Theodora Goss's Blog, page 15

August 23, 2015

Strange Faces

Some of us have strange faces.

Mine, when I look in the mirror, seems all bones: the jaws are prominent, the cheekbones angular, the nose prominent and angular. I have the ordinary features one has on a face, of course: eyes, for example, dark and slanting upward at the corners. But what you notice about my face, I think, is the bones. Helen of Sparta’s face launched a thousand ships and burned the topless towers of Ilium. My face looks ready to sack Rome. (My grandmother always insisted that we were descended from Attila the Hun.)

When I was young, a girl growing up in the South, I did not want to look at my face in the mirror, because it did not match my idea of what a face should look like: soft, with small features, the face of Botticelli’s Venus. That was my idea of beauty. It was also, of course, Hollywood’s idea of beauty. You’ve seen them, the young actresses with distinction and individuality, the Clare Danes, the Scarlett Johanssons. You’ve seen them in their first independent films, perhaps found them interesting, actresses to watch. Then seen them in their first Hollywood movies, their first red carpet appearances. Their features change, become softer, prettier, safer. More like the ideal vision that Hollywood shares with the Renaissance.

It was not until I was older that I discovered a different kind of beauty. I was reading Edgar Allan Poe, and there it was, the statement that revealed a new way of thinking for me: “‘There is no exquisite beauty,’ says Bacon, Lord Verulam, speaking truly of all the forms and genera of beauty, without some strangeness in the proportion.'” Wait, I said to myself. Strangeness in the proportion? What does Poe mean by that? He does not tell us, exactly, but he does give us an example: the Lady Ligeia. His unnamed narrator, who is in love with her (so in love with her! how romantic I thought that was, at sixteen), tells us that he does not know why her beauty is so enticing and yet so strange. He tells us that he “tried in vain to detect the irregularity.” Irregularity! That too was a new idea. It was the first time I had thought of beauty as being irregular. Scientists who study our perception of beauty tell us that test subjects prefer faces with symmetry: the regular is the beautiful. (Yes, the study of beauty has become a science, specifically a medical science. Why else do we buy cosmetics at the drug store? As though ugliness were a disease to be treated, by surgery if necessary. A prominent plastic surgeon has even invented a “mask of beauty,” a geometrical template that you can superimpose on your face to see how symmetrical, how beautiful, you are. Strangely, the mask itself is grotesque, the face of a robot.)

What are these irregular features, according to the narrator? A high, prominent forehead. A Jewish nose. A Greek chin. (Have you seen the chins on classical Greek statues? Those goddesses had serious chins — and jaws.) Dark eyes and hair. All of these features give Ligeia “the beauty of the fabulous Houri of the Turk.” Hey, I thought, that sounds just a little like me. (My father always insisted that his ancestors were Turkish.) Don’t misunderstand me — I was making no claim to exquisite beauty. I felt as ugly as any Hans Christian Andersen duckling. But the idea that there could be something attractive about irregularity — that stuck.

And Ligeia was smart, much smarter that the narrator himself. She spoke Greek, she wrote poetry, she was good at physics. She was even good at math, which was my personal Waterloo. Here was a beauty to identify with.

You can already see the problem, can’t you? Ligeia isn’t exactly an ordinary woman. She dies, probably of the consumption that claimed Poe’s wife, then comes back to life by taking the body of the narrator’s second wife, the blonde, blue-eyed Lady Rowena. Poor Lady Rowena, as conventionally beautiful as Venus on the Half-Shell. In the Hollywood movie, she would be played by Clare Danes. She becomes sick as well, although this time the disease seems to be the spirit of Ligeia, hovering around the macabre bedroom the narrator has created, waiting for her chance. The narrator watches as Rowena seems to die, to recover, to die again, over and over through a dreadful night. Finally, she rises from her death bed, drops the shroud she has already been wrapped in, and — but of course, it’s the Lady Ligeia, risen from the dead. Her dark eyes blazing, her dark hair falling around her. At that point, the narrator is screaming.

Years later, when I started teaching college students, I found a way to conceptualize the effect that Ligeia has on the narrator (who, remember, loves her, to the point that he longs for her return even from beyond the grave — still, he cannot help his screams). By then, I had made a sort of peace with my face. As I had grown older, it had only grown bonier, but I had grown to appreciate its irregularities. When I wrote my own stories, I often described my most interesting female characters, the ones I wanted readers to pay attention to, as birds of prey, with faces like a falcon’s and noses like a falcon’s beak. I had even learned to appreciate my nose. That was when I came upon Freud’s idea of the uncanny. Freud wrote a whole essay called “The Uncanny,” a long, rambling essay that tends to annoy my students because Freud seems to be developing his ideas as he writes, and often contradicts himself. But his central idea is simple. There are certain things that make us feel the sensation of the uncanny. They make us shudder, make the hairs on the backs of our necks stand up. Freud lists a number of these things: severed limbs that move by themselves (like Thing from the Addams family), mechanical dolls that seem to come to life (Freud mentions E.T.A. Hoffman’s Olympia, but I tell my students to think of Chucky), and numbers that keep repeating in a way that seems more than coincidental (like the number 42 in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, although there the effect is funny rather than frightening). But the heart of the uncanny is this: an intrusion of the supernatural into the world we had thought to be natural, operating according to the laws of physics. Ligeia coming back from the dead is such an intrusion. (You have to be good at physics to break its laws.) The narrator’s screams, at the end of the story, are an extreme case of the uncanny sensation Freud describes. Ligeia is uncanny and her beauty is uncanny, like the beauty of the fabulous Houri of the Turks, who are after all supernatural beings. So while her beauty will attract you, it will also make you shudder. The narrator finds her both appealing and appalling.

