Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 11

May 10, 2024

“A rather doubtful experiment” (#ReadingKilmeny)

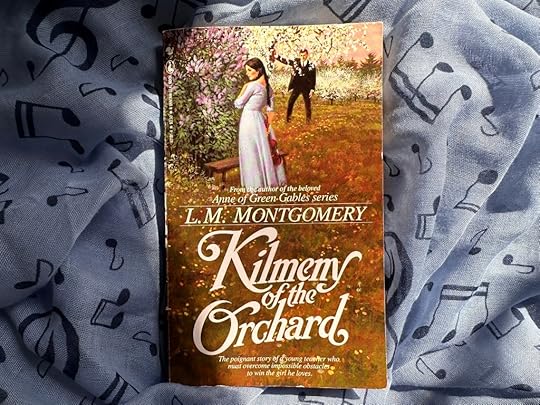

L.M. Montgomery’s third novel, Kilmeny of the Orchard, was published in 1910, following the phenomenal success of Anne of Green Gables in 1908 and Anne of Avonlea in 1909. Her publisher, L.C. Page, expected her “to produce one book after another at breakneck speed,” Mary Henley Rubio writes in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Although she would revisit—not always willingly—the world of Anne Shirley many times in the coming years, for this third book, Montgomery expanded a short story she had published between December 1908 and April 1909 in a magazine called The Housekeeper, a romance called “Una of the Garden.” Her hero, Eric Marshall, falls in love with a beautiful and talented violinist, Kilmeny Gordon, who plays pieces of her own composition in an old orchard not far from the house where Eric is boarding while he teaches at the local school in Lindsay, Prince Edward Island.

Please join my friend Naomi MacKinnon and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here. I’ll be back later this month with another post on the novel.

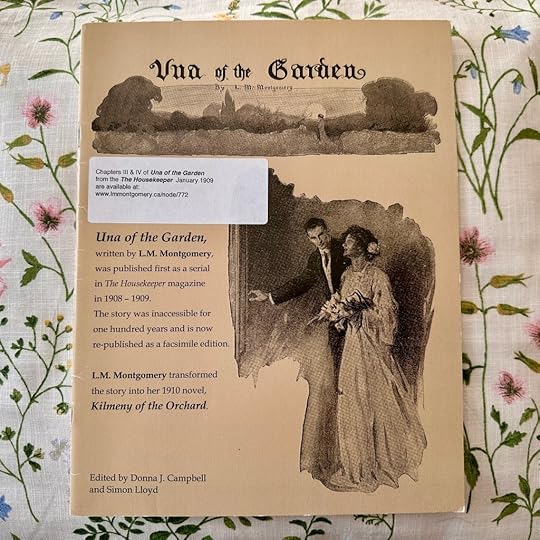

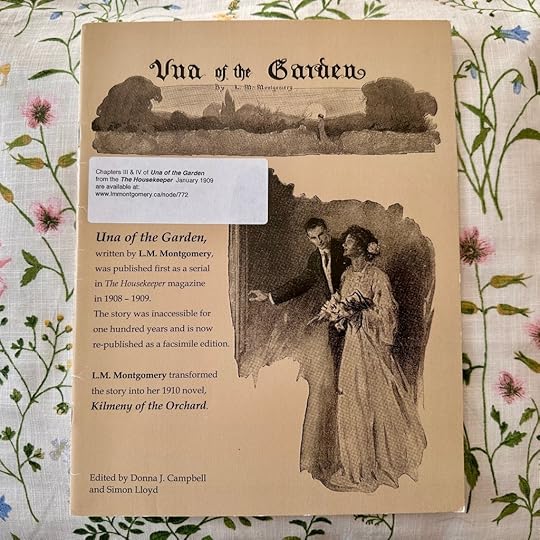

On a trip to PEI several years ago, I bought a facsimile edition of “Una of the Garden,” in which L.M. Montgomery is described more than once as “Author of Ann of Green Gables.” (No “e”! Unforgivable.) Her story appears alongside advertisements for Snider Pork & Beans (“People who can’t eat ordinary, indigestible, home-cooked Pork and Beans enjoy Snider’s”), Heatherbloom Taffeta Petticoats (“made in all the shades and stripes so modish to-day”), and Jell-O (“best for the whole family because it is delicious, pure, wholesome and nutritious”). When she revised and expanded the story, Montgomery changed the names of characters and places, including Una Marshall, now Kilmeny Gordon, and Eric Murray, now Eric Marshall. Neil Marshall, the orphaned son of “a couple of Italian pack-peddlers” who becomes Eric’s rival for the heroine’s affections, is renamed Neil Gordon. The setting is changed from Stillwater to Lindsay, and the garden is replaced by an orchard.

Montgomery was not happy about her publisher’s demands. Her original story was not long enough to please Page, “so I have had to re-write and lengthen it—a business I dislike very much,” she wrote in her diary in December 1909 (The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston). She had been working, she said, “until I would fairly feel faint with fatigue,” and she was afraid of the “terrible attacks of gloom and restlessness” that often tormented her. “If I can only keep physically well and nervously unbroken I shall not mind anything else so much.” Although Montgomery was tired, Rubio says that working on the novel served as a distraction, as she found that “writing could often help her block out worries in her real life. It was a pleasant way to escape.”

Montgomery wrote of Kilmeny that “It is a love story with a psychological interest—very different from my other books and so a rather doubtful experiment with a public who expects a certain style from an author and rather resents having anything else offered it.” Already she was facing the challenges of writing for an audience that was hungry for more Anne stories, and more books with a pastoral island setting.

In her new novel, she made PEI even more idyllic than in her first two “Anne” books. As Eric’s friend Larry West says in a letter when he is trying to persuade Eric to take his place as teacher in Lindsay for the last few weeks of the school year, “Prince Edward Island in the month of June is such a thing as you don’t often see except in happy dreams. There are some trout in the pond and you’ll always find an old salt at the harbour ready and willing to take you out cod-fishing or lobstering” (Chapter 2). The orchard, especially, is perfection:

Most of the orchard was grown over lushly with grass; but at the end where Eric stood there was a square, treeless place which had evidently once served as a homestead garden. Old paths were still visible, bordered by stones and large pebbles. There were two clumps of lilac trees; one blossoming in royal purple, the other in white. Between them was a bed ablow with the starry spikes of June lilies. Their penetrating, haunting fragrance distilled on the dewy air in every soft puff of wind. Along the fence rosebushes grew, but it was as yet too early in the season for roses. (Chapter 5)

As Elizabeth Rollins Epperly writes in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance, “Montgomery makes the story pleasing to read and lifts it briefly beyond formula with her loving descriptions of sunset and garden.” Many of the passages about the setting are lovely, but sometimes I found them excessive. For example, “most of the idyllic hours of Eric’s wooing were spent in the old orchard; the garden end of it was now a wilderness of roses—roses red as the heart of a sunset, roses pink as the early flush of dawn, roses full blown, and roses in buds that were sweeter than anything on earth except Kilmeny’s face.”

Kilmeny is beautiful—there’s no doubt about that in this novel. She herself doesn’t know it, however, because her mother broke all the mirrors in the house and did not allow Kilmeny to see her own face. Kilmeny has never been able to speak, and the cause of her disability is mysterious. Is she physically incapable of speaking, or has her fate somehow been shaped by her mother’s “sin” (as her Aunt Janet Gordon believes), or is there some other reason she lacks a voice? Elizabeth Waterston says in Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery that “the ‘psychological interest’ comes from the doctor’s theory of psychosomatic impairment caused by ‘trauma’ and his hope that Kilmeny may be shocked into a cure.”

I’ll write more next time about Kilmeny’s inability to speak. For now, I want to ask what you think of Kilmeny, Eric, and Neil, the descriptions of the landscape, and Montgomery’s “experiment” in this novel. Did you find Kilmeny formulaic, as many reviewers and critics have suggested? “For the first time,” Liz Rosenberg writes in House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery, “Maud’s work received negative reviews. One reviewer called it ‘a terrible specimen of the American novel of sentiment.’ Another said that the main character was enough to bring on ‘a bilious headache.’” Epperly says that “Everything in the novel belongs to formula,” including the character of Neil Gordon, the “dark, passionate, unscrupulous foreigner (Montgomery’s story makes unblushing use of xenophobia and bigotry).”

