Theodora Goss's Blog, page 16

June 27, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Temptations and Trials

I was so busy last week that I didn’t have time to write a blog post. At the moment I’m trying to finish putting together a new short story collection, and also preparing for the Stonecoast residency, where I will be teaching for ten days. I’ve found that unless I sit down, first thing on Saturday morning, and write a blog post, I just won’t get it done. So here goes . . .

This week, I’m going to write about the temptations and trials of the fairy tale heroine. Just as a reminder, here are the steps on the fairy tale heroine’s journey:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

You can see these steps in a variety of fairy tales focused on a heroine’s journey from childhood to adulthood — a distinct subset of tales. Obviously, not all tales about heroines follow this pattern — some are not journey tales at all. I’m talking about a specific type of fairy tale, which I’ve discussed before in my posts on this subject.

The temptations and trials are a distinct phase of the fairy tale heroine’s journey, and they are two separate things: temptations, trials. Cinderella undergoes a trial when she has to become a servant in her own home. Snow White gives in to temptation when she lets the old pedlar woman in, tempted by the stay laces, comb, and apple. Trials happen to you, and must be endured. Temptations are offered to you, and must be resisted.

I’m particularly interested in the temptations in “Snow White”: as a number of scholars have pointed out, they represent the sort of mature beauty that the Wicked Queen has and Snow White is just coming into. Stay laces will make her waist smaller, accentuating her womanly figure. A comb will make her hair, in the 19th century called a woman’s crowning glory, straighter, neater. It will also allow her to dress her hair. These items will allow Snow White to become what her society considers a woman. They are temptations to feminine vanity, but also the natural desire to grow up. The apple is an important symbol in Western art and literature in two ways: it’s the apple of Eve, but also the apple of Discord with the words “to the fairest” written on it. It’s the apple fought over by Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, the apple that led to the Judgement of Paris and the Trojan War — which was of course about who gets the most beautiful woman in the world.

So Snow White’s temptations are important and symbolically freighted. The real temptation isn’t a set of laces, or a comb, or even an apple. The real temptation is becoming the Wicked Queen, with her desires and values. The fairy tale makes us wonder: how do you become a mature woman without being tempted by the image society wants you to fit, the role it wants you to fulfill? How does Snow White grow up without becoming the Wicked Queen? In her poem on the fairy tale, Anne Sexton implies that she really can’t — her world doesn’t offer her enough possibilities. She will always be trapped in the mirror, subject to its judgments. Two of my favorite scholars, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, who have written an important essay on this fairy tale, say the same thing: the tale is circular, with Snow White inevitably becoming either the Dead Queen (her own mother) or the Wicked Queen. Is there another way? The fairy tale implies there is, but at least in the Grimm version, it doesn’t give us a sense of what that other way might be.

There is another type of tale in which temptation becomes particularly important: the “lost husband” tale, such as “Cupid and Psyche,” said to be the origin of “Beauty and the Beast.” In tales of that type, the heroine is tempted to see her husband’s true form, for during the day he appears as snake or bear, or some other loathsome beast, but during the night he is a man. She gives in to temptation, and that is when her trials begin: the husband disappears, and she must go on a quest to find him again.

Trials appear even more frequently in fairy tales than temptations. There is the trial of endurance: Cinderella, Donkeyskin, and Vasilisa must all endure being treated like servants. Sleeping Beauty, after giving in to the temptation of touching the spindle, endures her long sleep. The heroine of “Six Swans” endures the trial of making shirts for her swan brothers, while resisting the temptation of speaking to save herself. And there are trials that are quests: in “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine must go on a quest to save her bear-husband from trolls. Heroines must wear out pairs of iron shoes, walk up glass mountains, outwit ogres . . . Gerda’s temptation is staying in the old woman’s flower garden, and one of her trials is facing the robbers, including the fierce little robber girl. She walks all the the way to the Snow Queen’s castle to save Kai. We can call what Andersen was writing fairy tales, even when his tales have no oral predecessor, because they honor these old templates, these paths of story. They do not always follow them, but they are always cognizant of them.

So what does this mean for us, heroines of our own fairy tales? It means that we will endure temptations and trials. I think that’s a useful acknowledgement to make. First, it allows us to anticipate them: yes, this is a temptation; yes, now I am undergoing a trial. It’s not that the universe has gone off its rails, it’s not that everything is wrong at its core. Temptations and trials are part of the pattern. It allows us to identify them: yes, I’m tempted to buy a new dress, but I need to save money; yes, I’m not happy at work, but at least for now I’ll need to endure it, because it’s helping me through school . . . that sort of thing. It allows us to formulate responses: why am I enduring temptations and trials? Well, because I’m the heroine of my own tale, and this is what happens to heroines.

Just remember that the temptations and trials are integral to the story. They are also integral to your growth. Your temptations can teach you a lot about yourself: what particularly tempts you? And why? Remember that Snow White’s temptations were also warnings: something in you wants to be like the Wicked Queen. I should point out here that temptations are not always wrong. Snow White wants and needs to grow up: her temptations are at least partly about that process of growth. Only after biting the apple can she become an adult. Sleeping Beauty is tempted by the spindle, and giving in to that temptation leads to her long sleep, necessary to her maturation. Rapunzel is tempted by the prince, and gives in rather easily! She is punished, but her punishment is also her liberation. She needs to be banished from the tower of childhood, to make her own way in the world.

And trials . . . it’s useful to remember that trials make you stronger, and smarter. Sometimes you have to endure, but sometimes you have to act, and it’s important to know the difference. Cinderella can endure, but Donkeyskin must leave her situation — her father’s incestuous desires make her home uninhabitable. Beauty must live with the Beast before she can meet her prince. During trials, you learn skills and principles that can serve you well in both fairy tales and life. The Goose Girl learns to herd geese, but more importantly learns what it’s like to be a servant. Hopefully, that will make her a better queen. Fairy tale heroines on quests learn to follow directions, be kind, keep going. These are all useful principles. And you can only really learn them the hard way . . .

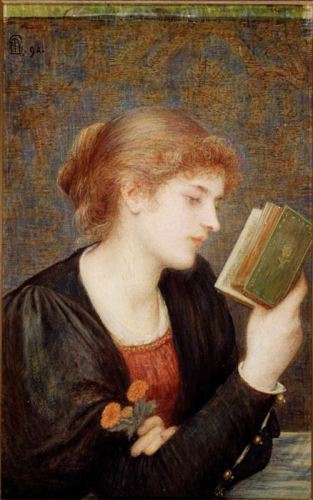

(This illustration is “The Faery Prince” by Adolf Adolf Münzer.)

Here are my previous posts on the fairy tale heroine’s journey:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

Heroine’s Journey: Leaving Home

June 13, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Leaving Home

I’m going back a bit. As you may remember, the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey looks like this:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

So far I’ve covered receiving gits, entering the dark forest, finding a temporary home, and learning to work. But I never dealt with that initial leaving or loss of home. Perhaps it’s too personal? This month, I’m putting together my second short story collection: gathering all the stories to be included, editing them, and writing a new one. That new one is probably the most autobiographical story I’ve ever written. And I’m finding it very hard to write, in part because it’s about loss. My childhood was a series of losses: when we left Hungary (I was five), I lost both my country and most of my family. Then we left Belgium, so I lost that country as well. Two languages lost: Hungarian and French. Even in the United States, we kept moving, so I don’t have a childhood friend I still keep in touch with. I lost them all.

