Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 10

July 5, 2024

Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility, by Deb Barnum

“Come, come, let’s have no secrets among friends.”

(Volume 2, Chapter 4)

Mrs. Jennings may request “no secrets among friends,” and Marianne may “abhor all concealment” (Volume 1, Chapter 11), but Sense and Sensibility is chock full of both—many secrets, much concealed—within each character, between characters, and between the author and the reader.

(From Sarah: This is the sixth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

P.D. James, in her essay “Emma Considered as a Detective Story,” defines the detective story as one “requiring a mystery, facts which are hidden from the reader but which he or she should be able to discover by logical deduction from clues inserted in the novel with deceptive cunning but essential fairness. It is about evaluating evidence . . . it is concerned with bringing order out of disorder and restoring peace and tranquility to a world temporarily disrupted by the intrusions of alien influences.”

Such is Emma, truly a mystery, where Jane Austen gives us clues and puzzles and hints along the way, whereby we the reader can solve the underlying mystery right along with Mr. Knightley, who gets awfully close, but not quite close enough, to the solution.

But Sense and Sensibility offers no such clues to assist either the novel’s characters or the reader to any understanding of what is happening. Patricia Meyer Spacks writes: “Gradually the novel reveals that almost everyone has a secret, everyone—even characters dedicated to morality—conceals something” (“Afterword,” Sense and Sensibility [1982]). Thorell Tsomondo says: “. . . these secrets contribute to the query and puzzlement that characterizes the work” (“Imperfect Articulation: A Saving Instability in Sense and Sensibility” [Persuasions 12 (1990)]). Emma may be a mystery, but in S&S, it is all confusion, the reader not in on it. We are led to believe that Elinor is all-seeing, but indeed she often misunderstands, is wrong in her assumptions. We are presented with a Willoughby described, his true self a secret to all, as a good person, the perfect Romantic Hero (though we should have heeded the warning: “his person and air were equal to what her fancy had ever drawn for the hero of a favourite story” [Volume 1, Chapter 9])—and here Austen conceals perhaps the biggest secret of all, that it is her Colonel Brandon who is the true Romantic Hero of S&S, flannel waistcoat and all.

“Carried her down the hill,” C. E. Brock, S&S (courtesy of Molland’s)

Tuning into the myriad of secrets in S&S is certainly not new ground: a number of scholars have written about the issue of pervading secrecy in this novel (see references below). So these thoughts are nothing new, but I found it helpful to look at the extent of the secrecy. Indeed, the words “secret,” “secrecy,” “conceal,” “deceive,” “betray,” all appear numerous times in S&S. And more telling perhaps is the occurrence of “silent” or “silence,” certainly another aspect of secrecy—the decision not to tell, not to speak, to remain silent rather than reveal. Another word count to note is “eyes”—Austen often referring to what the eyes see when words are deceptive or untruthful, or when silence is chosen and characters rely on “the eyes” to perceive the truth: recall Elinor’s frequent reference to Lucy’s “little sharp eyes,” and Mrs. Dashwood, upon learning that her favorite Willoughby is really such a cad, remarks that “there was always a something in [his] eyes at times, which I did not like” (Volume 3, Chapter 9).

There is in S&S also an element of surprise—surprise being a secret of sorts—in the unexpected arrivals of the various heroes: Marianne declares almost verbatim on two occasions “It is he . . . I know it is!” expecting Willoughby and facing the disappointing “surprise” of Colonel Brandon and later Edward. Elinor is awaiting her mother and the Colonel and is surprised (as we all are—this feels like a Brontë novel!) when “she rushed forwards and . . . saw only Willoughby” (Volume 3, Chapter 7). (This gives short shift to a topic that needs an essay all its own!)

Secrets, of course, are a form of manipulation—and there is much of this going on as well. The story begins with a secret—on his deathbed, Henry Dashwood requests his son to help his second wife and three daughters. (Indeed the whole change in the inheritance from his Uncle to the young Dashwood boy was a secret revealed at the will-reading.) Mr. John Dashwood thought to offer a present of £1000 a-piece to each of his sisters and Mrs. Dashwood is led to believe he will take care of them in some way, “[relying] on the liberality of his intentions” (Volume 1, Chapter 3)—alas! to no avail, as Fanny Dashwood assiduously talks him out of doing anything in one of the most cringe-inducing chapters in all of literature. So the novel begins—with concealment and deception.

All three of the male characters in S&S harbor the secret of a previous romantic entanglement, what Paula Byrne calls “a parody of secret engagements” (Jane Austen and the Theatre [2002]). Edward’s secret engagement to Lucy; and Willoughby’s seduction and abandonment of Colonel Brandon’s ward Eliza. The reader is misled about these characters—we believe as Mrs. Dashwood and Elinor and Marianne do, that the unexpected departures (that element of surprise again) of both Edward and Willoughby are due to the expressed displeasure of their respective parent-figure, Mrs. Ferrars for Edward, Mrs. Smith for Willoughby.

“Col. Brandon was invited to visit her” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1898 (my collection)

Colonel Brandon is, of course, a walking secret—with his past of “injuries and disappointments” (Volume 1, Chapter 10), the story of his first love hinted at throughout—“I once knew a lady” (Volume 1, Chapter 11) is only (and secretly) revealed to Elinor and the reader in Chapter 9 of Volume 2 as he explains his secret past, his secret-laden departure to London, his secretive dual with Willoughby, “the meeting never [getting] abroad.”

Even the ridiculous Robert Ferrars has a secret—his deceptive growing relationship with Lucy, his remaining hidden in the rear of the carriage when he and Lucy meet up with Thomas. Why, Robert Ferrars’ entire character IS a secret—we are introduced to him as the fop in the jewelry store long before we find out who he is. What a surprise Austen has in store for us when she makes him the plot-solver! And dare we forget Mr. Palmer?, a Scrooge-like character, who surprises us all when his secret is revealed that he is actually not such a bad fellow after all.

“Introduced him to her as Mr Robert Ferrars” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1908 (courtesy of GoogleBooks)

But it is not just the men who have secrets, the women do as well—all of them. Lucy’s engagement, her “great secret” and her use of this to manipulate Elinor is what drives the plot. But Elinor is the keeper of secrets—she tells no one about Lucy’s engagement, keeping to her promise; she keeps Brandon’s secrets; but she also conceals her own feelings about Edward, she “mourns in secret” when she believes she has lost him forever, and she keeps secrets from herself—she remains “assured within herself of being really beloved by Edward” (Volume 2, Chapter 1), when we from the text have no such certainty. And for two sisters so close, she and Marianne keep their most important thoughts and feelings from each other. Elinor speaks of “this strange kind of secrecy maintained by them relative to their engagement” (Volume 1, Chapter 14); she cannot, nor will Mrs. Dashwood, break into their “extraordinary silence” (Volume 1, Chapter 14) to discover the truth. Months go by in this state of non-communication. Marianne’s oft-quoted “we have neither of us any thing to tell; you, because you communicate, and I, because I conceal nothing” (Volume 2, Chapter 5) is sure proof that nothing is as it seems inside the strange world of Sense and Sensibility. Marianne’s claim is the ultimate irony, when, indeed, Elinor has been completely silent on her own inner turmoil, and Marianne, though unable to control her emotions, has been concealing everything. “Ask nothing,” she says to Elinor, “you shall soon know all” (Volume 2, Chapter 7).

La Belle Assemblee, 1807

Society at the time required circumspect behaviors, especially of its female members—one acted demurely, maintained secrets, told polite lies. As Tony Tanner says, “. . . it was a society that forced people to be at once very sociable and very private” (Jane Austen [1986]). Byrne talks of the “the level of deceit in the marriage market” (Jane Austen and the Theatre [2002]), and Spacks goes so far as to say that the entire “plot of S&S suggests that women must and men should conceal their feelings” (“Afterword,” Sense and Sensibility [1982]). When Elinor admonishes Marianne “Pray, pray be composed and do not betray what you feel to every body present” (Volume 2, Chapter 6) as Marianne screams for Willoughby to attend her, we are seeing this conflict of honest expression versus proper behavior. In the beginning of the novel, there are several references to Elinor needing to tell little lies, “the whole task of telling lies when politeness requires it” (Volume 1, Chapter 21), unlike Marianne, who wears everything on her sleeve. Elinor later in the novel becomes less able to perform these social niceties—she more and more responds with silence, this repeated numerous times, with the final wordless bolting from the room upon hearing that Edward is free of Lucy.