As I was reading the novel, for the first time since I was about ten or eleven, it occurred to me that while I found it engaging—and often disturbing—I probably wouldn’t have picked it up at all if it had been written by someone other than Montgomery. I wouldn’t say it gave me a bilious headache, but it isn’t my new favourite Montgomery novel, either. Even so, I’m finding it interesting to learn about how Kilmeny fits (or doesn’t fit) with Montgomery’s other novels, and where the novel falls in the development of her career. I wanted to reread this novel precisely because it doesn’t receive as much attention as the Anne and Emily books. And I was curious about the way Montgomery transformed “Una” into Kilmeny.

I came across this list of LMM books in my childhood library recently. I didn’t own Kilmeny of the Orchard (until I bought a copy a couple of months ago), and when I read it as a child, I must have borrowed it from the library. While I was sorting through notebooks and papers from elementary school, I also found this drawing of a bookshelf.

I’m keen to hear what you think—in the comments on this post, or on social media (Facebook; Instagram), or on your own blog—and I’ll look forward to continuing the conversation next week. Thanks for reading with us!

From Bookish Beck:

Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

“I found this fairly twee, with an unfortunate focus on beauty (‘“Kilmeny’s mouth is like a love-song made incarnate in sweet flesh,” said Eric enthusiastically’), and marriage as the goal of life. But it was still a pleasant read, especially for the descriptions of a Canadian spring.”

More photos of spring in Kent, sent by my friends Sheila and Hugh Kindred:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

May 3, 2024

“The murmur that rings for ever” (#ReadingKilmeny)

I’m looking forward to discussing L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard with you this month. My title for today’s post comes from the third chapter of the novel, in which the hero, Eric Marshall, has arrived in Lindsay, Prince Edward Island, to fill in for his friend Larry West as a teacher for the last week of May and all of June. Eric takes note of “distant hills and wooded uplands,” which are “tremulous and aerial in delicate spring-time gauzes of pearl and purple”; of “young, green-leafed maples” and “emerald fields basking in sunshine”; and of the “calm ocean,” which “slept bluely, and sighed in its sleep, with the murmur that rings for ever in the ear of those whose good fortune it is to have been born within the sound of it.”

When I was in PEI two weeks ago, the trees and fields weren’t yet green, but the ocean was calm. I took pictures of the water and dunes at Brackley Beach, along with pictures of trees and spring flowers and the sunset as seen from the window of my hotel room in Charlottetown.

St. Dunstan’s Cathedral, Charlottetown, PEI

Please join my friend Naomi MacKinnon and me this month as we read/reread Kilmeny of the Orchard. You can find the invitation to the readalong here.

I’ll have more to say next week about the publication of Kilmeny. Today, I want to share with you some more photos of spring, sent to me by my friends Sandra Barry and Sheila and Hugh Kindred. Sandra sent photos of Eastern Painted Turtles and wintergreen blooms, taken by her sister Brenda Barry in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. Sheila and Hugh sent photos of apple blossoms, cowslips, and bluebells in Kent, England.

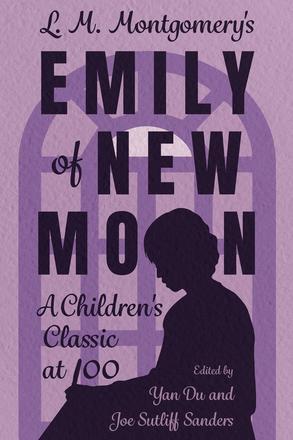

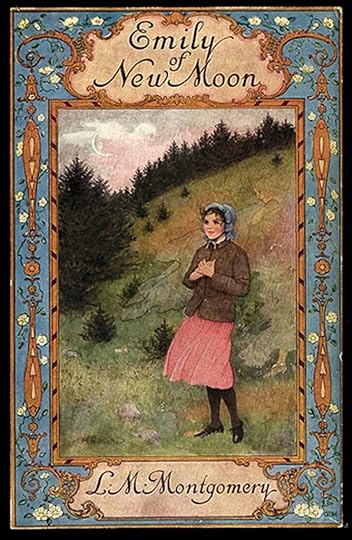

I also want to draw attention to a new book that was published last month: L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon: A Children’s Classic at 100, edited by Yan Du and Joe Sutliff Sanders, and published by the University Press of Mississippi. In the three “Emily” books, Montgomery “turned from Anne and plunged into more intricate aspects of gender, adolescence, nature, and authorship,” and this book is “the first scholarly volume exclusively dedicated to the trilogy.” One of the contributors to the book, Lesley D. Clement, is writing a guest post for my blog series this fall, “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150.”

More spring highlights:

My friend Meghan Marentette launched her debut picture book last Sunday at Woozles, one of my favourite bookstores. The book is called Rumie Goes Rafting, and features Rumie and Uncle Hawthorne in a forest setting where “The scent of dew filled the air, and the moss squished underfoot.” To Rumie, “Everything smelled like fresh adventure.” Meghan created the characters and all the props in this beautiful book, and photographed all the scenes in the woods near her home. She’s already working on a sequel, set in winter. If you’re interested, you can follow the complex and fascinating process of creating these books on Meghan’s Instagram.

Rumie in my back yard

Here’s a spring bouquet from my friend Kathy Cawsey, who wrote a guest post on Jane of Lantern Hill last May and is writing a guest post this year for my Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility:

I’ve been listening to The Blue Chapter of Project Earth, music composed by jazz pianist Florian Hoefner, featuring poetry by Don McKay and performed by the Iris Trio. Christine Carter, the Iris Trio clarinetist, was interviewed in this CBC article. The goal of Project Earth is to help “illuminate the impact of human behaviour on the environment … while also giving centre stage to the immense beauty and wonder found in nature.” Christine (whom I met last fall at Woozles) says that the project is “intimately connected” with the province of Newfoundland, where she lives with her family. “The arts can help people get their hearts involved,” she says, “so that we care about the numbers and want to make a difference.” The two other members of the trio are Anna Petrova, who lives in Louisville, Kentucky, and violinist Zoë Martin-Doike, who lives in New York City. I’m already looking forward to the Iris Trio’s Green Chapter of Project Earth: music by Sarah Slean and Andrew Downing, with poetry by Karen Solie.

One last note for today’s “scrapbook” post: have you read about Rabbit Hole, a new museum of children’s literature in North Kansas City, Missouri? I’d love to visit someday, and in the meantime, I enjoyed reading about exhibits that recreate scenes from beloved picture books such as Bread and Jam for Francis and Blueberries for Sal.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“A green solitude of wavering light and shadow” (photos of L.M. Montgomery’s grave in the Cavendish Cemetery, on the 82nd anniversary of her death)

Let’s read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

More photos from Sheila and Hugh:

April 24, 2024

“A green solitude of wavering light and shadow”

In The Story Girl, L.M. Montgomery writes of the cemetery “where our kindred of four generations slept in a green solitude of wavering light and shadow” (Chapter 5). Here’s the cemetery where Montgomery herself and many of her relatives are buried:

These photos are from a summer trip a couple of years ago, when there was plenty of green in the cemetery. I spent last weekend in Charlottetown, PEI, and I stopped in Cavendish on the way there to take more photos. I was the only visitor at that moment. Plenty of solitude; not as much green, yet.

Montgomery died eighty-two years ago today, on April 24, 1942, and she was buried here five days later. Liz Rosenberg writes in House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery that “The local outpouring of grief was immense. The little white church filled to overflowing. Mourners spilled out of the church and onto the grounds. The Cavendish school closed for the afternoon; grieving schoolchildren came running over. One girl remembered telling her mother, ‘I have read all her books and I know her.’”

More photos from last weekend: New London, L.M. Montgomery’s birthplace museum, and the National Park in Cavendish.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Let’s Read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

March 22, 2024

Let’s read Kilmeny of the Orchard in May (#ReadingKilmeny)

Please join my friend Naomi and me to read L.M. Montgomery’s Kilmeny of the Orchard in May. I thought I’d send out the invitation now to make sure anyone who wants to join us has time to read or reread the novel. Feel free to join the conversations in the comments on Naomi’s blog or mine, and if you write your own post about Kilmeny, please let us know.

I’m also planning to have a look at Montgomery’s story “Una of the Garden,” which she transformed into Kilmeny of the Orchard.

Here’s how Montgomery describes Eric Marshall’s discovery of the orchard (in the novel):

The charm of the place took sudden possession of Eric as nothing had ever done before. He was not given to romantic fancies; but the orchard laid hold of him subtly and drew him to itself, and he was never to be quite his own man again. He went into it over one of the broken panels of fence, and so, unknowing, went forward to meet all that life held for him.