I left my home and I lost my home, which may be one reason why fairy tales resonate with me. They are so much about leaving or losing home. Consider: Snow White leaves her home for the dark forest and loses it when she realizes the Wicked Queen is trying to kill her. Donkeyskin must leave her home because it is no longer a safe place: her father wants to marry her. The heroine of “Six Swans” is threatened by an evil stepmother, so she leaves too, for the dark forest. There are heroines who leave to be married, only to find out that marriage isn’t what they thought it would be: the Goose Girl leaves her home to be married to a king, but loses her identity in the dark forest and becomes a servant, for a while. The heroine of “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon” also leaves, to marry a bear. And that leaving is also a loss — when she does come home to visit, her mother advises her to spy on her bear husband, which leads to his disappearance and her long quest. Beauty loses her home when her father becomes bankrupt, then leaves her second temporary home to go to the Beast’s castle. Her return home is also dangerous, because she almost forgets him, almost loses him forever.

There are heroines who never leave home, but nevertheless lose it: Sleeping Beauty stays at home, but when she falls asleep and time passes, it transforms into the dark forest. When she wakes up, it is no longer the home she had: for one thing, in the Charles Perrault version, her parents did not fall asleep with her. They died long ago. She is now an adult and must fend for herself. Cinderella is famous for staying at home, but the home she knew is nevertheless lost to her when her stepmother reduces her to a servant in her own house.

Fairy tales heroines are always leaving or losing their homes. I suppose they have to: you can’t have an adventure if you’re still at home, safe, comfortable. In my class on fairy tales, I ask my students what Cinderella’s story would be like without the cruelty of her stepmother and stepsisters. Once upon a time, Ella’s father married a woman who was as good as she was beautiful, who became like a second mother to Ella. She had two daughters, also good and beautiful, and they loved Ella just as though they were her true sisters. The three girls grew up together, and when they were invited to the ball, her stepmother took her shopping and her stepsisters helped her get dressed. The prince fell in love with her, but her stepsisters were not jealous. Ella married the prince and invited her sisters to live with her in the palace. They all lived happily ever after. The End. My students laugh and are dismayed — we don’t like that story, they say. It’s boring. We can’t relate to it. No one is happy all the time.

They are asking for a heroine who suffers, because we all do, in our own ways. We can’t relate to a heroine who doesn’t. And if she doesn’t, the end becomes meaningless. Who cares if she eventually marries the prince, if she didn’t have to experience oppression and poverty for a while?

There’s a more important reason for leaving and loss in fairy tales, I think. We learn and grow through them. When Vasilisa is sent to Baba Yaga’s hut, she must learn how to fend for herself, respond to Baba Yaga’s anger, use her resources (including the magical doll her mother gave her). She shows her cleverness and also her worthiness — like Donkeyskin or the heroine of “Six Swans.” Donkeyskin responds to adversity by being clever, the heroine of “Six Swans” responds by being virtuous, self-sacrificing. That is how they earn their happy endings. Happy endings that just happen, without loss or distress, feel unearned. I think even in our own lives, we want that sense of having earned something, of having created or participated in our good outcomes. It feels hollow just to be handed “happily ever after.”

That doesn’t negate how horrible it can feel, leaving or losing home, in the real world. But one comfort fairy tales provide is the realization that only afterward can you learn and grow. That’s when the adventure begins. In “The Snow Queen,” Gerda’s quest for Kai is a journey during which she learns about the world, saves what she loves, and proves herself. That’s what we all do on our journeys, I think. Or what we should do . . . Gerda couldn’t do those things without leaving home, venturing out into a strange and dangerous world.

And fairy tales remind you that if you’re feeling a sense of loss, if you’re lost in the dark forest, if you’re surrounded by Wicked Queens or Kings who force you to spin straw into gold, it’s because you’re the heroine, and it’s a journey, and it will get better. And you’ll learn things along the way. Maybe even how to talk to animals . . .

The illustration is attributed to Florence Mary Anderson. Here are my previous posts on the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

June 6, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: A Temporary Home

I was thinking just yesterday about how much I love my apartment. It’s not large: a one-bedroom in an old brownstone in Boston. But it has four closets plus a storage space, and ten-foot ceilings. I’ve furnished it with pieces I collected over the years, some from thrift or antiques shops that I’ve repainted or refinished, some from unfinished furniture places that I finished myself. The art on the walls was painted by my grandmother or bought by me in galleries or at conventions. Nothing in it is just as it came to me: I’ve changed the drawer pulls on furniture, put new shades on the lamps. Everything in it is very much mine.

Still, it’s a temporary home. I know that I won’t live in it forever. I know there’s another home at some point in the future, already waiting for me. I hope it will be a house with a garden . . .

We all go through a series of temporary homes, which is probably why the temporary home appears in fairy tales as well. Remember the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, which I’ve been writing about? Here are the steps:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

I’ve already written about the heroine receiving gifts, entering the dark forest, and learning to work. Now I want to think a bit about that temporary home. Remember the dwarves’ cottage in “Snow White”: that’s a quintessential temporary home. So what does Snow White do there? Well, first she finds refuge. It’s a safe place to stay for a while, a place she can find another family, a place she can learn to work. But it’s not a refuge for long, because eventually the Wicked Queen does find her, and then she has to endure temptations there, in her temporary home. The temporary home is important in part because it’s not the final home, the place of rest. It’s not where happily ever after happens. It’s still part of the story.

The temporary home does not always look the same in fairy tales. In “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” the temporary home is Baba Yaga’s hut, where Vasilisa must learn to outwit the old witch. It’s a place of work and trials, but also the place where Vasilisa learns what she needs to know, becomes the person who will eventually marry the Tsar. In “Donkeyskin” the temporary home is also the place of trials: Donkeyskin or Catskin or Thousandfurs must travel to a house or castle where she works in the kitchen, performing the most menial tasks. That house or castle is her temporary home, but also the place where she meets the prince. In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine marries a bear and goes to his castle, which she thinks will be her permanent home — after all, she’s married and with her husband, right? But when she tries to discover who he truly is, she loses that home. He goes away to marry a troll princess, and she is left in the dark forest. The place she thought was her home disappears around her. The opposite happens in “Beauty and the Beast,” where the castle Beauty comes to, initially so forbidding — the place she’s convinced she’s going to die — ends up being her permanent home. But it can only become the permanent home once she accepts the Beast for who he is. She has to leave it first, go back to her family, almost abandon the Beast, and learn about generosity and love before the castle can become what it’s meant to be.

These are all different ways that the temporary home appears, aren’t they? You’ve reached the place you think is home, where you learn to do productive work and find a place to rest, but then your past catches up with you (“Snow White”). You learn to work in what you think is only a temporary home, but it turns into the permanent home when who you truly are is recognized and appreciated (“Donkeyskin”). You think you’ve found a permanent home, but then you mess up and lose it, and there you are in the dark forest again (“East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”). You find a home, and leave it, and come back to it after having learned important lessons — only then can it become your permanent home, only then can you recognize it as yours (“Beauty and the Beast”). I think we recognize these patterns in our own lives. We go through them, usually a number of times. Fairy tales are, as I’ve pointed out, reflections of human experience.

The temporary home can also be a prison, as in “Rapunzel.” It can be the place where you’re in stasis, where you can’t grow. The place you have to run away from. In “Cinderella,” the heroine’s first home actually becomes a temporary home when she’s reduced to a servant in it. It’s no longer a home for her–she has lost it without moving out of it.

Do you recognize any of these patterns in your own life? I bet you do . . .

So what lesson can we take from this part of the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey? Throughout our lives, we will go through a series of temporary homes. They may be actual houses or apartments, or metaphorical homes of one kind of another. The important thing is to recognize them as temporary. To not get stuck, or fall into despair at being in a situation when it can end. To know there is a permanent home, although it may be more metaphorical than actual. I think that permanent home is found when we feel at home, when we’re at peace. The permanent home has to be found in us, before it can be found elsewhere. And yes, we can lose it, because this is life and not a fairy tale. Our happily ever afters are always for a while. But I have friends who have found houses or careers they love, where they feel at peace, fulfilled. Where they can say, truly and with conviction, “I have come home.”