“His errand . . . was a simple one. It was only to ask Elinor to marry him” C.E. Brock, S&S (my collection)

One forgets in tearing S&S down to its bare bones, what with all these secrets; all the duplicitous characters lurking about; the lies (can we ever really forgive Edward for his secrecy and the outright lie about the ring?); all the behind the scenes seriousness of Colonel Brandon’s history of lost love, his secret duel (we must add here Brandon’s very quick reference to his ward Eliza’s friend, “who with a most obstinate and ill-judged secrecy [my italics] would tell nothing, would give no clue, though she certainly knew it all” [Volume 2, Chapter 9] regarding Eliza’s whereabouts); and Willoughby’s betrayal of both Eliza and Marianne—with all this, how easy it is to forget that S&S is a comedy after all! Is there anything more laugh-inducing that the scene when Edward arrives to find both his Lucy and his Elinor together?—I know that you know but pretending I don’t know, etc.—a perfectly drawn piece of theater (for an insightful look at Austen’s love of and use of such dramatic elements, see Byrne).

And who better to return us to good humor that Mrs. Jennings, certainly the most loveable and endearing of Austen’s cast of annoying characters. If in Elinor we have the keeper of secrets, in Mrs. Jennings we have the lover and teller of secrets, the good-natured gossip, though she most often gets it all wrong. She (along with Sir John Middleton) makes much of the secret letter “F”; she is sure that Colonel Brandon has a “natural daughter”; tells all that Marianne and Willoughby are secretly engaged; gossips that Willoughby and Miss Gray are to be married; and ends with “the important secret in her possession” (Volume 3, Chapter 4) that Elinor and the Colonel are to be engaged! Mrs. Jennings certainly personifies Austen’s belief in gossip as a living social entity that undermines the keeping of secrets: in her letter to Cassandra of 5 September 1796:

Mr. Richard Harvey is going to be married; but as it is a great secret, & only known to half the Neighborhood, you must not mention it. The Lady’s name is Musgrove.

‘With a letter in her outstretched hand” – C. E. Brock, S&S, Dent, 1898 (Internet Archive)

But let’s return to the concept of Jane Austen as the writer of detective stories. Margaret Ann Doody in her introduction to the Oxford edition of S&S quotes Joseph Wiesenfarth: “the very structure of the novel attempts to engage and develop the total personalities of Elinor and Marianne by presenting them with a series of mysteries that must be solved.” Doody says that “the characters are all detectives trying to put together this piece and that piece of information.” She cites Mrs. Jennings’ declaration to Marianne: “I have found you out in spite of all your tricks” about the latter’s secret visit to Allenham with Willoughby, showing that all the characters are in a sense spying on each other to get at the truth (“Introduction,” Sense and Sensibility [2008]).

An abundance of secrets will certainly set any detective worth her/his salt to action—and Sense and Sensibility does not disappoint, despite an inherent sense of confusion. And so all ends as all good English novels do—with the requisite comedic ending, where the truth will out, all is revealed, each character is given their just due, and whether you like that Marianne ends up with Colonel Brandon or not (another essay!), and we are told that Willoughby will forever regard Marianne as “his secret standard of perfection in woman” (Volume 3, Chapter 14), order is restored, and all is quite right with the world.

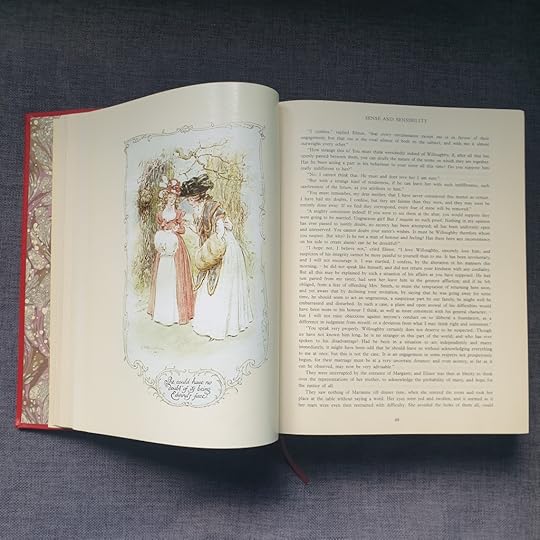

The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. by R. W. Chapman. 3rd. ed. Oxford, 1933, 1988 printing (my collection)

Quotations are from the 3rd Oxford edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited by R. W. Chapman, 1988 printing; and the 4th Oxford edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (2011, 2014 pb ed.). This essay is a slightly edited version of a post for Maria Grazia’s blog tour of Sense and Sensibility on June 19, 2011 at “My Jane Austen Book Club,” and reposted with her permission.

I welcome your comments! Can you remember the first time you read Sense and Sensibility? What secret in the novel most surprised you?

“Elinor agreed to it all, for she did not think he deserved the compliment of rational opposition.”

Further Reading:

Byrne, Paula. Jane Austen and the Theatre. London: Hambledon, 2002.

Doody, Margaret Ann. “Introduction.” Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2008.

Drabble, Margaret, “Introduction.” 1989. Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New York: Signet, 1997.

James, P. D. “Emma Considered as a Detective Story.” Time to Be in Earnest: A Fragment of Autobiography. New York: Knopf, 2000.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. “Afterword.” Sense and Sensibility. By Jane Austen. New York: Bantam, 1982.

Tanner, Tony. Jane Austen. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1986.

Tsomondo, Thorell. “Imperfect Articulation: A Saving Instability in Sense and Sensibility.” Persuasions 12 (1990): 90-110.

Wiesenfarth, Joseph. “The Mysteries of Sense and Sensibility.” The Errand of Form: An Assay of Jane Austen’s Art. New York: Fordham UP, 1967.

Deb Barnum, author of the Jane Austen in Vermont website, had a former career as a law librarian and later owner of a used bookshop. She is a lifetime member of JASNA, co-founded the JASNA-Vermont Region, now helps the JASNA-South Carolina Region; gives various talks on Jane Austen and other writers at the OLLI program at USCB; is a board member of the North American Friends of Chawton House; and assists with locating the Lost Sheep of Godmersham Park for Peter Sabor’s “Reading with Austen” project and writes its corresponding blog at https://readingwithaustenblog.com/ . She took the photo of irises in Spain at the Alhambra.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “At Home with Sense and Sensibility,” is by Lizzie Dunford, and I’ve scheduled it for Sunday, July 7th, because that’s the anniversary of the date Jane moved to Chawton Cottage in 1809, along with her sister Cassandra, their mother, and their friend Martha Lloyd.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, by S.K. Rizzolo

The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility, by Deborah Yaffe

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

July 2, 2024

Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, by S.K. Rizzolo

According to Ellen R. Belton, “the pattern of mystery is a vitalizing structural principle in all of Austen’s novels” (“Mystery Without Murder: The Detective Plots of Jane Austen” [Nineteenth-Century Literature 43.1 [1988]). Sense and Sensibility fits this pattern as Elinor Dashwood acts as a kind of detective, striving to penetrate the secrets that threaten her own happiness and that of her beloved sister Marianne. Secrets, in fact, are the lifeblood of mystery stories—and any secret possesses a dangerously unpredictable power. To protect herself, Elinor remains guarded until it’s safe to show her vulnerability. In the meantime, she uses her “sensing” apparatus—that is, her rational intelligence and keen powers of observation, paired with earnest efforts to restrain her impulses—to steer a course through murky, shark-infested social waters.

(From Sarah: This is the fifth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Let there be no mistake—the consequences of failure are very real. Austen may not give us a dead body on the library carpet—but, as shown by the fate of the two Elizas (one is Colonel Brandon’s tragic first love; the other, her daughter seduced by Willoughby), any woman who fatally misreads a lover’s character can expect disgrace and suffering. Marianne, who scorns to hide her feelings, pays a high price for bestowing her affection on the charismatic Willoughby too soon. Indeed, she nearly dies of grief. Elinor, more cautious, humbly acknowledges the risk of error in herself and others: “I have frequently detected myself in such kind of mistakes . . . in a total misapprehension of character in some point or other. . . . Sometimes one is guided by what [people] say of themselves, and very frequently by what other people say of them, without giving oneself time to deliberate and judge” (Volume 1, Chapter 17). As a result, she waits until the mysteries surrounding her lover, Edward Ferrars, are exposed before she confesses her love.

Of course, no mystery novel is complete without the clues, which theoretically point to an objective truth. In a mystery novel, this might be a bloodstained glove, a handkerchief dropped at a murder scene, or a discrepancy in an alibi. Austen does something similar in her novel as Elinor struggles to read the tangible signs she encounters in order to gain a better understanding of the people around her. Though not infallible, she is usually more right than wrong, probably because she waits to commit herself until she has more information. The clues are important, but in Austen, they tend to evoke complicated assessments of human nature, rather than pat solutions.