And she’s not the only one. There is an entire literary tradition of such appealing, appalling women. Some one should edit an anthology. (Perhaps I will, someday.) Think of Geraldine, Beatrice Rappaccini, Helen Vaughan, Carmilla, Lucy Westenra after she turns into a vampire. If you read their stories (I really should edit that anthology), you’ll find the same features, over and over. Dark eyes and hair, for one. A grudge against blondes. (Seriously, the stories are strewn with blonde corpses: Rowena, Laura, Rachel, Christabel.) Men who are simultaneously enthralled and horrified. And beauty: strange, irregular, unusual, appalling beauty.

Monstrous beauty. I use the word monstrous deliberately here, because all of these women are monsters. They return from the dead, suck people’s blood, channel ancient gods, breathe poison. Their beauty is part of their monstrousness. It allows them to get close to their victims so they can attack. Indeed, their victims wait for, anticipate the attack, holding their breaths. How delicious, to feel Lucy’s teeth at your throat. I tell my students that there is a difference between male and female monsters. Male monsters tend to be hideous: Frankenstein’s monster, Mr. Hyde, Dracula (who is not as suave as his movie incarnations). There are ugly female monsters (Grendel’s mother, the alien matching wits with Sigourney Weaver), but they are less common than the beautiful ones. Even Frankenstein’s female monster, never made in the novel because of her potential ugliness, comes to life as a shock-haired beauty in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein.

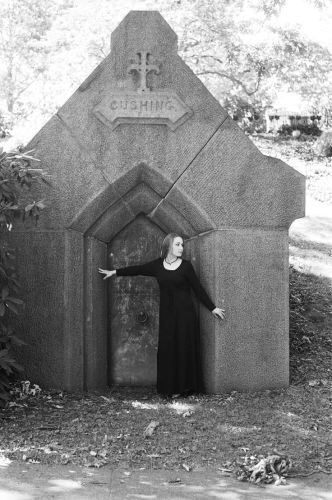

In Ligeia, I had found my role model: the uncanny beauty. In doing so, I had put myself in the company of all the female monsters of English literature and art: the sirens singing men to their deaths, sphinxes biting their heads off for not answering riddles, witches dancing on the heath, vampires claiming the night as their hunting ground. When I began to write, I began to be photographed, at conventions or workshops, for interviews or book covers. Sometimes I thought the photographs were flattering, sometimes not. I began to see photographs of myself on the internet, which gave me a sensation of the uncanny. Suddenly, the face I had seen in the mirror so many times and had spent so long coming to terms with was being presented in ways over which I had no control. So I decided to photograph myself in my own way. In a cemetery, rising from the dead. It was a small tribute to my girlfriend Ligeia, who had gotten me through being sixteen.

In women’s magazines, there is always a helpful section that tells you how to recreate a featured look. So I’m going to tell you how to become a female monster. Just in case you want to, you know, join me and my girlfriends.

1. Be deadly. If you can’t be deadly, since it is after all difficult and usually illegal to be deadly nowadays, think deadly thoughts. (For instance, about cheerleaders, yappy dogs, frozen yogurt stands, and anyone with loud headphones.) This produces the alluringly dangerous expression that men seem to die for (sometimes literally).

2. Be your own fashion trend. Wear distinctive clothes. These need not be cerements of the grave. Any style that is genuinely individual will do. Notice that the blonde victims all look alike. The monsters are all monsters in their own way.

3. Pay attention in calculus. Female monsters are wicked smart. Learn ancient Greek or any other obscure language (Croatian, Tagalog, Urdu). Read a lot of books. You can never tell when you might need to know something, like how to return from the dead or pose riddles on the road to Thebes.

4. Believe in your exquisiteness. You may have poisonous breath or turn into a serpent at night, but you deserve to be loved. Beyond death. And to have poetry written to you.