As for me? I know this is temporary, but I’m still going to hang paintings, make my apartment as beautiful as possible. I’m still going to enjoy being here, even though I know it’s only part of the journey. My temporary home is where I’m learning, building a career for myself. At the end of the day, I love coming home to my furniture, my books. It may as well be a castle, as far as I’m concerned (though a small one). It may be temporary, but it’s still a home, and I’m going to inhabit it fully.

(The illustration is by William Timlin. I’m not sure what it’s for, but it reminds me of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale called “The Shadow.” I just wrote a fairy tale of my own inspired by “The Shadow” for an anthology . . .)

If you want to read the other blog posts in this series, here they are:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

May 31, 2015

A Forgotten Poet

I’ve been working on a project of mine: Poems of the Fantastic and Macabre. It’s an online anthology of poetry with fantastical elements, from as far back as poetry has been written in what is identifiably “English.” It goes all the way from medieval ballads of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to modern poetry, by which I mean poetry of the early 20th century. Since the semester ended and I’ve had a little more time, I’ve been adding poetry, and I’ve also updated the design of the site. I’m going to keep working on it, because this is very much a long-term project. I’ll keep adding poets and poems when I can.

Recently I added a poet that particularly interested me. Her name is Ruth Mather Skidmore, and she wrote this poem:

Fantasy

I think if I should wait some night in an enchanted forest

With tall dim hemlocks and moss-covered branches,

And quiet, shadowy aisles between the tall blue-lichened trees;

With low shrubs forming grotesque outlines in the moonlight,

And the ground covered with a thick carpet of pine needles

So that my footsteps made no sound, —

They would not be afraid to glide silently from their hiding places

To the white patch of moonlight on the pine needles,

And dance to the moon and the stars and the wind.

Their arms would gleam white in the moonlight

And a thousand dewdrops sparkle in the dimness of their hair;

But I should not dare to look at their wildly beautiful faces.

Isn’t it beautiful? I found it in an anthology called Poems of Magic and Spells, which sent me back to Walter de la Mare’s anthology Come Hither: A Collection of Rhymes and Poems for the Young of All Ages, which send me back even farther: to an anthology called Off to Arcady : Adventures in Poetry, published in 1933. I very much wanted to include it, but I knew nothing about the poet. And at a minimum, I needed to know when she had been born and when she had died. I needed those dates for the table of contents.

So I went to the internet, expecting to find something. Not necessarily a biographical entry, but something . . . after all, the poem is accomplished. She was obviously a talented poet — surely she had published something else. But for the first time, researching poets for my online anthology, I drew an almost complete blank. She had not published anything else. And she, herself, appeared almost nowhere. I found exactly one reference: in a photocopy of the June 13, 1934 Vassar Miscellany News, I learned that she had graduated from Vassar that spring. Was it the same Ruth Mather Skidmore? There could not be two — the name was too unusual. So I had one small piece of information. I searched again, using various forms of her name, and came across another photocopy. This time it was a page from a local newspaper paper published in Castile, New York called The Castilian, which recorded the social activities of prominent residents. A Mrs. Ruth Mather Skidmore Remsen had visited her mother, Mrs. Ida Mather Skidmore. This must be the same Ruth? And Remsen must be her married name. I couldn’t find the exact date of the newspaper, but it had been printed sometime between 1942 and 1945. On the same page was a list of the specials at Hubbard’s Clover Farm Store: five pounds of cane sugar for 34 cents, a pint of Leadway Floor Wax for 29 cents . . . An advertisement reminded you to Buy War Bonds and Stamps. I was beginning to build a history.

So I searched again, this time for Ida Mather Skidmore, thinking that if I could finedinformation on the previous generation, I might be able to find Ruth’s birthdate. Under her mother’s name, I found an obituary for Ruth’s brother, which told me that he had been predeceased by a sister, Ruth Remsen. So I had been right, that must been her married name. I tried Ruth Remsen as a search term, but there were too many women under that name. I did find an obituary for a Ruth S. Remsen in 2002, but could it be her? I didn’t know. And then I got lucky: I found a wedding announcement for Remsen-Skidmore in The Daily Brooklyn Eagle for July 16th, 1939 — again, a photocopy. That announcement gave me the most information I had found on Ruth Mather Skidmore. Her father had been a Harry B. Skidmore of Elizabeth, New Jersey, and he was described as “the late.” She was a graduate of Vassar Collage, and had spent her Junior year at the Sorbonne. After college, she had gone on to get a Master’s degree at Teachers College, Columbia University. The day before, July 15th, she had married a man named Alfred Soule Remsen, Jr., the son of a Mr. and Mrs. Remsen who lived in Jamaica. He had graduated from the University of Michigan. There was a whole story there, one I wasn’t going to learn more about. Because there was nothing else, at least not online.

I had enough information to call the Vassar Alumni Association, which confirmed that Ruth Skidmore Remsen had been born in 1913 and had died in 2002. And that’s all I know about Ruth Mather Skidmore, the college student whose poem “Fantasy” was published the year before she graduated from college. Who was she, this girl who dreamed of the fair folk in a forest glade? Who wrote at least one fantastical poem, and then . . . nothing else? I have no idea. Perhaps there are more poems somewhere that were not published. Girls who write poetry tend to write more than one, and “Fantasy” is the product of a talented hand and mind.

As far as I can determine, given the confusing state of copyright for poems published around that time, the poem is out of copyright. (If I find that it’s not, I’ll have to remove it or find a descendant who can give me permission.) I’m glad I can reprint it, and that is after all the point of the anthology — to bring attention to poets and poems who may have been forgotten, who may not be getting the attention they deserve. And of course to highlight the long history of fantastical images and themes in poetry.

I’m pretty sure part of what I’m here for is to bring attention to the literature and writers I love. It’s not just about writing — it’s about allowing people to see the world in a different way, whether that is by writing my own poetry or researching and publishing one forgotten poet who wrote at least one wonderful poem.

I chose this painting to represent the woman poet. It’s by Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927), who would have been alive at the same time as Ruth Mather Skidmore. It’s important to remember the woman artists too . . .

May 17, 2015

Heroine’s Journey: Learning to Work

You may remember that a while ago, I wrote a series of posts about the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey. I was teaching a class on fairy tales (I just finished teaching that class last month), and I realized that there was an underlying pattern to many of the fairy tales I was teaching. I called it The Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, and in a series of blog posts I starting trying to define it. Based on those posts, I was asked to write about it for Faerie Magazine, and an article of mine called “Into the Dark Forest: The Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey,” was published in the Spring 2015 issue.

Here are the steps in the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey, as I defined them:

1. The heroine receives gifts.

2. The heroine leaves or loses her home.

3. The heroine enters the dark forest.

4. The heroine finds a temporary home.

5. The heroine finds friends and helpers.

6. The heroine learns to work.

7. The heroine endures temptations and trials.

8. The heroine dies or is in disguise.

9. The heroine is revived or recognized.

10. The heroine finds her true partner.

11. The heroine enters her permanent home.

12. The heroine’s tormentors are punished.

Now that classes are over and I have an entire summer to . . . well, catch up on my other work, I thought I would return to defining the Fairy Tale Heroine’s Journey. I want to map out the entire journey and relate it to a set of fairy tales, probably about twelve total. So this will take a while. Today, while it’s on my mind, I want to write about work.

