Roz Savage's Blog, page 25

January 18, 2018

Crafting a Career in Conversation

Last week I wrote a blog post about Crafting a Career in Conservation. Sometimes it feels more like I’m crafting a Career in Conversation, because for sure there is a lot of talking involved in my work – meetings, Skype calls (or these days, Zoom – much better), conferences, and speeches.

And talking matters. As Margaret Mead wrote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” And how does that small group of citizens communicate with each other? They talk.

And talking matters. As Margaret Mead wrote, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” And how does that small group of citizens communicate with each other? They talk.

I don’t know if you’ve noticed this in your life, but I definitely feel that a new idea has very little substance while it exists purely in my head. One day, on a whim, I can decide that I am going to do something about plastic pollution in the oceans, say. The first time I think the thought, it is a fragile, tentative little resolution. But the more times I think about it, the stronger that idea starts to get wired into my brain. But it’s all still internal. There are no sensory experiences to reinforce the idea – it’s just a notion.

So I decide to ponder my new idea during a session with my journal. I write about my new resolution. Now I’m starting to add other sensory layers to the idea. I can see it written on the page. I have felt my hand, holding the pen, shaping the letters of the words of the idea. It is gaining more substance.

But it still lies purely within me. It’s still my little secret. If I’m serious about it, the time has come to share. And so I start to talk about it. I share it with my partner, with my friends, my mother. I might write about it on this blog. I start going to conferences, where I listen to speakers talking about plastic pollution, I have conversations with other people, who bring new perspectives to my idea, and I hear myself saying out loud that I have decided to do something about this problem.

Now we’re talking – literally. Those interactions add layer upon layer to the neural connection in my brain that started out as that feeble little first notion. A whole web of connections builds up around it, representing the additional pieces of information I am gathering, the memories of the conversations that have contributed to the development of my idea, and the further thoughts I have had on the subject.

Now we’re talking – literally. Those interactions add layer upon layer to the neural connection in my brain that started out as that feeble little first notion. A whole web of connections builds up around it, representing the additional pieces of information I am gathering, the memories of the conversations that have contributed to the development of my idea, and the further thoughts I have had on the subject.

(Of course, a neuroscientist wouldn’t be able to point to my head and say, “there’s the plastic pollution part of her brain”, because it’s not physically localised like that, but nonetheless that web of connections is a very real thing.)

And so gradually I become something of an expert. I have immersed myself in this new area, until at some point, either gradually or maybe in a blinding flash, I know what I am going to do. I figure out how I can be a part of the solution. The multitude of conversations has led me to a new point of knowledge and insight – and potential action.

The problem arises when the potential action doesn’t become actual action. The temptation can be to have more conversations, to embellish the idea for the potential action, adding more and more bells and whistles until it is a thing of beauty to behold.

Maybe I decide to commission a beautiful report, complete with gorgeous graphic design, charts, tables, photos, and attractive fonts. Don’t get me wrong – reports have an important place, and I am extremely grateful for the many well-put-together reports available for free online, which are repositories of incredibly useful information. (If you’re interested in the future of the world, here are a couple that I particularly recommend: A Finer Future is Possible, by the Club of Rome, and the Living Planet Report 2016, by WWF and ZSL.)

Maybe I decide to commission a beautiful report, complete with gorgeous graphic design, charts, tables, photos, and attractive fonts. Don’t get me wrong – reports have an important place, and I am extremely grateful for the many well-put-together reports available for free online, which are repositories of incredibly useful information. (If you’re interested in the future of the world, here are a couple that I particularly recommend: A Finer Future is Possible, by the Club of Rome, and the Living Planet Report 2016, by WWF and ZSL.)

The danger comes when the publication of the report – or never-ending conversations – is seen as a substitute for action, rather than as the starting point for doing something.

Maybe you’re not an action kind of a person. You’re good at research and strategy. That’s all good – ally yourself with people who are good at action, so you can hand off your well-researched strategy to them to bring into reality.

But sometimes there is something more sinister at work – fear. As the military saying goes, no battle plan ever survives first contact with the enemy. So maybe you’re afraid that your beautiful theory won’t survive its first encounter with reality, afraid it will fail. Get over it. No battle plan ever survives first contact with the enemy.

I sometimes serve as a mentor with the Unreasonable Group. Tom Chi, quite possibly one of the brightest people alive, is another mentor, and in the Unreasonable vernacular there is now a new verb: to Tom Chi an idea. What that means: come up with a mini pilot of your idea that costs less than $1,000 and will take less than a week. Give it a go. Make sure that the first contact isn’t going to cost you too much time or money. If $1,000 is more than you can afford, make it $100 or $10, but however you define it, you need to get your idea off the drawing board and into the real world, where it can either work or fail. If it works, take the next step. In the more likely event that it fails, examine the point of failure, refine the plan, and try again. Repeat until you succeed.

So by all means nurture your ideas through conversation. This envisioning process does indeed add value. And then, bearing in mind that you will probably never feel ready, just do it.

As Winston Churchill said, “success is the ability to go from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm”, and to be honest the enthusiasm is optional. Most of success is simply not giving up.

Other Stuff:

I’ve been getting requests to include more stuff about what I’m up to. So here we go.

January was meant to be a quiet month for thinking and strategising. That has sort of worked, although it certainly hasn’t felt all that quiet. Most days include between 3 and 6 one-hour calls and/or meetings with various people around the world. I’ve particularly been doing a lot of research into how we meet the energy needs of the future, while preserving the beauty and integrity of our ecosystems.

I’ve also been a guest on three podcasts – I’ll share details of those once they go online.

And some fun stuff too. The highlight of my year so far has been having lunch with Monty Python actor, author, and former president of the Royal Geographical Society Michael Palin. He is writing a book about the HMS Erebus, one of the two ships that Sir John Franklin took to the Northwest Passage in 1839, never to return, and wanted to ask me about waves. I wasn’t sure I could be any help, as the waves I’ve encountered have been warmer than those in the Arctic, and I experienced them from the deck of a 23-foot rowboat rather than a 100-foot sailing ship, but far be it from me to turn down the chance of lunch with MP, who was completely charming, and I was able to thank him for being a great inspiration to me when he was writing books like Full Circle about his BBC TV travel series.

On Tuesday I was at St James’s Palace, doing a presentation for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Scheme. Always a pleasure to meet the wonderful young people – and the Earl of Wessex – but the palace itself was absolutely freezing. I think the Queen needs to get some better insulation.

Next Monday I’m off to LA and then Mexico City for speaking engagements for Kaiser Permanente and the Young Presidents Organisation respectively. Also lining up some meetings in both places. While in LA I’m looking at getting a feature film made, loosely based on my life story, about the choices we make about how to live our lives. I’ll be staying with my good friends, Marcus Eriksen and Anna Cummins of the 5 Gyres Institute. While in Mexico City I’m hoping to meet at least part of the Noomap team, who are temporarily based in nearby Tepoztlan.

On my bookshelf at the moment, in various stages of being read, are:

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, by Yuval Noah Harari

Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis, by George Monbiot

Conscious Evolution: Awakening the Power of our Social Potential, by Barbara Marx Hubbard

And for some light relief, From Frazzled to Fabulous: How to Juggle a Successful Career, Fatherhood, ‘Me-Time’, and Looking Good, a hilarious mickey-take of patronising magazine articles telling women how they can have it all.

January 11, 2018

Crafting a Career in Conservation

A few weeks ago, I received an email from Ana, a biologist based in Chile, who was interested in moving into a career in conservation. She asked me if I could help her by answering some questions based on my own experiences.

I’m a real believer in standing on the shoulders of giants – most human endeavours have been done in some shape or form, or on some scale before, and I’ve often sought to learn from those who have gone before – so of course I was happy to help.

It occurred to me afterwards that my answers might be of interest to others, so here they are, lightly edited.

How would you describe your work?

Beach cleanup in Hawaii, 2008

Beach cleanup in Hawaii, 2008During the ocean rowing years, I was focused on raising awareness of our environmental challenges. I particularly focused on plastic pollution in the oceans, which is a very important issue, but I actually think climate change is the bigger challenge – but I was spending a lot of time in the US, and was finding it very difficult to have a sensible conversation there about climate change, because most people seemed to have already made up their minds one way or the other. Plastic pollution was a relatively unifying issue, and also a useful gateway, because it’s visible and tangible, and it’s easy for us all to reduce our plastic footprint immediately and with relatively little effort, by stopping the use of single-use plastic items like bottled water, plastic bags, straws, and coffee cups.