Let’s look at two of these clues—the dual locks of hair or love tokens. The first belongs to Marianne, and its origin is clear because Elinor’s younger sister Margaret witnesses the moment when Marianne gives it to Willoughby. Later this lock of hair seems to be proof positive of Willoughby’s unmitigated villainy when he encloses it in the insolent letter sent to Marianne ending their relationship. But, as it turns out, this clue is not so straightforward, as Elinor herself realizes when a distracted Willoughby shows up to confess his love for the gravely ill Marianne. The cruelty expressed in the letter was not Willoughby’s, after all. Every word of it, as well as the decision to return the lock of hair, comes from Willoughby’s jealous fiancée. None of which excuses Willoughby, as Elinor comments to her sister: “The whole of his behaviour . . . from the beginning to the end of the affair, has been grounded on selfishness” (Volume 3, Chapter 11). Intentional cruelty toward a woman he had genuine feelings for? No. Pursuit of his own pleasures and mercenary interests at Marianne’s expense? Yes.

Willoughby cuts off a lock of Marianne’s hair while she gazes at him adoringly. Illustration by Hugh Thomson (1860-1920).

What about the second love token? Elinor spots a lock of dark hair in a ring worn by Edward Ferrars and immediately feels “satisfied” the hair is her own (Volume 1, Chapter 18). And on what slender grounds! (For one thing, it’s hard to imagine the staid Edward creeping up behind Elinor with the scissors. . . .) But the hair is the same shade as hers, and she is convinced that despite his reticence, Edward reciprocates her feelings. Jumping to conclusions is an unusual lapse for Elinor, a kind of wishful thinking she usually avoids, and I think it stems from the strength of her regard for him. However, when presented with irrefutable proof she’s made a mistake, Elinor doesn’t shrink from reality. The hair is Lucy Steele’s and is concrete evidence of the engagement between her and Edward. Even then Elinor keeps her composure and resigns herself to losing her lover, although she experiences “an emotion and distress beyond any thing she had ever felt before” (Volume 1, Chapter 22). Still, this clue isn’t very straightforward either. It doesn’t prove Edward’s love for Lucy. Instead it’s indicative of his youthful folly in entangling himself in an unwise engagement and then being too honorable to abandon his promise. Elinor ultimately reaches a solid understanding of his character—with Austen’s wry commentary infused in the narrative voice: “His heart was now open to Elinor, all its weaknesses, all its errors confessed, and his first boyish attachment to Lucy treated with all the philosophic dignity of twenty-four” (Volume 3, Chapter 13). Edward, though flawed like the rest of us, can finally take his rightful place as her partner.

My favorite clue—or perhaps it’s better referred to as a red herring—is Colonel Brandon’s flannel waistcoat. No lover worth his salt would ever wear such a garment, and it suggests that Brandon, all of thirty-five, is an ailing dotard with one foot in the grave. Thus, in Marianne’s eyes, he can never become a figure of romance. Once again, looks are deceptive. Brandon is pure, steady, upright—he embodies a veritable catalog of virtues. And he harbors a poetic soul, falling in love with Marianne at first sight and nobly dedicating himself to her service. Austen has fun joking about the dashing of Marianne’s absurd romantic pretentions but also gives her the requisite happy ending: “Marianne could never love by halves; and her whole heart became, in time, as much devoted to her husband, as it had once been to Willoughby” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

By the end of the novel, the secrets have been dispelled, and the hearts of the characters are open to each other. But in Austen’s scheme that doesn’t mean that all the wicked people are cast into hell, while the virtuous are elevated to an implausible sainthood (even Willoughby goes on to enjoy a reasonably contented life.) Austen is after something richer and more complicated than a simple moral equation. As Elinor and Marianne’s cold, greedy brother says in a moment of unintended irony: “Well, I am convinced that there is a vast deal of inconsistency in almost every human character” (Volume 3, Chapter 5). Very true—but Elinor’s patient observation has been amply rewarded. In the fullness of time and with her admirable sleuthing skills, she has arrived at a just estimation of the truth.

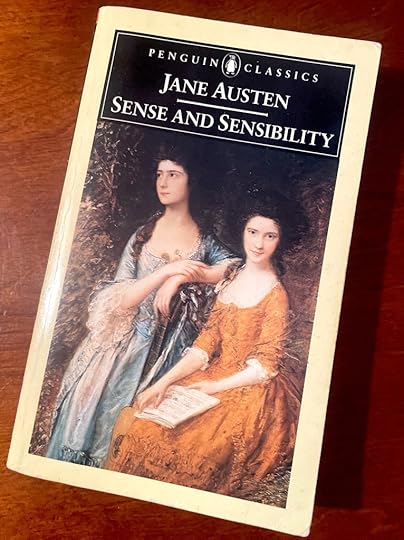

Quotations are from the Penguin Classics edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited with an introduction and notes by Ros Ballaster (2014).

S.K. Rizzolo earned an M.A. in literature before becoming a high school English teacher and author. A lifelong Anglophile and history enthusiast, she loves writing about the lives of women. Rizzolo got the writing bug when her only child was a little girl and went on to publish four Regency mysteries with the highly regarded Poisoned Pen Press. Her mysteries feature an unconventional lady, a Bow Street Runner, and a melancholic barrister. Rizzolo will soon launch a new Victorian series introducing a “redundant” spinster striving to become a young Miss Marple. The flower photos are from her garden in the San Fernando Valley in Southern California. https://skrizzolo.com/

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Secrets and Silence in Sense and Sensibility,” is by Deb Barnum.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility, by Deborah Yaffe

Sense and Sensibility in my most need, by Heidi LM Jacobs

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

June 28, 2024

The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility, by Deborah Yaffe

For a romantic comedy, Sense and Sensibility is a startlingly dark book. And that darkness inheres not solely in the novel’s disturbing plot elements—economic dispossession, familial cruelty, romantic betrayal—but perhaps especially in its brutally negative portrayal of social life: the social life available to its heroines and, by extension, to all of us.

Park Güell in Barcelona

(From Sarah: This is the fourth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Outside their family circle, and sometimes even within it, the Dashwood sisters’ social world is a place of disconnection and dissimulation. It’s a place where bonds are frequently superficial: The novel’s most compulsively sociable character, Sir John Middleton, can’t even tell the difference between physical proximity and emotional closeness—“to be together was, in his opinion, to be intimate” (Volume 1, Chapter 21). It’s a place where etiquette requires spending time with people you don’t like, and who don’t like you: In London, Elinor and Marianne reluctantly pass their days with Lady Middleton and the Steele sisters, “by whom their company, in fact was as little valued, as it was professedly sought” (Volume 2, Chapter 14). It’s a place where pain is inflicted routinely—either inadvertently, as with the relentless “letter F” (Volume 1, Chapter 21) jokes that torture Elinor; or deliberately, as with Lucy Steele’s passive-aggressive jabs. Above all, the social world of Sense and Sensibility is a place where concealment and artifice are mandatory, where participation requires that you master the “task of telling lies when politeness required it” (Volume 1, Chapter 21)—of thinking things you can’t say, and saying things you don’t believe.

All these characteristics of social life are on vivid display during John and Fanny Dashwood’s dinner party (Volume 2, Chapter 12), the most excruciating of the book’s long procession of dull, awkward, or hurtful social occasions.

The gathering is a study in disconnection: Almost no one fully understands the agendas and motivations of their fellow guests. Ignorant of the secret engagement, Mrs. Ferrars and Fanny patronize Lucy and slight Elinor; talking to Colonel Brandon, John Dashwood disparages the beauty of the sister Brandon loves while praising the artistry of the one he doesn’t. No one has anything substantive to say (“no poverty of any kind, except of conversation, appeared—but there, the deficiency was considerable”), and the verbal interactions pulse with a symbolic competitiveness. When the men are present, the topics of discussion are “politics, inclosing land, and breaking horses”—a nutshell summation of the ways in which Regency men exercise power (social, economic, physical) over others. When the women are alone, this male struggle for primacy in the public world is transmuted into a proxy war waged in the domestic sphere, as the mothers and grandmothers debate the relative height—literally, the status—of their male offspring. Sometimes, words are used with an intent to wound, as when Fanny Dashwood and her mother flatter the absent Miss Morton in order to disparage Elinor. But just as often, pain is inflicted involuntarily: Although meant to console her sister, Marianne’s conspicuously emotive response hurts more than the insults that provoked it.

Throughout the dinner party sequence, Austen deploys her characteristic free indirect discourse to heighten the atmosphere of emptiness and alienation. First, acerbic reflections in Austen’s narratorial voice—Mrs. Ferrars “was not a woman of many words; for, unlike people in general, she proportioned them to the number of her ideas”—turn her critique of particular characters into a broader indictment of “people in general.” And then Austen seamlessly slides into Elinor’s mind, allowing us to eavesdrop on the internal monologue that this expert painter of pretty screens is screening from public view. We listen in as Elinor considers, and then rejects, the temptation to meet Lucy’s baiting with a cutting reference to her romantic rival Miss Morton, instead assuring Lucy “with great sincerity, that she did pity her.” We hear Elinor register Mrs. Ferrars’ rudeness and then tell herself, perhaps self-deceivingly, that she is impervious to it (“a few months ago it would have hurt her exceedingly; but it was not in Mrs. Ferrars’ power to distress her by it now”). And we share in Elinor’s bitter amusement at the spectacle of Fanny and her mother patronizing the Steeles (“while she smiled at a graciousness so misapplied, she could not reflect on the mean-spirited folly from which it sprung, nor observe the studied attentions with which the Miss Steeles courted its continuance, without thoroughly despising them all four”). Outwardly, Elinor is calm, polite—even, apparently, sincere—as she enacts necessary social lies. Inwardly, she observes, and despises.

