Theodora Goss's Blog, page 12

December 13, 2015

The Joy of Poetry

I’ve been writing poetry for as long as I can remember.

The earliest poems of mine that I still have are from high school. That’s when I started writing seriously, on scraps of paper, whatever I had on hand, and then recopying my poems into a large green notebook. That’s also when I started submitting poems for publication in the school literary journal. I think it was junior year that I won my first poetry prize, for a poem on Icarus. It was published in the literary journal and illustrated by another student. I was so proud . . .

Why does a child start writing poetry? I think it’s natural for us to love poetry: after all, the first literature we’re introduced to is poetry, in the form of nursery rhymes. We clap our hands to poetry, jump rope to poetry. The difference between “Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does your garden grow?” and John Keats’ “Ode to Autumn” is a difference in level of complexity, not fundamentally in kind. We love poetry naturally, and then we are taught out of that love, usually in school. I’m not sure how it happens. I think it starts with having to analyze poetry, to pick it apart for meaning and structure rather than letting it sing in our heads. It also comes from being taught, at the school level, only poetry that is somehow socially relevant: we are taught poetry with a political message because it’s easier to teach. The teacher doesn’t have to deal with the poetry-ness of it at all: it can be taught as social commentary that just happens to rhyme or have an underlying rhythm. Those of us who continue with poetry often belong to a particular sub-category of the high-school nerd, the literary magazine nerd — closely related to the theater nerd, and often found at the same parties.

I belonged to that category in high school. I was in theater, I wrote poetry. You could tell the literary magazine nerds because they tended to do things like read incredibly difficult books, books with intellectual cachet, prominently. They read Franz Kafka. They carried around James Joyce’s Ulysses. If they were female, they often swore allegiance to Sylvia Plath. The danger of belonging to this particular category is a kind of intellectual snobbery, but considering all the dangers of high school, intellectual snobbery is a fairly minor one, on the level of getting burnt by a toaster.

In college, I continued to write poetry. I continued to submit to the school (now university) literary journal, and at one point I was even on the literary journal’s editorial board. I continued to be published. But in college something changed. I started taking classes in writing poetry, and by the time I graduated from college, I was not sure if I wanted to write poetry anymore. I had been taking classes with famous poets (there were a several of them at the University of Virginia, where I went as an undergraduate), and they not only undermined my confidence in my own ability to write, but also made me question whether poetry was worthwhile. I think there were two reasons for this. First, the classes were intellectually lazy: they took place once a week, for several hours, and during those hours all we did was sit around and critique other students’ poetry. There was no rigor to the classes, no actual teaching. The teacher would lean back and let us do most of the work. Second, the teachers all emphasized the poetry that was then in fashion. This was the late 1980s, so confessional poetry still seemed fresh and innovative. That was the poetry we were supposed to be writing. It was all free verse of course, but not free verse in the way earlier 20th century poets had used it, with underlying rhythms and playful patterns. It felt loose, like one of the beanbag pillows that were popular then. And it felt insular, almost parochial (we never studied foreign poetry — it was always the American, sometimes English, poetry of the 1970s and 80s.) I could not make myself interested in it. If that was the direction poetry was heading in, I wanted out.

If I were to teach an undergraduate class in poetry, I would not start with workshopping at all. No, I would say, first we’re going to start by doing exercises. You’re going to write poetry in different forms: ballads, sonnets, villanelles. Because when Picasso was your age, he was imitating Velasquez. That’s how he eventually became Picasso. And it’s going to be bad, because you’re all going to be terrible at writing formal poetry — most people are. But it’s going to make you better poets, whether you’re writing in forms or in free verse. And we’re going to study the history of poetry, particularly in English but also in translation because you need to look beyond your own literary tradition. In this class you’re going to work . . . That’s the class I wish I’d had, a class that would have taught me about poetry in a deep way. That’s the sort of class I think would have inspired me.