Looking ahead, I’m considering two possibilities; one specific, and one more meta. The specific one is [under embargo for now!]

The meta-project ties in with my view that our environmental challenges are like heads on a many-headed sea monster. We can keep cutting off heads, but it will keep on sprouting new ones unless we attack the heart of the monster – which is our misguided belief that we are somehow separate from nature, and have the right to exploit, pollute, and abuse it as we see fit. This narrative needs to change! And I’m trying to figure out how to bring diverse groups together to work on creating narratives to underpin a new reality.

Besides my environmental work, I also teach (a semester at Yale in 2017, workshops, short courses) and give motivational speeches. And write – two books published, possibly more to come, or I may focus more on blogs and articles.

What do you enjoy most about it? Least?

Enjoy most: I can’t think of anything more important for me to spend my time, talents, and energy on. I find it fulfilling and energising.

Least: it’s hard to find metrics that create any strong sense of progress. I have to maintain a belief in tipping points, and remind myself that I’m very unlikely to be the one to actually tip the balance, but I am helping add straws onto one side of the scales in the faith that one day they will tip in favour of sustainability.

Passion

What aspects of this work energize you the most? The least?

Walking to COP15 with kindred spirits: Big Ben to Brussels 2009

Walking to COP15 with kindred spirits: Big Ben to Brussels 2009Energise the most:

Meeting kindred spirits

Finding a way of articulating a problem or a solution in a way that resonates with people and inspires action

The least:

Occasionally getting daunted by the scale and intractability of the issues

Occasional disillusionment with human psychology, and its resistance to change

How many of the people in this field seem to be passionate about their work?

Lots of passion and energy, especially in NGOs, but in the past there has been a lack of coordination with other kindred organisations – but I see that improving a lot now.

Compensation

Is there a typical salary range for your career or does it all depend on sponsors and grants?

Personally, I have no regular salary. My main source of income is speaking fees.

What should I expect starting new in conservation for salary/compensation?

No idea!

Career Advancement

What experience or skills help you advance in your career?

Tenacity and determination

Research

Deep thinking

Connecting people

Self-care to avoid burnout

What do you think it take to be considered a leader in conservation?

Attempting to be articulate after 99 days at sea, Honolulu 2008

Attempting to be articulate after 99 days at sea, Honolulu 2008Clarity of vision

Articulate communication of ideas

Effective collaboration

Contribution to Society

How do people in your field measure or assess that impact?

With awareness raising, it is very difficult to measure, as there are so many variables, and effects are cumulative rather than easy to attribute to one organisation, person, or initiative. So at the moment I would say that the sense of contribution has to come from an intrinsic faith that I am doing my best, rather than from extrinsic impact measures – with occasional emails of appreciation that can really make my day!

Work/Life Balance

What are typical work hours for you?

Really hard to say, as there is no clear delineation between work and non-work. So I more or less work all the time or none of the time, depending on how you define “work”!

Working Style:

What is the most challenging aspects of your career?

I used to find the lack of a regular salary challenging, but now I’ve developed a fair degree of confidence that resources show up when needed.

Practical Considerations

Any practical advice you can give me as I look into changing my career?

Networking with Rep. Lois Capps at Ocean Champions

Networking with Rep. Lois Capps at Ocean ChampionsStay optimistic AND realistic.

Networks will be important, both as you seek a new position, and once you get there. Show up to as many events and conferences as feels comfortable, get business cards, connect on LinkedIn, build your address book. Webs of connection are how the world works.

IMPORTANT: get clear about your personal vision for what success looks like for you in this new arena. Use that vision to guide your decisions and keep you on track.

People

How would you describe the type of people who work in your field?

Some stellar minds. Some very passionate. Some a combination of both. Mostly guided by genuinely wanting to make the world a better place, but some egos too – as there are everywhere.

How would you describe the people you meet by working in your field?

Probably the same as above! But we all have something to bring to the party, regardless of individual talents etc. I hope I always treat everybody with respect.

What experience is needed to be successful at what you do?

For me personally, I definitely draw on the metaphorical value of my ocean rowing adventures – accumulation of many tiny actions, keeping an eye on the goal while doing what needs to be done in the day, etc.

But more generally, I think that energy, intellect, and clarity are more important than past experience. Likeability and willingness to genuinely collaborate – and give credit where credit is due – are good too!

If anybody is thinking about a career in conservation, or indeed in any other realm that is motivated by a desire to make the world a better place, I would say, please go for it! We may not do it for the financial rewards, but there are many things in life more important than money, and many riches that don’t have to be submitted to the taxman.

January 4, 2018

Narratives, Neuroscience, and No Money: Favourite Books of 2017

Forgive me, dear reader, for I have not blogged for eight months, since I finished teaching my courage class at Yale. But I have not been idle. There has been much going on behind the scenes, which I will gradually share with you.

To get started, I wanted to create a list of the books that most impacted my thinking in 2017, and share the ideas that I took away from them. This blog post ended up being considerably longer than intended, but if you’re interested in psychology, neuroscience, and the nature of reality, I trust you will find it interesting.

Deviate: The Science of Seeing Differently, by Beau Lotto

I had to miss Beau Lotto’s talk in London for the How To Academy (great speaker events) due to a diary clash, but I did get the book. He also has a TED Talk, but the book is better and deeper.

I had to miss Beau Lotto’s talk in London for the How To Academy (great speaker events) due to a diary clash, but I did get the book. He also has a TED Talk, but the book is better and deeper.

His main thesis is that the brain didn’t evolve to see accurately, but rather, usefully. It was the genes that were best able to assess threats and problems that survived. The genes for accuracy were less valuable than the genes for avoiding large mammals with big teeth.

So what does this mean? We can all tell what’s real and what’s not, right?

Wrong.

There are various reasons why our ability to perceive reality is limited:

We don’t sense all there is to sense. Other creatures have access to far more sensory information than we do. E.g. Birds can detect polarization of light. Stomatopods have 16 visual pigments compared with our 3. Bats can echolocate. Polar bears can smell a seal from 20 miles away, or 3 feet under the ice. Human senses are very poor and weak by comparison.

The information we take in is in constant flux. Everything changes and moves, so by the time we have processed the sensory information, it is already out of date.

All stimuli are highly ambiguous. Many perceptions are the end result of a multiplicity of factors, e.g. Visual perception is affected by clarity of air, perspective, etc. The eye is also often distracted by movement, at the expense of static objects.

There is no instruction manual. Perception evolved to guide us in how we react. But the perception doesn’t tell us how to react – we supply that part. The brain creates a meaning that generates the response.

And I would add 5. Our vision is affected by our scale. A tadpole will perceive things very differently than a blue whale, because what presents an existential risk to a tadpole (i.e. is big enough to eat it) does not present a risk to a whale (because there is nothing big enough to eat it – at least not in one gulp).

Following on with this them of reality not being as real as we think it is…

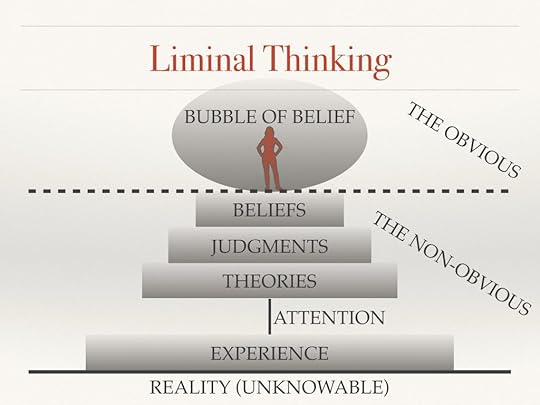

Liminal Thinking: Create the Change You Want by Changing the Way You Think, by Dave Gray

Follows on well from Deviate. Again, the idea is that our brain sits blindly in the black box of our skull, receiving information from our sensory peripherals – eyes, ears, nose, tongue, nerve endings – and doing its best to create a map that is useful in helping us navigate the world, and may incidentally also bear some resemblance to reality – but that is by no means essential.

Follows on well from Deviate. Again, the idea is that our brain sits blindly in the black box of our skull, receiving information from our sensory peripherals – eyes, ears, nose, tongue, nerve endings – and doing its best to create a map that is useful in helping us navigate the world, and may incidentally also bear some resemblance to reality – but that is by no means essential.

From the moment we’re born, our experiences start to shape our view of reality. For example, if we’re unfortunate enough to be badly parented, we may be hyper-alert for facial expressions indicating anger, to the extent that we perceive anger where there is none, because a false positive is more useful to us than failing to notice the danger signs when anger is looming.