El Retiro Park in Madrid

What makes the dinner party sequence hilarious is the dual consciousness that Austen’s free indirect discourse grants us. Whether rendered as omniscient narrative or as internal monologue, this voice tells the truth about the shallowness, artificiality, and unkindness of the dinner guests, freeing us from the socially mandated lying that burdens the Dashwood sisters. We are granted a privilege that the characters don’t have—the license to laugh at this world without being trapped inside it. But precisely because this episode is so funny, it’s easy to overlook its brutality, and what that brutality implies about the stifling nature of the demands social life makes on the Dashwood sisters. Austen hints at that brutality when she characterizes Elinor’s response with a startlingly bleak word: “despising.” Elizabeth Bennet is amused by her social world, but Elinor Dashwood hates hers. What, we may wonder, is the cost of the concealment that social life requires of Elinor and Marianne—and perhaps of the rest of us, as well?

Austen grants us a brief, oblique insight into that cost a few chapters later, after the secret engagement has come to light. For once, Elinor has succeeded in forcing Marianne to adopt the socially mandated repression that she herself has practiced throughout the novel: Marianne has promised to speak politely of the Edward-Lucy match. Marianne “performed her promise of being discreet, to admiration,” we learn. “She listened to [Mrs. Jennings’] praise of Lucy with only moving from one chair to another, and when Mrs. Jennings talked of Edward’s affection, it cost her only a spasm in her throat” (Volume 3, Chapter 1).

“Only a spasm in her throat”: It’s hard to imagine a more viscerally powerful evocation of the painful—almost physically painful—price of keeping silent, of literally swallowing an authentic response. It’s a tiny moment that, by illuminating everything that’s come before it, brings the darkness of Sense and Sensibility into the light.

Quotations are from the e-text of Sense and Sensibility at Mollands.net, retrieved on 3 May 2024. Photos contributed by Deborah.

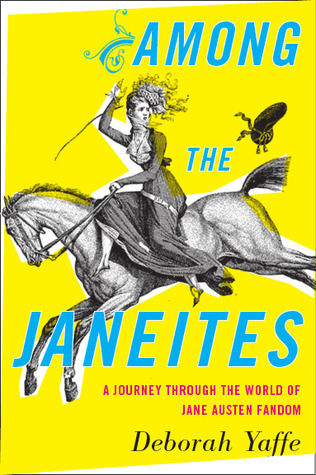

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance journalist and the author of Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom (Mariner Books, 2013). She blogs about Austen-related matters at https://www.deborahyaffe.com/.

Part of Deborah’s collection of Austen-related souvenirs

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Mysteries of the Human Heart in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility,” is by S.K. Rizzolo.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sense and Sensibility in my most need, by Heidi LM Jacobs

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

June 25, 2024

Sense and Sensibility in my most need, by Heidi LM Jacobs

At the risk of sounding too much like Marianne Dashwood, I feel compelled to admit I’m going through a rough patch. Still gutted from the loss of one parent several years ago, I’m confronting the mortality of the other and the inevitable letting go of the one home our family has lived in. I have seen countless friends and family members deal with this very thing. But having watched others navigate this difficult road doesn’t make it any less bewildering or any less real.

A late-night phone call from my brother and the hasty purchase of a one-way ticket to Edmonton in late April pushed this essay I’d promised to Sarah out of my head. By the time I looked at my planner last week, I realized the due date was hurtling toward me and the fear of missing this impending deadline sent me into a space of dread.

I dug out my prospectus and saw that I said I would write about how Sense and Sensibility was my gateway Jane Austen novel, purchased with a Christmas gift certificate from my Auntie Cathy at a Coles bookshop in Edmonton when I was the exact age of Marianne Dashwood. I am not sure why I selected Sense and Sensibility but this purchase changed my life’s course.

(From Sarah: This is the third guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I had been looking forward to writing this piece and had set aside the first two weeks of May for a leisurely reread of Sense and Sensibility and the following two weeks to craft my essay. I anticipated writing something lighthearted—maybe discussing my realizations that I’m now older than Mrs. Dashwood, whose existence as an interesting person was clearly over, or that the ancient, “infirm,” and flannel waistcoat-wearing Colonel Brandon was just on the wrong side of five and thirty. I also thought I might take my young self to task for remembering every detail of Willoughby’s carrying Marianne through the rain yet skimming over his reprehensible actions. For a time I thought Willoughby the best of all Jane Austen’s suitors because he read poetry and bought Marianne a horse.

Determined to meet my deadline, I picked up my original copy of Sense and Sensibility and sat at my desk with a pencil and notebook for several mornings in a row. Each morning, I quickly became distracted and put the book down to do other things. None of those early topics felt like what I wanted to write. I realize now that to read my original copy of Sense and Sensibility meant going back to being almost 17 and reading on the mid-century teak furniture still in my parents’ living room. I also read this book in my childhood bedroom that’s still filled with my books and those I gave my Mum over the years. In the foreseeable future, I know I will need to find new homes for all of the things that made our house home to us for so many years.

Unsurprisingly, more tears than words were generated at my desk. After the third morning of indulging my inner Marianne, I took on a decidedly more Elinor approach. I downloaded an audio book of Sense and Sensibility and went for a series of long walks. I was no longer reading the same pages as my young self, no longer smiling at what I’d underlined or starred: “It is not every one who has your passion for dead leaves” was a particular favourite (Volume 1, Chapter 16). By listening and simply letting the words fall over me as I walked through woods and neighbourhoods, along train tracks and the river, I was experiencing an entirely new novel.

In my first readings of this novel as a teenager, I saw only binaries: sense or sensibility, emotion or restraint, Willoughby or Colonel Brandon, Elinor or Marianne. I’d relied so much on my earlier ways of reading over the years that I’d never noticed that this book begins with the death of a parent and the loss of a home. I also saw for the first time that this is a novel about grief and heartbreak and about finding one’s path through life’s difficult parts. It’s not Sense vs Sensibility or Marianne vs Elinor. It’s Sense and Sensibility. It is Marianne and Elinor.

After listening to the audio book, I flipped through the notations in my original copy. I was surprised to see that my younger self had underlined a passage that brought me to a halt on my walk: “’Dear, dear Norland!’ said Marianne as she wandered alone on the last evening of being there. . . . And you, ye well-known trees!—but you will continue the same.—No leaf will decay because we are removed . . . you will continue the same: unconscious of the pleasure or the regret you occasion, and insensible of any change in those who walk under your shade” (Volume 1, Chapter 5). A younger me had written “trees” in the margin beside this underlined passage—maybe for a paper. But this version of me was stopped in my tracks by this passage because I couldn’t see the path for the tears in my eyes. I know that when we do finally sell our family house, I will stand in our backyard one last time and stare up at the towering elm trees that were saplings when I was born. They grew as I did and I used to climb and read under them all summer. I know I will remember this passage from my favourite novel and that I will cry. But I will also carry on. I will be both Marianne and Elinor, sense and sensibility.

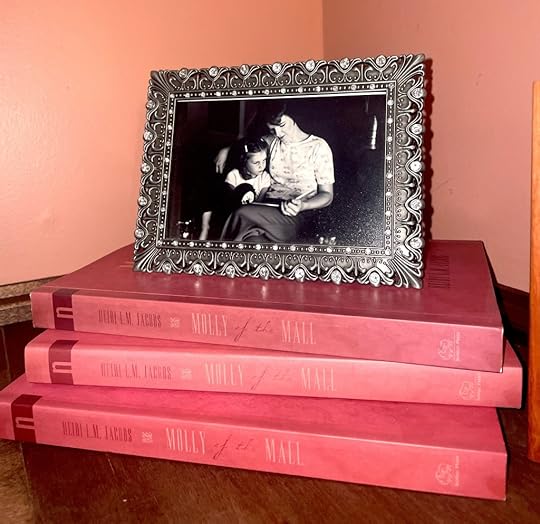

In Molly of the Mall, I wrote about how the ten-year-old Molly reads the publisher’s motto in her copy of Emma as a directive: “Everyman, I will go with thee, and be thy guide, / In thy most need to go by thy side.” When I wrote that, I ascribed those emotions to a fictional character. I have long known that the Christmas gift certificate got me the book that would go with me and be my guide for my lifetime. What I did not know until this week is that Sense and Sensibility would also be the novel that in my most need, would go by my side.