Sometimes I look at the women’s magazines in the drugstore and think, they really should have a magazine for us, the female monsters. It would not have Scarlett Johansson on the cover. No, I’m thinking Jane Morris, Sarah Bernhardt, Tilda Swinton. It would have articles on growing poisonous plants, piercing the veils of space and time, and little black dresses for under $100. Potential models would be evaluated for their uncanny beauty, on whether there was any strangeness in the proportion. It would be a plus if they had serious (not adorable, not retoussé) noses. I would buy it. Wouldn’t you?

(This essay was originally published in the special “Uncanny Beauty” issue of Weird Tales, 2010. I decided to repost it here, for all you uncanny beauties. The photos are, yes, from the photoshoot I described. They must be fifteen years old! My face has only gotten bonier . . . )

August 17, 2015

Shoes of Bark

Shoes of Bark

by Theodora Goss

What would you think

if I told you that I was beautiful?

That I walked through the orchards in a white cotton dress,

wearing shoes of bark.

In early morning, when mist lingered over the grass,

and the apples, red and gold, were furred with dew,

I picked one, biting into its crisp, moist flesh,

then spread my arms and looked up at the clouds,

floating high above, and the clouds looked back at me.

By the edge of a pasture I opened milkweed pods,

watching the white fluff float away on the wind.

I held up my dress and danced among the chickory

under the horses’ mild, incurious gaze

and followed the stream along its meandering ways.

What would you think

if I told you that I was magical?

That I had russet hair down to the backs of my knees

and the birds stole it for their nests

because it was stronger than horsehair and softer than down.

That when the storm winds roiled,

I could still them with a word.

That when I called, the gray geese would call back

come with us, sister, and I considered rising

on my own wings and following them south.

But if not me, who would make the winter come?

Who would breathe on the windows, creating landscapes of frost,

and hang icicles from the gutters?

What would you think, daughter, if I told you

that in a dress of white wool and deerhide boots

I danced the winter in? And that in spring,

dressed in white cotton lawn, wearing birchbark shoes,

I wandered among the deer and marked their fawns

with my fingertips? That I slept among the ferns?

Would you say, she is old, her mind is wandering?

Or would you say, I am beautiful, I am magical,

and go yourself to dance the seasons in?

(Look in my closet. You will find my shoes of bark.)

The painting is La Primavera by Henry Ryland. This is another of the poems I read at Mythcon. It can be found in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

(Do I really have shoes of bark in my closet? You know I do . . .)

August 10, 2015

Teaching at Stonecoast III

I meant to write my third blog post on teaching at Stonecoast before I left for Mythcon, but I just didn’t have time. It’s been such a busy summer . . . But here it is, the third and final post. I think last time I was talking about the workshop on writing short stories that I co-led with James Patrick Kelly? He led two days, and I led two. On the first of my days, I talked about the things I look for in a short story and try to put into a short story myself. On my second day, I talked about ways in which I break the rules — or expectations would be a better word, because the truth is there are no rules. Just ways we think stories ought to go, expectations we have of narrative. If those expectations aren’t met, we tend to be grumpy — unless the writer is good enough to “break the rules” effectively.

Bowdoin, by the way, has the most beautiful small jewelbox of an art museum. On one of our last days in Brunswick, I and a couple of other faculty members found time to visit and see an exhibit on painting the night, which was fascinating and very well curated. You can see the front of the museum here:

But actually you enter through a class addition to the side of the main building. You go down the steps or elevator, into the basement shop and gallery. And from there you can go back up again, into the main building. You’re not allowed to take pictures in there, or I would have some to show! Here was the sign for the exhibit:

Back to breaking the rules, such as they are. I told the students that I like to make things difficult. For example, in “The Rose in Twelve Petals” I changed the entire history of England. I’m not sure how much my reader will notice that, but I think it adds a layer of density and interest to the story. In “Child-Empress of Mars,” I included words in “Martian” that I never explained. Because . . . I could! I got away with it. So how do you get away with it? Well, first it has to be intrinsic to the story, not something you add simply for the sake of being difficult. Second, the story has to make sense, to still satisfy, without it. The reader has to be able to understand my story despite the alternate history in the background, or despite the “Martian.”

Why break the rules in the first place? (And by “break the rules” I mean “not meet reader expectations” — the reader expectations are all the things I talked about in my second blog post, on what I try to do in a short story.) After all, it makes the story more difficult both to write and read.

Well first, the story might need to be told in a different, unconventional way. You might not be able to tell that particularly story conventionally. Second, you might want to play with form and narrative structure. That’s a perfectly legitimate reason: you’re allowed to play, to experiment. So it could be driven by the story, or by you. Third, there is a pleasure in difficulty, both for writer and reader. You might want that pleasure . . . And you’re allowed to break the rules all you want to. But there are consequences, and you have to accept those.

This, by the way, is the program from the Stonecoast graduation ceremony. I always love going to graduation, seeing the brand-new MFAs. Including students I’ve helped complete their theses!