Learning to work is a central part of many fairy tales that share this pattern. Of course we have the “Cinderella”-type tales, in which Cinderella has to cook and clean. She essentially becomes the housekeeper for her stepmother and stepsisters. In the Grimm version “Aschenputtel,” her stepmother specifically asks her to sort bowls of lentils out of the ashes before she can go to the ball. She is helped by the birds that represent her mother’s spirit, so there is an aspect of work that is passed on from mother to daughter: the mother helps the daughter out. The same thing happens in “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” where Vasilisa is helped by the doll her mother gave her. But in that story, too, Vasilisa must do housework for Baba Yaga as well as for her stepmother and stepsisters. Snow White keeps house for the dwarves. Donkeyskin works as the lowest maidservant in a kitchen. Even Beauty, who does not need to work in the Beast’s castle, works as a servant — this time voluntarily — in her own home after her father loses his fortune, rising at four in the morning to do her chores. (Madame de Beaumont had a pretty strict idea of virtue!) In “Six Swans,” the heroine needs to sew the shirts that will save her brothers and return them to their human forms.

There are some important exceptions: in “Sleeping Beauty,” work actually kills the princess, or at least puts her to sleep for a hundred years. As soon as she touches the spindle, she falls asleep. Work happens off-screen in”Rapunzel.” We are told that Rapunzel lives alone for several years with her children, which means she must be supporting them somehow, but we are not told how. Notice, however, that in the Disney version of “Sleeping Beauty,” Princess Aurora must live in a cottage in the forest with the three fairies, where she does housework. The Disney versions tend to standardize fairy tales, using parts of one to fill in narrative gaps in another. Aurora in the fairies’ cottage echoes Snow White with the dwarves. Notice also that in The Wizard of Oz, which incorporates so many of the old fairy tale structures, Dorothy must work for the Wicked Witch of the West.

Often, in these fairy tales, it is exactly the heroine’s work that leads to her final reward. Dorothy kills the witch with the water she was using to wash the floor. Donkeyskin drops her ring into the dish she is preparing for the prince, which allows him to identify her. Vasilisa wins the hand of the Tsar because she makes linen shirts so fine that he must see who wove and sewed them, and then falls in love with her beauty. When she is told that she must sew the shirts, she even says, “I knew all the time . . . that I would have to do this work.” Of course the heroine in “Six Swans” saves her brothers and proves her virtue through her sewing. In “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon,” the heroine proves her worth by washing the tallow from her husband’s shirt, winning him back from the trolls.

There’s a reason for this emphasis on work, I think. Most of these fairy tales came out of the folk tradition, and peasant women worked. They were proud of their work, and their work was seen as a mark of their worth. It proved that they were good potential wives and mothers. A good woman was also an industrious spinner and weaver, a good needlewoman. So in fairy tales, even princesses need to learn how to work. Sleeping Beauty may be an exception because she comes to us out of the romance tradition: one of the earliest versions of the story appears in the prose romance Perceforest, composed in France around the 1340s. It is the tale of Troilus and Zellandine, and in it Zellandine wakes up not when her beloved kisses her, but when one of the children she has borne while still asleep sucks a piece of flax out of her finger. Whereas folk tales were the literature of the folk, romances were often associated with the aristocracy. Perceforest is written in six books: the tale of Troilus and Zellandine came from and belonged to those who had books and could read them — those, in other words, who did not have to work. Still, there is something thematically important about the fact that Sleeping Beauty falls into her deathly sleep when she takes up what was considered women’s work — in other words, when she reaches maturity. We are still looking, here, at a woman’s journey toward adulthood and marriage.

I think the emphasis on work is an important part of these tales. Which brings us back to ourselves: our own journeys so often involve learning to work. There’s a sense in which work was written out of women’s stories around the time of the Industrial Revolution. If you look at the novels of Jane Austen, they ask the fundamental question: “Whom shall the heroine marry?” There is no interval of work in the journey from the father’s to the husband’s house. By that time, work was a class issue: working meant losing your status as a lady. Only lower-class women worked, and they were largely not the province of the novel. Jane Eyre is so revolutionary in part because it gives us a woman who learns to work before she finds her proper mate, and because she finds sustenance and self-respect in her work. It is only after going through an interval of serious work as a teacher in a poor village that Jane can come back to Rochester. But then, Jane Eyre has a deep fairy tale structure: it starts as “Cinderella,” goes on to become a “Bluebeard” story, and ends as “Beauty and the Beast.” We do, I think, both find and prove ourselves through work. Work is a fundamental part of fairy tales, as it was a fundamental part of the lives of the people who told them. So once again fairy tales can reveal an important truth:

If you want a happy ending, learn to work.

(The image of Sleeping Beauty at the spinning wheel is by Anne Anderson.)

Previous posts in this series:

The Heroine’s Journey

Heroine’s Journey: Snow White

Heroine’s Journey: Sleeping Beauty

Heroine’s Journey: Receiving Gifts

Heroine’s Journey: The Goose-Girl

The Heroine’s Journey II

Heroine’s Journey: The Dark Forest

May 3, 2015

Seeing Potential

I have a tendency to see things not as they are, but as they could become.

Last week, I bought a chair at my local Goodwill store. It took me a while to buy it. I saw it, hesitated. Bought another chair, a lovely armchair that is now in my living room, and then came back for it several days later. Why did I hesitate? Well, it looked like this:

Not very attractive, is it, in this picture? I can’t tell if it’s from the late 1970s or early 1980s. The paint was a sort of faux French country that was popular in the early 80s, but the upholstery said 70s to me. It was yellow satin, which was bad enough, but also stained. And yet, there was something. I think it was the tall rattan back, which I knew could look quite different, and the sweep of the arms. The underlying chair, the form of the chair, was better than its surface. And structurally, the chair was completely sound. So in the end, I bought it. If I ended up hating it, I would have lost $27. I could live with that.

The first thing I did was take off the cushion on the back, which was attached with buttons. I cut them off and exposed the rattan. Then, I took out the long screws that attached the seat and removed that as well, to see what I had. Which was this:

Much better, right? Now you can see the form. It’s a graceful chair, actually. A graceful chair marred by an ugly surface. So I started to paint. I have a favorite paint color for furniture: it’s called Flax, and it’s a sort of rich cream. Everything I paint with it looks fresh, modern but also traditional, and it’s particularly good on rattan. As I painted, I noticed the maker’s name on the chair: Henredon, a company that makes good, solid furniture. No wonder the chair worked so well, structurally. Henredon furniture is also aimed toward an upper middle-class purchaser who wants tradition, but in the current style. It tends to be quite expensive. That explained why the chair was such an odd combination. Underneath was a timeless form, but it was overlaid with the paint and upholstery of a particular era. In taking off the upholstery, I had exposed the form — and it was lovely.

I painted the chair, a little at a time because it was the busiest part of the semester and I didn’t always have time to eat or sleep, much less paint. But the painting was restful, a way to get away from thinking about classes and papers for a while. And now, in my hallway, I have this:

You can tell it’s not finished yet, right? The painting is finished, but I need to have the cushion professionally replaced, so for now I’ve just laid a piece of cloth on top of it. (It’s one of my favorite Waverly patterns.) I feel as though I’ve taken a dancer who was trapped in stained yellow satin and let her dance again.

The important thing, I think, is to see the potential. Not just in chairs, but in everything around you. It’s good to see what’s in front of you, but there are so many things that could still become. That’s my job as a teacher, really. To see the potential in a paper or manuscript — even more importantly, to see the potential in a student. To understand that my time with a student is part of his or her larger journey. It’s also (even more so) my job as a mother, to see both my daughter now and the woman she could become, and to help her become it. And it’s one of my own tasks, as just me. To see the potential in myself and work toward it.

