real again because I got into Boston University as well as several universities that were more prestigious, that were Ivies. But Boston University was the only one that would both pay for my tuition and provide me with a stipend I could live on. Was it worth taking on educational debt again for an Ivy League university on my CV? I actually had to think about that for a while. But in the end I decided that no, it wasn’t worth it. What was real, in this situation, would be the education I was getting, the focus on literature, the time to write.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten better at distinguishing what is real from what is not — or perhaps what is simply less real, less important. Real are the stories I write, the books I publish. Not a prestigious residency or grant, unless it leads directly to more stories, better books. Real is money for food and shelter. Real is raising my daughter. Real is having lovely things around me.

Hunger and cold are real. Fear and failure are not — they are just the way my mind perceives reality. But they are interpretations, not facts. Joy, on the other hand, is real. (Why joy and not fear? Because I usually realize that my fear is a misinterpretation of the world, whereas my joy rarely is. Joy leads me right most of the time. Fear, rarely. Although if I were to encounter a ravenous bear, then yes, my fear would be real, and I would listen to it.) Literary prizes are real if they result in more people reading my books, or represent people I respect recognizing my work. Those are real, but the important things are the quality of my work and the extent to which I am able to reach out, speak to people through my writing. Those are the things I need to focus on.

I’ve been online long enough to realized that most internet controversies are not real. They do not change any minds, and have no tangible result in the world of actual things. Real requires substance behind the appearance (which is why fear of ravenous bears is real, when there are actual ravenous bears in the vicinity).

I hope all of this makes sense? I feel as though I’m trying to describe something rather nebulous in words, which are concrete. But what I ask myself, over and over in my life, is this:

What is real?

Because I’m tempted by the unreal as much as anyone — by prestige, by what I’m supposed to be doing. According to whom? I’m not sure, probably the invisible audience we all create in our heads of people who are judging us. Don’t you do that? Don’t you imagine an audience of people who don’t even know you, judging you for your failures? Our imaginary audiences can be harsher than any actual people . . .

So I bring myself back again and again to that question, every time someone asks me to do something or I create a new project for myself. Am I doing this because it will have some real effect, because it’s something I actually want to do? Or am I doing it because it will look good in my biography? What is real to me, what do I truly care about, what will actually change my life or perhaps myself?

I’m a fan of Mari Kondo, the Japanese neatness guru. I try to follow her injunction to only keep those things that truly give me joy. (Although I have a lot of those things — my life is definitely not minimalist.) I’ve even folded my clothes the way she suggests . . . But I think that message should be applied not only to how we organize our stuff, but also how we organize our time. What is real, what sparks joy? Some things that are real may not spark joy, certainly not all the time — if you’re working at a job you dislike because you need to pay off your educational loans, then you may not get a lot of daily joy from it. But you will at least have the satisfaction of knowing those loans are going away, month by month. (For a while, my greatest sense of joy was in looking at my diminishing loan balance.) That sense of accomplishment is real — it is a thing that exists and is important.

Sometimes I practice distinguishing what is real, because our culture makes it so difficult to tell the difference. It sells us substances that are not real food. It tells us companies are worth a billion dollars based on stock valuations that are going to change tomorrow. It praises celebrities who are famous for being famous, without actual accomplishments.

Do this: find the real, underneath. If you’re standing on that, I find, you’re standing on solid ground. You have a sense of stability, a sense that you know what’s what. When I lose that sense, when I’m not sure where I’m going and the world seems to be spinning out of control, I think, what is real right now? Lunch. Papers to grade. The fact that I have a warm jacket, so I will not be cold when I go outside, although it’s snowing. And there’s comfort and joy in that solidity.

