Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 6

November 22, 2024

Can’t all Canada agree to like Montgomery (except her poetry)? by Audrey Loiselle

Last June, I attended the Lucy Maud Montgomery Institute’s biennial conference at the University of Prince Edward Island for the fourth time, having previously participated once as an audience member and thrice as a presenter, so infectious is the atmosphere at this academic yet convivial event. For the first time, though, I drove there, leaving the Eastern Townships of Québec at dawn to cross the Canadian-American border into Maine and then back into New Brunswick before cruising along the Confederation Bridge and heading into Charlottetown. When I emerged from the car after ten hours, I felt both exhilarated and exhausted; I couldn’t believe just how close and how far Maud’s land turned out to be!

Once more, with (even more) feeling : PEI 2024

(From Sarah: This is the tenth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

This contradiction in terms mirrors my long-term relationship with the venerable English-Canadian 20th-century writer as a millennial French-Canadian reader and translator. For my rapport with Montgomery has demanded constant reassessment and reframing throughout the years, as I transitioned from the transfixed teen who repeatedly read her (mostly) cheerful fiction in French translation to the college student who tackled her far more depressing private writings and eventually found my way into the literary and scholarly circles devoted to her. Meeting intellectuals who saw Montgomery and her works as complex entities worthy of study was instrumental to my decision of making her and her semi-autobiographical Emily trilogy the focus of my master’s thesis in literary translation at a francophone institution. However, I found myself there surrounded by people who tend to disparage Montgomery on principle, because they associate her—not unlike Jane Austen—with a genre accused of excessive banality and sentimentality, but also, and more grievously, with an “English” sense of superiority which stoked anti-French prejudices in a (hopefully) bygone era in Canada.

With fellow housemates and scholars. From left to right: Irina Levchenko, Susan Erdmann, Leïla Matte-Kaci, me (Audrey Loiselle), and Laura Leden.

My co-students’ and professors’ reservations are not entirely unfounded. Montgomery was not above resorting to tired plots or abusing purple prose at times, especially in the short stories which she peddled to mass-market magazines and airily dismissed as “potboilers.” And though Kevin McCabe posited that “[w]hen viewed in the context of her times, Maud’s racism and xenophobia are not earth-shattering,” Montgomery undeniably held classist views and did not paint French-Canadian characters in a particularly flattering light in her books. In the Anne and Emily series, Acadians from the “Creek” or the “Pond” briefly feature as ungainly farmhand or household help, spreading gossip and germs throughout respectable Anglo-Canadian homes and communities. Though some shine briefly as bearer of good news (Pacifique Buote in Anne of the Island), sympathetic listener (Judy Pineau in The Story Girl), or gifted fiddler and storyteller (Lazarre in Magic for Marigold), uniformly sunburned and black-eyed Acadians are mostly met with mistrust and contempt in her novels. There is overall little to counter Caroline E. Jones’ criticism that Montgomery’s French-Canadian characters are “flat constructs . . . never written as round, well-developed individuals who contribute to the storyline and . . . entirely lack[ing] cultural and symbolic capital.”

Despite these considerable drawbacks, I persisted in believing and in wanting to demonstrate that modern French-Canadian readers and translators ought to pay Montgomery some attention. I plied my unfortunate director, who probably wished I were working on fresher, less problematic voices, with weighty articles like Mary Henley Rubio’s seminal Subverting the Trite, to wear down her reticence. I stooped to embarrassing emotional pleas to get fellow students to “try anything from Montgomery, really” (save her poetry—that would have been both cruel and counterproductive). One eventually caved in—possibly to stop me from bringing up the topic at every party—but insisted on being given a specific title. I picked A Tangled Web, as it ranks among my personal favourites, but also because “it is a novel about negotiating changes in perspective,” as UPEI’s former president and L.M. Montgomery Institute cofounder Elizabeth Epperly aptly commented at the 2024 conference focusing on L.M. Montgomery and the Politics of Home.

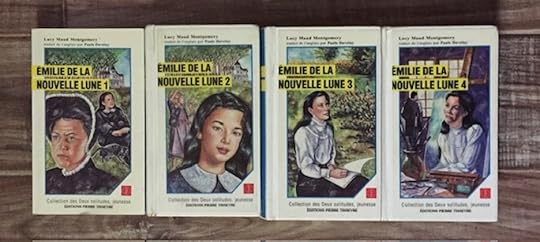

The French-Canadian translation of the Emily trilogy by Paule Daveluy

Published in 1931, before plummeting stocks and dwindling sales due to the Great Depression forced Montgomery to fall back on safe bets like Anne, A Tangled Web magnifies for me her strengths and weaknesses as a writer. Its brilliancy lies not in its highly contrived plot, but in its complex characterization and in its narrator’s cutting yet compassionate outlook. It is a heartening, humorous tale which, because of its theme and scale, appears to be the mature “book portraying the life among the big clan families of the Maritimes” that the author long wanted to write (Letter to Ephraim Weber, November 16, 1927). It is not an unmitigated success, though. Montgomery sometimes seems at sea with its huge cast; inconsistency with names and timelines which would mar The Blythes Are Quoted, the last manuscript that she submitted before her death in 1942, start to crop up. And there is of course that infamous ending with a racist slur which, while ostensibly “part of a larger strategy of letting the flawed and prejudiced characters speak for themselves,” would prevent the book from being brought up at many Canadian institutions nowadays (Benjamin Lefebvre, introduction to A Tangled Web).

But just as English-language initiatives like the L.M. Montgomery Readathon spearheaded by Andrea McKenzie allow us to reevaluate and reenjoy Montgomery’s works by replacing them in their historical context while discussing them from a modern perspective, I dream of finding a way to make this vital Canadian author appealing to my French-speaking compatriots, starting with my fellow translators. For after all, aren’t translators instrumental in shaping the language and, in collaboration with publishers, in swaying the reception of English-Canadian voices by French-Canadian readers? Could practitioners of this often feminine, domestic-focused and devalued trade somehow relate or even sympathize with Montgomery’s keen awareness of the rigid expectations placed on her by the public and publishing houses, her customary resigned willingness to play along and her occasional fit of frustration when even that failed to bring her consideration? Recent foreign publications of biographical material on Montgomery, retranslations of her fiction and studies undertaken by translation scholars from Sweden, Finland, Japan, Russia, Brazil, France and Poland give me hope in this endeavour. Here’s to figuring out how to make the celebrations truly coast-to-coast before reaching Montgomery’s 175th or 200th anniversary!

Works Cited

Epperly, Elizabeth. “Montgomery at Home: Two Caves and a Book.” Keynote address at the L.M. Montgomery and the Politics of Home Conference, June 22, 2024, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PEI.

Jones, Caroline. “‘Nice Folks’: L.M. Montgomery’s Classic and Subversive Inscriptions and Transgressions of Class.” Anne Around the World: L.M. Montgomery and Her Classic. Ed. Jane Ledwell and Jean Mitchell. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013. 133–46.

Lefebvre, Benjamin. Introduction to A Tangled Web by Lucy Maud Montgomery. Toronto: Dundurn, 2009. 9–18.

McCabe, Kevin. “Ethnic Minorities in L.M. Montgomery’s Writing.” The L.M. Montgomery Album. Ed. Alexandra Heilbron. Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1999. 461–462.

Montgomery, L.M. After Green Gables: L.M. Montgomery’s Letters to Ephraim Weber, 1916–1941. Ed. Hildi Froese Tiessen and Paul Gerard Tiessen. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Rubio, Mary Henley. “Subverting the Trite: L.M. Montgomery’s ‘Room of Her Own.’” Canadian Children’s Literature / Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse 65 (1992) 6–39.

Audrey Loiselle holds a B.A. in French studies (Translation) from Concordia University in Montréal and is pursuing a master’s degree in Comparative Canadian Literature at l’Université de Sherbrooke while working as a translator for the federal government of Canada. She presented papers at the 2018, 2022 and 2024 editions of the L.M. Montgomery conference at the University of Prince Edward Island in Canada, and at the L.M. Montgomery Conference at Reitaku University in Japan in 2019. She also published an article on an eventual French translation of The Blythes Are Quoted in Les Cahiers Anne-Hébert (vol. 18, 2022). In August 2024, she presented a paper on the first French translation of Emily of New Moon at the Children’s Literature and Translation Studies conference in Stockholm, laying the foundation for the thesis that she hopes to complete someday.