Quotations are from the Penguin edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Tony Tanner (1969, 1986). All photos by Heidi.

Heidi LM Jacobs is a librarian at the University of Windsor and the author of three books including the Leacock award winning Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass and Purveyor of Fine Footwear (NeWest Press, 2019).

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “The Darkness of Sense and Sensibility,” is by Deborah Yaffe.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

June 21, 2024

What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes, by Finola Austin

Over the years, whenever I’ve read or re-read Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (published 1811), or watched various stage and movie adaptations, I’ve wondered what my own verdict should be—sense or sensibility? Or, in other words, Elinor or Marianne?

As an older sister myself, I have a natural bias towards Elinor, and Austen certainly wants us to see her as the true heroine of her novel. After all, our first introduction to Marianne, written with typical Austenian litotes, is, “Marianne’s abilities were, in many respects, quite equal to Elinor’s” (Volume 1, Chapter 1), which leverages understatement to draw our attention to the younger sister’s relative failings. However, there is much I found, and still find, appealing about Marianne’s romantic, artistic, and, yes, at times overly dramatic disposition.

(From Sarah: This is the second guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began yesterday and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Elinor and Marianne was Austen’s original title for the novel. So central is this contrasting pair to the book and its themes that many fans forget about the existence of the other Dashwood sister—Margaret. But recently I found myself flicking through the book with a new eye, doing a “Margaret read” to understand if there were any details about the third sister I might have overlooked.

It wasn’t a promising start. There are over 120K words in Sense and Sensibility, yet Margaret’s name is mentioned a mere 36 times.

Austen gives us this pretty damning introduction to her character, which comes just after Marianne’s: “Margaret, the other sister, was a good-humored, well-disposed girl; but as she had already imbibed a good deal of Marianne’s romance, without having much of her sense, she did not, at thirteen, bid fair to equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). In the real world, someone saying you probably won’t live up to your older siblings can probably be shrugged off. But when an omniscient Austenian narrator says this, you’re in for trouble.

Poor Margaret! She’s proven wrong pretty much whenever she expresses an opinion throughout the novel. She dismisses Colonel Brandon for being “on the wrong side of five and thirty” (Volume 1, Chapter 7). She’s convinced Marianne and Willoughby will marry. And she sets off optimistically with Marianne on their ill-fated walk, which leads to Marianne’s fall in the rain.

Margaret may only be thirteen, but that doesn’t mean she’s spared harsh critiques for her silliness. Austen tells us Margaret refers to Willoughby as “Marianne’s preserver . . . with more elegance than precision” (Volume 1, Chapter 10). And—here comes that litotes again!—when Margaret puts her foot in her mouth speaking about Elinor and Edward, we get this particularly withering line: “Margaret’s sagacity was not always displayed in a way so satisfactory to her sister” (Volume 1, Chapter 12).

But, slight as the character work on Margaret is, Austen doesn’t veer into caricature when writing about her. The good humor and disposition Austen mentions upfront comes through at certain moments, like in this interaction, which underlines Margaret’s lack of material worldliness and contrasts her with Marianne to Margaret’s advantage:

“I wish,” said Margaret, striking out a novel thought, “that somebody would give us all a large fortune apiece!”

“Oh that they would!” cried Marianne, her eyes sparkling with animation, and her cheeks glowing with the delight of such imaginary happiness.

“We are all unanimous in that wish, I suppose,” said Elinor, “in spite of the insufficiency of wealth.”

“Oh dear!” cried Margaret, “how happy I should be! I wonder what I should do with it!”

Marianne looked as if she had no doubt on that point.

(Volume 1, Chapter 17)

Near the end of the novel too Margaret demonstrates loyalty and sensitivity toward Elinor, after her previous carelessness about her feelings: “Margaret, understanding some part, but not the whole of the case, thought it incumbent on her to be dignified, and therefore took a seat as far from [Edward] as she could, and maintained a strict silence” (Volume 3, Chapter 12).

The references to Margaret’s limitations are still there (she still doesn’t fully understand what is going on), but this change from her earlier indiscretion when talking about Elinor’s emotions gives us a glimmer of hope that she may yet learn from her older sisters’ (and particularly Elinor’s) example.

The last reference we have to Margaret in the novel teases us further about who she might be when she’s grown: “fortunately for Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, when Marianne was taken from them, Margaret had reached an age highly suitable for dancing, and not very ineligible for being supposed to have a lover” (Volume 3, Chapter 14). For now, Margaret’s prospects are merely a diversion for her neighbors. But in a few short years, could she too be in for her own romantic adventure?

Overall, on this read, I was struck most by the believability of Margaret. She might not be crucial to the premise of Sense and Sensibility, like Elinor or Marianne, and at times she is used as a device to move the story forward (as in the hair cutting scene with Willoughby). Yet, of all three sisters, Margaret seems most like a girl we’ve probably all met—flawed and socially inexperienced, but, above all, relatable.

Quotations are from the Project Gutenberg edition of Sense and Sensibility. The wild rose photos were taken earlier this week in Greenwich, Prince Edward Island (by Sarah).

Finola Austin is an England-born, Northern-Ireland-raised, Brooklyn-based author of historical fiction. Her debut novel, Bronte’s Mistress , was published by Atria Books in 2020. She is the writer behind the Secret Victorianist , a blog on nineteenth-century literature and culture. By day, she works in digital advertising. Find her online at www.finolaaustin.com .

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Sense and Sensibility in my most need,” is by Heidi L.M. Jacobs.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

June 20, 2024

Sisters and Sisterhood, by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

The mid-1990s was a good time to discover the works of Jane Austen. Having grown up in different towns in the north of England, we each have strong memories of settling down on the sofa on Sunday evenings to watch the famous BBC TV series of Pride and Prejudice, and of trips to our local cinemas where we experienced Ang Lee’s visually sumptuous Sense and Sensibility. And who can forget Clueless, written and directed by Amy Heckerling, which loosely transposed the plot of Emma to that of a Beverly Hills high school—familiar to us in terms of the nineties era, if not the social milieu? Enjoyable as these adaptations were, their most important effect was that they encouraged us to turn to Austen’s original words.

(From Sarah: This is the first guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

We each recall chatting about our reading with our younger sisters—conversations that seem particularly fitting since Austen was so close to her own sister, Cassandra. Austen enjoyed the benefits of sororal closeness in a more figurative sense, too, through her friendships with Martha Lloyd, for instance, and the amateur playwright and governess, Anne Sharp. We explored the latter’s connection with the celebrated author in our cowritten group biography about female literary friendship, A Secret Sisterhood.

Given Austen’s close bonds with other women, it’s unsurprising that the subjects of sisters and sisterliness frequently recur as themes in her novels. On rereading Sense and Sensibility recently, we were struck anew by the extent to which its plot turns on the inner workings of the relationships of two sets of sisters: the likable Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, and their antitheses Anne and Lucy Steele.

These pairs of siblings are on such opposing sides of the reader’s sympathies that it is easy to miss the similarities in the way each of these relationships functions. The two older Dashwood sisters are famously presented as opposites in temperament. We are told in the first chapter that Elinor “possessed a strength of understanding, and coolness of judgement,” whereas the younger Marianne was “eager in every thing; her sorrows, her joys, could have no moderation” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). When, later, we meet the Miss Steeles we learn that the older Anne was endowed with “a very plain and not a sensible face,” whereas Lucy has “considerable beauty” and a manner of being that is more consciously refined than that of her sister (Volume 1, Chapter 21). Despite their outward differences, however, Lucy and Anne, and also Marianne and Elinor, can be regarded as sisters alike at heart.

The Complete Works of Jane Austen, The Illustrated Library, published by Midpoint Press, 2006. A gift to Emily from her sister, Erica.

In the Miss Dashwoods’ case, the two young women bridge the gap between them through their shared sense of honour, loyalty and love. As for Anne and Lucy, though the older sister is decidedly dull, whereas Lucy is quick-witted and regarded by many as amusing, their chief aims in life are much the same: the pursuit of “beaux” and their accompanying fortunes, and the gaining of favour with any person of influence. Although it is tempting to see the Dashwood sisters in a positive light while regarding the Miss Steeles as vulgar and mercenary, it is worth remembering that, given the limited opportunities for women of the era, there may have been some wisdom to the latter pair’s behaviour. Thought of that way, it’s possible to regard these sisters, too, with some compassion and understanding.

One admitted contrast between the Dashwoods and the Steeles is the extent to which each young woman within a pair attempts to change the other. Of the two Dashwoods, Elinor represents sense, Marianne sensibility. Through much of the novel each is so assured of the righteousness of her own stance that she is constantly trying to reform her sister. Lucy sometimes seems embarrassed by Anne’s comparatively coarse way of speaking and the carelessness of her manner, but she rarely does more than chiding her behaviour in the moment. Neither sister seems able to look at herself or her sibling with enough reflection to evaluate the aspects of their personalities that might be in need of reform. Indeed, this lack of insight on Anne’s part leads her to reveal the truth about her younger sister’s secret engagement to Edward Ferrars to his furious mother—an unintentionally harmful act that nearly results in the social ruin of both the Miss Steeles.