So how do you do it? You can play with any of the elements I discussed: setting, characters, plot, etc. You can break the rules a little or a lot. In general, the more you break the rules, the more you need to give the reader something to hold on to (in “The Rose in Twelve Petals” it’s the fairy tale plot; in “Child-Empress of Mars” it’s the parody of the John Carter books).

I gave the students an example of where I had broken the rules: my story “Beautiful Boys.” It doesn’t do any of the things I talked about a short story doing: it doesn’t start quickly, and one could make the case that it doesn’t start at all — it keeps trying to start; there is no concrete setting; the narrator is never fully described and is unreliable anyway; the only other character may or may not be an alien, we don’t know; there’s no plot, not really — except maybe the professor got pregnant by an alien, or maybe not; and the ending doesn’t resolve anything. It leaves us hanging. What the story does have, though, is a pretty clear emotional stake — at least, I think it does. And it taps into our own memories of the bad boys of our youth, the ones who got into trouble, and started bands, and dated cheerleaders. It’s anchored in our own knowledge of how difficult and painful relationships can be.

So what are the consequences of breaking the rules? Well, there are both good and bad consequences. The possible bad consequences is that readers may get mad at you, and the story may be harder to sell in the first place. I remember a reader commenting on “Beautiful Boys” that while he liked it, it wasn’t science fiction, and therefore shouldn’t have been published in Asimov’s. But if you can pull off a difficult, complicated, innovative, rule-breaking story? That’s the sort of story that gets attention, that is discussed, possibly nominated for awards. There are rewards for breaking the rules.

We had a beautiful week at Stonecoast, but toward the end it rained. That’s me in a puddle, above. I mean, reflected in a puddle — I didn’t have to live in a puddle. No, I stayed at a beautiful inn. (But what if the selves we are in puddles have their own consciousness, their own lives? The problem with being a writer is that you never really stop being a writer . . . The entire world becomes story.)

There was one more thing I talked about, at the end of the workshop. What I often see is that writing is limited by the writer. The writer can’t write better stories because he or she isn’t more open, more vulnerable to the world. The writer doesn’t listen or experience enough. Part of becoming a writer is creating yourself — like a dancer, you are the instrument of your art. So you need to become the best instrument possible. How do you do that?

You deliberately experience: read books, visit museums, listen to concerts, talk to people. Travel to countries and places other than your own. So many people in this world limit themselves, but if you want to be a writer, you shouldn’t — really, you can’t. You need to take in, to observe, to experience, a great deal — and then filter it through yourself so that it becomes a part of you, and comes out of you, as your own.

You do need to make sure that you don’t become overwhelmed, but think of this as a sort of diet for your mind. Just as you want to eat a healthy and varied diet for your body, you want a diet for your mind — not to eat everything, but to deliberately experience, observe, learn. A dancer might work on her pliés — you might read poetry. Or listen to people talking on the subway.

Ultimately, the work comes out of you — so you need to work on yourself, as well as on the writing.

Have I mentioned that Bowdoin is filled with lions?

And that’s it for my Stonecoast residency! Although I might still post about the presentation I made on Magical Realism. But I hope this has given you an idea of what the residency was like, what I did there . . . and that there were some useful ideas in it, for the writers among you.

August 6, 2015

The Gentleman

The Gentleman

by Theodora Goss

Has the milk gone sour this morning?

are there tracks upon the floor

where you could have sworn you swept

carefully the night before?

Are the window shutters open?

Did the clock forget to chime?

Could you simply have forgotten

to set the time? Surely not.

Are the chickens agitated?

could a fox have come last night

and sniffed around their coop,

to put them in a fright?

There’s a fox that walks on two legs;

when he comes, the farmyard dog

pricks his ears and sits as silent

as a log. Unfortunately.

Is the horse’s mane completely

in a tangle, and its hide

crusted with the mud that splashed

from its hooves during the ride?

That’s how you know. The Gentleman

does love his nightly ride. And the maid

milking the cows this morning smiles

mysteriously. Oh, for goodness’ sake.

You should do something. Gather

the town together, determine to catch

the malefactor. How many of you

have had your tulips trampled,

your best cow addled, your daughter

suddenly dreamy? But. What

if he were brought to justice,

black boots in the courtroom,

black eyes laughing at you,

at the good wives, industrious,

neat as a pin in their cotton

gowns, making you feel,

well, ridiculous, and somehow flushed,

and worse, what if the cabbages

bolted, and the asparagus flopped,

and the squash were all infested

with worms. You can’t trust him.

And worse yet, what if the moon

refused to change, and the leaves

on the trees never caught the fire

of autumn. And it was your fault.

I tell you, my dear:

If the milk was sour this morning,

and the laundry is in knots,

if the geraniums are missing

from their flowerpots,

if the mice have gotten into

the bacon and the cheese,

laugh and let the Gentleman do

as he pleases. I know, what a mess.

But a robin’s on the handle

of the shovel, singing softly,

and the clouds are floating overhead.