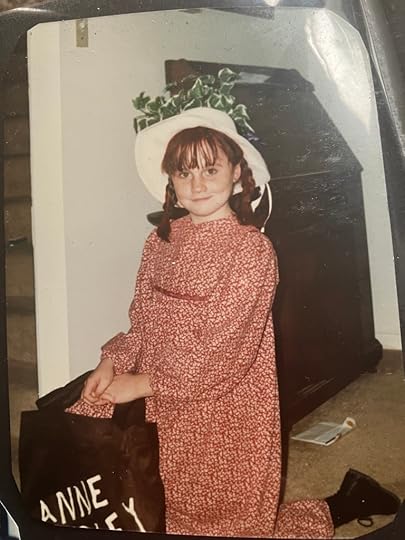

Audrey contributed the photos above, along with these three photos. She says, “Trips to PEI are opportunities for family pilgrimage with my daughters Ariane and Flavie.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “Books and Chums,” is by Trinna S. Frever.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

An Emissary of Laughter: L.M. Montgomery and the Saving Grace of Humor, by Liz Rosenberg

L.M. Montgomery and Emily Carr, Worshippers of the Woods, by Marianne Ward

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Audrey Loiselle, 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 20, 2024

An Emissary of Laughter: L.M. Montgomery and the Saving Grace of Humor, by Liz Rosenberg

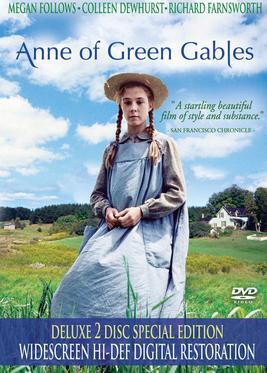

In a video interview, actress Colleen Dewhurst (who memorably played Marilla Cuthbert in the Canadian “Anne of Green Gables” series) observed that “humor is the great introducer. If you find you have the same sense of humor you feel you’re on less dangerous ground.”

(From Sarah: This is the ninth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

The first time I met my husband on our first date, I thought, “He is a perfectly nice man, but he will always be a stranger.” Then he told a funny story that made me laugh, making himself the butt of the joke—and that was the beginning of familiarity, safety, intimacy.

Dewhurst connects her observations about humor to L.M. Montgomery’s life and writings. Here is her quote in full:

“The term kindred spirit which is used so much throughout Anne of Green Gables is that search where we recognize each other—we don’t know why we do. There can be ten people in a room and there’s one that is recognizable and you both realize it when you recognize one another—often through humor. Because humor is the great introducer. If you find you have the same sense of humor you feel you’re on less dangerous ground, and you begin to move closer.”

Perhaps this helps to explain why readers of Montgomery’s books—kindred readers—feel passionate about her work, and connected to one another in mysterious but deep ways. A sense of humor, as Montgomery explains in her first and most famous novel, “is simply another name for a sense of the fitness of things” (Chapter 7).

That initial moment when we first glimpse a sense of humor in the rigid, excessively tidy and dour Marilla Cuthbert is the moment any well-attuned reader breathes a sigh of relief. And the glimmer of this miracle occurs within two pages of their first meeting. Poor Anne has just announced that the mix-up that drives the plot—a girl orphan has been sent to the Cuthberts rather than the expected boy—is “the most tragical thing that ever happened to me!” (Chapter 3)

In response, “Something like a reluctant smile, rather rusty from long disuse, mellowed Marilla’s grim expression.”

Of course, the situation is tragic. Anne has been shunted from borrowed house to house all of her life, in a state of servitude. She has lived in unwelcoming foster homes and in an “unromantic” orphanage and made the best of things—but she has never known full acceptance or family. When she arrives at Green Gables, she believes she has found a real home at last. Instead, Marilla greets her at the door with a cry of disappointment and dismay: “Well, this is a pretty piece of business!” (Chapter 3)

The reception is blood chilling—any reader with a heart feels it at once. But Anne’s melodrama and mispronunciation also contain a touch of the ludicrous. We who understand “the fitness of things” appreciate that sorrow and hilarity travel hand in hand—and so does Marilla.

Humor is a particular honed skill, and not even saints possess it. Marilla’s brother Matthew Cuthbert appreciates Anne’s spirit right away—his heart unquestioningly goes out to Anne—a fellow outsider at the edge of society. Theirs is an unconditional love and friendship from the start.

Marilla is a tougher sell. She provides something quite different but essential for Anne. With a shared sense of humor comes understanding—that’s what Colleen Dewhurst meant. Montgomery often said that she knew her own grandmother Lucy loved her, but there was “no understanding between us.”

If humor can bring perfect strangers to feel as if they are secret friends, then the absence of such a bond creates a deep, hungering loneliness. Maud “met” her best friend, Frede, only after many years of knowing her as a much-younger cousin. But one night they stayed up till dawn, talking, confiding, and making each other laugh. Montgomery never felt closer to anyone than she did to Frede, her soul-mate, friend, and compatriot in laughter and tears. The times they spent together at Park Corner, where Frede lived with her merry siblings, mother, and father, were “the jolliest times” of Maud’s young life. Like many sad children, she loved to laugh.

Humor plays a great role throughout Montgomery’s books—partly because Maud had a wonderful sense of humor—and partly because she was greatly in need of its balancing power. Her life was more tragic than comic. Maud’s mother died when Maud was a toddler, and by the time she was five, Maud had been effectively orphaned when her beloved father wandered off to the far ends of Canada in search of some way to make a living. She was raised thereafter by her grandparents, an unwilling older couple, who, like Marilla Cuthbert at the start, grimly agreed to “do her duty by the child.”

Maud’s grandparents were long past child-rearing age by the time they inherited this big-eyed, bright, moody, sensitive little girl. Their youngest daughter Emily would soon marry and leave home. Emily’s wedding was the first—and the last—occasion of merry celebration in that house where Maud grew up. Like her fictional creation, Anne, she was viewed as a burden and an outsider. No wonder she was so imaginative and funny—how else could she have survived?

I used to teach a class each fall on Literature and Jewish Humor and I learned that the funniest people were also often the saddest. In a class full of laughter and spontaneous comedy routines, invariably at least one student would end up in a breakdown on our city’s psych ward. I grew accustomed to visiting these students of comedy, flowers in hand. This might have seemed funny if it hadn’t been so heartbreaking. And it would have been entirely heartbreaking if it hadn’t also, in its weird way, also been funny. (They all recovered, thank heavens.) Humor is a potent form of self-medication. It is best to become adept at it, if one is to survive. Maud became a champion.

Her entire body of work has been often hailed by critics as uplifting. The term has been used both to praise and to dismiss her. One of her novels—by no means her cheeriest—was distributed to Canadian soldiers in World War One, to comfort them. The merits of her children’s books were debated earnestly by Sunday Schools and librarians who sometimes embraced, sometimes censured them for their “frivolity” and “irreverence.” One admiring contemporary reviewer wrote that her work “radiates happiness and optimism.”

If they had known, Maud wrote, the distress and at times the despair in which she had lived, creating those sparkling books, they would have wondered how she was able to write at all.

But she knew what she was about. She understood that one of her callings in life as in art was to delight the spirits of others. In this she succeeded more brilliantly than I think she ever knew. “Thank God,” she wrote in her journal on October 15, 1908, “I can keep the shadows of my life out of my work. I would not wish to darken any other life—I want instead to be a messenger of optimism and sunshine.”

As a creator of comedy, Maud showed sheer genius. She was a brilliant mimic and satirist with a lightning-fast wit; told funny stories as well as writing them, and created unforgettable comic characters. Sometimes she startled herself into fits of laughter. She lived and wrote largely inside in her own mind, inventing and revising stories. A household member one day observed Maud suddenly come to a halt on the stairs, to shout with surprised laughter, “that’s what I’ll do! That’s just what I’ll do!” And she rushed off to write it down (quoted by Mary Henley Rubio in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings [2008]).

One might argue that her work only falters when it loses its sense of humor. Or perhaps she lost her “sense of the fitness of things” once the work had slipped away from her control. Pat of Silver Bush, Rilla of Ingleside, and Anne’s House of Dreams strike me as some of the least successful—and least funny of her novels. But these are exceptions rather than the rule. From Anne’s famous misadventures with green hair dye to “setting Diana [her best friend] drunk” (Chapter 27); in a host of fictional mishaps, witticisms, jokes, literary slapstick, sly jabs, and brilliant characterizations, Montgomery exhibits comic genius of every type. It is almost impossible to stay sad or anxious while reading her words.

Montgomery gratefully expressed her own debt to books and writers countless times. She thanked the late author Washington Irving in public and in private for the joy of his enchanting tales. At the end of a hard afternoon she wrote, “Washington Irving, take my thanks. Dead and in your grave, your charm is still potent enough to weave a tissue of sunshine over the darkness of the day. I thank you for your ‘Alhambra’” (April 12, 1903). She would undoubtedly be thrilled to hear that she herself has become an emissary of delight to millions of grateful readers all over the world.