I’m curious to read more, as I don’t remember the book very well at all. I think I was ten or eleven the last time I read it.

It’s spring in Nova Scotia and I was delighted to find crocuses in the back yard of our new house. In a recent essay, Margaret Renkl writes that “It’s been a dark winter of worries, but the wildflowers are blooming and the birds are singing again. It feels like coming home.” She says her “happiness is twofold. Spring is here! But also: Thank God it didn’t come too terribly early this year.”

(The snowdrops are from my mother’s garden. I took the picture of crocuses on a neighbourhood walk. Our crocuses are lovely, and this same shade of pale purple, but they’re more scattered through the muddy back yard and thus a little less photogenic.)

This year, the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies is sharing tributes to Montgomery from people around the world in honour of her 150th birthday (#Maud150). The editors recently posted three tributes on the theme of Spring Awakening, including one from Ukraine. Olga and Kateryna Nikolenko write that “For us here in Ukraine, L.M. Montgomery’s works hold a special significance throughout the times of war. A short while ago, Anne of Green Gables was introduced into the World Literature curriculum to read in the seventh and tenth grades—and now, Anne teaches Ukrainian students resilience, compassion, and optimism.” You can read the rest of the tribute here.

Here are a few other things I’d like to share with you:

Sheila Johnson Kindred has written a wonderful tribute to our dear friend Patrick Stokes, who died on Christmas Day, 2023.

Remembering Patrick Stokes, Admiral Charles Austen’s great great grandson

Sheila writes of the many conferences Patrick organized, including two here in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2005 and 2017; of his keynote lecture at the JASNA AGM in Montreal in 2014; of his performance as the Prince Regent in Syrie James’s play “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park”; of the term he served as Chair of the Jane Austen Society, and of the assistance he offered when Sheila was writing her biography of Fanny Palmer Austen, Charles’s first wife.

I can still picture Patrick at the various Austen-related sites in the Halifax area that we visited during the 2005 and 2017 conferences, including Admiralty House; Government House, where Charles and Fanny Austen danced at a ball that Fanny described as “splendid”; and St. Paul’s Church, where their daughter Cassy was baptized in October 1809.

I met Patrick on the first day of the 2005 conference. He had invited me to be one of the speakers, and I was delighted to return home to Halifax from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I was living at the time. Somehow, Patrick had discovered that the first day of the conference was also my birthday, and when I walked into the Admiral’s Room at the Lord Nelson Hotel, he surprised me with a beautiful bouquet of flowers. I soon learned that this generous gesture was characteristic of Patrick, an excellent host and an excellent friend. May he rest in peace.

I took this photo of Patrick at the 2017 conference:

Here’s some wonderful news from JASNA about Student Memberships:

“For the remainder of 2024 through 2025, we are excited to offer free one-year JASNA Student Memberships to the next generation of Austen fans and scholars. Don’t miss this unique opportunity to join our community. Keep up to date with the latest on Jane Austen and her works and connect with others in your area and beyond who share your admiration for this beloved and influential author.”

A few more photos of springtime in Nova Scotia, taken by Brenda Barry and sent to me by her sister Sandra: pussy willows, a Downy Woodpecker, and a ghostly moon:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

“Wondering what will happen next” (a “scrapbook” post that begins with Shawna Lemay’s new book Apples on a Windowsill)

February 14, 2024

Celebrating Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and L.M. Montgomery’s 150th Birthday

I’m delighted to announce “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” and “‘A world of wonderful beauty’: L.M. Montgomery at 150,” two exciting projects I’m planning for later this year.

Contributors to the Sense and Sensibility blog series include:

Finola Austin, Elaine Bander, Deb Barnum, Sandra Barry, Cheryl Bell, Matthew Berry, Diana Birchall, L. Bao Bui, Kathy Cawsey, Carol Chernega, Lori Mulligan Davis, Lizzie Dunford, Susan Allen Ford, Paul Gordon, Heidi L.M. Jacobs, Natalie Jenner, Hazel Jones, George Justice, Theresa Kenney, Deborah Knuth Klenck, Emily Midorikawa, Laurel Ann Nattress, S.K. Rizzolo, Peter Sabor, Vic Sanford, Marilyn Smulders, Emma Claire Sweeney, Joyce Tarpley, Janet Todd, and Deborah Yaffe, along with two teenagers, Gail and Ria, who are reading S&S for the first time.

And for the L.M. Montgomery series (so far):

Lesley Clement, Brenton Dickieson, Trinna Frever, Sue Lange, Naomi MacKinnon, Nili Olay, Liz Rosenberg, Kate Scarth, and Marianne Ward.

I’m excited about both parties and I hope you, dear readers, will join the conversations! Feel free to invite friends as well—if they’re interested, they can subscribe on my website.

You can also find me on Instagram and Facebook.

On this February day (yet another snow day in my part of the world), let’s imagine we’re in a garden in Hampshire or Prince Edward Island, drinking raspberry cordial, currant wine, or Constantia wine—raising a glass in honour of the brilliance of Jane Austen and L.M. Montgomery.

“I should think Marilla’s raspberry cordial would prob’ly be much nicer than Mrs. Lynde’s.”

– L.M. Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables, Chapter 16

I took this photo of a glass of homemade raspberry cordial at the Blue Winds Tea Room in PEI a few years ago.

“I have just recollected that I have some of the finest old Constantia wine in the house that ever was tasted, so I have brought a glass of it for your sister.”

– Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility, Volume 2, Chapter 8

Many thanks to my friend Nili Olay for sending me these photos of Constantia wine.

The “Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility” will begin on June 20, 2024 and run through to the end of the summer.

Long-time blog readers will know that I like to celebrate significant anniversaries for Austen novels: I had fun celebrating the 200th anniversaries of Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, Emma, and Persuasion and Northanger Abbey here. But since I started in 2013 with P&P, I missed the chance to celebrate the 2011 anniversary of S&S with a blog series.

Thus, with the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth coming up in 2025, I’ve decided this is a good time to celebrate her first published novel.

“‘A world of wonder’: L.M. Montgomery at 150” will begin in October—because “I’m so glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” as Anne says in Anne of Green Gables—and run to the end of November. Montgomery was born on November 30, 1874.

A couple of other things that are coming up this year:

In May, my friend Naomi MacKinnon and I are hosting a readalong for Montgomery’s 1910 novel Kilmeny of the Orchard.

And I have some plans in the works for December, as we prepare to celebrate Jane Austen’s 250th birthday in 2025. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, if you’re interested, you can read about previous blog celebrations for novels by both Austen and Montgomery here.

I’m looking forward to celebrating with you! Here are a couple of old photos of my daughter, about to enjoy cake with her raspberry cordial at the Blue Winds Tea Room:

And I’ll add a photo of some forsythia branches given to me by my friends Sheila and Hugh Kindred the other day.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“Wondering what will happen next” (a “scrapbook” post that begins with Shawna Lemay’s new book Apples on a Windowsill)

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence” (a poem by Sandra Barry)

January 26, 2024

“Wondering what will happen next”

I’m reading Shawna Lemay’s beautiful and thought-provoking new book Apples on a Windowsill, a collection of essays on still life, memory, art, and marriage, and I’m fascinated by what she says about how a still life can both stop time and serve as a moment of suspense: “The question hovers: what happens next? And it gives us an interval to dream new possibilities.”

Shawna talks about wanting to “escape into a favourite movie where I know that the ending is a happy one,” such as “Bridget Jones’s Diary or an adaptation of Pride and Prejudice or Persuasion.” In life, she says, “we have no idea if the ending is a happy one. The thing most of us have in common is wondering what will happen next.”

Reading her words in an essay entitled “The Loophole” about how she’s “interested in the history and secrets and stories of things themselves,” I thought of what Anne of Green Gables says about how it’s easier to dream in a room where there are pretty things. Shawna writes, “I like rocks and odd china ornaments and chipped cups and smooth bowls. I like pearl earrings and old weathered chairs and water pitchers. I like fading flowers and green bottles and books. I like things. I like listening to the music and silence in things. What do they say about us, and what are they whispering to us about our lives and this world, this planet?”