Human attention is a rather poor and feeble thing – (according to Dr Bruce Lipton, in The Biology of Belief) our conscious mind can process 40 bits of information per second, compared with the stunning 20 million bits of information per second that our subconscious can handle. So we have to be very selective where we place our narrow beam of conscious attention. Naturally, it picks out the bits of information that have proved to be most useful to it in the past, based on our experiences.

Then, based on our experiences and hence our attention, we form theories, judgments and beliefs about the world around us, in order to efficiently assess and predict our “reality”. The brain uses a lot of energy, so it loves shortcuts, and the more preconceptions we have about reality, the less work the brain has to do. As William James said, “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices”. Or, as Anaïs Nin observed, “We see the world not as it is, but as we are.”

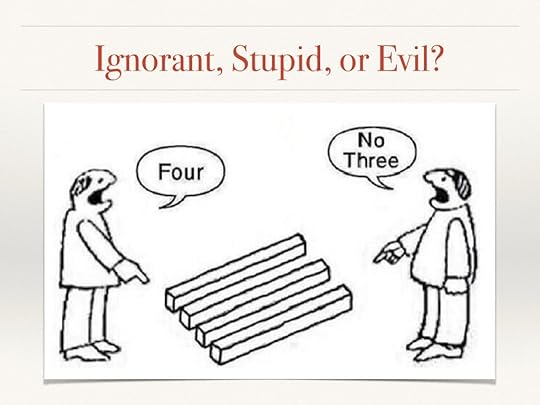

So, we sit atop this tottering edifice of assumptions and prejudices inside our bubble of belief, and think it is reality. So convinced are we that the contents of our bubble are real, that when we encounter someone who inhabits a different kind of a bubble, we think they must be ignorant, stupid, or evil, simply because they see the same “reality” a different way than we do.

And this bubble can be very difficult to penetrate. The problem is that there is a two-step process for accepting new information:

Is this new data consistent with what I already “know” about the world?

If this data does happen to be true, does the world make more sense?

Unfortunately we usually don’t get to Step 2 if the new data doesn’t pass Step 1. The brain loves coherence, preferring it to accuracy, so if the new data is not consistent with our existing mental models, it normally gets rejected outright – as any climate change campaigner who has argued with a climate change denier will know. All too often, the more fragile someone’s confidence in their existing worldview, the more staunchly they will defend it. An attack on their beliefs becomes an attack on their very identity.

(I’m sure we can all think of someone we know who seems to inhabit a very odd bubble of belief. But remember you are in one too, and yours seems as odd to them as theirs does to you.)

The best way to sneak under the radar here is to use not data and graphs, which give the brain advance warning that hostile data may be incoming, and will likely set the mental sirens blaring on red alert, but rather to use stories as a Trojan Horse for new information.

Bringing me nicely to….

Retellable: How Your Essential Stories Unlock Power and Purpose, by Jay Golden

(available as a free download here)

(available as a free download here)

Jay does a great job of showing how to tell great stories with a compelling arc that will have your audience eagerly hanging on your every word. Humans love stories, and being a superb raconteur is definitely a learnable skill. (If you have the knack, humour goes a long way too – compare this flight attendant’s safety briefing with the usual tedious gubbins, and decide which you’re more likely to pay attention to.)

(Jay happens to be the brother of Dane Golden, my old friend from the days of the Roz Rows the Pacific podcast with Leo Laporte. So I got in touch and we had a looooong conversation about the pleasures and power of narratives.)

So what would it look like if we created a compelling new narrative to fill…

The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough, by Alex Evans

I bought this book after hearing Alex Evans talking one morning on BBC Radio 4 about the need for new myths to replace the outdated religious and folk stories, if we are to create a better vision for the future. Amen to that, I thought, and I looked him up on the internet and emailed him to say how much I appreciated his ideas. I’ve since met Alex, who just happens to live close to my mum.

I bought this book after hearing Alex Evans talking one morning on BBC Radio 4 about the need for new myths to replace the outdated religious and folk stories, if we are to create a better vision for the future. Amen to that, I thought, and I looked him up on the internet and emailed him to say how much I appreciated his ideas. I’ve since met Alex, who just happens to live close to my mum.

His criteria for a good myth is that it unites rather than divides (wouldn’t that be nice?), and that it calls forth from people the kind of behaviours that contribute positively to society: purpose, health, prosperity, peace.

Specifically – and he is really talking my language here – a good myth should promote the concepts of:

a larger us (moving beyond the individualistic and even the national, to recognise that we are all humans, living together on a shared planet)

a longer now (see the ideas of the Long Now Foundation, founded by Danny Hillis, who I also met in 2017)

a different good life (where success is defined not what we consume, but by who we are)

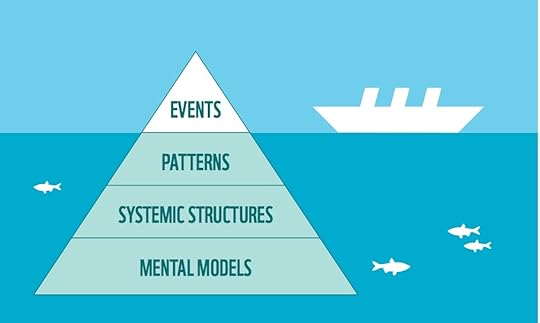

Ever since I read this report by the WWF and ZSL, with its diagram of a systems approach to change, I’ve been fascinated by the idea of underlying narratives/mental models, and how they need to change if we are to achieve genuine and all-pervading sustainability, rather than dealing with problems piecemeal. What got us through the last 10,000 years won’t get us through the next. We need a new story about what it means to be a human being in the 21st century.

A new narrative to underpin a major shift in consciousness – how hard can it be?!

It can be very hard, because these narratives form the absolute foundations of our modern society, according to…

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, by Yuval Noah Harari

According to Harari’s interpretation, the main reason that human beings have thrived as a species is that we are (as far as we know) uniquely capable of responding effectively and flexibly to a changing world. The main characteristic that enables this effective and flexible response is our ability to collectively create and believe in shared fictions, like money, countries, governments, legal systems, and corporations. None of these things have an objective existence outside of the human mind, but we believe in them as if they are real, and on these beliefs our entire modern enterprise is founded. Harari takes a hard look at many of these shared stories, and suggests the perils that lie ahead.

According to Harari’s interpretation, the main reason that human beings have thrived as a species is that we are (as far as we know) uniquely capable of responding effectively and flexibly to a changing world. The main characteristic that enables this effective and flexible response is our ability to collectively create and believe in shared fictions, like money, countries, governments, legal systems, and corporations. None of these things have an objective existence outside of the human mind, but we believe in them as if they are real, and on these beliefs our entire modern enterprise is founded. Harari takes a hard look at many of these shared stories, and suggests the perils that lie ahead.

The good news, in my view, is that if these fictions become no longer fit for purpose, we can change them, because we created them in the first place. The not so good news is that we seem to have forgotten that these are human-made fictions, and treat them as if they are objectively real.

It can take real courage to step outside of these collective fictions, like this guy did….

Moneyless Man: A Year of Freeconomic Living, by Mark Boyle

Moneyless Man: A Year of Freeconomic Living, by Mark Boyle

Mark Boyle decided to opt out of one of these shared fictions – the financial system – by spending a year living entirely without money. The practical challenges were considerable, but he also found great joy in the simplicity of his life, better health, and a sense of community with other people also seeking to live simpler lives with a lighter footprint. You could even say that, without the option to throw money at a problem, he was more connected to reality – the reality of where food, fuel and electricity come from, the reality of needing to share resources for survival, and the reality of true sources of happiness and wellbeing.

Which creates a nice segue to….

Happier People, Healthier Planet, by Teresa Belton

The author put an advert in The Big Issue (newspaper sold by homeless people to earn money) to invite responses from people who had made a conscious choice to live more frugally. Her research found that low impact living generally leads to impressively high levels of self-reported life satisfaction. This is a well researched and fascinating book that looks at low impact living from many social, economic, and psychological perspectives.

The author put an advert in The Big Issue (newspaper sold by homeless people to earn money) to invite responses from people who had made a conscious choice to live more frugally. Her research found that low impact living generally leads to impressively high levels of self-reported life satisfaction. This is a well researched and fascinating book that looks at low impact living from many social, economic, and psychological perspectives.