One of the difficulties it that we often don’t see the potential in ourselves. We’ll see it in chairs, or in students. We know they’re not yet where they could be, we know they’re a work in progress. But we don’t see ourselves that way. We think we just are. However, we’re not chairs. Once my chair is reupholstered, it will be done. I will not change it again unless it becomes stained or damaged. It will stand in my hallway, a beautiful cream color with a flowered seat, for many years.

But I will change. There is no final stage, for people — unless it’s death, and that’s not something I need to work toward. What I need to focus on is doing, with myself, what I did with the chair. Finding my true form, the form underneath time and fashion. And creating out of that.

I know — I turn everything into a lesson! But I think even chairs can teach us, and here’s what the chair taught me.

You need to see the potential as well as the current situation. The potential is underneath, so you have to develop a good eye — for seeing the potential of a chair or of a person. You have to understand not just what is, but also what’s possible. And you have to trust your instincts. I knew, as soon as I saw the chair, what I could do with it. But I hesitated, because I had made mistakes before. I went back twice before I finally decided to buy it. We hesitate even more when we think about ourselves. We distrust our own potential, our own sense of what we could become. I need to work on that . . .

Also, we need to be willing to make mistakes. We need to assess them honestly: I could accept a $27 mistake, if that was going to happen. I would have wasted time, but at least I would have learned something. The value of a mistake is always in what we learn from it. (So when you make a mistake, make sure you’re learning.)

There’s an obvious lesson here for artists: find the potential, find what’s structurally sound and work with that. It’s what I’m always trying to do with my poems and stories. Cultivate your eye and ear so you can see it, hear it. In a really satisfying work of art, beauty is not on the surface but in the structure. And, if you think about it, that’s true of people as well . . .

April 25, 2015

A Simple Diet

I decided to write this blog post because whenever I go into the bookstore, I see books on diets, most of them filled with advice that I think is actually harmful. And whenever I go on social media, I see friends going on diets, which may or may not help them. I’ve also had friends ask me how I stay in shape, and say to me, “You must be one of those people who can eat anything she wants.” No, I can’t. I have a long history of going on diets of various sorts, back to my teenage years. None of them worked or helped me, and it took me a long time to figure out a way to eat that is healthy and makes me happy, both with myself and the food I’m eating.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you’ll know that I like to figure things out: my life is so busy that I like to figure out how to make parts of it as simple and intuitive as possible. Like cleaning, or exercise. I like to hack my own life and happiness. I want it to be easy so I can spend time on the things that really matter: my teaching and writing, my daughter and other relationships.

So how did I figure out how to maintain what I feel is a healthy weight for me, and more importantly, find a way of eating that gives me energy and makes me happy? Because if a diet (I use the word here to mean a way of eating, not a way of losing weight) doesn’t give you energy and make you happy, it won’t be your diet for much longer. It’s very hard to motivate yourself to do anything that makes you tired and unhappy — and honestly, those are signs that whatever you’re doing is unhealthy anyway.

I’ll start with my premise: no one diet is healthy and effective for everyone. We are all unique, with unique cultural and personal histories, as well as unique tastes. This is why I call foul on diet books: they tell us that everyone should be following one (their) diet. But I have a friend who was trying to lose weight, and simply could not — until she realized that she was lactose intolerant. She had to cut out dairy products entirely before she could find a weight that felt right for her. On the other hand, I’ve been told and have read that dairy products are unnecessary for adults, and that I would be healthier if I cut them out of my diet. So I tried, but it was as though my body said to me, “What do you think you’re doing?” I got sick. I was so used to following “expert” advice that it took me a while to realize what I should have understood about myself: my ancestors were nomadic horsemen. They lived on the milk from their herds for a thousand years. Without dairy products, they would not have survived. I have the body that evolved in that environment: I’m short, slight, compact. I gain weight easily, but I also gain muscle easily. I’m good at things like gymnastics and riding horses, and terrible at things like running, especially long distances. My friend and I have different bodies: mine needs diary products. One diet will not work for both of us.

So if the diet books are expensive wastes of time, how do you figure out a diet (as a way of eating) for yourself? I do think it’s important to figure it out, because we live in an environment we weren’t designed for. We evolved to eat in environments in which finding food was difficult — we had to hunt or grow it, and then prepare it. We exercised regularly simply as part of our daily lives. Obviously, we don’t live in that environment anymore. So if we want to be healthy, most of us need to be conscious about our food choices. This is how I did it, which may or may not work for you:

1. Learn about yourself.

When I realized that I kept trying different diets, none of which made me feel healthier or helped me lose weight (which was my real concern — it should not have been, but it was), I started to keep a food journal. I wrote down what I ate, when, and why. And I kept track of calories. Keeping a food journal taught me things about my body that I had not realized before. First, it made me confront the fact that my body was very precise about weight, which makes sense. After all, it’s precise about maintaining my temperature, my hormone levels . . . If I ate around 1600 calories a day, it would slowly lose weight. If I ate around 1800 calories a day, it would slowly gain weight. Between those two numbers, my weight would stay around the same. And it didn’t much matter what I ate, in terms of weight: my body cared about calories. But I also learned that what I ate mattered a great deal in terms of my energy level. White bread and sugar made my energy level rise, but then it would crash suddenly several hours later and I would be hungry again. Whole wheat bread, especially if I ate it with cheese, would give me energy for a whole afternoon. I found dark chocolate more satisfying than milk chocolate: I could eat a little and not want more. Raw sugar and white sugar affected me differently, probably because raw sugar had a more complex and therefore satisfying flavor.

And I learned about myself psychologically. I learned that I ate when I was hungry, but also when I was bored, or anxious, or depressed. I learned that I ate to give myself a treat. Food is an excellent way to deal with hunger, but a terrible way to deal with boredom, anxiety, or depression, because it doesn’t actually help. I had to find other coping mechanisms. And I found other treats to give myself: makeup, books, walks in the park. I found that in order to eat healthily, for hunger and not other reasons, I had to actually take better care of myself as a person. I also learned that I eat when I’m tired, to substitute for sleep. Also not a good idea. I still do this sometimes, but at least I recognize that I’m doing it, and when I gain weight after a week of late night snacks, I’ll know why.

I also learned about my habits, tastes, and preferences, which are just as important as learning about yourself physically and psychologically. For example, I don’t particularly care about cooking as an art, or fancy food. A bowl of pasta with sauce and cheese for dinner makes me perfectly happy. When I bake, it’s usually banana bread or brownies. Going out to a restaurant is fun as a treat, but otherwise I’m not interested in gourmet cooking. I have friends who are, and they need to take that into account when create their own preferred diets. On the other hand, I have a serious sweet tooth, and if I don’t indulge it on a fairly regular basis, I’m unhappy. So I have to make sure that my diet includes chocolate on a regular basis . . .

In a way, I hacked myself, which would have been a useful exercise even if it hadn’t led to a change in my diet and my attitude toward food.

(Breakfast: oatmeal with milk and raisins, orange juice with fizzy water, chai latte.)

2. Create your own system.

I’ve used “diet” in this blog post in two ways: as a way of losing weight, and as a way of eating. Here I mean a way of eating. Whether or not you want to lose weight is up to you, and between you and yourself. No one else is part of that conversation. But what I can say with some confidence is that losing weight as a goal does not work if it relies on changing what you eat temporarily, until you reach your “goal.” What I’m talking about is not reaching a goal but creating a new system, a way to eat that you will follow. So it needs to make you healthy and happy, to give you energy.