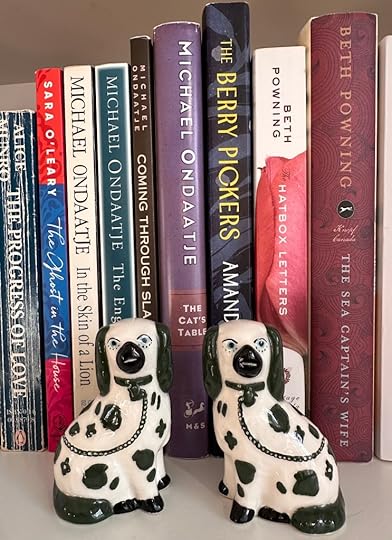

(Gog and Magog, replicas of the much larger ceramic dogs L.M. Montgomery owned, which make an appearance in Anne of the Island. “I think a great deal of those dogs,” says Miss Patty. “They are over a hundred years old, and they have sat on either side of this fireplace ever since my brother Aaron brought them from London fifty years ago. … Gog looks to the right and Magog to the left.”)

(Coffee mugs with broken handles, repaired and repurposed to hold pens and pencils and other supplies and treasures, including two “quill pens” made by my daughter when she was younger.)

(I think I’ll call this one, “Pearls and Dust.”)

(Fading flowers. I took these pictures last week, in between reading Shawna’s essays.)

“The still life can be a small world that speaks about the larger one,” Shawna writes. “It can be witness, consolation, a secret message, the arrow you launch through a narrow opening, a dream we once had or will have. A still life is in time but it also stops time, is out of time.”

Later in the same essay, she repeats these words: “A still life stops time, is out of time, occasionally offering the viewer that rupture/rapture.” Still life can bring a “moment of transcendence” that allows us to see “through to the other side,” an “opening or loophole where we drop into the sheer mystery of being.” To me, the experience sounds very much like what L.M. Montgomery describes as “the flash,” in Emily of New Moon. I quoted the passage here last month:

“It had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside—but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond—only a glimpse—and heard a note of unearthly music.”

Like Montgomery, Shawna uses the word “realm” to describe this world of mystery and beauty, but she maintains that it is here, rather than “beyond”: “The other realm,” Shawna writes, “is not beside this one, it is this one, and we only need a little light, a sense of composition, a love of the inadvertent, an appreciation for the humble, and there it is.”

“Everyone’s home is full of still lifes,” she says. “We make still lifes inadvertently all day long”: “the cereal box on the table by the jug of milk”; “the lunch bag on the counter beside briefcase or satchel and car keys”; the book “on a side table, along with a glass of water, our spectacles.” She suggests that “the most profound function of a still life” may be “to remind us that however messed up our lives are and have been, we can find order and harmony and calm out of the at times ridiculous horridness and tawdriness of daily existence. … We can bring forward the weight and heaviness that we have carried throughout our lives and bring it into the light.”

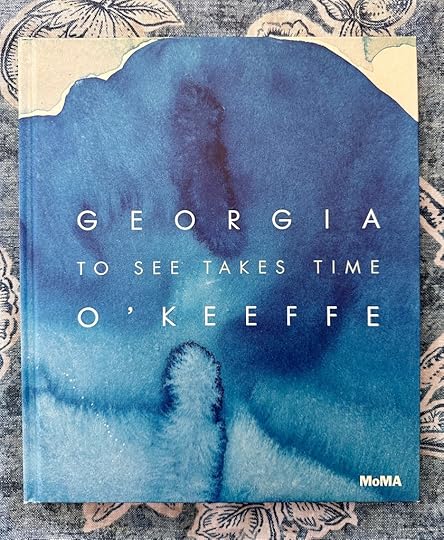

In an essay on “Women’s Lives, Women’s Still Lifes,” Shawna raises questions about finding the confidence to create art. She quotes a couple of powerful lines from Georgia O’Keeffe:

“I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing that I wanted to do.”

“It’s not enough to be nice in life. You’ve got to have nerve.”

Shawna writes that “one of the responses to a lot of work by women is to ignore it. Historically, creative women have been trivialised, especially those who had more than one talent.” Citing an article by Jonathan Jones, she gives Charlotte Brontë as an example. Jones writes of a self-portrait by the young Charlotte that he finds “unsettling” because of “the talent it shows. Could she have been an artist as well as a great writer—and how many other talented women have found their ability to draw trivialised or suppressed through the centuries?”

Shawna says that for her, part of the appeal of literature is that “it could be hidden,” and thus “more possible” than art: “you could do this alone, with a pen and paper.” “Which is why,” she says, “reading about Jane Austen hiding her work under her blotter, the supposed creak that alerted her to another’s presence, always spoke to my heart. I wasn’t bold. Not in the least.”

She quotes from Eavan Boland’s poem “The Rooms of Other Women Poets,” in which the poet wonders about other poets at their desks, reaching for the lamp as dusk falls. “We just want to work,” Shawna says. “I in my room, you in yours. I don’t want to be in competition with you, but to send my good wishes to you so that you can send yours to me.”

There’s a kind of magic in this wondering, this sending of good wishes to other poets and writers and artists at work in other rooms, other spaces. This connection with others who are drawn to create. This curiosity about what they, and we, will create next. This belief in possibility, and in the value of dreaming “new possibilities,” even though we have “no idea if the ending is a happy one.”

Those of you who live in Alberta (hello, dear friends and relatives!) might like to go to the book launch for Apples on a Windowsill, which is at Audreys Books Ltd. in Edmonton on February 1st at 7pm.

I wrote about Shawna’s novel Everything Affects Everyone here last year: “Secrets that everyone knows.”

You might also be interested in an interview Shawna did for Open Book, in which she answers questions and also asks many of her own. “What can the process of assembling a still life tell us about how we can make our lives? … Can looking closely at art and things improve our everyday lives? If we change one thing in a composition, how does that change another? And if we can recompose a still life, can we recompose our lives, our thinking?”

This last question makes me think of something my grandfather said years ago: my father asked, “how are you?,” and Grandpa answered, “Better, since I changed my attitude.” I and several members of our extended family think of this exchange often, especially in challenging times.

Kerry Clare wrote about Apples on a Windowsill on her blog recently: “while it’s called Apples on the Windowsill, it’s as much about lemons, not only about how the light falls on their unwinding rinds, but also what we do when life gives them to us. Which is to say, put them in a bowl and take their picture, and notice them, how they absorb the light, and how they change….”

(A couple of photos I took for an online photography class a few years ago.)

I have a few other things to share with you today. First, I was charmed by Margaret Renkl’s description of a New Year’s resolution she made in 2021: “Resolving to write a letter every day would help me use up the stamps and notecards accumulated over many years, repudiate the entire virtual world, and honor my grandmother at the same time. It’s one of the nicest resolutions I’ve ever made.”

Next, Diana Birchall’s impressions of the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM in Denver, Colorado, last November: “Jane in Denver.” I attended the conference online, which was lovely, but also made me miss the joys of attending in person. I was especially sad to miss seeing Syrie James’s play “Pride and Prejudice: Six Rocky Romances.” I have fond memories of watching Syrie and Diana and other friends performing at the 2014 AGM in Montreal, in a play the two of them co-wrote called “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park.” (The blog post I wrote after the 2014 AGM includes a photo of the cast.)

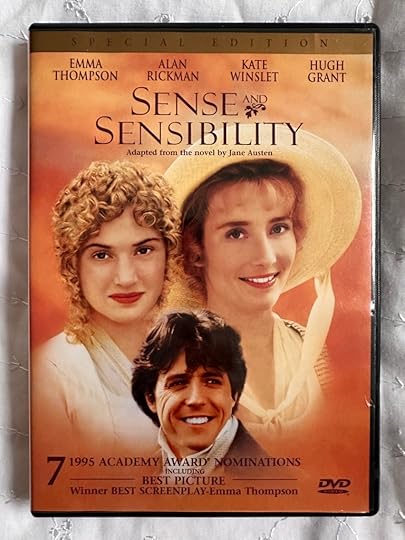

Laurel Ann Nattress wrote a lovely blog post last Sunday about the 1995 Sense and Sensibility movie, praising (among other things) the cast, Emma Thompson’s use of humour and irony in the Oscar-winning screenplay, and the symbolism of the coins thrown into the air in last scene: “This story is all about cash and those who have it, and those who do not.”

Some of you might be interested in the call for papers from the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies for a special collection entitled “#Maud150: Back to the Future.” November 30, 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of Montgomery’s birth, and “#Maud150 is a time to reflect, reappraise, and envision: we particularly invite submissions–scholarly articles and creative work (written, visual, or audio-visual)–about celebration and commemoration and those that consider the past, present, or future in relation to Montgomery’s art, life, context(s), or legacies.”