Quotations are from the Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Liz Rosenberg is the author of more than a dozen novels, books of poems, children’s books and non-fiction, including her biography of L. M. Montgomery, House of Dreams (Candlewick Press) which won a top 10 Goodreads History Books award. She teaches half-time at Binghamton University, and lives part-time in coastal Connecticut. Luckily, her son Eli Bosnick is a professional comic. Her daughter Lily is a semi-pro smiler. Liz sent me this photo of the two of them:

Over the past couple of weeks I’ve been looking for ways of capturing late afternoon light, even on cloudy days, and I took the photos of the autumn leaves that appear earlier in the post.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “Can’t all Canada agree to like Montgomery (except her poetry)?” is by Audrey Loiselle.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

L.M. Montgomery and Emily Carr, Worshippers of the Woods, by Marianne Ward

Discovering Anne of Green Gables in Tel-Aviv, by Nili Olay

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Liz Rosenberg 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 18, 2024

L.M. Montgomery and Emily Carr, Worshippers of the Woods, by Marianne Ward

One of the lasting gifts of L.M. Montgomery’s writing is its exaltation of the natural world, particularly trees and woods, for which Montgomery and her characters feel great reverence and in which they find intimations of the divine. In this I find her a kindred spirit of iconic Canadian painter Emily Carr, Montgomery’s contemporary, who was also an author. One might argue that the reverence Emily Carr (December 13, 1871 – March 2, 1945) had for the forests of British Columbia was akin to what Lucy Maud Montgomery (November 30, 1874 – April 24, 1942) had for the woods of PEI. Each desired to somehow capture and depict the divine manifest in nature—one in paint, the other in words.

(From Sarah: This is the eighth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

In the opening chapter of Montgomery’s beloved first novel, we learn that before Anne Shirley left Nova Scotia for PEI, she was told that Green Gables had “trees all around it.” She tells Matthew this made her “gladder than ever. I just love trees.” When, in Chapter 7, Marilla tells Anne she must kneel and say her prayers if she wishes to live at Green Gables, Anne says, “Why must people kneel down to pray? If I really wanted to pray I’ll tell you what I’d do. I’d go out . . . into a deep, deep woods, and I’d look up into the sky—up—up—up—into that lovely blue sky that looks as if there was no end to its blueness. And then I’d just feel a prayer.”

As though building on Anne’s simple declaration of love for trees, in Emily Climbs, the second book of Montgomery’s more autobiographical Emily series, Emily Starr says, “I regard trees with something more than love—worship” (Chapter 19). According to the Reverend Mr. Dare in Emily of New Moon, to worship trees is entirely appropriate. Emily tells Mr. Dare that she was worried because although she knew she ought to “love God better than anything,” there were things she “loved better than God”: “flowers and stars and the Wind Woman and the Three Princesses [Lomabardy poplars] and things like that.” Mr. Dare smiles and tells her, “But they are just part of God, Emily—every beautiful thing is” (Chapter 17).

It is clear to me that Montgomery feels as Carr does: that God, or what I’m calling “the divine,” is to be found in the beauty of the natural world. Robin Laurence says that “For [Carr], God resided not in ‘stuffy’ churches but in the soaring cathedral of the British Columbia rainforest, in the sepulchral shade of its densest recesses and in the spectral light of its clearings. She found God, too, . . . beneath the radiant canopy of the sky.” Laurence continues, “the natural world is, ultimately, where [Carr] found her sense of spiritual connection” (“Emily Carr and the Theatre of Transcendence: High Spirits,” Canadian Art [June 21, 2012]).

Above the Trees, by Emily Carr (Public domain, via Wikiart Visual Art Encyclopedia)

Doesn’t that sound exactly like Anne and her description of the “deep woods” and “lovely blue sky” where she would “just feel a prayer”? That description of Anne’s could be applied to any number of Carr’s profoundly moving paintings of deep woods and blue sky, in particular Above the Trees (1939). And just as Montgomery describes “The Avenue” of apple trees Anne and Matthew pass through on the drive to Green Gables (Anne’s White Way of Delight) as being like “a cathedral aisle” (Chapter 2), Carr titles one of her paintings of the deep woods, Cedar Sanctuary (c. 1942). Both women, Montgomery and Carr, believed that worship of the divine is not to be constrained to churches and that trees and the woods provide hallowed ground, just as is found in the sanctuary of a cathedral. Montgomery makes this explicitly clear in Chapter 27 of Anne of the Island: “‘The woods were God’s first temples,’” quoted Anne softly. “One can’t help feeling reverent and adoring in such a place. I always feel so near Him when I walk among the pines.”

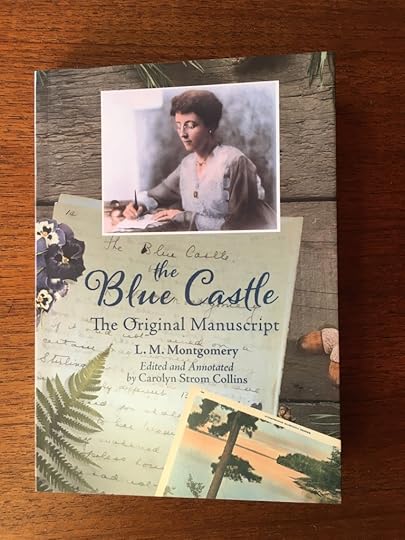

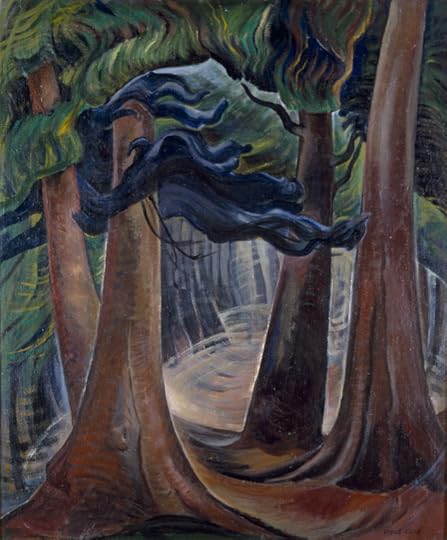

In Montgomery’s 1926 novel The Blue Castle, Valancy Stirling admires the writings of the (fictional) author John Foster, who encourages “reverent visits” to the woods: “if [the woods] know we come to them because we love them they will be very kind to us & give us such treasures of beauty & delight as are not bought or sold in any market place. For the woods . . . hold nothing back from their true worshippers. We must go to them lovingly, humbly, patiently, watchfully, and we shall learn what poignant loveliness lurks in the wild places & silent intervals . . . what cadences of unearthly music are harped on aged pine boughs or crooned in copses of fir” (Chapter 3). One could imagine Carr being inspired by this passage when she painted Among the Firs (1931). Both Foster/Montgomery and Carr knew that reverent worshippers will find a kind of heaven in the woods.

Among the Firs, by Emily Carr (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

LMM scholar Sarah Conrad Gothie, one among the many who have written about Montgomery’s love of nature, talks about Montgomery’s “belief in nature as a site of transcendence.” She says, “Montgomery’s reading of William Wordsworth, John Keats, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and others foregrounded for her the spiritual, creative, and . . . healing qualities of the natural world” (“I Would Rather Lose Everything Else I Possess: Love of Nature and L.M. Montgomery’s Intuitive Wellness Strategies, 1901–11,” Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies online [January 12, 2024]). Similarly, Emily Carr scholar Lisa Baldissera says, “Carr’s deep-rooted spirituality was drawn initially from her Protestant origins and later enriched by theosophy, Hinduism, and the transcendentalism of American poet-philosophers such as Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. All these influences led her to invent new forms of artistic expression—evident in her late paintings, such as Blue Sky 1936—to reflect her creative vision of the B.C. landscape and what she saw as its spiritual and elemental force” (Emily Carr: Life & Work [2015]).

Though Montgomery and Carr never met, being separated by the entire continent, and I’ve found no indication that they were even aware of one another’s work, I’d like to think that these two remarkable Canadian women artists, with their profound love of the natural world—trees and woods in particular—would have recognized in one another a kindred spirit. That their birthdays were just two weeks apart, though separated by three years, is as wonderful a “coincidence” as that of Anne’s and Diana’s birthdays being separated by only a month.* (Carr and Montgomery also died at the same time of year, the former in March, the latter in April, also three years apart.) The inscription on Carr’s gravestone—Artist and Author, Lover of Nature—could, but for the first two words, also be applied to Montgomery. There is much scope for the imagination in pondering how L.M. Montgomery and Emily Carr might have reacted to each other, and their artistic output, had they ever crossed paths in the woods.

Quotations are from the McGraw-Hill/Ryerson editions of Anne of Green Gables and Anne of the Island (first Canadian paperback edition, 1968), from a boxed set of the first three Anne books, packaged as a “Triple Treat” “gift pack” by “the Charlottetown Festival’s musical of Anne of Green Gables”; the Seal Books McClelland-Bantam edition of Emily Climbs (1983); the McClelland and Stewart, New Canadian Library edition of Emily of New Moon, with an Afterword by Alice Munro (1989); and the Nimbus Publishing edition of The Blue Castle: The Original Manuscript, by L.M. Montgomery, edited and annotated by Carolyn Strom Collins (2024).