My diet is pretty simple. It’s a mix of grains, meats, dairy, vegetables, and fruit. The grains are whole wheat: brown rice and pasta, and whole wheat bread, because of the havoc that the white stuff wreaks on my energy levels. The meats are usually lean. The dairy is usually low fat (like 2% milk), but I don’t eat anything fat-free. I buy bags of frozen vegetables, steam them, and add butter. And the fruit is usually fresh, unless I buy frozen fruit and make something like peach crisp. I have raw sugar in my oatmeal and tea, honey in my yogurt (which I buy plain). I eat four meals a day: breakfast, lunch, snack, and dinner. The snack includes chocolate, and the dinner includes dessert (although it’s usually something like yogurt with honey, or a slice of banana bread). I try to make sure that each meal includes different types of food: grains, proteins, vegetables or fruit. I find that a combination feels me fuller and more satisfied than any food alone. Oh, and I use butter and canola oil for cooking.

I eat mostly simple, unprocessed food that I cook myself. I’m a creature of habit, so breakfast is usually oatmeal with milk and raisins, orange juice with fizzy water, and a chai latte. Lunch is usually a cheese sandwich on whole wheat bread and an apple, which I can carry with me and eat between teaching classes. Snack varies, but almost always includes chocolate as well as healthier things, like dried fruit. And dinner is usually brown rice or pasta with vegetables and meat or cheese, plus dessert. And then always a mug of herbal tea before bedtime.

I still keep a simple food journal: what, when, and calories. It’s a way of making sure that I’m conscious about my food choices, not a way of controlling what I eat. I usually stay in the 1600-1800 calorie range, because that’s where I’m not hungry, where I have lots of energy, where I feel at my best. But if I’m hungry, I always eat. There are times when I’m under stress, or very active, when I simply need more calories, or more protein, or even more chocolate . . .

And I schedule treats. Once I week, I make sure I have something extravagant that I don’t usually have — today, for example, it will be ice cream at a shop that opened downtown. A very fancy shop. When I have treats, I make them count!

(Lunch: cheese sandwich, hard-boiled egg, apple.)

3. Follow it most of the time.

This one is pretty self-explanatory. Once you’ve developed your system, one that makes you healthy and happy, one in which you don’t have to give up any food you want to eat (although you may need to eat it in moderation), just follow it most of the time. Goals are problematic because you spend most of your time feeling as though you need to reach your goal, you haven’t reached your goal, your goal is out of reach . . . A system is better because you can congratulate yourself for sticking with a system that is making you healthier and happier. And if you go away from it for a while, you can go back to it. You can’t go back to a goal, by definition.

Even better, you can build exceptions into the system. I try to follow my own way of eating, my own diet, most of the time. But if I’m at a restaurant with friends, I’ll have a wonderful meal, whatever it consists of. A burger, sushi, tapas . . . I’ll have the best meal I can. And then the next day I’ll go back to eating the way I usually do.

So that’s it, really. We live in an environment in which we’re getting conflicting messages about food all the time. We see advertisements telling us how much fun it would be to have dinner at Olive Garden, and diet books telling us that we have to cut out X, Y, or Z foods, or live like our Neolithic ancestors (while giving us completely inaccurate information on what they ate). Or cut out “toxins.” We’re caught between two damaging messages.

Sometimes I wish I could write a diet book to counteract all the diet books I see on the bookstore shelves! It would probably not sell very well, though. It would consist of these very simple messages:

We live in an environment in which to be healthy, most of us need to be conscious about what we eat. We are bombarded with messages, most of which are not helpful. You are yourself, different from anyone else. What works for me may not work for you. In this, as in everything else, you will need to find your own way. Here’s how:

1. Learn about yourself.

2. Create a system you can follow.

3. Follow it most of the time.

(Dinner: whole wheat pasta with marinara sauce and parmesan, broccoli with butter. Dessert was plain yogurt with honey.)

April 19, 2015

A Luxurious Life

I was thinking recently about how luxurious my life feels, nowadays.

And I wondered why it felt that way. After all, I’m a university lecturer. It’s not as though I make a lot of money, or spend a lot of money on things I don’t need. When I was a lawyer, I met plenty of people who lived in ways we usually think of as luxurious. They had enormous houses — often for only two or three or four people to live in. They had expensive clothes, expensive cars. They flew to exotic places on vacation. And yet I didn’t think of their lives as particularly luxurious. Their lives seemed, rather, empty and cold — like their large houses. Clichéd, like their vacations.

I certainly didn’t grow up with a sense of luxury. I grew up with a sense of lack, of the things I couldn’t have — things that often my friends could have. There was an awful lot I wanted, back then. So why, I wondered, do I have a sense of luxury now? To try and make sense of it, I listed the things that make me feel luxurious.

1. I have four closets and a storage space. It’s ridiculous, really. In one of the most expensive rental markets in the country, I somehow managed to find a one-bedroom apartment with four closets. And a storage space. My hypothesis is that luxury is having everything you need, plus a little extra. A lot extra doesn’t do anything, doesn’t increase your sense of luxuriousness. I have all the storage space I need, plus a little. And one of them is a linen closet! There are some things that are incredibly useful but feel like extras, nowadays. We wish for them but don’t expect to get them. A linen closet is one of those things. (I also have very high ceilings. In a small apartment, ten foot ceilings make you feel as though you have room — to breathe, to grow, to become.)

2. I have enough clothes to go two whole weeks without doing laundry. That’s a long time! I don’t think I ever had that, when I was a student. I was always trying to find quarters, just so I could have something to wear the next week . . . (I still feel guilty spending quarters — I default to saving quarters for laundry, even when I don’t need to.) And I have more clothes, probably, than I’ve ever had in my life. Oh, they all fit in two closets and a chest of drawers, so it’s not as though I’m becoming a fashionista or anything. It’s just that eventually (this took a very long time) I found out what sorts of clothes I loved, what suited me. So I stopped making mistakes. Also, I learned how to shop at thrift stores . . .

3. I have extra household items. I mean, if I run out of light bulbs, I have extra light bulbs! (In the linen closet.) I never had that, as a student. When I ran out of something, I didn’t have more. I had to check and see if I could afford light bulbs that week. There’s something so satisfying about having a stash of things: light bulbs, paint, glue. Plenty of trash bags. Nails to hang pictures with. And a whole stack of soap. (Also, an extra tube of toothpaste. I find the toothpaste is key.) And, just in case my watch stops, I have an extra watch!

4. I have plenty of books, but also bookshelves to put them in. Books are a necessity, of course. What’s a luxury is having specifically the ones I want to have, the ones I really need and treasure. I’ve given myself permission to give away books that don’t mean much to me, books that feel temporary. The latest bestsellers, that I read specifically to learn how they became bestsellers, for example. Gone Girl went. But I have almost everything Isak Dinesen wrote, and Virginia Woolf, and Willa Cather. I’m surrounded by the writers who mean most to me. And I have enough shelves. It’s such a luxury, having enough shelves!

5. I can buy small treats. An expensive bar of chocolate. Bubble bath (the good kind). Even sometimes an antique ring I want from Etsy, or a print that I can frame and put up on my wall. Small things, but they make me feel as though I can gather things around me, things that are delicious or beautiful. I can make them part of my life. And they change my life. I don’t agree with people who say that you should spend money on experiences rather than things. Experiences are wonderful, but I love the ring I bought, silver with marcasites, shaped like a flower. I had it resized so that it fit me perfectly, and now I wear it almost every day. That means a much to me as having gone to the ballet, or traveling in Europe. It’s a small part of my everyday life.