This past Wednesday, January 24th, was the birthday of Edith Wharton, who was born in New York City in 1862. I enjoyed listening to this podcast from the American Writers Museum, in which Wharton scholars Emily J. Orlando and Anne Schuyler talk about Wharton’s life and work.

Here are some photos I took on a recent trip to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and the lighthouse at Cape Forchu:

As always, the “bend in the road” makes me think of the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables.

And I’ll end with a photo from Point Pleasant Park in Halifax:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence” (a poem by Sandra Barry)

“Happy 100th Birthday to Emily of New Moon!”

I’ll be back in February—see you then.

January 12, 2024

“While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence”

For today’s blog post, I have the great pleasure of introducing a poem by Sandra Barry. You might remember her beautiful poem “Old Rusty Metal Things,” which I shared here last April, and the wonderful photos taken by her sister Brenda Barry, which I’ve included in several blog posts over the past year or so. I asked Sandra recently if she’d like to share another poem with all of you, and I was delighted when she said yes and sent me “While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence.”

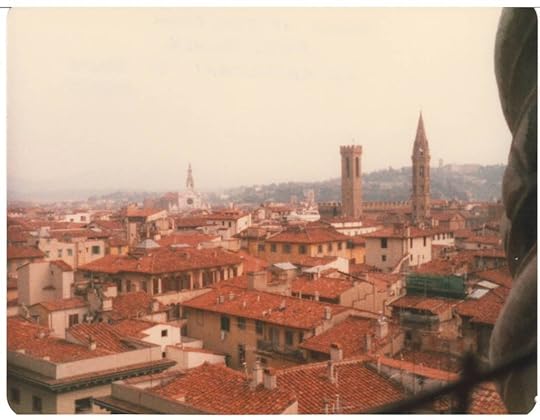

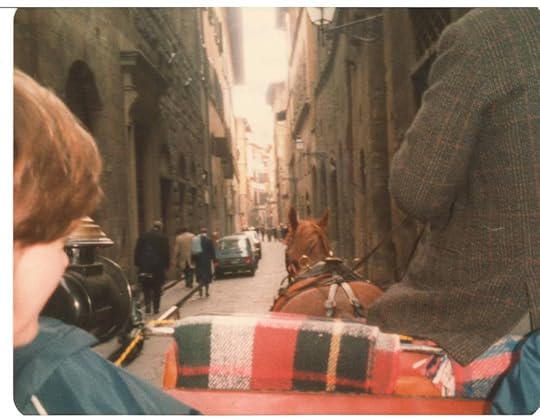

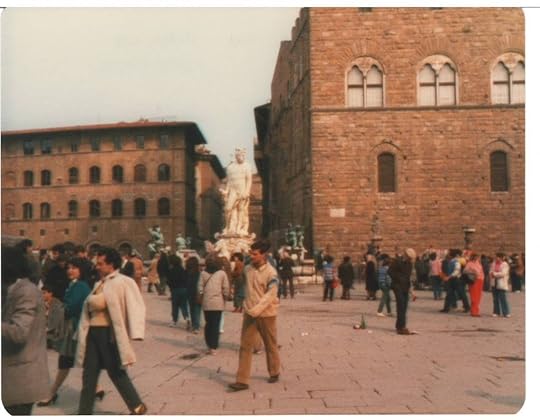

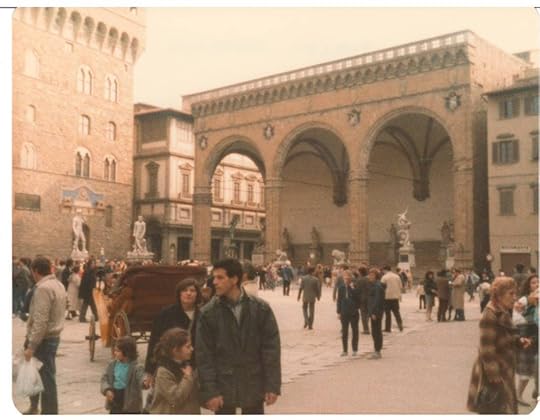

This poem was inspired by Sandra’s trip to France and Italy in April of 1984, almost forty years ago, with her sisters Donna and Brenda and friend Pam. She writes, “That brief visit to Florence was memorable, but it had left my active thoughts for years until I found a used copy of Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence in some used bookstore—I am not much of a fan of her fiction (she wrote an infamous novel, The Group, about Vassar, with one character supposedly based on Elizabeth Bishop—I couldn’t get past page 5 of it). But I like her non-fiction, which I find much more lively. Anyway, I read the Florence book quickly and it triggered a flood of long forgotten memory—quite the experience—and I immediately went looking for the photos from that trip and found that they reflected most of the vivid memories I had retained. Travel was so important to Bishop—and she did visit Italy at least once during her life—though it was Rome that impressed her most.”

Sandra says, “The photos were taken by Donna with a tiny film camera she had—might have even been one of those disposable jobs. They are quite poor quality, but there is something about their vagueness and distance that actually works with the poem, which is a memory poem.”

Sandra is a freelance editor and an Elizabeth Bishop scholar, and her book Elizabeth Bishop: Nova Scotia’s “Home-Made” Poet, was published by Nimbus in 2011. You can read more about both Sandra and Bishop in the introduction to “Old Rusty Metal Things.”

(I wish I could show the poem single-spaced, but for some reason, WordPress won’t let me change the format.)

While reading Mary McCarthy’s The Stones of Florence

Casting my mind back to my own brief encounter

—an afternoon overwhelmed by noise and stone;

the milky sunshine, the vague sky contrasting

the perpendicular,

the narrow straight up streets and a short expensive

carriage ride. Two photographs. One: a vanishing point

from the seat of the carriage, the claustrophobic height

of heavy stone receding to where my memory resides.

I do not remember the soft brown horse, the pale green

tweed of the driver. I do remember a glimpse

of stunning black eyes among thousands.

Two: the soft brown horse freed of his tourist haul

feeding from a bag of oats hung on his harness,

his flanks and back covered by a blanket

to keep the April chill away.

The narrow streets have opened into a square

walled by severe history. In spite of the evidence

there is no “local colour” in Firenze.

Everywhere mythical statues compete with humanity,

so many pasts in one place is disorienting.

I remember seeing only surfaces, hardly sensing

the centuries. Yet here, in another photograph,

is Neptune in his fountain, the Arno god who wanders

the Piazza della Signoria under the full moon.

And there I am with a friend (and countless strangers)

dwarfed by the elegant arches of Loggia dei Lanzi,

which harbours so much violence frozen in marble,

sealed in bronze. The matrons and lions

bear witness to rape and decapitation;

the crowds barely seem to notice.

Did we know something beyond Michelin?

Or did we herd into the Piazza like so many generations

of Florentines anticipating a harangue

—the harangue of guidebooks and postcards.

The Florentines ignored us grandly.

I stand there, caught in one moment;

but I do not remember what I felt.

I remember the rigorous ascent of Giotto’s bell tower

(the Duomo, the Dome, was closed for repair).

There is no nearby place to see all of Santa Maria

del Fiore. It rises like a mountain from a sea

of red tile, crowded by buildings, traffic, people.

I remember only din suddenly falling

away, immensity, silence spiralling into darkness.

From the top of the tower, one photograph

dominated by the white-washed sky

and the “cruel tower of Pallazo Vecchio

piercing the sky like a stone hypodermic needle.”*

In relative terms, a quick jab from Florence,

and how unaware am I still of Dante’s exile,

Michelangelo’s vanity, Leonardo’s obsessions,

Cellini, Donatello, Uccello, Galileo.

And the buried life and death of Etruscan augury.

The Uffizi was closed, so the portraits

had no chance to stare at us, four bewildered

maidens wandering among the columns, blinking.

* McCarthy, p. 36.

Sandra writes that she and her friend Pam are in the photo above, of the Piazza del Signoria, “standing looking stunned among the throng.”

She adds that Mary McCarthy “is one of the talking heads in the wonderful 1989 documentary about Elizabeth Bishop in the Voices & Visions series that can be found and watched on the Annenberg Foundation site.”

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages, and I’m sure Sandra will be, too. Thanks for reading!

If you missed my recent post on L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, you can find it here. I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with a scrapbook blog post—see you then.

December 29, 2023

Happy 100th Birthday to Emily of New Moon!