Marianne contributed the photo of the autumn trees and blue sky that appears at the beginning of the post. The photo of Marianne, below, is by Nicola Davison of Snickerdoodle Photography:

Marianne Ward is a freelance book editor who has the distinct honour of being one of the few living editors to have worked on two of LMM’s manuscripts, as proofreader for Anne of Green Gables: The Original Manuscript and editor of The Blue Castle: The Original Manuscript (both transcribed and annotated by Carolyn Strom Collins and published by Nimbus Publishing, in 2019 and 2024, respectively). She’s thrilled to be adding a third book to the list: twenty-seven rediscovered stories by Montgomery, collected by Collins and slated for publication by Nimbus in fall 2025. Marianne (with an “e”) was born in Charlottetown, PEI, the year Anne of Green Gables – The Musical premiered there, and Kevin Sullivan’s beloved TV adaptation of the novel premiered on her twentieth birthday, which confirms for her that she and Anne Shirley are deeply connected.

Marianne’s childhood copy of Anne of Green Gables

*Coincidentally, Marianne’s birthday falls in between Carr’s and Montgomery’s. Marianne is grateful to live and work in beautiful Mi’kma’ki (the part known as Nova Scotia), loves trees, and worships the woods. This is her first-ever blog post.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “An Emissary of Laughter: L.M. Montgomery and the Saving Grace of Humor,” is by Liz Rosenberg.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Discovering Anne of Green Gables in Tel-Aviv, by Nili Olay

L.M. Montgomery’s Poem “The Gable Window,” by Hughena Matheson

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Marianne Ward 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 15, 2024

Discovering Anne of Green Gables in Tel Aviv, by Nili Olay

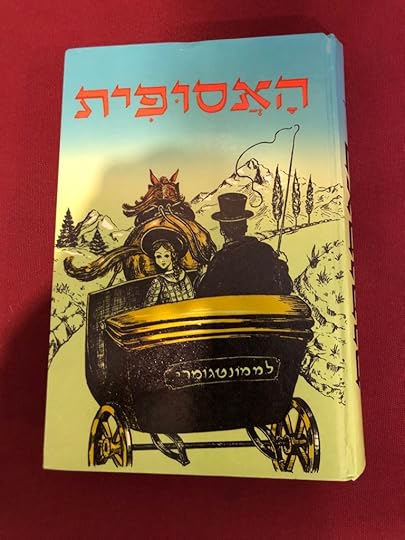

I was born in Tel Aviv, Israel. When I was nine years old, sick in bed, my mom gave me a book called The Orphan, in Hebrew. She had read it in Poland, in Polish, when she was my age and remembered it fondly. Anne of Green Gables had been translated into Polish in 1918, three years after my mom was born. I just loved this book—read it and re-read it.

Green Gables Heritage Place

(From Sarah: This is the seventh guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

A couple of years later when we were emigrating to the U.S., my mom tried to sweeten the idea of the move by promising me that when I learned English, I could read the other books in this series. I was not happy about leaving my extended family and friends, leaving most of my books behind, and going to a strange country. I was allowed only six books to emigrate with me and of course, my copy of The Orphan came with me to Chicago and was read and re-read many times. It was my comfort in the strange, new and cold environment.

The Orphan

When I learned to read English, I looked for a book called The Orphan in the library—no luck. I asked friends but they had never heard of it. It was not until a few years later, when I learned how to do library searches on authors, that I figured out that The Orphan was called Anne of Green Gables in English. What joy! I took out the rest of the “Anne” series from the library. At that time, in the late 1950s, most of L.M. Montgomery’s books were out of print and forgotten (except by me and maybe a few others), but luckily still on library shelves.

Green Gables

It was not until 1985, when the mini-series adaptation of the book was aired on television, that Montgomery (LMM) came back into favor. Her books were re-issued, and eventually I was able to buy and read many of her novels. Once social media was accessible, we “kindred spirits” found each other. Many were my Jane Austen Society friends. One of the delights of finding my “kindred spirits” was doing group reads led by Sarah Emsley. The Blue Castle has become my favorite LMM book. Somehow I had never read it before the group read.

I love to travel and one of the trips on my list was a pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island. My husband, Jerry, surprised me by planning and executing the entire trip in September, 2005. I was finally able to walk on the paths that LMM had walked on, see rooms that she inhabited and really get a feel for the towns and scenery that she had experienced.

Nili at Green Gables

“Avonlea Village,” Cavendish, PEI

Anne of Green Gables Museum, Park Corner, PEI

Railway Station, Kensington, PEI

L.M. Montgomery’s Birthplace Museum, New London, PEI

I have tried to carry on the tradition that my mom began, by reading Anne with my kids, then with my grandkids. By reading it out loud together, we were able to experience the book cuddled up in bed. As many times as I read the book out loud with them, I could not get past Matthew’s death without crying. I would hand over the book to the child being read to, so that they could finish that chapter. I also shared my love of Anne with nieces, nephews, and friends. I lost count of how many “Anne” books I bought over the years. In addition, I shared my love of The Blue Castle with my daughter, Maggie, and my granddaughter, Kaitlyn. I am happy to say that they love it as much as I do.

Thank you to my “kindred spirit” friends, for allowing me to enjoy LMM with a group.

Nili Olay is a retired finance executive, who ended her career at RJR Nabisco as an Assistant Treasurer. Nili has a BA from the University of Chicago in Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations and an MBA in Accounting from Rutgers University, Newark, NJ. She also taught pre-school for a number of years between her undergraduate studies and her MBA.

Nili’s favourite authors are Jane Austen and L.M. Montgomery. She joined the Jane Austen Society of North America in 1985 and has held various positions such as National Board Member and Treasurer, as well as Regional Coordinator and AGM Coordinator.

When not reading Austen or Montgomery (or other beloved authors like D.E. Stevenson), Nili can often be found providing pro-bono financial advice to non-profits, travelling, practising her harp or piano or socializing with friends. Since retirement, Nili has travelled to out-of-the-way countries like Bhutan or Vietnam. She has been to eighty-seven countries and has combined her love of writing and travelling by publishing travel features and trip reports in International Travel News magazine. Nili tells me she is delighted to contribute her experience of reading L.M. Montgomery to the blog series.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “L. M. Montgomery and Emily Carr, Worshippers of the Woods,” is by Marianne Ward.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

L.M. Montgomery’s Poem “The Gable Window,” by Hughena Matheson

Anne Lives On, by Naomi MacKinnon

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Nili Olay 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 13, 2024

L.M. Montgomery’s Poem “The Gable Window,” by Hughena Matheson

“Prince Edward Island . . . is really a beautiful Province—the most beautiful place in America,” L.M. Montgomery wrote in her autobiography The Alpine Path. Islanders and visitors will no doubt agree with Montgomery, who had a special window onto the Island’s beauty.

She often looked out at the Island landscape from the upstairs gable window in the Cavendish home where she lived with the Macneills, her maternal grandparents.

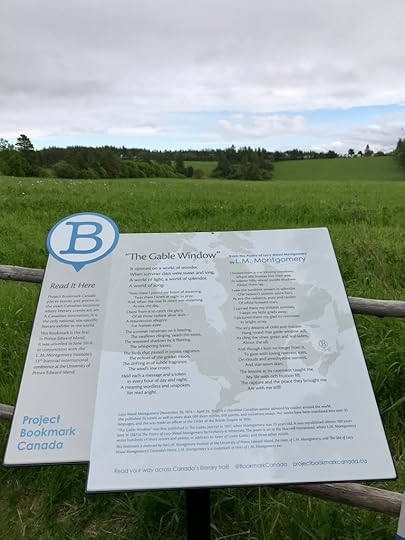

“The Gable Window,” by L.M. Montgomery, reproduced on a Project Bookmark Canada plaque at the Macneill Homestead, Cavendish, PEI

(From Sarah: This is the sixth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

A few years ago, my husband and I made a trip to Prince Edward Island. Besides the usual tourist attractions, I wanted to visit that very spot, the Macneill Homestead, now a National Historic Site.

I remember the day we arrived at the homestead. It was just after the busy tourist season, and we had the whole area to ourselves. What a peaceful day! We could wander the area without crowds of other tourists.

I was excited to visit the plaque inscribed with Montgomery’s poem “The Gable Window.” I am a member of the Board of Project Bookmark Canada, the small organization that is creating a literary trail across Canada. This unique trail is marked with plaques (Bookmarks) with a poem or passage from fiction installed in the exact location the writers imagined when writing the words.

As I was reading “The Gable Window” in the very place Montgomery imagined when writing her poem, I looked at the scene in front of me. I felt I was back when the writer lived there. An Islander had told me that apparently, the scene had not changed much over the years.

The poem describes the view as it was in 1897 when twenty-three-year-old Montgomery had her poem published in The Ladies Journal. “It opened on a world of wonder,” she writes, “When summer days were sweet and long, / A world of light, a world of splendor, / A world of song.”