6. I live in a city where I can go to libraries and museums, anytime. Where the streets are lively, and there are bookstores and cafés, and a river to walk beside. There really isn’t much excuse for being bored here, because there’s so much to do. And although technically the city doesn’t belong to me, it sort of does. I don’t own Monets, but I have a museum membership, so I can walk into a room with my Monets anytime I want to. Oh, there are all sorts of annoying things about the city! Sure. Sometimes the crowds, and the expense of it. But there are wonderful things about it as well, so as long as I’m living here, I’m going to experience them all.

7. I have enough money to buy beautiful things. Like that ring I mentioned, but also flowers every week. And the next-to-cheapest tickets to the ballet. (It makes a difference in your view, whether you buy the cheapest or the next-to-cheapest. And there can be quite a big difference in price.) More than anything else, beauty gives you a sense of luxury. I think that was the main thing missing in my life, when I was growing up. I come from a practical family, and I didn’t want to be practical. I wanted to be romantic. I painted my walls pale pink, and had curtains over my bed. It’s a luxury, now, to be able to indulge my taste for beauty, for romance.

(If you want to feel a sense of luxury, that’s what I would advise: go for the small extras. You don’t need the large extras, not really. Just the small ones. A little more room, a little more beauty, a little more chocolate . . .)

That’s quite a list, I think. There are certainly things I still want in my life. (I have a list of them — I’m working on that list!) But when I sit in my living room in the morning, with sunlight streaming through the window, I realize how lucky I am. What luxuries I have now, that I didn’t have when I was younger. For so long, I approached life out of that sense of lack — I didn’t expect to have more than enough. (I barely expected to have enough.) And now I’m rich in soap, and light bulbs, and chocolate. And closets.

Here are a couple of my recent luxuries:

A cheesecake cupcake at the local cupcake shop, Sweet. It’s like a mini-cheesecake. With frosting.

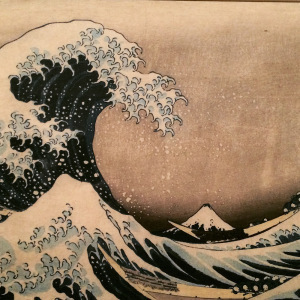

Hokusai’s The Wave, which I photographed at the museum. It’s currently having a huge Hokusai exhibit. I want to go back once the semester is over.

My brand new armchair, bought for $27 at Goodwill. Well, brand new old armchair. It just needs to be cleaned, and doesn’t it fit perfectly, right there? I’ll sit in it when I want to have tea, in the sunlight . . .

April 4, 2015

Living Hypersensitive

In the last few weeks, I’ve been overwhelmed with work, which is why I’ve gotten behind on blogging. No, overwhelmed is the wrong word — I don’t get overwhelmed with the work itself, because I’m very organized. But there have been nights when I’ve gotten home, eaten dinner, and simply fallen asleep for a couple of hours. Then I get up again and work. So what is it that overwhelms me? What is it that takes all my energy, so that at some points all I can do is collapse?

Part of the answer is people: I have so much to do with people, almost every day. For me, a truly restful day involves doing just as much work, but entirely by myself. Then I spend a lot less energy doing it.

One problem, of course, is that I’m introverted — that means people drain my energy rather than energizing me. Spending a day alone is like recharging. After time alone, my battery feels full again. But another problems is being hypersensitive. Which basically means that I have fewer boundaries protecting me from the world. Have you ever gone into a store, heard music playing, and tuned it out? I can’t tune it out. Or smelled something and then forgotten it was there? I don’t. Which is why I don’t cook with garlic . . . because the smell never seems to go away, and it never seems to stop bothering me.

A lot of people are hypersensitive in that way, but we’re in the minority, I think. And we live in a world that is not made for us, that is made for people with with a higher level of tolerance (for noise, for dirt, for all the things we can’t seem to stop noticing). It’s like living in a world made for men who are about 5’10” tall, when you’re a 5’4″ woman, which is of course my other experience of the world. (I have to stand on a stool to reach my highest kitchen cabinets. On the other hand, I fit comfortably into airplane seats, which seem to be made for people my size — despite the fact that most people are not my size.) We live in a world that is often too much for us.

So if you’re hypersensitive, what are you hypersensitive to?

1. Noises, smells, tastes, textures. The world is too loud for you. It often smells too strong, although there’s a benefit too — you get to appreciate flowers more, I think. Or the smell of baking. Being hypersensitive does have its benefits. But for me, restaurant foods are often too highly flavored. I’m perfectly happy eating a bowl of brown rice, broccoli, and peas with butter and salt. (Confession: that and a hard boiled egg is one of my standard dinners.) Some clothes are too scratchy. Do you buy clothes specifically because they’re soft? Do you cut out the tags? Then you may be hypersensitive . . . The physical world itself can be overwhelming.

2. Temperatures. I know it sounds ridiculous to people who don’t respond this way, but I notice the difference between 68 degrees and 72 degrees. When my university office is 68 degrees, my hands are so cold that I can’t write. Which means that staying in hotel rooms drives me crazy.

3. People. Do you pick up on people’s emotional states? Do you often know what they’re thinking or feeling, or about to say even before they say it? This is a useful skill if you’re a teacher. You can say things like “I think the real problem isn’t that you’re not sure how to structure this introduction, but that you’re worried about your exam. So why don’t you take the exam, and then think about the introduction? When your mind is clearer and you’re not worried about Biology, you’ll be able to set down your ideas in a clearer way.” It’s a serious problem if you live with people who are angry or depressive, because it means you pick up on their emotions. And when you can’t filter them out, and you usually can’t, they become your emotions as well.

Tip: If you’re hypersensitive, make sure the emotions you’re feeling are your own. If you’re sad, make sure it’s your own sadness, that you’re not picking it up from someone else. It’s so easy, when you don’t have those filters, to feel someone else’s feelings and assume they’re yours. The only way to tell is to go off by yourself. Go to a place where you can be alone. Now what do you feel?

4. Beauty and ugliness. If you’re hypersensitive, you need beauty, the way you need sleep or food. So make sure you get plenty of beauty. One of my best investments has been a membership to the Museum of Fine Arts. There is something so calm about an art museum . . . And if I need to see something beautiful, I can go stand in front of a Monet. Go to the symphony or the ballet if you can afford it. If you live in a city, find the parks around you. If you live in the country, plant a garden. Honestly, I would have people who are hypersensitive write themselves a prescription: “Beauty, to be taken twice daily.” (I live in the city, so I buy myself flowers; I have houseplants, and paintings on the walls. I think of decorating my space as an investment — in myself, my own productivity and peace of mind.)

Tip: Give yourself permission to avoid ugliness. Yes, I know it’s important to find out what’s going on in the world. But violence and ugliness will overwhelm you, and that doesn’t make you any more effective, does it? Figure out what you can do to help in your own corner of the world, and then do that. Don’t get into the fights that are raging all the time, unless it really is for an important moral principle. Make your message positive.

5. Stress. You will be more sensitive to stress, including the stress you generate yourself. You may have a tendency to catastrophize, to constantly imagine the worst. I do: I imagine the worst and decide how to prepare for it — it’s a way of feeling secure, which is fine, as long as I don’t then continue to imagine the worst, over and over. Because that’s not useful or healthy. The way to deal with stress is, first, to get rid of the stress if you can (change your external circumstances). But so often we can’t, and then the way to deal with unavoidable stress is to create resilience. You have to make yourself stronger. Anyway, certain kinds of stress are good for you — teaching is stressful, speaking in public is stressful, I even find signing books stressful. But they are good things for me to do, and there are also things I love about them. So how do you make yourself stronger?

Tip: You must take care of yourself. Really, you must. What makes you happy, what can you do just for you? It’s absolutely essential for you to do those things, or you’ll become depleted. You’ll collapse, the way I’ve been doing some nights. Your list will probably be different from mine, but mine includes the following: bubble baths, chocolate, reading books, flowers, going for walks. Make sure you’re getting the things you need for your soul.