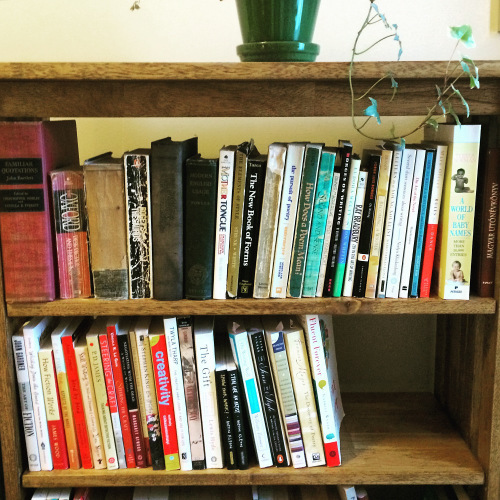

These are two pictures from my office. First, a quotation pinned to the corkboard above my desk . . .

And second, my writing books — the ones I’ve found most valuable and reread periodically.

January 17, 2016

Stasis and Stability

It feels strange to be where I am now: for the first time in, well, ever, my life feels stable. Oh, I know that could change tomorrow. I’ve gone through so much instability in my life that stability actually worries me . . . I start wondering if I’ve fallen into a period of stasis.

My childhood was marked by constant moving. Before I started third grade, I had lived in four countries and spoken three languages. After that, it was one country and one language, but the longest I ever went to a single school was three years. We just kept moving . . . Then college, then law school, then working as a lawyer for three years, then graduate school . . . I was always either moving or working towards — something else. I was never someplace I could stay. There was never a sense of home.

Now I’m in a place where I could stay, theoretically, for the next twenty years, and honestly it’s a little scary. I have a stable academic position, I teach writing in two places I love — to both undergraduates and graduate students. And I’m writing. I have a novel contract — for two novels, in fact! I have deadlines. Honestly, I’m doing more work than I’ve ever done before in my life, but it’s the work I wanted to do. And I could just keep doing it. This is what I was working towards, all those other years, the unstable ones.

So what now? Because the truth is that I don’t want to fall into stasis, to simply keep doing what I’m doing. What I want is to use this stability as a platform. First and foremost, to keep writing. I have so many ideas, so many things I want to write about. So many projects I haven’t even started tackling yet. And as I said, I have two books coming out: one in 2017 that I’m going to be editing in the next few months and one in 2018 that I still have to mostly write . . .

So I think there are several lessons for me here:

1. Most importantly, stability could change. I know this, know it deeply in my bones. I have cancer in my family, so I know perfectly well that one medical diagnosis can change everything. And I know that anyway, time’s passing. I have a limited amount of time on this earth — none of us knows how limited our time is. So I need to do what I want to get done, not with a sense of panic, but with a sense of purpose.

2. Second, stability is not stasis if you use it wisely. Stability can be where, rather than being blown about by events, you sit down, ask yourself what you want to accomplish, and then accomplish it. And that’s what I need to do . . . the accomplishing part, since I already have a list of the things I want to accomplish. It’s on my cork board, above my desk. It’s not a long list, but it includes items like my goals as a writer.

3. Third and finally, be grateful. I’ve had so little stability in my life that when it came, it felt almost frightening. I had to keep reminding myself that this was a good thing. That this was a place where I could, for the first time, be truly productive.

Once, I read an article about the Hungarian writer Imre Kertész, who won the Nobel Prize. For years, he had worked as a translator, living in a small apartment in Budapest with his wife. He talked about having chosen that life deliberately so nothing would distract him from his writing. He had chosen a life of as much stability as he could, a life that did not require him to earn a great deal of money, a life that would support him just enough so he could write. So he could bring the images in his head into being. I’ve thought about that article ever since. It’s so easy for me to get distracted — this is a very distracting world we live in. But right now, right here, I have all the things I need. A lovely, warm home. Work that supports me — a lot of work, but not so much that it takes absolutely all my time (although some weeks it feels as though it does). Time to write, if I organize my time well enough, and if I have the calm, centered focus I need to do it. That focus is learned, not something that just happens — it’s something I need to create.