I should rephrase my earlier statement: I still wanted to write poetry, but I no longer wanted to be a poet. Being a poet seemed incredibly pretentious, artificial — an extension of the intellectual snobbery that had seemed so cool in high school. By this point I was in law school, and I was still writing poems, on scraps of paper as I had when I was a teenager, then typing them into my computer and printing them out on a dot-matrix printer. I started sending them to small literary magazines, very small because I had no confidence in my own writing anymore. And my poems were accepted, as they had been when I was in high school and college. So I was still writing and publishing: what had changed was something inside me. I wrote though law school, then through being a lawyer — I have poems I still remember writing in my 42nd floor office in downtown Manhattan. Honestly, they were not particularly good poems. A few of them were good enough that I included them in my poetry collection, but most of them will remain hidden in my notebooks . . . The percentage of good to not-publishable was pretty low. Still, when I look at my own poems, even as far back as high school, I see something in them I like, a way of using words, an inventiveness. Writing all those poems made me the writer, including the prose writer, I am.

After several years of working as a lawyer, I went back to graduate school for a PhD in English literature. I continued to avoid poetry — all my graduate work was in prose fiction. But I wrote poetry in secret. I didn’t submit much, because it didn’t seem worthwhile. By this time I was attending fiction-writing workshops (Odyssey, and then Clarion), and I was starting to sell short stories. Unlike poetry, those paid — and editors reprinted them, so they continued to circulate, to get attention. Since my first fiction sale, I’ve been writing short stories regularly. Some of them have been finalist for or won awards, and of course I’ve been paid for them, sometimes well, but always something. My first novel will be coming out in 2017. Until a few weeks ago, I’d mostly given up on poetry. I realized, from looking at my notebooks, that I rarely wrote it anymore. At one time, I would write approximately a poem a week. Recently, there have been years when I wrote one or two . . . for the entire year, and then only because I was asked by an editor who wanted a poem for a specific purpose.

So what changed in the last few weeks? Nowadays I’m a teacher, teaching writing of all sorts, to both undergraduates and graduate students. Since November, I’ve been so busy with end of the semester work that I haven’t had time to write, and that’s not good. When I don’t write, I don’t feel quite myself . . . So I’ve been writing poetry, because that’s something I can do over breakfast, or in between teaching classes. I can finish a poem in a day and feel a sense of accomplishment. But I had to think about what to do with those poems. I didn’t want them to languish in notebooks. Trying to publish them in literary magazines no longer seemed worthwhile. When I sent poems to magazines, they were usually accepted. But it could take weeks to months before I heard back, and longer than that for the poem to actually be published. And I certainly didn’t write poetry for the money — the average payment for a poem is between a copy of the magazine and $20. Once the poems were published, few people read them — few people read literary magazines anyway, and poems get the least attention of all.

And yet . . . the few times I had shared poems online, people had liked them. They had reshared them, commented on them. That surprised me . . . I thought, why don’t I just continue to do that? So I started sharing poems on my blog. That had a magical and unexpected effect: I started writing more poetry. I think when you’re a creative person, you need to get whatever it is you’re creating out, so you can create more. If you keep it in, it starts getting blocked up, and then what you’re left with is stagnant water, like the pool behind a beaver’s dam. You want the creativity to flow like a stream. Once I started putting the poems out there, publishing them online, I started writing a lot more. And that felt good . . .

But I started running out of room on my blog. So I created a new blog, dedicated specifically to poetry. It’s called, quite simply, Theodora Goss: Poems. You can go take a look . . .

The poetry I write is rooted in myth and legend and fairy tale, not as a conscious choice but because those are the things that inhabit my head. They assume the world is deeply alive because that is how I approach the world. In a way, they are the clearest statements of what I believe in and care about — even more than my prose. They are deeply influence by the poets I have loved, some of them poets who are fashionable (W.B. Yeats, Anne Sexton), some of them poets who fell out of fashion long ago, or never were fashionable in the first place (Mary Coleridge, Robert Graves). I am particularly influenced by the history of women writing fantastical poetry, such as Christina Rossetti and Sylvia Townsend Warner. In their poetry I find a subtle subversiveness, and a fine feeling for the underlying magic of human existence. And that, fundamentally, is what I write about.