In keeping with my general theme of the year, the book also touches on the nature of reality. Psychologist Nick Baylis “identified three cognitive-behavioural processes in which most people partake to some degree; he terms these ‘quick fixes’, ‘reality evasion’ and ‘reality investing’. Quick fixes are strategies such as eating or drinking too much, gambling and retail therapy, while reality evasion involves denial of circumstances, escapism through excessive television watching or computer games playing, or hard drugs. Reality investment, by contrast, involves planning, practising of skills, pursuit of learning and the cultivation of good health. According to Baylis, reality investment is the defining characteristic of a positive relationship with reality; and reality investment is likely to enhance well-being. It is also, surely, the only form of relationship with reality that can further the cause of environmental sustainability. This is because studies have shown that happy people are not starry-eyed; those who have a positive outlook on life actually have a better grip on reality than the unhappy. They are better at attending to relevant information, including the negative and threatening, and are more realistic about what they can and cannot achieve. They have also been found to have greater self-control and self-regulatory abilities, and tend to be more co-operative, pro-social, charitable and ‘other-centred’. These are all qualities which are likely to incline individuals to consider the ethical dimensions of their consumption decisions.”

And speaking of happiness…

The Happiness Hack: How to Take Charge of Your Brain and Program More Happiness Into Your Life, by Ellen Petry Leanse

The Happiness Hack: How to Take Charge of Your Brain and Program More Happiness Into Your Life, by Ellen Petry Leanse

(Full disclosure: Ellen is a very good friend of mine. But personal bias aside, this is an excellent book!)

Integrating concepts from spirituality and neuroscience, Ellen gives us very practical ideas on how to be happy. So if you’d like to have more time to do things you love, create real connections to the world around you, stop living your life on autopilot, reclaims focus for the things that matter, and reduce stress – this is the book for you.

Health warning: as we now know that happier people are more closely in touch with reality, this book could cause you to escape your bubble of belief and start seeing the world as it really is.

Are you ready to take the red pill?

April 20, 2017

The Art of Living Courageously Week 12: WRAP-UP

This will be the last post in my blog series on The Art of Living Courageously. As we look at how to nurture courage in others and ourselves, we round up the main ideas from the class I’ve been teaching at Yale this semester.

Slideshow here. Podcast here. Syllabus here: GLBL252 Courage Syllabus.

I’m going to be taking a short break from the blog to wrap up the semester, mark papers, and have a mini-vacation. I’ll be back on May 18th.

Can courage be taught?

I’ve faced this question quite a number of times this semester, and I’ve changed my mind. At first I was a little defensive: “Well, of course it can be taught – else what am I doing here?!” But on reflection, I prefer to say that I don’t know whether courage can be taught, but I know it can be learned – because I’ve learned it, and I have no doubt that others can too.

The most important thing to know is that courage is not the absence of fear. That is fearlessness (which on occasions can look startlingly similar to stupidity). Courage is feeling the fear, and being able to do the thing anyway, because you are highly motivated to take action – and more on that later.

Even just taking a class on courage, and reading 150-200 pages a week about courage, and spending 2 hours a week discussing courage will, I believe, increase courage. The word is always on your mind. You start noticing and appreciating courage in others, and in yourself.

And where attention goes, energy flows.

Although it’s possible that courage can’t be taught, I’m sure it can be un-taught, or prevented from developing, and I’m thinking specifically of children. It is well documented that many western children now are allowed a lot less freedom than they used to be – freedom to roam, play, be in nature, get messy, walk to school, even get hurt or get bullied. Naturally, parents want to protect their children from harm (and social services will make sure that they do), but it may not be healthy to protect them from ALL harm.

You’ll be relieved to hear these were Photoshopped. No babies were harmed in the taking of these photos.

You’ll be relieved to hear these were Photoshopped. No babies were harmed in the taking of these photos.Children who grow up in an over-sanitised and over-sterilised physical environment don’t develop physical resilience to germs. Likewise, children who grow up in an over-protected environment don’t develop psychological resilience to knocks and setbacks. They don’t learn boundaries, what risks to take and which to avoid, or how to look after themselves.

And it’s tougher for girls. I was listening to an episode of Gayle Allen’s wonderful Curious Minds podcast (I can’t remember which one, but I recommend them all anyway) in which the interviewee described research conducted in a children’s playground. Around the climbing frame, parents were conspicuously more protective towards girls than boys, warning them against going too high or being too adventurous. What will that do to a growing girl’s courage, when she is consistently warned not to go outside her comfort zone?

How do we nurture our own courage?

I jotted down a list of techniques that I’ve used over the years to get myself past my fear, and when I took a step back, I realised that they all boiled down to:

This is seeing courage as a question of identity. Do you want to be the kind of person who lives courageously? Or not so much? There is no right or wrong answer. Courage is not compulsory. The point is to choose consciously who you want to be, and if you’re not happy with who you’re being, change!

Changing yourself is hard, but it’s not impossible. Trust me – I’ve done it.

We all have a self-concept, a story about who we are, and we tailor our behaviour to make that story be true. The story may be conscious or subconscious. You may only become aware of a subconscious story when you do something that is entirely against your own interests, and find yourself wondering – why did I just do that? The good news is that your subconscious story has just become conscious, so now you can do something about it.

Here are some ideas:

When your motivation is greater than your fear, you get courage.

So if you’re feeling too afraid to do what you want to do, pump up your motivation and/or find ways to decrease your fear.

TO INCREASE MOTIVATION

Motivation requires CONNECTION.

Connect with your values and your sense of purpose. Don’t know what they are? Do the Values Worksheet from Week 4 to figure out your values. As to purpose, take some time (and maybe your journal) and find that sweet spot in the intersection between what you love to do, and what will make the world a better place.

Motivation requires CARING.

Decide what you care about. What values would you go out of your way to uphold? What inspires your stewardship? What touches your heart?

Motivation requires AGENCY.

If you don’t believe you can affect the situation, you won’t feel like taking action. If you don’t believe you can affect the situation, why not? Do you really know that for sure? What are your assumptions? Are they really true? Have they ever not been true?

RETROSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE

Make your future self proud. You might be feeling afraid and powerless right now, in the moment, but how will you feel about yourself afterwards if you have felt the fear and done it anyway? And how will you feel if you don’t act?

CREATE A NEW YOU

Albert Camus said, “Life is the sum of your choices” – and it’s true. Every day, with everything you think, say, and do, you are declaring who you are – to the world and to yourself. You are constantly redefining your story about who you are. You are not the same person you were 10 years ago. And 10 years from now you will be a different person again. What kind of a person are you creating? And is that who you want to be creating?

KEEP PUSHING YOUR COMFORT ZONE

Denholm Elliott said, “Surprise yourself every day with your own courage”. You will end up a very different place over time if you keep challenging yourself to live more courageously.

USE CONFIDENT LANGUAGE

It’s easy to slip into a habit of using “hedging phrases” to diminish expectations, both our own expectations and those of the people around us. We say we will “try to” do something, rather than committing to making it happen. We diminish ourselves by saying “just” (see this seminal article by my dear friend Ellen Leanse). We take the edge off our voice of authority by saying “kind of” or “like”. We make our declarative sentences into questions by lilting our voice up at the end.

Especially as women, seeking to avoid being labelled “strident” or “bossy”, we undermine ourselves so as not to over-impress. This article in the Washington Post would be funny (and still is) if it wasn’t so close to the bone. e.g. “I came. I saw. I conquered.” would be said by a woman in a meeting as: “I don’t want to toot my own horn here at all but I definitely have been to those places and was just honored to be a part of it as our team did such a wonderful job of conquering them.”

The point is: speak confidently, and you will feel more confident.

OVERCOMING FEAR

There are tried and tested ways (i.e. tested by me, often in very trying circumstances) to diminish fear.

Positive self-talk

Remind yourself of a time when you acted courageously, especially remembering how you felt afterwards, and draw on those inner reserves again. Remind yourself what really matters to you, feel the importance, and allow that feeling to fuel you.

Evaluation of worst case scenario (decatastrophising)

It’s easy to let our imagination run away with us when we’re afraid. If you’ve seen the animated movie Inside Out, you can picture Fear freaking out at the slightest thing.

It’s easy to let our imagination run away with us when we’re afraid. If you’ve seen the animated movie Inside Out, you can picture Fear freaking out at the slightest thing.

It might sound contrary, but the best way to calm Fear down is to take a look at the worst that can happen, and figure out whether you can handle it. If you can’t, fair enough, but more often than not you’ll realise, when you look calmly straight at the thing that you’re afraid of, that it shrinks dramatically.