The first novel in L.M. Montgomery’s trilogy about a young writer, Emily Byrd Starr, was published in 1923. One hundred years later, although Emily of New Moon has many fans, she isn’t nearly as well-known as Montgomery’s most famous heroine, Anne of Green Gables. Elizabeth Egan asked recently why Emily is “forever in Anne’s shadow,” and wondered if it’s “possible that her story holds up even better than Anne’s after all these years.”

Emily of New Moon is one of my favourite novels, and after I had finished The Story Girl and The Golden Road last month, I decided to reread the first Emily novel again during this anniversary year. The opening chapter is deeply moving, with its account of Emily’s father’s death and her feeling of being alone in the world. This is also where we learn about “the flash”: “It had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside—but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond—only a glimpse—and heard a note of unearthly music.”

On this particular evening, “the dark boughs against that far-off sky” are the source of “the flash” and that note of music. Like Sara Stanley in The Story Girl, who thinks in colours, Emily has a form of synesthesia, as images give her access to “unearthly music.”

Emily’s unshakeable conviction that she is a writer is the main highlight for me, every time I reread this novel. She will write even if she doesn’t have paper, even if she is forbidden to write because her aunt believes novels are wicked, even if teachers or classmates or relatives—or friends and mentors—mock her.

She finds inspiration in nature, where she feels alive to the possibilities of the future: in the spruce barrens, she feels that “Anything might happen there—everything might come true” (Chapter 1). She reminds me of Sara Stanley here: “‘I always feel so satisfied in the woods,’ said the Story Girl dreamily, as we turned in under the low-swinging fir boughs. ‘Trees seem such friendly things’” (The Story Girl, Chapter 28). When she is told she is “not of much importance,” Emily declares, like Jane Eyre before her, that “I am important to myself” (Chapter 3; Jane says, “I care for myself. The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself.”)

I read recently that if you “think of everything as potential material,” then “you can bear almost anything,” and I wonder if it’s true. Abigail DeWitt says she teaches her writing students this trick.

When Emily’s relatives are busy passing judgement on her, she feels “She would have given anything to be out of the room.” At the same time, however, “in the back of her mind a design was forming of writing all about it in her old account book. It would be interesting. … she felt that she would rather like to write it all out” (Chapter 3).

I thought of this passage again earlier this week when I reread Madeleine L’Engle’s memoir A Circle of Quiet (recommended by my sister Bethie). L’Engle writes that after she had received yet another rejection letter on her fortieth birthday, after a decade of seeing A Wrinkle in Time and other novels rejected, she felt she needed to stop writing. She believed she was being told to “Stop this foolishness and learn to make cherry pie.” She “covered the typewriter in a great gesture of renunciation” and walked around the room, sobbing. However, she stopped suddenly when she realized that while she was crying, her “subconscious mind was busy working out a novel about failure.” She uncovered the typewriter. “I had to write,” she says.

At school, when Emily is taunted by classmates who quiz her about whether she can sing, dance, sew, cook, knit lace, or crochet—the answer is always “no”—she says that one thing she can do is write poetry, and “at that instant she knew she could” (Chapter 8). Like Fanny Price in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, her education is seen as defective because she doesn’t possess the usual “accomplishments” of a young lady-in-training. Fanny’s cousins find her “prodigiously stupid” because she hasn’t memorized lists of rivers and kings and because she calls the Isle of Wight “the Island, as if there were no other island in the world” (Volume 1, Chapter 2). I expect Anne Shirley and Emily Starr would see Fanny as a kindred spirit, though for them “the Island” is Prince Edward Island.

Writing, for Emily, proves to be a way of healing grief and sorrow. Through writing long letters to her late father, she finds that “The bitterness died out of her grief” because “Writing to him seemed to bring him so near” (Chapter 9).

When her teacher calls her poems “trash” and tries to burn them, Emily vows to protect her writing with her life: “they should not get her poems—not one of them, no matter what they did to her ” (Chapter 16). Yet the experience is so traumatic that she is unable to write about it: “The shame of it all was too deep and intimate to be written out, and so she could find no relief for her pain.”

I like the passage in which Emily does battle with Aunt Elizabeth over the book she’s reading about the human body, which “tells about everything that’s inside of you.” She’s currently reading about the liver. Aunt Elizabeth is “horrified”: “This was worse than novels. … Things that were inside of you were not to be read about” (Chapter 21).

Like Montgomery herself, Emily finds inspiration in a poem about “The Alpine Path” (the title of Montgomery’s autobiography):

Then whisper, blossom, in thy sleep

How I may upward climb

The Alpine Path, so hard, so steep,

That leads to heights sublime.

How I may reach that far-off goal

Of true and honored fame

And write upon its shining scroll

A woman’s humble name.

At age twelve, Emily writes, “I, Emily Byrd Starr, do solemnly vow this day that I will climb the Alpine Path and write my name on the scroll of fame” (Chapter 27).

Montgomery says in her autobiography, “It is indeed a ‘hard and steep’ path; and if any word I can write will assist or encourage another pilgrim along the way, that word I gladly and willingly write.”

Emily believes in the power of books to create community: “Books were Emily’s friends wherever she found them,” and she insists to Aunt Elizabeth that “I thought books belonged to everybody” (Chapter 6).

Over the past century, Emily of New Moon has inspired countless writers, with Emily’s firm commitment to her vocation. Writing is as essential to her as breathing: “She must write stories—and Aunt Elizabeth must know it—that was the way it had to be. She could not be false to herself in this—she could not pretend to be false” (Chapter 29). Like Madeleine L’Engle, who says in A Circle of Quiet that “It was not up to me to say I would stop, because I could not,” Emily feels she doesn’t have a choice: “Why, I have to write—I can’t help it by times—I’ve just got to” (Chapter 31).

Her belief in herself and her work sustains her through repeated conflicts with Aunt Elizabeth and through conversations with people who appear to be on her side, including Father Cassidy and Dean Priest. Elizabeth Rollins Epperly writes in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance that “On the surface of it, the males, as Judith Miller says, ‘seem to encourage writing,’ but the underlying and encoded messages about woman’s place in the male literary establishment eventually make their quality of support suspect (not Cousin Jimmy’s or her father’s, but then Cousin Jimmy is ‘simple’ and her father is dead).” Father Cassidy “does not take her writing seriously, whatever he may say to her. To many readers this will be a chilling chapter—though Montgomery may not have meant it to be.” Epperly suggests that “his patronizing is but a gentle prelude to the caressing contempt Dean himself will later show for Emily’s ‘pretty cobwebs.’”

When Emily reaches out to grasp a “magnificent spray of farewell summer” (asters) at the edge of a cliff and slides down the slope toward the rocky shore, she is rescued by Dean, who at first seems like a kindred spirit (Chapter 26). He understands that she must write: “you have the itch for writing born in you,” he says. “It’s quite incurable.” He asks what she’s going to do with it, and she replies, “I think I shall either be a great poetess or a distinguished novelist.”

Like Father Cassidy, who has mocked Emily’s epic poem—“One av the seven original plots in the world”—Dean finds her ambition amusing: “Having only to choose,” he says. “Better be a novelist—I hear it pays better.” Even the people who seem to understand her vocation are as tyrannical and threatening as Aunt Elizabeth—or perhaps even moreso, since at least Emily knows where she stands with her aunt. Dean announces that her life is no longer her own: “your life belongs to me henceforth. Since I saved it it’s mine. Never forget that.” Although she responds at that moment with “an odd sensation of rebellion”—she “flung the big aster on the ground and set her foot on it”—she is later drawn to Dean.

As Epperly writes, “This is the most important gesture in all three of the Emily books—instinctively Emily fights against the power that wants to dominate her. And yet she leans towards Dean Priest, bends to him in the subsequent episodes, and does not understand that she, here, has rejected only part of his domination in refusing to acknowledge his right to own her. He will have to learn that, whenever she has accepted his judgment in place of hers, she has added to the cobweb fetters he flings round her.”

I’m interested in Alice Munro’s assessment (in her introduction to the New Canadian Library edition of the novel) of Dean Priest as an “invader,” who “disturbs the book so that the author, after a while, hardly knows what to do with him.” Mary Henley Rubio says in her biography of Montgomery that Dean may be a ‘Priest,’ but to adult readers he begins to feel unwholesome, more like a sexual predator than an older friend.” In the later books he’s also even more dismissive of Emily’s writing. “I’d hate to have you dream of being a Brontë or an Austen—and wake to find you’d wasted your youth on a dream,” he says to her in Emily’s Quest (Chapter 4). As Epperly writes, “it is Emily’s writing self, her very essence, that he eventually tries to destroy.”