The blog is an experiment — we’ll see if it works. But my goal is simply to write more poetry and share it. If it does that, it will have fulfilled its purpose.

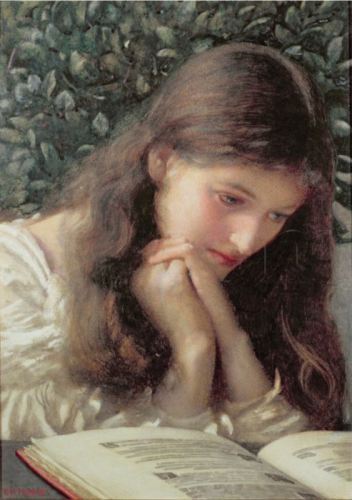

(The painting is by Edward Robert Hughes.)

December 12, 2015

The Bear’s Daughter

The Bear’s Daughter

by Theodora Goss

She dreams of the south. Wandering through the silent castle,

where snow has covered the parapets and the windows

are covered with frost, like panes of isinglass,

she dreams of pomegranates and olive trees.

But to be the bear’s daughter is to be a daughter, as well,

of the north. To have forgotten a time before

the tips of her fingers were blue, before her veins

were blue like rivers flowing through fields of ice.

To have forgotten a time before her boots

were elk-leather lined with ermine.

Somewhere in the silent castle, her mother is sleeping

in the bear’s embrace, and breathing pomegranates

into his fur. She is a daughter of the south,

with hair like honey and skin like orange-flowers.

She is a nightingale’s song in the olive groves.

And her daughter, wandering through the empty garden,

where the branches of yew trees rubbing against each other

sound like broken violins,

dreams of the south while a cold wind sways the privet,

takes off her gloves, which are lined with ermine, and places

her hands on the rim of the fountain, in which the sun

has scattered its colors, like roses trapped in ice.

(This poem was originally published in The Journal of Mythic Arts. It was reprinted in my poetry collection Songs for Ophelia The illustration is by the Russian artist Boris Olshansky.)

December 11, 2015

How to Make It Snow

How to Make It Snow

by Theodora Goss

First you must fall down the well.

At the bottom of the well

is the country at the bottom of the well.

That is its name, the only one it has.

You have two names, either the beautiful girl

or the kind girl, depending

on what day it is.

At the bottom of the well is a green meadow,

just like in the country you came from

but different. For one thing, the cows can speak.

They say, “Scratch our backs, scratch us

under the chin,” and you do.

The meadow is filled with poppies

and cornflowers. The air is warm,

and the sun is shining.

“Thank you, beautiful girl,” say the cows

and you walk on.

Across the meadow, there is a narrow path

worn by cow hooves. Follow it.

First you come to the oven.

“Take me out, take me out,” cries the bread.

“I’m burning up!” You take it out,

a brown wholemeal loaf. Carry it with you

for the birds — they appear later.

Next you come to the apple tree.

“Shake us down, shake us down,” cry the apples.

“We’re ripe!” So you shake the branches, as though

you were dancing with them.

The apples come tumbling down.

You put three in your pocket.

Now you are at the edge of the forest

and the birds call, “Feed us, feed us!”

You ask the loaf, “May I?”

“This is what I was baked for,” says the loaf.

So you scatter breadcrumbs

and the birds come, sparrows and chickadees,

robins and finches and juncos,

and a nuthatch. They perch on your arms

as you feed them. Absentmindedly,

you whistle as they do.

In the forest, a wild sow approaches.

For the first time you are afraid and step back,

but she says, “My little ones are hungry,

and I smell something sweet.”

You pull the apples out of your pocket.

“May I?” you ask, and the apples reply,

“This is why we fell.”

You kneel while the sow watches protectively,

feeding the apples to her three piglets,

bristle-backed, with tusks just starting to form

but still striped as though someone had marked them

with her fingers. The sow nods and says,

“You are a kind girl.” Then, followed by her progeny,

she disappears into the trees.

You continue alone.

It is getting dark. You have passed through the oaks

and now it is all pines. You are walking on needles.

