Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 8

September 8, 2024

A book signing and other celebrations

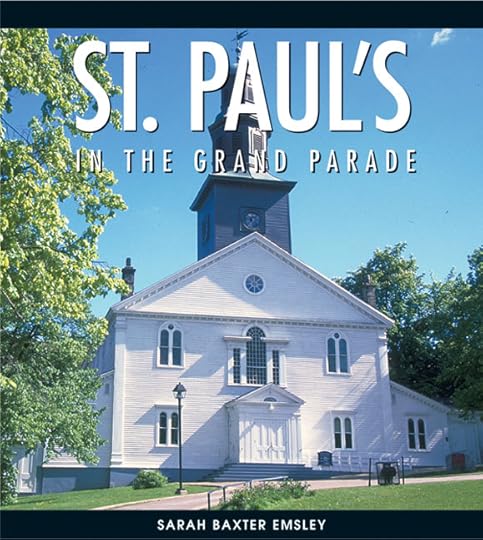

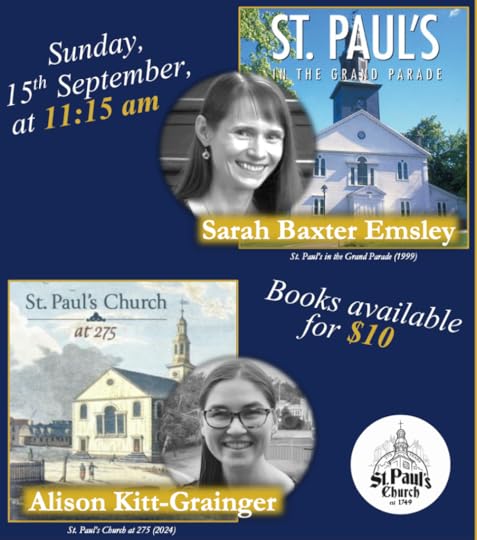

Next Sunday, September 15th, I’ll be signing copies of my book St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade, which I wrote for the 250th anniversary of St. Paul’s Church, the oldest building in Halifax, Nova Scotia and the oldest existing Anglican place of worship in Canada.

Jane Austen’s niece Cassy Austen was baptized at St. Paul’s on October 6, 1809, when her father, Captain Charles Austen, was serving on the North American Station of the British Royal Navy. You can find out more about Jane Austen’s connection with Nova Scotia in the “Austens in Halifax” walking tour my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred and I created.

On September 15th at 11:15, after the morning service, the official opening of the church’s 275th year, Alison Kitt-Grainger will be signing copies of St. Paul’s Church at 275 and I’ll be signing St. Paul’s in the Grand Parade. (Where did those 25 years go, I wonder??)

All are welcome! The location is 1749 Argyle St., across from City Hall in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Visit the St. Paul’s website for more details about the event. The guest of honour at the service will be the Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada, Archbishop Linda Nicholls.

Regular readers of my blog know that I like to celebrate significant anniversaries and special occasions. For example, for the 100th anniversary of Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel The Custom of the Country, which I edited for the Broadview Literary Texts series, I wrote a series of posts, including one on “What Edith Wharton Tells Us About the Way We Live Now.”

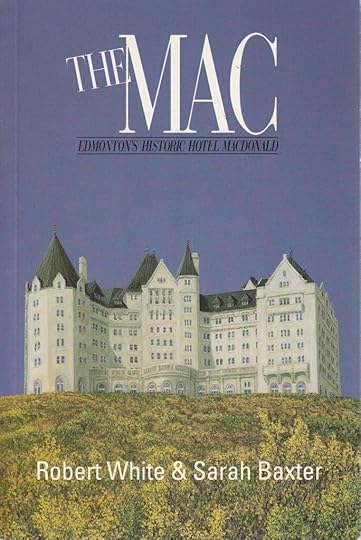

That same year, 2013, I started hosting blog series celebrations for novels by Jane Austen, for the 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice, but my interest in anniversaries goes back further, to the 250th anniversary of St. Paul’s Church in 1999 and, even before that, the 80th anniversary of the Hotel Macdonald in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1995 (the subject of my first book).

I do realize that my current “Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” blog series doesn’t match up with a milestone anniversary year (unless we redefine “milestone” so that 213 counts?)—I missed the chance to celebrate the 200th anniversary back in 2011 and thought I’d make up for that now. With the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, this year seemed like a good time to celebrate her first published novel. It’s been a great pleasure to read and share all the guest posts to date, and I’m excited about the remaining posts in the series. This week, we’ll hear from Diana Birchall and L. Bao Bui; next week, we’ll hear from Cheryl Bell and Janet Todd.

The next blog series celebration will begin on October 30th—the 213th anniversary of the date Sense and Sensibility was published—with a guest post from Kate Scarth, Chair of L.M. Montgomery Studies at the University of Prince Edward Island. Her essay on “Anne Shirley and Marianne Dashwood, #KindredSpirits” will link the summer S&S series with the celebration of L.M. Montgomery’s 150th birthday that will run through the month of November.

That’s a lot of celebrating! I do love bringing people together to celebrate these amazing writers, and while putting these series together takes a lot of time, it feels like time well spent. It always means a great deal to me to hear from readers who are enjoying the guest posts.

In fact, I enjoy organizing blog series celebrations so much that when the Jane Austen Society of North America asked me to co-host a celebration of Austen’s 250th next year on the JASNA website, I said yes. We have some fabulous tributes to Jane Austen lined up already and I’m excited to share them with you. More on that celebration soon….

Many thanks to all who are participating in these celebrations by writing, reading, and joining in the conversations! I’m glad you’re here. And I hope to see some of you in person next Sunday at St. Paul’s.

Thank you to Brenda Barry for the beautiful photos of astilbe and phlox that appear above, taken recently in the Historic Gardens in Annapolis Royal, NS.

For today, I am taking a break from reading, writing, editing, and email to go for a hike and eat cake and ice cream with my family. It’s my birthday—and International Literacy Day! More reasons to celebrate. I’ll leave you with a couple of photos of the cakes my daughter made for my birthday last year, along with a photo of this year’s birthday flowers.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

An Ill-disposed Narrator? Backhanded Insults in Sense and Sensibility, by Kathy Cawsey

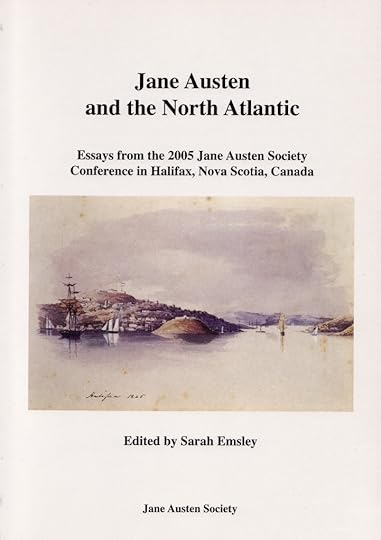

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 6, 2024

The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price, by Theresa Kenney

Marianne Dashwood has risen in the estimation of audiences and critics to the point where some believe if Austen changes her character, Marianne’s “reduction” is a punishment for what we now consider admirably romantic and passionate behavior. The novel’s own Colonel Brandon models such an interpretation, telling Elinor in Chapter 11, when inquiring about Marianne’s belief that a second attachment in life is impossible,

“ . . . but a change, a total change of sentiments—No, no, do not desire it,—for when the romantic refinements of a young mind are obliged to give way, how frequently are they succeeded by such opinions as are but too common, and too dangerous! I speak from experience. I once knew a lady who in temper and mind greatly resembled your sister, who thought and judged like her, but who from an enforced change—from a series of unfortunate circumstances” —Here he stopt suddenly. . . .