Have you heard about the cows and the buffalo? When cows see a storm coming, they try to outrun it. They can’t, and because they and the storm are moving in the same direction, they spend a lot longer than they need to under the rain and thunderclouds. Buffalo, on the other hand, run straight towards the storm, so very quickly they’re out the other side. You get the message.

SELF-SOOTHING TECHNIQUES

Breathing: always a good idea. When you’re afraid, it’s an even better idea. Close your eyes for a moment and breathe deeply, slowly, and mindfully. You will feel your shoulders drop, and your whole body relax. Adrenaline decreases, and oxygen to the brain increases, sharpening your mental faculties for whatever comes next.

Emotional detachment: Get over yourself. You’re very important to you, of course, but when you take a big step back, you are just one small person on a ball of dirt (and of course, water) whizzing through space. Everything passes.

Supportive belief system: “There is no such thing as an atheist in the Southern Ocean”, said Sir Robin Knox-Johnston (allegedly). If you have a faith, use it. It helps to believe/know that somebody has got your back.

Journaling: Not so useful in the burning-building kind of scary situation, but if time allows, sit down somewhere peaceful with a good notebook and a smooth-writing pen, and let the words flow. Write until you can’t write any more. See how much better you feel.

Share with a friend: with wine if necessary – but pick the friend even more carefully than the wine. The right kind of friend will let you talk. They won’t try to “fix” you, or the situation. They might offer a few well-phrased questions to help you work through the fear. Mostly they will give you love and support and the knowledge that you are not alone.

A Final Word on Fear

I’m sure you’ve heard this before, but FEAR has been described as False Evidence Appearing Real. The point is that fear exists only in your mind. Even the sweating palms and the rapid breathing and the tightness in your chest, which feel so real, are triggered by what is happening between your ears.

So because it exists only in your mind, you can choose whether to hold onto it, or drop it.

Breathe deep, reach deep, and draw up strength through the very soles of your feet.

You are capable of so much more than you would ever dare to believe. All it takes is a little courage.

Podcast

YouTube iTunes RSS (Android users can enter the link into their podcast client and subscribe directly)

See you on May 18th!

April 13, 2017

The Art of Living Courageously Week 11: Political Courage

Yet again, I marvel at how much my class is happening at the perfect time – ah well, maybe I should rephrase that. I don’t see any perfection in isolationist and bellicose policies, exactly when we should be coming together to address planetary problems and promote peace – but for sure, it is an interesting time to be talking about political courage.

I was pleased to find out that at least a couple of my students are fans of The West Wing, a far more inspiring and uplifting view of politics than the recent, more cynical, fictional representations of the political realm like House of Cards. (For a refreshing display of presidential integrity, accompanied by suitably rousing music and dewy-eyed loyalty, see “Let Bartlet be Bartlet”.)

This week we look at political courage from several different perspectives – citizen courage, the courage to go into politics, and courage in political leadership.

(NOTE: I have tried my best to remain politically neutral in this blog post, not because I am neutral, but because this is a class, and not an appropriate forum for my personal views. There will be times and places when I make my views clear, but not on this blog, this week.)

Citizen courage

This ties in with our studies of intellectual courage (week 3) and nonconformity (week 9), in that citizens have often felt moved to stand up courageously for what they believe in the face of an oppressive regime.

The case studies we examined were of dissidents and Nobel Peace Prize winners Carl von Ossietzky, Andrei Sakharov, and Adolfo Esquivel.

Carl von Ossietzky was a journalist who exposed the clandestine German re-armament, and as a consequence was sent to concentration camps, and died of tuberculosis while still in prison.

Alva Myrdal

Alva MyrdalAndrei Sakharov was a Soviet dissident and nuclear physicist, who turned activist after becoming concerned about the moral implications of his work on the hydrogen bomb. Increasingly outspoken against nuclear proliferation, he was sent to internal exile in the Soviet Union from 1980 until his release by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986.

Adolfo Esquivel is an Argentinian artist and pacifist who co-founded the Service, Peace and Justice Foundation and has stood up for human rights in Latin America despite repeated imprisonment and harassment from the authorities.

We also looked at the work of moral champions Norman Angell, Emily Greene Balch, and Alva Myrdal.

It seems that what all these individuals have in common is as follows:

Courage to go into politics

Politics can seem to many a uniquely unattractive career option. If you have a big ego and great ability, the money is much better in the City. If you don’t have a big ego, you don’t want to be around all those people who do.

Either way, you have to consistently strike an almost impossible balance between what you think is the right thing, what your party thinks is the right thing, and what your constituents think is the right thing. Get it wrong, and you end up compromised, demoted (or not promoted), or voted out.

The pages of history are littered with politicians who didn’t get it right – or, arguably they did get it right, but the public didn’t agree with them. A few examples:

Winston Churchill: legendary wartime prime minister, voted out of office at the end of the war as he wasn’t perceived as being the right person for the transition to peacetime.

Margaret Thatcher: after 11 years as prime minister, resigned after a leadership challenge from within her own party. (Love her or hate her, it’s hard not to admire her adherence to her beliefs.)

Zac Goldsmith: promised his Richmond constituents he would resign as Conservative MP if the third runway at nearby Heathrow got approval. It did, so he kept his promise, and stood again as an independent. His 30,000 majority was overturned and he lost the by-election.

And sometimes politicians face censure worse than being voted out of office:

Gabby Giffords: US Congresswoman shot in the head while meeting publicly with constituents. Survived, but left with serious brain injury.

Jo Cox: British MP shot and stabbed to death by a far-right fanatic during the height of Brexit in summer 2016.

Four US presidents shot and killed while in office -Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, and John F Kennedy – and we Brits haven’t been much more compassionate towards our leaders, having beheaded a few monarchs along the way.

So just remind me – why would anyone want to go into politics?

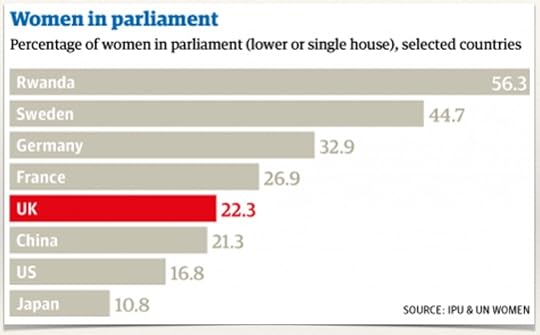

It seems that women are particularly reluctant, with the exception of just a few countries – probably a combination of family-unfriendly schedules, and a perception (not entirely inaccurate) that politics is still something of an old boys’ club. The media don’t help – research shows that female politicians are judged by a different standard than their male colleagues, even to the extent of a different vocabulary being applied. The impressive Angela Merkel of Germany remains an exception, rather than the rule.

(And a very good document here in the Media Women’s Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates and Politicians – although does contain some adult language.)

Quotas can help – whether or not you agree with them in principle, they do work to get the ball rolling.

And the good news is that since the election of Donald Trump, the US has seen a major uptick in women interested in running for office, supported by organisations like EMILY’s List and She Should Run. Blessings in heavy disguise and all that.

Courage in political leadership

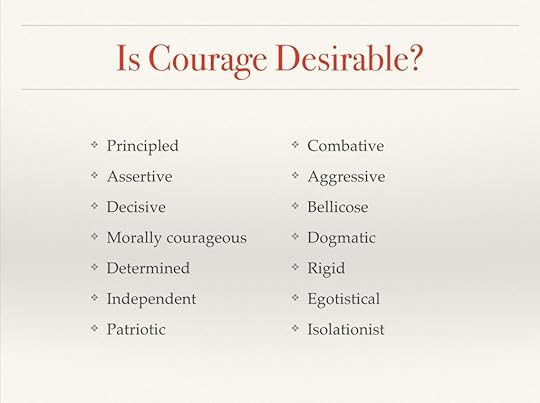

It could be debated whether we want to encourage courage in our political leaders. One politician’s courage can look like another person’s dogma.