By the end of Sense and Sensibility, Elinor and Marianne have grown as characters. They have reached a better understanding of each other and have become less judgemental. By staying true to their principles they have been rewarded with matrimony—a state of romantic bliss which, Austen assures us, will do nothing to shake their own sisterly bond since the two still live “without disagreement,” very happily “within sight of each other” (Volume 3, Chapter 14).

Through clever manoeuvring, Lucy has also been rewarded with marriage, but her union with the vain and irresponsible Robert Ferrars cannot ever be the same kind of attachment as the true and genuine affection Elinor shares with his brother, or which Marianne is taken aback to find she can embrace with Colonel Brandon. As for Anne, the suggestion is surely that, at almost thirty when we first meet her, she is destined to remain a spinster. To be unmarried was rarely presented as enviable in literature of the period, interestingly not even by an author like Austen—someone who turned down a marriage proposal, thereby choosing to remain single, a status that allowed her to prioritise her writing. It isn’t clear whether, having so distressed the formidable Mrs. Ferrars, Anne can ever fully be taken into the fold of her sister’s new clan. Lucy has previously seemed loyal to Anne, but both of the Miss Steeles are essentially self-centred, so the extent to which she will try to help her older sibling is also similarly uncertain.

Sense and Sensibility is, of course, just as much a novel about sisters and sisterhood as it is about love and marriage—more so, even. In this, her first published novel, Austen celebrates the steadfast nature of Marianne and Elinor’s bond, which withstands outside crises and misunderstandings from within to become even stronger by the book’s end. Austen’s own sisterly relations with the women closest to her experienced their own occasional ructions, but her surviving letters illustrate that she attached great importance to these attachments. They sustained her through her life’s ups and downs, including the long period during which she laboured at her craft without any commercial success. Sense and Sensibility, for instance, begun in the mid-1790s, was not published until 1811.

Awareness of the various “sisters” who supported the unknown Austen has been of great importance to us through the years. At the time that we began researching A Secret Sisterhood, we had long been struggling as unpublished authors, and so—in this respect at least—we felt we had something in common with our literary heroine. We took heart in the knowledge that, after many years of unrecognised toil, Austen achieved publication, just as we hoped we would too in the end. And we consoled ourselves that, like Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, and Austen and her closest female influences, we would have our sisterly bond to keep us going until then.

Quotations are from the Norton Critical edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited and with an introduction by Claudia L. Johnson (2002). All photos contributed by Emily and Emma.

Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney are the co-authors of A Secret Sisterhood: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf, for which Margaret Atwood supplied the foreword. You can explore some of their earlier writing about female literary friendship at http://www.somethingrhymed.com. Emma is a lecturer in creative writing at the Open University and a director of the Ruppin Agency Writers’ Studio, as well as the author of the novel Owl Song at Dawn. Emily is a lecturer on the writing programme at NYU London and the author of Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice. Their websites are emilymidorikawa.com and emmaclairesweeney.com. You can also find Emma on X @emmacsweeney and on Facebook. You can find Emily on Instagram (and Threads) @midorikawaemily and on X as @emilymidorikawa.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “What About Margaret? Reading Sense and Sensibility with Fresh Eyes,” is by Finola Austin.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

“More than I can tell” (Quotations from Alice Munro)

June 14, 2024

Your invitation to A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility

Please join me for “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” a new series of guest posts, which will launch next Thursday with an essay on “Sisters and Sisterhood,” by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney.

With the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, this is a great time to celebrate her first published novel. We’ll begin on the first day of summer, June 20th, and the series will run through to the end of the season, with a couple of posts each week, usually on Tuesdays and Fridays.

“A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” will feature guest posts by Maggie Arnold, Finola Austin, Elaine Bander, Deb Barnum, Sandra Barry, Cheryl Bell, Matthew Berry, Diana Birchall, L. Bao Bui, Kathy Cawsey, Carol Chernega, Lori Mulligan Davis, Lizzie Dunford, Susan Allen Ford, Paul Gordon, Collins Hemingway, Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Natalie Jenner, Hazel Jones, George Justice, Theresa Kenney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Shawna Lemay, Emily Midorikawa, Jessica Richard, S.K. Rizzolo, Peter Sabor, Vic Sanborn, Marilyn Smulders, Jacqueline Stevens, Emma Claire Sweeney, Joyce Tarpley, Janet Todd, and Deborah Yaffe, along with two teenagers, Gail and Ria, who are reading S&S for the first time.

I’ve hosted blog series celebrations for Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, and I’m excited to read and celebrate Sense and Sensibility with all of you. Please share this invitation with anyone who might like to join us in discussing Austen’s first novel.

I’ll collect the links to all the posts in the series on this page, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.”

In the fall, I’ll be hosting a blog series celebrating the 150th anniversary of L.M. Montgomery’s birth. I hope you’ll join us for that one as well!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“More than I can tell” (Quotations from Alice Munro)

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?” (Photos from my trip to Oxford, Mississippi)

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

June 7, 2024

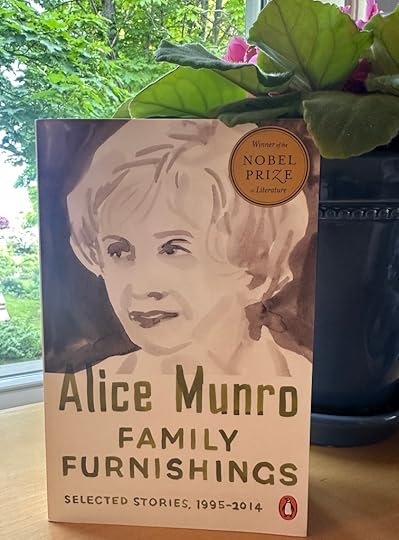

“More than I can tell”

My title comes from Alice Munro’s afterword to L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, in which she writes of the experience of reading the novel for the first time at age ten:

In this book, as in all the books I’ve loved, there’s so much going on behind, or beyond, the proper story. There’s life spreading out behind the story—the book’s life—and we see it out of the corner of the eye. The milk pails in the dairy-house. Aunt Elizabeth pouring the tallow for the candles. The slightly repulsive splendour of the parlour at Wyther Grange. The corners of the kitchen at New Moon. What mattered to me finally in this book, what was to matter most to me in books from then on, was knowing more about life than I’d been told, and more than I can tell.

(From the New Canadian Library edition of Emily of New Moon)

Munro quotes from another edition of Emily of New Moon, which claims on the cover that in this story the heroine discovers she is not alone, and she says she disagrees with this assessment of the novel. She objects to the “familiar brisk assumption” that books are supposed to “spread messages, and that the messages are cheery and confining.” She says she doesn’t know what book Montgomery intended to write, but the one she did write “is surely one in which Emily finds that she is alone, that she has chosen her life without knowing that she was choosing it, and she’s exultant about the choice.”

Like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, who famously says “I care for myself” (Jane Eyre, Chapter 27), Emily Starr announces proudly, “I am important to myself,” after she’s been told she is “not of much importance” (Chapter 3). I like Munro’s word “exultant.” I was sad to hear of her death last month, at the age of 92, and I’ve been revisiting some of her writing and favourite quotations from her work.

I like what she says about how “Writing fiction is seldom something that has to be done that day.” In a 2005 essay called “Writing. Or, Giving Up Writing,” Munro says, “in order to have time to do my work I must continually refuse to do things that other people think perfectly reasonable and even obligatory for me to do, and sometimes I get mad enough to tear out my hair.” As she reflects on her decision to give up writing, she asks what made writing “irresistible” in the first place.

She says it isn’t the work or sending the work out or seeing it published or reading it to an audience or seeing it on a bestseller list or seeing it win a prize. Instead, she asks, “Isn’t the really good time when you are just getting the idea, or rather when you encounter the idea, bump into it, as if it has always been wandering around in your head?” She says, “It’s not the story—it’s more like the spirit, the centre, of the story, something there’s no word for, that can only come into life, a public sort of life, when words are wrapped around it” (Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke).

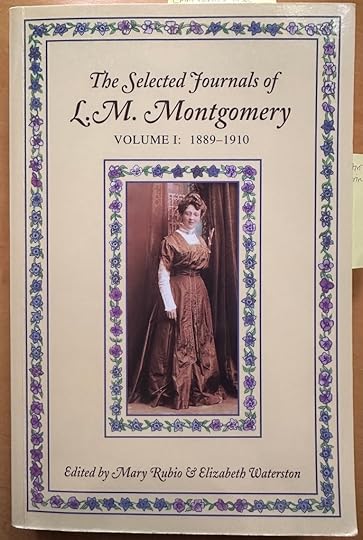

I’ve always liked Mary Henley Rubio’s story about the day she gave Munro a copy of the first volume of The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery in late 1985. Rubio says, “she looked at it for only a second to see what it was, and then, without missing a beat or without making any reference to Emily of New Moon, she responded by quoting the end of the novel: ‘I am going to write a diary that it may be published when I die’” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings).