Of course, also make sure you’re getting the things you need for your body: sleep, the right kinds of food and exercise, calm spaces. Soft textures. Contact with people who ask for nothing from you, who don’t take energy from you (those are the precious few).

There are both good and bad aspects of being hypersensitive. The good aspect, which is what I generally choose to focus on, is that you’re sensitive, very sensitive to beauty, to art, to music, to spring when it finally comes after a long winter. The bad aspect is that sometimes you’re too sensitive for a particular context — a rough environment, whether home or school, can send you spiraling. You need to be aware that you’re living in a world with people who respond differently than you do — not all of them, but the majority. It’s OK to adjust the world for your own needs, to the extent you can. In fact, it’s necessary if you’re going to function at your best and highest level.

You can see my tiredness in this blog post: it’s disjointed, the points still logically following one another but without the sort of flow I usually try to achieve in my writing. That’s all right. This is what I have, right now, for now. It’s the last month of the semester, and soon enough I’ll have time to rest and focus on my writing . . .

(This is me last night. Tired . . .)

March 14, 2015

Self-Doubt as Strength

I think all writers, all artists, suffer from self-doubt.

We usually think of self-doubt as a problem: notice that above, I wrote “suffer from.” Those words came out automatically, because they represent how we usually think about self-doubt: as a disease, almost. As a debilitating condition. Well, it can be debilitating . . .

I was in one of my bouts of self-doubt last week, worried about the novel I’d written, worried about whether people would “get it,” and of course like it. Worried about whether it would be published, and how, and when . . . . I’ve been doing this for more than ten years, publishing stories, essays, poems. I’ve had positive reviews, award nominations and wins. None of that stops the self-doubt. It’s much worse, I think, for younger writers — I can hear their worries, and I try to reassure them, but self-doubt is not something anyone else can fight. It’s your own personal monster. You have to fight it yourself.

But there are also some good things about self-doubt. I know, it’s counter-intuitive, but I want to argue that self-doubt can be a source of strength. It can be what makes you stronger and better. Here’s how:

1. Self-doubt can make you work harder.

I know, this isn’t always true: self-doubt can also lead to giving up. But doubting my own talents and abilities has driven me to work harder, in pretty much everything I’ve done. Study harder for the exam. Prepare harder for the class. Practice more. I sometimes see this among young writers as well: they doubt themselves, and that doubt spurs them on rather than stopping them. They don’t know if they’re any good, so they try to get better. They don’t know if a story works, so they think about it more, revise it more readily. They put in the hours.

Of course, you can put too much work into something: there comes a time when studying harder is counter-productive, when a story should not be revised further. You need to know when to stop. But I’ve seen a lot of people stop too soon. I’ve seen that more often than the opposite — people wanting something and not putting the work in, assuming they’ve done enough. Sometimes they have so much confidence in themselves and their talents that they feel as though they don’t need to put in the work. And they don’t do as well.

So self-doubt can be a good thing: it can make you work harder to get what you want.

I’ve read that women tend to apply for jobs they know they are fully qualified for, while men tend to apply for jobs they are mostly qualified for — they don’t wait until they are fully qualified. I’m sure this is partly because women doubt themselves more in general, although I hesitate to make generalizations based on gender. I have male friends who are writers and artists, and many of them suffer from self-doubt too. But we do live in a culture that fills women with self-doubt in a way it doesn’t for men. Are you pretty enough? Are you smart enough? These are questions women ask themselves from the time they are teenagers. Our default image for qualified is still male. My point here isn’t to emphasize the gendering of self-doubt but to say that we’ve all known situations in which someone (male or female) got in on bluster, on a show of self-confidence, without necessarily being qualified. That is generally a bad thing. The saying “fake it till you make it” is a disaster if you’re taking about anything that really matters, like brain surgery or making cupcakes. Or, you know, art. (Because fake art is a horrible thing. Like a great big flowery Jeff Koons puppy.)

2. Self-doubt can make you hold yourself to a high standard.

Self-doubt means you judge yourself more harshly, which can be a bad thing. It can lead to despair and depression. But it can also make you hold yourself to a high standard, perhaps a higher standard than society gives you. Society, after all, gives us only the standard of a particular time. As artists, so often we have to create our own standard, out of what we believe to be the best — out of what particularly speaks to us. Yes, this is an impossible standard. I’m never going to write like a combination of Virginia Woolf and Isak Dinesen and Angela Carter. Even if I could, it would be incoherent. I have to find my own way, my own voice.

But I doubt myself and therefore I try for the best. What I aim for may always be beyond my reach, but at least I will know the distance between what I am doing and where I want to go. And I won’t say “this is enough, this is good enough.” I will say “this is the best I can do for now,” because otherwise, honestly, I would never publish anything. But I will try for better. I will do the next thing, because who knows, the next thing might be it. Or the thing after that . . .

3. Self-doubt gives you a sense of humility.

The hardest student to teach is the student who is convinced that he or she already knows how to write. Often, it’s a student who got As on English papers in a high school that was not particularly rigorous. A student who was taught to use large words without understanding their precise meanings, who was rewarded for obfuscation, for “sounding academic.” For this sort of student, you must first breach the wall of self-confidence, and it can be a pretty thick wall. You must show him or her why that sort of writing isn’t actually very good. And you must do it kindly, or you will encounter the natural resistance of wounded pride. (Often what it takes is pointing to a sentence and saying, “What do you actually mean here?”)

A student who doubts his or her own abilities will listen to you, will learn what you have to teach. So if you have self-doubt, you tend to be a good student. You tend to think that if you’re not learning, the problem isn’t the teacher, but you. (The problem is sometimes the teacher, but blaming the teacher is seldom useful. More useful is taking what you can from the teacher, despite his or her limitations. A good student can learn from almost anyone in almost any situation.)

We don’t value humility very much in our culture. We value pride, even when it’s just a show of pride. Even when it’s just bluff. But I think great artists tend to have great humility, because they know how hard the road is, how much they’ve worked, how fortunate they’ve been. (Except Picasso. And maybe Salvador Dali. If they had humility, they didn’t show it.) Great artists have pride too, of course — in what they’ve accomplished. But they always seem to be looking for the next thing to work on. What they’ve already done never seems enough . . .

4. Self-doubt means you’re already vulnerable, without having to work at it.

There seems to be an entire industry devoted, nowadays, to telling people that they need to be more open, more vulnerable. I suspect it’s an industry founded by self-confident extroverts. I know lots of people who don’t need to be more vulnerable. Instead, they need to build boundaries, to say no more often. I’m one of them. People who have self-doubts are usually already open to the world, to its judgments of them. They aren’t very good at shutting the world out.

In my family, we have a generation (me and my brother) of hypersensitive, introverted kids. Where we came from, I don’t know, because the rest of my family isn’t like that. But it’s obvious how differently we deal with the world. To the extent that vulnerability is a good thing (it’s not always), we have it. We don’t need to work on it. So, you know, we don’t need to take courses with people who’ve been on Oprah, which leaves more time for other things. Like maybe writing.

My central point here is that self-doubt can be a weakness: it can keep you from doing your work. But you can also redefine it as a strength. If you doubt yourself, that means you’re someone who holds yourself to a high standard; who has a sense of humility, of your own limitations; who is vulnerable and open to the world. Those are all good things. Self-doubt can lead you to work harder.

Which is how I dealt with my own self-doubt: I wrote a poem. When in doubt, write poetry . . .

(Well, more practically, since I’m worried about the novel, I laid out a new writing schedule for myself. And yes, I wrote a poem, but I’m also working on a story. Above is me working on the story.)