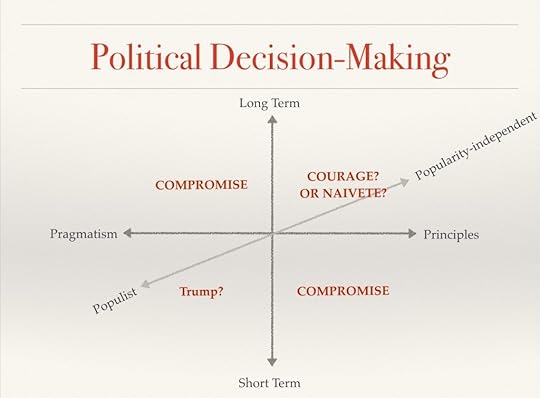

And to hark back to the fictional Jim Hacker in Yes Prime Minister, courage can lose you elections. It’s hard to change the world (or even your own country) when you’ve been booted out of office.

In fact, when you look at all the conflicting pressures on an elected politician, we might almost start to feel some sympathy for them. It seems that whichever way they turn, they are bound to lose the support of somebody – their constituents, their party, their peers, their donors, or maybe even their own family and friends.

Not only are they beholden to the relationships within which they operate, they are also creatures of their times. Being too far ahead or behind the wave of current opinion can make the difference between a glittering career and a tarnished one. And a politician who thrives in wartime may fall out of favour in peacetime (witness Winston Churchill), or simply pass their use-by date, as Margaret Thatcher found when she had vanquished the trade unions, and the single-mindedness that had got her thus far then became the cause of her downfall.

Of course, regardless of their competency or otherwise, they will get blamed for everything. Barack Obama said: “As president you’re held responsible for everything, but you don’t always have control of everything.”

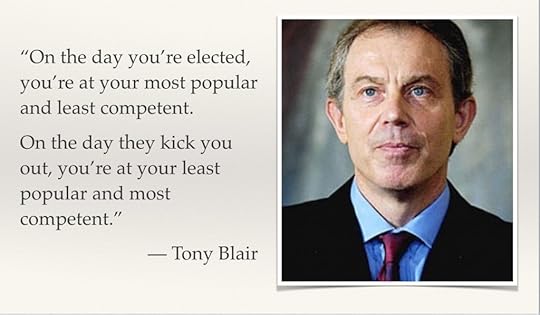

And finally, there is that great paradox of democratically elected political leaders: as Tony Blair said onstage when he visited Yale in 2012 when I was here as a World Fellow:

And yet YES, we DO want courage in our political leaders. Unrealistic and idealistic as it may be, we admire Jed Bartlet for taking a stand for principle over pragmatism. The very fact that we are so often disappointed by our politicians indicates that, despite everything, we still have high hopes for them. We want to look up to them as role models, as protectors, as pseudo-parents who will ensure our world is orderly, secure, and fair. Despite our carping, complaining, and political satire, politicians still dominate Gallup’s charts of most admired men and women.

Ultimately, if we don’t like the politicians we’ve got, it’s time to find our courage and decide that, if you want a job done properly, best do it yourself. Time to get out of the peanut gallery and into the political arena.

So much more to be said on this, but this blog post is more than long enough already, so I had better stop before it turns into a book. I do just want to say one final thing: politics is important, but it is not life and death (generally). Both the US and the UK endured divisive political campaigns in 2016, and a lot of bitterness continues. We all need to have the moral and intellectual courage to see beyond a person’s political beliefs to the person themselves, and get curious as to why they voted as they did. Only then, with empathy and understanding, can we heal the rifts.

Do let me know what you think – would you ever go into politics? If not, why not?

I just can’t resist finishing off with another classic moment from Yes Prime Minister.

Podcast

YouTube iTunes RSS (Android users can enter the link into their podcast client and subscribe directly)

April 6, 2017

The Art of Living Courageously Week 10: Military Courage

Even if you’re not in the military – heck, even if you’re a pacifist – there’s a lot we can learn from looking at courage in the military context. Having encountered quite a lot of military folks during my years in the adventure world, I will say that they are among the most organised, clear-thinking, calm, impressive – and courageous – people I have met.

Even if you’re not in the military – heck, even if you’re a pacifist – there’s a lot we can learn from looking at courage in the military context. Having encountered quite a lot of military folks during my years in the adventure world, I will say that they are among the most organised, clear-thinking, calm, impressive – and courageous – people I have met.

You could argue that it is the disciplined, tidy people who are most likely to be attracted to the military, rather than the military necessarily making them that way. Likely a bit of both. Either way, any organisation that can train its members to brave situations that are way beyond the imagination of us civilians (thank heavens) must have some interesting things to say about courage.

You can view the slideshow here, and the podcast is here. Syllabus here: GLBL252 Courage Syllabus

Warrior Courage

When I sat down to think about military courage, the first images that came to my mind were of the kind of courage that earns medals and accolades, such as in World War I – soldiers going over the top to face the enemy head-on, or enduring months at a time in miserable, wet trenches, surrounded by the decomposing body parts of their friends and colleagues.

Most soldiers were conscripted, rather than there by choice, and many were left permanently traumatised by what they had seen and done – but they endured none the less. (The threat of being shot for cowardice if they didn’t obey may have had some bearing on the matter.)

Medals are awarded to encourage the kind of courage that armies need if they are to function effectively. Nobody knows what was actually going through the minds of those poor buggers, whether they were being subjectively courageous, but for the greater good of the military unit and hence the defence of the realm, that was the kind of bravery that was required. The lure of medals probably didn’t figure specifically in their calculations, but we all operate in cultures in which certain behaviours are admired and rewarded, while other behaviours are discouraged and punished, and we adjust our actions accordingly.

Medals are awarded to encourage the kind of courage that armies need if they are to function effectively. Nobody knows what was actually going through the minds of those poor buggers, whether they were being subjectively courageous, but for the greater good of the military unit and hence the defence of the realm, that was the kind of bravery that was required. The lure of medals probably didn’t figure specifically in their calculations, but we all operate in cultures in which certain behaviours are admired and rewarded, while other behaviours are discouraged and punished, and we adjust our actions accordingly.

How does anybody cope with the brutal realities of war, and the very real physical danger? Rachman’s classic research in 1995 studied bomb disposal operators in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, working in Northern Ireland, and parachutists He was particularly interested in the role of training. He found that all the soldiers, regardless of their reported level of fear, were all able to carry out their duties quite competently after training.

In keeping with my general theory that we can act courageously when motivation > fear, he found that in the early stages of training people to carry out hazardous tasks, success is more likely if the person’s motivation is raised appropriately, and also that much of the training focused on decreasing subjective fear through raising competence.

In keeping with my general theory that we can act courageously when motivation > fear, he found that in the early stages of training people to carry out hazardous tasks, success is more likely if the person’s motivation is raised appropriately, and also that much of the training focused on decreasing subjective fear through raising competence.

You can probably relate to a situation where you were learning to do something that made you fearful in advance, but once you’d tried it once, you were elated at your own success and wanted to continue. If you haven’t experienced this feeling, please do – it is life-changing. But not with unexploded bombs… okay?! The point is that when we find the motivation to try something, and through continued trying we build our sense of competence, we are able to consistently perform scary actions with diminishing amounts of fear.

Military Leadership

War now is a very different matter than it used to be. In his TED Talk, General Stan McChrystal (one of my colleagues as a Senior Fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute) talks about his experience of 21st century warfare. In class, we watched and discussed the trailer from the movie The Eye in the Sky, in which the debate around a drone strike is conducted in government offices and military command rooms rather than in the heat of battle. Check out this interesting moral dilemma… and I’d be interested to hear your thoughts if you’d like to post a comment.

Hartley conducted research to find out what qualities military personnel most admired in their leaders – and the list is not so different from what we would hope to find in our managers, politicians, or even in parents:

Makes hard choices

Accepts responsibility

Does the right thing regardless of consequences to themselves

Displays honesty, integrity, and a personal code of ethics

Confronts risk without showing fear

Perseveres in face of difficulty

Leads from the front

Shows consistent courage in all aspects of life

We read an account (hagiography) of the legendary Field Marshall William J Slim who, despite the military context, seems to have been above all a superb people manager. Who wouldn’t want to work for a boss like this?

Power of vision of personal future: “Slim had become what he dreamt of becoming”

Ability to relate to people at all levels with respect and affection

Heart-based leadership, grounded in values

Proud sense of identity among his men as the “Forgotten Army”

Frequent praise for their accomplishments

Analytical approach to figuring out what his men needed in any given moment

Human Courage

The challenge can come when the courage of the human does not jibe well with how the military defines courage. What happens when a subordinate does not agree with the order from the superior? How do you balance military obedience against personal ethics?

This is how it works in the US military:

Military members disobey orders at their own risk – and could go to jail.

They also obey orders at their own risk.

An order to commit a crime is unlawful.