Poetry, Munro says, is Emily’s response to “the flash,” a moment of joy, while prose “is her way of dealing with people, and often with situations in which she is powerless. We’re there as Emily gets on with this business, as she pounces on words in uncertainty and delight, takes charge and works them over and fits them dazzlingly in place, only to be bewildered and ashamed, in half a year’s time, when she reads over her splendid creation. This is wonderfully done. L.M. Montgomery makes us believe in ‘the flash,’ the moment of vision, the writing energy, the desperate commitment, of a female child living on a farm in Prince Edward Island….”

I like Munro’s conclusion about what mattered to her most when she first read Emily of New Moon, which was also “what was to matter most to me in books from then on,” and that was “knowing more about life than I’d been told, and more than I can tell.”

After I had finished rereading Emily of New Moon, I happened to read Munro’s story “Labour Day Dinner” (from The Moons of Jupiter), in which seventeen-year-old Angela, who has spent the summer reading “Anna Karenina, The Second Sex, The Norton Anthology of Poetry, The Autobiography of W.B. Yeats, The Happy Hooker, The Act of Creation, [and] Seven Gothic Tales,” sounds like Emily as she writes in her diary: “I want to have a truthful record of my whole life. How to keep oneself from lying I see as the main problem everywhere.”

Just as I enjoy returning to Anne Shirley’s “bend in the road” or Sara Stanley’s fascination with roads “because you can always be wondering what is at the end of it,” I loved revisiting Emily’s description of “the To-day Road, the Yesterday Road and the To-morrow Road” (Chapter 12). The To-day Road is “lovely now,” the Yesterday Road “used to be lovely,” before “Lofty John cut some trees down,” and the To-morrow Road is “just a tiny path in the maple clearing and we call it that because it is going to be lovely some day, when the maples grow bigger.” This passage made me think of three specific trees I have loved over the years—maple, spruce, and elm—all of which I mourned when they were cut down. And it made me appreciate the trees around our new house—maple, birch, elm—even more than I already did, and I feel inspired to plant another tree, maybe in the spring.

The three roads also brought back the memory of a long run on a prairie highway in the summer of 2015, when I was training for a half marathon. I set off that morning without thinking carefully about how far I would go (I never have been very precise about training for races), and I headed out of town on the highway that led to the cabin at the lake in southern Alberta that had been in my family for decades. I could have run all the way there, but then I might have had to call someone to pick me up. I stopped about halfway and took this photo.

I realized that I was, in a way, trying to run to the past, to the cabin as it was when I was a child, and no matter how carefully I trained for any distance, I would of course never be able to get there. I suppose I was running on the “Yesterday Road,” trying to reach what Montgomery calls the “golden road of youth,” which we can visit only in memory.

I turned around and ran back to town, back into the present, in which my grandparents’ health was failing, and I needed to learn how to say goodbye. They both died within the following year. In the summer of 2016, I visited Alberta again, and thought about them as my family and I drove around the province visiting relatives and friends. That summer, when I was out running, I often listened to Kev Corbett’s song “On the River Off the Lake”: “I kiss the air when I’m here / I kiss the water / I kiss the memory of my grandmothers and fathers.”

I also wrote about Emily of New Moon back in 2017, when my friend Naomi hosted a readalong for the three Emily novels:

“‘I am important to myself’: Emily of New Moon”

Many thanks to all of you for reading these blog posts over the past year. I’ll look forward to seeing you here in January. Happy New Year!

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 22, 2023

Season’s Blessings

Season’s Blessings and best wishes at Christmas to you!

I found this postcard at Effex Vintage last month, and I thought I’d send it to all of you with a wish for peace and happiness for you and your loved ones, and for people around the world.

I’m rereading L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon because this year is the 100th anniversary of the novel’s publication. I was touched by what Emily writes about the “Disappointed House” in one of her letters to her father:

I am finishing the Disappointed House in my mind. I’m furnishing the rooms like flowers. I’ll have a rose room all pink and a lily room all white and silver and a pansy room, blue and gold. I wish the Disappointed house could have a Christmas. It never has any Christmases.

Oh, Father, I’ve just thought of something nice. When I grow up and write a great novel and make lots of money, I will buy the Disappointed House and finish it. Then it won’t be Disappointed any more.

(Chapter 20)

In last Friday’s post, “Where to look for the threads,” I mentioned Jesmyn Ward. This morning I followed a thread from the Poets & Writers email newsletter to their 2013 profile of her. A few days ago I read a profile of her in the current issue of Vanity Fair, and I like what she says about how Mississippi has given her “one of a writer’s most cherished gifts. ‘This place taught me to sit very still, and to observe and to listen, and then to take what I observed and to translate that into language,’ she says. ‘This place taught me poetry.’”

In the new year, I won’t have time to write blog posts every Friday, but I’ll aim to write at least once a month, as I love writing these posts and I enjoy the conversations we have here and on social media, and in letters and emails. Many thanks to all of you for being here. I’m grateful for your company! Before the year ends, I’ll write one more post about Emily—see you next Friday.

Photos from the Annapolis Valley, by Brenda Barry

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!

December 16, 2023

Sense and Enthusiasm

Happy 248th birthday to Jane Austen!

Last summer’s roses in the Historic Gardens at Annapolis Royal, photographed by Brenda Barry

To celebrate, I thought I’d write about an Austen-inspired novel I read recently. Polly Shulman’s novel Enthusiasm is a delightful YA romance inspired by Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, but also by less well-known elements of Jane Austen’s life and work, including a novel written by her niece Anna that was originally entitled “Enthusiasm” and later renamed “Which is the Heroine?” In a letter to Anna, Jane said, “I like the name ‘Which is the Heroine’ very well, and I daresay shall grow to like it very much in time; but ‘Enthusiasm’ was something so very superior that my common title must appear to disadvantage” (August 10, 1814). I missed Shulman’s novel when it was published back in 2006, and I’m grateful to my friend Lisa for giving me a copy.

“There is little more likely to exasperate a person of sense than finding herself tied by affection and habit to an Enthusiast,” says the narrator, Julia Lefkowitz, lamenting the extremes of her best friend and next door neighbour Ashleigh Rossi’s various enthusiasms, the latest of which is “the joys of Miss Austen’s work.” Usually, Julia follows where Ashleigh leads, but in this case, she has introduced Ashleigh to Jane Austen, and soon the Enthusiast is attempting to dress like an Austen heroine, addressing Julia as “my dear Miss Lefkowitz,” and plotting to find heroes for both of them by crashing the fall formal at a nearby prep school for boys, or, rather, “young gentlemen.” And Julia is worried that Ashleigh’s passion for Austen will overshadow her own. Nevertheless, she agrees to her friend’s plan, and with the convenient assistance of two young men who agree to act as their escorts, they attend the formal and begin to fall in love.

The problem, however, is that they can’t agree which of the young men is Mr. Bingley, and which is Mr. Darcy, or which of them is Jane Bennet or Elizabeth Bennet. Despite the contrast Julia draws between herself as the sensible one and Ashleigh as the Enthusiast, it doesn’t seem to have occurred to her that they might be Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, rather than Jane and Elizabeth.

I loved the names and nicknames in this novel. One of the young men, for example, is named Charles Grandison Parr, presumably after the hero of one of Austen’s favourite novels, The History of Sir Charles Grandison, by Samuel Richardson. Another student at the prep school is named Alcott Fish. The public school Julia and Ashleigh attend is called Byzantium High, and the school’s literary magazine is Sailing to Byzantium. And Julia thinks of her stepmother, Amy, as the “Irresistible Accountant,” or “I.A.” for short.

I also appreciated the way poetry is part of the way these teenagers communicate with each other, whether they’re analyzing speeches from Romeo and Juliet, accidentally speaking in iambic pentameter, pinning poems to the oak tree between Julia’s house and Ashleigh’s, or discussing assonance, alliteration, or acrostics. I don’t know how many teenagers actually talk this way, but it’s certainly fun to read about.