Admit, the world is mostly

as it ought to be. Tonight the moon

will pull the distant tide,

and the Gentleman will come to take

his nightly ride. With a kiss for you

even if you don’t notice.

But my dear,

you do.

This is Portrait of a Gentleman in his Study by Lorenzo Lotto. I looked through many portraits of gentlemen to find one that seemed even remotely as though he could be mine . . . most of them seemed quite stuffy! But Lorenzo’s might be the mystical gentleman who takes his nightly ride. I recently read this poem at Mythcon, and thought I would post it here. It appears in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

July 26, 2015

Teaching at Stonecoast II

This is the second in my “Teaching at Stonecoast” series, about what I did during this summer’s Stonecoast MFA Program residency. In this post, I want to talk more about the sorts of things we covered in my two workshops. The first workshop was for new students: it oriented them to Stonecoast and got them started workshopping stories. The second workshop focused specifically on short fiction, and was co-led with my own former teacher, the science fiction writer James Patrick Kelly.

This is the first building I would enter every day: where we held our graduating student presentations. I told you Bowdoin is beautiful!

In my first workshop, after we had workshopped the two stories for the day, I walked about elements of a story: setting, character, plot, and style. (We only had four days, so four elements). For each, I had three examples, and toward the end of the workshop we would read and discuss them. Here’s one:

“You never saw such a wild thing as my mother, her hat seized by the winds and blown out to sea so that her hair was a white mane, her black lisle legs exposed to the thigh, her skirts tucked around her waist, one hand on the reigns of the rearing horse while the other clasped my father’s service revolver and, behind her, the breaker of the savage, indifferent sea, like the witness of a furious justice. And my husband stood stock-still, as if she had been Medusa, the sword still raised over his head as in those clockwork tableaux of Bluebeard that you see in glass cases at fairs.

“And then it was as though a curious child pushed his centime into the slot and set all in motion. The heavy, bearded figure roared out aloud, braying with fury, and, wielding the honorable sword as if it were a matter of death or glory, charged us, all three.

“On her eighteenth birthday, my mother had disposed of a man-eating tiger that had ravaged the villages in the hills north of Hanoi. Now, without a moment’s hesitation, she raised my father’s gun, took aim and put a single, irreproachable bullet through my husband’s head.”

This is from a story called “The Bloody Chamber,” by Angela Carter. If you’re looking at it as a writer, there are all sorts of things you notice: the point of view, for example (first person, talking directly to us). The pacing, which stops and starts: the movement of the mother, the stillness of the husband, the movement of the husband, then the pause in narrative momentum as we learn about what the mother did when she was eighteen. And then, suddenly, the shot. The pacing is brilliantly handled. Word choice: “seized,” “blown,” “exposed,” “tucked,” “rearing,” “clasped” . . . all the active verbs. And then the opposition of Medusa and Bluebeard, two different mythical figures, almost as thought the story were posing a hypothetical question: in a matchup between Medusa and Bluebeard, who would win? Medusa, duh.

My goal was to get the students to think, not like readers, but like writers. That creates its own problems . . . you can’t read stories the way you used to, anymore. But putting together even the shortest story is an act of craft, and writers need to learn the craft. (There’s art too, but you don’t learn art. You become an artist. Art isn’t taught but embodied.)

So that was my first workshop, and I was very happy with how it went.

Oh, I’ve forgotten something! I also gave the students an exercise: they had to write pieces of flash fiction (no more than 1000 words) and send them to me. For the last class, I compiled them, then gave the students the stories without the authors’ names. I had written one myself, because if you make a student do something, you should always be willing to do it yourself as well. During our last workshop, we discussed the stories — then they had to vote on who had written which one. I was the only one who knew. If you’re a teacher, steal this exercise — I stole it myself from Jim Kelly. Every time I’ve done it, I’ve gotten writing from students that was actually more creative, more innovative, than the polished stories they had turned in. In the short format, students felt free to try something new. At least once, when I tried an exercise like this, it turned into a student’s first published story.

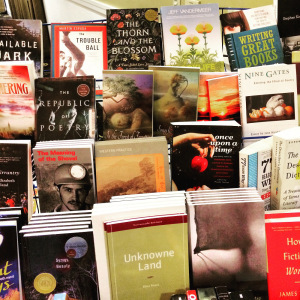

This is a small part of the book table, with my books on it. We would pass the book table every day on our way to lunch . . .

And what about the second workshop? That was filled with students who had been at Stonecoast for at least one semester, students who were already writing steadily, some of them starting to publish. That workshop was really about how to turn short stories that were already interesting and well-written into stories that would hopefully be published by one of the genre markets. Jim and I took turns leading the workshop. On our days, we both also lectured briefly on aspects of writing short stories. On my first day, I talked about the components of a short story, the things I wanted a short story to do and have, taking examples from my own stories. Here are the things I covered:

1. I want a short story to start quickly. The setting, central characters, and theme should be established by the second paragraph. But while the first two paragraphs are about establishing, about creating stability for the reader, they are also about destabilizing the reader. I want to create the forward momentum that will carry the reader through the story. What does the reader not know? Give your reader both a jumping-off place and a direction to jump, I told them.