An order to perform a military duty, no matter how dangerous, is lawful, as long as it doesn’t involve the commission of a crime.

I asked a military friend of mine from the UK to offer her comments on courage. One of the stories she told was of a sergeant on deployment, a capable and disciplined man, who found the courage to reach out and admit he was suffering from PTSD and was becoming a danger to himself – and probably others. They were able to find him and help him. This is not the uber-disciplined, unflinching courage that we associate with the military, and certainly wouldn’t earn him any awards for gallantry, but courage comes in many guises.

On a personal level, I found the idea of Battlemind quite interesting.

I trust that not too many of you will ever find yourselves in a literal battle situation, but if we’re living a courageous life, there will inevitably be times of conflict when we need to step up our courage to a different level. There are concepts we can all take away from the Battlemind model, and be inspired by our brothers and sisters in arms to live a more courageous life.

And to adopt a core tenet of military training – the 7 Ps:

Perfect Planning and Preparation Prevents Piss-Poor Performance

– so it’s never too soon (or too late) to start preparing your courage!

Podcast (another P)

YouTube iTunes RSS (Android users can enter the link into their podcast client and subscribe directly)

Apologies again for the sound quality on last week’s podcast. All technical glitches now resolved, and we are crystal clear this week!

A reminder that the slideshow is here.

March 29, 2017

The Art of Living Courageously Week 9: Nonconformity

Nonconformity is widely idealised in our western societies. A quick scan of recently published books turns up such titles as Originals, The Art of Nonconformity, and Unfollow: Living Life on Your Own Terms. The classic Apple commercial of 1997 (The Crazy Ones) perfectly portrays our cultural perception of nonconformity as a heroic ideal: the lone genius, the world-changer, the rebel artist. (Also featured in the slideshow for this week’s class – see Slideshare.)

We also have a plethora of quotes about nonconformity – here are a few:

And we have come to demonise conformity:

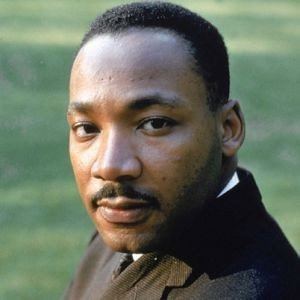

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King JrIn the military: “If everyone is thinking alike, then somebody isn’t thinking.”

— General George S. Patton

In social justice: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.”

— Martin Luther King Jr.

In the law: “It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right.”

— Henry David Thoreau

And yet the research shows that there are many benefits to conforming to society and to the status quo. It would be an exhausting and chaotic world indeed in which everything was being constantly questioned, and nobody was conforming to anything. So clearly nonconformity is not everywhere, always, and for everybody a good thing. In fact, nonconformists require conformists in order for their nonconformity to exist.

So “conformity” should not be seen as pejorative.

Many good points were made in class this morning, one of which was that the long, dark shadow of fascism may have made us unduly suspicious of conformity. We are still so horrified that something like the Holocaust could ever happen, when some kind of collective wilful blindness seems to have overtaken an entire armed force, that we use nonconformity as a kind of magic spell to guard against this ever happening again. Producer Vic and I also discussed this in the podcast, and having spent a great deal of time in Germany, he verifies that Germany celebrates nonconformity more than any other country he knows.

Another good point was that, even if we are nonconforming with regard to one thing, we are likely to be conforming to its opposite. It is now nothing out of the ordinary that Silicon Valley CEOs will wear t-shirts and sneakers rather than suits, and so their nonconformity has become the new normal.

Authentic Nonconformity

The danger here is that we end up aspiring to nonconformity as an end in itself. But there is a world of difference between someone who plays the part of a nonconformist in order to be perceived as cool or in some way superior, as if the rules don’t apply to them, and the authentic nonconformist who really isn’t thinking about how they are perceived but is simply living their life the way that feels right to them.

Paradoxically, the deliberate nonconformist (versus the authentic nonconformist) is self-consciously conforming to the commonly perceived package of nonconformity.

Paradoxically, the deliberate nonconformist (versus the authentic nonconformist) is self-consciously conforming to the commonly perceived package of nonconformity.

Hmm. Let me try that one again.

I may think it is befitting of my position, or in some other way advantageous, to project an aura of nonconformity. Research shows that people generally tend to assume that nonconforming people are more successful, and I may wish to exploit this tendency. So I deliberately construct an image that makes me appear nonconforming. But authentic nonconformity is not one of those things that can be faked. We intuitively know when someone is a genuine original, and when they’re just pretentious.

You might enjoy this spoof article from The Onion, about high schoolers experiencing peer pressure to be nonconformist, to the extent that conformists feel like the odd ones out.

Bell Curve from Conformity to Nonconformity

Of course, we’re all unique in our own ways. (I very much like this TED talk by Caroline McHugh, relevant to this.) But some of us want to stand out, others want to blend in, and the majority are somewhere in between.

We can picture this as a bell curve, and there will be separate bell curves for every realm of human endeavour – some may want to stand out for their fashion sense, but blend in when in the classroom.

We can picture this as a bell curve, and there will be separate bell curves for every realm of human endeavour – some may want to stand out for their fashion sense, but blend in when in the classroom.

Gilbert & George

Gilbert & GeorgeOthers, like Gilbert & George, may want to be utterly predictable in their everyday dress and lifestyle, in order to devote all their energy to creating extraordinary art.

And, as with most bell curves of human behaviour, those on the far extremes arouse deep suspicion, or even clinical diagnoses of mental disorders. The 2016 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders contains a new mental illness: Oppositional Defiant Disorder (with no hint of ironic awareness of its acronym), defined as “Ongoing pattern of disobedient, hostile, and defiant behaviour”. (Gandhi?)

The danger is that, as those on the extremes get labelled, and medicated to bring them safely back into the bulge of the bell curve, those who now find themselves as the new outliers will be regarded as the deviants, and so the bell curve narrows towards a bland average.

And maybe that is why we love and celebrate nonconformists, because the Apple advert does somewhat have that right – most of humanity’s greatest achievements have been initiated by the outliers, the weirdos, those who see the world in a different way (while noting also that history overlooks the outliers and weirdos who achieved nothing at all).

But is it Courage?

Back in Week 1, we defined courage as a wilful, intentional act, executed after mindful deliberation, involving objective substantial risk to the actor, motivated to bring about a noble or worthy purpose, despite the presence of fear. It qualifies on some counts, in that it involves risk – of social ostracism at the very least. Is it always wilful and intentional? If not at first, societies have a way of letting the nonconformist know when they have strayed, so if the nonconformist persists, it can be said that they are wilful and intentional.

Overall, we decided that nonconformity is indeed courageous – even now that inquisitions, witch-hunts, and holocausts are (mostly, but sadly not entirely) in the past.

Conclusion

If there are any conclusions to be drawn from this discussion, they might be:

The odd duck

The odd duckAuthentic nonconformity is not nonconformity for its own sake; it is the expression of deeply held, self-originated, and unusual beliefs about how life should be lived. It is the unique expression of one’s essence.

But we also need conformity, and a great deal of it, to enable and support nonconformity. Even nonconformists will be conforming in many areas of their lives. So we should be wary of judgements around conformity, or lack of it.

Being different can require courage, especially when relatively young. (The older we get, the less we generally care what people think of us, which is an enormous relief.) Finding that courage is important, not only to our own happiness and mental health, but also for the greater good, because those with a different way of seeing the world have the capacity to make it a better place for the rest of us.

Podcast:

As usual, Vic and I have a chat about the topic of the week in our podcast. Vic mentions this article about The New Tribalism and the Decline of the Nation State, which I recommend.

YouTube iTunes RSS (Android users can enter the link into their podcast client and subscribe directly)

A reminder that the slideshow is here.

And to end on a lighter note, that great philosopher, Monty Python, has this to say about nonconformity and individuality….

March 20, 2017

Go Hunt Life! Conversation with Todd Nevins

I recorded this podcast on 27th February with Todd Nevins of the Go Hunt Life podcast. Had a blast recording it – hope you enjoy it too.

If you are more of a prose person than a podcast person, Todd has kindly pulled out a selection of quotes from our conversation. Here are a few samples, and the full list is here.

“Life was passing, the future is unpredictable, and you have to crack on and get out there.”

“The fate of humans and the fate of the earth are interconnected. If we don’t look after out planet, it’s not going to work out for us humans.”

“Courage is about moral energy and making proactive decisions.”

That link again to the full list of quotes.

And we’re back to The Art of Living Courageously next week.