Dr. Elizabeth Epperly, a Montgomery scholar and founder of UPEI’s L.M. Montgomery Institute, had suggested “The Gable Window” poem to Project Bookmark. Why this poem? Epperly writes: “There are so many lush and beautiful passages describing the Macneill place in the Anne and indeed Emily books. And right there is where the Montgomery fan experiences that ‘I know this place’ feeling and a sense of awe. The poem describes the exact fields outside her window.”

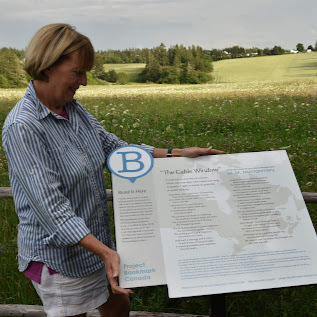

Dr. Elizabeth Epperly, speaking at the unveiling of the L.M. Montgomery Bookmark, June 24, 2018

Kate Macdonald Butler, President of the Heirs of L.M. Montgomery (Inc.), was very supportive of the Cavendish Bookmark: “The Heirs of L.M. Montgomery are delighted that the first official Bookmark on Prince Edward Island will honour L.M. Montgomery, and be on the Macneill site in Cavendish she loved so much—where she wrote hundreds of short stories and poems in addition to Anne of Green Gables and three other novels.”

I read the poem a few times and, just like Anne Shirley, Montgomery’s famous fictional redheaded Islander, who loves poetry that “gives you a crinkly feeling up and down your back” (Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 5), I got a “crinkly feeling” up and down my back.

Hughena Matheson was born and raised in Sydney, Cape Breton. She received a B.A. from Mount Allison University and then studied at the Ontario College of Education. For many years, Hughena taught English and Peer Tutoring in Ontario high schools. She was presented with a Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence (Certificate of Achievement) for 2001 – 2002, mainly for her work with Peer Tutoring. After retirement, Hughena worked for Rubicon Publishing, writing and editing for their series The 10. She also worked for Vitalink Canada Inc., marketing and selling educational materials to schools across Canada.

Hughena has served on the Board of Directors of Project Bookmark for many years, now in the position of president. She has written several articles about Bookmark for numerous newspapers across Canada. Also, she frequently writes opinion pieces for The Hamilton Spectator. She sent me this photo, taken when she and her husband visited the L.M. Montgomery Bookmark:

I (Sarah) took the photos of the L.M. Montgomery Bookmark, the unveiling ceremony, and lupines that appear earlier in this blog post. Since 2014, I’ve been volunteering with Project Bookmark Canada; you can read more about our Nova Scotia Reading Circle for Project Bookmark in this article Hughena wrote in 2017 for the organization’s newsletter. We meet at The Old Triangle pub in downtown Halifax, which we chose because it’s in the building where Montgomery worked as a journalist for the Daily Echo when she lived here from 1901 to 1902. Our group is currently working toward a Bookmark for Budge Wilson, author of several books, including a brilliant prequel to Anne of Green Gables entitled Before Green Gables.

Here’s a photo of Hughena and me in Toronto at the Bookmark for Ken Babstock’s poem “Essentialist” (taken by my daughter in the summer of 2023):

And here’s one more picture I took in PEI on the day the Montgomery Bookmark was unveiled:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “Discovering Anne of Green Gables in Tel-Aviv,” is by Nili Olay.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

Anne Lives On, by Naomi MacKinnon

People Who Love Our Places, by Logan Steiner

![Blue sky and green trees at Cavendish Grove, PEI; “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1730366883i/36120813._SX540_.jpg)

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Hughena Matheson 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 12, 2024

Anne Lives On, by Naomi MacKinnon

Prince Edward Island has been a part of my life since I was young; growing up in Nova Scotia made it an easy vacation destination. (Although I’m sure it didn’t always feel easy to my parents, who had to drive for nine hours with six children in the back of the vehicle.) We had camping friends whom we met on the Island when we could.

Between the two families, there were ten children and we liked to think the campground belonged to us alone. In those days, we camped at Stanhope campground, which was much less busy than Cavendish area, and one thing the grown-ups all seemed to agree on was that “tourist traps” were to be avoided. When we thought of PEI, we thought of Stanhope, the red sand beach across the road, the warm squishy tar filling the cracks in the road that we’d squeeze our toes into as we crossed, the wild raspberry bushes, games of hide-and-seek in the dark, and sunburns (at least, I think of the sunburns).

Stanhope Beach, 1981. That’s me at the back with the long white hair. My friend is sitting in front of me, to the right.

(From Sarah: This is the fifth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

Stanhope had a private campground—with cottages—up the hill behind ours that had its own little camping store. It had matches and hats, flip-flops and candy. But it also had a single, rotating book stand that—in my memory—held all of L.M. Montgomery’s books. In truth, it probably also held romances and mysteries, but I don’t remember those. My friend and I would climb the narrow path up the steep hill that was hidden in the bushes and stunted trees, and we would slowly spin that book stand, discussing which books we already had and which ones we still needed to get. My mother would let me pick one out each summer; sometimes—if I was really lucky—I might even get two.

L.M. Montgomery and her books felt magical to me. I had no idea how big she really was in the world. For all I cared, my friend and I were her only readers; she was all ours. We considered ourselves “kindred spirits.” We read the books together and—when apart—wrote letters to each other detailing what we’d read and what chapter we were on. When we moved on to the later books in the series, I felt secretly proud that my mother had six children just like Anne, and I spent hours (there was no internet back then) thinking up names for the children I was going to have some day, vowing to name them all after characters in Montgomery’s novels. (Needless to say, that didn’t happen. I do not have a daughter named Anne Cordelia. But my husband’s name is Matthew!)

My own kids in front of Green Gables, Summer 2010

It’s only natural that other Anne-lovers who have grown to become children’s authors would want to share their own love of the daydreaming, word-loving, magical character that is Anne, and the world of everything that is L.M. Montgomery, with young readers. Now that it’s in the public domain, they can, they have, and they do.

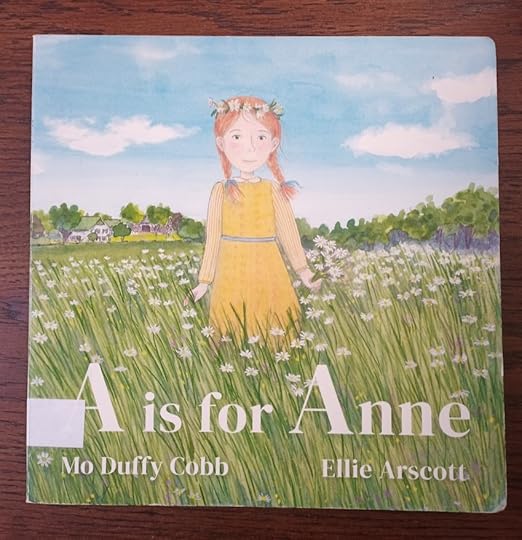

A is for Anne by Mo Duffy Cobb and Ellie Arscott is a lovely alphabetical introduction to Anne for young children. The succession of lyrics and illustrations follows the general storyline of Anne of Green Gables. The illustrations evoke the “Anne feeling” and general sense of the story, which an adult can feel free to elaborate on as their child grows. And I love that the illustrations include a more diverse group of children in Avonlea than the original story has, allowing children to imagine a better-represented version of the good folks of Avonlea.

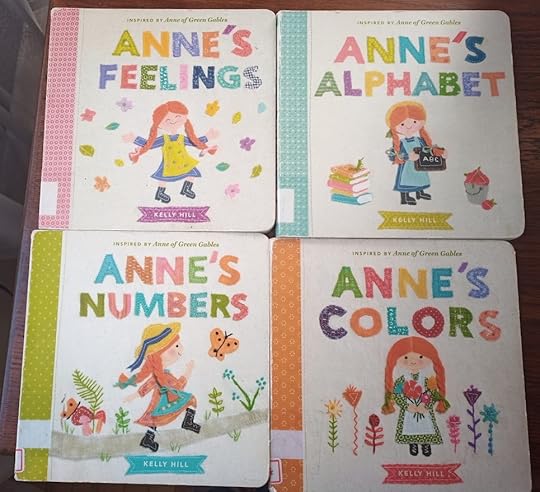

Also for young children is a set of four board books by Kelly Hill that cover basic concepts: letters, numbers, colours, and feelings. The illustrations are sweet quilted and embroidered depictions of Anne doing some of the things she does best: walking a rooftop, jumping on poor Aunt Josephine, wearing puffed sleeves, climbing trees, daydreaming, pouring raspberry cordial for Diana, and going home to Matthew and Marilla at Green Gables. In Anne’s Feelings, my favourite of the four books, Anne lies face down on her bed in the “depths of despair,” “Anne is angry” as she lifts a slate up over her head, “Anne is scared” as she walks through the haunted wood with Diana, and “Anne is surprised” when her hair turns green. Delightful!