The light is fading when you come to the cottage.

It looks like the cottage out of a fairy tale:

peaked roof like a witch’s hat, dark green trim,

small-paned windows through which firelight is flickering.

Someone is waiting for you.

You have nothing left, no bread, no apples.

So you knock.

The woman who answers is old, small,

like a doll made of cornhusks.

“You’re hungry,” she says,

“and tired. Come in, my dear.

The soup is almost ready.”

There is a fire, and a cauldron on the fire,

and a chair by the fire, and a cat in the chair,

and you can smell the soup.

“Come on, then,” says the cat, and gets up,

but only to settle again in your lap

once you sit down.

Here are the things you know about the old woman:

she milks the cows, she causes the apples to ripen,

she teaches the birds their songs, she runs her fingers

along the backs of the wild piglets

to put the stripes on them.

Here are the things she knows about you:

everything, also your name.

“What are you called, my dear?” she asks.

“The beautiful girl,” you answer. “Or the kind girl.”

“No,” she says. “From now on, you shall be

she who makes it snow.

Or Holle, for short.”

Holle: it suits you.

“Here’s what I’d like you to do tomorrow morning.

Sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains and wind the clock,

polish the silver. And when that’s done,

shake out my bedspread until the feathers

fly like snowflakes. It’s time for winter.

Can you do that?”

You nod. Yes, of course.

That night you sleep under the cat,

in her attic bedroom.

The next morning, you put on an apron she left for you,

then sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains in a metal basin,

wind the clock and polish the silver. Finally,

you stand on the cottage steps under tall pines

and shake out the old woman’s bedspread.

Snow falls and falls, until

the forest is silent.

“Well done, my dear.” She’s wearing a gray wool coat

and carrying a battered suitcase. “Can you do that again

tomorrow morning, and the day after tomorrow?

I need to visit my sisters, and I’m not sure

when I’ll be back yet.

It takes a responsible girl, but I’ve heard good things

about you from the cows, the bread, the apples,

the birds, even the trees. And the cat likes you.”

“I’ll do my best,” you say.

She kisses you on both cheeks, then rises up, up,

through the trees until she is only a speck

in the colorless sky.

You go back into the cottage.

There is a cat to scratch under the chin,

and books with stories you have never read,

and you haven’t introduced yourself to the clock yet.

Besides, you like your new name.

It’s the right name for a woman

who makes the snow fall.

(If you know fairy tales, you’ll recognize this poem as a sort of prequel to the Grimms’ “Frau Holle.” I could not find a source for the illustration, but I’m guessing it’s from an early 20th century edition of Nursery and Household Tales.)

Lady Winter

Lady Winter

by Theodora Goss

My soul said, let us visit Lady Winter.

Why? I responded. Look, the leaves still lie

yellow and red and orange in the gutters.

The geese float on the river. On the sidewalks,

puddles continue to reflect the sky.

My soul said, the branches are bare.

And you can feel it, can’t you, in your bones?

The chill that is a promise of her coming.

The year is growing older. Anyway,

you haven’t seen her in so long: it’s time.

We put on our visiting hats.

I stood admiring myself in the mirror

while my soul stood beside me looking pensive

and pale. Was she a little sick? I wondered.

Lady Winter lives on an ancient street

lined with elms that canker has not touched,

in a tall brownstone with lace curtain panels,

empty window boxes, two stone lions.

We rang the bell and heard it echoing.

A maid opened the door. Her name is Frost.

My lady looked the way she always does:

white hair, a string of pearls, rings on her fingers,

age somewhere between forty and four thousand,

a kind, implacable smile.

She said, my dear, what’s wrong? You don’t look well.

What, me? I’m fine. Perfectly fine, I said.

My soul just shook her head.

My lady has a parlor with a fireplace

in which I’ve never seen a fire. Instead,

it’s filled with decorative branches. Doilies

lie like snowflakes on the tables, bookshelves,

over the backs of armchairs.

She’s always wearing a gray cashmere sweater

and expensive shoes. She must have a closetful.

She usually serves us tea and ladyfingers.