2. I want to create a setting that is dense, appealing to multiple senses. The setting should be both immediate (where are the characters now?) and expansive (what is their larger world like?). A good description of setting should do both.

3. I want to describe characters quickly, with descriptions that give a sense of the inner and outer at once: both what the character looks like and what the character is like. And if another character is doing the describing, the description should say as much about that character as the one being described.

4. I want to continually advance the plot. Here I talked about my favorite definition of plot, from E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel. Actions, if they are to be part of the plot, should have consequences. So think through the consequences of each action . . .

5. I want to raise the stakes, and the stakes are always emotional. The plot means nothing if we don’t care. (I don’t think I mentioned Vladimir Nabokov’s injunction that the author should put her character up a tree and throw rocks at him. But I think that sort of rock-throwing is important.)

6. I like to reveal secrets, things the reader doesn’t know, and maybe the character doesn’t know either. I like to lead up to the revelation of a secret. I think this makes the story more interesting, like a mystery . . . The revelation should be both inevitable and surprising.

7. I want to conclude effectively. The conclusion should bring together both the inner and outer arcs of the story: the emotional arc and the arc of the action. It can be a big ending or a small one: an ending that underplays the emotional consequences is often more effective than a big fireworks-going-off conclusion. In the example I chose, two men are walking together, talking about breakfast, and the important thing is mentioned as an aside: one of them has chosen to stay in his homeland and fight the Germans. We know that World War II is coming, although they’re talking about sausage and eggs.

This post is already a bit longer than I intended, so I see that I’ll have to go on to a third one! In it, I’ll talk about what I discussed on my second day leading the workshop: breaking the rules and becoming an artist. The handsome beast above is one of the stone lions in front of the Bowdoin art museum, and a close personal friend.

And below you’ll see one of my favorite things in Brunswick, which is Heath Bar frozen yogurt with Heath Bar topping, from an ice cream shack named Cote’s that is about a block from the inn. This is a “mini” and sells for three dollars (the next size up is a small, which is, you guessed it, not particularly small).

July 25, 2015

Teaching at Stonecoast I

I’m recovering from the Stonecoast summer residency. What, you may ask, is Stonecoast? And what is a residency? Stonecoast is the MFA program in which I teach, and the residency is a ten-day period when all the students and faculty get together, twice a year, for workshops, seminars, and readings. It’s the most intense teaching I do, and I love it.

For those of you who are interested, I thought I would describe what it’s like teaching in one of the top low-residency programs in the country, and one of only a few that have a Popular Fiction track. That’s what I teach: Popular Fiction. My students write science fiction, fantasy, mystery . . . And of course they also write literary fiction, poetry, essays. Being on the Popular Fiction track doesn’t prevent you from writing, or taking workshops in, other modes or genres. But most of what I do in the program tends to focus on popular genres, in one way or another — or the places where genres intersect.

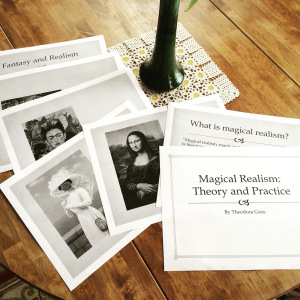

So what was I doing, exactly? Well, first I had to prepare for the residency. That meant reading and commenting on the stories from the two workshops I would be leading. The first half of the residency, I would be leading a workshop for the newly-admitted students, which would prepare them for workshopping at Stonecoast in general. It would be both workshop and orientation. I’d never done that before, so I was particularly looking forward to it. The second half, I would be co-leading a workshop focused specifically on writing short fiction with James Patrick Kelly. Now, Jim Kelly is a friend and mentor of mine — he was my own teacher at Clarion! So you can imagine how much I was looking forward to that. I would be co-teaching with my own teacher! Also, Jim is a fantastic writer of short fiction as well as a fantastic teacher in general, so I knew that I would be learning as much as I would be teaching. During the residency, I would also be giving a presentation called Magical Realism: Theory and Practice. So I created a PowerPoint, and a series of presentation notes for myself, and a reading list to hand out. Here you can see the slides from my PowerPoint presentation, which I printed out so I could proofread them:

The presentation took a lot of work, because I am not an expert on Magical Realism. As I told the students, there are things I am genuinely an expert on, because I’ve studied them intensively for years. But Magical Realism is not within my field of expertise. That’s what made doing a presentation so exciting: I had to learn about a whole new field! Of course I’d studied it a little, starting with a class on magical realist fiction in college. But I had a lot of reading to do before I could present on the topic in any coherent way. That took a couple of months! By the time I started preparing for the residency in earnest, I had enough of a background to put together my presentation — more or less confidently. So that was most of the preparatory work. I also knew I’d need to prepare a 20-minute reading, but I’d recently written a story that I wanted to read . . . so that was taken care of.