There are a few more Austen-related things I’d like to share with you today. First, a lovely paragraph from a blog post that Ellen Moody wrote a few years ago, in which she draws a comparison between the way she reads Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry and the way she reads Jane Austen’s novels. She writes that in Bishop’s “Sonnet” (1928) she finds “Bishop keeping herself calm by making order and harmony through making a poem which can harness the very rhythms of her heartbeat and body as she writes and we read it. This is the way I read Jane Austen’s novels, say Emma: the orderly rhythm of her sentences, their elegance and deeply felt content within patterns soothes and keeps me calm, strengthens me. This is what Bishop is doing through her very finger-tips, her lips, her whole body healing.” The poem opens with a “need of music that would flow / Over my fretful, feeling finger-tips, / Over my bitter-tainted, trembling lips, / With melody deep, clear, and liquid-slow.”

Ellen wrote a beautiful guest post for the blog series I hosted for the 200th anniversary of Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Persuasion: “‘For there is nothing lost, that may be found’: Charlotte Smith in Jane Austen’s Persuasion.”

Earlier this week on Vic Sanborn’s wonderful blog Jane Austen’s World, Rachel Dodge made a list of ways to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday, in addition to reading/rereading the novels. She suggests making a donation to the Courtyard Restoration Appeal at Jane Austen’s House Museum, Chawton Cottage. Her list also includes Jane Austen’s Virtual Birthday Party, which is happening later today (8pm GMT; tickets are available from Jane Austen’s House Museum here). I won’t be able to attend, but if any of you attend the celebration, I would love to hear about it! Please comment on this post or send me an email.

Rachel suggests making a sponge-cake, and provides a link to a recipe. “You know how interesting the purchase of a sponge-cake is to me,” Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra in 1808. In previous years, I’ve sometimes made syllabub for Jane’s birthday, using Kim Wilson’s recipe in Tea with Jane Austen.

The Pride and Prejudice scarf in the background of this photo of Kim’s book was a present from my friend Sandra Barry, an Elizabeth Bishop scholar (and sister of Brenda Barry, whose photos I often include in blog posts).

Do any of you have a favourite recipe for sponge-cake or syllabub, or another Austen-inspired dessert? Like Shawna Lemay, who likes to hear from friends about “a scone with plum jam,” or “sour cherry pie,” or “a new scarf,” I like to hear about such details. As I wrote in a blog post earlier this year, I’m a fan of Shawna’s theory of “The Sponge-Cake Model of Friendship.”

In her blog post for Jane Austen’s birthday, Deborah Barnum of Jane Austen in Vermont quotes George Austen’s letter to his sister about Jane’s birth: “We have now another girl, a present plaything for her sister Cassy and a future companion.”

Deb suggests joining/renewing membership in the Jane Austen Society of North America and/or donating to Chawton House, through the North American Friends of Chawton House.

From Deb’s post I learned of plans for a new statue of Jane Austen at Winchester Cathedral, to be unveiled in 2025, the 250th anniversary of her birth. The sculptor, Martin Jennings, says, “I have represented her rising from her table at Chawton as someone arrives at the door, moving in front of her work as if to disguise it. It is important for me that she should be accompanied by the tools of her trade, so that she is indissolubly associated with her working life.” You can see images of the memorial statue, and share feedback if you wish, on the Cathedral website.

Gillian Dow, former Executive Director of Chawton House, says, “I admire the quietly confident Jane Austen depicted by Martin Jennings here. She gazes into the distance, as if she were wishing the manuscripts composed at her writing table good fortune as they travel into the world to make their own way in it.”

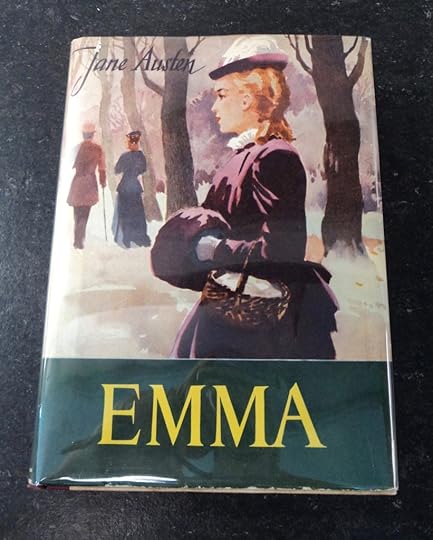

Gillian wrote a guest post on “Emma Abroad” for my Emma in the Snow blog series in 2016, complete with photos of a 1951 Finnish book cover featuring “Emma in the Snow” and of George Justice’s edition of Emma, which Gillian read in the French Alps. She argues that even though many readers participate in and find value in literary tourism, “an immersive fictive experience … cannot, must not, depend on where one is when one reads a book. Whether sitting under an English Oak, next to a cactus, or up a brutalist skyscraper in the centre of a metropolis, one creates the world of a novel oneself.”

I agree with what Gillian says about the experience of reading. Books can take us anywhere, to real places and places that exist only in the imagination. As Emily Dickinson says, “There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away,” and “This Traverse may the poorest take / Without oppress of Toll.”

Someday, I’d love to go to Winchester for coffee (or tea) with my sister Bethie and the new Jane Austen statue. In the meantime, I can open a copy of Pride and Prejudice and read, for example, about a very impatient Elizabeth Bennet serving coffee:

Darcy had walked away to another part of the room. She followed him with her eyes, envied every one to whom he spoke, had scarcely patience enough to help anybody to coffee; and then was enraged against herself for being so silly!

“A man who has once been refused! How could I ever be foolish enough to expect a renewal of his love? Is there one among the sex, who would not protest against such a weakness as a second proposal to the same woman? There is no indignity so abhorrent to their feelings!”

She was a little revived, however, by his bringing back his coffee cup himself; and she seized the opportunity of saying,

“Is your sister at Pemberley still?”

“Yes, she will remain there till Christmas.”

“And quite alone? Have all her friends left her?”

“Mrs. Annesley is with her. The others have been gone on to Scarborough, these three weeks.” She could think of nothing more to say; but if he wished to converse with her, he might have better success. He stood by her, however, for some minutes, in silence; and, at last, on the young lady’s whispering to Elizabeth again, he walked away.

(Volume 3, Chapter 12)

(My coffee cup in this photo is actually a Glühwein mug from the Bonner Weihnachtsmarkt, which is where Bethie and I celebrated Jane Austen’s birthday last year, near the statue of Beethoven in the Münsterplatz.)

Speaking of frigates and books and memorials, I also want to share with you a splendid memorial tribute to Lieutenant Commander Francis Austen RN (1924 – 2023): Remembering Jane Austen’s Great Great Nephew, written by my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred. I have fond memories of meeting Francis Austen at the Jane Austen Society of the UK conference here in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 2005. Sheila outlines his naval career, which included serving as a midshipman and later as a sub-lieutenant in the frigate HMS Kent in 1943-44.

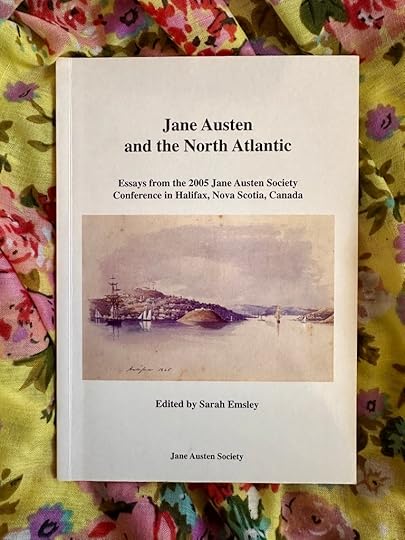

Francis’s grandfather, Lieutenant Herbert Grey Austen RN, made several sketches of Halifax Harbour when he was stationed here in the 1840s, one of which appears on the cover of Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, a collection of essays from the 2005 conference.

Sheila writes that Francis Austen was “genial, empathetic and had the gift of making people feel welcome.” He “talked engagingly about Jane Austen and her family. Particularly memorable were his stories about the French Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic Wars as they affected the careers of his ancestor, Admiral Francis, and the Admiral’s younger naval brother, Charles (1779 – 1852), who had also served on the North American Station from 1805 – 1811.”

If you’re interested, you can find out more about Jane’s brothers Francis and Charles and their families and their time on the North American Station in the walking tour Sheila and I created for the 2017 Jane Austen Society of the UK conference, which was also held here in Halifax: Austens in Halifax.

(I seem to have an endless collection of scarves; this stunning yellow scarf was a gift from another member of the Austen family at the 2017 conference.)

More of Brenda Barry’s photos from the Historic Gardens:

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. I’m always interested to read your comments and messages. Thanks for reading!