But this time she said, I want you to go to bed.

Frost will take you upstairs, then I’ll come up

to cover you in blankets of felted wool,

comforters stuffed with down from eiderducks

that nest by Norwegian fjords. I’ll read you books

of fairytales about bears and princesses,

and stolen crowns, and castles beneath the sea,

and northern lights.

Grandmothers who grant wishes, talking reindeer,

a village in the clouds.

I’ll talk to you until you fall asleep.

Your soul will sit and watch through the long night.

From time to time she’ll take your temperature

to make sure you’re all right.

So I lay down in Lady Winter’s guest room:

reluctantly, but it looked so inviting,

a bed with draperies and a painted ceiling

from which the moon was hanging

by a silver chain.

My soul sat down beside me.

Don’t worry, she said. There’s plenty for me to do.

Poetry to embroider, plans to knit.

I’ll wake you when the crocuses have broken

through the black soil, when warmth has come again.

Then Lady Winter put her soft, dry hand

like paper on my forehead

and she said

rest now.

(The image is by Elizabeth Sonrel.)

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.

The Gold-Spinner

The Gold-Spinner

by Theodora Goss

There was a little man, I told him.

I gave the little man my rosary,

I gave the little man my ring,

my mother’s ring, which she had given me

as she lay dying. A thin circlet of gold

with a garnet, fit for a commoner.

As I was a commoner, I reminded him.

Nothing magical about me.

Very well, he said. You may go

back to your father’s mill. I have no use

for a miller’s daughter without magic in her fingers.

I’ll keep the three roomfuls of gold.

I walked away from the palace, still barefoot,

still dressed in rags, looking behind me

surreptitiously, afraid he would change his mind.

Afraid he would realize he’d been tricked.

I mean, what kind of name

is Rumpelstiltskin?

But he would have kept me spinning

in a succession of rooms, forever.

I passed my father’s mill without entering,

either to greet or berate. I wanted you to be queen,

he had told me, after I said how could you

betray me like this?

You deserve that, you deserve better

than your mother. What kind of life

did I give her?

No, I wasn’t going back there.

By mid-afternoon I had left the town,

I had forded the river, I had come

to unfamiliar fields. I sat me down

by a hedge on which a few late roses bloomed

and from a thorn I plucked a tuft of wool

left by a passing sheep. I spun,

twisting it between my fingers

as my mother had taught me.

She, too, had the gift.

I coiled the resulting thread

of thin, soft gold

around my wrist. Somewhere along the road

it would buy me bread.

Until then, there were crabapples

and blackberries to share with the birds.

And the road ahead of me,

leading I knew not where, but somewhere different

than the road behind.

(The illustration is by Anne Andersen. Except in my poem, of course, there is no little man . . .)

The Stepsister’s Tale

The Stepsister’s Tale

by Theodora Goss

It isn’t easy, cutting into your feet.

Years later, when I had become a podiatrist,

I learned the parts of the feet. Did you know your feet

contain a quarter of your bones? Calcaneus, talus, cuboid, navicular.

Lateral, intermediate, and medial cuneiform.

Metatarsals and then the phalanges, proximal, middle, distal.

They’re beautiful on the tongue, these words from a foreign language.

My sister cut into her heels, which are in the hindfoot.

I cut into my big toes, called the halluces.

She cut into flesh and tendon and sinew.

I cut into bone, between the phalanges,

through the interphalangeal joint.

That’s in the forefoot, which bears half the body’s weight.

To this day, both of us walk with a slight limp.

The problem is you do desperate things for love.

We loved her, the woman who wanted us to be perfect:

unblemished skin, waist like a corsetier’s dream,

feet that would fit even the tiniest slipper.

And so we played the aristocratic game

of identify-the-princess.

Sometimes it’s a slipper, sometimes a ring.

Oh mother, love me without asking me to scrape

my fingers like carrots, cut off my heels and toes.

Eventually, she became your favorite daughter,

the cinder-girl, the princess-designate.

She was the best at being perfect, but abuse

will do that to you.