But of course, if he is to marry Marianne by the end of the novel, Marianne’s sentiments on exactly this point must change. Until Alan Rickman played the lovelorn Brandon, marriage to that character seemed a punishment for the ebullient Marianne. Just look at the aggravating advice the BBC 1981 Colonel Brandon gives Marianne to read “the majestic Milton, and the demi-god, Shakespeare,” which Marianne later dutifully parrots to her mother. Marianne loses all her energy and self-confidence and her prize is the dull middle-aged man with lambchop whiskers.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-fourth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Is change necessary in the heroine of a novel? Some have argued that Elinor cannot be the real heroine of the novel because she doesn’t change. Her stoic resignation and self control seem to be something Austen reinforces and rewards, without convincing us that they save her or her family from any pain or that they produce satisfying poetic justice, since they only procure for her the Delaford parsonage and the unexciting Edward Ferrars. Harkening to the norms for heroes and heroines YouTube creative writers purvey, my students tell me characters cannot be protagonists if they do not mature between the beginning and the end. Holding either opinion ill prepares the reader for understanding Sense and Sensibility, or indeed any of Austen’s “quiet” heroines. Austen was not bound by the rules that content creators share so freely with would-be novelists and manga cartoonists of today. Neither were Homer or Shakespeare, for that matter.

However, what is Marianne’s status in the novel that we believe once bore her name as well as her sister’s? Is she the hidden heroine or is she merely the inferior second sister who must become like the eldest to arrive happily at the conclusion of her story?

I have been thinking a great deal about Marianne’s similarity, not to Elinor, but to the heroine of another novel Austen wrote over a decade later, Mansfield Park, and that character is another teen who loves early romantic poetry, Fanny Price. Given the astonishing similarities between them, it is surprising how warm the affection for Marianne is among readers and how heated the disapproval is of Fanny. Comparing and contrasting the Steventon novel romantic, Marianne, with the Chawton novel romantic, Fanny, shows Austen maintaining her interest in certain problems from the 1790s until 1814, and helps us understand the widely disparate reactions to the two young women.

First, readers should see that Austen understands the romantic enthusiasms of both Marianne and Fanny as typical behavior for a teenaged reader. “‘Dear, dear Norland!’ said Marianne as she wandered alone on the last evening of being there. . . . And you, ye well-known trees!—but you will continue the same.—No leaf will decay because we are removed . . . you will continue the same: unconscious of the pleasure or the regret you occasion, and insensible of any change in those who walk under your shade’” (Volume 1, Chapter 5).

Fanny similarly rhapsodizes before the outing to Mr. Rushworth’s estate at Sotherton (her own word for this kind of speech in a later conversation with Mary Crawford): “Cut down an avenue! What a pity! Does not it make you think of Cowper? ‘Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.’” (Volume 1, Chapter 6; Book I of The Task, “The Sofa,” lines 338-39).

Lamenting over trees is clearly the job of the sensitive soul. But how much of this is internalized aesthetics and norms, how much is performance? Isabella Thorpe’s performance of sentimentality in Northanger Abbey has perhaps already formed a lesson in sincerity for the Austen reader, even if one has not read the juvenilia, which are full of such parodies of performed emotional sensitivity. Marianne’s love for what teenaged girls love is partly performative; I think this is a fault Austen believes teenagers can fall into if they are enthusiastically bookish, as Marianne is, or if they must be so to fit into a social group, as Isabella Thorpe seems to be. Her bookishness itself is also performative, which Marianne’s is not. It has been suggested by some scholars that Isabella has not even read the books on her friend Miss Andrews’s list in Chapter 6; she and Catherine Morland never make it through Udolpho!

Austen does not seem to dislike Marianne’s love of the melancholy in nature, but she does point out that Marianne judges others harshly if they lack it. Edward will teasingly point out, “It is not every one who has your passion for dead leaves” (Volume 1, Chapter 16) and in doing so, he may mark himself as unromantic, but the fact that Austen thought up his line shows she dislikes the performative nature of this “passion.”

At least we can say if it is an element in Marianne’s character that all the older characters but her mother have tempered since that age, if they ever had it, Austen imagines it a passing fad indicative of the character’s youth. Marianne’s reading of her sources is undigested as of yet. And yet she has already known real sorrow. In their focus on Marianne’s heartbreak over Willoughby, readers forget she has just lost her father and the Dashwood family is in mourning for him through most of the timeframe the novel covers.

Fanny Price’s passion for romantic poetry and the sentimental attitudes its heroines exhibit is perhaps an element Austen considers appropriate in depicting her as a rather naïve teenager. Vladimir Nabokov wrote discussing Fanny’s frequent quotations of or allusions to poetry, especially in conversations with Edmund. He says,

. . . we must bear in mind that in Fanny’s time the reading and knowledge of poetry was much more natural . . . and widespread than today. Our cultural, or so-called cultural, outlets are perhaps more various and numerous than in the first decades of the last century, but when I think of the vulgarities of the radio, video, or of the incredible, trite woman’s magazines of today, I wonder if there is not a lot to be said for Fanny’s immersion in poetry. (Lectures on Literature, Mariner Books, 1982)

However, thinking of poetry generally leads Fanny, unlike Marianne, to contemplation of deep issues. She does not stall in rapturous imitation. Though her exclamations may have a tinge of the imitative, her references are quite consciously quotations, and because she is merely sharing her enthusiasm with Edmund, who has read the same works without apparently wishing to be seen as a romantic hero himself, it seems less as if she is acting out a learned part.

In “‘My idea of a chapel’ in Jane Austen’s World,” Sarah Emsley notes Fanny starts with a romantic idea of a place but concedes to Edmund’s preference for definition by way of function (Persuasions 24 [2002]). Her willingness to accept correction about her expectation that a Sir Walter Scott-like “Scottish monarch” ought to be “sleep[ing] below” in their discussion of the plainness of Sotherton chapel demonstrates that Fanny doesn’t cling to fantasy. This remains the case even if Fanny has “very acute” “feelings” and bursts into tears frequently (she is in tears at least twelve times in the novel). She, like Marianne, starves herself a bit (Marianne when in London and at Cleveland out of imitation of romantic heroines, as she herself admits to Elinor later, Fanny because of her far more realistic unease at the dirt in Portsmouth), but Fanny does not get close to death as Marianne does by means of her desire to be a romantic heroine. I submit that the readership of Mansfield Park would find Fanny a more sympathetic heroine if she would just be a little more sick and if she were surrounded by people who make much of her when she is sick rather than the harping Aunt Norris who accuses her of playing tricks and exaggerating her illnesses.

Perhaps the most important difference between the two girls is the objects of their affections. Marianne allows herself to be deceived by an immoral man because of the strength of her emotions. Fanny does not. Jane Austen’s sister Cassandra, like so many readers since, wished her to marry Henry Crawford. Their niece later recalled Jane’s persistence in her decision about the conclusion (Louisa Knight “remembers their arguing the matter but Miss Austen stood firmly and would not allow the change” [Deidre Le Faye, Jane Austen: A Family Record, Cambridge UP, 2004]). Fanny is heart whole in the end, unlike Marianne, her abandonment by Edmund temporary and mended. Might it be that, to the reading audience, the damaged heroine is preferable? The heroine who makes mistakes about a man’s proclivity for dalliance is the soft-hearted one with whom many readers can sympathize. The heroine who is not mistaken about that seems too self-assured, too stubbornly right for many readers to like her much. Jane Austen might just be asking, as she turns her attention in the later novel to a girl with a love for romantic poetry and a conviction of “how wretched, and how unpardonable, how hopeless, and how wicked it was to marry without affection” (Volume 3, Chapter 1), “Do we read a novel like Sense and Sensibility hoping the man will traduce the girl?” As in the audience’s general reaction to Isabella in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, the reader’s reaction to Fanny may be less enthusiastic than that to Marianne because Austen portrays the later heroine as untraduced under erotic pressure. But does that really prove that we want women to be victims?

Quotations are from the Cambridge editions of Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, and Mansfield Park, edited and with an introduction by Barbara M. Benedict and Deirdre Le Faye (2006); Edward Copeland (2006); and John Wiltshire (2005).