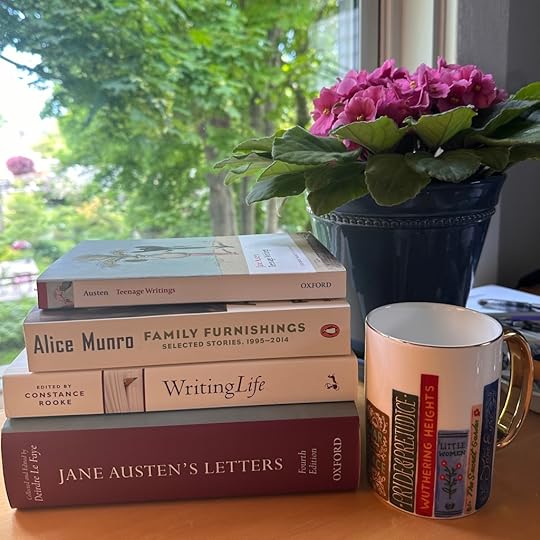

I’m in the middle of writing an essay for this year’s JASNA AGM in Cleveland, Ohio. It’s called “‘She placed her bonnet on his head & ran away’: Stealing Sources and Avoiding Consequences in Jane Austen’s Fiction,” and I’ve been turning to Munro for that as well. I’m intrigued by what the narrator says in her story “Family Furnishings” about how planning to write fiction is “more like grabbing something out of the air than constructing stories.” I’m also rereading essays by Margaret Drabble, Eudora Welty, and other writers, exploring Drabble’s claim that “The ‘writing life’ is a life of crime.” (Like the Munro essay I quoted above, Drabble’s essay also appears in Writing Life, edited by Constance Rooke.) I’m especially interested in Austen’s heroine “The Beautifull Cassandra,” who steals a bonnet from her mother’s shop and runs off to seek her adventures.

If I start writing in detail about either the Beautifull Cassandra or Alice Munro’s stories right now, this will turn into a very long post. I’m tempted! It would be an excellent way to procrastinate. If I spent more time on Munro’s stories, I’d start with “Nettles,” one of my favourites. But I want to go back to working on my JASNA lecture, and so I’ll just add a wonderful quotation about Munro’s work from The Philadelphia Inquirer, and then I’ll end with some photos sent to me by my friend Sandra Barry.

Munro was “A writer who slowly fashioned a house of fiction large enough for both a room of her own and all of her family furnishings—ensuring that she herself had space to maneuver while others still had plenty of space to stretch out and live. Those others include us, her very lucky readers.” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, quoted in Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014).

Photos by Brenda Barry, taken on a recent walk on a wetland trail in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. I’ll be back next Friday with details about my new blog series, “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which launches on June 20th.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?” (Photos from my trip to Oxford, Mississippi)

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

May 31, 2024

“Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off?”

In Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass & Purveyor of Fine Footwear, by Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Molly isn’t sure if she’s falling in love with a man she has nicknamed “the Penguin Man.” If she is in love with him, she wonders if she’ll have to read the books he likes:

Am I in love with the Penguin Man? Can you just like being with someone and not be in love with them? Could I have fallen in love with him and not known? What does love feel like? Aren’t there supposed to be sparks? Isn’t your heart supposed to race? Might the shared love of an author mean you’re supposed to be with someone? Would he expect me to read Steinbeck? Would an expectation to read Faulkner be far off? Is that what love does to a person?

(I wrote about Molly of the Mall last year: “Oh, novels! What would I do without you?”)

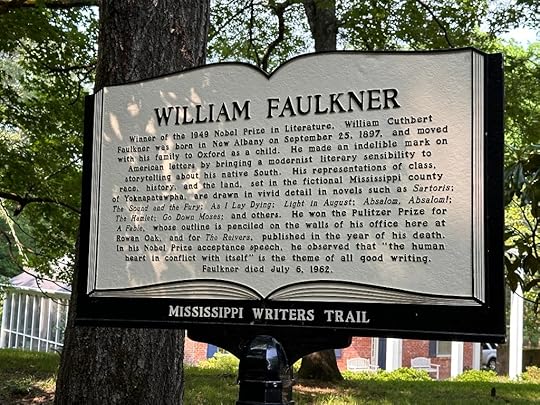

I was thinking of Molly last Saturday when I visited William Faulkner’s house, Rowan Oak, in Oxford, Mississippi.

I was in Oxford for a week, visiting my sister Bethie and her family, who moved there last summer after several years in Bonn, Germany. If you were following my blog last year, you might remember that when I visited Bethie there, she and I used to go for “coffee with Beethoven” in the Münsterplatz in Bonn. There’s a lovely café right next to the Beethoven statue. In Oxford, the café we went to was on the opposite side of the town square from the Faulkner statue, but it’s still pretty close, and on Saturday morning, we had “coffee with Faulkner.”

Bethie took this photo of Faulkner and me

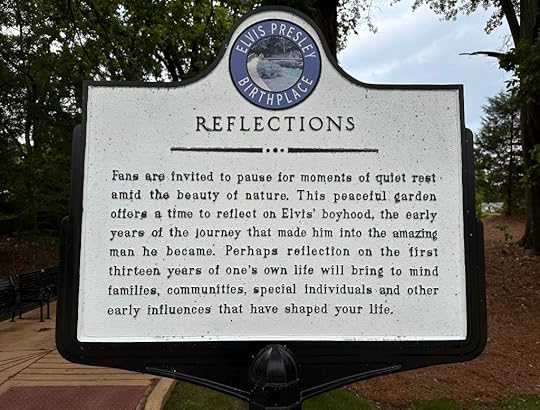

In the afternoon, I took my nieces to visit Rowan Oak, and we enjoyed exploring Faulkner’s house and gardens and the surrounding woods. I’ve read very little of Faulkner’s work and, like Molly, I’m not sure I want to start reading more. Nevertheless, I was interested to learn about the house, his office, and his family. I thought you might like to see some of the photos I took at Rowan Oak and elsewhere in Oxford. We also made a quick trip to Tupelo, where we visited Elvis Presley’s birthplace museum, and I’ll include those photos as well.

“… writing is a solitary job—that is, nobody can help you with it, but there’s nothing lonely about it. I have always been too busy, too immersed in what I was doing, either mad at it or laughing at it to have time to wonder whether I was lonely or not lonely, it’s simply solitary. I think there is a difference between loneliness and solitude.” (Faulkner at the University of Virginia, 1958)

“It was 1923 and I wrote a book and discovered that my doom, fate, was to keep on writing books: not for any exterior or ulterior purpose: just writing the books for the sake of writing the books….” (Foreword to The Faulkner Reader, 1953)

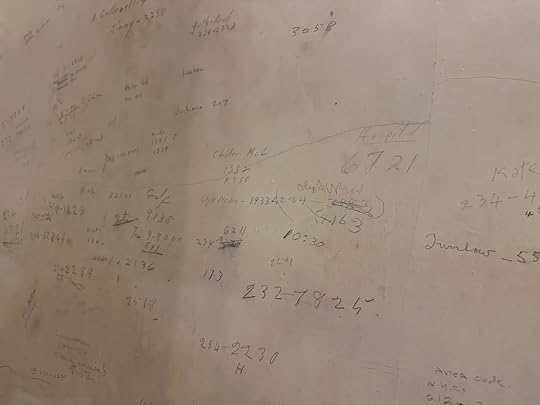

Faulkner liked to write on the walls of his house. Next to the telephone, he recorded phone numbers.

On the walls of his office, he wrote the outline of the plot for his novel A Fable, in graphite and red grease pencils.

“… of course the first thing, the writer’s got to be demon-driven. He’s got to have to write, he don’t know why, and sometimes he will wish that he didn’t have to, but he does.” (Faulkner at the University of Virginia, 1957)

English knot garden at Rowan Oak

I was interested to read that Faulkner hated air conditioning. His wife Estelle had an air conditioning unit installed in the window of her bedroom the day after his funeral. There’s a whole story behind that tiny detail. Makes me think of this famous six-word story: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” (often attributed, probably incorrectly, to Ernest Hemingway).

In this case, I’d say: “Faulkner is dead. Let’s get A/C.”

A radio sits on the table next to the bed in Faulkner’s daughter Jill’s room. There’s a story here, too: Estelle gave the radio to Jill after Jill had had a “bitter fight with her father about technology,” according to the description posted on the wall outside the room.