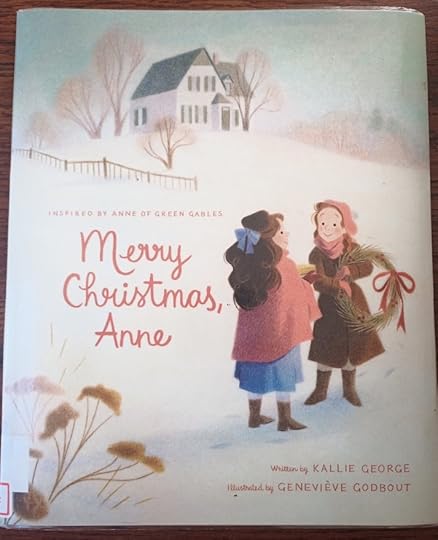

Moving on from basic concepts, author Kallie George and illustrator Genevieve Godbout have published picture books for children that include more words to accompany the illustrations. Rather than trying to tell the whole story in a picture book, George has chosen a focus for each book. If I Couldn’t Be Anne focuses on Anne’s excellent imagination, each page illustrating what she would like to be if she couldn’t be herself, while very much keeping Anne’s sentiments and personality. She might like to be the wind “dancing around the treetops,” “a lily maid, drifting dreamily through the summer,” or perhaps “an invisible friend who lives in a book.”

In Goodnight Anne, Anne does not want to go to sleep until she’s said goodnight to everyone she loves, including the Snow Queen and the Lake of Shining Waters. And, of course, Christmas in Avonlea is a very special time, and different from what children experience today. In Merry Christmas Anne, Anne puts on her new dress with the puffed sleeves as she gets ready to recite her poem at the Christmas concert. She uses words like “elegant” and “splendid” and is thankful for the “kindred spirits” who aren’t as “scarce” as she once thought.

Children will not need to wait until they are old enough to read the original novel to dream about sleeping in a wild cherry tree or to thrill over the names of the White Way of Delight and the Lake of Shining Waters with these books in their lives.

School-aged children can learn about Anne in small chunks as they read beginner chapter books written by Kallie George and illustrated by Abigail Halpin. Anne Arrives tells the familiar story of Anne coming to Green Gables by accident, including her outburst at Mrs. Lynde when she’s criticized about her looks. Much of the text is taken from the original, just condensed with a colourful illustration on each page.

Anne’s Kindred Spirits tells the tragic story of the brooch and the Sunday School picnic. And I’m sure you can guess which story is told in Anne’s Tragical Tea Party. Finally, Anne’s School Days includes the famous story of Anne breaking the slate over Gilbert’s head after he calls her “Carrots,” as well as his humiliating rescue of her from the river after she had been playing the lily maid.

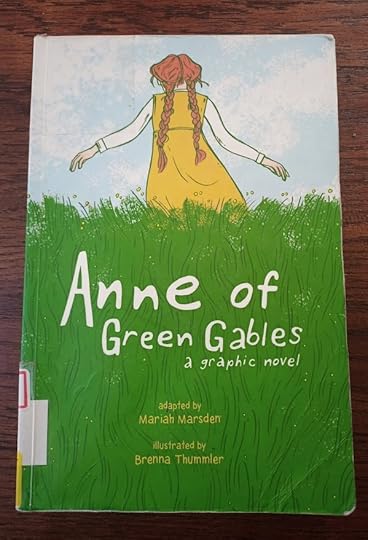

With the arrival of Anne of Green Gables: a graphic novel adapted by Mariah Marsden and illustrated by Brenna Thummler, reluctant readers no longer need to be left out of the pleasure of Anne’s story. Between the words and the illustrations, it covers all the bases of the original. Instead of the descriptive passages, there are beautiful illustrations to give readers that special Prince Edward Island feel.

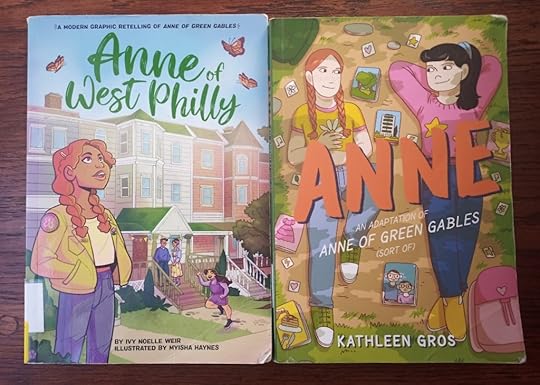

The biggest treat for me was reading the two graphic novel adaptations of Anne of Green Gables. I was unexpectedly taken by them; I enjoyed comparing them with the original story as well as with each other, and I loved discovering their unique perceptions of the characters.

Anne: an adaptation of Anne of Green Gables (sort of) by Kathleen Gros features a contemporary Anne who goes to live with Matthew and Marilla at the Avon-lea apartment building as a foster child. Matthew is the handyman at the Avon-lea and Marilla is an accountant: a very stylish one. Anne’s various adventures are given a modern makeover, but some incidents remain remarkably the same.

Anne of West Philly by Ivy Noelle Weir and illustrated by Myisha Haynes is also a contemporary Anne makeover. I was surprised by the similarities between the two graphic novels, both published in 2022. Again, Anne is a foster child being taken in by Matthew and Marilla, although she’s a year or two older in this version. In both versions, Anne and Gilbert are assigned by their teacher to work together on a big project, which leads to their reconciliation.

In both of the adapted graphic novels, Anne’s love interest is someone other than Gilbert. Part of me is pleasantly surprised and excited about this, but the other part of me—the nostalgic part of me—is sad to see them remain no more than friends and wonders where Gilbert will end up without Anne.

You can see by the illustrations that these graphic novels are ethnically and aesthetically different from one another. But, in both, the spirit of the story remains. Anne is smart and energetic with a lot to say; she has big emotions and a big heart. She remains a kindred spirit.

As a progressive herself, I like to think that L.M. Montgomery would approve of these updated versions of her book as they not only treasure the spirit of friendship, but carry on the spirit of progress as well.

Me and my daughters on the beach in Cavendish, 2022

Naomi MacKinnon lives in Nova Scotia with her husband, three kids, a dog, three cats, and a bunny. She works in the children’s department at the beautiful Truro Public Library, where she reads all the picture books and plays with the puppets. She blogs about books (mostly Canadian) at Consumed by Ink.

Over the past several years, Naomi and I have co-hosted online discussions of L.M. Montgomery’s novels, including The Blue Castle, Jane of Lantern Hill, The Story Girl and The Golden Road, and Kilmeny of the Orchard. If you’re interested in reading what we and other participants wrote about these books, you can find out more on my L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia page.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “L.M. Montgomery’s Poem ‘The Gable Window,’” is by Hughena Matheson.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

People Who Love Our Places, by Logan Steiner

The Making of a Story Girl, by Kerry Clare

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Naomi MacKinnon 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 8, 2024

People Who Love Our Places, by Logan Steiner

One trait I share with L.M. Montgomery (who went by Maud), the creator of some of my favorite books, is a love of place so deep that we are always using dressed-up adjectives to try to capture the feeling of them. Places can give us an immediate sense of peace and a far-out perspective. They can show us who we were before, and who we are now.

Prince Edward Island

(From Sarah: This is the fourth guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

We place lovers tend to vacation like robins, returning to the same nest each year. Maud’s dearest place, Prince Edward Island, has become one of my places. I visited when I began researching After Anne, my historical novel based on Maud’s life, and again in the summer of 2023 when the book came out. My mom, two-year-old daughter, and I visited for a third time less than a year later for a three-generations trip I will never forget.

Much has been written about the beauty of the Island and Maud’s books that made it famous. The combination of the two draws flocks of tourists year after year. But being pulled yet again from my home in Colorado to a faraway Canadian destination got me thinking not only about what makes the Island so compelling, but about the kind of people who find it so. What is it about people who love our places?

As I thought about this question, a well-known passage written by Maud late in her life stopped me in my tracks; it contains so much of the answer I was after:

You never know what peace is until you walk on the shores or in the fields or along the winding red roads of Prince Edward Island in a summer twilight when the dew is falling and the old stars are peeping out and the sea keeps its mighty tryst with the little land it loves. You find your soul then. You realize that youth is not a vanished thing but something that dwells forever in the heart. (The Spirit of Canada: Dominion and Provinces, 1939)

Love of place is first about the immediate feeling we have while being there—or better yet, walking there. Maud describes a felt sense of “peace” on Island walks. The Island likewise makes me feel settled inside. My family has its roots in two small Iowa farm-towns, and the Island has a familiar quality. It’s not just the kind of feeling, but the dependability of the feeling, that draws us place-lovers back to the same spots.