A woman comes into my office, asking me

to cut off her little toes so she can wear

the latest fashion. I sit her down and say

did you know your feet provide the body

with balance, mobility, support?

Come, let me show you a model: here’s the toe,

metatarsal and phalanges. You can see

how elegantly they move, as in a waltz,

surrounded by your blood vessels and nerves,

the ball gown of your soft tissue,

a protective coat of skin, the delicate nail.

Look, underneath, how beautiful you are . . .

(This illustration is by Charles Folkard, for an edition of Grimms’ fairy tales.)

The Witch-Girls

The Witch-Girls

by Theodora Goss

The witch-girls go to school just down the street.

I see them pass each morning with their brooms

and uniforms: black dresses, peaked black hats.

They giggle just like ordinary girls,

except that as they walk, their brindled cats

twine around their ankles. One will stop

and say, “You’ll trip me, Malkin,” scoldingly.

Then Malkin will look up and answer back,

“Carry me then.” The witch-girl will bend down,

scooping the cat into her arms, and perch

him on her shoulder. So the witch-girls pass.

I wish I could be one of them. Alas,

I don’t know how to fly on windy nights

or talk to bats, or brew a magic potion.

Although I think I could be good at witching.

I’d learn to curse and never comb my hair.

I’m pretty good at scaring passers-by

by making goblin faces through the window.

I’d trade white cotton dresses for black wool,

no matter how it itched. I’d fly my broom

up to the witches’ garden on the moon

where they dance nightly, kicking up their heels

with sylphs and fauns and ghouls. At least I think

that’s what they do. I don’t think witches go

to bed at nine, or even make their beds

each morning. No. Instead, they marry toads,

or live alone and read old books. They paint

landscapes in Germany, or climb the Alps,

or sit in Paris cafés eating chocolate

for lunch and maybe dinner. They get drunk

on elderberry cordial, speak with bears

on earnest topics like philology.

I wonder what the witch-girls learn in school?

Geometry that helps them walk through walls,

and how to turn a poem into a spell . . .

I wish that I could go to school with them.

I’d giggle and be wicked too, if they

would only let me.

(This image is “The Little Witch” by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

December 10, 2015

Why You Might Be a Witch

Why You Might Be a Witch

by Theodora Goss

Because sometimes you dream of flying

the way you used to.

Because the traffic light always changes for you.

Because when you throw the crusts of your sandwich

to sparrows in the public park, they hop close

and closer, until they perch on your finger

and look at you sideways.

Because as you walk down the street,

the wind plays with the hem of your skirt

so it swings dramatically around your ankles.

Because as you walk, determined and sensible,

your shadow is dancing.

Because a lot of people talk to cats

but for you they answer.

Because the sweetgum trees along the sidewalk

love to show you their leaves, sometimes even tossing

them in front of you, yellow veined red,

brown shot with green and yellow,

like children showing off artwork.

Because when you look up,

the moon is always smiling.

Because sometimes darkness closes around you

and you remind yourself that it’s all right,

you’ve worn this cloak before.

Because in winter you acknowledge

that snow is a blanket as well as a shroud,

and we must all sleep sometimes.

Because in spring you can hear the tinkling bell-sounds

that crocuses make, and the deeper gongs of the tulips.

Because the river waves to you in passing,

and you wave back.

Because even the brownstones of this ancient city

look at you with concern: they want to make sure you’re well.

You belong to them as much as they to you.

Because witches know what they are

and if I asked, do you remember?

You would have to confess that yes,

you do.

(The illustration is by Ida Rentoul Outhwaite.)

How to Make It Snow

How to Make It Snow

by Theodora Goss

First you must fall down the well.

At the bottom of the well

is the country at the bottom of the well.

That is its name, the only one it has.

You have two names, either the beautiful girl

or the kind girl, depending

on what day it is.

At the bottom of the well is a green meadow,

just like in the country you came from

but different. For one thing, the cows can speak.

They say, “Scratch our backs, scratch us

under the chin,” and you do.

The meadow is filled with poppies

and cornflowers. The air is warm,

and the sun is shining.

“Thank you, beautiful girl,” say the cows

and you walk on.

Across the meadow, there is a narrow path

worn by cow hooves. Follow it.

First you come to the oven.

“Take me out, take me out,” cries the bread.

“I’m burning up!” You take it out,

a brown wholemeal loaf. Carry it with you

for the birds — they appear later.

Next you come to the apple tree.

“Shake us down, shake us down,” cry the apples.

“We’re ripe!” So you shake the branches, as though

you were dancing with them.

The apples come tumbling down.

You put three in your pocket.

Now you are at the edge of the forest

and the birds call, “Feed us, feed us!”

You ask the loaf, “May I?”

“This is what I was baked for,” says the loaf.

So you scatter breadcrumbs

and the birds come, sparrows and chickadees,

robins and finches and juncos,

and a nuthatch. They perch on your arms

as you feed them. Absentmindedly,

you whistle as they do.

In the forest, a wild sow approaches.

For the first time you are afraid and step back,

but she says, “My little ones are hungry,

and I smell something sweet.”

You pull the apples out of your pocket.

“May I?” you ask, and the apples reply,

“This is why we fell.”

You kneel while the sow watches protectively,

feeding the apples to her three piglets,

bristle-backed, with tusks just starting to form

but still striped as though someone had marked them

with her fingers. The sow nods and says,

“You are a kind girl.” Then, followed by her progeny,

she disappears into the trees.

You continue alone.

It is getting dark. You have passed through the oaks

and now it is all pines. You are walking on needles.

The light is fading when you come to the cottage.

It looks like the cottage out of a fairy tale:

peaked roof like a witch’s hat, dark green trim,

small-paned windows through which firelight is flickering.

Someone is waiting for you.

You have nothing left, no bread, no apples.

So you knock.

The woman who answers is old, small,

like a doll made of cornhusks.

“You’re hungry,” she says,

“and tired. Come in, my dear.

The soup is almost ready.”

There is a fire, and a cauldron on the fire,

and a chair by the fire, and a cat in the chair,

and you can smell the soup.

“Come on, then,” says the cat, and gets up,

but only to settle again in your lap

once you sit down.

Here are the things you know about the old woman:

she milks the cows, she causes the apples to ripen,

she teaches the birds their songs, she runs her fingers

along the backs of the wild piglets

to put the stripes on them.

Here are the things she knows about you:

everything, also your name.

“What are you called, my dear?” she asks.

“The beautiful girl,” you answer. “Or the kind girl.”

“No,” she says. “From now on, you shall be

she who makes it snow.

Or Holle, for short.”

Holle: it suits you.

“Here’s what I’d like you to do tomorrow morning.

Sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains and wind the clock,

polish the silver. And when that’s done,

shake out my bedspread until the feathers

fly like snowflakes. It’s time for winter.

Can you do that?”

You nod. Yes, of course.

That night you sleep under the cat,

in her attic bedroom.

The next morning, you put on an apron she left for you,

then sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains in a metal basin,

wind the clock and polish the silver. Finally,

you stand on the cottage steps under tall pines

and shake out the old woman’s bedspread.

Snow falls and falls, until

the forest is silent.

“Well done, my dear.” She’s wearing a gray wool coat

and carrying a battered suitcase. “Can you do that again

tomorrow morning, and the day after tomorrow?

I need to visit my sisters, and I’m not sure

when I’ll be back yet.

It takes a responsible girl, but I’ve heard good things

about you from the cows, the bread, the apples,

the birds, even the trees. And the cat likes you.”

“I’ll do my best,” you say.

She kisses you on both cheeks, then rises up, up,

through the trees until she is only a speck

in the colorless sky.

You go back into the cottage.

There is a cat to scratch under the chin,

and books with stories you have never read,

and you haven’t introduced yourself to the clock yet.

Besides, you like your new name.

It’s the right name for a woman

who makes the snow fall.

If you know fairy tales, you’ll recognize this poem as a sort of prequel to the Grimms’ “Frau Holle.” I could not find a source for the illustration, but I’m guessing it’s from an early 20th century edition of Nursery and Household Tales.)