Theresa Kenney holds a BA in English and Classics from Penn State, a Master’s from Notre Dame and a PhD from Stanford. Professor of English at the University of Dallas, she has published on Austen, Brontë, Dante, Dickens, Donne, and Southwell, among others. Her main fields of interest are Medieval lyric and romance, Arthurian literature, the Metaphysical Poets, and the nineteenth century novel. She translated three Renaissance treatises on whether women have souls in Women Are Not Human: An Anonymous Treatise and Responses, and co-edited and contributed to The Christ Child in Medieval Culture: Alpha es et O! Her monograph All Wonders in One Sight: The Christ Child Among the Elizabethan and Stuart Poets came out recently from University of Toronto Press, which is also publishing her upcoming book Last Impressions: Jane Austen’s Endings.

She and her husband live near Dallas with their two daughters and Siberian cat and often visit her husband’s native Ireland, with excursions to the Irish locations at which many a Jane Austen film was shot. Theresa contributed the photos for this post, many of them taken in her parents’ backyard in State College, PA. She says, “The yellow and white iris is Alpine Journey and the white is Immortality. The white and purple is Brilliant Idea! The little blue scilla is Glory of the Snow or Schneeglanz. The white rose is a wild one—we don’t know the name. The red is our quince bush.” The photos of autumn trees and dead leaves were taken in Tom Tudek Park, Ferguson, PA.

Theresa also sent a collage her friend Christine Desmond Cleary put together when they visited Higginstown House outside Trim, Co. Meath, where they met the family, who gave them a personal tour. She writes that “Higginstown House is the location of the drive Jane and Tom ‘elope’ from in Becoming Jane and the interior is where the Morland family talk with the Allens and greet Henry Tilney in the 2007 Northanger Abbey.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “What Did Lucy Steele?” is by Diana Birchall.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

An Ill-disposed Narrator? Backhanded Insults in Sense and Sensibility, by Kathy Cawsey

Sense and Sensibility Hearkens Back to Its Origins, by Collins Hemingway

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

September 3, 2024

An Ill-disposed Narrator? Backhanded Insults in Sense and Sensibility, by Kathy Cawsey

Jane Austen’s use of “free indirect discourse” has been examined and (rightly) praised by critics, but on this read-through I noticed a sub-technique of that discourse—what I will call the “backhanded insult.” If a backhanded compliment is an actual compliment that carries the undertones of an insult—“Wow, I really like what you’ve done with your hair, I never thought you could look so pretty!”—a backhanded insult is an actual insult that sounds like a compliment. The recipient has to think about it before understanding that they’ve been insulted.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-third guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

The most obvious example of this kind of insult comes on page three of the book, when John Dashwood is encountered for the first time: “He was not an ill-disposed young man, unless to be rather cold hearted and rather selfish is to be ill-disposed” (Volume 1, Chapter 1). The OED defines “ill-disposed” as “Having a bad disposition; disposed to evil or harm; immoral, wicked; malignant, malevolent.” John Dashwood is not deliberately malignant or malevolent, but as the story goes on it becomes evident that his cold-heartedness and selfishness do dispose him to evil and immoral acts towards his half-sisters, which cause very real harm. The reader wonders what the heck “ill-disposed” means, if it does not mean “cold-hearted and rather selfish”—and so the seeming compliment of not being ill-disposed actually turns into an insult.

This kind of complicated insult abounds in Sense and Sensibility. At the beginning of the next chapter, John Dashwood treats his half-siblings with “as much kindness as he could feel towards any body beyond himself, his wife, and their child” (Volume 1, Chapter 2). Again, a backhanded insult—the reader thinks that he shows them as much kindness as he could feel, before considering that he may, in fact, be able to feel none.

Another famous phrase describes Mrs. Ferrars: “she was not a woman of many words; for, unlike people in general, she proportioned them to the number of her ideas” (Volume 2, Chapter 12). In the context about a book contemptuous of people who talk too much, this starts out as a compliment—but then has a twist of a double hidden insult. Both “people in general”—who talk more than they think—and Mrs. Ferrars—who barely thinks at all—get pilloried.

Deborah Yaffe wrote in this summer party series about the “darkness” that is at the centre of Sense and Sensibility. The humour of this book is part of this darkness: the backhanded insults are funny because we share the joke with the narrator/Elinor, on people who are less intelligent, less astute, less clever than we all are.

Sense and Sensibility is, I think, most easily (and most often) paired with Pride and Prejudice—and not just because of the alliterating, thematically suggestive, enshrined contradictions of the titles. Of all Austen’s books, these two are the most similar: both have a pair of sisters at their core; both explore two radically different ideas of love, marriage, and romance; both address the delicate balance of inner personal desire and integrity with the external pressures of society, family, finances. But the “free indirect discourse” is used very differently.

In Pride and Prejudice, yes, the indirect discourse is almost always channeling Elizabeth’s understanding of the world and its people, yet those opinions are accompanied by details of plot that confirm those judgements. So, for example, when in the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice we are told that Mrs. Bennet “was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper,” we later see the results of Mrs. Bennet’s silliness and changeability in the way she treats Mr. Wickham, or Mr. Bingley, or Lydia.

In Sense and Sensibility, by contrast, we are given judgements and opinions that are rarely supported by the actions of the characters. At times, the actions themselves are described in a way that seems to support the judgments given in the free indirect discourse, but when the narrator’s—or Elinor’s?—assumptions about the motivations behind the actions are removed, the actions become far less reprehensible.

For example, one of the funnier passages in the book is when Robert Ferrars goes into a three-page discussion of the merits of cottages. The narrator says, “Elinor agreed to it all, for she did not think he deserved the compliment of rational opposition” (Volume 2, Chapter 14), because she assumes he is a silly, self-important man who likes to hear himself talk. But what if he were just awkwardly trying to put people at ease who had to live in cottages? Likewise, the narrator imputes selfish impulses to the constant balls and parties and entertainments Sir John provides, without once thinking how grateful the surrounding community must feel at his shouldering the expense and trouble.

Or take Lucy Steele. We are told that “her features were pretty, and she had a sharp quick eye, and a smartness of air, which though it did not give actual elegance or grace, gave distinction to her person” (Volume 1, Chapter 21). “She ain’t pretty, but she looks that way”—what else is prettiness but a way of looking? What is “elegance” or “grace” but “distinction” and “smartness of air”?

The narrator—or Elinor?—is always attributing selfish and base motives to Lucy’s actions. The Steele sisters receive sneering criticism for the “constant and judicious attention [with which] they were making themselves agreeable to Lady Middleton” (Volume 1, Chapter 21). Elinor holds them in contempt for going along with the misbehaviour of Lady Middleton’s children. But how else are they supposed to behave towards their hostess’s offspring when they are guests? (I reread Emily of New Moon a few weeks ago, and this passage reminded me of the incident when both Emily and the New York authoress politely ignore the bad behaviour of a dog each believed belonged to the other.)

I suppose there is evidence for Lucy’s selfish motives at the very end of the book, when she ditches the outcast Edward in favour of his rich brother—but even that is dubious. Surely if she were just out for money, she would have asked to be released from the engagement as soon as Edward was disinherited; yet instead, according to her sister, “she told him directly, she had not the least mind in the world to be off, for she could live with him upon a trifle, and how little so ever he might have, she should be very glad to have it” (Volume 3, Chapter 2).

Elinor’s own motives are not so different from those she imputes to Lucy. When she objects to staying with Mrs. Jennings, she says, “though I think very well of Mrs. Jennings’s heart, she is not a woman whose society can afford us pleasure, or whose protection will give us consequence” (Volume 2, Chapter 3). Shunning someone who has a good heart because she’s worried about “consequence” is not exactly disinterested.

And Mrs. Jennings, more than any other character in the book—Elinor included!—acts from generous, selfless motives. She invites two poor girls to stay with her indefinitely, even though they won’t even tell her whether they prefer cod or salmon for dinner. She fusses about how little Edward and Lucy will have to live on, and resolves to loan them her own maid and get them some furniture. And she insists on staying while Marianne is ill, and treating her as though she were her own child.

Yes, I laughed with Elinor and enjoyed her snide, snobby remarks and clever turns of phrase. But I’m afraid that I, too, would fall far short of her high standards.

All quotations from both books are taken from the Arcturus Publishing editions, 2023.

Kathy Cawsey reads books, writes books about books, and talks about books (mostly medieval) at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. She contributed the photos.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “The Real Romantic? Marianne Dashwood and Fanny Price,” is by Theresa Kenney.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Sense and Sensibility Hearkens Back to Its Origins, by Collins Hemingway

Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility, by Sandra Barry

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 30, 2024

Sense and Sensibility Hearkens Back to Its Origins, by Collins Hemingway

When I read Jane Austen or any other good author, I peer through two different lenses. The first is that of an ordinary reader looking to enjoy the story, the characters, and the writing. I settle in and luxuriate in the text like everyone else. The second is that of a fellow writer. I examine the way Austen structures each scene, the way she describes people, the way she sets up character interactions and thoughts.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-second guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer—three more weeks. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here. I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

This second approach might be termed an assessment of choices, because every decision a writer makes will send ripples through the entire work, affecting everything to come. Almost always, I conclude that Austen has made not only a good choice but the best of many possible choices. A few times, however, I come upon a revealing irregularity. Some are significant. Both Northanger Abbey and Persuasions have serious structural problems, though for substantially different reasons.

Exploring these uneven areas in an otherwise polished composition can lead to a new understanding of the writer’s craft, as Virginia Woolf points out in The Common Reader. Austen’s juvenilia and unfinished works provide insights into her masterpieces, Woolf says, because in the lesser works “her difficulties are more apparent, and the method she took to overcome them less artfully concealed” (136-37).

Rough patches provide the entry point for examination. Why, I wondered, is the major character Edward Ferrars practically invisible in the first five chapters of Sense and Sensibility? We have only indirect descriptions of Edward, mostly through what Elinor and Marianne say about him. Though Elinor falls in love with him, we do not see them interact—or see him take part in any scene. I’m hard pressed to count his one remark—“Devonshire! Are you, indeed, going there? So far from hence! And to what part of it?”—as participation in a scene (Volume 1, Chapter 5). Until he speaks, there’s been no indication that he is even in the room.

I mulled his lack of presence for some time until realizing that none of the major characters is described in the Norland chapters. Not even John and Fanny Dashwood are depicted physically in their indecently funny swindle of John’s stepmother and half-sisters out of any benefaction from his inheritance. Then I remembered the novel’s origin in the epistolary form as Elinor and Marianne. I realized that, in a letter, you would not describe people that your correspondent already knew. You would describe only the people you would newly meet.

Which is why the minor characters at Barton Park receive decent descriptions while the major members of the cast do not. In a letter, you would mention only something unusual about known personages, such as Marianne’s stormy injury and dashing rescue.

How much more evidence of the epistolary remained? I wondered.

I have employed the epistolary mode in places in my own fiction, and I have written about its strengths and limitations (“Allure, and Danger, of the Epistolary: From Richardson to Lady Susan” [Sensibilities, June 2024]). Would Austen have chosen Samuel Richardson’s exciting “to the moment” epistolary style, or would she have used the discursive mode of Tobias Smollett and Frances Burney? How would we identify the traces of either?

My first step was to canvass the literature to see what other commentators have uncovered. Brian Southam, Park Honan, and Deirdre Le Faye make passing references to Austen’s use of the epistolary. Southam provides a few examples in Sense and Sensibility (Literary Manuscripts 56), Honan observes that she did not “find it easy to expunge faults from her original epistolary” approach (Jane Austen: Her Life, Her Art, Her Family, Her World 275), and Le Faye says the form constrained her in Lady Susan (Family Record 89). None of them goes into detail about the epistolary material (nor did anyone else I could find), so I took on the task.

If Austen had completely revamped the chapters, finding remnants would be difficult. But I had already found enough of Honan’s unexpunged “faults” to believe that more evidence lay close at hand. There are, for example, short chapters that give contrasting points of views primarily from Elinor or Marianne. Could these have originated as an exchange of letters?

It took several readings, but I identified three distinct forms of the epistolary mode in the novel. The most obvious, but oddly the least important, are the remaining letters in the story. Another grouping includes an unusually large number of offstage incidents that are told to major characters. Such informational transfers happen often in the epistolary because they are the only way for critical plot information to be delivered to the letter writers, who can’t range as widely as a third-person narrator.

The third and by far the largest grouping is what I label “expositional” epistolary. A letter writer, real or fictional, will usually summarize ordinary moments, then expand in detail on exciting incidents. This is strikingly the pattern in Smollett’s epistolary Humphry Clinker. Converted to third person, this would become text that contains many pages of general exposition along with small buried or appended incidents. This is strikingly the pattern in many chapters of Sense and Sensibility.

In a 2022 article in Persuasions On-Line, I provide an expansive analysis of the three kinds of epistolary and their use in the novel (“Sense and Sensibility, Letter by Letter”); this essay is now a chapter in my new book about Austen’s development as a writer. In my view, about two-thirds of the book, mostly in the first and third volumes, has a clear epistolary origin. Rather than repeat my findings, I offer a “class exercise” to interested readers of Austen’s work.

Pick a stretch of six or eight chapters from anywhere in the book. Assess the nature of the text. How many chapters tell the story indirectly or contain long, generalized commentary? How many read like modern scenes with a great deal of character interactions and dialogue? Are there any chapters that appear to be hybrids?

What is your surmise for the reason for any differences?

Quotations are from the Oxford edition of Sense and Sensibility, edited by R. W. Chapman (1933).

Collins Hemingway is the author of the newly published Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in “a Style Entirely New,” a book that analyzes Austen’s development as a writer. Available through Jane Austen Books, the work illustrates what Austen learns from book to book about the art of fiction and how she applies the lessons in future novels. Collins has written eight other books, including historical fiction based on Austen’s life. He sent the photos, all taken in Central Oregon in June. The first, he says, is “an unusual iris in our front yard. Second is our dog, Winston the Westie, surveying the superfluity of the peonies in our front yard.”

Collins was recently interviewed by Breckyn Wood on Austen Chat (the Jane Austen Society of North America podcast) about his new book.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “An Ill-disposed Narrator? Backhanded Insults in Sense and Sensibility,” is by Kathy Cawsey.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility, by Sandra Barry

Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility, by Paul Gordon

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 27, 2024

Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility, by Sandra Barry

The first time I read any Jane Austen was in Grade 10 (1976-1977) at Bridgetown Regional High School, in Bridgetown, Nova Scotia. My English Literature teacher was Miss Ellen Corkum, fresh out of Teacher’s College and a favourite among the senior high students. She was a wonderful teacher, enthusiastic about literature, who encouraged us to think creatively about what we were reading. The project I did was on Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I am sure I wrote an essay, but what I remember most is spending weeks scouring magazines for images that somehow, in my view, represented the main characters. Then I created collages using the images. I remember cutting out pictures and words, arranging them on Bristol board, and meticulously lettering in the names of each character.

I suppose my essay was a kind of character analysis and the collages were a graphic complement to my words—so, a multi-media approach before I ever knew such a term. (Remember, there were no computers then, only magazines, scissors, glue and imagination.) I made collages for all the sisters, the parents and, of course, Mr. Darcy, with whom I fell in love! I remember feeling proud of my effort and I kept the collages for a long time. They are long gone now, lost in the drift of space-time. Even so, they remain vivid in my memory. I got an A. (Even the school itself is now gone, torn down, and nearby a new, state-of-the-art K-12 facility built, filled, I am sure, with computers and other wonders of modern technology.)

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-first guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

The long-term impact of this introduction was my intention to—outside any school requirement—read every Austen novel, some borrowed from the school library and some from the tiny public library in town. Eventually, I bought the Penguin paperback editions of all of Austen’s novels. (Alas, periodic culls of my library over the decades have meant that I passed on these volumes.) I do not remember when I first read Sense and Sensibility, but it was during my late teens or early twenties.

The other major impact of reading Austen was that it sent me on to the Brontës, Eliot, Dickens, James and other mid-19th century novelists. I progressed through the late-1800s until I reached an immersion in Woolf, whom I did study at university. But it all started with Austen and my fifteen-year-old self.

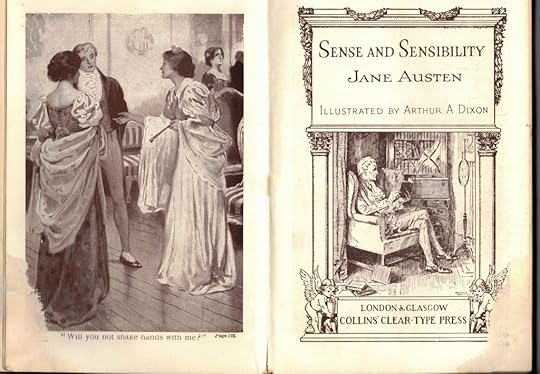

When Sarah invited me to write a guest post to help celebrate Sense and Sensibility, I was honoured and happy to agree, but it had been decades since I had read any Austen, being immersed as I have been for over thirty years in writing about the life and work of the poet Elizabeth Bishop. However, about two years ago, my sister Brenda (whose photos Sarah has shared on this blog and are in this post), also a big Austen fan, coincidentally found and bought a lovely little edition of this novel at a wonderful used bookstore in Bridgetown, Endless Shores.

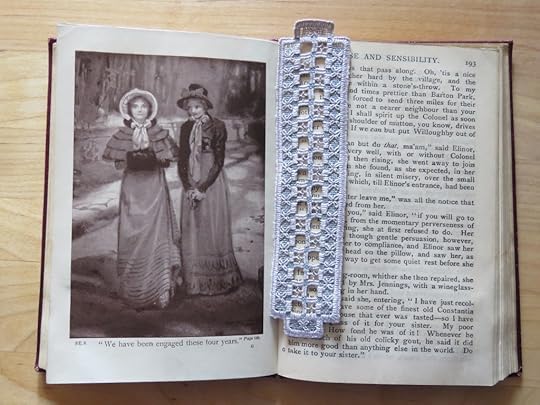

The volume is a Collins’ Clear-Type Press edition out of London and Glasgow, illustrated by Arthur A. Dixon. There is no publication date, but a rudimentary online search suggests it was published just after the turn of the 20th century, the time when Dixon was most active. It is a dear little book, only 6” x 4” with a leather cover, gold embossed words on the spine, onion skin paper and seven sepia illustrations: a lovely object to hold, just the kind of book one of Austen’s characters might hold and read in the evening in the drawing room. When Sarah invited me to contribute something, I picked it up and began to re-read it, at least four decades after first doing so.

In the interim my main Austen intake has been the movie and television adaptations of her books. I’ve lost track of how many we have watched (some better than others, and we have watched our favourite adaptations over and over again). So, it was a revelation to go back to the original words.

The primary revelation in this return was how leisurely the novel is, compared to the compression that must happen when translating to the screen. My perceptions of the characters were also challenged, so fixed have they become through the cinematic lens so ubiquitous these days.

I purposely re-read Sense and Sensibility slowly, a chapter a day, so I could ponder its quietly unfolding narrative. I could see where film-makers had lifted lines verbatim, removing them from Austen’s lush contexts. As I progressed, I tried to clear away the interpretations wrought by script writers, directors and producers. All readers bring their own sensibilities to any text (projecting, selecting, interpreting) and I wanted to let my own responses apply. And also, simply enjoy Austen’s charming, intricate, intelligent language.

Perhaps the most startling revelation for me came late, with the encounter between Elinor and the by then unhappily married Willoughby (while Marianne is still recovering). I had not remembered at all his long, self-serving explanation about his behaviour, his plea to be seen as one of the victims, his justifications which go on for pages—and Elinor’s patience and inclination, not fully conceded, to feel sorry for him. Forgive me for bringing my 21st-century sensibility to his egotistical moan: I mean, really Willoughby! It is a testament to Austen’s own keen sense of human behaviour and experience that the “happy ending” offered happens in the quietest of ways, almost as an afterthought.

I guess the question for me now is which Austen novel will I re-read next?

Sandra Barry is a poet, independent scholar and freelance editor. She is one of the founders of the Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia and her book Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s ‘Home-Made’ Poet was published by Nimbus in 2011. She and her sister Brenda spent last week at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, NS, where they had “time to sit for long stretches on the verandah and watch the sky and clouds and back pasture with its deer and birds.” Here’s a photo of that view, taken by Brenda:

This photo of Sandra (on the left) with Brenda and their friend Pam was taken by Greg Riley.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Sense and Sensibility Hearkens Back to Its Origins,” is by Collins Hemingway.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility, by Paul Gordon

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 23, 2024

Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility, by Paul Gordon

At first, I was hesitant to write the musical of Sense and Sensibility. I had just written Emma and for the next several years I was busy with productions across the country. I wasn’t sure I had another Austen musical in me. But when Chicago Shakespeare Theatre offered to commission me to write a musical of Sense and Sensibility, I couldn’t say no, as I knew the theatre’s stellar reputation and I felt Jane Austen and I would be in good hands.

And I was right.

I suppose this would be a good time to mention that up until this point I had not read Sense and Sensibility, I had only seen the Ang Lee film (one of my all-time favorite films), so reading the novel was quite a revelation. I can’t even remember now how long it took me to complete the first draft of the show, but as soon as I started reading the book, the music came pouring out of me.

(From Sarah: This is the twentieth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

When I musicalize a novel, the most important decisions are not what to include but what not to include. With Emma, it was immediately apparent to me that I didn’t need Knightley and Emma’s brother and sister, who are a large part of the novel. They would be mentioned, of course, but I didn’t need them to appear, and the musical works quite well without them. When John Caird (Les Misérables) and I were first working on Jane Eyre for Broadway, we made the mistake of trying to “perform the novel on stage.” Then we spent the next ten years trying to fix it, and we just kept removing bits of the story until it could be performed on stage in less than three hours! But in doing so, we learned a great deal about what makes good storytelling on stage.

With Sense and Sensibility these decisions were not as clear. There was far less dialogue in the novel than Emma, and this time around I would have to write many scenes from scratch instead of lifting Jane Austen’s brilliant dialogue. And, I had the movie in my head and I couldn’t conceive of cutting any characters. But as I went deeper into the novel and started leaving the film behind, I realized that I wanted to focus entirely on Elinor and Marianne and their relationship as sisters—and so I made the painful decision to cut Mrs. Dashwood and Margaret. But that turned out to be a great decision for the stage musical.

Once my first draft was complete, we did a series of “table reads” in Chicago with just a few actors and a piano. It gave us a great sense of the shape of the show, as we continued to ask ourselves questions: Is the story clear? Is this the right song? Do we understand this relationship? How do we support the storytelling?

We were getting close to opening night when Megan McGinnis, the brilliant actor who was playing Marianne, had an idea. She felt strongly that Marianne needed a ballad in Act II. I agreed with her immediately because it resonated with me. (I love working with smart actors who understand their characters better than I do at this point in the process.)

Megan felt that a pulsating up-tempo song after Willoughby rejects Marianne for Miss Grey was not quite right and she suggested a ballad that was more reflective of the pain the character feels in the moment. She was right, and so after rehearsal I went back to my hotel room and wrote “The Swing,” which instantly became one of my favorite songs in the show.

Making theatre is such a wonderful collaborative process. So very different from what Jane Austen must have felt when she was writing Sense and Sensibility. But what I love most about this process is that I get to be on both sides of it. I’m quite isolated while I’m writing the book and the score, but as soon as I get in a room with my fellow artists, new ideas spring forth and I get to enjoy the creative vibrancy of a room full of artists.

I’m so grateful, that in my small way, I have been able to share the genius of Jane Austen with theatregoers around the country. As we celebrate her 250th birthday next year, I will continue to dedicate myself to sharing her brilliance through the magic of theatre.

Most of the photos are from the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre production of Sense and Sensibility in 2016 (plus a hydrangea photo taken by Sarah).

Paul Gordon is a Tony Award nominated composer for his musical Jane Eyre. Other works include Sense and Sensibility (winner of the 2015 Jeff Award for Best New Work), Daddy Long Legs (2009 Ovation Award, 2 Drama Desk Award nominations, Off-Broadway Alliance Award nomination and 3 Outer Critic Circle award nominations). He is the co-founder of StreamingMusicals.com, where his musicals Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Estella Scrooge, Being Earnest and No One Called Ahead can currently be streamed. (Sense and Sensibility is also available on YouTube.) Knight’s Tale, written with John Caird, has had multiple productions in Japan. His other shows include: Stellar Atmospheres, Little Dorrit, Schwab’s, Analog and Vinyl, The Front, Juliet and Romeo, Sleepy Hollow, First Night, The Circle, Ribbit, Greetings From Venice Beach and The Sportswriter. In his former life, Paul was a pop songwriter, writing several number one hits. paulgordonmusic.com

You can also find Streaming Musicals on Facebook and Instagram.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Re-Reading Sense and Sensibility,” is by Sandra Barry.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 20, 2024

A Song Can Sing So Much, by Lori Mulligan Davis

Most people experience a midlife crisis, oh, in their forties? sixties? I had mine at 22, realizing I’d aged past my favorite heroines. My summer studying Shakespeare at Oxford, travel through Britain, and grad school at William and Mary were behind me. The rest of my life would be marking time. I didn’t know 22 wasn’t an age, but a year. In 2022, I was asked to be plenary speaker at my favorite Austen conference and the dramaturg for an Austen play. And not just any play! Harper College’s production of Paul Gordon’s Sense and Sensibility, a musical whose premiere I’d loved so much at Chicago Shakespeare Theater, I’d flown to San Diego to see their Old Globe remount “just one more time.”

I’m glad to say now you and I can watch the Chicago Shakespeare production anytime we choose, on the Streaming Musicals website. Whew!

(From Sarah: This is the nineteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I care, because when well done, an Austen adaptation becomes an immersive experience. My guess is Paul Gordon achieved this by approaching the show as a respectful collaboration with Jane Austen, even though by then she’d been below Winchester Cathedral for 198 years.

By adding song, Gordon neatly fits the emotional power of thirteen reading hours into an hourglass. With a skill rivaling that of the great Alan Jay Lerner, Gordon mines phrases from Sense and Sensibility that transform Elinor’s and Marianne’s grief and despair, John’s and Fanny’s greed, Sir John’s and Mrs. Jennings’s active kindness, Marianne’s flights of feeling, Marianne’s and Willoughby’s infatuation, Brandon’s longing and forbearance, Lucy’s (grammatically incorrect) crowing, Elinor’s and Edward’s resolve, Elinor’s forgiveness and release from pent-up silence, and the marrying couples’ ultimate joy into satisfying song. I alerted Chicago Shakespeare that the soundtrack needs a warning label: “Do Not Play While Driving.” I can’t help but applaud each song, even in Chicago traffic.

Here’s one to applaud: Colonel Brandon sings “Lydia,” the words a steady burst of emotion over the circumstances that devastated his life and the life of his lost beloved. It’s well worth a listen! In the streaming video, currently free, it begins at 29:14.

“Lydia” is Gordon’s name for Eliza in the novel, possibly renamed to avoid confusion with her daughter. In Austen’s day (and novels) firstborn boys or girls were often named for fathers or mothers. With neither Eliza appearing on stage, different names help the audience.

“I Hear Your Hollowed Voice”

“Each and every day,” Colonel Brandon relives Lydia’s final breath-starved farewell. The now-treatable tuberculosis was called consumption when it ravaged the 17th through 19th centuries, causing 25% of all deaths in Europe during that period and perhaps causing or contributing to Austen’s death (Brenda S. Cox, “What Killed Jane Austen?” [2021]). We now know people can safely harbor the TB bacteria (as Latent TB) inside their bodies as long as their immune system remains healthy. But if the immune system becomes compromised, Inactive TB can become Active TB weeks or even years after initial infection. Highly contagious, TB is spread by coughing, speaking, and singing. Because it can lie inactive for so long, it first was mistaken as hereditary rather than contagious. Did it orphan Lydia/Eliza? Fleeing her abusive marriage without a financial safety net, she was forced by hunger and homelessness into the poorhouse. Extreme conditions or close quarters exposed her to tuberculosis or taxed her ability to fight Latent TB. The abuses of her uncle and husband led to her death.

We were cursed right from the start

Between my father’s greed

My brother’s wrath

My misbegotten place in life.

Colonel Brandon’s father, Mr. Brandon, has a shot at being the most despicable offstage character in all of Austen.

Mr. Brandon was the trustee of his niece Lydia’s considerable fortune. As her guardian, he’d been entrusted to arrange her marriage settlements, a contract to protect her and her children. But feeling the pressure of his own debts, Mr. Brandon drafted a marriage contract solely in the groom’s favor—the loveless son he forced Lydia to marry. In the play we hear Brandon telling Elinor the story:

BRANDON

We had grown up together and loved each other from the time I can remember. But my father persuaded my elder brother to marry her. Lydia’s fortune was large and my family’s estate much encumbered.

ELINOR

From father to son. I will never cease to be surprised how easily men favor fortune over love. Was your brother at least attached to her?

BRANDON

No, he had no regard for her at all. She experienced great unhappiness. Divorce and ruin followed. I was overseas with my regiment when she was seduced by the first man to show her any kindness. By the time I could return home I found my Lydia dying of consumption, her two-year-old child by her side.

Colonel Brandon laments “antiquated customs / we’ve quite outgrown.” Those customs played into the hands of the unscrupulous Mr. Brandon, and “family is disregarded / cast out and thrown away / by senseless inconsistent laws / we still obey.” Because a wife could not own separate property (based on the husband-favoring Law of Coverture), a careful father of the bride would use the workaround of marriage settlements, legally binding financial contracts in which parents of the bride and the groom entrusted land and assets to trustees at the time of the marriage. Trustees became the legal owners of the assets, while the bride and bridegroom held beneficial ownership during life that transferred at death to “the fruit of their union” (a child or children). A bride’s father made sure the property was owned by trustees who could best protect the daughter’s and grandchildren’s interests, sometimes even if the marriage ended in divorce.

In this way, the father made sure the enticing dowry that had ensured his daughter’s marriageability would benefit her during the marriage and give her a widow’s jointure (housing bequeathed to her, specific possessions and jewelry, yearly allowance, child support for minors, etc.) if her husband died first. The contract also made sure the groom’s father would commit financially to the marriage and grandchildren. Wives in Regency England had few individual rights. The foresight of prenuptial agreements offered protection. The Lydia Bennets who decided to elope faced a lifetime without safeguards. So did someone who had Mr. Brandon negotiating both sides of the agreement.

To learn more, read Regina Jeffers’ clear explanation of marriage settlements; Mr. Brandon’s gross negligence as Lydia’s representative; and Lydia’s vulnerability under the law, as a woman, an orphan, and a minor (“Negotiating Marriage Settlements During the Regency Era” [2023]).

Colonel Brandon calls his place in life “misbegotten,” not as in “out of wedlock,” but “completely lacking in value; worthless; inspiring pity.” By law or custom, primogeniture dictated a father’s entire or primary estate be settled on the firstborn (usually a son). Entailed property was bound by legal requirements over generations. All other children had to make their own way, sometimes helped by money protected externally by the mother’s marriage settlements. In Regency England, this relegated younger sons to “the genteel occupations” (the clergy, armed forces, or law) and the daughters to the Marriage Mart.

Despite the fact that Colonel Brandon is in love with the young lady whose fortune could save the family estate, Lydia is forced to marry his brother—its heir. Colonel Brandon has joined the army, and with heroic sacrifice (which should earn him Dashing Hero Points with Marianne Dashwood), he procured an exchange to an overseas regiment to give Lydia the greatest chance to forget him. Brandon chose never to forget, but to recall her voice and face “each and every day,” long after her death. Yet, as time begins to blur the lines, another “accidental miracle” occurs in the person of Marianne Dashwood.

But Lydia there’s someone who

reminds me of you

Lydia . . .