Other Stuff:

I’m back in Blighty for the mid-term break, spending time with nearest and dearest. Out of Trumpland and into Brexitland. Ah well, they say a change is as good as a rest!

March 16, 2017

Spring Break! And Wild Women in Hiding Summit

It’s the mid-term break at Yale, and I’m at home in the UK for a couple of weeks. But please read on, because I recently took part in an interview for Liz LaRocque’s Wild Women Summit, and I think you’ll enjoy this.

But just before we go there, if you’re looking for some courage resources, you might like to check out these posts from the archives:

The Courage to be your Greatest Self

Okay – now over to Liz and those Wild Women (equally applicable to men!) in hiding…

Liz writes:

Are you feeling stuck and bored with life?

Do you have a wild woman in you just waiting to be unleashed?

Do want to live a joyful, adventurous life?

Do you want to live out loud?

Do you want to feel confident?

Do you want to have the type of presence that commands attention as soon as you walk in a room?

Attend the free online telesummit, Wild Women in Hiding: Unleash Your Confidence Through Adventurous Challenges.

Click Here to go to the sign up page and you will have immediate access to free gifts and information on how to listen to the interviews.

When you attend this telesummit you will find inspiration, information, tips and strategies to unlocking your confidence, and unleashing the wild woman in you. You will learn how to break out of your shell and make your mark on the world, and how taking on adventurous challenges can help you do just that, all while finding a healthy dose of joy. You will also discover how to:

find your true grit and gumption,

push past self-imposed limitations,

connect with nature, and

seize life by the horns and really live life, not just exist.

This free online event starts on March 20, 2017 and runs for two weeks, with 2 interviews a day being released. You will have 48 hours of free access to the interview of each of our amazing, adventurous speakers. Get access by clicking on the following link: Wild Women in Hiding

Enjoy! I’ll be sending out another abbreviated blog post next week with news of a new podcast interview, then back to normal service on Thursday 30th March.

March 9, 2017

The Art of Living Courageously Week 8: Managerial Courage

We may not often think of courage in the context of work. Unless we’re a firefighter, or a soldier, or maybe a high school teacher in a tough inner city district, why would we need courage? Sure, we might be nervous about giving a presentation, or asking for a pay rise, or taking on a new role, but surely the penalty will only be that we embarrass ourselves, or screw up our next promotion. Or at the very, very worst we get fired, but nobody will die.

If risk is an essential component of courage, are work-related risks substantial enough for us to count this as courageous behaviour? Of course, losing a job can be catastrophic, especially if there is rent to pay and mouths to feed, but still, does courage in the workplace really count as courage?

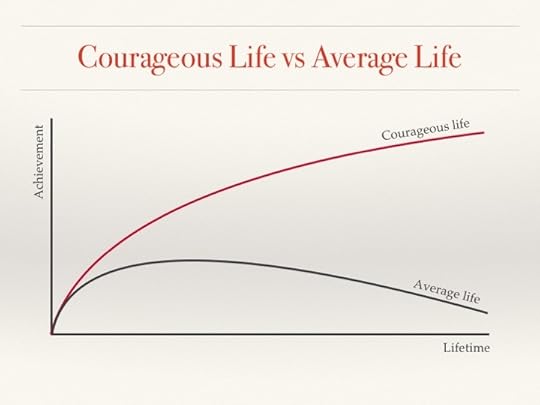

My answer would be that this course is about crafting a courageous life, on the premise that to live courageously creates a very different life trajectory from living averagely. And if we work, say, 34 hours a week for 48 weeks of the year for 40 years of our lives, that’s over 65,000 hours during which we can pursue our most courageous life… or not.

My answer would be that this course is about crafting a courageous life, on the premise that to live courageously creates a very different life trajectory from living averagely. And if we work, say, 34 hours a week for 48 weeks of the year for 40 years of our lives, that’s over 65,000 hours during which we can pursue our most courageous life… or not.

While the phrase “work/life balance” might imply that we park our “life” at the office door while we go to “work”, I’d like to suggest that work should be a part of our life, and our life a part of our work. Work has the capacity to present us with challenges and moral dilemmas that will test our courage in all kinds of ways, and it would be a tragedy to give up on those 65,000 hours as an opportunity to pursue our personal evolution.

Managerial Cowardice

We have probably all witnessed managerial cowardice – the boss who is nowhere to be found when the going gets tough, who is willing to throw his/her team under the bus rather than take responsibility, who won’t listen to opposing views, who doesn’t deal with the bad apple in the team, who can’t handle failure, who will adapt the truth to serve their own self-interest. Ringing any bells?

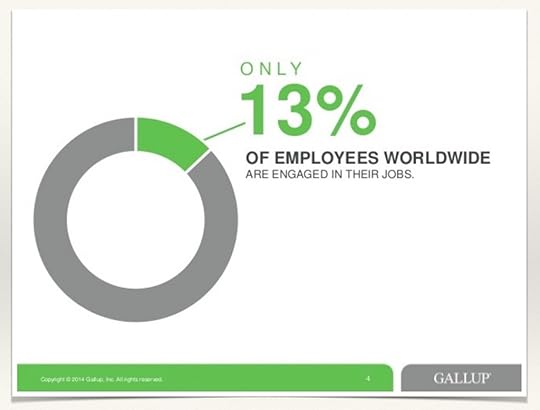

Let’s look at some statistics. According to this Gallup data, employees who work for engaged managers are 59% more likely to be engaged in what they do.

And overall, only 13% of employees worldwide are engaged in their jobs.

I can’t quite do the math, but that would seem to imply that there are a heck of a lot of disengaged managers, leading a lot of disengaged staff.

And a disengaged manager won’t be courageous, because on my assumption that:

When motivation > fear => courage

And assuming that engagement is necessary for motivation,

Then if you have no engagement, you have no motivation, and hence no courage.

(I can already sense outraged philosophers revving up to correct my fallacious logic, but to me this seems to make intuitive sense.)

And this all breaks my heart, because it adds up to an awful lot of human time, our most precious and irreplaceable resource, being wasted while we watch the clock and wait for our next pay cheque.

Managerial Courage

So how can we fix this? How can we get everybody to be switched on rather than tuned out?

Simon Sinek

Simon SinekGiven my current inclination for seeing everything through the lens of dominant narratives, my suggestion would be that for engagement to filter through the company like a beneficial contagion, what the company needs is a uniting and inspiring narrative about why they do what they do. (See Simon Sinek’s TED talk classic: Start With Why. Also Barry Schwartz on The Way We Think About Work Is Broken.)

When our working life is about so much more than selling our time so we can pay the bills, it takes on a whole different complexion. We care. We’re willing to go the extra mile. We’re willing to be courageous.

(And some other ideas to promote engagement and courage: encourage diversity of opinions; listen; give discretion; don’t over-proceduralise; lead by courageous example; reduce hierarchy; acknowledge workers as human beings; trust and be trustworthy; overcome status quo bias in favour of fresh ideas and the pursuit of excellence; tolerate failure.)

Workplace Courage – Reactive

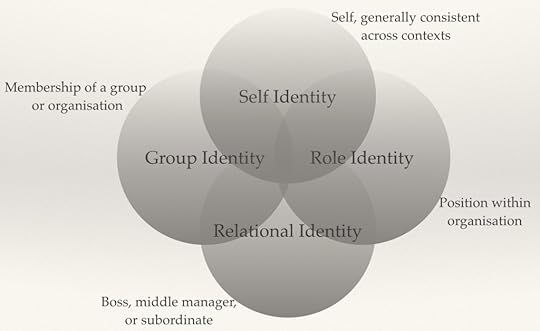

Courage at work often looks like a moral dilemma, and the moral dilemma often arises from a clash of identities. We bring a multiplicity of identities to bear on any decision, which can be simplified into four main ones:

When a question presents itself, tension can arise between these identities. For example:

A marine is part of a group that is sharing inappropriate photos of their female colleagues. Which wins: allegiance to the group or allegiance to the higher values of the Marine Corps? (true story)

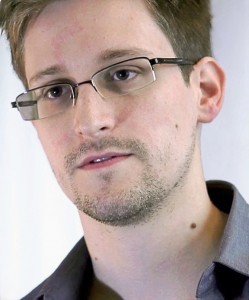

Edward Snowden

Edward SnowdenA worker is troubled by what he deems to be breaches of personal privacy in the name of national security. Which wins: his self-identity which values privacy, or his loyalty to his employer? (Edward Snowden)