So here’s the plan: I’m going to teach, because that’s my job. And I’m going to write, because that’s what I’ve wanted to do just about all my life. In the past, I fit writing in around the instability, and still got a lot done. But it’s only recently that I’ve been able to write anything long, like a novel. Before, writing was always competing with things like, you know, graduate school. And surviving . . . Now I’m not just surviving. I have food in the refrigerator, heating in my apartment, and money in my savings account. (That last one — honestly, I wasn’t sure I’d ever get there!) So it’s time for me to produce.

To be perfectly honest, I feel deep in my bones that where I am now is not where I’ll always be. But the next step, whatever it’s going to be, is something I have to create for myself. So that’s what I’m going to do.

The photographs below are from Christmas Day, when I went to a bird sanctuary and wildlife refuge in Concord, Massachusetts. It was so peaceful there. And I thought about all these issues, about how stability was a good thing. It wasn’t necessarily stasis, or stagnation. Although really if you think about it, what is stagnation? A stagnant pool is absolutely filled with life, at the microscopic level. The fact that we can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there. The fact that we can’t see how what we are doing now is creating our future doesn’t mean it’s not being build, deep underneath, underground in our selves and souls. What we build there during times of stasis often creates the changes in our lives.

It’s as though we are winter forests. We may see dead leaves, bare branches. But the life is all underground, just waiting.

December 26, 2015

Guilt and Shame for Writers

I’ve been thinking about this issue a lot.

Several days ago, I posted the following:

1. Guilt and shame are the enemies of the artist.

2. Guilt is when you feel as though your time should be spent doing something else, for someone else.

3. Shame is when you think what you’re producing is not good enough, or you’re not good enough as an artist.

4. The only way to deal with guilt and shame is to feel them, because you’re going to feel them. Then do, and show, the art anyway.

I have to deal with guilt and shame all the time. I think most artists do. Guilt and shame are two different things, so I’m going to try to define them. But they’re similar in that they’re equally debilitating. And equally difficult not to feel — I think they afflict most of us who are trying to do creative work.

Guilt is focused inward and has to do with a sense of what you should be doing that is not art, and who you should be doing it for. I have a daughter; time I spend writing is time I don’t spend with her. I have a sense of duty as her mother, but of course I have a lot more than that — I want to spend as much time with her as I can, because time passes quickly and I know she’s growing up. Every experience we have together, even if it involves sitting on the sofa watching a movie, is precious. And I have students, a lot of them. I have a sense of duty towards them, and also toward the university programs that employ me — but beyond that, I want them to learn and succeed. Time I spend writing is time I don’t spend grading their papers, creating lessons plans. Would I be a better mother and teacher if I didn’t write? I don’t know. I’m sure I would have more time . . .

So that’s guilt: the continual sense that you should be doing something else, for someone else. The sense that writing is an indulgence, and your duty lies elsewhere.

Shame is different: it’s a sense about the work itself, that it’s not good enough, will never be good enough — for others. Shame has to do with how other people perceive you. If you never showed your work to anyone, you would not have a sense of shame about it. You might have a sense of failure, but it would be a private failure. You would feel relief — at least no one has to see how I failed!

Shortly after I posted about guilt and shame, I also posted the following:

Everything I write is a failure in some way. It never lives up to my original idea of it.

I think that’s true for so many writers. You have the story in your head, which you’re convinced is going to be the best one you’ve every written. And by the time it gets onto the page, it’s a flawed, awkward thing, like a young falcon, wet, tousled, squawking for worms. And you think, what happened to my original perfect conception? All the words are wrong. Even the commas are wrong . . . By that point, you’re convinced it’s the worst story you’ve ever written, and your writing career, such as it was, is over.

The more you write, the more you realize that this is a cycle, that it happens every time. Months later, particularly if you see the story in print, you’ll think — it’s not that bad after all. Not perfect certainly, but not the worst I’ve ever written either. But understanding that it’s a cycle and actually getting rid of the shame are different things — understanding happens in the conscious mind, whereas the sense of shame lies much deeper, in the unconscious. Understanding simply brings it to consciousness, helps you talk to yourself about it. The shame itself doesn’t go away.