Then, too, we return to places that that help us experience, as Maud put it, “the flash” of the “enchanting realm beyond” (Emily of New Moon, Chapter 1). We see the “old stars” peep out, and the sea starts to take on its own character and relationship with the “the little land it loves.” I am always looking for experiences that help me not only remember in my head but feel in my body how old and large the universe is, putting my troubles in perspective. At least for me, these experiences often come when I’m not overwhelmed by new sights and sounds and scents. Not only nature but familiar nature helps me appreciate things like the age of the stars.

And then of course, revisiting places is also a way of revisiting our younger selves. “You find your soul then,” Maud writes, and “realize that youth is not a vanished thing.” This is a gift of returning to an old haunt that we can’t get by visiting a new one. We are never quite the same people we were the last time we visited. Returning to a dear place after a year away is a bit like catching up with a dear friend after a year apart:

It holds up a mirror—reflecting our past selves. A setting can return our youth to us or show us that it never really leaves us. I never spin around in innertubes like I do when we revisit my favorite Iowa lake in the summer.

Returning is also a marker—of how no place or person ever stays exactly the same. Maud’s relationship with the Island became more complicated later in life. She no longer lived there, and her favorite spots turned into tourist destinations. Her visits became both nourishing and heart-wrenching. Revisiting can reveal how our “youth” has become buried or our “soul” has become frayed. Even still, in showing us what we’ve lost and hope to find again, returning to the places we love is a gift.

Quotations are from The Spirit of Canada: Dominion and Provinces, 1939: a souvenir of welcome to H.M. King George VI and H.M. Queen Elizabeth (1939), an essay by L. M. Montgomery; and the Project Gutenberg edition of Emily of New Moon (2020). Photos contributed by Logan.

Logan Steiner is the award-winning and USA Today bestselling author of After Anne (HarperCollins 2023), which tells the story of Lucy Maud Montgomery. Logan also writes a weekly Substack newsletter called The Creative Sort. Her writing has appeared in Lit Hub, Writer’s Digest, Parents Magazine, 5280 Magazine, Nerd Daily, Electric Lit, and Women Writers, Women Books.

After graduating from Pomona College and Harvard Law School, Logan clerked for three federal judges, spent six years in Big Law, and served for three years as an Assistant United States Attorney. She now specializes in brief writing at a boutique law firm. Logan lives in Denver with her husband, daughter, and the cranky old man of the house, a Russian Blue cat named Taggart.

Logan’s essay “What Memory Keeps: Telling the Story of L.M. Montgomery’s Life” was published last month in the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “Anne Lives On,” is by Naomi MacKinnon.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them.

The Making of a Story Girl, by Kerry Clare

L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits, by Mary Beth Cavert

![Blue sky and green trees at Cavendish Grove, PEI; “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1730366883i/36120813._SX540_.jpg)

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Logan Steiner 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 6, 2024

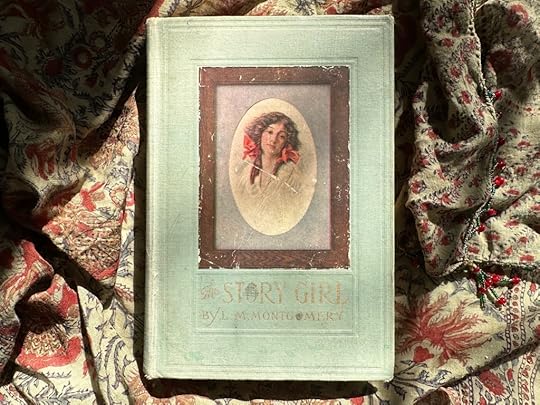

The Making of a Story Girl, by Kerry Clare

The first Anne of Green Gables I ever read was a story in the back of a colouring book I’d never put my crayons to, Anne in a few hundred words, an abridgement whose bigger picture still resonated, I assume, because I must have recently seen the movie. This was Kevin Sullivan’s 1985 production, which debuted on CBC TV when I was six, though I actually have no recollection of a time when I hadn’t seen it. And I’m sure I never used that colouring book—beyond the fact that I didn’t like colouring books in general, too little scope for the imagination—because the Anne in its drawings wasn’t Megan Follows, as the Anne of my imagination forever would be.

(From Sarah: This is the third guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!)

The abridgement, however, would go on to make me famous, however locally. Breaking Montgomery’s novel down to a nutshell, compact enough for me to hold this tale of a feisty orphan in my hand. I wanted to be Anne, and so I decided her abridged tale would be the text on which I based my entry in my school’s storytelling contest, a contest whose prize was a recording of my performance on video cassette, and I was indeed among the winners so immortalized. My story’s climax, I recall, was particularly dramatic, when Anne breaks her slate over Gilbert’s head after he dares to call her “Carrots,” and as a child with a penchant for attention, this entire experience would prove most formative. The works of Montgomery, for me, would always be entwined with both the act and the power of storytelling, as well as a licence to use my voice, to own it.

L.M. Montgomery made me a story girl. Throughout so many of her novels, the characters showed me what being a writer entailed, the practical matters, beyond the mere precociousness of declaring oneself as such (though I did that too). It wasn’t simply that Anne and Emily were themselves writers to the marrow, bursting with romantic ideas and florid vocabularies, but that they were unabashed in pursuit of this vocation. In Emily of New Moon, Emily is devoted to practicing writing vivid descriptions in her “Jimmy-books,” which were blank notebooks provided by her supportive cousin. Anne and her friends begin a Story Club in Anne of Avonlea, writing and sharing their own creative works, a conscious act of “cultivating” their imaginations. And I was always fascinated with (and envious of!) the cousins in The Golden Road who manage to create their own household newspaper, full of tales, tips, and teasing, inside jokes and local gossip, and spent my childhood coming up with inferior imitations. Through these different narratives, Montgomery demonstrates not only that a writer is someone who writes, but also how this is done and how storytelling can connect us to each other and the wider community.

![A page from “The Kid Town Times”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1731076679i/36145679._SY540_.jpg)

In Montgomery’s novels, storytelling is an act of self-preservation, from Anne Shirley’s romantic fantasies during those desperate early years before her arrival at Green Gables to the otherworldly tales Valancy Stirling weaves for herself to survive her years of drudgery and disdain until she’s finally able to escape the clutches of her terrible family.

Stories are also the stitches that hold Montgomery’s imagined worlds together, including the family lore and oral histories conveyed in books like The Blue Castle, A Tangled Web and others. Sometimes these stories are in the background, adding that essential texture that seems to bring fiction to life, and other times they’re the stuff of plot itself—think of the rumours about Barney Snaith in The Blue Castle that compel Valancy to cast off society in The Blue Castle and turn her life into a gothic romance, or Leslie Moore in Anne’s House of Dreams whose own sad story provides her a “tragic air” until a twist of fate (via some cutting-edge neurosurgery) comes along and changes everything.

Anne learns about what happened to Leslie Moore from a most prolific storyteller, Miss Cornelia Bryant, a figure who complicates negative connotations of the local busybody, as she delivers Leslie’s story with kindness and sympathy, though the reader senses that she still revels in the telling: “Well, I may as well begin at the beginning and tell you everything straight through, so you’ll understand it” (Chapter 11).

Stories, sometimes, are just another word for “gossip,” and gossip itself is at the heart of much of Montgomery’s fiction, often delivered, notably, by her most memorable characters. Though there are indeed essential moments when her prolific gossips receive a necessary comeuppance. Note when Rachel Lynde finally meets Anne—newly arrived at Green Gables—and unleashes a torrent of judgement about Anne’s appearance, Anne gives back to her as good as she gets, a beautiful kind of justice, and even Marilla (almost) agrees, in a line at the end of the scene I would have likely glossed over as a young reader (because I think one needs to be older to appreciate the delicate lines with which Marilla’s character is sketched): “She was as angry with herself as with Anne, because, whenever she recalled Mrs. Rachel’s dumbfounded countenance her lips twitched with amusement and she felt a most reprehensible desire to laugh” (Chapter 9).

It’s not the act of gossiping that’s the problem, but instead the judgement that might underline it, for which Valancy Stirling calls out her small-minded relatives:

“Can’t you leave poor Cissy Gay alone? She’s dying. Whatever she did, God or the Devil has punished her enough for it. You needn’t take a hand, too. As for Barney Snaith, the only crime he has been guilty of is living to himself and minding his own business. He can, it seems, get along without you. Which is an unpardonable sin, of course, in your little snobocracy.” (Chapter 11)

But it’s not for nothing, I think, that Mrs. Rachel Lynde is the beginning of everything, her very name the opening words of Montgomery’s very first book, and the world begins to be built from her point of view, most literally:

. . . for not even a brook could run past Mrs. Rachel Lynde’s door without due regard for decency and decorum; it probably was conscious that Mrs. Rachel was sitting at her window, keeping a sharp eye on everything that passed, from brooks and children up, and that if she noticed anything odd or out of place, she would never rest until she had ferreted out the whys and wherefores thereof. (Chapter 1)

Rachel Lynde’s kind of discovery is not necessarily malicious, instead sometimes the result of a desire to really understand the world and its workings. This is not the stuff of gossip, instead this is data. Marina Endicott calls it this in her 2023 novel The Observer, when she has her protagonist explain, “But I needed more information, more data—not for gossip, but to understand [her partner’s] situation and my own, to understand and choose how to live my own life.” I think of the gendered element with which gossip is maligned, how the creators of a “Shitty Men in Media” google doc in 2017 (naming alleged perpetrators of sexual assault and sexual harassment) were held to account in ways that shitty men so rarely are—and now I’m thinking of Miss Cornelia again, for reasons that will be clear to anybody who recalls her signature catchphrase.