With poetic rightness, Brandon’s lament ends with a dot-dot-dot. And the despairing lover who says “miracles are fleeting” and “life is random circumstance” tells his “departed, cherished friend” of “someone who / reminds me of you.” Marianne Dashwood shares Lydia’s “same warmth of heart, the same eagerness of fancy.” While some readers feel Marianne merely settles for the flannel-cocooned gent who aides the family, viewers of Paul Gordon’s musical applaud her choice. We’ve overheard Colonel Brandon’s heart and we hear her smile as Marianne sings, “In a moment, / There’s a sudden burst / where I finally see what I missed at first. / And the things I felt now appear reversed.”

As Marianne first sang in Act One, “Love’s a wonder.” Indeed.

Watch the musical: You can view Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s production of Paul Gordon’s musical Sense and Sensibility for free for a limited time on the Streaming Musicals website, as well as rent or buy the video via Vimeo or Amazon.

Words, words, words. That pretty much sums up Lori Mulligan Davis. A reader, writer, freelance editor, and book coach, Lori’s sure that a favorite project will ever be Brenda Cox’s Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. Though Lori has been a magazine managing editor, curriculum writer, academic-press editor, online theater reviewer, and museum educator at the Naper Settlement, this blog post proves that the Zenith of her life was speaking at the 2022 Jane Austen Summer Program on “‘I Was Quiet, But I Was Not Blind’: Sight and Silence in King Lear and Mansfield Park” and being Professor Kevin Long’s dramaturg for his production of the Paul Gordon musical Sense and Sensibility at Harper College. A former publicity director of JASNA-Greater Chicago Region, she’s current president of the Chicago region of American Christian Fiction Writers and enjoys leading writing workshops for professional writers, educators, and teens. Lori contributed the photos. She says zinnias are her favourite flower “because they seem like a bouquet within a single flower.”

Lori describes this as her “Jubilant arrival at The Old Globe Theatre, San Diego, to see Sense and Sensibility ‘one more time.’”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “Writing the Musical: Sense and Sensibility,” is by Paul Gordon.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 16, 2024

Of Sandwiches and Obligations, by Shawna Lemay

We live in a time where our empathy muscles are atrophying, our ability to navigate moral and ethical concerns seems wanting in many. Myriad studies point to fiction as the most efficacious way for humans to develop empathy and refine our critical faculties. Fiction allows us to think things through, often before we encounter similar experiences in our own lives.

(From Sarah: This is the eighteenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I have thought about the famous Chapter 2 of Sense and Sensibility in so many situations since reading it eons ago. The comedic timing which rapidly takes us from the resolution of John, the half-brother, giving his sisters a thousand pounds after the death of their father, to, on the advice of his wife, figuring that any gift would be “absolutely unnecessary, if not highly indecorous.”

It’s a shocking delight to trace the path whereupon John’s wife talks him down from a thousand pounds, to 500, to some unsettled amount “occasionally,” to “a present of fifty pounds now and then” to “sending them presents of fish and game, and so forth, whenever they are in season.”

Beautifully daft and absurd when in the midst of the conversation he says, “One had rather, on such occasions, do too much than too little.” And in the end, he congratulates himself on his kindness. One cannot over-praise Austen in the construction of these scenes.

One day a few weeks ago I had a shift in the inner-city library during which I interacted with houseless folks, new immigrants, among others. I’d helped some folks who were in such a bad way that they were crying, and I had some small part in sorting them out. It felt useful but also just way too insignificant. I began the walk to my car which was a ways off so I could get my parking for free. It was a fairly rough shift, honestly, as many of them will be and it’s nothing new to me—I’ve worked with this population for going on fifteen years. I was congratulating myself on the free parking as I walked, hoping my car hadn’t been ransacked, as had happened before. I was hoping I could catch a break, really, as one does. I was cutting through back alleys, and side streets. My legs were tired, and my feet hurt from being on them for six hours. All fine. It’s a blessed life and I know it, most days.

I walked by a bunch of folks perching on a cement step and they called out to me. They looked familiar. Maybe I’d seen them in the library earlier. I just wanted to get to my car several blocks away still. They wanted cash. And who carries cash these days? I called back, sorry I don’t have cash. Kept walking. Are you sure? I’m sure. Sorry. Kept walking. Can you buy us a sandwich? Kept walking. Two more steps. I stopped. Because why not? Why not? I really wanted to get home. But why not?

I look around and right there, beautiful coincidence, a convenience store. I take the one fellow with me, and he tells me his name, which I recognize. We’ve met before. At the beginning of the pandemic, I had met him on one of my very early morning city photography outings and his nickname is distinctive. Those mornings were eerie—I would usually have the downtown streets to myself along with a few houseless folks who were invariably friendly.

It’s always the hands that get me, the dirt that would take days to lift out and long soaks. I took him into the store and bought him a sandwich and a ginger ale and one for his friend, too. He wanted his heated. I got it heated. We went out. His friend thanked me, we all chatted a bit, and I carried on.

When I got to my car, I had the thought: that actually felt like the best part of the day. And it wasn’t a big deal. I’ve bought countless burgers and sandwiches and coffees for houseless folks over the years and sometimes I’ve given cash and let people have the dignity of buying their own chips and pop. It’s something they often say you shouldn’t do. I wouldn’t usually talk about this because it sounds like virtue signalling even to my ear. But you know, to heck with that. Because some days I don’t know how to get on in the world with all its misery and sorrow. And giving someone a pair of warm socks or some French fries from Dairy Queen or whathaveyou, it helps me probably more than them. I know that.

But whenever I do this, I always think about Jane Austen and Chapter 2 of Sense and Sensibility. And that piece of work, John, and his wife, an even bigger piece of work. And how if things had been just a bit different, he’d have talked himself into giving the Dashwoods some cash, and helped them find somewhere decent to live, rather than making them homeless for that bit anyway. I mean, the story would have ended right there then if he’d been a mensch.

Luckily, we see how it plays out. John is unforgiveable for always and ever. But. We are rolling down a new path.

Rumi, the 13th century Sufi mystic, said in a poem:

Don’t grieve for what doesn’t come.

Some things that don’t happen

keep disasters from happening.

In the same poem, the definition of Sufism is given as, “The feeling of joy / when sudden disappointment comes.”

And there is disappointment following the abdication of help for the Dashwood sisters and mother by their half-brother, John. But certainly, the joy is deferred until the end of the book. We won’t dwell on what would have happened if in an alternate Jane Austen reality, the Dashwoods had been treated benevolently by their brother.

Do we these days think about our obligations to one another? Perhaps not as often as we ought. In her book On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World, Danya Ruttenberg quotes an international law scholar, Louis Henken. He says that our society “focuses on rights afforded to the individual, rather than on obligations to one another. . . .”

In Lauren Berlant’s On the Inconvenience of Other People, they say that “just by existing, historically subordinated populations are deemed inconvenient to the privileged who made them so. . . .” And the sudden shift of worth and class by the Dashwoods makes them inconvenient. They have no legal rights to any money or land, and John, as we see, is easily talked down the stairs of obligation.

As the Dashwoods approach Barton Cottage, their new reduced residence, they go from “melancholy” and “dejection” to a cheerfulness in their approach. The view is of a “pleasant fertile spot, well wooded, and rich in pasture. After winding along it for more than a mile, they reached their own house” (Volume 1, Chapter 6).

In his book on contingency and Buddhist thoughts on good and evil, Stephen Batchelor talks about paths. We create a path by carving it out and “it entails both doing something and allowing something to happen. A path is both a task and a gift.”

The Dashwood sisters and Mrs. Dashwood have a new path thrust upon them. They are thrown into contingency, “if not this, then that.” And of course, their new task becomes, eventually, a gift. Their new happiness, one feels, isn’t entirely contingent on the happily ever afters that Marianne and Elinor find with Colonel Brandon and Edward Ferrars.

They have been treated without any sense of true obligation or goodness, but they have not dwelt on what is owed them but on what is. Which brings me to that beloved poem by Galway Kinnell, “Prayer,” which goes:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

And I think that whatever might have happened along the path for Elinor and Marianne, if that had happened rather than this, well—this reader feels they would have been equal to it. They would have found some measure of joy, regardless. As luck would have it, they were helped by another connection, by relations, so their homelessness was short-lived.

Still, Austen gives us a lot to think about in terms of our obligations to one another. How easily we may be talked out of them, and what a loss to us all when we are.

Quotations are from the Oxford 3rd edition from the illustrated series The Novels of Jane Austen, edited by R.W. Chapman.

Shawna Lemay is the author of Apples on a Windowsill and other books, including the novel Everything Affects Everyone, which I wrote about here last year in a post called “Secrets that everyone knows.” She wrote “The Sponge-Cake Model of Friendship” for All Lit-Up and so, she says, it seems appropriate to follow this up (several years later) with a piece referencing sandwiches. Author photo by Robert Lemay. Sandwich photos by Shawna.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future guest posts in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” The next post, “A Song Can Sing So Much,” is by Lori Mulligan Davis.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

Sense and Sensibility and Sewing, by Marilyn Smulders

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.

August 13, 2024

On Sense and Sensibility and Lady Susan, by Anne Giardini

A strange thing happened when I opened up my old (Bantam Classics edition, January 1983) copy of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility last month. The biography of Austen inside the front cover lists Austen’s works, among them the epistolary novel Lady Susan, which is, famously, about a terrible mother. Immediately, I set Sense and Sensibility aside and picked up Lady Susan.

I so readily exchanged the confections of Sense and Sensibility for the talons of Lady Susan because another famously terrible mother, a real world one, Alice Munro, was in the news on the day I picked up Sense and Sensibility. Alice Munro, who won a Nobel Prize for literature in 2013 and who died in May of this year, was a friend of and exemplar to my mother, the writer Carol Shields, who died twenty-one years ago. My mother admired Munro’s work, as we all did, my mother, my three sisters and I. We referred to her reverentially whenever her name came up, as did others, as The Divine Alice. Now, in July 2024, Munro had been exposed to the world as having abetted and concealed sexual offences committed by Munro’s second husband, Gerald Fremlin, against her youngest daughter, Andrea, when Andrea was nine years old, and likely for a period before and after that. Faced with evidence that Fremlin had abused Andrea Munro, including Fremlin’s written admissions, Munro failed repeatedly to protect or support her daughter. Munro instead clung to her marriage to Fremlin, and even tried to shift to Andrea a portion of the blame for Fremlin’s crimes. Andrea was effectively silenced, expelled from the family, and failed over and over by adults around her who conspired to keep matters quiet. Except, that is, for a quickly dispatched criminal trial; Fremlin pled guilty; he was given a nominal sentence; everyone went on as before. Andrea did not make her situation widely known until two months after her mother’s death.

(From Sarah: This is the seventeenth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will continue through to the end of the summer. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

I was certain I had read Lady Susan before. It is after all included in a collection of Austen’s juvenilia that I have on my bookshelves. But I had forgotten almost everything except the first chapter/letter, in which Lady Susan claims that she is going to pay her neglected daughter Frederica greater attention—by sending Frederica to a private school. This is an early, but not the first, hint in the book that Lady Susan’s stated and actual intentions do not align with each other or with what might be expected of a good mother.

The book, which was written when Austen was still in her teens, is short and tightly plotted. I finished it in one sitting, caught up in a drama in which Lady Susan is the cat and her daughter, poor, silenced, dejected, terrified, artless Frederica, is a trapped mouse left to her mother’s sharp-clawed mercies.

Bad mothers are at the centre of some of our oldest and most memorable stories. Eve raised her children in dust and pain instead of in paradise. Herodias had her daughter Salome command the head of John the Baptist. A mother, unnamed, agreed that Solomon should cut an infant into pieces. Medea slaughtered her sons. Queen Gertrude married, in haste, her husband’s murderer. Charlotte failed to protect Lolita from the predations of Humbert Humbert.

There are perfect mothers in fiction and in art as well. The saintly depictions by Dickens and Mary Cassatt come to mind. These mothers suffer from the problem of not being interesting or believable.

Normal, that is to say, inadequate, mothers are far more common, and in fact are often used by Austen as comic foils. Consider how Mrs. Bennet’s avidity to marry off her daughters in Pride and Prejudice exposes her to ridicule and disdain. Or Lady Bertram mindlessly doting on her pug in Mansfield Park.

I returned at last to Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen’s first published novel (1811), although likely her second- or third-written, to find it too makes good use of the idea of the inadequate mother, and often to comedic ends. Mothers are meant to have good sense. Mrs. Dashwood lacks good judgment and Charlotte Palmer is giddy and oblivious. Mothers are meant to be warm and loving. Fanny Dashwood, Lady Middleton and Mrs. Ferrars are lacking in affection. Mothers are meant to love all their children equally. Mrs. Jennings, Mrs. Dashwood and Mrs. Ferrars all favour their second, almost inarguably less-deserving child.

In the wake of the revelations about Munro, and the extravagant bad behaviour in the pages of Lady Susan, I found it challenging to focus on the milder failures of maternity in Sense and Sensibility. Sense and Sensibility is a comedy that ends adequately. Lady Susan is a tragedy, even if it ends well for the tender and stalwart Frederica. I reread Lady Susan, looking for and finding parallels between Frederica and Lady Susan on the one hand, and Andrea and Alice Munro on the other. As a mother, Lady Susan deprives Frederica of comfort, company, security and support. She maintains a dalliance with, and eventually marries, Sir James Martin, while at the same time trying to force Frederica, who is sixteen years old, to marry him. She is self-absorbed and secretive. She betrays her daughter’s confidences. She lies about her daughter to others. Alice Munro’s offences were real, more current, and measures worse.

Austen said of Sense and Sensibility, in a letter to her sister Cassandra dated April 25, 1811, “I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child.”

Mothers can and do forget their children. Munro left her children behind with her first husband, Jim Munro, when Andrea was about six years old. After that, Andrea saw her mother mainly during summer holidays, time during which she strove and often failed to elicit maternal affection from her mother. Time during which crimes were committed against her.

It is impossible to know at this reach of time what Austen thought of her mother but I find it impossible to believe that their relationship was wholly satisfactory. Whatever Jane Austen thought of her own mother, her novels evidence close attention to the styles and manners of mothers in her own time, and it is a truth universally acknowledged that Austen’s writerly lens works as well in our time as in hers. As such, the novels of Jane Austen, including Lady Susan and Sense and Sensibility, provide a system for examining mothers today. My own mother reflected the good sense and equilibrium of Mrs. Weston in Emma. Yours might be more like Lady Catherine de Bourgh, in which case, may God help you. Andrea Munro drew Lady Susan.

So what is the literary chatter about Munro, who was never, after all, known to have been an excellent mother? I’ve had dozens of exchanges with friends and writers and lovers of Munro’s work (three sets that heavily overlap). Several have pointed out that it is reductive to treat these revelations as the one and only framing for Munro. To do so would be not only banal but also a denial of creativity and complexity. Others have pointed to ways in which secretiveness, blame, self-interest, and the shirking of moral responsibility are the source of so many of Munro’s stories.

There is also the fact that the bad mother is a Janus-faced trope since the attributes that subject a mother to charges that she is unfit—independence of thought, ego, ambition and the like—are also aspects of a wholly-realized self. It isn’t marriage that leads a woman to cut off her heels or toes, as Cinderella’s sisters did to try to fit into that glass (or fur) slipper, but childbirth. A good mother is expected to be selfless and abnegating. She must put her children’s interests ahead of her own. Shel Silverstein’s book, for example, The Giving Tree, is a horror story—for the tree/mother. If a “good mother” has an inner life and thoughts and desires of her own, they are expected to be set aside, or at least buried deep enough to cause no breaking of the glassy maternal and marital surface.

Munro’s work extends the margins of what we can expect of even the very best writers. She created unique and enduring worlds. It is also the case that much of her work came from the wellspring of sexual interest between men and women, and how its pursuit can drive women, and men, to behave badly. It may be the case that her kind of genius can lead to or involve or come out of hubris. None of this is an absolution or even any kind of explanation. There is no single or conclusive key to Munro’s work or life.