The residency took place on the campus of Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine.

If you’ve never been on the campus of Bowdoin, I will tell you that it’s ridiculously beautiful. You can just take a look at the pictures here! It looks exactly the way you would expect a New England liberal arts college to look, all green campus and stone or brick buildings. First, of course, I had to get there. I’m lucky in that I live in the Northeast, where it’s easy to get around by train. I took the Amtrak Downeaster up to Brunswick and walked from the station to the inn where faculty members were staying. For ten days, my room at the inn would be my home. I unpacked, putting clothes away, hanging blouses and dresses from the hangers — if you move in, I’ve found, you feel much more at home, even in a hotel room. And then I went shopping for supplies. Of course I could have ordered breakfast at the inn, but I found it so much easier to buy cups of oatmeal and powered chai, so that, with only the coffee maker in my room, I could make myself oatmeal and chai in the mornings. Also cereal bars and chocolate, in case I got hungry during the day — because if I get hungry, I get cranky.

So there I was, with my clothes put away, my manuscripts ready, my supplies purchased. Time to start the residency.

The residency day starts at 8:15, with graduating student presentations. This summer, I had a graduating student whom I had mentored — I had been the first reader on her thesis, and had guided her through the thesis process. Her presentation was one of the first, and I was so pleased to see how well it went, how smart it was. For her third-semester project, she had researched the history of monsters, and in her presentation she explained how conceptions of monsters had changed, from the mythical monsters, to the medieval, to the modern (particularly post-World War II). Then, after student presentations, we have workshops for two and a half hours. With my first-semester students, we generally workshopped one story, took a break, workshopped a second story, and then went on to talk about particular writing issues. I had brought a handout that included a variety of passages — for example, I’d just started reading Patrick Süskind ‘s Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, and I included the first two paragraphs, in which he describes the stench of 18th century Paris. It’s a brilliant description, a brilliant and unconventional way to start a novel. We talked about the choice of words and images, the way the author directs our attention (always conscious of the fact that we were dealing with a translation from the German).

After workshop, we had lunch, all of us together in the Bowdoin cafeteria. And then in the afternoon there were faculty presentations. After those, there was other programming, typically graduating student readings but also orientations of various sorts, such as for students going to the Ireland residency (yes, Stonecoast has an optional Ireland residency! Send me to Ireland, Stonecoast . . .). Then it was time for dinner, and then faculty readings. So the days ended at around 8:15 p.m., unless there was something even after that, like student open-mic’s. Yes, I know, twelve-hours days! That’s what a residency is like . . .

I’ve written so much already, and I haven’t really even started to describe what I did at the residency! I’ll have to write another blog post on this subject. In the meantime, here is me, sitting in one of the rocking chairs on the inn porch, going over manuscripts . . .

July 24, 2015

Autumn’s Song

Autumn’s Song

by Theodora Goss

You are not alone.

If they could, the oaks would bend down to take your hands,

bowing and saying, Lady, come dance with us.

The elder bushes would offer their berries to hang

from your ears or around your neck.

The wild clematis known as Traveler’s Joy

would give you its star-shaped blossoms for your crown.

And the maples would offer their leaves,

russet and amber and gold,

for your ball gown.

The wild geese flying south would call to you, Lady,

we will tell your sister, Summer, that you are well.

You would reply, Yes, bring her this news —

the world is old, old, yet we have friends.

The squirrels gathering nuts, the garnet hips

of the wild roses, the birches with their white bark.

You would dress yourself in mist and early frost

to tread the autumn dances — the dance of fire

and fallen leaves, the expectation of snow.

And when your sister Winter pays a visit,

You would give her tea in a ceramic cup,

bread and honey on a wooden plate.

You would nod, as women do, and tell each other,

The world is more magical than we know.

You are not alone.

Listen: the pines are whispering their love,

and the sky herself, gray and low, bends down

to kiss you on both cheeks. Daughter, she says,

I am always with you. Listen: my winds are singing

autumn’s song.

Above you will see a video based on my poem created by Belinda Farage. I thought it was so gorgeous that I wanted to share it here . . . This poem is in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

July 5, 2015

Ordinary Pleasures

Last summer, I spent a month in Budapest, taking a class in Hungarian. This summer, I organized my taxes.

I’m not kidding, I really did organize my taxes. It’s such a relief, having all that paperwork organized into individual folders, appropriately labeled. I know, it’s a lot less exotic than flying to Budapest. But this summer has been about trying to catch up on all the ordinary things that, to be honest, I’ve neglected. I’ve lived in my apartment for a year, and it’s still not entirely decorated. Granted, decorating takes a while, at least the way I do it, but still . . . I’d like to have a nice place to live in. And that takes putting in the time, doing the work. So this summer is about doing the ordinary things: working, organizing, catching up.