At least I’ve found this is the case for most writers. It seems to me that there are writers without that sense of shame, who are confident in their own writing (although how would I know, since I don’t inhabit their heads). They tend to be writers who were encouraged by their families and teachers from a young age. The rest of us, particularly if we were discouraged at some point, have internalized a sort of societal voice. It says both that the work is not good enough and that you, as a writer, probably as a person, are not good enough.

And then it becomes not about the work, but about you: I must not be good enough, I must not be smart and skilled and dedicated enough, to be the writer I imagine I could be.

Therefore, says guilt, you’re wasting time. You really should be doing something else: volunteering at the local food pantry, supporting a political cause you believe in. Serving on the PTA. Don’t get me wrong, those are all good activities. But guilt says, you should do them instead of your art. Because, adds shame, your art is worthless.

If this were a self-help article, this is the point at which I would tell you how to defeat guilt and shame, as though they could be removed like an appendix. It’s not that easy. I’m pretty sure guilt and shame are here to stay.

All I can tell you is what I do. The first step is understanding what they are, and how they’re stopping you. And then, since they’re different, approach them differently.

Guilt: If you have the something inside you that makes you a writer, or a painter, or a musician, it’s like an itch. I find myself writing all the time, whenever I have free time. For fun, because that’s what I enjoy doing. When I can’t write, it’s like an itch in the middle of my back that I can’t scratch. Or worse, because I start getting tangled up inside. It’s as though writing untangles me. What I believe is that if you have that particular itch, something put it in you — call it what you will, but you were created with a purpose, and it’s that purpose, unfulfilled, that causes the itch, that makes you want to scratch at it, almost desperately. You were make to create whatever you have the impulse to create, and your unhappiness when you’re not creating is it the universe itself speaking to you, saying: hey, you’re ignoring me.

So yes, you have a duty to your family, to your students. But you also have a duty to yourself, and to something greater than yourself — to the work itself that wants to be created through you, and to the creative power of the universe that is trying to find a means of expression and has chosen you for it. If you ignore that duty for all the others, you will end up unhappy, unfulfilled. If you’re anything like me, you’ll probably end up feeling guilty for a whole new reason . . . now you’ve failed in your duty in another way, to yourself and God or whatever! But at least you’ll be able to see that these are competing duties, and that sometimes your parenting or teaching need to come first, but at other times your writing needs to come first. And then, maybe, you can start to negotiate among them.

Shame: The only way I know to deal with shame is a form of behavioral therapy in which you do exactly what you’re afraid of. And if you don’t die, then you know that you probably won’t die . . . the next time you receive a rejection, or moderate a panel, or do a reading. It’s not fun, but it works. Whatever you’re afraid of the world seeing you do, do that. Every time I publish a piece of writing, I feel a sense of shame, because as I pointed out, everything I write is a failure. I think, this isn’t good enough to show the world. (It seemed so good after I finished writing it, but by the time I’ve revised it and I’m fixing commas, I realize that I can’t even punctuate properly, so what made me think I could be a writer?) That’s one of the reasons I keep writing and sending out the work — because it’s scary. And it’s partly why I write this blog, because who am I to offer advice, to tell anyone my views on life, the universe, or anything?

But many of you, in your kindness, tell me that what I write resonates: that you feel and see it too. And I’m betting that many of you, if you’re writers or artists, or maybe if you’re just human beings, will relate to what I’ve written above. Which is perhaps the final way to deal with guilt and shame, and equally applicable to both. Realize that aside from a fortunate few (and we’re not even sure of them), we all feel guilt and shame. We’re all in this together.

(I thought this would be the most appropriate picture for this particular post: it’s of me first thing in the morning, before I’ve washed my face or even brushed my hair. In exceptionally good light, but otherwise, as the universe made me, whatever idea it had in its head at the time. About to eat breakfast . . .)