Rachel Lynde was possibly as much an influence on me as Montgomery’s other more dreamy creations were, showing me that it was also possible to be fierce, and principled, and sometimes wrong, and—even more important—willing to admit to being wrong. Mrs. Rachel was a story girl just as much as Emily Byrd Starr, and just as I don’t think Anne would have been Anne without her, neither would I be the unabashedly gossipy (data-driven!) storyteller I am today.

Kerry Clare is the author of three novels, Asking for a Friend, Waiting for a Star to Fall and Mitzi Bytes, and editor of The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood. A National Magazine Award-nominated essayist, and editor of Canadian books website 49thShelf.com, she is host of the BOOKSPO podcast and writes about books and reading at her longtime blog, Pickle Me This. She lives in Toronto with her family.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.” The next post, “People Who Love Our Places,” is by Logan Steiner.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits, by Mary Beth Cavert

Welcome to “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150”

![Blue sky and green trees at Cavendish Grove, PEI; “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150”]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1730366883i/36120813._SX540_.jpg)

Read more about my books, including St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

Guest post copyright Kerry Clare 2024; additional text copyright Sarah Emsley 2024 ~ All rights reserved. No AI training: material on http://www.sarahemsley.com may not be used to “train” generative AI technologies.

November 4, 2024

L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits, by Mary Beth Cavert

It is an honour to participate in another wonderful tribute event to celebrate the 150 years since L.M. Montgomery’s birth. She made a “safe landing on the shores of time” (Rilla of Ingleside, Chapter 28) in a small village in Canada, on a cold and wet late November day in 1874, but her life stories and legacy have flourished in breadth and depth ever since. Her books have never been out of print.

(From Sarah: This is the second guest post in “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” which began on October 30th and will continue through to Montgomery’s birthday, November 30th. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about LMM in the comments here and on social media: #LMM150. Thanks for celebrating Montgomery’s birthday with us!

The title of the series comes from Montgomery’s description of what Emily Starr calls “the flash” in Emily of New Moon:

It had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside—but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond—only a glimpse—and heard a note of unearthly music. . . . And always when the flash came to her Emily felt that life was a wonderful, mysterious thing of persistent beauty.)

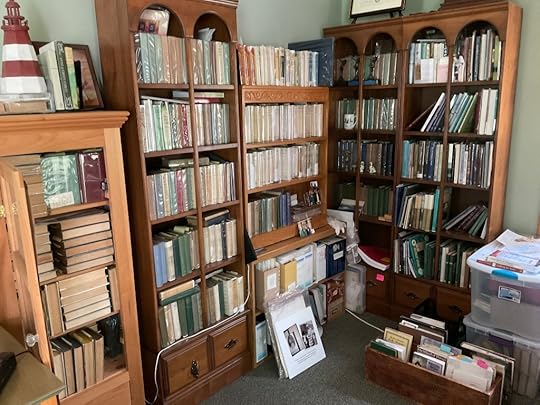

My mother was a fan of Montgomery; as a child in the 1920s and 30s, she would wait at the train stop in her rural town of fifty people to receive the library book basket so she could get whatever Montgomery book was in it first. However, I never knew this until I entered the Montgomery world on my own after my red-haired daughter was born. It was then that I read all the Montgomery books in paperback and then started to collect first, early, and unique editions. I have had as many as seven hundred on the shelves and find that many of my favourites are ones with inscriptions. The messages share happy times from the past: Jack loved Claudia when he gave her Rainbow Valley, Betty’s mom and dad gave her Anne of Avonlea for Christmas in 1909, Stella got The Golden Road for her birthday in 1925 from Grandma in England, the Malvern Hotel in Bar Harbor, Maine, kept a July 1908 Anne of Green Gables on hand for its guests, Anne’s House of Dreams was awarded to Irene for good grades.

My daughter and I went on a tour of Montgomery sites on PEI in 1992. I visited Maud’s Ontario sites in 1993 (Bala, Norval, Leaskdale, the archives at Guelph University); then I attended the first L.M. Montgomery Institute Conference at the University of Prince Edward Island in 1994. I was hooked. I enjoyed every aspect of Montgomery’s stories immensely and Montgomery’s journals engaged me even more.

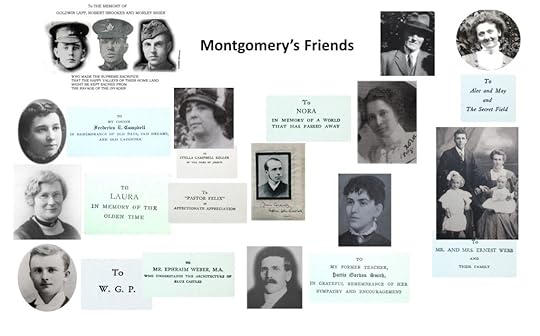

One of reasons that countless readers enjoy and return again and again to L.M. Montgomery’s stories is to wrap themselves up in the relationships and friendship she created in them. Friendship was the door that I chose to enter the imagination of L.M. Montgomery, sparked by the statement of a scholar in 1994 at the Montgomery Conference: “[Montgomery’s] writings are a record of her desire for the kind of friends she craved” (from Mary H. Rubio’s Harvesting Thistles). This statement sparked a question that I wanted to pursue—to explore her friendships, were they absent or full-formed? My key was to use all of her book dedications to examine significant people in her life. And, indeed, I found that Montgomery had many authentic relationships and that she didn’t crave for friends, but craved their presence and mourned their absences.

In 1994 I started to supplement the information in Montgomery’s published letters and the irregular threads about her friends in her journals by contacting the family members of those friends to find letters, hear recollections, and see family artifacts. I also examined numerous, and sometimes conflicting, historical records to support or amend oral histories. There was not the wealth of digital information as there is today. I dug up obituaries and looked up names in telephone books. Then I wrote letters to likely names in those telephone directories. Sometimes I got letters back immediately, and sometimes not until ten years later after a parent died and relatives went through their papers! And, as always, the best help was from librarians!

As a result of that research, I was able to reveal the previously unknown life stories of some of her friends at the 1996 Montgomery Institute Conference, which initiated several deeply treasured friendships and collaborations with Elizabeth Waterston, Mary Rubio, and Elizabeth Epperly in Canada, as well as many others world-wide. Afterwards, I was gratified to see that overlooked details that I found, like poet John McCrae‘s presence at Montgomery’s meeting with Lord Earl Grey, had been well-received and that there had been re-evaluations of the importance of her year living in Prince Albert and her friendships with the Pritchard and MacGregor Families. Her relatives have become close to my heart, especially her cousins, Frede, Stella, Bertie, Tillie, and Myrtle. My most surprising early discoveries were the lives of Nora Lefurgey and Hattie Gordon—two accomplished and remarkable people! It has been a wonderful experience to locate some of the dedication families and share with them the importance of their great-grandparent to this famous author.

About ten years ago I was asked to edit the entire collection of Montgomery’s letters to her dear friend in Scotland, George B. MacMillan. (You can find my MacMillan presentation, in my Covid voice, here: About L.M. Montgomery: Mary Beth Cavert: L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits: The One in Scotland. Hosted by Daniela Janes, Caroline E. Jones, Benjamin Lefebvre, Andrea McKenzie.)

George B. MacMillan

It took a great deal of time and collaboration with my own dear friends to get it ready for a publisher. As happens with all of Maud’s friends, I became very fond of George. The process of research never ends and never fails to surprise. After I finished the whole MacMillan project in 2020, entirely new treasure-troves of their correspondence were uncovered in 2021 and 2024—just in time to slip them into the manuscript!

Now I am working hard to finish the manuscript I started in 1995, L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits. It will be the story of every one of her book dedications. It is a kind of biography collection, about all the people with whom she formed unbroken bonds early in her life, before she became famous. For me, the stories behind the dedications not only reveal Montgomery’s tight circle of friends, but also illuminate happy aspects of her life that are sometimes overlooked. This long-brewing project has also enhanced my personal life. Maud has given me the gift of friends from all over the world who continue to enrich my spirits far beyond any borders or generations.