What I’ve found, staying in Boston this summer, is the pleasure of the ordinary. The pleasure, for example, of watching the procession of flowers. Luckily, I live in the midst of gardens: there are gardens in front of the brownstones all up and down my street, more formal gardens in city squares or close to children’s playgrounds, and even conservation areas where I can go for walks beside rivers or ponds, under tall trees. Just now the roses and clematis are almost over, although this week I still found some perfect roses in a formal rose garden not too far from me. This was one of them:

The lilies have started blooming, and the linden trees are in flower. I’m lucky to live on a street with linden trees, so I can smell the sweet odor every time I step outdoors. It seems to fall from the trees . . . Every time one type of flower fades, I feel sad because it means that summer is passing. But at the same time, it’s fascinating to see them, like the best fashion show ever. Nothing we create is as beautiful as the flowers. Mother Nature is, after all, the greatest artist. And I love walking around the city, looking at the old buildings with their beautiful details. Architecture lost both beauty and detail for a while — we were poorer for that, and are just starting to find those two things again.

What we really lost, I think, is the understanding that beauty and joy come from the small, the ordinary. Take those enormous contraptions of steel and glass created by the most famous contemporary architects. They are rarely beautiful, and they rarely give us joy. If we got rid of every single one of them, it would not impact our lives in a significant way. Compare them to a honeybee, so small and intricate. Isn’t the bee more beautiful? And if we got rid of every single one of them . . . well then, we’d be in trouble.

I don’t know what happened to our sense of the small and ordinary, but I think we need to get it back. Recently, I started watching a television show from the 1960s, and I was startled by how small things were: hotel rooms, women’s clothes, international crime syndicates. (All right, if you must know, it’s Mission Impossible. I love watching a show that is almost pure plot . . .) There are ways in which we live in a better world. No Cold War, for one. But I think as we progress, we always lose something. In this case, at least, I think we can get it back.

After I went to the rose garden, I walked to the conservancy I mentioned, which is a wetland. There is a path through the woods . . . (I thought this would be a good place for a metaphor.)

We can make a conscious decision to reclaim the small, the ordinary. We can care more about honeybees than skyscrapers. Knitting than international finance. (Don’t get me wrong: you should try to understand international finance. We need to understand what is being done to our world, if only because voting intelligently is one of those small things that make a large impact, like honeybees.) We can learn to cook or play an instrument. We can organize our taxes. Clean our bathrooms. (That’s on the agenda for today.) There is so much meaning in those small acts, and the truth is, when we do something large, the meaning of it usually comes from the small components anyway. If we write a novel, the meaning comes from all those hours we spent at our computer, trying to find the right word. From each edit. From the lessons we learned about ourselves while writing.

Aren’t the ferns gorgeous? I had to take a picture of them as I walked through the forest. It was like walking through a green world, made up of all the small things: beech leaves rustling overhead, white trunks of birches, ferns by the path, rabbits hopping under the bushes, looking at me as though wondering what I was doing in their living room, and the magnificent blue heron that was standing in the pond, with a blue heron reflected in the pond water beneath him. I thought, I’d like to have something like this, a connection of this sort, every day of my life.

Then I went home and did the small things there: made dinner, finished some sewing I’d been putting off for a while, intimidated as always by my sewing machine because tension is so complicated . . . but no, my Singer behaved perfect. And then I did something I’m really quite proud of: I figured out how to use my new mat cutting board and cut some mats. It took a while to get used to, but look:

That’s a small card by the artist Virginia Lee, of a weeping Onion Man. I found the square frame at Goodwill, and I thought, it will be too small. But with a one-inch mat, it fit the picture quite well. (I had to cut the mat twice. The trick, I found, is to use a real mat board under the mat board you’re cutting, rather than the cardboard included with your mat cutter.) Virginia gave me the card when I visited her village, in England. So I’m not saying don’t do the large things — I would not have missed my trip to England for the world. But remember to do the small ones, because those are where we mostly find meaning . . . and joy.

June 29, 2015

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

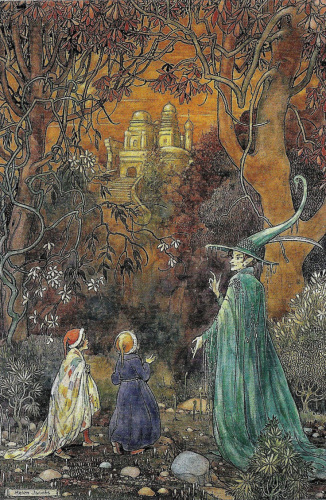

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.

I’ve decided to try something: uploading a new poem of mine every once in a while. I hope you like this one . . . And if you find that you like my poetry, you can read more in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.

Poem: Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.

I’ve decided to try something: uploading a new poem of mine every once in a while. I hope you like this one . . . And if you find that you like my poetry, you can read more in my poetry collection, Songs for Ophelia.