Flowers in the Square in Oxford

Square Books, Oxford, MS

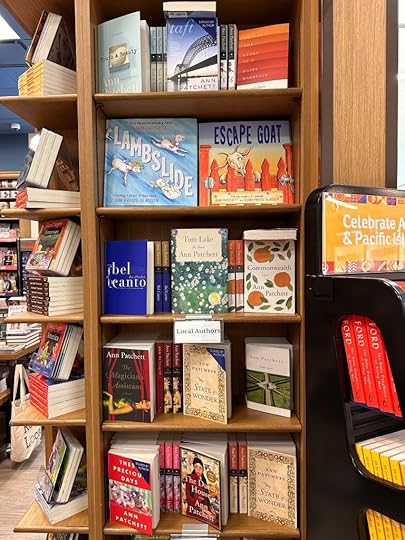

I had coffee at Square Books twice on this trip, once with Bethie and once with my friend Susan Allen Ford. I was delighted that Susan came to Oxford to see me. We’ve met up over the years at JASNA AGMs all over North America, but had never had the chance to meet in Mississippi, where she taught for many years at Delta State University. Susan’s book What Jane Austen’s Characters Read (And Why) will be published in July and I’m excited to read it. She’s writing a guest post for my blog series “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.”

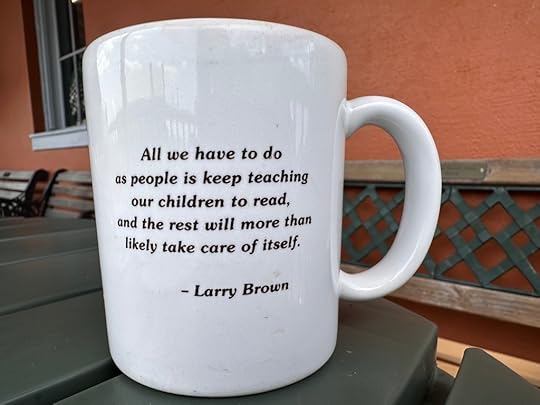

At Square Books, my coffee was served in mugs featuring quotations from Larry Brown and Eudora Welty. I didn’t get the mug with the Faulkner quotation about the tools he relied on to help him write: “paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey.”

“… it’s living that makes me want to write, not reading—although it’s reading that makes me love writing.”

– Eudora Welty

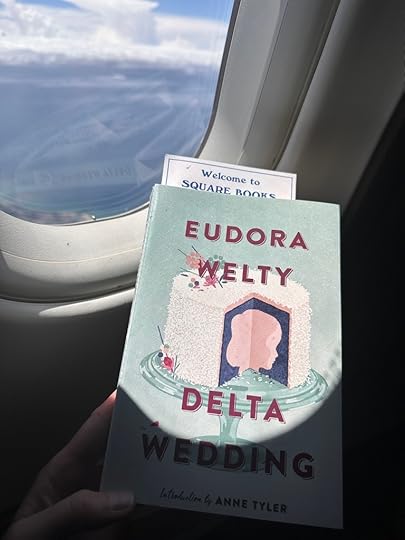

I also didn’t buy a Faulkner novel to read on the plane on the way home; instead, on Susan’s recommendation, I bought one of Eudora Welty’s novels. And Bethie bought me the Eudora Welty mug.

It took a long time to get from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Oxford, Mississippi, and back again—I flew to Nashville and then drove for about four and a half hours through Tennessee and Northern Mississippi—but it was worth it and I’m already looking forward to the next trip to see Bethie in her new home.

Flying into Nashville

The bend in the road in Mississippi

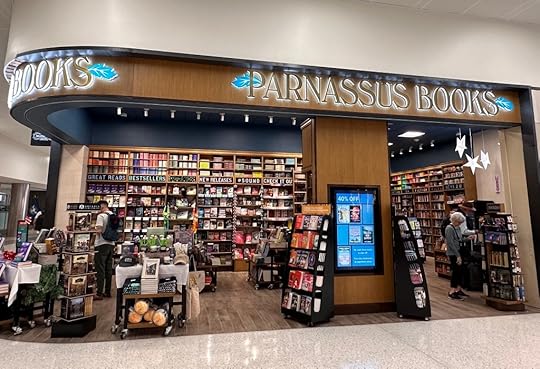

There’s so much more I could say about the trip—I haven’t even mentioned the Old-Time Piano Playing Contest and Festival that my niece and I went to last weekend, for example. I could also say more about Parnassus Books, at the Nashville airport, and about the University of Mississippi campus.

In the Nashville airport

Northern Catalpa Tree on the University of Mississippi campus

But this is already a long post, so I will end here with some photos from Elvis’s birthplace in Tupelo, and a photo of the sunrise from the airport hotel in Halifax, the night before I left for the long journey to Oxford.

The house where Elvis was born

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to my last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Posts by others who participated in #ReadingKilmeny:

From Hopewell’s Public Library of Life:

Review: Kilmeny of the Orchard, by Lucy Maud Montgomery

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

From Naomi at Consumed by Ink:

#ReadingKilmeny: “She was, after all, nothing but a child…”

From Simpler Pastimes:

May 24, 2024

“A beautiful voice” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“I am not afraid of you now.” These are Kilmeny Gordon’s words the first time she responds to Eric Marshall in L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard (Chapter 7). She cannot speak, and thus she writes to him on a slate that she carries with her everywhere. The first time she saw Eric in the old orchard, she ran away from him. This time, she stays, and the next time, she brings her violin and plays “an airy delicate little melody that sounded like the laughter of daisies” (Chapter 8). Kilmeny communicates most clearly through her music.

Gardens of Hope, New Glasgow, PEI

Please join my friend Naomi and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here. My first two posts on the novel were “A murmur that rings for ever” (#Reading Kilmeny) and “A rather doubtful experiment” (#Reading Kilmeny).

Elizabeth Rollins Epperly points out that “The narrator tells us that she writes little notes that show wit and humour, but we are never given any of these, and Kilmeny remains a beautiful picture,” even—spoiler alert—at the climactic moment when she warns Eric that his life is in danger (The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass). “In keeping with formula-romance roles,” Epperly writes, “Kilmeny does not have to do anything but look beautiful and act sweet for the world to be hers.”

Eric’s doctor friend, David Baker, turns out to be right that there is nothing wrong with Kilmeny’s vocal chords, and that a desperate need to speak will prompt her to do so. Once she has warned Eric, she finds that speaking is easy for her: “it seems to me as if I could always have done it.” Not surprisingly, she has “a beautiful voice—very clear and soft and musical” (Chapter 18).

I was interested to read Mary Henley Rubio’s suggestion that some of what happens in the novel parallels what was happening in Maud Montgomery’s life when she was writing it: Ewan Macdonald was courting her, and his courtship “allowed her to move beyond formulaic short stories and sentimental poems.” Rubio writes that “By freeing her from the fears of becoming a pitiful and voiceless old maid, Ewan’s love made her imagination soar and her pen sing” (Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings).

Ironically, however, although Montgomery may have felt more free to create Anne Shirley and other free-spirited girls and young women, Kilmeny is not like these heroines. Although Kilmeny of the Orchard is about a woman finding her voice, she is still bound by convention, and sometimes it seems that Kilmeny is barely allowed to be a character in her own story.

In the last chapter, after Kilmeny has discovered her voice and agreed to marry Eric, his father comes to meet her. Although Eric professes to love Kilmeny’s music and her voice, ultimately her beauty is shown to be more important. His father is skeptical about Eric’s choice, and Eric insists that he need only wait until he has seen her, for then he will understand. The two of them go to meet Kilmeny in the orchard, and this woman who has at last found her voice says—nothing at all.

Early in the novel, Kilmeny communicated by playing the violin and writing notes on her slate. In the end, she is shown reading—not writing, speaking, or playing music. Her figure, hair, and face are described in detail: it is her exceptional beauty, not her talent, her character, or her voice, that persuades Eric’s father she is the ideal bride for his son.

One way of ending this romance novel would have been to show Kilmeny speaking with her beloved. The girl who could not speak is transformed by true love: the story moves from her silence and isolation to a time in which she has captured the power of speech and will live happily ever after with the man she loves.

Instead, the ending is chilling. Kilmeny is shown without her violin or her slate. She could speak, but she does not. The ending is even more disturbing if we return to the parallels with Montgomery’s own life. Ewan’s courtship was a new beginning, but the freedom she found was limited.

I’m interested to hear what you think of Kilmeny of the Orchard—in the comments on this post, or on social media (Facebook; Instagram), or on your own blog. Thanks for reading with us!

I’m in Mississippi this week, visiting my sister Bethie and her family (and discussing Kilmeny, and admiring the spectacular magnolias). In my next post, I’ll share some more photos from the trip.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

“The murmur that rings for ever” (#ReadingKilmeny)

Posts by others who are participating in the readalong:

From Hopewell’s Public Library of Life:

Review: Kilmeny of the Orchard, by Lucy Maud Montgomery

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble